Rectovaginal fistulas can be repaired through a multitude of approaches

including transanal, vaginal, perineal, abdominal, and transsacral. A transabdominal approach is usually reserved for high rectovaginal fistulas. The most

important aspect of rectovaginal fistula repair is closing the high-pressure

or rectal side of the defect. Fine, delayed absorbable suture should

be used in the closure of the rectal defect because of prolonged

tensile strength and the greater integrity of knots. Low/Midzone Fistulas Simple fistulotomy may be used in superficial anoperineal fistulas. Here, the tract extends

from an opening in the anal canal to the perineum, and usually, the

sphincter is not involved. The fistulous tract is laid open with a simple

incision. There are reports of women with Crohn’s disease

and anovaginal fistulas successfully treated by fistulotomy.19 More commonly, a transsphincteric approach with layered closure is used for low fistulas because of proximity to

the anal sphincter.28 An episioproctotomy is made and allows for excision of the entire fistulous

tract followed by a repair similar to that of a fresh fourth-degree

laceration at delivery. This technique requires meticulous reapproximation

of both the internal and the external anal sphincters. There

is a risk of fistula recurrence as well as anal incontinence if the healing

is compromised. This approach allows for reconstruction of the perineal

body as well. Episioproctotomy has been favorably described for

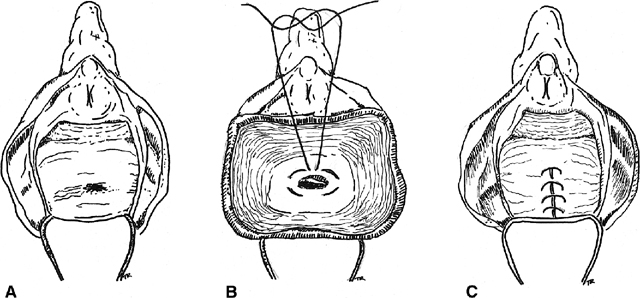

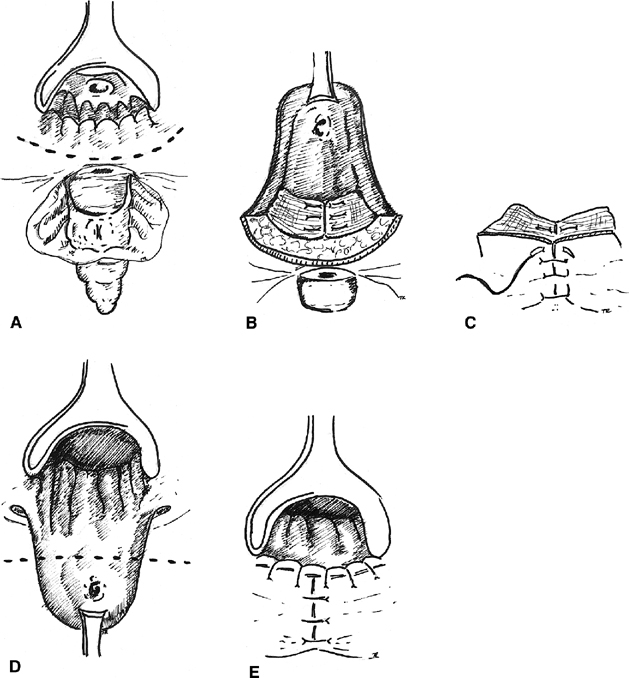

patients with quiescent Crohn’s disease without prior fecal diversion.29 Inversion of the fistula into the rectal lumen via a transvaginal approach is also suitable for

small low rectovaginal fistulas30(Fig. 3). The vaginal mucosa is incised around the fistula ostium, and the fistula

is closed with purse-string sutures tied in such a fashion as to

invert the soft tissue into the anorectum. The vaginal mucosa is then

reapproximated. For high rectovaginal fistulas, the anterior and posterior

vaginal walls, once mobilized, can be utilized in the inversion of

the fistula into the rectum (a modification of the Latzko procedure

for vesicovaginal fistulas).30  Fig. 3. Inversion technique of rectovaginal fistula repair. A. A low fistula is identified. B. The vaginal mucosa is incised around the defect. A purse-string suture

is placed. C. The purse-string is tied, inverting the defect into the anorectum, and

the vaginal mucosa is closed over the site Fig. 3. Inversion technique of rectovaginal fistula repair. A. A low fistula is identified. B. The vaginal mucosa is incised around the defect. A purse-string suture

is placed. C. The purse-string is tied, inverting the defect into the anorectum, and

the vaginal mucosa is closed over the site

|

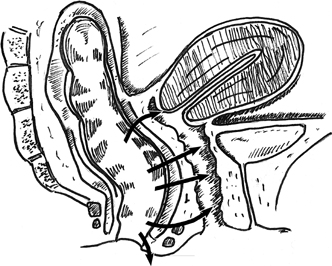

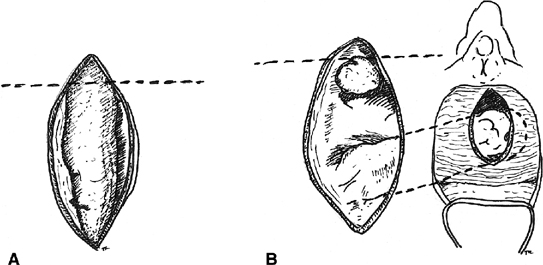

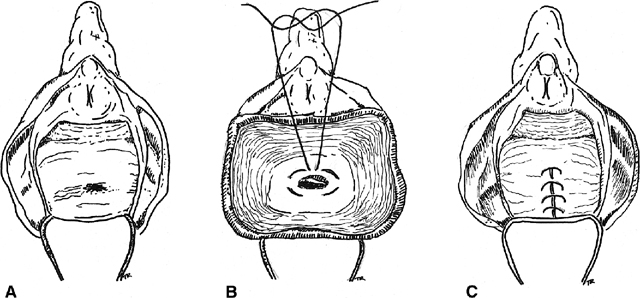

Boronow reported excellent results in patients with radiation-induced rectovaginal

fistulas, utilizing a layered closure with interposition of

a modified Martius graft of bulbocavernosis–labial fat pad tissue31 (Fig. 4). A vertical incision is utilized on the labia majora. The fatty tissue

is mobilized sharply with careful attention to preserving the blood

supply of the graft either inferiorly or superiorly. The thumb-sized graft

is tunneled subcutaneously beneath the vaginal mucosa and the labia

minora to overlay the repaired fistula site. The donor site may require

a drain. Boronow emphasized a delay of surgery for 6 months after

radiation exposure, a biopsy of the margins of the tract, a diverting

colostomy in advance of the repair, interposition of vascularized tissue, and

a tension-free closure. Elkins and colleagues have also utilized

the Martius technique to repair a number of rectovaginal fistulas

with satisfactory results.32  Fig. 4. Martius labial fat pad graft. A. The fibrofatty tissue is mobilized with preservation of either the superior

or the inferior blood supply. B. The graft is tunneled to the site of the repair. Fig. 4. Martius labial fat pad graft. A. The fibrofatty tissue is mobilized with preservation of either the superior

or the inferior blood supply. B. The graft is tunneled to the site of the repair.

|

Hoexter and coworkers, proposed a transanal repair.33 They excise the fistula tract, approximate the rectal musculature, and

advance the rectal mucosa caudad to protect the repair. The vagina mucosa

is left open to heal by secondary intention. The authors found no

recurrence in 35 patients with benign rectovaginal fistulas followed

for 1 to 6 years. Repair from the rectal side has the advantage of correction

of the defect from the high-pressure side, perhaps decreasing

the rate of failure of repair. Goligher has described a transperineal approach, through which the anus and rectum are separated from the vagina

and the fistula tract is divided.34 The mobilization of the vaginal and rectal walls permits a tension-free

closure. In addition, he recommends slight rotation of the rectum and

vagina in opposite directions to protect the suture lines. This approach

to repair allows the surgeon to preserve an intact internal and external

anal sphincter. Wiskind and Thompson devised another transperineal approach akin to Goligher’s.35 Using a transverse incision across the perineal body above the sphincter

complex, dissection is carried out between the anterior rectal wall

and the posterior vaginal wall. The external anal sphincter is preserved, vaginal

and rectal defects are closed separately, the fistula tract

is transected, and attention is directed toward reapproximation of

the endopelvic fascia in the midline and interposing the approximated

puborectalis muscle between the vaginal and the rectal defects. These

defects can be closed transversely or longitudinally. By closing the defects

longitudinally, vaginal and anal length is maintained. In the series

by Wiskind and Thompson, 21 patients with low fistulas, including 7 with

Crohn’s disease, had no recurrence during a follow-up

ranging from 3 months to 8 years (mean, 18 months). Sher and associates

also emphasize the importance of approximating the levator ani muscles

in the midline between the rectal and the vaginal suture lines.36 Laparoscopic upper rectovaginal mobilization facilitating the transvaginal

repair of recurrent rectovaginal fistulas has also been described

by Pelosi and Pelosi.37

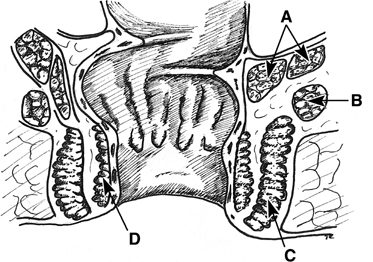

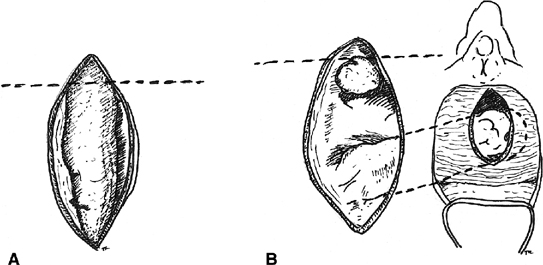

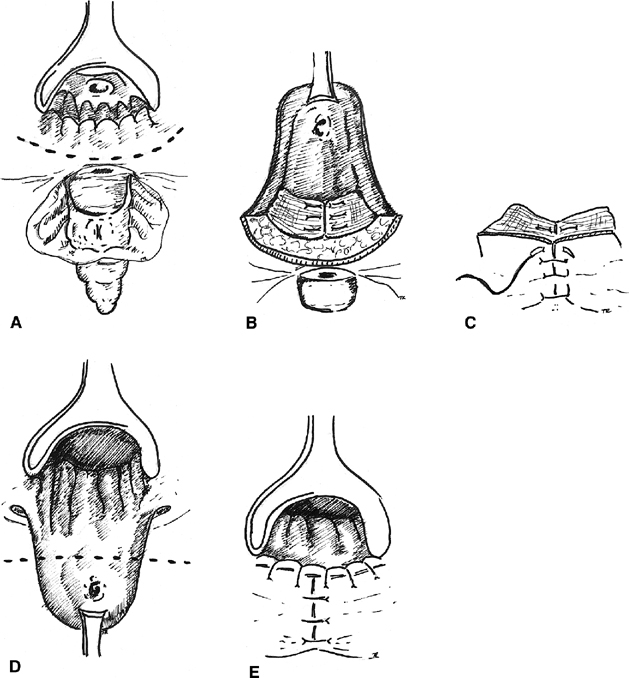

Many feel the best method of repairing low and midzone fistulas is the

sliding or advancement flap. Based on the work by Noble,38

there have been many modifications. Stowe and Goldberg describe developing

a broad-based flap of rectal mucosa, submucosa, and circular muscle and

advancing it caudad39 (Fig.

5). Before the flap is sutured over the fistula site, the tract is

excised from the distal end of the flap and the circular muscle is reapproximated

with absorbable suture. The flap is then advanced over the repair and

secured with interrupted absorbable sutures. The vaginal side is left

open to heal by secondary intention and provide drainage of the surgical

site. Several authors report a high rate of success with this method even

when used for the treatment of rectovaginal fistula secondary to Crohn’s

disease.36,40 Some have

described advancing the entire circumference (sleeve) of rectum for lesions

involving more than one third of the circumference of the anus.40,41

Fig. 5. Rectal advancement flap. A. A circumanal incision is made. B. The rectal flap is elevated, and the sphincter mechanism is repaired, C. The perineal tissue is closed. D. The flap is advanced with excision of the fistulous tract. E. The mucocutaneous junction is restored. Fig. 5. Rectal advancement flap. A. A circumanal incision is made. B. The rectal flap is elevated, and the sphincter mechanism is repaired, C. The perineal tissue is closed. D. The flap is advanced with excision of the fistulous tract. E. The mucocutaneous junction is restored.

|

High Fistula Repair Most often, a transabdominal approach is used for a colovaginal or high

rectovaginal fistula because of coexisting pelvic disease and the inaccessibility

of the fistula through the vagina. However, Lawson has successfully

used a perineal approach to treat fistulas near the cervix.42 The vagina is divided up to the lateral fornix, and the pouch of Douglas

may be opened behind the cervix to improve exposure. The rectum is

drawn downward for a layered repair. Lawson reported success with this

technique in 42 of 53 cases. The Latzko technique of using the anterior

and posterior walls of the vagina in the closure of a vesicovaginal

fistula can also be adapted for high rectovaginal fistulas.30 The etiology of the fistula must be appreciated when anticipating a transabdominal

repair for a high fistula. If the fistula is secondary to

trauma or pelvic drainage of an inflammatory process (e.g. diverticulitis), the

defect can be successfully closed by opening the rectovaginal

septum and closing the rectal and vaginal defects with interposition

of an omental J-flap. Bowel resection or the interposition of nondiseased

tissue is usually required in cases involving radiation injury or

advanced malignancy. Bricker and colleagues described a complex repair for radiation-induced

rectovaginal fistula.43 The procedure involves an onlay patch of well-vascularized intestine to

the damaged tissue and a descending colostomy. The advantages of Bricker’s

technique are that it requires only anterior mobilization

of the rectum, avoids denervation injury to the anorectum and hemorrhage, and

that the patch or flap retains its native blood supply. Timing of Repair The majority of fistulas secondary to trauma or obstetric causes may be

repaired early. Repair should be deferred until the resolution of active

infection, inflammation, induration, or local cellulitis. The authors

agree with Hibbard, who feels that the decision of when to operate

should depend on the condition of the tissue and not on an arbitrary

period of time.44 Diverting Colostomy Diverting colostomy is typically used in the management of radiation-induced

fistulas, very large rectovaginal fistulas, and some fistulas secondary

to inflammatory bowel disease. A repair of the fistula can then

be accomplished after all evidence of cellulitis and inflammation has

resolved (usually 8 to 12 weeks). Colostomy takedown may be scheduled

for 3 to 4 months after the repair. |