Diagnosis and Therapy of Benign and Preinvasive Disease of the Cervix

Authors

INTRODUCTION

Identifying premalignant and benign diseases of the cervix and selecting an appropriate treatment path can be challenging. Often, benign cervical disease appears malignant and malignant disease can be hidden from view. The focus of this chapter is to describe the range of diseases from benign through premalignant diseases of the cervix and describe options for management as well as guidelines that help identify those with potentially more serious or invasive diseases.

Cervical lesions range from being visible only with an instrument that augments sight such as a colposcope to gross abnormalities. Diagnosis and management requires a compilation of visual (including colposcopy or staining), tactile, and laboratory assessments (HPV tests, Papanicolaou smears, cultures, biopsy, etc.). The details of colposcopy, one of the major tools in delineating these lesions, as well as cervical screening are covered elsewhere in the Global Library of Women's Medicine, so this chapter covers an expanded area for management.

Choosing management strategies globally can be impacted by the availability of trained clinicians, equipment, and laboratory support. Where there are existing data that clarify optimal choices for management in settings that lack one or more resources, these are described.

BENIGN LESIONS OF THE CERVIX

Triage of cervical lesions begins with history and symptomatology. Previous history of any malignancy, particularly those that are prone to metastases, including breast, melanoma, gestational trophoblastic disease, and high-grade malignancies of the gastrointestinal tract or lung, may be a clue that this lesion represents a rare metastasis to the cervical area putting this lesion out of the benign category. Previous history of cervical surgeries, abnormal HPV or Pap smears, uterine polyps, or myoma all help guide the direction of the examination. Lesions characterized by bleeding and discharge immediately raise the possibility of infection and/or malignancy. Lesions with local pressure symptoms, for example, bladder pressure or urgency, also raise these two diagnoses. Lesions associated with cramping similar to that associated with cervical dilation with childbirth (with or without discharge) raise the possibility of prolapsing uterine or cervical myomas, polyps, or even malignancies. Classic watery or foul discharge could indicate an invasive malignancy, and a gush of fluid raises the question of tubal disease. Thus, eliciting a good history immediately begins to focus the differential diagnosis for the lesion.

The second element of diagnosis is the physical examination. While a full physical examination is often warranted, the elements of a pelvic examination performed before a directed cervical examination are critical in continuing to delineate the diagnosis. Specifically, groin nodes should be palpated first, because enlargement may point to an unexpected infection or malignancy. The skin of the perineum and the mucosa of the vagina are inspected closely and lesions present in this area (for example, condylomata) again refine the differential further. Finally, the cervix itself is carefully evaluated in total. If the characteristics of the lesion are unusual, consideration of additional staining (Lugol’s or acetic acid) or colposcopic assessment is appropriate to allow better assessment of the nature of the lesion and the blood supply to it. Examination of the cervix with a speculum can be challenging. Availability and use of a wide range of sizes of speculums, as well as rigid sigmoidoscopies for women with long vaginal canals or large size can assist in this evaluation. It is always important to remember to examine the vaginal mucosa in the fornix and throughout the vagina as part of a cervical exam to further elucidate the cause of symptoms, as it may be vaginal rather than cervical in nature. Furthermore, malignancies can originate or extend to these areas and a complete exam will define the cancer more effectively.

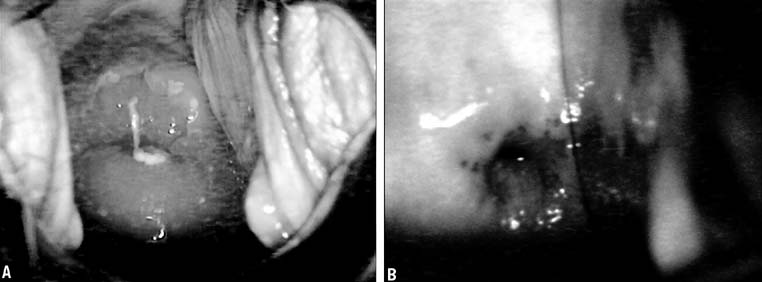

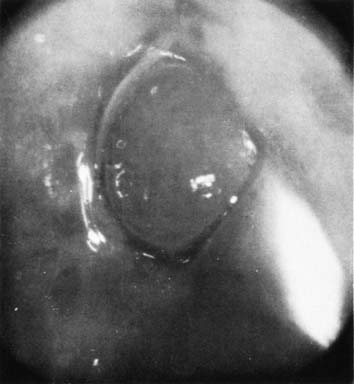

The normal cervix varies throughout life, and understanding this transition is key to diagnosis of differences noted on evaluation of the cervix (Figs. 1A and 1B). Normal cervical epithelium should be uniformly pale pink and the epithelium thick enough that the vascular pattern is generally obscured. The cervical squamous to glandular transformation zone varies throughout life, but areas of gland openings within squamous metaplastic tissue are expected. Without estrogen, with chemotherapy, and with radiation, the epithelium tends to become atrophic with a loss of the underlying vasculature and a whiter appearance as well as regression of the squamocolumnar junction (see Fig. 1B). If the cervix is erythematous, white in appearance, with prominent vascular patterns, friable, or if the area of transformation is beefy or edematous, these are all findings that require explication.

CERVICAL ULCERATIONS

As noted in other chapters on pelvic infections, these infections can also impact the cervical appearance. Primary herpes simplex, for example, can show the characteristic ulcerations on the cervix. Syphilis may occasionally show chancres on the cervical portio. Finally, vaginal/cervical infections can have such severe impact on the cervix that it appears ulcerated. All of these should have adequate findings elsewhere to distinguish them as secondary to infectious agents. Biopsies of the cervix are not warranted when they are secondary to other key lesions in the vulva or vagina.

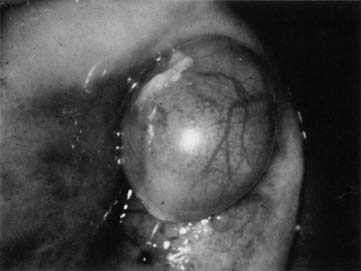

NABOTHIAN CYSTS

Nabothian cysts are common benign findings on the portio of the cervix and are thought to arise in areas of active metaplasia. They represent occlusion of the mucus-secreting glands of the cervix underneath a squamous covering with mucin collecting in a cystic area (Fig. 2). Usually these are small (less than 0.5 cm) and can be multiple; however, cysts up to 5 cm or greater in diameter have been described. They should have a smooth glistening surface with clear or slightly milky contents (Fig. 3). Deviations from this smooth surface, such as erosions or vascular anomalies, should be further investigated and biopsied. Very large cysts have secondary symptoms (such as pressure, heaviness, or urinary retention) unlike the absence of symptoms that characterizes the majority of nabothian cysts.

The natural history of nabothian cysts may be rupture (more commonly) with a subsequent small yellow scar, stabilization, or growth. The majority of nabothian cysts, therefore, require no treatment, and the diagnosis is typically clinically obvious. Large nabothian cysts may benefit from being opened with a loop electroexcision procedure (LEEP) or direct cauterization. The key is assuring that the area fully drains, which may be accomplished by ensuring that the squamous covering is adequately resected or that the base is cauterized to decrease mucus production.

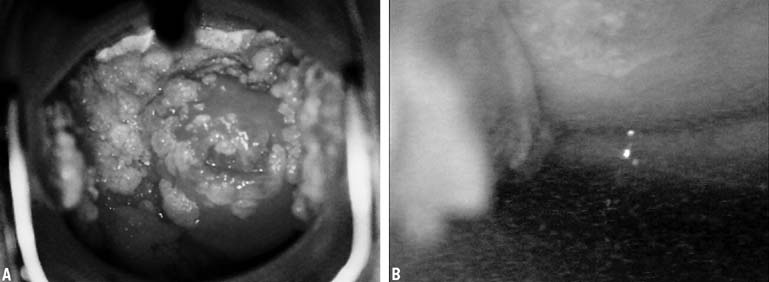

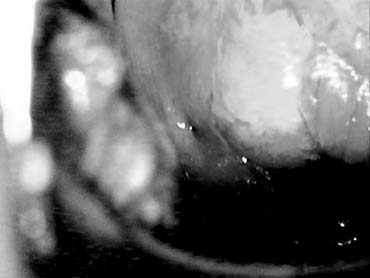

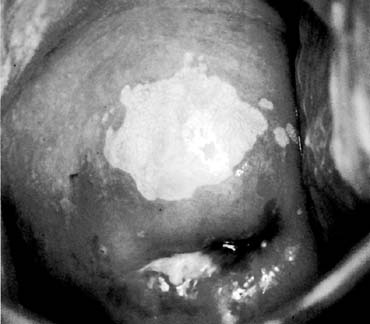

CONDYLOMATA ACCUMINATA

Cervical condyloma can take various forms (Figs. 4A and 4B), but generally they appear as one or multiple clearly delineated, elevated, white plaques on the cervical portio and often extend onto the vaginal apex as well. Small lesions may only be apparent through colposcopic views and acetic acid application after a cytology result of atypical cells of uncertain significance (ASCUS). The larger lesions are commonly friable and can have symptoms of postcoital bleeding that would increase concern for malignancy. If a patient has vulvar condylomata, a careful inspection of the vaginal and cervical epithelium for subclinical or clinically apparent condylomata is warranted. Clearly, full evaluation of these lesions requires cervical screening (HPV/cytology) and biopsy of a typical lesion with or without colposcopy at the initial evaluation. While condylomata are most commonly associated with HPV types 6, 11, 42, 43, and 44 and the potential for malignancy is low, their presence suggests that other HPV strains could be present with higher potential for development of preinvasive or malignant disease.

Management on the cervix differs from vulvar areas where direct application of agents such as TCA (trichloroacetic acid) or imiquimod can be accomplished with little direct absorption. Given the nature of the vaginal and cervical skin, management of these lesions tends to rely heavily on direct removal through the use of biopsy forceps, cautery, LEEP, or laser according to the size and location of the lesion as well as the availability of these modalities. All serve to eliminate the bulk of disease and are assumed to decrease the viral load by virtue of the same.

Management is problematic in women who are pregnant, who are immunosuppressed, or who have chronic recurrence of condylomata. During pregnancy, observation alone is preferred. Removal with LEEP-based therapies might be considered only if there is concern about significant hemorrhage associated with cervical and/or vaginal dilatation at the time of delivery but carries uncertain risks. A significant proportion of these condylomata regress after pregnancy, so therapy is preferentially targeted to the postpartum assessment if they are not thought to be significant enough to interfere with delivery. Use of topical solutions is generally prohibited in pregnancy even for external lesions.

Chronic immunosuppression is commonly associated with chronic low-level cytologic abnormalities of the cervix and the presence of subclinical or clinical condylomata. Rather than recurrent surgical removal, if the patient is able to continue close observation with cytology, and/or HPV subtyping as appropriate and colposcopy on a regular basis, this may well be preferable to multiple surgical interventions. Then, either a change in colposcopic appearance, gross appearance, or cytology/ HPV subtype showing HPV 16 and/or 18 should trigger a biopsy to ensure that any advance in the intraepithelial neoplasia associated with condylomata is identified and appropriately treated. If it remains stable in appearance and screening, then close follow-up may suffice. Options for removal include biopsy and/or removal, cryotherapy, laser ablation, and LEEP.

SQUAMOUS PAPILLOMA

Papillomas that are not HPV-related can occur in the cervix and usually originate from the exocervix near the squamocolumnar junction (transformation zone). These are thought to be related to local irritation or scarring and are usually less than 1 cm. Their natural history is not well described, as the usual intervention for these papillomas is excision to ensure that they do not represent malignancy (Figs. 5 and 6).

LEIOMYOMAS

Leiomyoma is the most common tumor of the uterine body, but it is rare to find it isolated to the cervix. In the cervix, leiomyomas can occur wherever there is smooth muscle, so they can be subserosal, intramural, or submucous in analogy to those in the body of the uterus. Endocervical leiomyomas become symptomatic particularly if an endocervical polypoid leiomyoma prolapses, often with significant cramping and bleeding, or if there is endocervical obstruction with hematometra. Exocervical and endocervical leiomyomas can become large enough to obstruct urethral drainage as well as to prolapse into the vagina and cause bleeding. The decision to remove these masses is generally straightforward, both to adequately diagnose the condition and to alleviate the symptoms. The surgical management of these lesions is best undertaken in the operating room with adequate planning for the potential of abdominal as well as vaginal approaches. Removal generally involves a surgical procedure carefully tailored to the individual patient because of the impingement on bladder, bowel, ureter, and even urethra. Use of endoscopic equipment or a LEEP with a loop that fits can assist in removal. Planning for adequate control of the cervical branch of the uterine artery is always an important element. Removal of pedunculated fibroids in the office setting is generally discouraged, because the upper limits of the lesion can rarely be visualized or easily accessed, and vascular relationships of leiomyoma of the cervix are rarely straightforward.

ENDOMETRIOSIS

Cervical endometriosis (Fig. 7) can mimic multiple lesions, including gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD), because of its highly vascular nature. The etiology of endometriosis in the cervix is unclear, but prior trauma to the cervix and a history of endometriosis are potential clues. History and physical examination to evaluate the likely nature of the lesion, including a laboratory assessment of human chorionic gonadotropin are all prudent before consideration for biopsy or treatment. Biopsy of areas of trophoblastic disease are generally avoided, because the invasive neovascularization that accompanies these lesions may lead to significant hemorrhage, unlike endometriotic implants that are less likely to have postbiopsy hemorrhage. Symptoms from a cervical lesion are generally related to bleeding or discharge, and pelvic pain is more likely referred from endometriotic implants elsewhere in the pelvis. These areas should respond to general therapy for endometriosis (the use of Lupron, for example), and failure to respond should lead to biopsy to confirm the diagnosis.

ADENOSIS

Extension of the glandular epithelium onto the portio and even the vaginal apex is a classic hallmark of exposure to diethylstilbestrol (DES), but it can occur normally in some individuals. As individuals age, the extent of the adenosis tends to decline toward the endocervical os, but islands can remain throughout the upper one-third of the vagina. In the presence of normal HPV testing and cytology and, for DES patients, normal base colposcopy, no further therapy is needed. Biopsy is reserved for areas of questionable vascularity or for worrisome colposcopic findings.

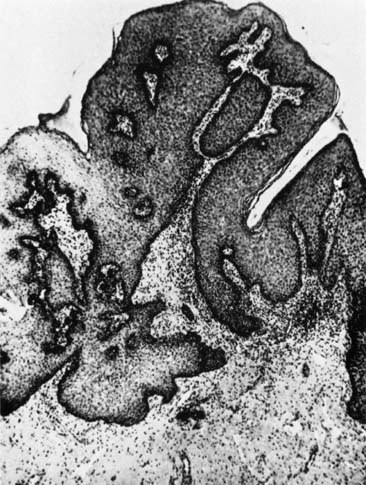

ENDOCERVICAL POLYPS

Endocervical polyps are common and are almost always benign (Fig. 8). They are rarely seen unless they prolapse through the external cervical os, and patients often present with bleeding or spotting that is inconsistent with their menstrual cycle. Their stalk is of variable length and width. The gross appearance of endocervical polyps may vary widely, and does not differentiate them from endometrial polyps, small prolapsing fibroids, nor identify them as benign or malignant by appearance alone. If HPV and cytology screening is normal, a patient is asymptomatic, and the appearance is benign, they can be left in situ.

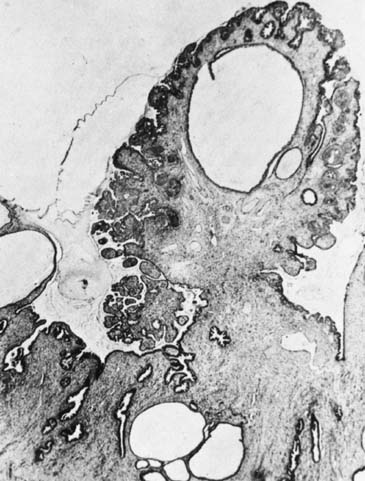

Evaluation of the stalk attachment site is the key to management if removal is indicated. Often simply following the stalk to its base with a cotton swab or probe is adequate. A sonohysterogram may also be helpful if the stalk seems to progress into the uterine cavity. Colposcopy of the prolapsed portion may also give information about the likelihood of malignancy as well as the level of vascularity of the polyp. If the base is narrow and the endocervical portion easily accessed, then removal in the office can be considered. This may require only twisting the base with grasping forceps. Bleeding can occur after removal and endocervical curettage, chemocautery, or electrocautery may be required for control. Multiple polyps or broad-based polyps may require the use of excision, including LEEP and the use of endoscopic ligature systems to control and are best managed in a more controlled environment. Recurrence can occur, although thought to be less with curettage of the base. Pathology of endocervical polyps (Fig. 9) often shows varied degrees of inflammation and edema, and occasionally squamous metaplasia at the tip, accounting for the appearance of normally branching but abundant vasculature and acetowhite epithelium seen on colposcopy of these lesions.

PREMALIGNANT SQUAMOUS LESIONS

A cytologic diagnosis or a positive HPV, to reiterate this for its importance in management, does not make a pathology diagnosis. This is only accomplished by cervical biopsy, usually with concurrent colposcopy. A precise delineation of the size and nature of the lesion with colposcopy or with VIA (visualization with acetic acid) in low resource settings is preferred before biopsy (Figs. 10 and 11). A grossly abnormal lesion visible to the naked eye, with a suggestion of malignancy could be biopsied without either colposcopy or VIA, although these are recommended to identify the extent and location of lesions that are not visible. Management of these lesions is defined by the HPV and/or cytologic history, the patient's risk for malignancy, and the reliability of the patient for follow-up. With the present screening guidelines,1, 2 colposcopy and biopsy of findings has a clearly defined role. Biopsy may be performed with conventional biopsy forceps or with LEEP. Of particular concern is the use of ablative and excision techniques in young nulliparous women. This in combination with the fact that younger women are more likely to spontaneously clear HPV infections has led to screening changes in the new guidelines such that cytology alone (every 3 years if negative) has been recommended for women 21–29 years of age to reduce the rate of unneeded biopsies without significantly impacting detection of the low rate of cancer in this age cohort. For women who have a diagnosed higher-grade lesion (CIN II and III) or a suspicious lesion of the cervix as outlined, primary ablation or excision may be appropriate.

In the global setting with women cared for in a multiplicity of resource settings, initial treatment such as LEEP or cryotherapy rather than interval biopsy might be recommended for a single positive HPV test at a defined age or with a positive VIA, if these are the only available options for screening. The lack of an ability to provide redundant testing or even more than one or two lifetime screenings changes the role of local therapy in preventing malignant disease substantially. The goal in these settings is not to provide a biopsy diagnosis but to primarily treat highly likely pre-invasive disease, in order to reduce the overall occurrence of cervical cancer (see World Health Organization guidelines).2

REMOVAL OF CERVICAL LESIONS

Techniques include thermal ablation (cryotherapy), laser ablation, and excision with biopsy forceps, LEEP, laser, or scalpel. The choice among these options is clinically determined by whether endocervical involvement is present and whether there is an uncertainty regarding the pathology or extent of disease that requires accurate assessment of specific margins of resection. In variable to low resource settings, only one of these may be available. Because laser treatment and surgical excision are outlined elsewhere, the following discussion is devoted to thermal ablation and loop excision.

THERMAL ABLATION: CRYOTHERAPY

Cryotherapy is the primary thermal method in use at the present time. Evidence-based review of cryotherapy by the World Health Organization2 concluded that, while the comparative data were limited, the risk for spontaneous abortions, infections including HIV, and infertility appear to be similar to the general population or acceptable. Cryotherapy may be used for treatment of condylomata or for ablation of low grade CIN. Again, satisfactory pretreatment evaluation and individualization of therapy based on age, disease, and gravidity is important. In particular, if lesions are greater than 75% of the cervical surface, there is high grade dysplasia, or there is disease into the endocervical canal, an excisional approach is recommended (for example LEEP).

Cryosurgery is an office procedure that usually can be performed without anesthesia or analgesia. Occasionally patients will experience discomfort, but it is seldom of a severity to require discontinuation of the treatment. Self-limiting vasomotor reactions characterized by light-headedness and flushing are common. After cryosurgery, patients will usually have 10–14 days of watery discharge requiring four or five sanitary napkins daily. Coitus and intravaginal tampons are not recommended during that time.

Technique

Patients should be treated within 1 week of cessation of menstrual periods.

Most cryosurgical instruments use either nitrous oxide (freezing point of −89°C) or carbon dioxide (freezing point of −65°C). If both are available, CO2 is preferred. Proper freezing requires attention to the pressure within the tanks because a decrease in partial pressure changes the freezing rate of the probe. By changing the rate of freezing, the extent of cryonecrosis can be modified. The pressure within the tanks must be at least 40 kg/cm2 before and at the completion of the freeze. If there is a pressure decrease during cryosurgery, the procedure should be discontinued and repeated with adequate pressure levels.

Probe tips of various configurations are available and should be tailored to individual cervical anatomy. The various flat and cone tips and the 8-mm rod tip are appropriate for most cryotherapy procedures. Areas to be treated should be outlined by a visible lesion or by a colposcopic map, and direct connection of the probe tip to the area to be treated must be possible with the tip chosen.

A thin layer of water-soluble lubricant applied to the tip of the probe allows for better heat transfer between the probe and the cervix, and fills any potential air gaps in the irregular surface of the cervix to provide a more uniform freeze. Freezing of a large ectocervical lesion should begin at the periphery and use overlapping fields of necessary. The ice ball should extend at 4–6 mm beyond the edge of the abnormal epithelium. The depth of cryonecrosis will be approximately 4–5 mm and theoretically should destroy any intraepithelial neoplastic process extending into endocervical glands on the portio. The extent of the ice ball beyond the confines of the lesion is more critical than the length of the freeze. This will usually occur within 2 minutes, so most clinicians use a freeze technique with 3 minutes on, 5 minute thaw, and 3 minute repeat. This was also supported with the WHO guidelines.3

Cryonecrosis and surveillance

Cellular death occurs at a temperature of approximately −20°C. This temperature is within 2°C of the eutectic point of a sodium chloride solution. Cryosurgery produces severe biochemical and biophysical changes resulting in coagulation of the affected tissues. Rupture of the cell wall occurs with the formation of intracellular and extracellular ice crystals. Avascular necrosis is produced by circulatory compromise because of capillary obstruction and stasis.4

Regeneration of the epithelium involves the production of initially immature squamous epithelium, which over time will mature into a stratified squamous layer that replaces the neoplastic process. The entire reparative process requires approximately 3–4 months. Subsequent follow-up should be decided on the basis of individual risk parameters.

Efficacy

Since the introduction of thermal ablation, there has been scepticism about its efficacy in the conservative therapy of CIN. Two concerns need to be addressed. First, factors must be identified that are associated with primary failure of the technique. Second, the ability of the neoplastic process to recur must be considered along with the potential benefits or deficits of a procedure in expediting the long-term follow-up. Observations from British Columbia suggest that for CIN, excisional procedures have a lower rate of recurrence.5 However, the use of cryotherapy with VIA, particularly in settings with no access to LEEP, for screen and treat strategies remains an important option for prevention of cancer.2, 3

LOOP ELECTROEXCISION PROCEDURE

The addition of loop procedures to the outpatient setting has had a significant impact on office treatment of preinvasive disease. For the majority of women, adequate colposcopy and biopsy results must be obtained before LEEP should be performed. Clearly “see and treat” strategies (for example HPV screen and rapid treatment) do not follow this pattern in low resource settings.

Potential obstetric sequelae of treatment

The use of LEEP in young women raises a concern of cervical damage similar to that encountered with surgical excision (conization) of the cervix, and some data suggest that there is a potential for preterm births, premature rupture of membranes, and increase in low birth weight babies.6, 7, 8 The challenge with interpretation of these data is the absence of comparable comparison groups.

A meta-analysis designed to evaluate effect of LEEP on significant prematurity (<32 weeks) and perinatal mortality revealed no association between LEEP procedures and this degree of prematurity. However, this analysis did not address late preterm delivery (34–37 weeks), which is increasingly associated with long-term developmental sequelae in children.9 Multiple smaller studies do have conflicting results and suggest a relationship between LEEP and subsequent preterm birth.

To this end, there are accumulating data that implicate the depth of the excision and the length of the remaining cervix as the key factors in determining the potential obstetric risks associated with this procedure. A small prospective study of 142 women addressed this issue by assessing cervical dimensions by imaging pre- and post-LEEP treatment, and correlating the volume of cervical excision with subsequent pregnancy outcomes. In the 12 deliveries that were evaluated, there was a correlation noted between cervical excision volume and pregnancy duration.10 Number of procedures has also been suggested as a risk factor for subsequent poor pregnancy outcomes, with multiple studies suggesting that risk of preterm delivery is increased in women who have undergone two or more cervical excisions. Additionally, short intervals between cervical excision and pregnancy have been associated with subsequent preterm deliveries in some observational studies. This is significantly more controversial. The suggested mechanism for preterm delivery is the possible incomplete healing of the cervix after the procedure.11 Clearly, data conclusively evaluating obstetric risks associated with LEEP are conflicting, though overall larger studies suggest it is a safe procedure to perform in young, fertility seeking women. While consideration of these possible sequelae is important, it should not keep women from adequate treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia

Technique

LEEP uses high-frequency, low-voltage, electrical energy produced by an electrosurgical unit to excise abnormal tissue. There are a variety of units and electrodes used for LEEP procedures, and the healthcare providers using the instrument must understand the various details of operation of each unit. Some variation of a grounding pad application may be required, and adequate suction ventilation with a microbial filter is required. The choice of electrodes used should be determined by careful colposcopic mapping of the disease before treatment and by the individual contour of the vagina (width) and cervix.

LEEP is best performed when patient is not menstruating for simple visualization. Because the procedure does involve thermal injury and tissue removal, local anesthetic with a vascular constrictor can be injected into the cervical stroma before the procedure. A nonconducting speculum is inserted into the vagina, with the suction ventilation incorporated into the body of the speculum. The cervix may be treated with Lugol's solution for better definition of the lesion. Diathermy power is usually set at 50–60 watts cutting or at 50 watts cutting and 60 watts coagulation. An initial evaluative phantom pass of the selected loop (often approximately 1 cm (10 mm) in width) identifies that the lesion will be encompassed with one or two passes and that no vaginal wall contact will be made.

Large loop excision of the transformation zone (LLETZ) uses a 15 × 7 mm loop and is intended to remove the entire transformation zone. The use of a slow steady movement will reduce thermal injury at the margin. The diathermy unit is turned on only when active movement through the cervix is ongoing. Specimens are then removed for pathologic consultation. This can be performed with one deep or shallow pass, followed by a second pass with a thinner electrode. Then, the base is cauterized with a ball electrode (Fig. 12).

Efficacy

Electroexcision procedures, when used for CIN, have a lower recurrence rate compared to cryotherapy.5 The additional pathologic confirmation afforded by removal of a specimen is an advantage of this technique. The presence of disease at the endocervical margin and the use of LEEP for patients suspected to have endocervical disease continue to pose difficulties, and the data for loop electrosurgical cone biopsies are still developing. The safety of using LEEP with unique populations such as HIV-positive women is emerging and appears to be safe, although recurrence in this population is higher overall.12, 13

SUMMARY

In this chapter, a number of alternatives for the diagnosis and management of benign and premalignant lesions are reviewed. More extensive review for CIN can be found in the screening chapter. The number of alternatives for management on an outpatient basis is continually increasing. For premalignant lesions, however, individualized treatment according to age, diagnosis, pregnancy status, parity, cervical anatomy, and lifestyle risk factors remains critical in assigning patients to different techniques. For women with HIV, particularly those with significant immune compromise, the need to tailor therapy is even greater because the risk of disease recurrence is high regardless of technique. The role of the clinician in wisely choosing among this increasing number of options is critical for the lifelong health of their patients.

REFERENCES

Saslow D, Solomon D, et al. American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology Screening guidelines for Prevention and Early Detection of cervical Cancer. J Lower Genital Tract Disease 2012 16: 205-242. |

|

World Health Organization. Comprehensive cervical cancer control: a guide to essential practice. 2nd edition. 2014 World Health Organization, Geneva Switzerland. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/cancers/cervical-cancer-guide/en/ accessed 7.2015 |

|

World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines: Use of Cryotherapy for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. World Health Organization 2011. Geneva, Switzerland http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2011/9789241502856_eng.pdf accessed 7.2015 |

|

Droegummueller W, Greer BE, Davis JR et al: Cryocoagulation of the endometrium at the uterine cornua. Am J Obstet Gynecol 131:1, 1978 |

|

Meinikow J, McGahan C, Sawaya GF, Ehlen T, Coldman A. Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia outcomes after treatment: long term follow up from the British Columbia Cohort Study. J Natl Cancer Inst 2009;101:721-728. |

|

Crane, JM. Pregnancy outcome after loop electrosurgical excision procedure: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol 2003;5:1058-1062. |

|

Samson S, Bentley J, Fahey T, McKay D, Gill G. The effect of loop electrosurgical excision procedure on future pregnancy outcome. Obstet Gynecol 2005;2:325-332. |

|

Bruinsma FJ, Quinn MA. The risk of preterm birth following treatment for precancerous changes in the cervix: a systematic review and meta analysis. BJOG 2011;118:1031-41. |

|

Arbyn M et al; Perinatal mortality and other severe adverse pregnancy outcomes associated with treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: meta analysis BMJ 2008: 337; 1284 |

|

Kyrgiou, M et al. Proportion of cervical excision for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia as a predictor for pregnancy outcomes. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2015: 128(2): 141 |

|

Pfaendler KS, Mwanahamuntu MH, Sahasrabuddhe VV, Mudenda V, Stringer JSA, Parham GP. Management of cryotherapy-ineligible women in a “screen-and-treat” cervical cancer prevention program targeting HIV infected women in Zambia: Lessons from the field. Gynecol Oncol 2008;110:402-407. |

|

Lima MI, Tafuri A, Araujo AC, Miranda Lima L, Melo VH. Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia recurrence after conisation in HIV positive and HIV negative women. Int J Gynecol Obstet 2009;104:100-104. |

|

Figge DC, Creasman WT: Cryotherapy in the treatment of cervical neoplasia. Obstet Gynecol 62:353, 1983 |