Hormone Therapy ESTROGEN THERAPY Estrogen therapy has many advantages. Recently, however, The National Institute

of Health halted a longitudinal hormone replacement study on

the basis that there was increased risk for heart disease, breast cancer, and

ovarian cancer.43,44,45,46 As a result, patients are now closely involved in the decision-making

process, and it is the responsibility of the physician to thoroughly

discuss the options and risks with patients and help them make informed

decisions. In many instances, a safer and more effective medication could be prescribed

in lieu of HRT, such as raloxifene or a bisphosphonate for bone

demineralization, statins for lipid disorders, and aspirin for coronary heart disease and stroke prevention. It is important to educate

patients about the level of increased risks. A 26% increase

in the risk of breast cancer means that if 10,000 women were using

HRT for 1 year, eight more will have breast cancer.47 The bottom line is that the doctor must help each woman weigh the risks

and benefits of HRT. Estrogen may relieve hot flashes, improve clitoral

sensitivity, increase libido, and decrease pain and burning during

intercourse. Local or topical estrogen application relieves symptoms of

vaginal dryness, burning, and urinary frequency/urgency. In perimenopausal, menopausal, or

oophorectomized women, reports of vaginal irritation, pain, or

dryness may be relieved locally with low-dose

topical estrogen cream, vaginal estradiol rings, or vaginal estradiol pellets, which may help to minimize the risks of estrogen. TESTOSTERONE The only FDA-approved testosterone replacement available to women is methyltestosterone, indicated for menopausal

women, used in combination with estrogen (Estratest), for

symptoms of inhibited desire, dyspareunia, or lack of vaginal lubrication, as

well as for its vasoprotective effects. A testosterone patch is presently being tested, and early trials indicate that the patch

may improve sexual activity and help create overall sense of well

being.48 According to the Princeton Consensus Panel on Female Androgen Insufficiency, if

a woman exhibits symptoms of low testosterone (e.g., low libido and decreased energy and well-being), it

is important to first determine an alternative explanation for these

symptoms. This means ruling out major depression, chronic fatigue

symptoms, and the range of other emotional and relationship conflicts

that may impact on a patient's desire and happiness. The next step

is to determine if the patient is in an adequate estrogen state and, if

not, to consider the pros and cons of replacement.49 The physician should measure the patient's testosterone levels, which should include at least two to three measures of total and

free testosterone. Normal value range for total testosterone is 49 to120 ng/dL, and for free testosterone it is 3.0 to 8.5 pg/mL for premenopausal women. Normal value range

for total testosterone for postmenopausal women is 3.0 to 6.7 pg/mL. If the patient has a

treatable cause for the androgen deficiency (e.g., oral estrogens

or contraceptive use), treat the specific causes by changing medications. If

not, consider a trial of androgen replacement therapy. There are conflicting reports regarding the best way to use testosterone, in

particular, in premenopausal women. Any premenopausal woman treated

with testosterone must be on some form of reliable birth control and understand the risks. Topical

vaginal testosterone is often used in premenopausal women as a first step because it is delivered

locally and is also used for treatment of vaginal lichen planus. Topical testosterone (methyltestosterone or testosterone propionate) preparations can be compounded in 1% to 2% formulations

and should be applied up to three times per week. The

suggested dose of oral testosterone (pill or sublingual spray or lozenge) for premenopausal and

postmenopausal women range from .25 to 1.25 mg/day. The dose should

be adjusted according to symptoms, free testosterone levels, cholesterol levels, triglyceride levels, HDL levels, and LFT. The

potential side effects of testosterone include weight gain, clitoral enlargement, increased facial hair, and

hypercholesterolemia. Testosterone can also be converted into estrogen, so

physicians should take this risk into account when counseling their

patients. Increased clitoral sensitivity, decreased vaginal dryness, and

increased libido have been reported with the use of a 2% testosterone cream. Preliminary studies on the effectiveness of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) as

a form of testosterone replacement are promising as well.50 Pharmacological Therapy Aside from hormone replacement therapy, all medications listed here, although

used in the treatment of male erectile dysfunction, are still in

the experimental phases for use in women. Currently, we have limited

information regarding the exact neurotransmitters that modulate vaginal

and clitoral smooth muscle tone. Recently, nitric oxide (NO) and

phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5), the enzyme responsible

for both the degradation of cGMP and NO production, have been identified

in clitoral and vaginal smooth muscle.2 In addition, organ bath studies of rabbit clitoral cavernosal muscle strips

demonstrate enhanced relaxation in response to the nitric oxide

donors, sodium nitroprusside, L-arginine, and sildenafil. SILDENAFIL Functioning as a selective type 5 (cGMP specific) phosphodiesterase

inhibitor, sildenafil decreases the catabolism of cGMP, which is

the second messenger in nitric oxide-mediated relaxation of clitoral

and vaginal smooth muscle. Sildenafil may prove useful alone or

possibly in combination with other vasoactive substances for treatment

of female sexual arousal disorder. Phase two clinical studies assessing

safety and efficacy of this medication for use in women are currently

in progress. A recent study demonstrated that sildenafil is successful

in treating female sexual arousal disorder in hormonally replete

women without psychosexual causal factors in a placebo-controlled

study.51,52 Other studies have found that sildenafil helps to alleviate arousal problems

associated with aging and menopause and secondary to SSRI use.30,32 L-ARGININE This amino acid functions as a precursor to the formation of nitric oxide, which

mediates the relaxation of vascular and nonvascular smooth muscle. L-arginine

has not been used in clinical trials in women. However, preliminary

studies in men appear promising. A combination

of L-arginine and yohimbine (an alpha-2 blocker) is

currently undergoing investigation in women. YOHIMBINE Yohimbine is an alkaloid agent that blocks presynaptic alpha-2 adrenoreceptors. This

medication affects the peripheral autonomic nervous

system, resulting in a relative decrease in adrenergic activity and

an increase in parasympathetic tone. There have been mixed reports of

its efficacy for inducing penile erections in men, and no formal clinical

studies have been performed in women to date, nor have potential

side effects been effectively determined. PROSTAGLANDIN E1 (MUSE) An intraurethral application, absorbed via mucosa (MUSE), is

now available for male patients. A similar application of prostaglandin

E1 delivered intravaginally is currently undergoing investigation for use

in women. Clinical studies are necessary to determine the efficacy of

this medication in the treatment of female sexual dysfunction. PHENTOLAMINE Currently available in an oral preparation, this drug functions as a nonspecific

alpha-adrenergic blocker and causes vascular smooth muscle

relaxation. This drug has been studied in male patients for the

treatment of erectile dysfunction. A pilot study in menopausal women with

sexual dysfunction demonstrated enhanced vaginal blood flow and subjective

arousal with the medication.53 APOMORPHINE Apomorphine is a short-acting dopamine agonist that facilitates

erectile responses in normal males and males with psychogenic erectile

dysfunction or organic impotence. Data suggest that dopamine is involved

in the mediation of sexual desire and arousal. The physiologic effects

of this drug are currently being tested in women with sexual dysfunction. NITROGLYCERIN Nitroglycerin (glyceryl trinitrate) has been used for more than

a century to relieve anginal symptoms associated with coronary artery

disease. It has been administered to humans via oral, sublingual, intravenous, and

transdermal routes. Nitroglycerin has been found to relax

most smooth muscle, including bronchial, gastrointestinal tract, urethral, and

uterine muscle. It also produces dilation of both arterial

and venous vascular beds. Metabolism of nitroglycerin leads to the formation of the reactive free radical nitric oxide. Recent

evidence suggest that application of nitroglycerin to painful areas, including the genitals, may provide analgesia to the

affected areas.23,54 More work needs to be performed in this area, but many experts are finding

this to be an effective treatment for helping women manage vulvar

pain, especially when in combination with topical estrogen and testosterone creams and vaginal physical therapy. Medical Devices EROS-CTD Eros-CTD is the first FDA-approved treatment on the market

for arousal and orgasmic disorders in women. It is a small, hand-held

medical device that works by applying a genital vacuum to the

clitoris, increasing blood flow to the clitoris and surrounding tissue. Initial

clinical trials showed improvement in premenopausal and postmenopausal

women with female sexual arousal disorder or female orgasmic

disorder.55,56 INTERSTIM THERAPY InterStim therapy was designed to treat urinary incontinence. The therapy

involves placing a lead in the S-2 to S-4 region. The

lead is passed to a neurostimulator, which sends mild electrical pulses

to the sacral nerve. Many women who have undergone this procedure have

anecdotally reported that their sexual arousal and ability to achieve

orgasm increased. More retrospective and prospective research testing

this device for orgasmic improvement is currently underway. Other Therapies GYNECOLOGIC PHYSICAL THERAPY Pelvic pain, vaginismus, and vaginal atrophy can often be treated with

physical therapy. When muscle tension or spasm appears to be a factor, a

physical therapist, through gentle massage, biofeedback, or other techniques, can

help restore normal muscle balance. Physical therapy can

also be helpful for women who have vaginal, rectal, or uterine prolapse, and

can be helpful to those women with incontinence and weak Kegel

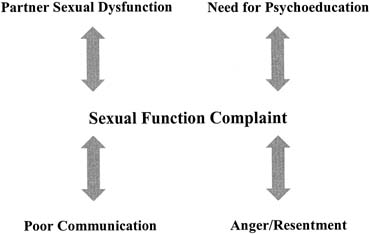

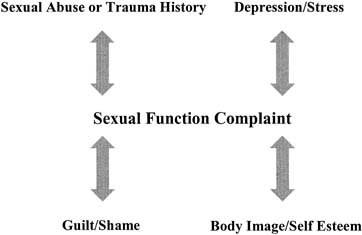

muscles. TALK THERAPY More often than not, there are psychological and relationship factors contributing

to a sexual problem. Even if the primary etiologic domain

is physical, there are emotional and relationship outgrowths to the problem

that cannot be ignored. Similarly, not all women are candidates

for medical intervention and are better suited for other psychological

or couples therapies.19,56,57 Usually the best treatment is a combination of medical and talk therapy. It

should be noted here that beginning talk therapy without evaluating

the potential medical causes for female sexual dysfunction is not

recommended. Extensive talk therapy with a woman with undiagnosed medical

issues can be a frustrating experience for the patient and caregiver. The ideal way to determine candidates for medical intervention in a clinical

setting is to collaborate with a trained sex therapist. If the medical

practitioner has access to a therapist on site, evaluation and

diagnosis are optimized. Unfortunately, not all physicians have access

to or facilities for incorporating a sex therapist into their practice. In

this case, it is crucial for the physician to perform an extensive

assessment of the sexual symptoms and the context in which they are

experienced. This process not only entails a good global history but

also includes clarification of the sexual concern in a way that allows

psychosexual “red flags” to be identified so that an appropriate

therapy referral can be made (Table 4). Table 4. Psychosexual Red Flags for Further Assessment*

| The symptoms are life-long, not acquired |

| The symptoms are situational (e.g. do not exist when stress removed

or when with another partner) |

| The patient has a history of sexual abuse or trauma |

| The patient has a psychiatric history |

| The patient has a history of or is presently experiencing depression and/or

anxiety or stress |

| The couple experiences relationship conflicts (e.g. lack of intimacy, conflict, etc.) |

| The partner has a sexual dysfunction |

*None of these factors guarantee the problem is psychosexually based

but simply point to a need for further clarification by a trained sex

therapist.

The key to making a therapy referral is helping the patient understand

how talk therapy fits into the treatment equation. It may need to be clarified

that although you do not think her problems are “all in

her head,” she would benefit from talk therapy as well as medical

treatment. Often if the physician supports the role of talk therapy

and helps the patient understand how it will be incorporated into her

treatment plan, rather than feeling “pawned off” to someone

else, she will feel validated and encouraged. Even if the physician

refers the patient to a sex therapist, if it is discussed as part of

the treatment plan, the patient will usually respond positively. |