Despite decades of research directed at the problem of early diagnosis of ovarian cancer, most cases are still not detected before metastasis. Although the development of serum tumor markers31 and sensitive imaging techniques such as vaginal color-flow sonography32 have focused attention on the problem of early detection, neither method has been proved effective as a screening tool for the general population or even for a high-risk population.

As a result of the lack of effective methods for early diagnosis and the fact that ovarian cancer produces no specific symptoms in its early stages, patients often present with obvious ascites and palpable tumor masses in the pelvis and upper abdomen. On exploration, it is usually impossible to resect all gross tumors, and such disease certainly cannot be cured by surgery alone. The surgeon confronted with such a situation must decide what level of surgical aggressiveness is appropriate. For many human tumors, aggressive surgery can be justified only if all known tumor can be removed, thus making the operation at least potentially curative. For epithelial cancer of the ovary, however, there is considerable theoretic and clinical evidence that cytoreduction, or debulking, of large tumor masses may be beneficial to the patient even if all gross tumor cannot be removed.

The theoretic evidence in support of debulking comes largely from concepts of the kinetics of tumor cell growth and the mechanisms of tumor cell destruction by cytotoxic chemotherapy. For diseases in which chemotherapy is essentially ineffective, such as certain gastrointestinal malignancies, the concepts of cytoreduction do not hold. In ovarian cancer, however, the cancer cells are usually sensitive to chemotherapy, and the removal of large tumor masses may improve the response to subsequent chemotherapy. The blood supply of these masses may be relatively poor, especially centrally. Although poor blood supply can ultimately cause central necrosis of the tumor mass, it can also lead to the development of adjacent areas of viable tumor that cannot be reached by adequate concentrations of chemotherapeutic agents. Additionally, cells in masses with a poor blood supply tend to have a low growth fraction and a higher proportion of cells in the nonproliferating (Go) phase of the cell cycle, making them relatively insensitive to the effects of chemotherapy.33 The removal of large tumor masses may actually decrease the number of cycles of chemotherapy required to eliminate all remaining tumor cells.

Skipper and associates34 demonstrated the phenomenon of fractional cell kill, which applies to tumors that grow in an exponential fashion. In this phenomenon, a given dose of a cytotoxic agent will kill a constant fraction of the tumor, rather than a constant number of tumor cells, regardless of the initial cell population. Although solid tumors such as ovarian cancer do not grow in a true exponential fashion, it is still likely that surgical reduction of tumor burden may reduce the number of cycles of chemotherapy that are needed. The likelihood of acquired chemoresistance caused by exposure of the tumor cells to the cytotoxic agent will therefore be decreased, as will the risk for chemotherapy-related toxicity. According to the mathematical model of Goldie and Coldman,35 resistance to cytotoxic drugs occurs in part as a result of random, spontaneous mutations of tumor cells to drug-resistant phenotypes. Such mutations occur at a frequency relative to the number of tumor cells. Cytoreductive surgery may eliminate existing resistant tumor clones and decrease the spontaneous development of new resistant clones.

In addition to increasing the response to chemotherapy, effective cytoreduction may improve the patient's comfort by improving or restoring intestinal function and decreasing the formation of ascites. The patient will be better able to maintain adequate nutrition and reduce the adverse metabolic consequences of the tumor, which in turn can increase her ability to withstand intensive combination chemotherapy. Blythe and Wahl36 reported improvement in the quality of life of patients who had undergone successful cytoreductive surgery. These patients were more likely to be able to continue their normal activities, including employment, compared with the patients who did not undergo aggressive cytoreduction. Nearly 80% of the patients who underwent optimal cytoreduction were able to tolerate a regular diet, compared with only 40% of patients who had suboptimal surgery. Morton37 proposed that debulking might be beneficial in terms of decreasing the immunosuppression caused by the tumor.

Clinical studies that support debulking now span more than two decades and include patients treated with radiotherapy, nonplatinum-based chemotherapy, and platinum-based combination regimens, suggesting that all of these treatments are more effective in patients with small tumor burdens. In 1968, Munnell,38 who developed the concept of “maximal surgical effort” for ovarian cancer, reported that patients who underwent a “definitive operation” had an improved survival rate compared with patients who had “partial removal” or “biopsy only.” In a 1969 report, Elclos and Quinlan39 reported that 25% of patients with stage II ovarian cancer whose disease was surgically reduced to “nonpalpable” survived, compared with 9% of those left with “palpable” disease.

The measures of cytoreduction and residual disease used in these early studies were obviously quite crude. Griffiths,40 in a seminal report published in 1975, was the first to quantify accurately the amount of residual disease after the primary operation for ovarian cancer and to attempt to correlate this with outcome after chemotherapy. Reporting on 102 patients who received alkylating agent chemotherapy for stage II or stage III ovarian cancer, he demonstrated with the use of a linear regression model that survival duration was significantly related to the size of the residual tumor at the completion of primary debulking. In his report, patients with no residual tumor had a median survival of 39 months, compared with 12.7 months for patients with residual tumor of greater than 1.5 cm in maximum diameter. Griffiths also made the important observation that aggressive resection of bulk tumor without removal of all tumor masses greater than 1.5 cm in diameter did not improve survival.

Subsequent reports of clinical trials of both nonplatinum-based combination regimens41 and platinum-based regimens42 have supported the concept of debulking. Reports from many institutions have evaluated the effect of surgical cytoreduction in ovarian cancer. Patients undergoing optimal cytoreduction are generally shown to have an increased chance of negative surgical reexploration after chemotherapy,43 an increase in median survival,44 and a decrease in the rate of recurrence after a negative second-look operation.45 Table 5 shows a compilation of 10 reports,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55 comprising a total of 1012 patients, that demonstrates the effect of the amount of residual disease after primary cytoreduction on the frequency of negative surgical reexploration after chemotherapy (second-look laparotomy). Table 6, based on data from nine reports,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64 shows the effect of the amount of residual disease on median survival in patients with advanced ovarian cancer treated with chemotherapy.

| Percent Negative by Initial Residual | |||||

| First Author | Year | Patients (N) | None | Optimal* | Suboptimal* |

| Barnhill | 1984 | 0096 | 67 | 61 | 14 |

| Berek | 1984 | 0056 | – | 41 | 12 |

| Podratz | 1985 | 0135 | 82 | 44 | 39 |

| Smirz | 1985 | 0088 | 75 | 37 | 19 |

| Cain | 1986 | 0177 | 76 | 50 | 28 |

| Dauplat | 1986 | 0051 | 85 | 73 | 19 |

| Gallup | 1987 | 0065 | 71 | 63 | 13 |

| Carmichael | 1987 | 0146 | 62 | 30 | 25 |

| Lippman | 1988 | 0067 | – | 49 | 07 |

| Lund | 1990 | 0131 | 77 | 55 | 25 |

| Total | 1012 | ||||

| Weighted Mean | 75 | 48 | 22 | ||

*As defined by each author.

| Median Survival (in Months) According to Amount of Residual Tumor | |||

| First Author | Year | Optimal* | Suboptimal* |

| Pohl | 1984 | 450 | 16 |

| Conte | 1985 | 25+ | 14 |

| Posada | 1985 | 30+ | 18 |

| Louie | 1986 | 240 | 15 |

| Redman | 1986 | 370 | 26 |

| Neijt | 1987 | 400 | 21 |

| Hainsworth | 1988 | 720 | 13 |

| Piver | 1988 | 480 | 21 |

| Sutton | 1989 | 450 | 23 |

| Mean | 410 | 18 | |

*As defined by each author.

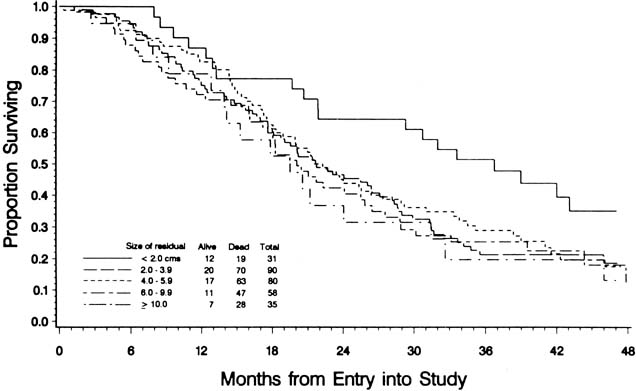

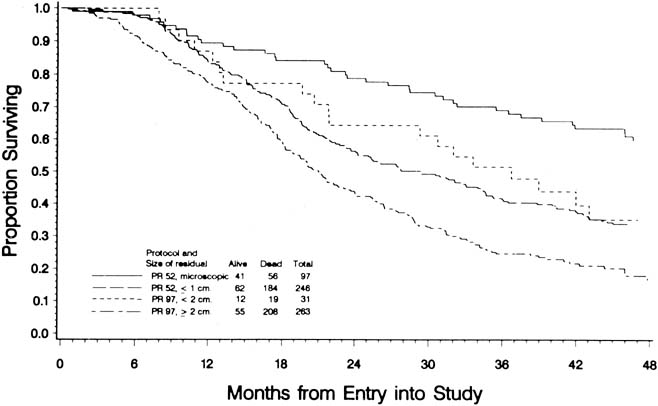

To evaluate the effect of residual disease on survival, Hoskins and colleagues65 reviewed data on 458 patients treated in accordance with a GOG protocol that evaluated standard versus high-dose chemotherapy with cisplatin and cyclophosphamide in suboptimal (residual disease greater than 1 cm) stage III and stage IV epithelial ovarian cancer. They found that patients with residual disease of 1 to 2 cm had better survival than patients with disease greater than 2 cm (Fig. 1). They found that cytoreduction that did not achieve residual disease of less than 2 cm had little effect on survival. When they combined the results of this analysis with an analysis of a similar GOG protocol (cisplatin and cyclophosphamide versus a cisplatin, cyclophosphamide, and doxorubicin combination) that enrolled patients with optimal (residual disease less than 1 cm) stage III epithelial ovarian cancer, they found that survival at 48 months was 58% for microscopic disease, 34% for residual gross disease up to 2 cm in diameter, and 16% for patients with residual disease greater than 2 cm (Fig. 2).

|

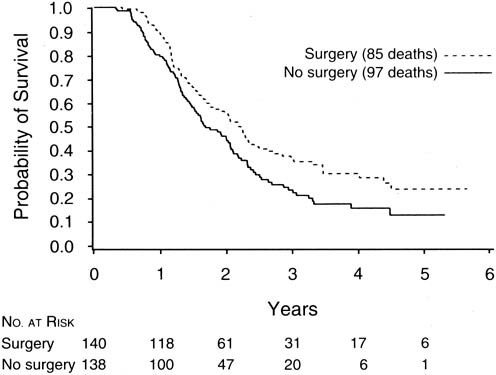

The finding of Hoskins and coworkers that disease that could not be cytoreduced to less than 2 cm in diameter was associated with uniformly poor survival and should be viewed in relation to a study of interval cytoreductive surgery by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer reported in 1995 by Van der Burg and associates.66

These authors randomized patients with suboptimal disease that could not be cytoreduced to six cycles of cisplatin and cyclophosphamide versus three cycles of the same chemotherapy followed by interval cytoreductive surgery. The surgical patients then received an additional three cycles of cisplatin and cyclophosphamide. They found a median survival of 26 months for patients undergoing interval cytoreduction versus 20 months for those who did not (p = .012) (Fig. 3).

|

Patients who present with suspected ovarian cancer should undergo the routine preoperative tests before any major operation, including a complete blood count, biochemical profile, chest radiograph, and electrocardiogram. In addition, special radiographic studies such as computerized tomography, ultrasonography, or magnetic resonance imaging may be helpful in confirming the presence of a mass and identifying ascites or other evidence of metastatic disease. Intestinal imaging studies or upper and lower endoscopy is performed if there is clinical suspicion of a gastrointestinal primary tumor. Most gynecologic oncologists use a regimen of mechanical and antibiotic bowel preparation to cleanse the intestine in case intestinal resection is necessary or the bowel is entered inadvertently. Many gynecologic oncologists also use a regimen of low-dose subcutaneous heparin or intermittent calf compression devices to prevent deep vein thrombosis and perioperative intravenous antibiotics to decrease infections.

Before surgery, the patient and her family should be counseled thoroughly about the risk of malignancy and the surgical procedures that might be necessary. If there is a suspicion of rectal involvement, the possibility of low rectal anastomosis should be mentioned. Although a colostomy is always possible, it is rarely performed during primary cytoreductive surgery. The patient should also understand that although every attempt will be made to remove as much tumor as possible, advanced ovarian cancer cannot be cured by surgery alone, and chemotherapy will be necessary.

The abdomen should be opened through a vertical incision extending from the pubic symphysis to well above the umbilicus to allow access to the upper abdominal structures. If ascites are present, a sample should be taken for cytologic analysis. If no ascites are present, saline washings may be obtained. Before undertaking any pelvic operation, a complete exploration of the upper abdomen should be performed, with particular attention to the hemidiaphragms and omentum. The stomach and the small and large intestines should be evaluated, as should the retroperitoneal structures, including the lymph nodes, pancreas, and kidneys. An estimate of the resectability of upper abdominal disease may be important in determining the appropriate procedure for dealing with the pelvic tumor. In evaluating the pelvis, the surgeon must consider whether the primary tumor in the ovaries can be completely removed, the extent to which hysterectomy would contribute to debulking, and the resectability of any areas of pelvic spread. An experienced gynecologic oncologist should be able to assess the extent of possible tumor removal and to decide which operative procedures would be most appropriate for cytoreduction.

In some cases, an omental tumor can be removed adequately by an infracolic omentectomy with division of the omental attachments to the transverse colon. If the tumor involves the gastrocolic omentum, the dissection will have to be carried upward to detach the omentum from the greater curvature of the stomach. Care must be taken to avoid injury to the mesentery of the transverse colon, to which the omentum is often adherent, and to the gastroepiploic vessels along the greater curvature of the stomach wall. Omental tumors often extend toward the spleen. An appropriately large incision usually allows resection of the tumor without the need for a splenectomy; however, a splenectomy is occasionally indicated. If the omental tumor infiltrates into the wall of the transverse colon, resection of the colon may be necessary to allow optimal debulking. Bulky tumor nodules on the diaphragm are often the limiting factor in achieving optimal cytoreduction, although to some extent they can be debulked sharply or with the use of the ultrasonic aspirator67 or argon beam coagulator.68 If resection of small areas of residual disease on the diaphragm will render the patient's disease optimal, small areas of the diaphragm can be resected with primary repair. It is usually necessary to mobilize the liver to perform this procedure. Although a chest tube may be required after resection of a portion of the diaphragm, one can often insert a catheter into the chest before tying the last stitch; with the end of the tube under water, the anesthesiologist can expel the air in the chest with a deep inspiration. Isolated nodules on the small intestine can be resected.

In the pelvis, bulky tumor often distorts or eliminates normal intraperitoneal tissue planes and anatomic landmarks. The retroperitoneal tissue planes, however, are usually well preserved and should be used as primary landmarks during the pelvic operation. The retroperitoneal space can usually be entered via incision of the peritoneum lateral to the infundibulopelvic ligament or the colon. After development of the space and direct identification of the ureter, the infundibulopelvic ligament can be ligated and transected. Continuing the retroperitoneal dissection, the uterine artery can also be ligated. After this is repeated contralaterally, mobilization of the ovarian tumors can proceed with less blood loss. In the case of a large tumor adherent to the pelvic sidewall, removal may require dissection of the ureter from the mass. If the tumor involves the lateral aspect of the uterus, one can perform the type of dissection used in a modified radical hysterectomy, unroofing the ureter as it passes through the parametrial tunnel and ligating the uterine vessels at this point. Extensive involvement of the rectosigmoid may require en bloc resection along with hysterectomy, as is performed in a posterior exenteration. Intestinal continuity can usually be reestablished by low anastomosis using intestinal stapling instruments. A colostomy is rarely indicated. Keeping in mind the observation first made by Griffiths that unless “optimal” cytoreduction can be accomplished the outcome is not improved, the surgeon should be reasonably certain that all bulky disease can be resected before undertaking an aggressive procedure.

Management of the pelvic and aortic lymph nodes in advanced ovarian cancer is not well defined. Although most patients with advanced ovarian cancer have involvement of pelvic or paraaortic nodes,69,70 most gynecologic oncologists agree that there is no need for routine diagnostic node sampling in patients with obvious intraperitoneal dissemination, because the information gained will have no bearing on treatment or prognosis. Whether an extensive lymphadenectomy has any effect on survival is unknown. One group has reported a retrospective series in which patients undergoing lymphadenectomy had an improved survival rate compared with historical controls.71 These data await confirmation. If the resection of bulky nodal disease allows optimal cytoreduction, it should be performed. It is our practice to remove enlarged lymph nodes in patients able to undergo optimal resection of intra-abdominal tumor.

The closure of the abdominal incision in advanced ovarian cancer patients deserves special attention. These patients are often elderly, obese, and nutritionally depleted, and they may have concomitant medical problems, such as diabetes, that interfere with wound healing and increase the risk of dehiscence. This closure may be performed with interrupted sutures or with a continuous suture using nonabsorbable or delayed absorbable material.72,73 Most studies show improved results with continuous mass closure techniques.

A number of centers have reported their experiences with the primary debulking of advanced ovarian cancer. Table 7 shows data from 11 reports,60,63,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81 published since 1979, on a total of 2282 patients. The great variation among these individual studies in the ability to achieve optimal cytoreduction (range: 17%–87%) must in part be explained by patient selection, varying degrees of surgical skill and aggressiveness, and different definitions of optimal cytoreduction. In general, skilled and experienced gynecologic oncologists should be able to accomplish optimal debulking in at least one-half of their patients with advanced ovarian cancer.

Table 7. Optimal Cytoreduction at Primary Surgery in Stage III And Stage

IV Ovarian Cancer

| Patients | Optimal Cytoreduction | |||

| First Author | Year | (N) | Number | Percentage |

| Smith | 1979 | 0792 | 190 | 24 |

| Delgado | 1984 | 0075 | 013 | 17 |

| Neijt | 1984 | 0186 | 076 | 41 |

| Wharton | 1984 | 0395 | 154 | 39 |

| Redman | 1986 | 0086 | 034 | 40 |

| Heintz | 1986 | 0070 | 049 | 70 |

| Neijt | 1987 | 0191 | 094 | 49 |

| Piver | 1988 | 0040 | 035 | 87 |

| Potter | 1991 | 0185 | 119 | 64 |

| Eisenkop | 1992 | 0126 | 103 | 82 |

| Baker | 1994 | 0136 | 113 | 83 |

| Total | 2282 | 980 | 43 | |

Although some authors have questioned the value of debulking surgery in patients with stage IV ovarian cancer, recent reports from several institutions, including Memorial Sloan-Kettering and the University of Pennsylvania,82,83,84,85 indicate a significant survival benefit to optimal cytoreduction in stage IV patients. Data from these studies are summarized in Table 8. These authors concluded that attempted cytoreduction was indicated in all patients with advanced ovarian cancer, even in patients with stage IV disease.

Table 8. Effect of Debulking on Survival in Stage IV Ovarian Cancer

| First Author | Year | Surgical Result | Patients(N) | Optimal (%) | Median Survival | P |

| Curtin | 1997 | Optimal (<2 cm) | 41 | 45 | 40 | .0100 |

| Suboptimal | 51 | 18 | ||||

| Liu | 1997 | Optimal (<2 cm) | 14 | 30 | 37 | .0200 |

| Suboptimal | 33 | 17 | ||||

| Munkarah | 1997 | Optimal (<2 cm) | 31 | 34 | 25 | .0200 |

| Suboptimal | 61 | 15 | ||||

| Bristow | 1998 | Optimal (<1 cm) | 25 | 30 | 38 | .0004 |

| Suboptimal | 59 | 10 |

The morbidity of aggressive cytoreductive surgery appears to be within acceptable limits, based on publications from major centers. Heintz and coworkers78 reported that with increasing experience, improved cardiovascular monitoring, and the increased use of parenteral hyperalimentation, the risk of serious perioperative morbidity decreased to 10%, the most commonly encountered problem in their series being postoperative pneumonia.

Although patients with small-volume residual tumor at the initiation of primary chemotherapy have an improved prognosis, these patients may have had smaller, less aggressive tumors to begin with. Their improved prognosis may relate more to the biology of the tumor than to the extent of the surgery. Several authors have attempted to address this issue by retrospective studies that examine the prognostic significance of the extent of disease before and after cytoreduction. In a report by Hacker and coworkers,86 patients with large-volume metastatic disease (greater than 10 cm) were analyzed according to the success of cytoreduction. Of the patients with bulky disease, those for whom tumor was reduced to optimal status had a longer median survival than those for whom it was not. However, patients who started with smaller volume disease and achieved optimal status had an even longer survival. In this series, published in 1983, Hacker and associates used only a single alkylating agent as the chemotherapy after surgery. In a 1988 series, Heintz and colleagues87 reported on the effect of preoperative tumor size in patients treated with cisplatin-based combination chemotherapy. They observed that optimal tumor resection in patients with large-volume metastatic disease improved median survival by approximately 12 months. Once again, the survival of patients with optimal cytoreduction (smallest residual disease) who started with large-volume disease was not as good as that for their counterparts who started with smaller volume disease.

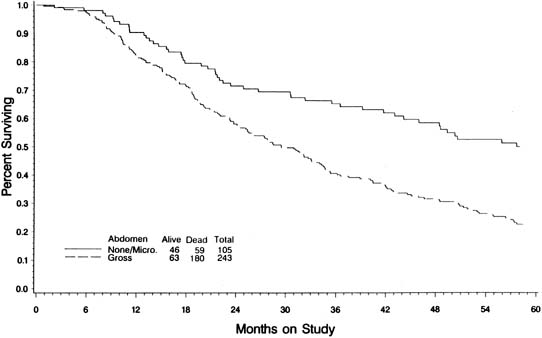

In an attempt to evaluate the relationship between cytoreductive surgery and tumor biology, Hoskins and colleagues88 reviewed 349 patients with stage III optimal (less than 1 cm) epithelial ovarian cancer. They divided patients into those found to have disease less than 1 cm in diameter on exploration and those who required cytoreductive surgery to achieve disease less than 1 cm. They theorized that if only surgery was important, survival would be equal between the two groups. They observed that patients found to have small-volume abdominal disease had a better survival than those who achieved small-volume residual disease via debulking (Fig. 4) (p = .0001). When evaluated by multivariate analysis, a variety of factors in addition to cytoreduction were found to be significant. The authors concluded that although cytoreduction was important, the biology of the tumor also influenced outcome. These studies suggest that although the finding of large-volume metastatic disease confers a poorer prognosis, and although the biology of the tumor is important, optimal tumor resection in these patients can improve median survival.

No prospective study randomizing ovarian cancer patients to aggressive cytoreduction versus less aggressive surgery has ever been performed, nor is such a study likely to be completed in the future. The GOG attempted such a trial with its protocol 80, but the trial came to a halt because of slow patient accrual; this failed attempt also was a reflection of the strong belief among gynecologic oncologists in the benefits of debulking.

One interesting concept that is emerging in gynecologic oncology is the possible use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, in which patients initially undergo chemotherapy and then interval surgical cytoreduction. Retrospective analyses have demonstrated equivalent overall survivals when comparing patients treated with primary chemotherapy followed by interval debulking with conventionally treated patients.89,90 One prospective, phase II, nonrandomized trial conducted by Kuhn and associates91 noted the median survival of 31 patients with stage IIIC ovarian cancer with large volume ascites treated with three cycles of primary chemotherapy before surgical debulking to be 42 months versus only 23 months for 32 patients treated with initial surgery followed by chemotherapy (p = .007). Although promising, until these results can be validated by a large prospective randomized study, initial surgical cytoreduction followed by adjuvant chemotherapy remains the gold standard of treatment.

Few procedures offer as great a challenge to the skill and judgment of the surgeon as the cytoreduction of advanced ovarian cancer. Because optimal cytoreduction is such an important part of treatment, we believe that patients with suspected advanced ovarian cancer should be referred to a center where trained and experienced gynecologic oncologists are available.