Patients clinically suspected of having ectopic pregnancy fall into two

major categories: those who have an acute abdomen and in whom immediate

surgery is indicated, and those who are clinically stable and in whom

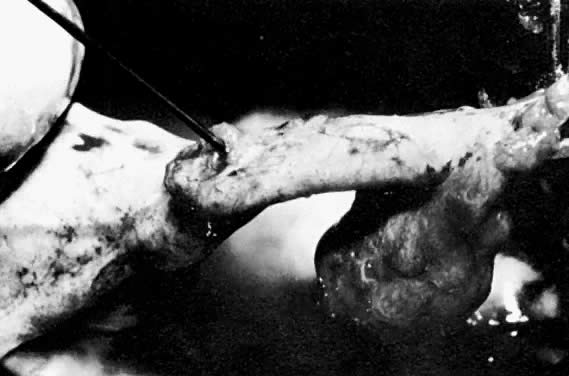

adjunctive diagnostic procedures can be performed. Patients with a surgical abdomen are evaluated in the emergency room with

rapid urine pregnancy tests and a culdocentesis. A positive culdocentesis

in a patient with a positive pregnancy test result has been reported

to correspond with ectopic pregnancy in 99.2% of cases.50 The results of a culdocentesis can be classified as negative, positive, or

nondiagnostic. A negative culdocentesis is indicated by the presence

of clear fluid. A positive result refers to the free flow of nonclotting

blood. If no fluid is obtained, the test is considered nondiagnostic. When

bloody fluid is obtained, a hematocrit of the aspirate is helpful. Ectopic

pregnancies are generally associated with hematocrits

of more than 15%. Lower hematocrits frequently indicate the presence of

cystic fluid. Traditionally, culdocentesis was considered useful in

the detection of a hemoperitoneum associated with a ruptured ectopic pregnancy. We

have found that most of the positive culdocenteses in our

institution are associated with an unruptured ectopic pregnancy. In such

cases, bleeding through the distal end of the fallopian tube results

in a hemoperitoneum. In our series, 86% of all positive culdocenteses performed in the emergency

room were associated with an ectopic pregnancy.50 Other causes of positive culdocentesis included ruptured ovarian cysts, retrograde

menstruation, endometriosis, torsion of the fallopian tube, and

bleeding of unknown etiology. It should be emphasized that a nondiagnostic

culdocentesis should not lower the suspicion of an ectopic

pregnancy. In our series, 16% of ectopic pregnancies had nondiagnostic

culdocentesis, and one quarter of these were ruptured at the time of

operation.50 Patients who will benefit most from a culdocentesis are those in whom a

clinical suspicion of ectopic pregnancy exists, and who present at a

time when expeditious diagnosis is desired and when sophisticated diagnostic

modalities, such as ultrasonography and sensitive human chorionic

gonadotropin (hCG) assays, cannot be obtained without significant delay. Under

these circumstances, culdocentesis is an inexpensive, rapid, and

easily performed means of patient evaluation that often provides

the impetus for immediate intervention. In clinically stable patients, a culdocentesis may be indicated when fluid

is visualized in the cul-de-sac at the time of ultrasound examination

of the pelvis. A positive culdocentesis dictates the need for a surgical

diagnosis. The procedure should not be overlooked in patients without

signs of peritoneal irritation. We have found that 45% of our patients

with a positive culdocentesis did not have rebound tenderness.50 The modern approach to the evaluation of clinically stable patients suspected

of having an ectopic pregnancy is based on the combined use of

sensitive pregnancy testing (or hCG testing), ultrasound examination, and

laparoscopy. hCG testing is used to screen for pregnancy, and ultrasonography

is employed to locate it.51 Evaluation of the patients begins with a sensitive and rapid pregnancy

test. Blood and urine pregnancy tests have been used to screen for ectopic

pregnancy. Traditional slide pregnancy tests have been found to have

a 15% to 50% false-negative rate in ectopic pregnancy, and for this

reason they are unsuitable for screening.52 Advances in technologies of enzyme-linked immunoassay and monoclonal antibodies

to the β subunit have promoted the evolution of rapid, inexpensive, and

similar qualitative urinary pregnancy tests. They are

expected to improve the accuracy of the old urine pregnancy tests. Meanwhile, as

the information for these tests becomes available, we prefer

to use the sensitive blood pregnancy testing in the form of a radioimmunoassay

against β-hCG. We recommend an assay with a sensitivity of 2.5 mIU/mL because with this

system the false-negative rate is 0.5%. The radioreceptor assay, with

a sensitivity of 200 mIU/mL, is not suitable for screening because its

false-negative rate ranges between 6% and 12%, which is unacceptably

high for a life-threatening condition.53,54 Other investigators using a urine hCG test with a stated sensitivity of 50 IU/L

support this test's clinical application in detecting ectopic

pregnancy in emergent conditions.55 A negative blood pregnancy test virtually rules out pregnancy and thus

an ectopic gestation. A positive result requires further investigation, requiring

a determination of the hCG titer and an ultrasonographic examination

of the pelvis. A positive diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy can be made if fetal motion is

demonstrated outside the uterus. Unfortunately, this is a rare and late

finding, and awaiting its appearance would delay the diagnosis and

conceivably increase the risk of tubal rupture. In practice, ultrasonography

is used to identify an intrauterine pregnancy, which would render

the simultaneous presence of an ectopic pregnancy extremely unlikely (1:30,000). Confirmation of the presence of an intrauterine pregnancy

can be made by identifying either a gestational sac or a fetal pole

within the endometrial cavity. The traditional ultrasonographic criterion used for the diagnosis of ectopic

pregnancy is failure to visualize a gestational sac in the uterus

of patients with more than 6 weeks of amenorrhea. The problem with this

criterion is that one third of patients with ectopic pregnancy do

not know the date of their last menstrual period, and in others irregular

bleeding makes interpretation of the menstrual history difficult. It has been established that the sac of a normal intrauterine pregnancy

becomes visible with ultrasonography when the hCG titer is greater than 6500 mIU/mL. When

levels are higher than this, the absence of a sac

is associated with an ectopic pregnancy in 86% of cases. This criterion

has a sensitivity of 100%, a specificity of 96%, and a negative predictive

value of 100%. The clinical application of this criterion includes

the fact that approximately 40% of women with an ectopic pregnancy

possess titers in excess of 6500 mIU/mL.50 The absence of a sac at levels less than 6000 mIU/mL is a nondiagnostic

finding and should not lower or raise the suspicion of ectopic pregnancy.56,57 Management of these patients depends on the clinical situation. If a patient

remains clinically stable, serial hCG determinations are used for

the assessment of such a patient and for deciding whether to proceed

to diagnostic laparoscopy. The presence of a sac below an hCG titer

of 6000 mIU/mL can be explained if the pregnancy develops beyond the level

of sac formation (above an hCG level of 6500 mIU/mL) and then stops

secreting hCG. A sac will be detected by ultrasonography when the hCG

titer has dropped below 6000 mIU/mL. Some normal intrauterine pregnancies

produce lower levels of hCG and therefore may show a gestational

sac at lower hCG concentrations. This may account for Nyberg and associates'58 detection of gestational sacs in 13 patients in whom the hCG titer was

less than 6000 mIU/mL. In addition, this discrepancy may be confounded

by the common use of two distinct hCG standards in the evaluation of

ectopic pregnancy. In 1974, the World Health Organization introduced

a new standard that involved the use of a more highly purified preparation

of hCG and subsequently established the International Reference Preparation (IRP). A

decade earlier, the second International Standard

had been introduced, but because of heterogeneity, it was often unsuitable

for use in many immunoassays.59 In comparing the two quantitative standards, clinicians should note that

the serum hCG titers determined by the IRP approximately double the

value calculated by the second International Standard. The hCG values

stated in this review are based on the IRP standard unless otherwise

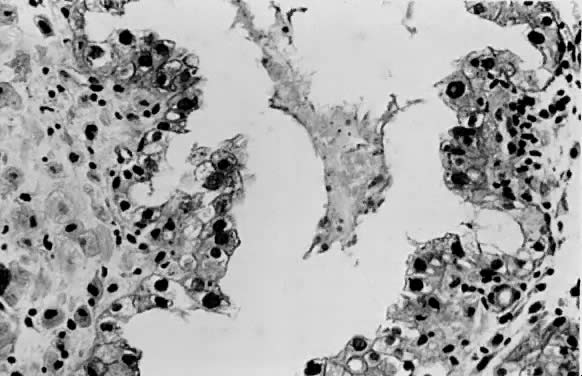

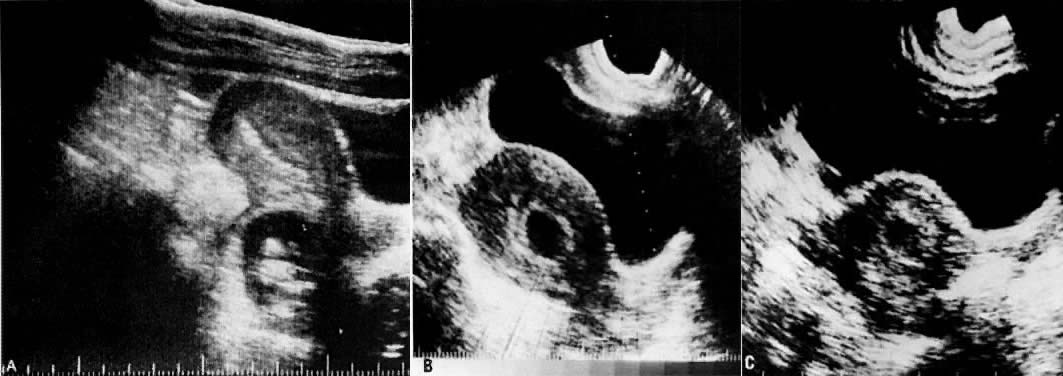

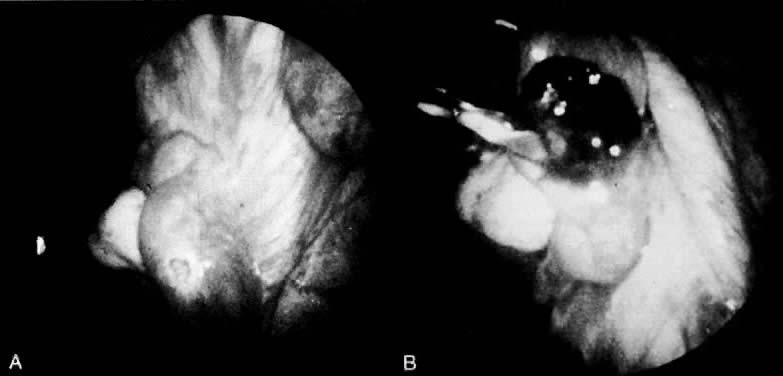

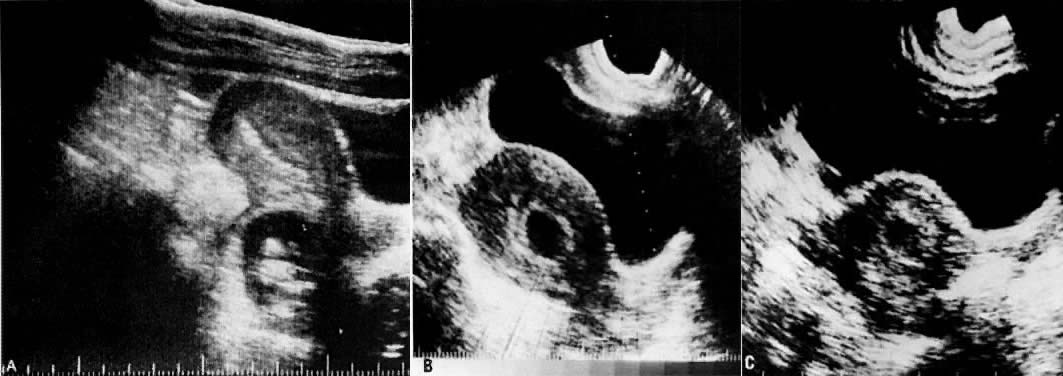

specifically noted. Finally, ectopic pregnancies can show a single-ring

sac due to the presence of blood within the endometrial cavity in association

with a significant decidual reaction. This appearance has been

shown to occur in 10% to 20% of all cases (Fig. 4).60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68  Fig. 4. A. Segmental scan of the pelvis in an ectopic pregnancy. A fetus is visualized

in the cul-de-sac. B. Gestational sac of two normal pregnancies. There is a double ring given

by the separation of the decidual capsularis and the decidual parietalis. C. Pseudogestational sac in an ectopic pregnancy. There is a single ring. Fig. 4. A. Segmental scan of the pelvis in an ectopic pregnancy. A fetus is visualized

in the cul-de-sac. B. Gestational sac of two normal pregnancies. There is a double ring given

by the separation of the decidual capsularis and the decidual parietalis. C. Pseudogestational sac in an ectopic pregnancy. There is a single ring.

|

Nyberg and colleagues69 and Bradley and associates70 have proposed morphologic criteria to distinguish the pseudogestational

sac of ectopic pregnancy from the gestational sac of a normal intrauterine

pregnancy. They have described the normal intrauterine gestational

sac as having a double contour produced by the decidua capsularis

and the decidua parietalis. The pseudogestational sac of an ectopic pregnancy

has only a single ring. The researchers have reported that 98.3% of

all patients with a double-ring sac had an intrauterine pregnancy

and 64 of 68 patients with a single-ring sac had ectopic pregnancies. Management of patients with an hCG titer less than 6000 mIU/mL is based

mainly on adnexal ultrasonographic findings and clinical suspicion. Romero

and colleagues71 prospectively evaluated 220 patients who were suspected of having ectopic

pregnancy and who had hCG titers less than 6000 mIU/mL and abdominal

ultrasonographic adnexal findings. The demonstration of a noncystic

mass, alone or associated with cul-de-sac fluid, was an indication for

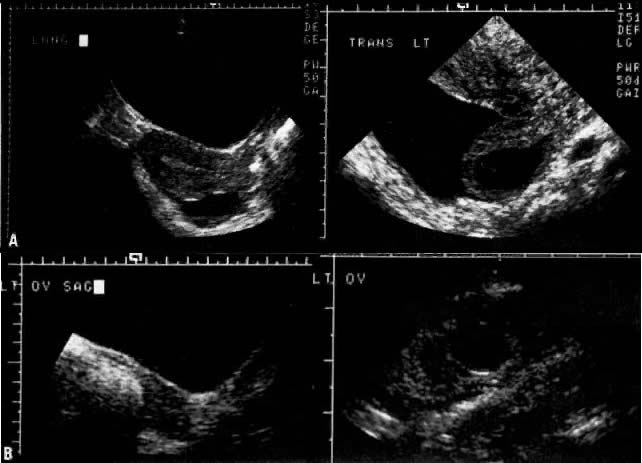

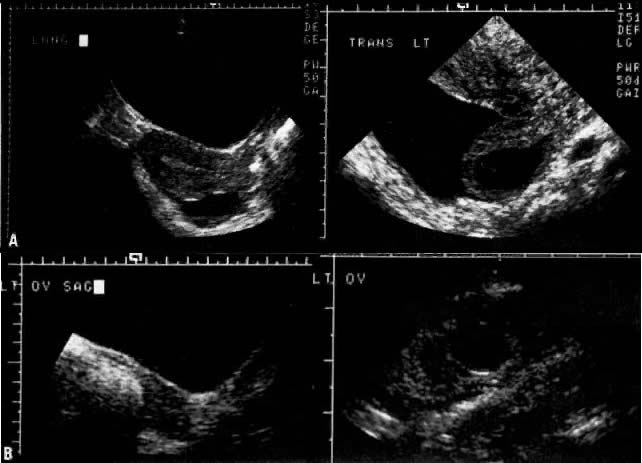

diagnostic laparoscopy. The value of transvaginal ultrasonography in the detection of ectopic pregnancy, especially

in cases of hCG titers less than 6000 mIU/mL, is

now recognized. Proximity of the ultrasound transducer to both the adnexa

and the cul-de-sac allows increased resolution and image quality with

the detection of an intrauterine pregnancy up to 7 days earlier than

with the classic transabdominal approach (Fig. 5).  Fig. 5. The increased sensitivity of transvaginal (right) versus transabdominal (left) ultrasonography in detecting an ectopic pregnancy. A. Proximity to the cul-de-sac allowed detection of this ectopic gestation (hCG

titer 880 mIU/mL) by means of transvaginal ultrasonography in this

patient. B. Transvaginal ultrasound permitted verification of a left infundibular

pregnancy missed on abdominal scanning in another woman (hCG titer 4146 mIU/mL) Fig. 5. The increased sensitivity of transvaginal (right) versus transabdominal (left) ultrasonography in detecting an ectopic pregnancy. A. Proximity to the cul-de-sac allowed detection of this ectopic gestation (hCG

titer 880 mIU/mL) by means of transvaginal ultrasonography in this

patient. B. Transvaginal ultrasound permitted verification of a left infundibular

pregnancy missed on abdominal scanning in another woman (hCG titer 4146 mIU/mL)

|

Vaginal scanning has proved to be more accurate than abdominal scanning

in detecting ectopic pregnancies (90% vs 80%) and cul-de-sac fluid (77% vs 46%) and

in discerning whether the tubal pregnancy has ruptured (76% vs 50%).72 In the transvaginal ultrasonographic evaluation of pregnancy, Bernaschek

and associates,73 using a 5-MHz transducer, proposed a “discriminatory zone” of

an hCG titer of 750 mIU/mL (second International Standard) for the

detection of an intrauterine gestational sac. Unfortunately, using this

proposed criterion and similar ultrasonographic equipment, Fossum and

associates74 may have inadvertently surgically investigated several pregnancies that

proved to be normal intrauterine gestations (Fig. 6). If an hCG titer exceeds 2000 mIU/mL, we now expect to detect an intrauterine

gestational sac using transvaginal ultrasonography.  Fig. 6. Relationship between transvaginal ultrasonographic findings and serum hCG

levels (range and mean ± SEM) using two World Health Organization

standards: the IRP and the second International Standard.(Fossum GT, Davajan V, Kletzky OA: Early detection of pregnancy with transvaginal

ultrasound. Fertil Steril 49:788, 1988. Reprinted with permission

of the publisher, The American Fertility Society) Fig. 6. Relationship between transvaginal ultrasonographic findings and serum hCG

levels (range and mean ± SEM) using two World Health Organization

standards: the IRP and the second International Standard.(Fossum GT, Davajan V, Kletzky OA: Early detection of pregnancy with transvaginal

ultrasound. Fertil Steril 49:788, 1988. Reprinted with permission

of the publisher, The American Fertility Society)

|

Even with the advent of transvaginal ultrasonography, the value of serial

hCG determinations cannot be overemphasized. If hCG titers increase

with time, Table 2 can be used to evaluate the normality of the increase. As a rule of thumb, the

hCG titer should increase by at least 66% of the initial titer

in a 48-hour period of observation.75 On the other hand, in asymptomatic women, declining hCG levels may be

indicative of a nonviable, nondetectable intrauterine gestation. Serum

progesterone values may prove a useful adjunct to hCG titers in distinguishing

a viable intrauterine pregnancy from that of an ectopic or missed

abortion. Accordingly, in two separate reports on 99 women, a progesterone

value less than 15 ng/mL was always predictive either of an

ectopic pregnancy or a nonviable intrauterine gestation.76,77 TABLE 2. Lower Limits of Percentage Increase of Serum hCG

Sampling Interval (Days) | Increase in hCG (%) |

1 | 29 |

2 | 66 |

3 | 114 |

4 | 175 |

5 | 225 | (Kadar N, Caldwell B, Romero R, A method of screening for ectopic pregnancy

and its indications. Obstet Gynecol 58:162, 1980)It should be emphasized that early intrauterine pregnancy failures may

not have enough tissue to be detectable by routine pathologic examination, and

therefore some patients with declining hCG titers will ultimately

prove to have intrauterine pregnancy failures. We recommend laparoscopy for patients with subnormal quantitative increases

of hCG. Normal increments in hCG are monitored until hCG titers exceed

either 2000 mIU/mL or 6500 mIU/mL, at which time either transvaginal

or transabdominal ultrasonography, respectively, may be performed. The

presence or absence of a gestational sac above these hCG levels

should be supportive either of an ectopic or an intrauterine gestation. Finally, if

hCG titers plateau, we perform a diagnostic laparoscopy

because the pattern is often characteristic of an ectopic pregnancy (Fig. 7).  Fig. 7. An algorithm for the management of an ectopic pregnancy. Fig. 7. An algorithm for the management of an ectopic pregnancy.

|

|