|

Our current understanding of human implantation has evolved from the

pioneering work of Hertig and colleagues 50 years ago, to the present

day receptor-mediated model with a more defined estimate of the endometrial

window of implantation as described recently by Yoshinaga and Wilcox,

respectively.16,17,18

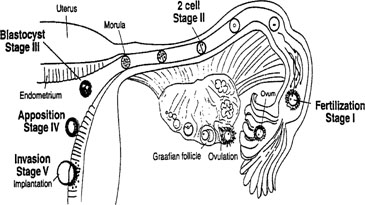

Based on work from the infertility and ART clinics, we now know that embryo

development is also critical before the overall window of receptivity

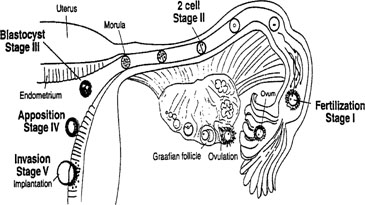

is achieved.19 The sequence of events from

the release of an ovum to the point of established pregnancy has been

divided into discreet stages of implantation. As shown in Figure

3, these stages consist of preimplantation events for both the embryo

and the endometrium, followed by apposition and attachment, and finally

penetration.

Fig. 3. Schematic showing the different stages of implantation (I-V). Stage I begins

with fertilization in the Fallopian tube. Transport through the

Fallopian tube and the first cell division marks stage II. At stage III, the

blastocyst enters the uterine cavity and with the onset of uterine

receptivity, adheres to the uterine lining (stage IV). Invasion of

the embryo into the endometrium signals the beginning of stage V. Fig. 3. Schematic showing the different stages of implantation (I-V). Stage I begins

with fertilization in the Fallopian tube. Transport through the

Fallopian tube and the first cell division marks stage II. At stage III, the

blastocyst enters the uterine cavity and with the onset of uterine

receptivity, adheres to the uterine lining (stage IV). Invasion of

the embryo into the endometrium signals the beginning of stage V.

|

Preimplantation Events of the Embryo

The earliest aspects of implantation in the human encompass the sequence

of events that lead from fertilization to blastocyst attachment and invasion.

After ovulation, the nascent oocyte is transported through the Fallopian

tube, where fertilization occurs, thus defining stage I of implantation.

Stage II is marked by the subsequent initiation of cell division in the

embryo. At stage III, the ball of embryonic cells, now called a morula,

enters the uterine cavity where further divisions results in formation

of the blastocyst. It is estimated that only 20% of human embryos

ever reach this point of development but for those that do, activation

of the genome begins that is essential for successful implantation.20,21

These initial events occur within a narrow time frame, as the embryo enters

the uterine cavity at 72 to 96 hours after fertilization.20,22

Once in the uterine cavity, the embryo remains free for roughly 3 days

before attaching to the endometrium.20 During

this time the embryo begins its communication with the mother even prior

to attachment to the endometrium. Maternal secretions likely nurture the

growing embryo.23,24,25

Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), produced by the embryo even before

hatching from the zona pellucida (ZP), is the pregnancy recognition signal

to the mother.26,27 The

ZP is important in prevention of polyspermy as well as providing an appropriate

environment for early embryonic development; ultimately the embryo must

hatch from the ZP prior to apposition, exposing surface receptors and

ligands that are important for attachment. The process of hatching becomes

less efficient with advancing maternal age and it is thought that zona

hardening can entrap an embryo within the ZP.28,29,30

Several methods of assisted hatching techniques have been suggested to

alleviate this problem in in vitro fertilization (IVF). Such methods

to weaken the ZP allows for zona shedding that has improved implantation

rates, in particular for older women or for prior implantation failures.

This progression of preimplantation events in the embryo is essential for

implantation, and occurs within a narrow time frame during the midsecretory

phase. As addressed in later sections, the endometrium is now

thought to become permissive to implantation during cycle days 20 to 24 of

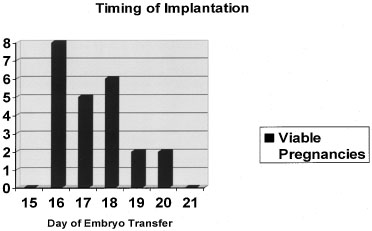

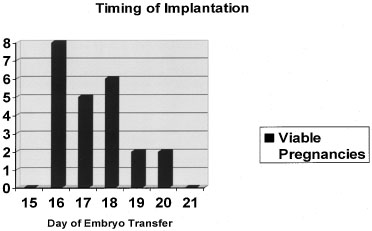

a normalized 28-day cycle, the so-called window of receptivity.18 Navot and colleagues31 demonstrated that pregnancies can be achieved by embryo transfers (ET) in

donor egg cycles on cycle days 15 to 20, with the vast majority of

success between days 16 and 19 (Fig. 4).31 Actual implantation takes place between embryonic days 5 and 6, so the

transfer of 2- to 3-day old embryos prior to day 20 yields peak implantation

rates.31 This concept was further expanded by this group by studying the timing

the first hCG detection in donor egg recipients.19 They found the average detection of pregnancy on embryonic day 7 with 2-day-old

embryos transferred on day 15 having hCG detection on day 20 and 2-day-old

embryos transferred on day 19 having hCG detection on days 24.19 No detection was found when embryos were transferred after day 19. These

data correlate well with a window of receptivity between cycle days 20 to 24 and

agree with the recent studies by Wilcox and colleagues18 who also studied the timing of implantation. Such donor-recipient models

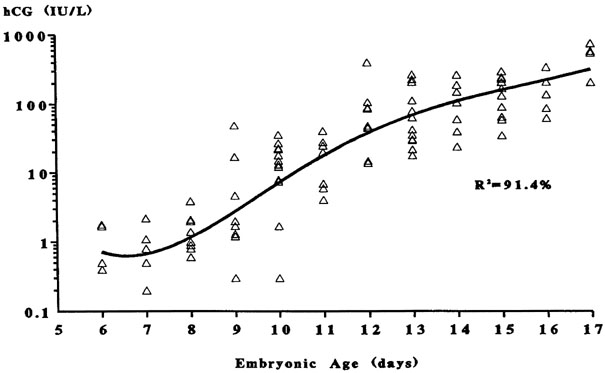

are able to establish the triphasic pattern of early hCG, rise which

has clinical applicability for many gynecologic problems such as ectopic

pregnancies, abnormal intrauterine pregnancies, and gestational trophoblastic

disease (Fig. 5).19  Fig. 4. Timing of implantation. Embryo transfers on cycle days 16 to 20 during

donor egg in vitro fertilization (IVF) cycles produced the greatest likelihood of a viable

pregnancy.(Navot D, Bergh PA, Williams M: An insight into early reproductive processes

through the in vivo model of ovum donation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 72:408, 1991.) Fig. 4. Timing of implantation. Embryo transfers on cycle days 16 to 20 during

donor egg in vitro fertilization (IVF) cycles produced the greatest likelihood of a viable

pregnancy.(Navot D, Bergh PA, Williams M: An insight into early reproductive processes

through the in vivo model of ovum donation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 72:408, 1991.)

|

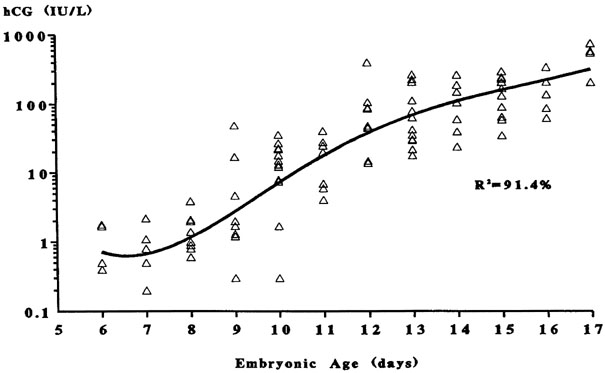

Fig. 5. The triphasic pattern of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) rise. Note

the faster rise of hCG prior to the anticipated first missed menstrual

period than after the missed period(Bergh PA, Navot D: The impact of embryonic development and endometrial

maturity on the timing of implantation. Fertil Steril 58:532, 1992.) Fig. 5. The triphasic pattern of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) rise. Note

the faster rise of hCG prior to the anticipated first missed menstrual

period than after the missed period(Bergh PA, Navot D: The impact of embryonic development and endometrial

maturity on the timing of implantation. Fertil Steril 58:532, 1992.)

|

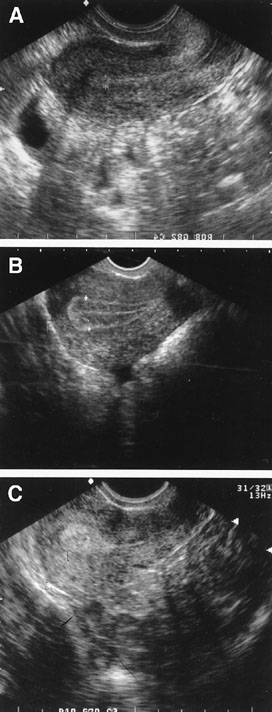

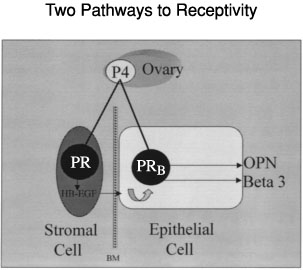

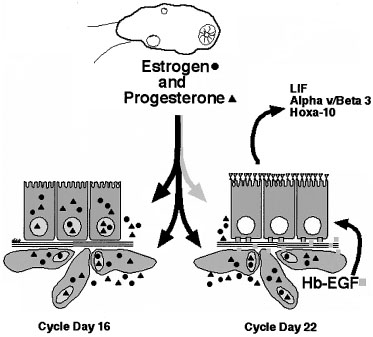

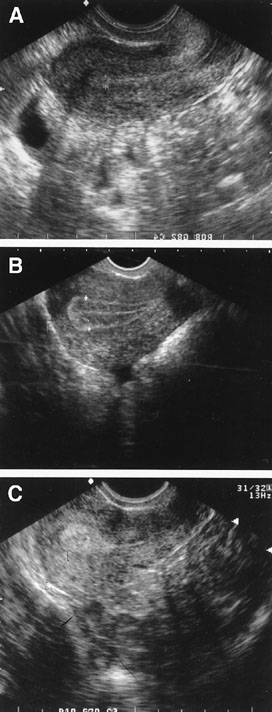

Preimplantation Events of the Uterus STRUCTURAL CHANGES OF THE ENDOMETRIUM.

During the first half of the menstrual cycle, called the proliferative

phase, the endometrium thickens in response to rising estradiol levels

(Fig. 6). As assessed

by transvaginal ultrasound, the endometrium grows rapidly during the first

14 days of the cycle. It is thought that an endometrial thickness less

than 6 mm is unlikely to support a pregnancy.32,33

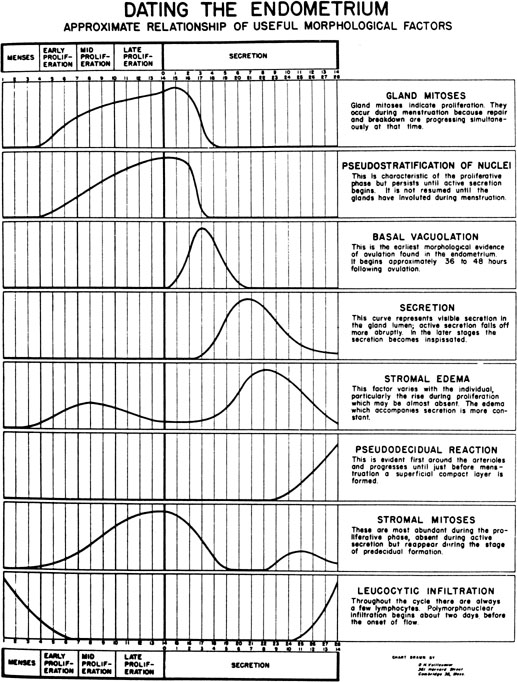

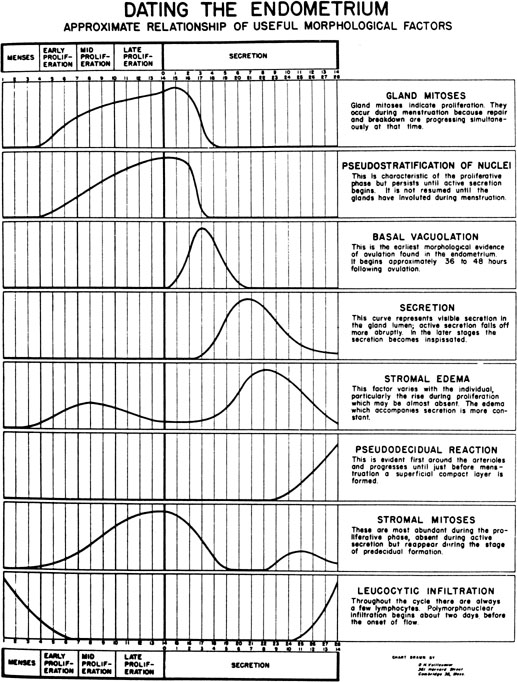

Once ovulation takes place and the granulosa transforms into the corpus

luteum (CL), the endometrium is converted to a secretory structure under

the influence of rising progesterone. This conversion follows an orderly

progression as demonstrated by Noyes and coworkers34

in their now classic paper on endometrial dating (Fig.

7). Initially, the endometrial glandular epithelium begins to synthesize

and secrete glycogen and glycoproteins, and by midcycle, stromal edema

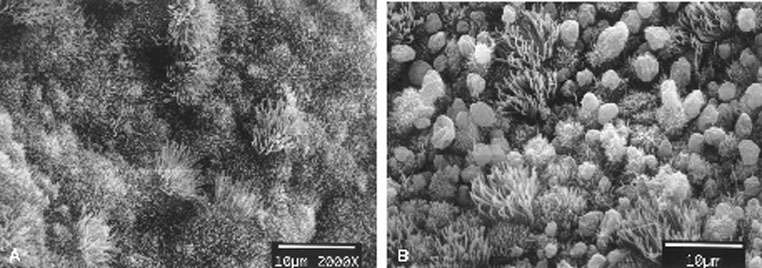

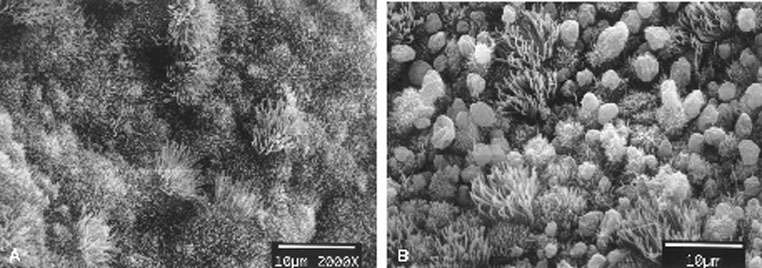

develops, accompanied by proliferation of the spiral arterioles. Ultrastructurally,

scanning electron microscopy of the midluteal luminal epithelium shows

the development of small protrusions called pinopods, the appearance of

which coincides well with the suspected time of maximal receptivity (Fig.

8). Such surface modifications are thought to play a functional role

in embryo apposition and attachment.35,36,37

Fig. 6. Endometrial echogenic patterns reflective of the hormonally-induced progression

throughout a normal menstrual cycle. Panel A shows early proliferative endometrium. Panel B shows the trilaminar late proliferative endometrium. Panel C shows the echogenic secretory endometrium. Fig. 6. Endometrial echogenic patterns reflective of the hormonally-induced progression

throughout a normal menstrual cycle. Panel A shows early proliferative endometrium. Panel B shows the trilaminar late proliferative endometrium. Panel C shows the echogenic secretory endometrium.

|

Fig. 7. The dating criteria of Noyes and colleagues used to assess the maturation

of the endometrium.(Noyes RW, Hertig AT, Rock J: Dating the endometrial biopsy. Fertil Steril 1:3, 1950.) Fig. 7. The dating criteria of Noyes and colleagues used to assess the maturation

of the endometrium.(Noyes RW, Hertig AT, Rock J: Dating the endometrial biopsy. Fertil Steril 1:3, 1950.)

|

Fig. 8. Scanning electron micrographs of endometrium on luteinizing hormone (LH) surge

day +2 (A) and +8 (B). Note the development of balloon-like protrusions called pinopods. Fig. 8. Scanning electron micrographs of endometrium on luteinizing hormone (LH) surge

day +2 (A) and +8 (B). Note the development of balloon-like protrusions called pinopods.

|

Another progesterone-related uterine change is the frequency of uterine

contractions. Animal studies have shown decreased implantation rates with

increasing uterine contraction.38,39

Recent work by Fanchin and coworkers40 using

digitized 5-minute ultrasound scans showed that contractility is inversely

related to progesterone levels in humans as well. They also showed decreased

clinical pregnancy rates with increasing uterine contractions. Lesny and

coworkers41 also studied this phenomenon

doing mock ET using 30 μL of an echogenic fluid medium. They noted

that with easy transfers, uterine contractions remained at a stable baseline

and the medium did not migrate significantly. However, difficult transfers

were associated with strong, random contractions and the fluid medium

migrated from the fundal region in six of seven patients (in two the medium

migrated to the Fallopian tubes).41 This

is still a relatively new concept but may lead to future theraputic considerations

in ART.

BIOCHEMICAL CHANGES OF THE ENDOMETRIUM. Aside from what is known about the structural changes that the endometrium

undergoes during the secretory phase, there is also a growing body

of information regarding the biochemical changes of the endometrium. Discoveries

regarding the ECM, cell adhesion molecules, cytokines and

growth factors, and the enzymes that degrade the ECM have shed light on

embryo-endometrial interactions that occur during attachment and invasion. Extracellular Matrix.

The ECM is formed from secreted proteins and glycoproteins and forms

the ground substance outside the cells in all tissues. The ECM appears

to play an important role in the cell-cell interactions.42

Analysis of these substances in the endometrium throughout the menstrual

cycle has shown constitutive expression of collagen types III and V and

fibronectin.42 Cycle-dependent variations

in expression also exist; type VI collagen is produced throughout the

proliferative phase, but declines during the secretory phase. There may

also be differences in the expression of these various ECM components

in endometrium of fertile and infertile women.43

The luminal surface is an effective barrier to implantation during much

of the reproductive cycle.39 Early on, it

was noticed that there is thinning of the carbohydrate-rich domain of

the luminal uterine surface, known as the glycocalyx, and a decreased

negative charge at the luminal epithelium at the midluteal phase.44,45

Variations in the ECM that make up these phenomena may hinder embryo-epithelial

contact necessary for apposition. One mucin component in particular, MUC-1,

may serve as an antiadhesive molecule and limit apposition.46

In rodents, MUC-1 disappears at the time of implantation and persistent

expression results in implantation failure. Studies in human endometrium

have been less convincing because MUC-1 persists throughout the luteal

phase in women. Nevertheless, there may still be a role of MUC-1 during

human implantation.47

Matrix Metalloproteinases and Their Inhibitors.

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are zinc-containing endopeptidases that

enzymatically digest certain ECM proteins and therefore play an important

role in tissue remodeling processes.48,49

There are at least three groups of these enzymes differentiated by their

substrates, as well as a group of membrane-type matrix metalloproteinases

(MT-MMPs) (Table 1). Endometrial expression of MMPs

is highly regulated to facilitate successful implantation or timely degradation

and remodeling of the endometrial lining during menstruation, in the absence

of a successful pregnancy.50,51

TABLE 1. Matrix Metalloproteinases

Class | Name | Substrate | Cell Source |

Collagenases | MMP-1 | Collagen I, II, III, VII, VIII, and X | Endometrial stroma, Cytotrophoblast |

| | MMP-8 | Same as MMP-1 | Same as MMP-1 |

Gelatinases | MMP-2 (gelatinase A) | Collagen IV gelatin | Endometrial stroma, Cytotrophoblast |

| | MMP-9 (gelatinase B) | Same as MMP-2 | Same as MMP-2 |

Stromelysin | MMP-3 (stromolysin-1) | Fibronectins, laminins, Collagens III, IV, V, elastin, proteoglycan | Endometrial stroma |

| | MMP-10 (stromolysin-2) | Same as MMP-3 | Same as MMP-3 |

| | MMP-11 (stromolysin-3) | ? | Endometrial epithelium |

| | MMP-7 (matrilysin) | Collagen IV, gelatin, fibronectin, proteoglycan | Proliferative endometrial epithelium |

Membrane-type | MT-MMP-1 | ? | |

MMPs | MT-MMP-2 | | |

| | MT-MMP-3 | | |

MMP, matrix metalloproteinases.

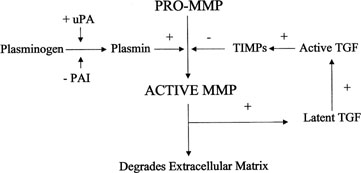

MMPs are produced as inactive precursors that require activation by other

peptidases, denaturants, or heat.52 This

cascade of activation is often initiated by the MT-MMPs and is tightly

controlled by a variety of tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs).53

The ECM constituents can actually regulate cellular activity through a

receptor-mediated process, thus, production and breakdown of the ECM influences

a tissue’s characteristics through a dynamic reciprocity and is

vital to invasion and maternal recognition of a pregnancy.50,54

There are also other interactions between the MMPs and the embryo-endometrial

complex that are likely involved with implantation. Cell adhesion receptors

known as integrins appear to have a role in MMP expression and function.

Engagement of a placental integrin with fibronectin induces MMP expression

and the integrin αvβ3 directly binds to and activates MMP-2.55,56

MMP-2 is one of the most active MMPs in the distal invasive cell column

of human trophoblasts during implantation and allows these cells to invade

in the direction of their migration.57 MMP-9

is also essential for both rodent and human placental invasion.58

Decidual cells strongly express the MMP inhibitor TIMP-2, presumably as

part of the maternal mechanism to block uncontrolled invasion of the placenta.59

The delicate interplay between these factors must be precisely coordinated

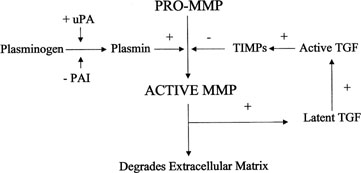

for successful but controlled invasion of the trophoblast. Plasminogen,

its activators, and its inhibitors appear to participate in this process.60

Plasmin, a protease derived from plasminogen, activates certain MMPs and

has a role in degradation of the ECM. Regulation of plasminogen to plasmin

conversion is stimulated by urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA)

and inhibited by alpha2-macroglobulin (α2MG). Human

endometrium, embryos, and trophoblasts express both uPA, and its receptor

and mutations in these have been associated with implantation failure.61,62,63,64,65

Activity of plasminogen activator (PA) is tightly regulated by specific

inhibitors of PAs (PAI-1 and PAI-2), which bind and inactivate PAs.66

Plasmin activates transforming growth factor β (TGF-β),

which in turn activates TIMP and PAI production, thus inhibiting further

plasmin activation (Fig.

9). Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is associated with elevated PAI-1

activity, which may contribute to the higher than expected rate of pregnancy

loss via this pathway.67,68

Fig. 9. Activation of matrix metalloproteinases (MMP). MMPs are derived from a

precursor promolecule that is cleaved by plasmin to form active MMP. This

process is inhibited by tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs). uPa, urokinase-type

plasminogen activator; PAI, plasminogen activator

inhibitor. Fig. 9. Activation of matrix metalloproteinases (MMP). MMPs are derived from a

precursor promolecule that is cleaved by plasmin to form active MMP. This

process is inhibited by tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs). uPa, urokinase-type

plasminogen activator; PAI, plasminogen activator

inhibitor.

|

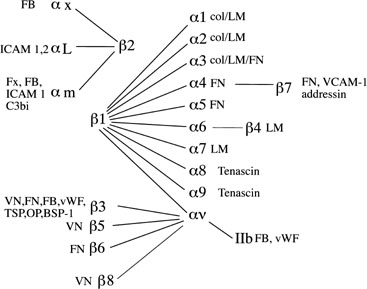

Integrin Cell Adhesion Molecules.

Integrins, one member of a larger family of cell adhesion molecules,

have been well studied at the levels of the embryo, trophoblast, and endometrial

epithelium and stroma throughout the menstrual cycle and into pregnancy

(Fig. 10).69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76

While many integrins are constitutively expressed in human endometrium,

the expression of certain integrins coincides well with the period of

peak uterine receptivity.71,72

The timing of receptivity was first described in the classic studies by

Hertig and colleagues.16 Over a 15-year

time period, they examined 210 hysterectomy specimens, ranging from the

day of ovulation to 17 days postovulation. They observed that in uteri

obtained prior to cycle day 20, all embryos were free-floating in the

tubes or uterus, while in uteri obtained after day 21 the embryos were

attached to the uterine lining. Many subsequent studies have helped establish

that peak uterine receptivity is between cycle days 20 and 24 of a normalized

28-day cycle.18,31

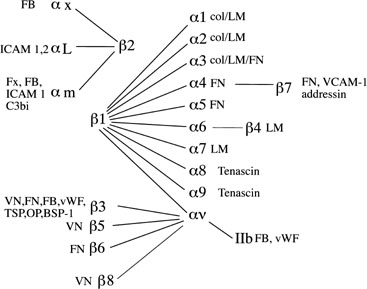

Fig. 10. Integrin subunits. The spider-gram displays the various associations between α and β integrin subunits. FB, fibrinogen; ICAM, intracellular

adhesion molecule; FN, fibronectin; Fx, factors; vWF, von

Willebrand’s factor; TSP, thrombospondin; OP, osteopontin; BSP, bone

sialoprotein; VCAM-1, vascular adhesion molecule-1; LM, laminin. Fig. 10. Integrin subunits. The spider-gram displays the various associations between α and β integrin subunits. FB, fibrinogen; ICAM, intracellular

adhesion molecule; FN, fibronectin; Fx, factors; vWF, von

Willebrand’s factor; TSP, thrombospondin; OP, osteopontin; BSP, bone

sialoprotein; VCAM-1, vascular adhesion molecule-1; LM, laminin.

|

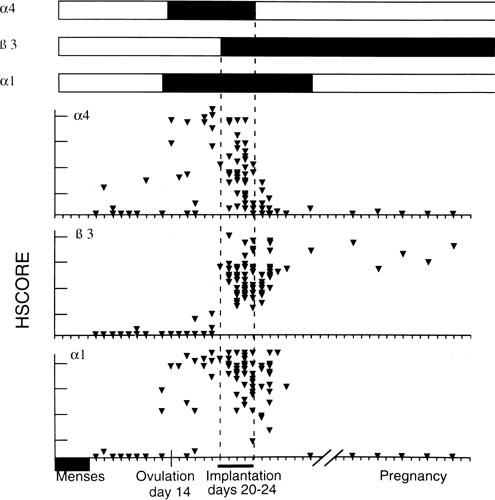

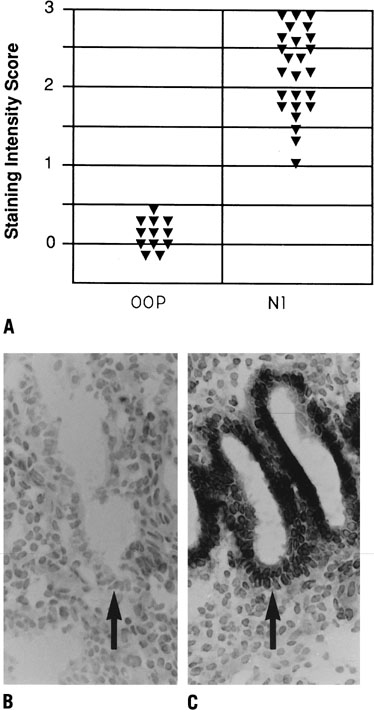

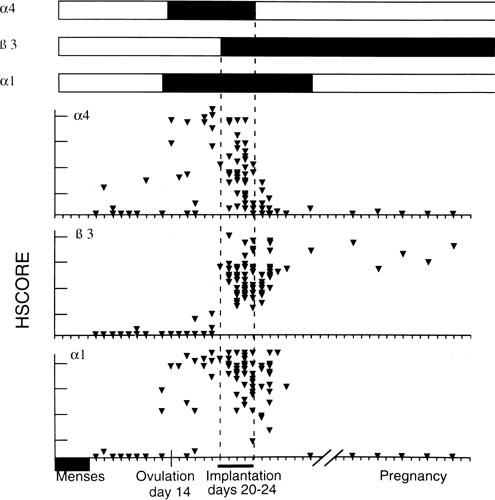

Three integrins (α1β1, α4β1, and αvβ3)

have been shown to be coexpressed during the window of receptivity in

humans, present together from cycle day 20 to 24 (Fig.

11). Of these three, the luminal epithelium expresseses only αvβ3

at the apical pole, suggesting a potential role in embryo attachment.77

This integrin recognizes the three amino acid sequence arg-gly-asp (RDG),

which has been implicated in trophoblast attachment and outgrowth in several

studies.78,79 Interestingly,

we have shown a loss of midluteal αvβ3 expression in certain

women with unexplained infertility as well as in women with conditions

known to have diminished implantation rates, including PCOS, endometriosis,

and those with tubal disease and hydrosalpinges, further implicating the

critical role of this integrin during implantation.74,75,76,80

Animal studies have also demonstrated that blockade of this integrin will

prevent or reduce implantation. This could prove to be useful for future

diagnostic and theraputic considerations for the infertile couple.

Fig. 11. Relative intensity of staining for the epithelial α4,β3 and α1 integrin

subunits throughout the menstrual cycle and in early

pregnancy. Inmmunohistochemical staining was assessed by a blinded

observer using the semiquantitative HSCORE (ranging from 0 to 4) and

correlated to the estimate of histologic dating based on pathologic criteria

or by last menstrual period (LMP) in patients undergoing therapeutic

pregnancy termination. The negative staining (open bars) was shown

for immunostaining of an HSCORE 0.7, for each of the three integrin

subunits. Positive staining for all three integrin subunits was seen

only during a 4-day interval corresponding to cycle day 20 to 24, based

on histologic dating criteria of Noyes and colleagues.28 This interval of integrin coexpression corresponds to the putative window

of implantation. Of the three, only the αvβ3 integrin

was seen in the epithelium of pregnant endometrium.(Lessey BA, Castelbaum AJ, Buck CA, et al: Further characterization of

endometrial integrin during the menstrual cycle and in pregnancy. Fertil

Steril 62:497, 1994.) Fig. 11. Relative intensity of staining for the epithelial α4,β3 and α1 integrin

subunits throughout the menstrual cycle and in early

pregnancy. Inmmunohistochemical staining was assessed by a blinded

observer using the semiquantitative HSCORE (ranging from 0 to 4) and

correlated to the estimate of histologic dating based on pathologic criteria

or by last menstrual period (LMP) in patients undergoing therapeutic

pregnancy termination. The negative staining (open bars) was shown

for immunostaining of an HSCORE 0.7, for each of the three integrin

subunits. Positive staining for all three integrin subunits was seen

only during a 4-day interval corresponding to cycle day 20 to 24, based

on histologic dating criteria of Noyes and colleagues.28 This interval of integrin coexpression corresponds to the putative window

of implantation. Of the three, only the αvβ3 integrin

was seen in the epithelium of pregnant endometrium.(Lessey BA, Castelbaum AJ, Buck CA, et al: Further characterization of

endometrial integrin during the menstrual cycle and in pregnancy. Fertil

Steril 62:497, 1994.)

|

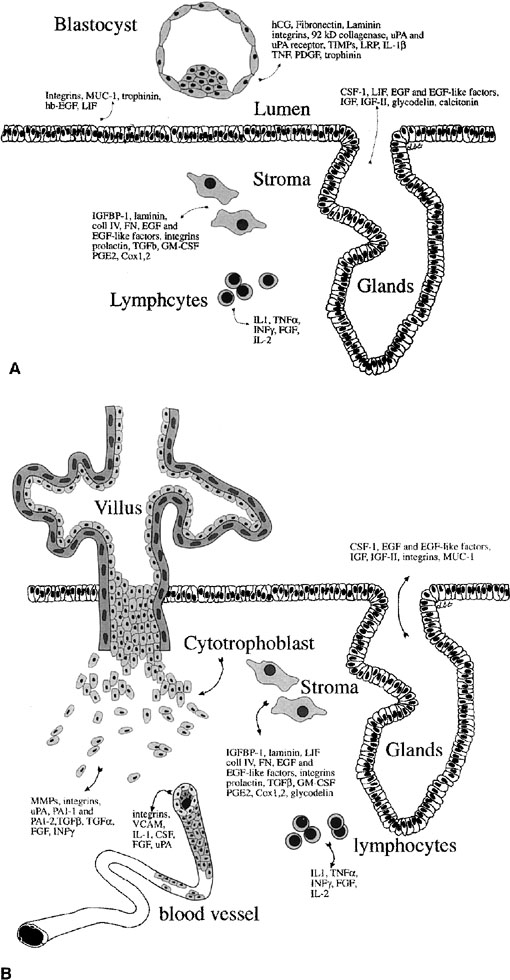

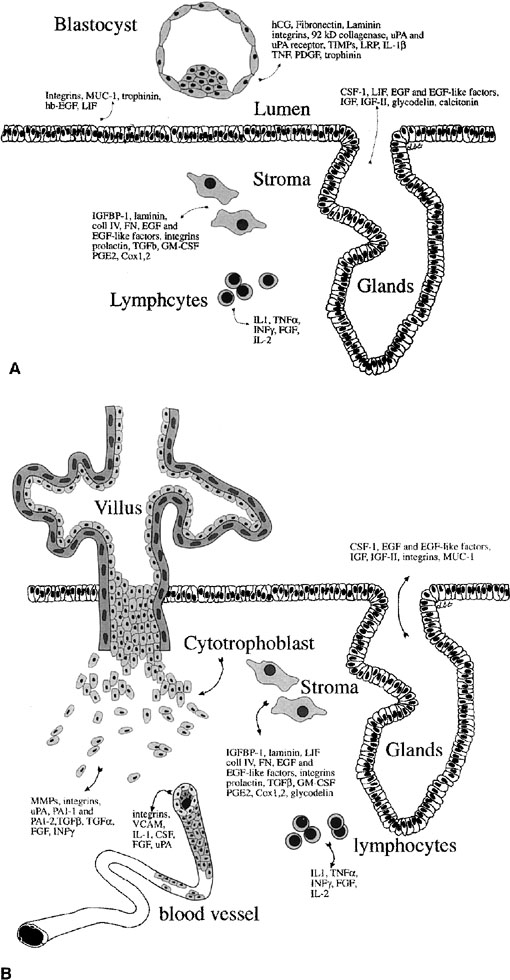

Other Markers of Uterine Receptivity.

A growing number of proteins involved in endometrial-embryo interaction

both during and after implantation have been identified (Fig.

12).81 As mentioned earlier, mucins

like MUC-1 have been suggested as markers of receptivity. Glycodelin (placental

protein 14 [PP14]) is a gylcoprotein produced by the glandular epithelium

and has been associated with inadequate hormonal cycles.82

There are also other adhesion molecules that undergo upregulation during

the time of uterine receptivity, such as trophinin, cadherin-11,83,84

and the hyaluronate receptor, CD44.85 Many

cytokines and growth factors, such as leukemia-inhibitory factor (LIF),

insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-II, heparin-binding epidermal growth

factor (HB-EGF), and interleukin (IL)-1β also appear to be expressed

during peak uterine receptivity.86,87,88,89

|

Fig. 12. Embryo-endometrial dialogue. A.

Illustration of a number of factors produced by the embryo and endometrium

before apposition. B. Factors produced by the trophoblasts

and endometrium after invasion. hCG, human chorionic gonadotropin;

uPA, urokinase-type plasminogen activator; TIMPs, tissue inhibitors

of matrix metalloproteinases; LRP, lipoprotein receptor–related

protein; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; TNF, tumor necrosis

factor; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor; CSF-1, colony-stimulating

factor-1; LIF, leukemia-inhibitory factor; EGF, epidermal growth

factor; IGF, insulin-like growth factor; IGFBP-1, insulin-like growth

factor binding product-1; coll IV, collagen IV; FN, fibronectin;

TGF-β, transforming growth factor β; GM-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage

colony stimulating factor; PGE2, prostaglandin E2; TNF-α,

tumor necrosis factor α; IFN-γ, interferon-γ;

FGF, fibroblast growth factor; MMPs, matrix metalloproteinaese.

Fig. 12. Embryo-endometrial dialogue. A.

Illustration of a number of factors produced by the embryo and endometrium

before apposition. B. Factors produced by the trophoblasts

and endometrium after invasion. hCG, human chorionic gonadotropin;

uPA, urokinase-type plasminogen activator; TIMPs, tissue inhibitors

of matrix metalloproteinases; LRP, lipoprotein receptor–related

protein; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; TNF, tumor necrosis

factor; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor; CSF-1, colony-stimulating

factor-1; LIF, leukemia-inhibitory factor; EGF, epidermal growth

factor; IGF, insulin-like growth factor; IGFBP-1, insulin-like growth

factor binding product-1; coll IV, collagen IV; FN, fibronectin;

TGF-β, transforming growth factor β; GM-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage

colony stimulating factor; PGE2, prostaglandin E2; TNF-α,

tumor necrosis factor α; IFN-γ, interferon-γ;

FGF, fibroblast growth factor; MMPs, matrix metalloproteinaese.

|

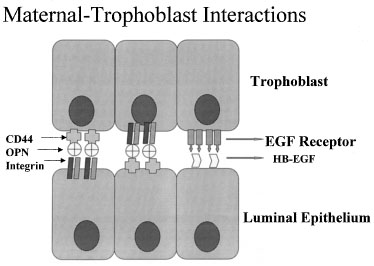

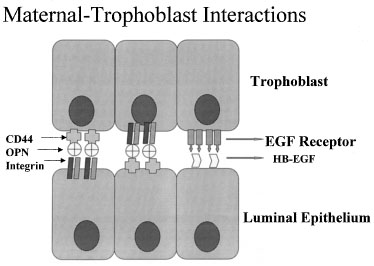

One of the most recently defined markers is a secreted glycoprotein called

osteopontin (OPN). This RGD-containing protein has binding sites to two

major receptors that are present on both the material and embryonic epithelium,

αvβ3 and CD44. Osteopontin is a 70-kd glycosylated phosphoprotein

secreted by the glandular epithelium and is expressed during the midsecretory

phase, localized to the luminal endometrial epithelium.90

Regulation of OPN is tied to progesterone.90,91,92

The apical localization of OPN suggests a role as a sandwich ligand that

serves as a bridge binding surface receptors on the endometrial and embryonal

surfaces (Fig. 13).

Fig. 13. Schematic drawing of apposition. Embryos and endometrial cells express

integrins and CD44, both of which bind osteopontin (OPN). This allows

apposition through a sandwich-like binding mechanism. EGF, epidermal growth

factor; HB-EGF, heparin-binding epidermal growth factor. Fig. 13. Schematic drawing of apposition. Embryos and endometrial cells express

integrins and CD44, both of which bind osteopontin (OPN). This allows

apposition through a sandwich-like binding mechanism. EGF, epidermal growth

factor; HB-EGF, heparin-binding epidermal growth factor.

|

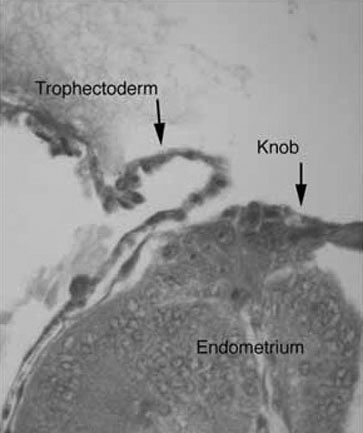

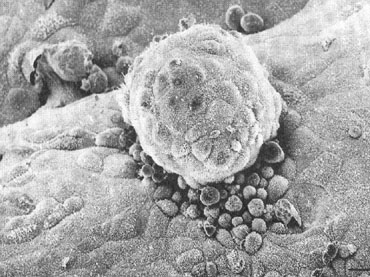

Apposition

Despite this wide array of structural and biochemical changes by the

preimplantation embryo and endometrium, it has been difficult to ascribe

specific function to many of them. Apposition, defined as stage IV of

implantation, is still an elusive process to observe in humans, and there

remains much uncertainty about its mechanism and exact timing. It appears

many of the factors described above have critical roles in bringing the

endometrium and embryo together. Both express a variety of adhesion molecules

and ligands during the expected time of implantation. Current theories

suggest that endometrial surface projections, known as pinopods, form

a privileged site of receptor expression, raising the endometrial apical

surface above anti-adhesive molecules such as MUC-1. Once contact is made

between the embryo and the maternal surface, polar trophoblast displaces

the endometrial cells by sending ectoplasmic protrusions between them

and disrupting their desmosomes.93,94

This invasiveness appears dependent on the formation of the syncitiotrophoblast,

occuring less than 24 hours after embryo adhesion.95

Penetration and Invasion

Apposition is followed quickly by epithelial penetration and invasion

(stage V). Again, this is a process that is not clearly understood but

must be tightly orchestrated by a multitude of components previously mentioned,

namely the ECM, cell adhesion molecules, MMPs and their inhibitors, and

a variety of growth factors and their receptors. The importance of the

ECM on cell surface proteolysis has been studied and suggests that on

invasion, cell migration and the acquisition of an invasive phenotype

may be stimulated by exposed ECM and digested fragments of the endometrial

or trophoblast ECM mediated in large part by activation of specific MMPs.96,97

Rather than a destructive process, invasion of the placental cells appears

to involve breaking the intercellular connections and by selective apoptosis.

The intruding trophoblast appears to adhere to the lateral surfaces of

the luminal epithelium with formation of junctional complexes and pushes

these cells aside as the mass of the embryo migrates into the underlying

decidua.

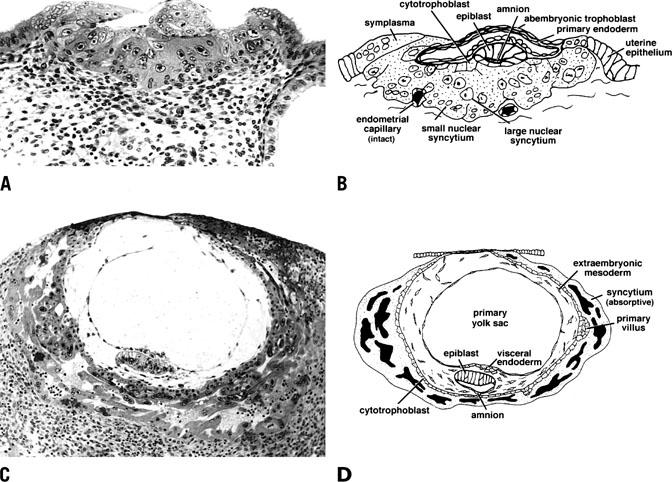

With time, trophoblast invasion reaches the maternal circulation. Access

to the maternal vasculature becomes a priority for the growing embryo, which

requires increasing quantities of nutrients and oxygen and better

management of cellular waste for its survival. This stage of implantation

is marked by rapid expansion of both cytotrophoblast and synctial

trophoblast (Fig. 14).98 At stage Va of invasion, the maternal vasculature remains intact, but

becomes surrounded by the expanding syncytium. With further growth, the

syncytium and cytotrophoblast invade the maternal vasculature, and the

cytotrophoblast is incorporated into the wall of maternal vessels. As

detailed later, this ability to mimic endothelial cell characteristics

is critical to this invasion, thus establishing a blood supply and

a presence within the maternal tissues that will remain intact for the

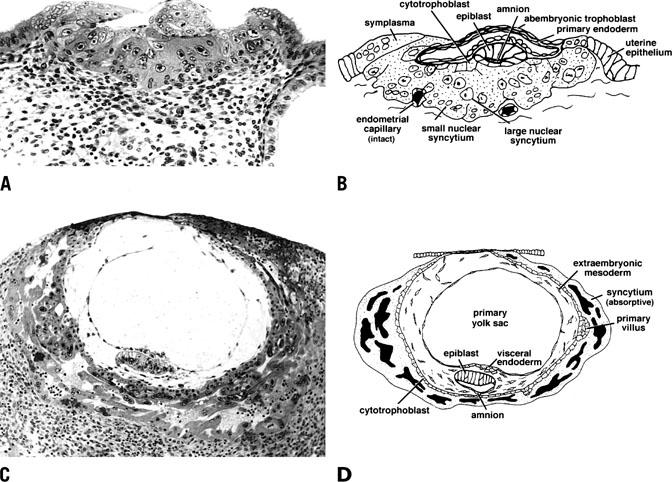

remainder of the pregnancy.  Fig. 14. Photomicrograph (A) and schematic drawing (B) of a human implantation site during early implantation (stage Va). At

this stage the maternal vasculature remains intact, but becomes surrounded

by the expanding syncytium. By stage Vc (C and D), the embryo is fully below the luminal surface. A layer of cytotrophoblast

that will soon bud to form villi surrounds the embryo, and lacunae

have formed as a result of maternal vascular invasion. Development

of the placenta and stage V ends approximately 11 to 12 days after ovulation

with the development of primary villi.(Dr. Allen Enders, University of California Davis.). Fig. 14. Photomicrograph (A) and schematic drawing (B) of a human implantation site during early implantation (stage Va). At

this stage the maternal vasculature remains intact, but becomes surrounded

by the expanding syncytium. By stage Vc (C and D), the embryo is fully below the luminal surface. A layer of cytotrophoblast

that will soon bud to form villi surrounds the embryo, and lacunae

have formed as a result of maternal vascular invasion. Development

of the placenta and stage V ends approximately 11 to 12 days after ovulation

with the development of primary villi.(Dr. Allen Enders, University of California Davis.).

|

As shown in Figure 8C and 8D, stage Vb of invasion is characterized by expansion of the syncytium

and cytotrophoblast and establishment of lacunae as a result of

vasculature invasion. By stage Vc, the embryo is now fully below the

luminal surface and the circumference of the embryo is surrounded by a

layer of cytotrophoblast that will rapidly bud to form villi. Development

of the placenta and stage V ends by day 11 to 12 after ovulation

with the development of primary villi. |