The Egyptians were the first to describe prolapse of the genital organs. The pessary was a known treatment.1 The word pessary frequently appears in both Greek and Latin literature, but in most instances it refers to a mechanical device in no way like the modern one. It usually meant a tampon, a ball of wool or lint soaked in drugs. However, Hippocrates mentioned the use of half of a pomegranate to be introduced into the vagina in instances of prolapse. Soranus likewise suggested the use of this fruit as a pessary and reports that Diocles was in the habit of supporting a prolapsed uterus by the introduction of half of a pomegranate previously treated with vinegar.2 Aurelius Cornelius Celsus (27 B.C.-A.D. 50) wrote of the use of pessaries in De Medicina.3 A bronze cone-shaped vaginal pessary with a perforated circular plate at its widest end was found at Pompeii. Supposedly, a band was attached to these openings and tied around the body to keep the device in place.2

About A.D. 326, Oribasius discussed pessaries, which he considered singularly useful for diseases of the uterus. There were three types of tampons: the emollient, the astringent, and the aperient. The astringent tampons were used for prolapse and were made of drug-saturated pledgets of cotton tied to string. These were placed snugly against the cervix.2

Paulas Aegina around A.D. 600 was touted as the first male midwife. He also used astringent pessaries made of wool dipped in medicine; he applied these to the mouth of the womb to restrain the female discharge, contract the womb when it was open, and impel it upward when it was prolapsed.3

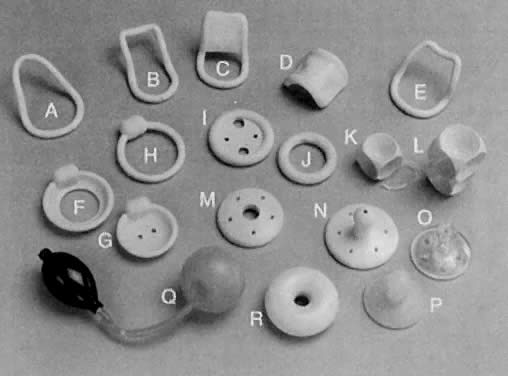

Trotula, the wife of Joannes Platearious, was the first recorded female practitioner of gynecology around A.D. 1050. She originated the use of a ball pessary that was made of strips of linen and filled the vagina in cases of prolapse.1 To complete the therapy, a T binder was applied. Caspar Stromayr of Lindau, Germany, recommended in 1559 that a sponge tightly rolled and bound with string, dipped in wax, and covered with oil or butter be substituted for a pomegranate as a pessary4 (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2).

|

|

Ambrose Pare, late in the 16th century, devised ingenious oval-shaped pessaries of hammered brass and waxed cork for uterine prolapse. He made an apparatus of gold, silver, or brass that was kept in place by a belt around the waist. He also designed pear-shaped and ring pessaries5 (Fig. 3). William Harvey was an exponent of the conservative school that treated prolapse with pessaries, replacement, and other such means unless carcinoma was present, when surgery was occasionally suggested. In his book, Anatomical Exercitations Concerning the Generation of Living Creatures (1653), he reported an enlarging and completely prolapsed uterus that contained a dead fetus.3

|

Hendrik Van Roonhuyse, born in 1622, was particularly interested in the diseases of women and made a remarkable contribution to 17th century gynecology when in 1663 he published Heelkonstige Aanmerkkingen Betreffende de Grebrecken der Vrouwen. This book often has been referred to as the first textbook on operative gynecology. Van Roonhuyse discussed the etiology and treatment of prolapse. An accepted procedure for treatment of prolapse was the use of cork with a hole in it to allow passage of discharges, plus wax pessaries or cork dipped in wax. He described one of the first complications and its resolution—his removal of one of these putrefied wax pessaries that had obstructed a patient's lochia.3 As noted in 1684 by Thomas Willis, “When at any time a sickness happens in a woman's body of an unusual manner so that its cause lies hid, and the curatory indication is altogether uncertain, presently we accuse the evil influence of the womb.”6

By the late 1700s, Thomas Simson, Professor of Medicine at the University of St. Andrew (Scotland), devised a metal spring that kept a cork ball pessary in place. Most pessaries had string attachments to facilitate removal. In instances of extensive perineal lacerations, pessaries were kept in place by T binders. These devices proved very unsatisfactory because friction injured the labia. 2 Conversely, John Leake had no use for pessaries, believing that rest and astringent applications were in every repect preferable to the use of those painful and indelicate instruments called pessaries. He advocated the use of sponges as pessaries to avoid vaginal wall injuries, which he noticed resulted from pessaries made of hard material. He extracted a pessary from the rectum of a patient at St. Thomas' Hospital.2 Mòrgagni recorded the autopsy of a woman with a pessary in situ.2 To avoid such complications, Jean Juville in 1783 introduced a soft rubber pessary. In devising this new type of pessary, Juville stated that it facilitated introduction by the patient. Juville's pessary resembled the contraceptive cup currently used. In the center of the cup was a perforated gold tip to permit the escape of cervical secretions. When he first introduced this new device, Juville was unable to state whether rubber was injurious to the vaginal tissue. Jean Astruc stated that the pessary had the same effect as a truss for a rupture. He believed that if the pessary were worn long enough and the patient grew fat, a cure would follow.2

Gynecologic faddism enjoyed its heyday throughout most of the 19th century. During the early decades, most of the ills of womankind were attributed to inflammations of the uterus. Toward the middle years, these views were supplanted by the Galenic doctrine that displacements of that organ were the principal cause of women's complaints. The pessary school of gynecology began to flourish. It was said that fortunes were to be made by two groups of gynecologists—those who inserted pessaries and those who removed them.7,8

Goodyear's discovery of the vulcanization of rubber was a boon to the purveyors and wearers of pessaries and greatly enhanced the popularity of the devices. Hugh Lenox Hodge, Professor of Gynecology at the University of Pennsylvania, was dissatisfied with the shapes of the existing pessaries. He set out to design a new one using Goodyear's newly patented material. The lever pessary was designed especially for cases of uterine retroversion. Hodge explained in 1860:

The important modification consists in making a ring oblong, instead of circular, and curved so as to correspond to the curvature of the vagina. Great advantages result from this form; the convexity of the curve being in contact with the posterior wall of the vagina, corresponds, with more or less accuracy, to properly arrange, there is no pressure against the rectum; and the higher the instrument rises, the superior extremity, instead of impinging against the rectum, passes upward and behind the uterus—between this organ and the intestine—giving a proper position to the womb, and yet allowing its natural pendulum-like motion to remain unrestrained9,10 (Fig. 4).

Albert Smith of Philadelphia later narrowed the anterior portion and widened the posterior end of the Hodge pessary.6

With the advent of asepsis and anesthesia, gynecologists' fascination with pessaries abated as uterine support deficiencies were addressed by surgery. Pessaries were used mainly for inoperable patients or as temporizing measures. Little progress was made in the development of new devices. Minor changes typically were made to existing pessaries and a new eponym attached. The most significant advance in the art and science of pessaries was the replacement of hard rubber by polystyrene plastics in the 1950s and recently by silicone-based materials.11