Multiple Gestation: biology and epidemiology

Authors

INTRODUCTION

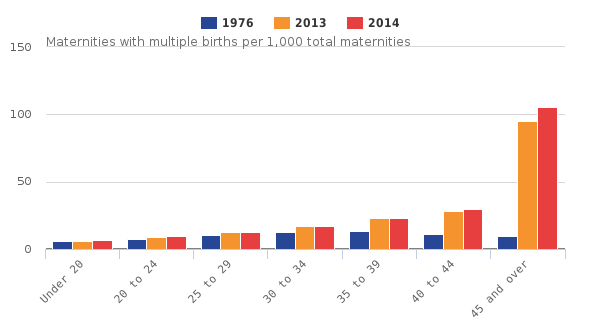

Multiple gestations are occurring more frequently as a result of increasing use of assisted reproductive technologies (ART), delaying pregnancy, increasing maternal age and immigration. In England and Wales in 2014, 1.60% of all maternities (including livebirths and stillbirths) were a multiple birth (see Figure 1).1 This equates to 10,839 women delivering twins, 148 women delivering triplets, and two women delivering quads or above, out of the 695,233 live babies which were delivered in England and Wales. There has thus been an increase in prevalence over time.1

Figure 1 Maternities with multiple births per 1000 total maternities in England and Wales in 2014 according to maternal age at conception1

Figure 1 Maternities with multiple births per 1000 total maternities in England and Wales in 2014 according to maternal age at conception1

The rate of all multiple births has risen compared to 1.56% in 2011, and 0.96% in 1976. This number will be an underestimate of the actual rate of multiple pregnancy conceptions owing to the high number of unrecognised first trimester miscarriages of multiple pregnancies, and so called “vanishing twin syndrome” whereby one twin/multiple miscarries in the first trimester and is reabsorbed, and the other twin/multiple(s) remains, usually with no further adverse effect. Historically this diagnosis was not made during pregnancy, but was made retrospectively postnatally. Vanishing twin syndrome does not refer to a single intrauterine death (sIUD) which occurs after 14 weeks' gestation, where the consequences of the sIUD may be more serious for the surviving co-twin/multiple(s)2, 3 (see chapters ‘Multiple Gestation: Antenatal Care’, ‘Multiple Gestation: Labor and Delivery’ and ‘Higher-Order Multiple Gestations’ for more details of the complications of multiple births). In addition to the gestational age at which fetal demise occurs, other important factors which affect the course of a multiple pregnancy are the chorionicity and amnionicity. It is these latter two factors which determine the pathway of antenatal care, as opposed to zygosity, therefore it is vital that they are correctly diagnosed ultrasonographically in the first trimester, normally before 14 weeks.4, 5

CHORIONICITY AND AMNIONICITY

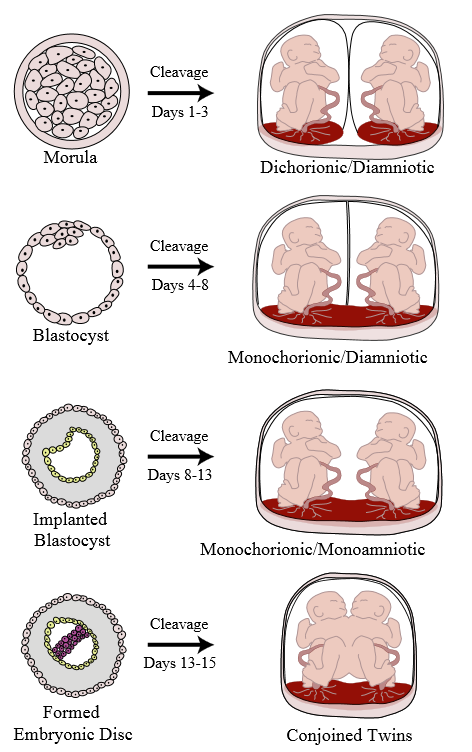

Figure 2 Chorionicity and amnionicity of twins (Retrieved from Dufendach, K. (Artist). (2008). Placentation. [Web]. Wikipedia https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3APlacentation.svg)

Figure 2 Chorionicity and amnionicity of twins (Retrieved from Dufendach, K. (Artist). (2008). Placentation. [Web]. Wikipedia https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3APlacentation.svg)

Dichorionic/diamniotic (DCDA/DiDi)

Each twin has its own placenta (although sometimes they grow adjacent to each other) and amniotic fluid sac so this type is considered the lowest risk multiple pregnancy. They are diagnosed by a lambda (λ) sign on first-trimester ultrasound. DCDA twins occur if cell division occurs before day 4.

Monochorionic/diamniotic (MCDA/MoDi)

Although the twins still have their own amniotic fluid sacs, this type of twins share a placenta which is considered higher risk as intertwin arteriovenous anastomoses may form resulting in potentially fatal complications such as twin–twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS) and twin-anemia polycythemia sequence (TAPS). They are diagnosed by a ‘T’ sign on first-trimester ultrasound where the two amnions meet. MCDA twins occur if cell division occurs between days 4 and 8.

Monochorionic/monoamniotic (MCMA/MoMo)

These twins share a placenta and an amniotic fluid sac, so they are considered the highest risk owing to not only the risks associated with monochorionicity as per MCDA twins, but also they are at high risk of cord entanglement. There is no dividing membrane seen on ultrasound. MCMA twins occur if cell division occurs between days 8 and 13.

Conjoined twins

These twins are fused together by various body parts and are very rare with an estimated prevalence of 1/45,000–200,000 births.6 Approximately 40% of conjoined twins will be stillborn, and 35% will die within the first 24 hours of life. Survival is heavily influenced by which body parts are fused. Conjoined twins occur if cell division occurs after day 12.

Higher-order multiples

These multiple pregnancies may have different combinations of chorionicities and amnionicities, and include singletons as well. If the couple is considering selective reduction, the chorionicity and amnionicity will play a role in determining which multiple to terminate. (See Higher-Order Multiple Gestations chapter for more information).

ZYGOSITY

Whether a pregnancy is DCDA, MCDA, MCMA or conjoined twins depends on (a) the timing of cell division as outlined above, and (b) the zygosity. Zygosity describes whether there is one zygote (monozygotic, MZ) or two zygotes (dizygotic, DZ). MZ twins make up approximately 30% of twin pregnancies and occur when one single embryonic mass divides. MZ twins result in 33% DCDA, 66% MCDA, 1% MCMA, although all MCDA twins and MCMA twins are MZ. DZ twins are created from more than one oocyte during the same menstrual cycle (i.e. two oocytes and two sperm) and therefore are always DCDA and non-identical. These ova may originate from the same follicle, or different follicles maturing in the same cycle, or less commonly from follicles from consecutive cycles (superfetation).7 The sperm may be from the same source, or rarely, from different sources (superfecundation). The majority of multiple pregnancies conceived using ART are DZ, although the rate of having an MZ pregnancy from an ART pregnancy is slightly higher compared to the natural MZ twin conception rate.8 The reason for MZ splitting is currently unexplained. MZ twins are particularly interesting for investigating genetic diseases as initially it was thought that MZ twins were genetically identical and thus any discordance between the twins was believed to be owing to environmental factors, whereas differences between DZ twins were thought to be either genetic or environmental.9 However, it is now accepted that genetic differences do exist between MZ twins.7, 10 As summarized by Weber and Sebire, these differences are thought to be a consequence of discordant segregation of genetic or cytoplasmic material, leading to two cell populations from the same original sperm and ovum, but with slightly different characteristics from post-zygotic mitotic crossing over, non-dysjunction, differences in imprinting or epigenetics, telomere size, X-inactivation or blastomere mass division. The rate of MZ twins remains constant, but the rate of DZ twins varies widely depending on a variety of factors listed below, including maternal age and parity.11

FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH MULTIPLE GESTATION

Various factors are thought to be associated with multiple gestations, some of which are more evidence-based than others. There does appear to be a link between the factors and a potential endocrine origin, which fits with the superovulation which occurs with DZ twins.

Assisted reproductive technologies (ART)

The majority of twins are conceived naturally, whereas higher-order gestations are mainly conceived through ART.1 It is estimated that approximately 20% of twins in the UK Millennium Cohort study were conceived using ART.12 However, the rate of UK in-vitro fertilization (IVF) pregnancies resulting in a multiple pregnancy has decreased dramatically from 27% in 2008 to 16% in 2014, owing to the introduction of single embryo transfer (SET) guidance if embryos are top-quality.8 However, increasingly UK couples are travelling abroad to have ART where SET is less encouraged, and consequently couples are returning to the UK with higher-order multiple gestations as more embryos are often transferred, and the numbers of higher-order multiple pregnancies are rising. This is despite the SET policy appearing to have no effect on cumulative pregnancy rates.13 One factor which affects the chance of having a multiple pregnancy is the type of ART, as described by Professor Keith in the ‘Higher-Order Multiple Gestations’ chapter.

Clomiphene citrate (Clomid)

Clomiphene is a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) prescribed to women with sub-fertility owing to anovulation or oligo-ovulation. It works by blocking estrogen receptors in the hypothalamus, thus inhibiting the negative feedback of estrogen, which increases the levels of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) and induces ovulation. Women who take clomiphene have a 10% chance of having a multiple pregnancy, compared to the UK background risk of 1.56%.

Maternal age

The average age of women at childbirth in industrialized countries has been increasing steadily for approximately 30 years.14 Between 1996 and 2006, births to women 35 years of age or older in the United Kingdom increased from 12% to 20% of all births.15 In 2006, a total of 5.6% of live births in the United Kingdom were to nulliparous women 35 years of age or older. Increased maternal age is associated with a higher incidence of multiple gestation births, as demonstrated by Figure 1. This is partly owing to the higher rate of ART in these women, but it is also thought to have a biological basis.11 The reason for this is unknown.

Parity

Parity is correlated with maternal age, but the effects have also been shown to be independent of each other with multiparous women exhibiting a higher rate of multiple pregnancies compared to nulliparous women.16 The reason for this is yet to be elucidated, although parity is unlikely to be a principal contributor to multiple gestations as the twinning rate has increased, whereas the average parity has decreased.12

Geography

The rates of multiple gestation pregnancies vary dramatically depending on country, although it is difficult to obtain recent accurate data for some countries, particularly lower income countries. The rates of multiple gestations have increased in other countries with Australia and the USA following a similar pattern to the UK. The countries with the lowest reported rates of twinning worldwide are Japan, Hong Kong and Singapore where rates have also increased, from 0.05% in 1972 to 0.09% of births being multiple gestations in 2001.17 The highest reported rates of twinning are in certain African countries, such as Nigeria and Zimbabwe which report rates as high as 6.65%.18

Family history

There does appear to be a genetic element to twinning with the trait being passed down both the maternal and the paternal side.11 Specific genes associated with DZ twins are beginning to be identified, and support that twinning is related to ovarian function.

Maternal BMI and height

A study by Basso et al. which used the Danish National Birth Registry reported a statistically significant association between women with a BMI ≥30 (OR 1.44, 95% CI 1.13–1.83) having a higher rate of naturally conceived twins, and women with a BMI <20 (OR 0.71, 95% CI 0.57–0.90) having a lower rate of naturally conceived twins even after correcting for maternal age and parity.19 They also found that taller women were more likely to have twins.

Other factors

There are other more dubious factors which research studies appear to both support and dispute as playing a role in the risk of having a multiple gestation as summarized by Hoekstra et al.11 These factors include maternal smoking, socioeconomic status, seasonal variation which affects the length of the day and food supply, use of the oral contraceptive, and folic acid. Nutritional status has also been postulated to be involved in multiple gestations as a change in diet in Yoruba, an area with a high incidence of multiple gestations with 1 in 11 people being a twin, was associated with a decrease in the twinning rate. Although, it is thought that the urbanization of Yoruba is more likely to have led to a decrease in the genetic isolation of people in Yoruba and affected cultural practices, as opposed to diet affecting multiple gestation incidence.12 Increased coital frequency has also been reported as increasing the risk of twinning, although this association is likewise uncertain.20

CONCLUSION

Multiple gestations are occurring more frequently as a result of increasing use of assisted reproductive technologies (ART), delaying pregnancy, increasing maternal age and immigration. Other factors associated with multiple gestations include parity, geography and family history. Chorionicity and amnionicity are vital as they determine the course of antenatal care owing to differences in associated risks. Zygosity explains the biological mechanism of the twinning with monozygotic twins developing from one embryonic mass, and dizygotic twins forming from more than one oocyte in the same menstrual cycle. Multiple gestations created by ART are more likely to be dizygotic, although with the introduction of the single embryo transfer guidance the rate of ART twins in the UK is decreasing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Fiona L. Mackie is funded by the Richard and Jack Wiseman Trust (charity number 1036690).

REFERENCES

ONS. Birth characteristics in England and Wales: 2014: Office for National Statisitcs; 2015 [Available from: http://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/livebirths/bulletins/birthcharacteristicsinenglandandwales/2015-10-08#background-notes. |

|

Hillman S, Morris R, Kilby M. Co-twin prognosis after single fetal death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(4):928-40. |

|

Mackie FL, Morris RK, Kilby MD. Fetal Brain Injury in Survivors of Twin Pregnancies Complicated by Demise of One Twin: A Review. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2016;19(Special Issue 03):262-7. |

|

NICE. Multiple Pregnancy. Excellence NIfHaC, editor. Manchester: NICE; 2011. |

|

Neilson J, Kilby M. Management of monochorionic twin pregnancy: Green-top guideline no. 51. RCOG, editor. London: RCOG; 2008. |

|

Denardin D, Telles J, Betat Rda S, Fell P, Cunha A, Targa L, et al. Imperfect twinning: a clinical and ethical dilemma. Rev Paul Pediatr. 2013;31(3):384-91. |

|

Weber M, Sebire NJ. Genetic and developmental pathology of twinning. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010;15:313-18. |

|

HFEA. Improving outcomes for fertility patients: multiple births 2015: HFEA; 2015 [Available from: http://www.hfea.gov.uk/docs/Multiple_Births_Report_2015.pdf. |

|

Hall JG. Twinning. Lancet. 2003;362(9385):735-43. |

|

Machin G. Non-identical monozygotic twins, intermediate twin types, zygosity testing, and the non-random nature of monozygotic twinning: A review. Am J Med Genet C: Semin Med Genet. 2009;151C(2):110-27. |

|

Hoekstra C, Zhao ZZ, Lambalk CB, Willemsen G, Martin NG, Boomsma DI, et al. Dizygotic twinning. Hum Reprod. 2008;14(1):37-47. |

|

Kurinczuk J. Epidemiology of multiple pregnancy: changing effects of assisted conception. In: Kilby M, Baker P, Critchley H, editors. Multiple pregnancy. London: RCOG press; 2006. |

|

Gremeau A, Brugnon F, Bouraoui Z, Pekrishvili R, Janny I, Pouly J. Outcome and feasbility of elective single embryo transfer (eSET) policy for the first and second IVF/ICSI attemps. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2012;160:45-50. |

|

Jacobsson B, Ladfors L, Milsom I. Advanced maternal age and adverse perinatal outcome. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(4):727-33. |

|

ONS. Report: Live births in England and Wales, 2006: area of residence. London: 2006. |

|

Bulmer M. The biology of twinning in man. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1970. |

|

Imaizumi Y. Demographic trends in Japan and Asia. In: I B, Keith L, Keith D, eds. Multiple Pregnancy. 2nd edn. London and New York: Taylor and Francis Group; 2005. p. 33-8. |

|

Nylander P. Ethnic differences in twinning rates in Nigeria. J Biosoc Sci. 1971;3:151-57. |

|

Basso O, Nohr E, Christensen K, Olsen J. Risk of twinning as a function of maternal height and body mass index. JAMA. 2004;291(13):1564-6. |

|

James W. Coital frequency and twinning. J Biosoc Sci. 1992;24:135-6. |