Topographic Anatomy and Surgical Landmarks

The intra-abdominal arrangement of the iliac vascular system can be projected on the abdominal surface. Beginning at a point 1/2 inch below and to the left of the umbilicus, draw a line inferolaterally so as to bisect a line running medially and inferiorly from the anterosuperior iliac spine to the middle of the symphysis pubis. The upper one third of the umbilicospinal line traces the course of the common iliac artery before its bifurcation. The distal two thirds of the same line delineates the external iliac artery; a line dropped medioinferiorly from this junction to the pelvic floor suggests the course of the hypogastric artery. The external bony landmark to the level of the bifurcation of the common iliac artery is the anterosuperior iliac spine. In most instances a line between both anterosuperior iliac spines bisects the points of bifurcation.

Internally, the aorta generally bifurcates into the common iliac arteries at the level of the fourth lumbar vertebra. The common iliac arteries, in turn, divide into the external and internal iliac (hypogastric) arteries. The external iliac artery courses along the psoas muscle laterally and ventrally to the leg, where it becomes the femoral artery. The hypogastric artery drops medioinferiorly along the border of the psoas muscle into the pelvis. An internal bony landmark for the level of the aortic bifurcation is the sacral promontory (lumbosacral articulation).

Once the hypogastric artery reaches the pelvis, it divides into the so-called anterior and posterior divisions. Those in turn divide into many branches, which are designated collectively as the hypogastric axis (Table 1). Figure 1 illustrates the gross anatomy.

TABLE 1. Branches of Internal Iliac Artery

Posterior Division | Anterior Division | |

Parietal | Parietal | Visceral |

Iliolumbar a. | Obturator a. | Umbilical a. (fetal) |

|

| Superior vesical a. |

Lateral sacral a. | Internal pudendal a. | Inferior vesical a. |

|

| Middle hemorrhoidal a. |

Superior gluteal a. | Inferior gluteal a. | Uterine a. |

|

| Vaginal a. |

Anatomic Relationships

The hypogastric arteries have important relationships to neighboring anatomic structures. Knowledge of these relationships facilitates locating the arteries, as well as dissecting and ligating them. These relationships, listed below, are illustrated in Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4.

|

|

- Anteromedially, the hypogastric (internal iliac) artery is covered by peritoneum; it

is a retroperitoneal structure. On the right side of the pelvis at this

point, the terminal end of the ileum and cecum may overlie the peritoneum.

- The ureter lies anterior to the hypogastric artery (retroperitoneal, attached to the undersurface

of the peritoneum).

- Posterolateral to the hypogastric artery are the external iliac vein and the obturator

vein.

- Posteromedial to the hypogastric artery is the hypogastric vein.

- Lateral to the hypogastric artery are the psoas muscles, major and minor.

Collateral Circulation

The collateral circulation of the pelvis has been the subject of discussion for at least a century. Gray's Anatomy (1870 edition) mentioned the many anastomoses. Anastomoses occur in each hemipelvis, horizontally and vertically across the pelvis.1, 2 The vertical system functions to a greater extent than the horizontal, especially after bilateral ligation. Figure 5 is a schematic representation of what might occur after unilateral ligation.

Three major vertical anastomoses exist in each hemipelvis: (1) lumbar-iliolumbar, (2) middle sacral, and (3) superior hemorrhoidal-middle hemorrhoidal. Bilateral ovarian-uterine anastomoses are another important vertical link. Anastomoses also occur between the inferior epigastric and medial circumflex femoral arteries, the circumflex and perforating branches of the deep femoral artery and the inferior gluteal artery, and the superior gluteal artery and the posterior branches of the lateral sacral artery.

The horizontal anastomoses are the branches of the vesical artery from each side and the pubic branches of the obturator artery from each side. Both systems are outlined in Table 2.

TABLE 2. Major Pelvic Anastomoses

Vertical

- Ovarian artery (branch of aorta) with the uterine artery

- Superior hemorrhoidal artery (branch of inferior mesen-teric) with middle

hemorrhoidal artery

- Middle hemorrhoidal artery with inferior hemorrhoidal (branch of internal

pudendal from hypogastric)

- Obturator artery with inferior epigastric artery (branch of external iliac)

- Inferior gluteal artery with circumflex and perforating branches of deep

femoral artery

- Superior gluteal artery with lateral sacral artery (posterior branches)

- Lumbar arteries with iliolumbar artery

Horizontal

- Branches of vesical arteries from each side

- Pubic branches of obturator from each side

Variations in the Pelvic Circulation

The forgoing anatomic descriptions suffice for practical purposes. Dissection of the branches of the hypogastric artery, however, frequently reveals variation in the number of branches, the relative size of the branches, and the length and diameter of the right and left hypogastric arteries.2, 3, 4 Figure 6 illustrates some of the documented variations in the branches of the hypogastric artery. Table 3 lists the collateral circulation of the branches of the hypogastric artery.

TABLE 3. Collateral Circulation of Branches of Hypogastic Arteries

Posterior Trunk | Anterior Trunk | ||

Branch | Collaterals | Branch | Collaterals |

Iliolumbar a. | Gluteal a. | Internal pudendal a. | External pudendal a. |

| Lumbar a. |

| Inferior gluteal a. |

| Lateral circumflex a. |

|

|

| Deep circumflex a. | Obturator a. | Middle circumflex a. |

| Spinal a. |

| Inferior epigastric a. |

|

|

| Iliolumbar a. |

|

|

| Inferior gluteal a. |

Lateral sacral a. | Spinal a. |

|

|

| Superior gluteal a. |

|

|

| Inferior gluteal a. | Inferior gluteal a. | Lateral circumflex a. |

| Middle sacral a. |

| Middle circumflex a. |

|

|

| First perforating a. |

Superior gluteal a. | Lateral sacral a. |

|

|

| Deep circumflex a. | Umbilical a. | Vesical a. |

| Inferior gluteal a. |

| Ureteric a. |

| Lateral circumflex a. |

|

|

|

| Uterine a. | Ovarian a. |

|

| Middle hemorrhoidal a. | Superior hemorrhoidal a. |

|

|

| Inferior hemorrhoidal a. |

The variations are relatively unimportant; however, some specific exceptions must be mentioned:

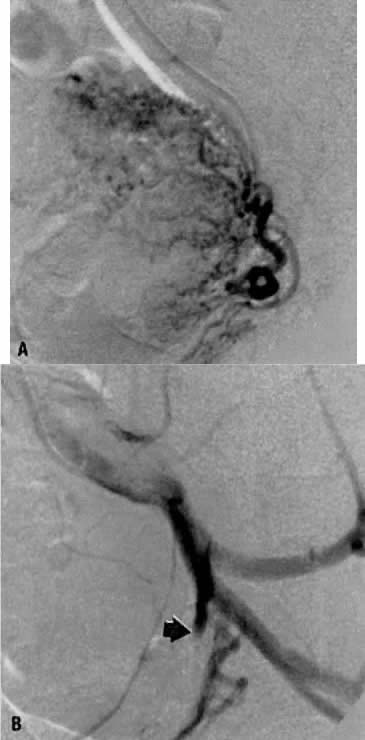

- Obstruction of the distal ureter by aberrant branches of the anterior division3: The obstruction usually is situated in the lower one third of the ureter

at a point midway between the bladder and the brim of the pelvis. Hydroureter

and dilatation of the renal calyces may occur in such cases; they

can be demonstrated by an excretory urogram. Significant clinical

symptoms are pain and discomfort in the loin on the affected side. Infection

secondary to stasis of urine is likely to be accompanied by

chills, fever, nausea, and hematuria. Therapy consists of surgical resection

of the aberrant vessel (Fig. 7).

- Failure of the distal hypogastric (umbilical) artery to atrophy: During fetal life, the hypogastric artery ascends from the pelvis along

the bladder and onto the back of the anterior abdominal wall, where

after joining its contralateral artery, it passes into the umbilicus as

the umbilical artery. At the time of birth, its function normally ceases; atrophy

converts the distal hypogastric artery into a fibrous cord

called the lateral umbilical ligament. In the absence of atrophic changes, however, ureteral

obstruction may develop.

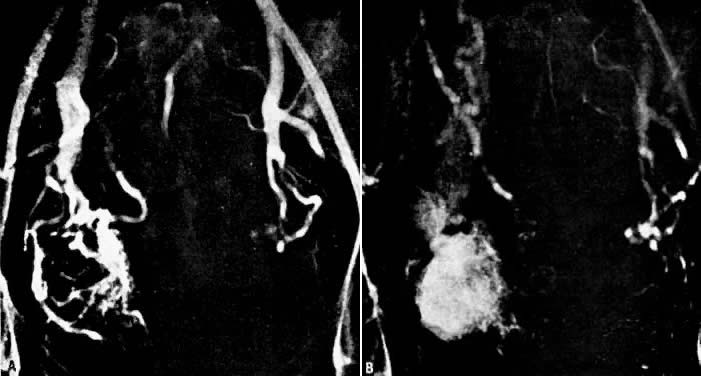

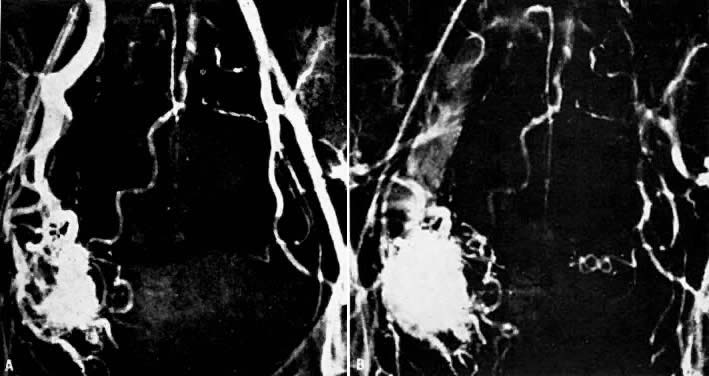

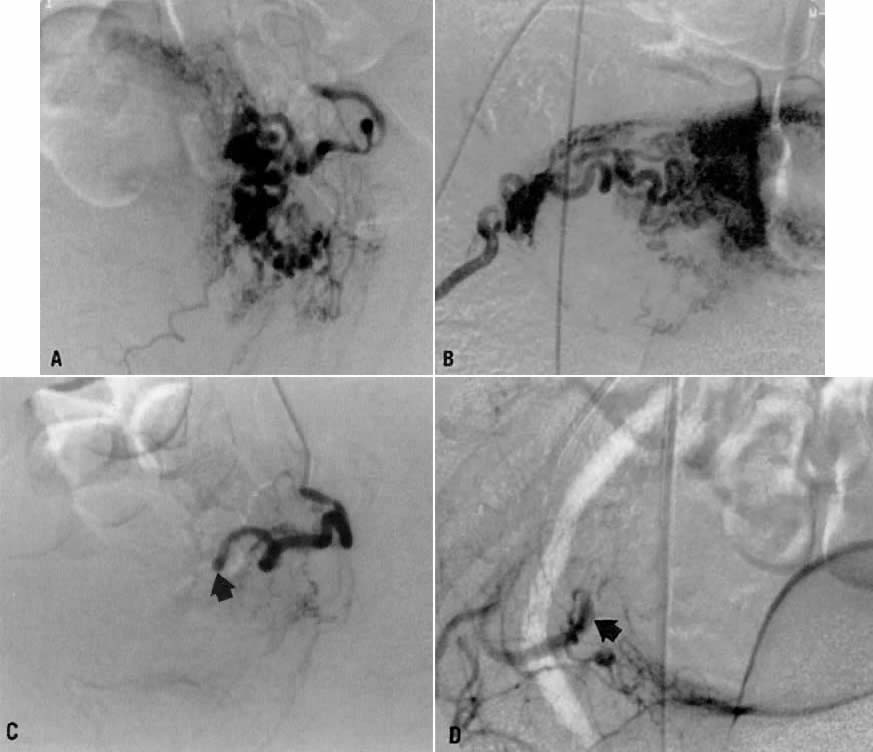

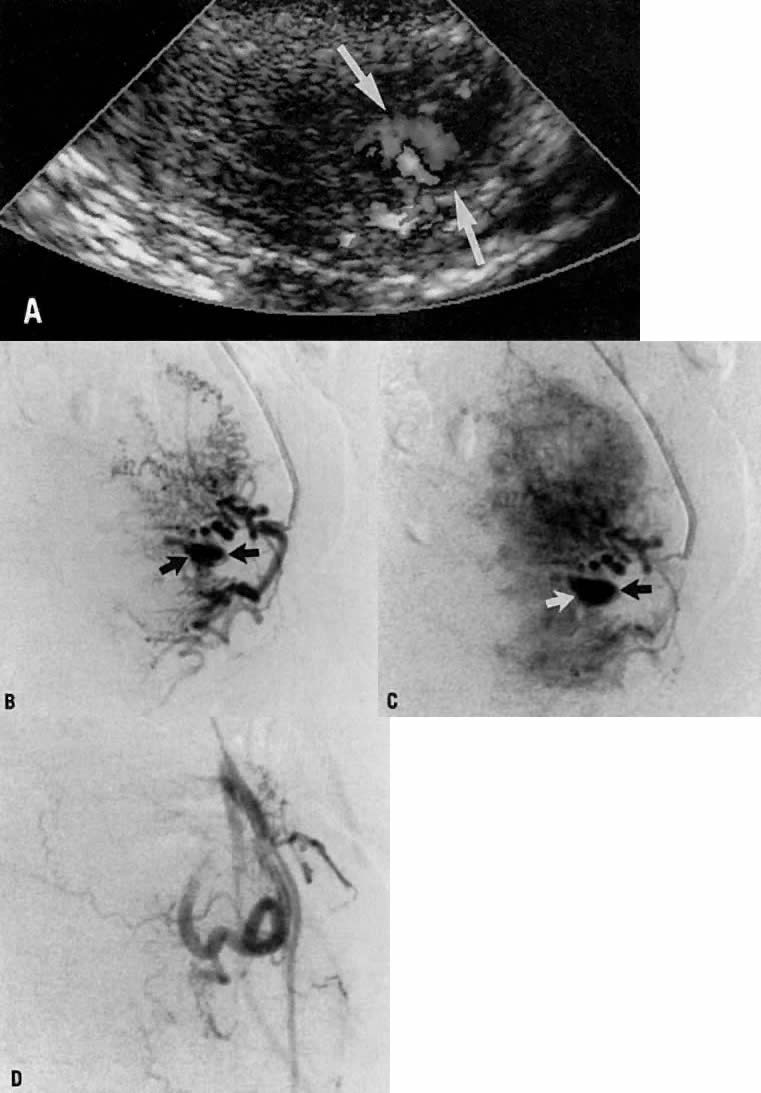

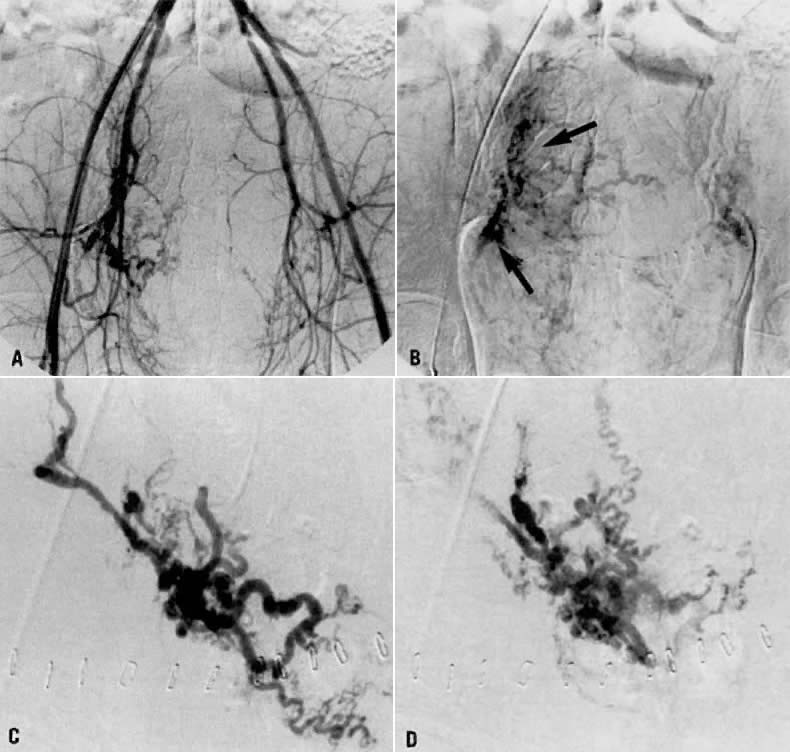

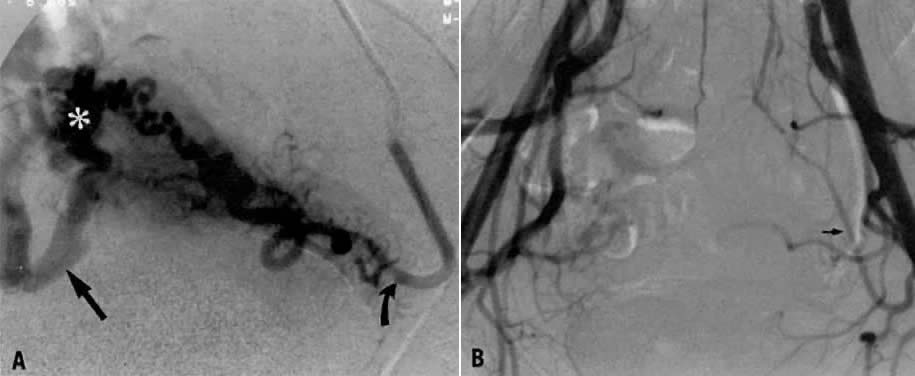

- Fistulous channels between branches of the hypogastric arteries and veins: Most patients with this rare condition have one or more of the following

signs and symptoms:

- Pelvic pain in the area of the fistula radiating to the back, vagina, or

down the posterior aspect of the leg on the same side

- A pulsatile mass with a bruit detectable vaginally or abdominally

- Edema of the legs

- Possible cardiac decompensation.

- Pelvic pain in the area of the fistula radiating to the back, vagina, or

down the posterior aspect of the leg on the same side

In the pregnant patient with this fistula, antepartum bleeding or abnormal enlargement of the uterus is probable. Severe, catastrophic hemorrhage has been reported in the postpartum period or after abortion. Percutaneous femoral aortography establishes the diagnosis. Therapy is achieved via surgery5 (Fig. 8 and Fig. 9)