Many different scoring systems exist for discriminating benign from malignant adnexal masses. These scoring systems evaluate masses for solid elements, cyst wall thickness, number, thickness, and irregularity of septations, and the presence of ascitic fluid. Numerical scores are applied and masses that score higher than a certain cutoff are considered potentially malignant.5–7 As recently discussed by Jermy and colleagues, the application of these numerical systems is complex.8

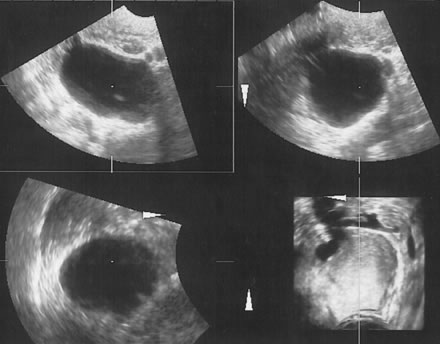

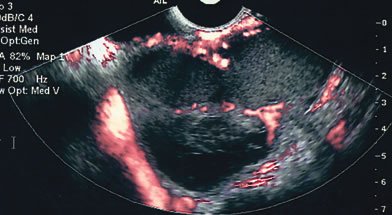

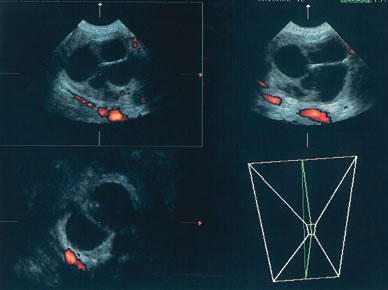

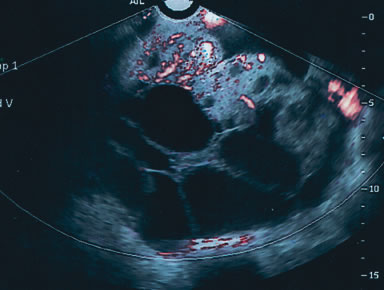

It is easier to assign the adnexal mass to one of to the five categories described by Osmers and coworkers9:

- Cystic

- Biloculated

- Multiloculated

- Complex

- Solid.

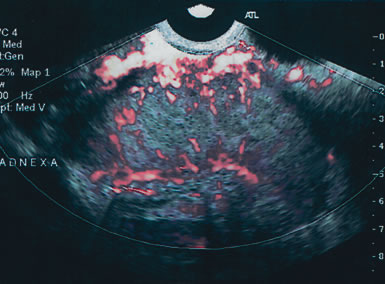

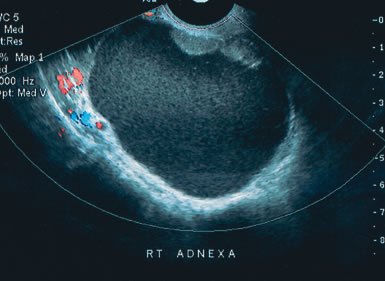

Examples of these categories are shown in Figures 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5. A mass is considered complex if it contains solid elements or thick or irregular septations, or if ascites is noted. Recent logistic regressions by Tailor and coworkers and Schelling and associates have confirmed that the presence of solid elements within a mass is the most predictive in identifying malignancy.10, 11 As shown in Table 1, most malignancies in Osmers's series occurred in the complex group. Osmers's system has a degree of subjectivity; a 5-cm thin-walled cystic mass with one or two thin septations could be categorized as either cystic or complex. This distinction ultimately depends on the informed judgment of the sonologist.

|

|

Table 1. Tumor Staging by Sonomorphologic Characteristics

| Simple |

|

|

|

|

Staging | Cystic | Bilocular | Multilocular | Complex | Solid |

Benign | 636 | 84 | 114 | 175 | 17 |

Borderline | 3 | - | 1 | 5 | - |

Malignant | 2 | - | 2 | 31 | 2 |

Osmers R, Osmers M, von Maydell B et al: Preoperative evaluation of ovarian tumors in the premenopause by transvaginosono-graphy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 175:428, 1996.