Preparation for Parenthood

Authors

INTRODUCTION

The process of preparing for parenthood consists of a series of steps, each of which presents unique challenges and dilemmas. This chapter explores the stages of preparation, beginning with the decision to become a parent, and progressing through choices regarding modes of birth, the impact of new parenthood, and child care issues. Finally, the problems that parenthood presents in several less common circumstances are discussed.

TRENDS AND THE EVOLUTION OF FAMILIES AND PARENTING

Preparing for parenthood begins with the decision to become pregnant, or the discovery of pregnancy in an unplanned circumstance. Fifty years ago, unreliable or unavailable contraceptive methods resulted in parenthood for couples regardless of readiness. In addition, couples suffering from infertility or repeated miscarriages had few options and generally accepted their inability to become pregnant, ultimately seeking other parenting options, such as adoption. In recent decades, the availability of effective and reliable contraception and sterilization techniques has given many the opportunity to chose the timing of parenthood. Advanced reproductive technologies now enable many couples with infertility problems to achieve a desired pregnancy.

For some couples, the decision to become pregnant is carefully weighed against the impact that pregnancy and birth will have on their careers, lifestyles, financial status, and marital relationship. Others consider the repercussions of pregnancy and parenthood only briefly, or not at all. Despite a recent decline in the rate of unintended pregnancy among adolescents, college graduates, and wealthy women, the number of unintended pregnancies increased among less educated, poor, and minority women.1

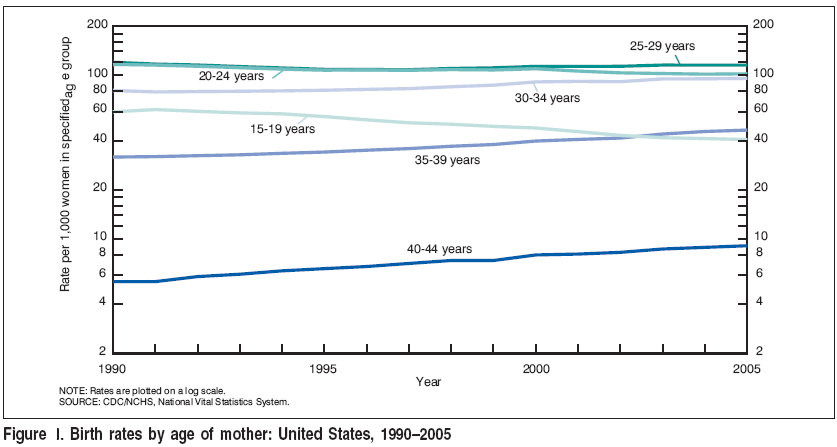

Statistical reports of birth and fertility rates reveal interesting childbearing trends. Historically the birth rate for teenagers increased at an annual rate of 5–7%, peaking in 1990. Since then, the birth rate for teenagers hasdeclined 34%, a trend attributed to consistent contraception use and delay in sexual activity.2, 3 However, in 2006 the birth rate in the United States for teenagers age 15–19 rose unexpectedly by 3%.4 Childbearing among women 30 years of age and older has also shown an increase (Fig. 1.). The pursuit of advanced education, careers and the necessity for two-income families has been largely responsible for the dramatic phenomenon of delayed childbearing. In addition, all measures of unmarried childbearing has risen 9–12% per year. Births to unmarried women constituted 37% of all US births in 2005. The recent increases in nonmarital birth rates have been especially notable among women age 25 and older.5

Nearly three-fourths of women aged 20 to 44—the age range when most women have small children—are in the workforce. According to the US Department of Labor, over 67% of employed women have children under the age of 18.6 Women who work, be it for personal fulfillment, economic necessity, or higher living standards, are often motivated to have fewer children. Family size has since decreased significantly, from an average size of 4.5 persons in 1915, to 2.61 in 2006.7, 8 In the past, this trend had been attributed to declining infant mortality and effective contraceptive methods. However, the current trend toward smaller families is attributable to postponement of childbirth and increasing preferences for no children or very small families.

The impact that this delay has had on the family has become increasingly evident in recent years. Several changes in the structure of the American family have emerged: an influx of children into alternative child-care settings, a change in the division of household duties, and an evolution in the roles of parenting for mother and father. Men have become much more involved in the decision-making process in all aspects of family evolution: pregnancy, childbirth and parenting, and child care. Unlike previous generations, prospective parents today are faced with many alternative theories and choices in parenting, beginning with the pregnancy itself.

CHILDBIRTH PREPARATION

The choices encountered by women and their partners for their childbirth experience have undergone remarkable changes throughout the twentieth century. One hundred years ago in the early 1900s midwives attended most of the births in the United States in the mother's home. As the training of physicians began to include obstetrics, use of anesthesia, and other advancing technologies, the place of delivery moved from the home to the hospital. In 1938 50% of births were in the home, most births were conducted by physicians rather than midwives. By 1955 only 1% of babies were born at home. That number has not changed in 2007. As medicine became more specialized, obstetricians attended increasing numbers of births, while general practice and midwife numbers declined. Certified nurse-midwives have been attending increasing numbers of births in recent decades to approximately 11% of US vaginal deliveries. This rise can be attributed to rising consumer preferences for birth alternatives and a falling number of obstetricians and family practice physicians attending births due to rising malpractice costs. Today's certified nurse-midwives are registered nurses with advanced obstetric and gynecologic training, typically at the master's degree level, who practice most commonly in a hospital setting in collaboration with a physician. Certified Professional Midwives (formerly known as "lay" midwives), who learn and attend births through apprenticeship and non university-based programs, generally deliver babies in the home. Licensure and regulation of CPMs varies state to state. Physicians trained in the specialty of family practice and maternal-child health are emerging as providers of maternity care, having the unique and valuable ability to provide intergenerational continuity of care for mothers, infants, and their families.

Because obstetric care has become more diverse and specialized, women can choose their type of care according to their particular needs and risks. Women can choose an obstetrician, family physician, or nurse-midwife for their prenatal care and delivery. Although they often overlap, the traditional and alternative or “noninterventive” models of health-care delivery emerge as a directive in this choice. The routine or traditional management of the birth process, including the use of technologies such as continuous fetal monitoring, epidural anesthesia, intravenous infusion, and episiotomy, are issues that a woman may consider when choosing her provider. A noninterventive approach that facilitates the natural processes of labor and birth with minimal use of routine interventions or analgesics is preferred by some women, while at the same time other women are choosing elective primary cesarean sections. The preparation for pregnancy and parenthood is becoming more consumer-oriented, and women are selecting their provider based on their personal philosophy and desires for their birth experience.

Less than 1% of US births occur at home; the majority of women in the United States choose to give birth in a hospital. Free-standing birth centers have recently become available in some locations as an alternative birth site, with 26% of out-of-hospital births occurring in free-standing birth centers.9 The safety of out-of-hospital births (free-standing birth centers or home birth) is an ongoing topic of dispute. Many issues surface, including claim to ultimate responsibility and control of the birth, safety, economics, and the right of a woman to choose her place of birth. Studies evaluating the relative safety of home, birth center, and hospital birth are difficult to analyze due to the difficulty in designing well-controlled, prospective, randomized trials. Existing studies report that the overall intrapartum and neonatal mortality rates in birth centers and planned home births are comparable to that of low-risk hospital births,10, 11, 12 asserting that they are a safe alternative to hospital birth. However the formal position of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends the hospital or free-standing birth center as the safest place to give birth.13

Childbearing women and their partners are almost universally encouraged to participate in childbirth education classes. Although some women choose not to take advantage of these classes, the benefits that can be derived from them warrant careful consideration. Community-based prenatal classes, Lamaze, Bradley, HypnoBirthing and other methods differ in their philosophy and techniques. Various other classes are also available, including ones that focus on breastfeeding, cesarean birth, prenatal exercise, newborn care, sibling preparation, child care, and more. The main emphasis of most childbirth preparation classes is upon the birth process per se, and unfortunately little attention is given to infant care skills or the impact a new baby will have on the marriage, careers, lifestyle, and financial state of the new parents. This aspect of preparation for parenthood is largely left to personal experience.

Closely associated with the choices of health-care provider, delivery locale, and childbirth education are the decisions involving the birth experience itself. In hospital birth settings, there is a choice of natural childbirth, narcotic analgesia, or epidural anesthesia for pain management. Some women will devise a “birth plan” to facilitate discussion of alternative positions for labor and birth, use of interventions such as amniotomy, intravenous fluids, episiotomy, and labor stimulation. Further preferences must be considered for the postpartum period: breast or bottle feeding, circumcision, return-to-work plans, child-care providers, and so on. The broad spectrum of choices available to childbearing women in the 21st century is far different from the traditional paradigm employed only a few decades ago.

THE TRANSITION TO PARENTHOOD

The heath-care provider is generally in close communication with a woman throughout her pregnancy and immediate postpartum period. Once the event of birth has occurred, however, new parents are left to rely on intuition, family advice, past experiences, child-care books, or telephone help lines. Few classes focus exclusively on teaching parenting strategies, skills, and expectations. Advice is proffered from family, friends, health-care professionals, and complete strangers. This advice is often conflicting and confusing. Parenting approaches used by previous generations are considered by some to be outmoded and even harmful, and the “authorities” may offer contradictory advice. The numerous parenting-education strategies employ differing philosophies about what works. Although there are educational books that describe the application of these strategies in detail, few couples prepare for this aspect of parenthood before the birth of their child, and few new parents have time afterward. There has been a century of child development research and advice dedicated to helping parents to parent their children. New parents soon become overwhelmed with the amount of information and opinion. Five media experts have written and spoken extensively: Benjamin Spock, T. Berry Brazelton, James Dobson, Penelope Leach and John Rosemond. Their advice is often contradictory and not always consistent with the scientific evidence. The vast amount of decades of research is daunting and therefore largely not accessible to the general public. Key controversial issues such as child care, working mothers, discipline, and electronic media stand out as concerns of new parents that must be addressed soon after the baby is born.14, 15, 16 Data suggests that parenting educational programs can make a significant contribution to the short-term psychosocial health of mothers. However, there is little evidence concerning whether these results are maintained over time, and there is limited follow-up information. More research is needed to determine effective parenting programs and the factors affecting successful outcomes.17

When a baby is born, important developmental changes occur in a family. The marital relationship of the parents is altered and the child becomes incorporated into the family. The relationship between marriage stability and parenthood has been largely studied. In 1957, LeMasters18 was among the first to report a decline in marital satisfaction after the birth of a child. Subsequent longitudinal studies have also suggested a decline in marital satisfaction associated with parenthood.19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24 The changes in marital satisfaction and period of adjustment caused by the birth of a child should be of great concern to health-care providers. Generally, it is the ongoing prenatal and postpartum relationship between the patient and the physician, midwife, and/or pediatrician that will reveal marital conflict or family dysfunction precipitated by pregnancy or childbirth. Social support services or family counseling may be necessary in cases of unresolved conflict or crisis in the young family.

PARENTING AND THE PROVISION OF CHILD CARE

The parent–child relationship is central to a child's moral development, social behavior, and ultimate attainment of adult independence. The fact that the mother and father are the most important people in the growing child's life prompts particular concern for the growing number of children in child care outside the family. The care of young children was once considered the responsibility of the family and extended family. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, grandparents played an instrumental role in religious training, education, and child care. However, the migration of families from rural to urban settings and economic changes characterized by an expanding white collar workforce resulted in a shift to functional support systems outside the family and a diminished role for grandparents. Data obtained from the 2000 US Census do not indicate whether there is a trend in grandparent involvement in parenting because it was the first time the question was asked, although recent data suggest an increase. In 2006, 8 % of households with children under 18 lived with at least one grandparent.25, 26

Most discussions about parenting and child care are intimately linked with the mother. Traditionally, the mother was considered the childrearer and the father the breadwinner. The women's movement, however, brought about a social change in the family roles of men and women, resulting in more shared childrearing. This change has not been without conflict, as women feel pressure both to stay at home to care for their children and to return to work. Employed mothers feel guilt and doubt about their child-care competence, whereas women who stay at home report a loss of social or professional standing. Women have become divided over employment status, choosing sides for what is viewed as best for the children. In response to this societal change, the demand for quality child care has become a major issue in government policy, the women's rights movement, and employee-benefit negotiations.27 The increasing number of dual-provider households has generated a flurry of research and books written designed to evaluate the expected negative impact of supplementary day care on a child's development. Research indicates, however, that substitute care has little effect on a child's emotional attachment, intellectual development, attention deficit disorder or social relationships. It appears that children who are enrolled in day care are similar developmentally to those reared by their parents at home.14, 16, 28 There is no easy solution: major attitudinal change by those who determine government and employee policy is needed in order to support the children of working mothers.

The involvement of fathers in parenting has changed dramatically in recent years. Part of this is due to an increase in the number of working mothers and changes in family demographics (such as divorce), necessitating a more active and shared role in parenting responsibilities by the father. The removal of obstacles to paternal participation in pregnancy and birth, and the impact of studies documenting the positive impact of the father's role on child well-being has also contributed to increased involvement. Fathers are attending childbirth classes, providing support during labor and birth, and learning basic infant-care skills to prepare for their new role. This is not without its drawbacks, however. Father participation has become expected rather than optional, an attitude nearly exclusive to the American middle class.29 Two problems arise:

- Fathers who choose not to participate are sometimes regarded with suspicion or malice by health-care providers.

- Participation may not be appropriate for all fathers.

More research is needed to determine the association between father participation and father–infant bonding, the marital relationship, and confidence in infant-care skills. However, important confounding variables such as perception, motivation, and expectations interfere with the interpretation of the information.22, 30, 31

Today's fathers are much more involved in the care and nurturing of their children. This new role has contributed to the stress of the transition to parenthood, as the father is viewed as financier, stabilizer, companion, and caretaker. Learning how to be an effective parent is a challenging task discovered mostly through trial and error. Health-care providers must acknowledge the pressure that is placed on today's fathers to perform efficiently in various roles. Further, this recognition must be coupled with understanding, compassion, and support for their transition into parenthood.

PARENTING IN UNIQUE CIRCUMSTANCES: SINGLE-PARENT FAMILIES

Single-parent families are becoming more commonplace. The birth rate for unmarried women aged 15–44 rose to 47.5 births per 1000, the highest rate in more than six decades.9 The proportion of non-marital births to teenagers continues to fall, while the birth rate for women ages 35–39 continues to increase, rising 52% since 1990. The factors responsible for this increase cannot be precisely determined, although it is known that a growing number of unmarried women of childbearing age are postponing marriage, and an increasing number of marriages are ending in divorce. It is estimated that one of every five families with children less than 18 years of age are headed by a single parent. Mothers continue to be the children's primary caretaker, with almost 75% of single-parent families maintained by the mother.32 These families are characterized by a high rate of poverty and minority representation, low educational levels, and high mobility. The economic and social needs of this group are enormous. Single-parent families can be divided into three types: (1) single parenting as a result of divorce or death; (2) unplanned single parenting; and (3) “elective” single parenting.

Divorce

America's divorce rate has declined from its peak in 1981 to its lowest level since 1970. Peaking at 5.3 divorces per 1,000 people in 1981, it began a slow decline to 3.6 in 2006. The reason for the decline is attributed to an increase in the number of couples who live together and a falling rate of marriage. The number of couples who live together without marrying has increased tenfold since 1960; the marriage rate has dropped by nearly 30% in past 25 years; and Americans are waiting about 5 years longer to marry than they did in 1970.

It is estimated that nearly half of all American children will experience the breakup of their parents' marriage before the age of 18 years, and nearly one-third of children will live in a single-parent home (Fig. 2).32, 33 For divorcing families, there has been little change in custody arrangements over the past 15 years, despite expert predictions to the contrary. The effect of divorce on parents and children will vary for different members of the family and generally involves an extended adjustment period. Many of the parenting responsibilities previously shared as a couple will fall upon the custodial parent. The stresses and difficulties in coping that are experienced by families in which the parents are divorced can lead to disturbances in personal and social adjustment of the child. This fact is countered, however, by the knowledge that divorce may be a positive solution to destructive family functioning. The long-term effects of divorce are still controversial although evidence suggests that children of divorced parents eventually were functioning as well as non-divorce homes.34, 35 Effective social support systems must be identified and developed that will help the family adjust to the parental changes associated with divorce.

Figure 2. Percentage of children ages 0–17 living in various family arrangements, 2004 Source: Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics. America’s Children: Key National Indicators of Well-Being, 2007. Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics, Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office. |

Unplanned Parenting

The number of unplanned pregnancies continues to escalate despite the availability of effective contraceptive methods. Reasons for this phenomenon have been proposed by various theories, including the intrapsychic conflict theory, which postulates unconscious desires to manifest fertility; and theories of complex contraceptive risk-taking behavior. Adolescent pregnancy is a matter of great public concern, as the rate which had been falling since 1991, showed an increase in 2006. Parenthood at an early age, not only affects the educational and social prospects for the adolescent mother, but also infants born to teenage mothers are at risk for poor birth outcomes such as low birthweight and preterm birth.9 Research results have found that adolescent parents have high levels of stress, inadequate social support, poor knowledge of child development, and inappropriate childrearing attitudes.36, 37, 38 Most teenage mothers live at home with a parent or parents, the majority keeping their babies. The ability of an adolescent to parent in a manner that promotes optimal child development is difficult to evaluate and longitudinal studies are minimal.36, 39, 40, 41

While most teen pregnancies can be established as unplanned, unplanned parenting among other age groups is more difficult to differentiate. The recent rise in unmarried and nonmarital childbearing does not necessarily indicate that the pregnancies were unplanned, as delayed childbearing and a simultaneous rise in cohabitation make such statistics meaningless.

Elective Single Parenting

Elective single parenting has become more acceptable and popular in the past decade. Women who choose to become a parent without the involvement of a partner typically come from two groups: those who have become discouraged with or jaded toward men in general; and those whose advancing age necessitates their becoming pregnant while they are still biologically able. For some this represents an ethical dilemma: personal attitudes regarding the upholding of a traditional family structure interfere with willingness to make modern reproductive options, such as artificial insemination, available to these women.42 There is some concern about the financial stability of elective single mothers and the lack of male role models for their children, believing that these factors may stunt the child's social and cognitive development.43 However, studies indicate that children raised by their mothers alone have no adverse effect on mothers' parenting ability or the psychological adjustment of the child.44 Many centers of reproductive medicine require a psychological profile to evaluate factors underlying the desire for elective single parenting.

GAY AND LESBIAN PARENTS

Changes in attitudes among lesbian women and gay men during the past few decades have allowed many to consider the possibility of parenthood. Although some consider adoption, there is an increasing number of lesbian women seeking artificial insemination and gay men seeking women to carry their child. Several concerns have been addressed. The biased view of lesbian women and gay men that focuses on their sexuality instead of their personal capabilities may falsely lead some to believe that homosexual persons cannot be good parents, or that their children will not have appropriate sexual role models. Research indicates, however, that the sexual orientation of the parent seems to have no effect on the child's sexual preferences. In addition, gay and lesbian parents have been shown to provide effective parenting for their children and the children are not measurably different in terms of gender identity, personality problems, or psychological development than children of heterosexual parents.45, 46, 47 Larger longitudinal studies of same sex parents, particularly gay men, are needed.

These new, nontraditional family forms are resisted by those concerned about the ongoing erosion of the family. Many institutions require psychological screening prior to acceptance into a donor insemination program. Gay men have greater obstacles in that they must find a woman willing to be inseminated and carry the pregnancy for them, or adopt. Legal custody issues arise. Although artificial insemination can minimize legal custody battles that must be fought by adoptive lesbian parents, the difficulty of finding a known donor or using a sperm bank presents a major problem.The legal, ethical, and health issues must be considered carefully by lesbian women and gay men who wish to become parents.48, 49 Health-care professionals must have an understanding of these issues and be attentive to their personal attitudes about this type of nontraditional parenting.

WOMEN WITH PHYSICAL CHALLENGES

There is a growing number of women with disabilities who are interested in pregnancy and becoming mothers. Technological advances in specialized adaptive equipment and an increase in social services offer greater opportunity for women with physical challenges to consider pregnancy, labor, birth and childrearing. Women with functional limitations are more likely to be overweight, smoke, have hypertension, and experience mental health problems which complicate pregnancy.50 There is very little research addressing the specific reproductive needs of women with disabilities. Evidence suggests that women with disabilities are more likely to deliver preterm and low birthweight infants and have more hospital admissions during pregnancy, cesarean deliveries, and readmissions within 3 months of delivery.51 Recent journal articles have helped to increase awareness of health care providers in the specific issues.52, 53, 54 Health-care professionals and the public must be educated to reduce the stereotypes of helplessness and passivity often associated with disabled women. Efforts have been made to provide public access, and technological advances have provided the opportunity for many women to function independently at work and at home. Women who are disabled must consider the same financial and emotional factors of parenthood as nondisabled women that will impact their lives. In order for parenthood to be a realistic option for these women, adjustments in living arrangements may be necessary, and a greater range of supportive services is often required. Thus, the financial cost of parenthood may be greater, the preparatory effort more involved, and the physical requirements more challenging among these women than among women without disabilities.55

FUTURE TRENDS

Many societal changes have had an impact on parenthood in the United States. Women are postponing childbearing and having fewer children. Subsequently, an increasing proportion of couples will have impaired fertility as a result of advancing age. Conditions affecting a woman's ability to conceive and bear children may be more difficult to treat as she becomes older.

More mothers than ever are in the workforce, and consequently more children are in alternative child-care settings. This is not likely to change, as two incomes are becoming increasingly necessary to meet household costs of living. The impact of increasing numbers of working mothers is far-reaching. Alternative child-care settings will increase in number, thus increasing the concern over their quality, size, and accessibility. Government representatives and employers must recognize the need for major changes in policy to assist working mothers and their children. There is a wide spectrum of choices available to women preparing for childbirth: birth attendant, birth setting, childbirth education classes, and various procedures and medications proffered during the birth itself. The trend for consumer involvement and control is likely to continue as women become more knowledgeable about their own health care. To meet the needs of childbearing women, prudent health-care providers and hospitals will keep abreast of consumer requests for birthing alternatives.

Single-parent families are more commonplace today because of high divorce rates, unplanned parenting, and elective single parenting. Nontraditional parenting arrangements chosen by single professional women and homosexual couples are occurring more frequently, challenging societal norms and changing definitions of parenthood and family.

REFERENCES

Finer LB, Henshaw SK: Disparities in rates of unintended pregnancy in the United States, 1994 and 2001. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2006; 38(2): 90-6 |

|

Guttmacher Institute: US Teenage Pregnancy Statistics: National and State Trends and Trends by Race and Ethnicity. |

|

Santelli JS, Lindberg LD, Finer LB et al: Explaining recent declines in adolescent pregnancy in the United States: thecontribution of abstinence and improved contraceptive use. Am J Public Health 2007;97(1): 150-6. Epub 2006 Nov 30 |

|

Ventura S: Statcast: "Teen, Unmarried Births on the Rise" US Department of Health and Human Services, Center for Disease Control, National Center for Health Statistics, December 5, 2007 |

|

Martin JA, Hamilton BE et al: US Department of Health and Human Services, Center for Disease Control. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2007; 56(6) |

|

US Department of Labor: 2006 Annual Social and Economic Supplement, Current Population Survey, Bureau of Labor Statistics. http://www.bls.gov/cps/wlf-table6-2007.pdf |

|

US Bureau of the Census: Historical Statistics of the United States, Colonial Times to 1970, Bicentennial edn. Millwood, NY: Kraus, 1989 |

|

US Census Bureau: Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2006, Families and Living Arrangements. http://www.census.gov/population/www/socdemo/hh-fam.html |

|

Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD et al: Births: final data for 2005. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2007; 56(6): 1-103 |

|

Rooks JP, Weatherby NL, Ernst EK et al: Outcomes of care in birth centers: The National Birth Center Study. N Engl J Med 1989; 321(26): 1804-11 |

|

Anderson RE, Murphy PA: Outcomes of 11,788 planned home births attended by certified nurse-midwives: A retrospective descriptive study. J Nurse Midwifery 1995; 40: 483 |

|

Olsen O, Jewell MD: Home versus hospital birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000; (2): CD000352. |

|

American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology and the American Academy of Pediatrics: Guidelines for Perinatal Care, 6th edn, 2007 |

|

Rankin JL: Parenting Experts: Their Advice the Research and Getting it Right. Westport Connecticut: Praeger Publishers, 2005 |

|

Hulbert A: Raising America: Experts, Parents, and a Century of Advice about Children. New York: Alfred A Knopf, 2003 |

|

Sclafani JD: The Educated Parent: Recent Trends in Raising Children. Westport Connecticut: Praeger Publisher, 2004 |

|

Barlow J, Coren E: Parent-training programmes for improving maternal psychosocial health. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004; (1): CD002020 |

|

LeMasters EE: Parenthood as a crisis. Marriage Fam Liv 1957; 19: 352 |

|

Elek SA, Hudson DB, Bouffard C: Marital and parenting satisfaction and infant care self-efficacy during the transition to parenthood: the effect of infant sex. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs 2003; 26: 45 |

|

Schulz MS, Cowan CP, Cowan PA: Preventive intervention to preserve marital quality during the transition to parenthood. J Consult Clin Psychol 2006; 74: 20 |

|

Lawrence E, Rothman AD, Cobb RJ, et al: Marital satisfaction across the transition to parenthood. J Fam Psychol. 2008; 22(1): 41 |

|

Shapiro AF, Gottman JM, Carrere S: The baby and the marriage: identifying factors that buffer against decline inmarital satisfaction after the first baby arrives. J Fam Psychol 2000;14(1): 59-70 |

|

Perren S, von Wyl A, Burgin D et al: Intergenerational transmission of marital quality across the transition toparenthood. Fam Process 2005;44(4): 441-59 |

|

Schulz MS, Cowan CP, Cowan PA: Promoting healthy beginnings: a randomized controlled trial of a preventiveintervention to preserve marital quality during the transition to parenthood. J Consult Clin Psychol 2006;74(1): 20-31 |

|

Simmons T, Dye JL: Grandparents living with grandchildren: 2000. Census 2000 Brief. October 2003 http://www.census.gov/prod/2003pubs/c2kbr-31.pdf |

|

Family and Living Arrangements, US Census Bureau News, Public Information Office. Washington DC: US Department of Commerce, May 25, 2006 |

|

Sylvester K: Caring for our youngest: public attitudes in the United States. Future Child 2001; 11(1): 52-61 |

|

Anon: Are child developmental outcomes related to before- and after-school carearrangements? Results from the NICHD study of early child care. Child Dev 2004; 75(1): 280-95 |

|

May KA: Father participation in birth: fact and fiction. J Calif Perinat Assoc 1982; 2: 41 |

|

Paris R, Helson R: Early mothering experience and personality change. J Fam Psychol 2002;16(2): 172-85 |

|

Bretherton I, Lambert JD, Golby B: Involved fathers of preschool children as seen by themselves and their wives:accounts of attachment, socialization, and companionship. Attach Hum Dev 2005; 7(3): 229-51 |

|

US Census Bureau: Statistical abstract of the United States: ‘‘Families and Living Arrangements’’; 2008 |

|

Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics: America’s Children: Key National Indicators of Well-Being, 2007. Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics, Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office |

|

Sclafani JD: The Educated Parent: Recent Trends in Raising Children. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger Publishers, 2004 |

|

Heatherington EM, Kelly J: For Better or for Worse: Divorce Reconsidered. New York: Norton, 2001 |

|

Hanna B: Negotiating motherhood: the struggles of teenage mothers. J Adv Nurs 2001; 34(4): 456-64 |

|

Wahn EH, Nissen E, Ahlberg BM: Becoming and being a teenage mother: how teenage girls in South Western Swedenview their situation. Health Care Women Int. 2005;26(7): 591-603 |

|

Holub CK, Kershaw TS, Ethier KA et al: Prenatal and parenting stress on adolescent maternal adjustment: identifying a Matern Child Health J 2007;11(2): 153-9. Epub 2006 Oct 25 |

|

Koniak-Griffin D, Anderson NL, Verzemnieks I et al: A public health nursing early intervention program for adolescent mothers:outcomes from pregnancy through 6 weeks postpartum. Nurs Res 2000;49(3): 130-8 |

|

SmithBattle L: Learning the baby: an interpretive study of teen mothers. J Pediatr Nurs 2007; 22(4): 261-71 |

|

Stiles AS: Parenting needs, goals, & strategies of adolescent mothers. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs 2005; 30(5): 327-33 |

|

Strong C: Harming by conceiving: a review of misconceptions and a new analysis. J Med Philos 2005; 30(5): 491-516 |

|

Amato PR: The impact of family formation change on the cognitive, social, and emotional Future Child 2005;15(2): 75-96 |

|

Murray C, Golombok S: Solo mothers and their donor insemination infants: follow-up at age 2 years. Hum Reprod 2005;20(6): 1655-60. Epub 2005 Feb 25 |

|

Greenfeld DA: Reproduction in same sex couples: quality of parenting and child development. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2005; 17(3): 309-12 |

|

Tasker F: Lesbian mothers, gay fathers, and their children: a review. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2005;26(3): 224-40 |

|

Rivers I, Poteat VP, Noret N: Victimization, social support, and psychosocial functioning among children of Dev Psychol 2008; 44(1): 127-34 |

|

Baetens P, Camus M, Devroey P: Counselling lesbian couples: requests for donor insemination on social grounds. Reprod Biomed Online 2003; 6(1): 75-83 |

|

Lev AI. The Complete Lesbian and Gay Parenting Guide. New York: Berkeley Books, 2004 |

|

Chevarley FM, Thierry JM, Gill CJ et al: Health, preventive health care, and health care access among women with disability. Womens Health Issues 2006; 16(6): 297-312 |

|

Gavin NI, Benedict MB, Adams EK: Health service use and outcomes among disabled Medicaid pregnant women. Womens Health Issues 2006; 16(6): 313-22 |

|

Smeltzer SC: Pregnancy in women with physical disabilities. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2007; 36(1): 88-96 |

|

Lorenzi AR, Ford HL: Multiple sclerosis and pregnancy. Postgrad Med J 2002; 78(922): 460-4 |

|

Smeltzer SC, Sharts-Hopko NC, Ott BB et al: Perspectives of women with disabilities on reaching those who are hard to reach. J Neurosci Nurs 2007; 39(3): 163-71 |

|

Rogers J. The Disabled Woman's Guide to Pregnancy and Birth. New York: Demos Medical Publishing, 2006 |