Breast cancer is the most common invasive (nonskin) cancer of women. For 2003, it is estimated that there will have been 211,300 invasive breast cancers diagnosed in women and 39,800 female deaths from breast cancer.1 In addition, 55,700 new cases of in situ breast cancer are estimated to be diagnosed in women in 2003.2

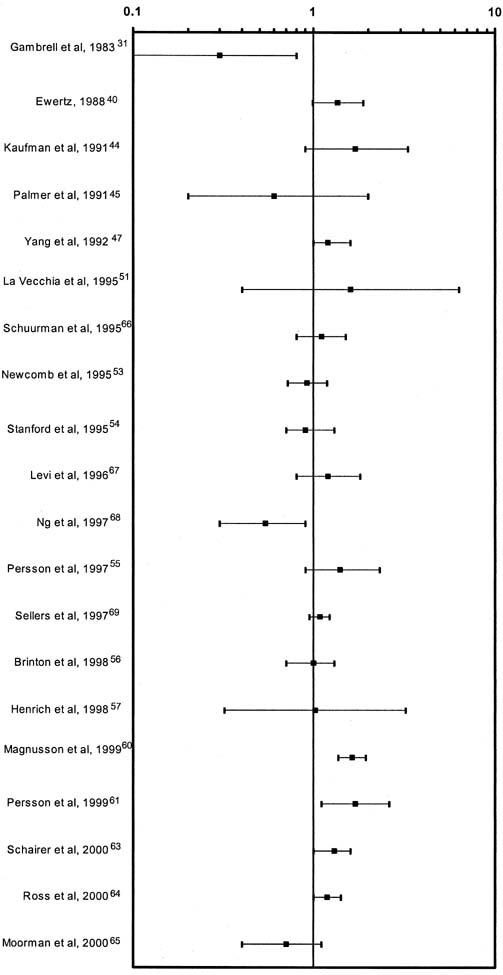

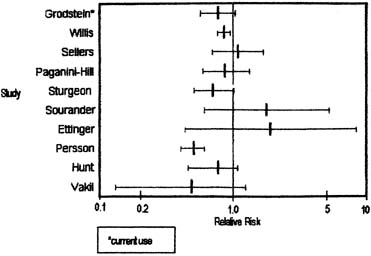

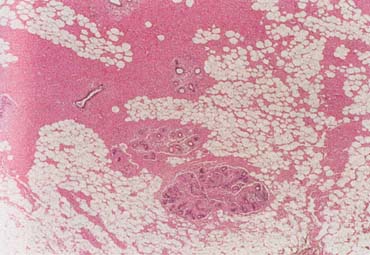

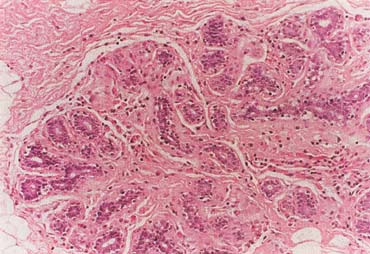

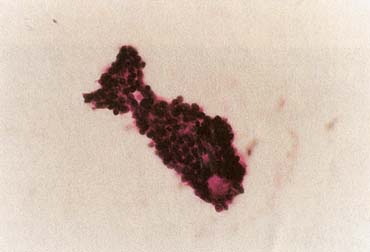

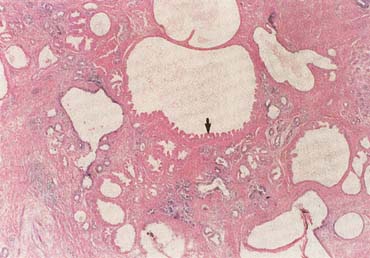

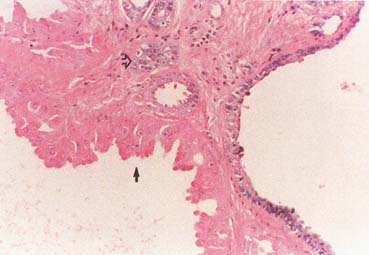

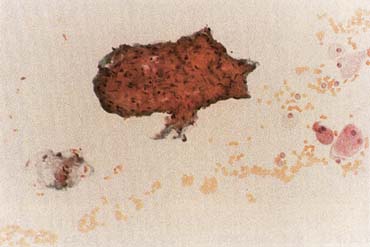

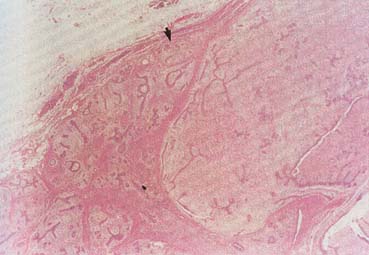

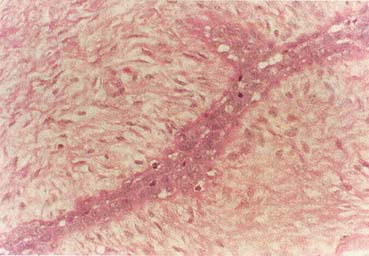

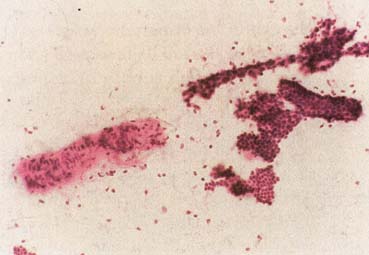

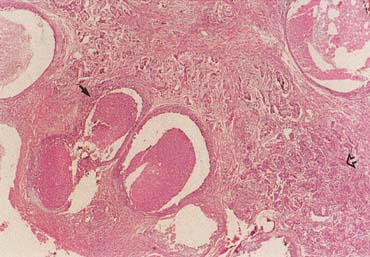

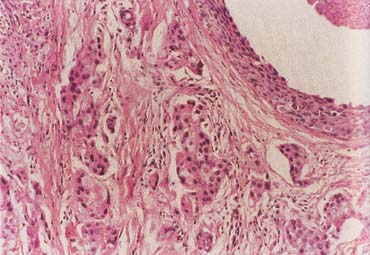

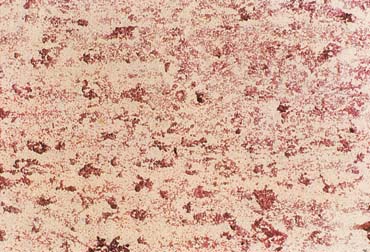

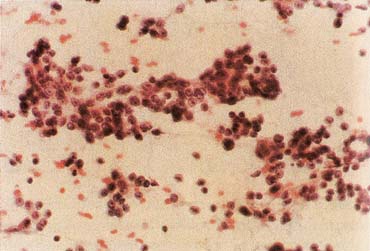

The American Joint Committee on Cancer lists 24 different codable histologic types of breast malignancies (Table 1), of which seven are in situ and 17 are invasive (infiltrating).3 Each specific histologic type has its own unique characteristics, biologic behavior, and prognosis when treated. In addition, the optimum treatment varies with each specific histologic type. However, for invasive and in situ breast cancer, as many as 80% of the cases are of the ductal type. Color plates 1 through 16 show typical examples of the histology and cytology of normal breast tissue, fibrocystic changes, fibroadenoma, and invasive ductal carcinoma under low- and high-power magnification. (Color plates appear at the end of the chapter.)

Table 1. Codable Histologic Breast Malignancies

| In Situ |

| Carcinoma in situ, NOS* |

| Comedocarcinoma, noninfiltrating |

| Cribriform carcinoma in situ |

| Intraductal carcinoma and lobular carcinoma in situ |

| Intraductal carcinoma, noninfiltrating, NOS |

| Lobular carcinoma in situ, NOS |

| Noninfiltrating intraductal papillary adenocarcinoma |

| Paget's disease and intraductal carcinoma of breast |

| Paget's disease, mammary |

| Invasive |

| Adenoid cystic carcinoma |

| Carcinoma, NOS |

| Carcinoma undifferentiated, NOS |

| Carcinosarcoma, NOS |

| Cribriform carcinoma, NOS |

| Infiltrating duct carcinoma, NOS |

| Inflammatory carcinoma |

| Lobular carcinoma, NOS |

| Medullary carcinoma, NOS |

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma |

| Paget's disease and infiltrating duct carcinoma of breast |

| Phyllodes tumor, malignant |

| Secretory carcinoma of breast |

| Squamous cell carcinoma, NOS |

| Tubular adenocarcinoma |

*NOS = not otherwise specified.

(Adapted from American Joint Committee on Cancer: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, p 236. 6th ed. New York, Springer, 2002.)

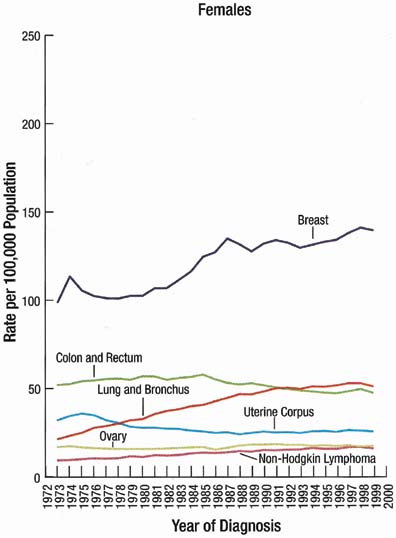

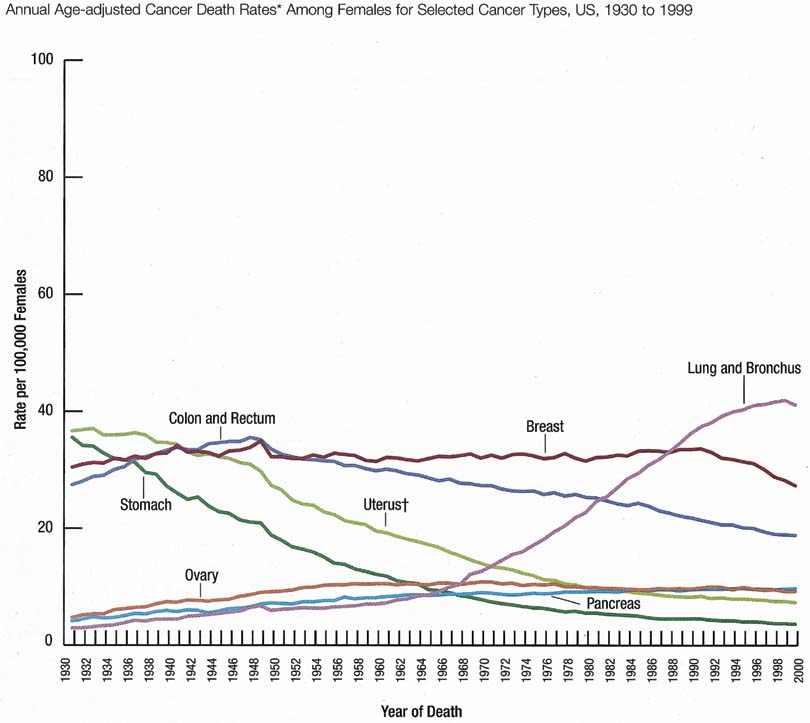

The incidence rate for breast cancer in women has increased steadily since 1977, as shown in comparison with other major invasive cancers in Figure 1.1 However, the incidence rate appears to have peaked in 1997, with a slight decrease since then. Figure 2 graphically depicts the contrasting mortality rates of the major invasive cancers.1 Possibly related to improved methods of treatment, the mortality rate for breast cancer has shown a continuous slightly downward trend of from 1940 to 1990. Probably caused by the widespread use of screening mammography, the mortality rate has decreased from 1990 to 1999. Hopefully, this trend of clinically meaningful decreasing mortality rates will continue as data for the years after 1999 become available. The 5-year survival rates by extent of breast cancer at the time of diagnosis are 86% for all stages, 97% for localized cancer, 78% for cancer with regional involvement, and 23% for metastatic cancer.2

Obstetrician-gynecologists should strive to bring about the diagnosis of breast cancer before the cancer is palpable. This goal can be effectively achieved by annual screening mammography for women beginning at age 40 years.4 Mammography can perceive small (1- to 9-mm) nonpalpable breast cancers that have the optimum curability, with more than 90% 20-year disease-specific survival using current methods of treatment (Table 2).5 Palpable cancers have a less favorable outcome. Generally, survival from palpable breast cancer correlates inversely with increasing size.6 For example, 10-to 29-mm cancers have been reported to have 67% 15-year survival (Table 3).7

Table 2. 20-Year Breast Cancer-Specific Survival: Mammographic

Appearance vs. Percentage Survival

| Mammographic Appearance | Percentage Survival |

| Stellate mass without calcifications | 100 |

| Noncasting calcifications | 96 |

| Circular mass without calcifications | 93 |

| Casting calcifications | 60 |

| All 1–9-mm tumors | 93 |

(Adapted by Patricia T. Kelly, Ph.D., from Tabar L, Vitak B, Chen HH, et al: The Swedish Two-County Trail twenty years later. Updated mortality results and new insights from long-term follow-up. Radiol Clin North Am 38:625–651, 2000.)

Tumors 1–9-mm without nodal involvement.

Table 3. 15-Year Breast Cancer Survival: Correlation With Tumor

Size

| Tumor Size | Percentage Survival |

| 10–14 mm | 86 |

| 15–19 mm | 72 |

| 20–29 mm | 67 |

| 30–39 mm | 46 |

(Adapted by Patricia T. Kelly, Ph.D., from Michaelson JS, Silverstein M, Wyatt J, et al: Predicting the survival of patients with breast carcinoma using tumor size. Cancer 95:713–723, 2002.)

Unfortunately, some cancers large enough to be palpable are not initially perceived on mammography. This probably occurs in less than 10% of cases.8 Increased mammographic density (Table 4) can obscure both nonpalpable and palpable breast cancers. Thus, women should have an annual clinical breast examination in addition to screening mammography. Ideally, the examination is performed before the mammogram so that the results of the examination are known by the radiologist/mammographer.

Table 4. The BI-RADS Descriptive Patterns of Mammographic Breast

Density

| The breast is almost entirely fat |

| There are scattered fibroglandular densities that could obscure a lesion on mammography |

| The breast tissue is heterogeneously dense |

| This may lower the sensitivity of mammography |

| The breast tissue is extremely dense, which lowers the sensitivity of mammography |

(American College of Radiology (ACR): Illustrated Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS™). 3rd ed. Reston, VA, American College of Radiology, 1998.)

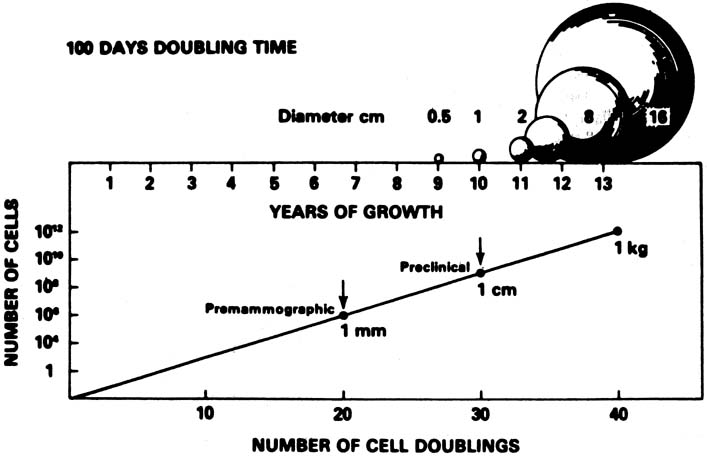

A conceptual mathematical model of the growth of a typical invasive ductal breast cancer is depicted in Figure 3.9 The growth of the cancer is based on a constant 100-day cell mass doubling time, which is the generally accepted mean rate of growth. However, estimated breast cancer doubling times have been reported in the range of 30 to 300 days and are not constant, but vary dependent on the specific cancer characteristics and host interaction. Nevertheless, the concept depicted is sound. There is a premammographic phase when the cancer is too small to be detected by any method currently available, followed by a preclinical phase when the cancer is too small to be palpable. Exactly when breast cancers metastasize is unknown, but the 90% 20-year disease-free survival of treated 1- to 9-mm mammographically detected cancers indicates that few had metastasized before the cancers reached a size of 1 cm. This concept underscores the importance of annual screening mammography particularly in the 40- to 49-year-old group in which, clinically, some of the breast cancers grow aggressively with apparently shorter doubling times.

The American Cancer Society's 2003 guidelines for the early detection of breast cancer in asymptomatic women are annual mammography and clinical breast examination beginning at age 40 and clinical breast examination every 3 years for women ages 20 to 39.10 If a clinically suspicious breast lesion remains undiagnosed, the patient should be urgently referred to a breast specialist. If the patient has diagnosed breast cancer, optimum treatment is usually obtained at a dedicated breast center with a multidisciplinary treatment planning team (Table 5).

| Imaging |

| Medicine |

| Nursing |

| Pathology |

| Plastic surgery |

| Radiation therapy |

| Social service |

| Surgery |