Unlike autosomes, the Y chromosome is unique in that it has no homologue. Recombination

in this chromosome is restricted to a small telomeric

pseudoautosomal region, which homologously pairs with the X chromosome

during male meiosis. The remainder of the Y is thus nonrecombining and

represents approximately 95% of its length (Fig. 2).  Fig. 2. Diagram of human Y chromosome euchromatic, heterochromatic, and pseudoautosomal (PAR) regions. Deletion intervals 1 through 6 are noted, as are SRY (the testis determining factor), ZFY, and HYA. Regions associated with azoospermia (or severe oligospermia) are designated

AZFa (green), AZFb (red), and AZFc (blue). Fig. 2. Diagram of human Y chromosome euchromatic, heterochromatic, and pseudoautosomal (PAR) regions. Deletion intervals 1 through 6 are noted, as are SRY (the testis determining factor), ZFY, and HYA. Regions associated with azoospermia (or severe oligospermia) are designated

AZFa (green), AZFb (red), and AZFc (blue).

|

All aspects of the mammalian male phenotype, including spermatogenesis, are

either directly or indirectly due to the activity of the Y chromosome. The

central role played by the mammalian Y chromosome in sex determination

was first described in 1959, with the report that XO patients

were female and XXY patients were male.10,11 This indicated that in mammals (unlike in Drosophila, whose sex is determined by X:autosome ratio), a dominant Y chromosome-located

gene(s) was the primary testis determinant, termed TDY (testis determining Y). TDY initiates primary sex determination by inducing an indifferent gonad to

form a testis. This testicular environment, in turn, initiates secondary

sexual differentiation, causing the early germ cells to follow the

male pathway by forming prospermatogonia, rather than meiotic oocytes. Thus, a

functional TDY is an absolute requirement for male fertility.12 The localization and eventual cloning of TDY was made possible by deletion mapping of the Y using XX male and XY female

patients.13,14,15 These individuals result from rare, illegitimate pairing of the pseuodoautosomal

region of the Y with the X chromosome which leads to translocation

of a small, variable portion of the Y chromosome onto the X and

a corresponding loss of a portion from the Y. If this portion involves TDY then XX(Y+) sex-reversed males and XY(del) infertile females are produced. XX(Y+) persons are phenotypically male but sterile because of the presence of

two X chromosomes, which invariably leads to profound defects in the

mitotic stages of spermatogenesis. Identification of the specific gene

responsible for testis determination proved difficult, with a number

of candidates proposed and subsequently rejected before the true gene

was found. The first gene associated with the Y chromosome was the male-specific

minor histocompatibility antigen gene H-Y.16,17,18,19 Because it was the only locus known to map to the Y, it became an excellent

candidate for TDY until deletion mapping unequivocally assigned it to an area outside of

that responsible for testis determination.20,21,22 The first convincing TDY candidate gene was ZFY (Zinc finger protein on the Y), identified by Page and colleagues23 in 1987. As additional XX(Y+) males were identified with very small Y translocations that did not include ZFY, it became apparent that this gene could not be the testis-determining

factor gene (TDF).24 In a collaborative European study, a careful examination of XX male patients

with critical Y translocations led Goodfellow and Fellous to isolate

a gene they named SRY and to show that it was the elusive TDF gene (see Fig. 2).25,26 Prima facie evidence that SRY was necessary and sufficient for primary testis determination was provided

by constructing an XX Sry transgenic mouse. These mice developed as phenotypically sterile males, reiterating

the human XX male syndrome.27 Deletion mapping of the Y chromosome has also provided valuable evidence

about other biological functions of the Y chromosome, namely those involved

in the control of spermatogenesis. In 1976, Tiepolo and Zuffardi28 identified four azoospermic patients with large cytologically visible

de novo deletions of the distal half of Yq. They postulated that this

region of the Y chromosome contained genes essential for spermatogenesis

and designated this locus the azoospermic factor (AZF) region. Specific regions responsible for spermatogenesis have been ascribed

to the Y chromosome of other organisms, suggesting that this is

an evolutionarily conserved function.29,30 More refined mapping of AZF (and other regions of the Y chromosome) has been greatly facilitated by

the generation of a large number of Y-specific sequence-tagged sites (STS). An

STS is a short stretch of known genomic sequence defined by

the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with specific primers. STSs were

used to map specific AZF loci on the Y chromosome based on deletions observed in infertile men.31,32 Extensive analysis for the presence of 76 Yq-specific STSs in males with

idiopathic azoospermia or severe oligospermia has suggested that there

are three distinct regions in Yq, termed AZFa (proximal), AZFb (central), and

AZFc (distal) associated with this phenotype (see Fig. 2).33 Much of the Y chromosome is occupied by repeated sequences of unknown function. This

has led many to believe that the Y was a repository of degenerating

sequences with little biological importance and few real genes. Systematic

examination of the Y chromosome, however, has revealed

that there are more genes than had previously been appreciated and that

these genes may play critical roles in the regulation of normal testicular

function. Recent efforts have focused on the isolation of such

specific genes from all three AZF regions. An AZF candidate was first proposed in 1993 with the description of a novel

multicopy gene family designated YRRM (Y chromosome RNA recognition motif).34 YRRM (since renamed RBM) is a highly conserved family of Y-specific genes that belong to a superfamily

of RNA-binding proteins. RBM is expressed in the nuclei of male germ cells; its germ cell-specific

expression suggests that regulation of RNA metabolism may be important

for the proper control of spermatogenesis. A member of this gene family

mapping to interval 6 was deleted in several infertile patients. However, because RBM is a multigene family, specific roles for individual family members must

be correlated with the azoospermic phenotype; as yet, no definitive

proof for its being AZF has been reported. In a study by Reijo and associates,35 13% of subjects with nonobstructed azoospermia carried de novo deletions

in the 6D-6E interval of the Y chromosome; deletions in this area were

also seen in severely oligospermic men. No members of the RBM family were detected in this area, but a new AZF candidate, designated DAZ (deleted in azoospermia) was proposed. Initially thought to be a single-copy

gene, DAZ was deleted in a high percentage of the azoospermic population tested

by the authors. It, too, bears an RNA recognition motif, but it is expressed

in the cytoplasm of premeiotic testicular germ cells, making it

an excellent candidate for a factor that might be important in the maintenance

of germ stem cell populations. Additional support for the role

of DAZ in spermatogenesis is provided by an examination of the Drosophila homologue boule, in which a loss of function mutation results in azoospermia.36 Recent data indicate that multiple copies of DAZ are present in the AZFc region and that a functional homologue (DAZLA) exists on human chromosome 3.37,38 Thus, a direct association between deletions in DAZ and azoospermia is complicated by multiple copies of the gene and by the

abundant expression of its autosomal homologue in the testis. In addition, as

with RBM, this deletion is present in only a fraction of the patients studied, suggesting

that other Y loci and likely other chromosomes are involved

in the complicated phenotype of azoospermia or severe oligozoospermia. To

date, there has been no formal proof that DAZ is essential for human spermatogenesis, because no intragenic mutations

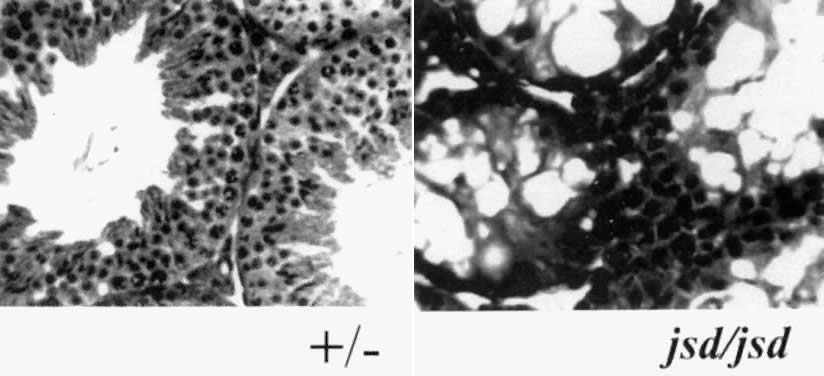

have been found.39 A recent report by Ruggiu and co-workers40 on gene targeting in the mouse demonstrated that the autosomal mouse homologue

of DAZ (Dazla) is essential for the development and survival of germ cells in the ovary

and testis. Much remains to be resolved about the role of DAZ in spermatogenesis; it is clear, however, that DAZ remains a candidate azoospermia gene with a likely role in the etiology

of some types of infertility. In 1996 a new gene mapping to AZFa was described on the basis of its homology

to the Drosophila developmental gene fat facets.41 This gene, DFFRY, has a homologue mapping to the X chromosome and is expressed in many

human tissues, including the testis. It encodes a protein whose sequence

suggests a function in the regulation of protein stability via the

ubiquitin pathway. In a recent report, DFFRY was deleted in three azoospermic patients42: two had a testicular phenotype resembling Sertoli-cell-only syndrome, and

the third exhibited diminished spermatogenesis. This is the first

gene from AZFa that has been reported to be deleted in azoospermic persons; its

further characterization is ongoing. The transcriptional map of the Y chromosome was recently expanded by Lahn

and Page,43 who reported isolation of a number of new genes mapping to various regions. Figure 3 shows the latest transcriptional map of the Y chromosome; included are

these new sequences. The newly isolated genes fall into two classes: single-copy

genes with a wide range of expression and homology on the X, and

multicopy genes with no X homologues that appear to be expressed

specifically in the testis. Of particular interest are those new genes

located in the AZFa-c regions, DBY and TB4Y (AZFa), E1FAY (AZFb), PRY, and CDY (AZFc). Although one may speculate about the function of these genes based

on their homology to other known genes, much more information is

required before specific biological functions may be assigned. It is quite

clear, however, that there are a number of genes in those areas of

the Y chromosome known to be associated with infertility, and that there

are likely more to be found.  Fig. 3. Transcriptional map of the human Y chromosome. Deletion intervals, and

the currently identified genes or pseudogenes mapping to each respective

interval, are indicated. Gene names for SRY, ZFY, SMCY, DFFRY, RBM, and DAZ have been discussed in the text. Additional gene names are: DBY (dead box Y), TBY4 (thymosin B4, Y isoform), EIF1AY (translation initiation factor 1A, Y isoform), UTY (ubiquitous TPR motif Y), CDY (chromodomain Y), BPY1,2 (basic protein Y1 and Y2), XKRY (XK-related Y) PRY (PTP-BL-related Y), TTY1,2 (testis transcript 1 and 2), TSPY (testis-specific Y transcript), AMELY (amelogenin Y).(Adapted from Lahn BT, Page D: Functional coherence of the human Y chromosome. Science 278: 1997) Fig. 3. Transcriptional map of the human Y chromosome. Deletion intervals, and

the currently identified genes or pseudogenes mapping to each respective

interval, are indicated. Gene names for SRY, ZFY, SMCY, DFFRY, RBM, and DAZ have been discussed in the text. Additional gene names are: DBY (dead box Y), TBY4 (thymosin B4, Y isoform), EIF1AY (translation initiation factor 1A, Y isoform), UTY (ubiquitous TPR motif Y), CDY (chromodomain Y), BPY1,2 (basic protein Y1 and Y2), XKRY (XK-related Y) PRY (PTP-BL-related Y), TTY1,2 (testis transcript 1 and 2), TSPY (testis-specific Y transcript), AMELY (amelogenin Y).(Adapted from Lahn BT, Page D: Functional coherence of the human Y chromosome. Science 278: 1997)

|

Identification of Y-specific STSs and genes has provided the clinician

with an opportunity to assess the relative contribution of deletions of

certain Y sequences to the infertile phenotype. Although a direct cause-and-effect

relationship cannot yet be unequivocally assigned to particular

deletions, it is possible to rule out large deletions in certain

areas of the Y chromosome based on STS analysis. In addition, as intracytoplasmic

sperm injection is being increasingly used to assist fertilization

in azoospermic or severely oligozoospermic persons, and because

the Y chromosome of these persons will be passed on to their sons, assessment

of the status of the Y chromosome in these patients is

of considerable value. As mentioned, PCR-based analysis of Yq-deleted

persons has been extensively used to map AZF loci. Multiplex PCR (PCR

using more than one STS per reaction) is a rapid, cost-effective, and

highly reliable method of analyzing the presence (or absence) of large

portions of the Y chromosome (Fig. 4). It must be recognized that small deletions in areas not covered by these

STSs will not be detected, and that this method is only suitable

for assessment of relatively large deletions.  Fig. 4. Multiplex PCR with human Y chromosome-derived STSs. Ten different STSs, including

those for SRY and SMCY in addition to a number of STSs from region AZFc were used in a multiplex

PCR with 250 ng of human DNA. Pattern of amplification (upper right) derived from four normal males, with female DNA used as a negative control. Mix

A consists of STSs sY14, sY134, sY143, sY 255, and sY243. Mix

B consists of STSs SMCY, sY254, sY149, sY269, and sY159. Products were

electrophoresed on 3.5% agarose gels (left ); size markers are indicated. A 250-ng DNA sample (lower right) from an XX male was amplified with primers in mix A and B. Amplification

is seen with only the SRY STS, indicating that a small portion of the Y chromosome is present, which

includes SRY but lacks all other STSs.(Nell and Boettger-Tong, unpublished data) Fig. 4. Multiplex PCR with human Y chromosome-derived STSs. Ten different STSs, including

those for SRY and SMCY in addition to a number of STSs from region AZFc were used in a multiplex

PCR with 250 ng of human DNA. Pattern of amplification (upper right) derived from four normal males, with female DNA used as a negative control. Mix

A consists of STSs sY14, sY134, sY143, sY 255, and sY243. Mix

B consists of STSs SMCY, sY254, sY149, sY269, and sY159. Products were

electrophoresed on 3.5% agarose gels (left ); size markers are indicated. A 250-ng DNA sample (lower right) from an XX male was amplified with primers in mix A and B. Amplification

is seen with only the SRY STS, indicating that a small portion of the Y chromosome is present, which

includes SRY but lacks all other STSs.(Nell and Boettger-Tong, unpublished data)

|

In a recent study by Foresta and associates,44 using samples from subjects with well-defined forms of idiopathic testicular

damage (azoospermia with SCOS and oligozoospermia with hypospermatogenesis), 37.5% of

patients with azoospermia had one or more Yq STSs

missing. Twenty-two percent of patients with severe oligozoospermia

were also missing one or more of these STSs. Fertile controls and the

fathers or brothers of these patients did not show any abnormality, indicating

that these were de novo deletions. Of the deletions observed

in this highly selected group of patients, 72.7% overlapped the DAZ gene and 36.4% overlapped the RBM gene; 18.2% of patients had deletions outside of both DAZ and RBM, confirming other reports suggesting that other genes in interval 6 may

be associated with infertility.39,41 In addition, the severity of the phenotype was not correlated with the

severity of the deletion, indicating that other genes outside of AZF

may modulate the effects of AZF deletions. In this regard, it is noteworthy

that even in this highly selected population, the vast majority (62.5%) of

patients have no detectable Yq deletions. Thus, either small

deletions unamenable to PCR analysis in as yet unidentified genes are

responsible for these phenotypes, or there are other genes not on the

Y chromosome that participate in the regulation of spermatogenesis. The

latter hypothesis will be considered in the next section. |