Basic Tenets Safe and effective performance of open laparoscopy is based on four tenets: - Dissection of the minilaparotomy incision in layers and elevation of the

fascia and deeper layers during incision: Entering the abdomen using a knife without proper dissection and fascial

elevation increases the risk of complications. Bartsich and Dillon12 report cutting the superior mesenteric vein during the initial subumbilical

skin incision of an intended closed laparoscopy procedure.

- After visual confirmation of abdominal entry, insufflation of gas into

the abdomen directly through the cannula with the blunt obturator in place: This eliminates preperitoneal insufflation and shortens the time needed

to establish the pneumoperitoneum. The blunt obturator should not be

withdrawn until the abdomen is partially distended to avoid injury to

internal structures by the sharp edge of the bare cannula.

- Blocking the escape of gas from the abdomen: Loss of the pneumoperitoneum through gas leaks exposes the surgeon to

the risk of inadequate visualization and potential complication.

- Proper closure of the fascial defect at the end of the procedure: Proper fascial repair minimizes the occurrence of postoperative herniation.

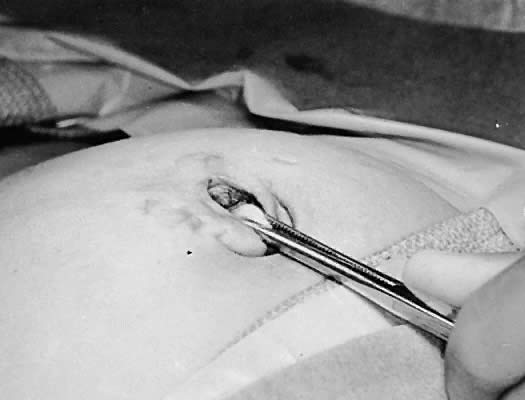

Procedure When satisfactory anesthesia has been achieved, the surgeon applies two

Allis clamps on the lateral margins of the umbilicus and makes a vertical

incision at the 6-o'clock position of the lower umbilical margin, extending

inferiorly for a distance of 1 to 2.5 cm (Fig. 6). The Allis clamps are repositioned on the skin edges to be used for retraction. Closed

scissors are introduced into the incision, and the blades

are separated several times to dissect connective tissue fibers

found between the skin and deep fascia. The surgeon directs a Kocher clamp

toward the upper angle of the incision and grasps the inferior margin

of the umbilical ring where the fascia is fused with the skin. The

surgeon lifts and everts the fascia and applies a second Kocher clamp

on it more inferiorly (Fig. 7). The fascia is clearly identified by separating it from surrounding fibrous, adipose, and

areolar tissue with blunt or sharp dissection. The

first Kocher clamp can be reapplied on the fascia to realize a more

secure purchase, as indicated.  Fig. 6. Stretching the skin and making a vertical incision. Fig. 6. Stretching the skin and making a vertical incision.

|

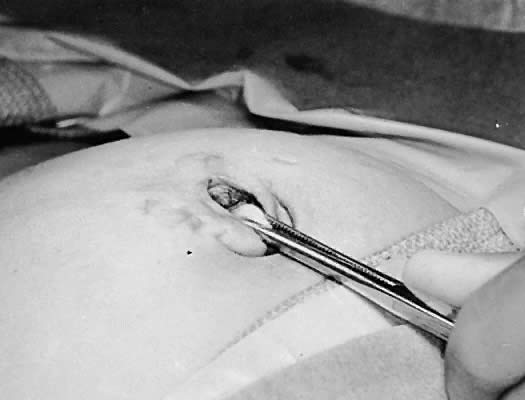

Fig. 7. Grasping the deep fascia close to its attachment to the skin and lifting

it upward and superiorly. Fig. 7. Grasping the deep fascia close to its attachment to the skin and lifting

it upward and superiorly.

|

The surgeon raises the deep fascia with the Kocher clamps and incises the

fascia carefully between the clamps while maintaining fascial elevation. Raising

the fascia separates the abdominal wall from the bowel and

omentum and minimizes the possibility of inadvertent damage during

fascial incision. The initial size of incision need not exceed 0.5 cm. The

incision then is enlarged using a spreading hemostat. Usually, the

peritoneum is entered by the spreading hemostat. Otherwise, the flat

end of one S-shaped retractor is introduced into the incisional gap and

is pressed against the peritoneum for abdominal entry (Fig. 8). The surgeon passes a suture through each fascial edge and tags it. The

S-shaped retractor lodged within the incision acts as a backstop to

the needle. The second S-shaped retractor then is placed through the

fascial gap into the peritoneal cavity, and the abdominal wall is raised

with both retractors to confirm peritoneal entry by viewing the bowel

and omentum. If the surgeon discovers that the abdominal cavity had

not been entered, the surgeon identifies and retracts the rectus muscle, exposes

the peritoneum, and enters it with a thrust of a small hemostat. The

hemostat is opened inside the peritoneal cavity, and a retractor

is placed in the abdomen between the open jaws of the hemostat. The

hemostat is removed, and the other retractor is applied on the opposite

side. Occasionally, abdominal entry is not possible with the previously

described procedures because of the presence of a well-developed

Richet's fascia. In this case, the surgeon should lift Ricket's

fascia and peritoneum with two hemostats and incise them carefully

to avoid nicking the small bowel. In any case, the surgeon must confirm

peritoneal entry through visualization of the small bowel or omentum.  Fig. 8. Enlarging the fascial incision with the spread of a hemostat and placement

of an S-shaped retractor. Fig. 8. Enlarging the fascial incision with the spread of a hemostat and placement

of an S-shaped retractor.

|

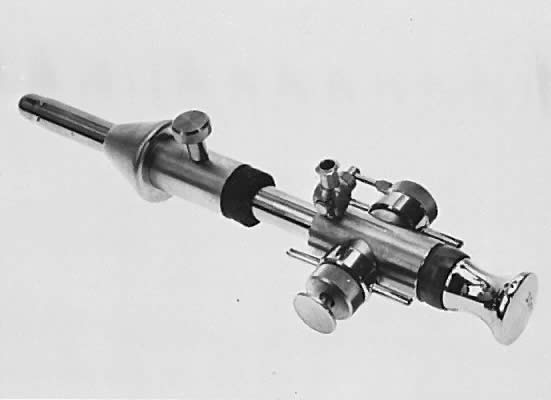

The surgeon prepares the open laparoscopy cannula for insertion by sliding

the cone sleeve over the shaft and locking the cone in a position

consistent with the individual thickness of the abdominal wall. The cannula

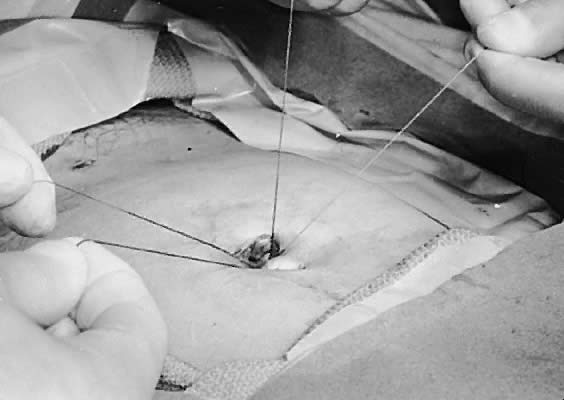

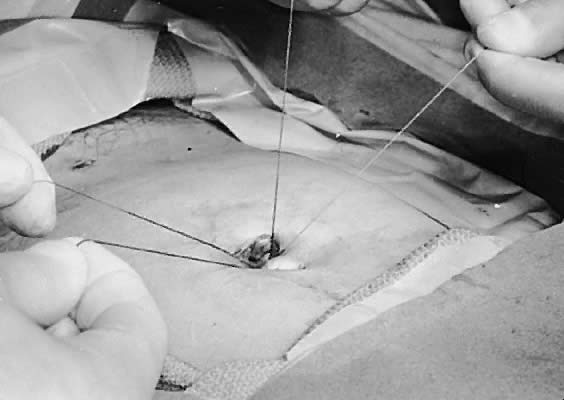

then is introduced between the retractors into the abdominal cavity (Fig. 9). The fascial tag sutures are held tensely upward and threaded into the

V-shaped suture holders (Fig. 10). This maneuver fixes the cannula on the abdominal wall and pulls the

fascia against the cone to prevent escape of the gas (Fig. 11). Gas insufflation is initiated during threading of the fascial tag sutures

into the suture holders. The blunt obturator is removed to permit

a rapid flow of the gas.  Fig. 9. Introducing the open laparoscopy cannula into the abdomen, guided by the

S-shaped retractors. Fig. 9. Introducing the open laparoscopy cannula into the abdomen, guided by the

S-shaped retractors.

|

Fig. 10. Fixing the fascial tag sutures into the V-shaped suture holders. Fig. 10. Fixing the fascial tag sutures into the V-shaped suture holders.

|

Fig. 11. Creation of an airtight seal following pulling of the sutures snugly into

the holders. Fig. 11. Creation of an airtight seal following pulling of the sutures snugly into

the holders.

|

The surgeon introduces the laparoscope, with or without an attached camera, through

the open laparoscopy cannula and performs the intended procedure. When

the endoscopic procedure is completed, the surgeon deflates

the distended peritoneal cavity, withdraws the cannula, and closes

the abdominal wall in two layers. The fascial tag sutures are used to

approximate the fascia. The surgeon positions the sutures in parallel

alignment (Fig. 12), ties a square knot on one side (Fig. 13), pulls the tied suture against the fascia, and ties a second knot on

the opposite side of the fascia (Fig. 14). The skin is approximated loosely.  Fig. 12. Alignment of the superior and inferior tag sutures parallel to each other. Fig. 12. Alignment of the superior and inferior tag sutures parallel to each other.

|

Fig. 13. Tying the first knot combining fascial tag sutures on the left side of

the patient. Fig. 13. Tying the first knot combining fascial tag sutures on the left side of

the patient.

|

Fig. 14. Tying the second knot combining fascial tag sutures on the right side of

the patient, effecting closure of the fascia. Fig. 14. Tying the second knot combining fascial tag sutures on the right side of

the patient, effecting closure of the fascia.

|

Technical Pitfalls Although open laparoscopy is a simple operation, there are several pitfalls

that increase technical difficulty. These are outlined in Table 1. TABLE 1. Technical Pitfalls in Open Laparoscopy

Pitfall | Reason | Remedy |

Skin incision is made too small for degree of surgeon's experience

or patient obesity. | Ease of operation is inversely related to size of skin incision. | To improve exposure, enlarge skin incision to maximum of 2.5 cm |

Retraction is applied upward on angle greater than 60 degrees. | Such upward retraction increases distance to operative site and diminishes

view. | To improve exposure, apply retraction force at projected angle of 45 degrees

or less. |

Failure to raise fascia during incision | Possible injury to deeper structures | To increase safety, maintain fascial elevation during incision |

Fascial incision is not enlarged with hemostat. | It is difficult to pass sutures into fascial edges that are not clearly

visible. | To clearly expose the fascial edges and peritoneum, enlarge the fascial

gap |

| It is also difficult to expose or enter peritoneum through minute fascial

gap. | |

Use of weak needles and sutures or use of large needles | Needle may break inside operative field. | To avoid breakage and to enhance ease of manipulation, use a small, strong

needle attached to suture of adequate tensile strength |

| Sutures may break while being threaded in suture holders. Large needle

is awkward to use in small operative field. | |

Failure to stabilize cannula while threading the fascial sutures into suture

holders | Cannula may be dislodged into properitoneal space while fascial sutures

are being pulled upward. | To prevent cannula from being displaced, press it gently against abdominal

wall as fascial sutures are being pulled upward |

Failure to pull fascial sutures tensely into suture holders | Lax fascial sutures do not pull fascial edges snugly against cone of cannula. Gas

may excape. | To create an airtight seal, hold fascial sutures taut as they are wedged

into suture holders | Other Procedures Using Similar Concepts Several operations applying similar concepts of abdominal entry for laparoscopy

have been proposed. These procedures use a standard laparoscopic

cannula, not the open laparoscopy cannula. The modified techniques

of open laparoscopy are safe and effective to the extent that they observe

the basic tenets of the procedure and succeed in providing an airtight

seal around the cannula. Additionally, care must be exercised while

introducing the cannula into the abdomen without a protective blunt

obturator to avoid internal injury by the sharp edge of the bare cannula. Examples of methods described to block escape of the gas around a standard

cannula include using a purse-string suture in the fascia (with or

without a rubber tube choker)13, 14 or in the subcutaneous tissue,15 and applying towel clips,16-18 Allis clamps,19 or suture20 to the skin and subcutaneous tissue surrounding the cannula. |