The condom (also known as a prophylactic, rubber, sheath, or French letter) is

the only male method of contraception available besides coitus

interruptus (withdrawal) and male sterilization. Its invention is attributed

to Gabriel Fallopio (1564).41 It is one of the oldest and most extensively used contraceptives. The

worldwide upsurge of STDs as well as the unstoppable pandemic of HIV/AIDS

contributed to dilute most of the reservations about condoms and its

use held by society at large. Because of its excellent record of infection

prevention and contraceptive protection, its availability, and

simplicity of use, the condom has become the darling of family planning clinics. It offers protection against unintended pregnancy

and serves as the greatest defense against acquiring an STD or

HIV infection; its historical role in the prevention of STDs is unmatched

by any other method of contraception. Protection, however, is not 100% in

either case. There is consistent clinical evidence from prospective

studies of discordant couples, in which one partner is infected

with HIV and the other not, that latex condoms used correctly during

every act of sexual intercourse are very effective, not only in preventing

unintended pregnancy but also HIV transmission STDs.42,43,44,45 When used correctly during each sexual act, condoms are very effective

in preventing unintended pregnancies and STDs. In this dual capacity, condoms

may be regarded as the contraceptive gold standard against which

all other contraceptive methods should be gauged. In strict comparison, most

other contraceptive methods fall short, in fact, considering

the specifications for an ideal contraceptive: high effectiveness, safe, reversible, inexpensive, free from side effects, light and inconspicuous, aesthetically

acceptable, self-administered, simple to use, requiring

no special skills or professional intervention, easy to store

and distribute, offering effective prevention against STD infection, long

shelf life, and use independent of sex. Male condoms answer with

ease all those requirements except the last.46 Condoms also have an important role to play in the rare cases when women

are hypersensitive (atopic allergy) to contact with semen. Condoms are widely available, easily obtainable, and reasonably inexpensive (even

provided without charge by many family planning and STD clinics

and some student health services). They do not require prescription

or fitting. They have virtually no contraindications or side effects, except

occasional allergy to the latex rubber47,48 or the powder or lubricant by either partner. Problems possibly related

to being powdered with talc have been reported.49,50 Latex allergy is estimated to be 1% to 3% in the general population and 6% to 7% in

persons frequently exposed to latex (health workers).7 Condoms are inconspicuous. They are simple to use, and their use is easy

to teach and understand, even by people with limited or no education. To

a certain degree, condoms constrict the penis and may attenuate

somewhat glans sensitivity. This might inhibit erection in some users; however, in

others, it may be a bonus that translates into prolonging

coitus by delaying ejaculation. Condoms are an ideal method for sporadic

or unanticipated coitus, for those who have sex infrequently, or for

those who are faced with an unexpected sexual encounter. Condoms are

a responsible alternative method for couples who wish to share the responsibility

for contraception, as well as when immediate assurance of

successful protection against conception is psychologically important

to either partner. Condoms are recommended as an interim method before

hormonal contraception may be started or an IUD inserted. Some women

like the condom because they prefer the man to take the contraceptive

responsibility and rely on his decision making or because they want

to avoid contact with the ejaculate or postcoital messiness. Table 3 lists the indications and contraindications for condom use. Table 3. Indications and Contraindications for Condom Use

Indications Male Male contraceptive control preferred

Genital or penile disease, cystitis, urethritis, including active sexually

transmitted disease

Sensitivity or allergic reaction to vaginal secretions

Premature ejaculation

Female Male control preferred

Unreliable sexual partner

Vaginitis even under treatment

Contraindications to systemic contraceptives and intrauterine contraceptives

devices (IUDs)

Wants proof that semen was not released in the vagina

Aversion to contact with semen or allergy to it

Rejects hormonal contraceptives and foreign body (IUDs) inserted in her

body

Psychological, cultural, or religious conflict with personal use of contraception

Temporary methods when: Sporadic coitus or a regular sexual relationship is not established

During menstruation if coitus is to occur

During midcycle for extra protection while using a diaphragm, cap, or the

rhythm method

While waiting to start a systemic contraceptive or the insertion of an

IUD

When on oral contraceptive pills, injections, or several were missed

During the first cycle on minidose pill

Postpartum until the involution of the uterus and cervix permits the insertion

of an IUD, a cervical cap, the vagina permits fitting of a diaphragm, or

the stopping of lactation allows the use of hormonal combined

oral pills, injections, or implants

Both sexual partners Male control favored

Casual sex encounter or infrequent intercourse

At risk STDs/HIV infection

Active or suspected STD, including history of or inactive viral STD

Urinary tract infection (UTI) until treated

Interim method until a reversible method can be prescribed, an IUD inserted

or sterilizationis performed

Contraindications Either partner or both sexually irresponsible; cannot be trusted will use

the condomwell and consistently

Allergy to latex by either partner

Disruption or interruption of sexual play inhibits sexual interest or expression

STD, sexually transmitted disease; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus

Modified from Sobrero AJ Sciarra JJ: Contraception, In Cohn HP (ed): Current

Therapy 1978, Baltimore, WB Saunders Company, 1978

Drawbacks or perceived negative attributes of the condom are its historic

connection with illicit sex, promiscuity, and distrust of the partner's

health. Like all barrier contraceptives, condoms necessitate

persistent, recurrent motivation to achieve dependable protection against

pregnancy, STDs, and HIV infection. It must be used correctly at

each sexual engagement. An often-mentioned drawback is the need to interrupt

lovemaking to place it; however, resourceful couples may surmount

this by making the placement of the condom part of sexual foreplay

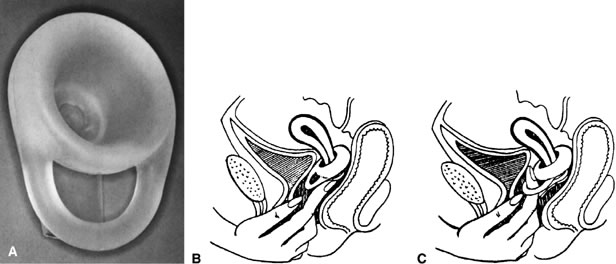

and a more erotic experience. Condoms are made of latex rubber, polyurethane, and natural membranes (Lamb's

cecal pouch). Most commercially available condoms are made

of latex rubber. They come in an astounding variety of shapes (e.g., blunt

or with a reservoir tip, ribbed, speckled, peppered with dots, contoured, with

a helix or spiral rib, with a loose pouch over the glans

or the penile shaft). Condoms come in a kaleidoscopic variety of colors, combinations, even

fluorescent, and flavored, with up to 16 different

tastes. They come in different sizes: standard (170 mm long and 50 mm

wide); long, 30% larger; 45%, extra-large; 6%, narrower; 15%, shorter

and 6%, narrower. They come as extra-strength and extra-thin. They

may be lightly powdered or lubricated with silicone or a water-soluble

spermicide or without spermicide, or a desensitizing product. Their

variety seems to be limited only by the imagination of the manufacturers. Indications

are that there is a market for such diversity and attesting

to the contemporary losing of old social restrains about sexual

intimacy. Usually, condoms are neatly rolled and packaged flat in paper, plastic, or

aluminum foil. They have a long shelf-life, especially

if they are protected from direct sunlight, heat, oily substances, and

ozone, all of which contribute to rapid latex decay.51 Latex condoms lubricated with a spermicide and packaged in aluminum foil

should be favored. However, there are no studies that show that condoms

lubricated with a spermicide are more effective than those unlubricated. Condoms

with spermicide decrease the risk of PID (pelvic inflammatory

disease), infertility, and ectopic pregnancy. Lubrication may

increase slippage.52,53,54,55 Rear entrance that is lengthy and vigorous coitus increase ruptures. Approximately

one condom break occurs per 100 acts of coitus; however, reported

figures indicate a range between 0% and 12%, with most publications

giving figures of 2% to 5%.52,53,54,55 In a U.S. survey with a breakage rate of one to 12 per 100 episodes of

vaginal intercourse, one pregnancy resulted from every three condom breakages.56 During manufacture, condoms are individually tested electronically for

holes and imperfections and must meet the stringent standards set by

the American Society for Testing Materials and the U.S. Food and Drug

Administration (FDA).59 In the United States, condoms are imprinted with the date of manufacture

or an expiration date. Aging seems to be the best predictor for condom

breakage. However, just as important is how they are packaged and

stored and how are they handled when used. Latex condoms form a continuous, impervious

barrier to bacteria and viruses. In vitro laboratory tests have shown that latex condoms provide effective protection

against gonorrhea, nongonococcal urethritis, Chlamydia trachomatis, cytomegalovirus, human papillomavirus, herpes simplex virus, HIV, and

the much smaller hepatitis B virus.6,7,57,58,59 One FDA study found that fluorescent polystyrene microspheres similar

in diameter (110 nm) to the HIV virus (90 to 130 nm) could pass through 29 of

unlubricated latex condoms (p< .03). The harsh physical conditions of the in vitro test under which the study was performed included 30 mL of a watery suspension

of the particles at a concentration 100 times that reported for

the average normal human ejaculate (3 mL) with a pressure of 90 mmHg

over 30 minutes. The authors acknowledge the superior capacity of the

latex condoms in containing HIV virus.55a Seamen on leave in a port with a high prevalence of infected commercial

sexual workers produced striking proof: none of 29 sailors who reported

using condoms became infected, but 71 (14%) of 499 sailors who did

not use condoms became infected with gonorrhea or nongonococcal urethritis.3 In a project that counseled HIV-discordant couples every 6 months, over 6 years

there was no HIV seroconversion.58 Women who are partners of condom users are less likely to become HIV positive.60,61,62 One study followed 245 HIV-discordant couples for an average of 20 months. Among 124 who

related using condoms at every coitus, no new cases

of HIV were detected, even though approximately 15,000 sexual intercourses

were reported. Among the 121 couples who used condoms irregularly, 12 new

cases of HIV resulted, a 4.8 incidence rate per 100 person-years. Couples

who used condoms more than half the time had approximately

the same number of HIV seroconversions among the spouses previously

HIV negative than among those who rarely used a condom.63 Most users of condoms are more worried about avoiding unwanted conception

than preventing an STD; however, this important personal and public

health aspect of contraception never should be relegated to a secondary

role. It is worthwhile to emphasize that the prevention of STDs may

prevent future infertility17,18,26,27,28,29,30 and cancer of the cervix.20,21,22,23,24 Barriers to condom use among women ages 15 to 30 years attending four

Planned Parenthood clinics were related to two restricting factors: pleasure

and intimacy, and low perceived need.64 Nonoxynol-9 (N-9), the spermicide used in most lubricated condoms, may

cause the release of a natural rubber latex protein that may increase

the chance of subjects having a hypersensitivity to latex develop. Natural

rubber latex protein levels leached from latex condoms vary from

brand to brand: condoms lubricated with N-9 have a fourfold to fivefold

increase of natural rubber latex protein compared to the same brand

without the spermicide.47 For latex-sensitive persons, even condoms without N-9 may cause an allergic

reaction.47,48 Latex allergies and urinary tract infections (UTIs) associated with barrier

contraceptive use are problems that only a few people experience. Although N-9 may protect against HIV infection, it is unclear whether the

genital irritation associated with latex allergy or N-9's local

effect may increase the individual risk of infection. Such sensitivity

may preclude correct use of condoms by susceptible persons; hence, they

may be exposed to infection because of failure to use condoms rather

than as a direct effect of using them. Condoms lubricated with N-9 have

been associated with an increased frequency of vaginal and UTIs

with Escherichia coli versus condoms without the spermicide.68,69 UTIs increased with frequency of condom exposure from 0.1 (95% confidence

interval, 0.65 to 1.28) for weekly or less during the previous month

to 2.11 (95% confidence interval, 1.37 to 3.26) for more than once

a week. Exposure to N-9-lubricated condoms produced a higher risk of UTI

with odds ratios increasing from 1.09 (95% confidence interval, 0.58 to 2.05) for

use weekly or less to 3.05 (95% confidence interval, 1.47 to 6.35) for

more frequent use.59 Data on pregnancy rates with condoms are limited. Reported condom failures

range from 1.2% in the United Kingdom to 60% in the Philippines, with

most studies between 4% and 14% in the first year.59 In the various National Surveys of Family Growth, high-parity women aged 25 to 34 years

who smoked and had used the method for less than 2 years

had a pregnancy risk of 14.7.13,70 The contraceptive effectiveness of the condom is acknowledged to be less

than that of oral contraceptives, hormonal injections and implants, and

the IUD; however, when condoms are used consistently and correctly, more

so with an adjuvant (e.g., contraceptive cream, jelly, foam, or

suppository) placed precoitally in the vagina, their use effectiveness

is very high. They may even match the use effectiveness of the pill, which

requires daily motivation, even when sexual activity is sporadic. Kestelman

and Trussell34,79 made a computer model of the use of condoms and spermicides simultaneously

and arrived at a probability failure during perfect use of both of 0.05%, which

is lower than that reported by perfect use of combined

oral contraceptives. Latex condoms fail most frequently because they are

not used than because of imperfections. Skin condoms made from the cecum of some lambs are also available. They

are preferred by some users, who claim higher sensitivity. Their thickness

is similar to that of rubber latex condoms (approximately 0.07 to 0.08 mm). They

are considerably more expensive and not as easy to find. No

use-effectiveness data are available on natural membrane condoms. They

represent less than 1% of the condoms sold. They must be kept

moist to prevent cracking, so they come with an excess of lubricant. They

are reliable for contraception and prevention of bacterial STDs, but

their ability to impede the passage of all types of viral STDs has

produced conflicting results in laboratory studies. They are considered

acceptable for the prevention of bacterial diseases but not reliable

for the prevention of most STDs of viral cause. Nonlatex condoms have been developed to obviate the problem with latex

allergy. Male synthetic condoms are manufactured using a dipped process

similar to latex condoms or a cut-and-seal process using a synthetic

elastomeric film. They are less elastic and wider than latex condoms, making

them less constrictive. Avanti is the only commercially available

synthetic male condom. It is made from Duron, a thermoplastic polyester

polyurethane. Avanti looks like a straight-sided, reservoir-tipped

condom. It is wider, approximately 65 mm when lying flat versus 52 mm

for the standard latex condoms. Avanti had a larger breakage rate than

latex condoms. Tactylon, another plastic condom made by the dipping

process from another synthetic elastomer, has been cleared by the FDA, but

it is not found commercially. Three Tactylon models were manufactured (standard, baggy, and with a wider closed end of 80 mm) to allow

greater comfort by diminishing glans constriction and to provide a more

elastic, standard shape condom. Tactylon also had a larger breakage

rate than latex condoms. Ezon, a synthetic elastomeric condom, not cleared

by the FDA, has a new design. Rather than being rolled on like

latex condoms, Ezon is slipped onto the penis; it can also be donned from

either end. Ortho McNeill Pharmaceutical of Canada and Carter-Wallace, Inc, are

two other companies involved in the manufacture of synthetic

elastomeric condoms. According most reports, they brake and slide

more often than latex condoms.71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79 It is unlikely that a physician will have to provide instructions on condom

use, but in some situations, as when dealing with the sexually uninitiated, full

discussion of this method, even its demonstration, may

prevent anguish and needless hardship. Occasionally, it may be important

to teach the social skills required to ensure condom use by a reluctant

partner. Condom use can be shown using one of the available wooden

or plastic models, a test tube of adequate size, or any other appropriate

object. Never assume that because proper condom use seems so obvious, it

will be used correctly. The following advice should be offered

to the potential user. The condom should be applied over an erect penis

before any contact with the partner's body or genitals takes

place. If the man is uncircumcised, the foreskin should be pulled back

before condom placement. A small length may be unrolled over one or

two fingers and then placed on the penis. The rolling rim of the condom

should be outside. Care should be taken that no air is trapped at the

condom tip. The closed end of the condom should be pinched and held

with the fingers of one hand; this space allows for penile thrusts and

preserves glans sensitivity while allowing room for the ejaculate. The

rest of the condom is rolled completely over the shaft of the erect

penis. After ejaculation and before penile detumescence, the penis should

be withdrawn from the vagina while holding the sheath with the fingers

pressing against the base of the penis to keep it from slipping off

and to avoid spilling semen into the vagina. Buy condoms of good quality, packed in aluminum foil, preferably lubricated

with spermicide (unless allergic to them). Use a new condom every

time, and also if there is a suspicion that the condom may be damaged

or has not been placed properly, even while using it. Do not unroll the

condom or inflate it for testing, because very likely it will be ruined. All

condoms are tested electronically during manufacturing. Throw

away any condom that is or looks dry or brittle; one that seems to have

been damaged by fingernails, rings, or so forth during placement; or

one that was not placed correctly. After ejaculation, withdraw the

penis before it becomes soft while holding the condom against the base

of the penis; take special care to avoid spilling semen. If desired, after

intercourse, inspect the condom for tears or holes by urinating

into it before removal. Dispose of the condom in an appropriate, discreet

manner. |