Diagnosis and Management of Benign Breast Disease

Authors

INTRODUCTION

As an integral part of the female reproductive system, the breasts are within the purview of obstetrics and gynecology. Furthermore many, if not most, women will consult their obstetrician-gynecologist when they have breast symptoms or concerns. Also, most women have questions about breast cancer, mammography, and hormone therapy – either combined estrogen/progesterone or estrogen alone. Finally, a thorough breast examination is an essential component of a general physical or annual examination. Therefore, obstetrician-gynecologists should be able to diagnose and manage benign breast problems and make appropriate referrals when indicated. They should recommend, in addition, that all women aged 40 and older have annual screening mammography.

DEVELOPMENT, ANATOMY, AND PHYSIOLOGY OF THE FEMALE BREAST

The anatomy and histology of the female breasts are essentially the same as in the male until puberty. The development of the female breast (thelarche) usually begins approximately 3 years before the onset of menstruation (menarche). Commonly, thelarche begins at approximately age 11 and menarche at age 13. The breasts are usually fully developed by age 18. Multiple hormones (Table 1) act in balanced consort to mature the female breast and prepare for the physiologic function of lactation. Development of the breast stroma, growth of the ducts, and fat deposition are promoted primarily by estrogen. Lobular growth, alveolar budding, and alveolar secretory changes are promoted primarily by progesterone. However, the complete maturation of the ductal alveolar system requires both estrogen and progesterone acting in balanced consort.

During pregnancy, chorionic gonadotropin, placental lactogen, and prolactin stimulate the ductal alveolar system. Milk secretion and lactation require the consorted action of cortisol, growth hormone, oxytocin, parathyroid hormone, and thyroxine. Prolactin primarily regulates milk secretion and lactation after delivery.

Table 1. Essential hormones for female breast development

| Adrenal glucocorticoids |

| Estrogen |

| Growth hormone |

| Insulin |

| Progesterone |

| Prolactin |

Particularly during a menstrual cycle, the ductal and alveolar epithelial cells undergo replication and programmed physiologic cell death (apoptosis), although these processes are not uniform throughout the ductal alveolar systems. Ductal mitotic activity is reported to be prominent during the late luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, when progesterone is relatively dominant.1, 2

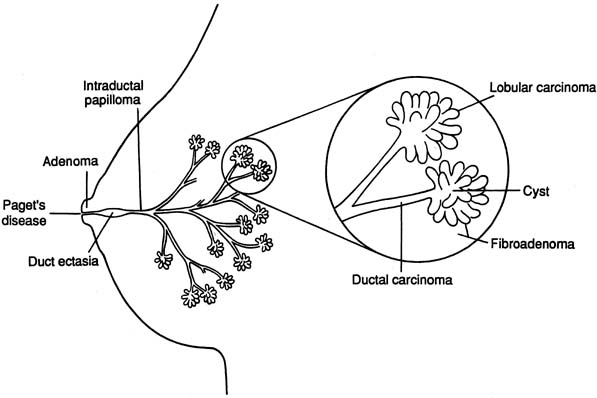

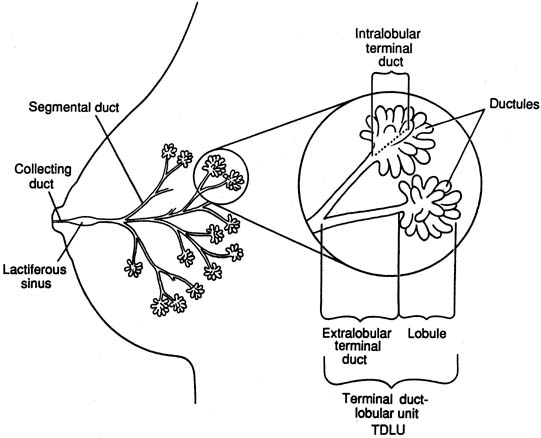

The diagrammatic representation of a single lobe and terminal duct lobular units is depicted in Figure 1. The common sites of breast pathology are depicted on a similar diagram in Figure 2. Although traditionally the breast is described as containing 12 to 15 distinct lobes, observation reveals that there are usually approximately six openings onto the nipple (galactophores), as some of the lobes join at the level of the collecting duct or even into the lactiferous sinus. Otherwise, there is no direct anatomical connection between the various lobes.

|

|

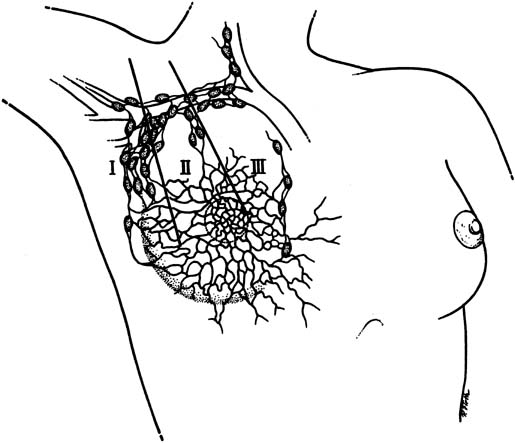

The lymphatic drainage of the breast is primarily to the axillary lymph nodes (Fig. 3), which are usually the initial site of detectable breast cancer metastases. In surgical anatomy, the axillary lymph nodes are described as: level I, lateral to the pectoralis minor muscle; level II, under the insertion of the pectoralis minor; and level III, medial to the pectoralis minor. In current surgical practice, axillary lymph node dissection for breast cancer calls for the removal of the level I and level II nodes.

|

The bulk of the breast is adipose tissue, regardless of the size of the breast. There is no correlation between breast size and breast cancer risk. The lobes develop in a random branching pattern similar to the spreading branches of a tree. Beginning approximately during the mid-20s, there is progressive diminution of the fibroglandular tissue in the breast and the adipose tissue becomes more prominent. Mammography becomes more effective as a woman's age advances because of the contrast of an abnormal mass to the surrounding adipose tissue.

Major developmental breast abnormalities (Table 2) are rare and do not respond to hormone therapy. If the patient or her mother insists on treatment, referral to a breast plastic surgeon is appropriate. Supernumerary nipples and ectopic breast tissue can occur along the embryologic milk line. The most common location is in the axillae.

Table 2. Congenital and developmental breast abnormalities

| Accessory axillary breast tissue: ectopic breast tissue, usually bilateral and often symptomatic with pregnancy |

| Amastia: absence of one or both breasts |

| Delayed thelarche: no breast development by age 15 |

| Macromastia (gigantomastia): grossly enlarged breasts occurring with pregnancy or drug-induced |

| Juvenile hypertrophy: excessively enlarged breasts, usually bilateral |

| Poland syndrome: absence of the breasts, pectoralis muscles, and shoulder girdle; upper limb malformations |

| Polymastia: supernumerary breast |

| Polythelia: supernumerary nipples |

| Symmastia: midline confluence or webbing |

Source: Adapted from Hindle and Pan,1 with permission.

BREAST-ORIENTED HISTORY

When a woman presents with breast symptoms or problems, in addition to the general medical history, a specific breast-oriented history should be taken and recorded. The essential components of a breast-oriented history are listed in Table 3. The location of the symptoms should be accurately diagramed in the record and carefully labeled right or left breast.

Table 3. Essential components of a breast-oriented hstory

| Her chief breast symptom |

| Her age |

| Date of her last menstrual period |

| A personal history of breast cancer |

| A family history of breast or ovarian cancer (especially a mother or sister) including the age at diagnosis |

Her age at menarche and first pregnancy Number of children and history of breast-feeding |

| Any breast surgery |

| Any trauma to her breast |

| The date and result of her last mammogram |

| Is she or has she been using oral contraceptive therapy, estrogen replacement therapy, hormone replacement therapy (estrogen + progesterone), tamoxifen, or raloxifene? |

CLINICAL BREAST EXAMINATION

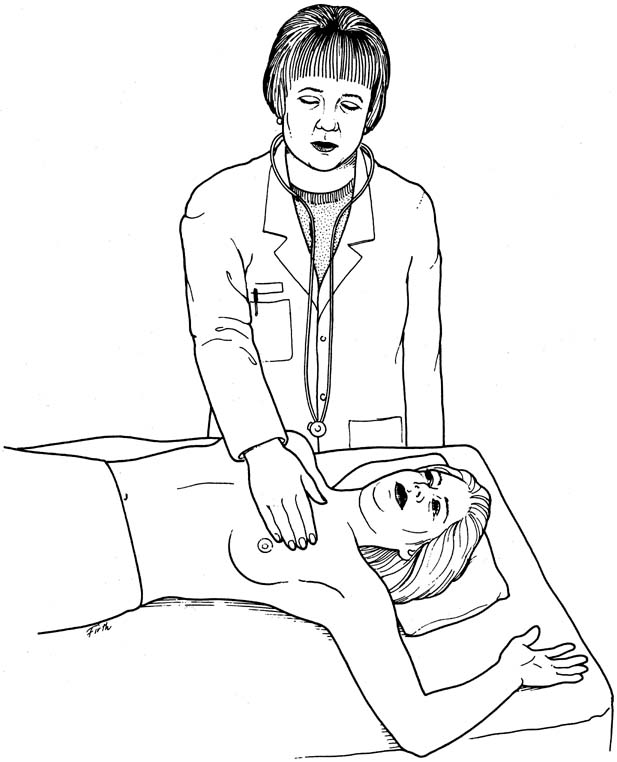

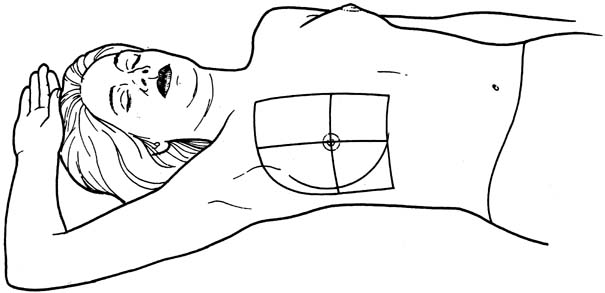

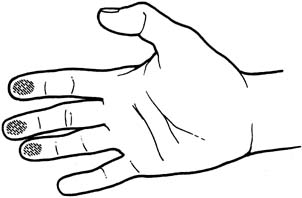

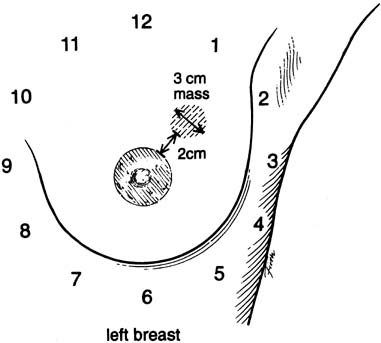

An effective technique of clinical breast examination is illustrated in Figures 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9. The paramount goal of clinical breast examination is to identify a palpable dominant mass, which by definition is a three-dimensional distinct mass that is different from the remainder of the breast tissue and from the tissue of the other breast. The location of a palpable dominant mass should be identified by its clock position and its distance (in centimeters) from the areolar edge, as illustrated in Figure 10. Ideally, the size of the mass should be recorded (measured in centimeters), as well as a description of the consistency of the mass (soft, firm, hard) and the characteristics of the borders (edges) of the mass (for example, distinct, smooth, irregular, indistinct). A dominant breast mass should be definitively diagnosed in a timely manner, even though a dominant mass in a premenopausal woman is most likely benign. A dominant mass in a postmenopausal woman is most likely malignant.

|

|

|

|

|

SCREENING AND DIAGNOSTIC BREAST IMAGING

Asymptomatic (for the breast) women aged 40 years and older should have annual screening mammography preferably using full-field digital mammography and computer-aided detection (CAD). This improves the effectiveness of perception of small nonpalpable malignancies that have the optimum prognosis; for example, more than 90% 10-year disease-free survival when treated.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8

Mammograms are reported in a format following the guidelines of Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS)9 mandated by the Mammography Quality Standards Act (MQSA) in 1992. The descriptive patterns of mammographic breast density are listed in Table 4. The mammographic assessment categories are listed in Table 5. The radiologist who reads the mammogram should be contacted directly if any part of the report, such as the descriptive patterns, the assessment categories, the mammographic diagnosis, and the specific recommendations, is not clear. A reliable systemic patient tracking and reminder system for mammograms, such as described in the ACOG Clinical Review in November 2002,10 should be established with written policies clearly documented and rigorously followed.

Table 4. The BI-RADS descriptive patterns of mammographic breast density

| The breast is almost entirely fat |

| There are scattered fibroglandular densities that could obscure a lesion on mammography |

| The breast tissue is heterogeneously dense; this may lower the sensitivity of mammography |

| The breast tissue is extremely dense, which lowers the sensitivity of mammography |

Table 5. The BI-RADS mammographic assessment categories

| Category 0 | Need additional imaging evaluation |

| Category 1 | Negative |

| Category 2 | Benign finding |

| Category 3 | Probably benign finding: short interval follow-up suggested |

| Category 4 | Suspicious abnormality: biopsy should be considered |

| Category 5 | Highly suggestive of malignancy: appropriate action should be taken |

Diagnostic breast imaging for a woman with breast symptoms or findings should be obtained if she is aged 35 or older. The imaging work-up usually begins with the same bilateral craniocaudal and mediolateral oblique views as those performed for screening mammography. Subsequently, additional views such as spot compression or magnification are often obtained. High resolution ultrasound is recommended for symptomatic women younger than 35 years. It is also recommended in women aged 35+ if they have mammographically dense breasts or suspicious mammographic or clinical abnormalities. Breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is increasingly being used for screening high-risk young women and facilitating the local staging of breast cancer, in particular, the evaluation of ipsilateral multicentric or multifocal lesions and synchronous contralateral disease which may be 'missed' by conventional imaging.11 Additional indications for breast MRI include monitoring the tumor's response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy, detection of local recurrence and the evaluation of breast prosthetic implants.

Generally, mammography for symptomatic women younger than 35 years of age is neither accurate nor cost-effective and rarely adds to the clinical management. However, if the clinical diagnosis is breast cancer, then mammography should be obtained for patients of any age.

FINE-NEEDLE ASPIRATION: TECHNIQUES, CYTOLOGY, AND PATHOLOGY

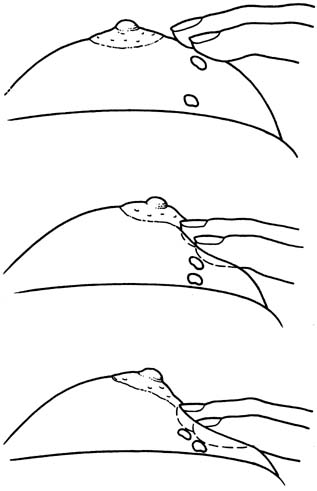

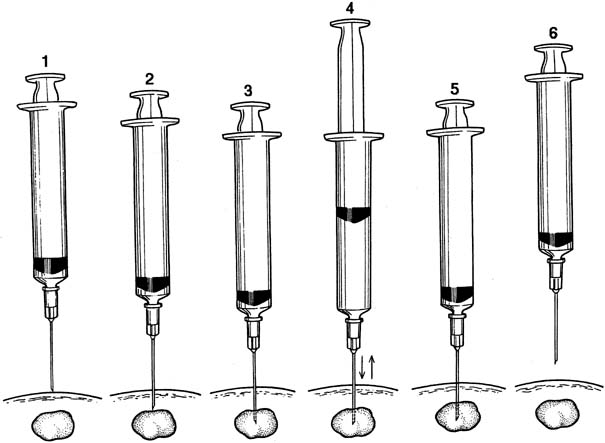

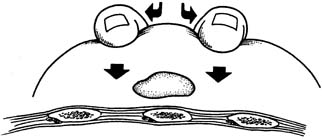

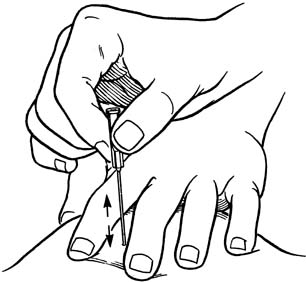

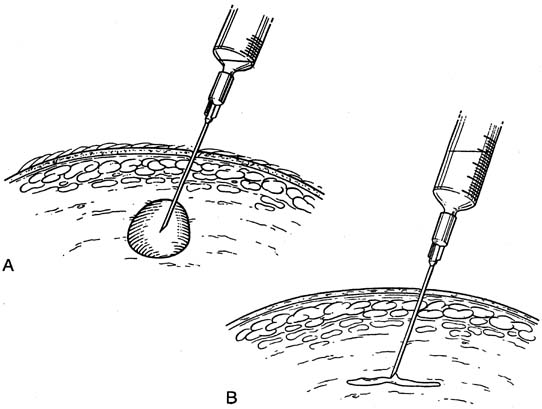

Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) of a palpable breast mass is a well-established diagnostic technique. Figure 11 illustrates FNA with a small handheld syringe holder, and Figure 12 shows the sequential steps of needle insertion and application of negative pressure within the syringe. Palpable cysts can be readily identified and therapeutically drained by FNA. With an adequate cell sample, an FNA cytologic diagnosis of a palpable solid breast mass can be obtained in as many as 90% of cases.12, 13

|

With appropriate instruction and training, breast FNA can be readily adapted to office practice, as illustrated in Figures 13 and 14. The use of liquid-based collection media and automated processing systems, for example, Thin Prep (CYTYC Corporation, Boxborough, MA), circumvents the need for a cytotechnician and the potential problems of on-site slide preparation. Various other effective FNA techniques have been described.12

Examples of the histology (low- and high-power) and the corresponding FNA cytology (low- and high-power) are presented in color plates 1 through 16 in Volume 1, chapter 26 for normal breast tissue, breast fibrocystic changes, fibroadenoma, and invasive ductal carcinoma.

BREAST BIOPSY

FNA provides cells for cytologic diagnosis; however, histological tissue diagnosis of palpable or radiological abnormalities can be achieved by core biopsy using automated devices. Vacuum-assisted core biopsy devices are increasingly being used to evaluate screen-detected microcalcifications and to therapeutically remove probable benign lesion. These devices can be used under stereotactic, ultrasound or MRI guidance14.

With the advent of percutaneous tissue sampling techniques, the traditional open surgical biopsy (incisional biopsy or lumpectomy) is rarely required nowadays in order to establish the histological diagnosis 15. Lumpectomy is usually used therapeutically to remove the whole lesions and the details of the procedure have been described elsewhere.16

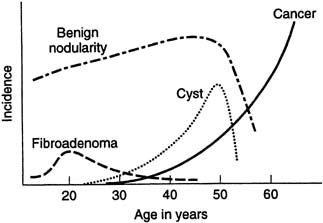

FIBROCYSTIC CHANGES

Histologic fibrocystic changes (see color plates 5–6) are probably present in the breasts of most women of reproductive age.22, 23, 24 Reproductive age can be defined as those years during which a woman is having regular menstruation; for example, ages 14–50. There is wide variation in the amount and severity of fibrocystic changes. Clinically, a confluence of fibrocystic changes can form a dominant palpable mass and require a specific histologic biopsy diagnosis.22 Such a confluence of fibrocystic changes is a common biopsy diagnosis during the reproductive years of woman's life but is rare after the menopause (Fig. 15) There is a vague correlation between the histologic presence of fibrocystic changes and the palpable diffuse nodularity that is commonly felt throughout the breasts of women of reproductive age, is often somewhat tender, and that may be associated with premenstrual mastalgia.22 Fibrocystic changes per se are not premalignant and are not associated with increased risk of breast cancer. The definitive diagnosis of fibrocystic changes is a histologic tissue diagnosis.

FIBROADENOMA

Fibroadenoma (see color plates 9–10) is the most common benign neoplasm of the breast and usually is diagnosed as a palpable mass (for example, 1–3 cm) in the early reproductive years of a woman's life (see Fig. 15), but it can be diagnosed at almost any age. The diagnosis is usually confirmed with ultrasound examination and FNA cytology or core biopsy.

By examination, a fibroadenoma is typically rubbery to firm, mobile, smooth with distinct borders, and is usually nontender. Fibroadenomas per se are not premalignant, but certain histologic changes within a fibroadenoma or in the surrounding stroma have been reported to be at low levels of increased breast cancer risk.25 When definitely diagnosed, fibroadenomas need not be removed, because they tend to to remain unchanged or decrease in size approaching the menopause and usually become nonpalpable after the menopause. However, some women prefer to have such breast lumps excised. This can be performed electively in the form of open lumpectomy or percutaneous vacuum-assisted core biopsy as an outpatient procedure under local anesthesia.

The uncommon phyllodes tumors resemble fibroadenomas in clinical presentation and cytology but are often larger (3–6 cm) and tend to occur in older women (35–45 years old) and tend to increase in size. The diagnosis requires histologic verification. Phyllodes tumors can be histologically benign, indeterminate, or malignant. The tumor should be excised with wide (1-cm), clear, surgical margins and carefully followed up. Metastasis is rare.

MASTALGIA

Mastalgia is a common breast symptom for women during their reproductive years.26 It is usually cyclic but can be noncyclic. The cyclic variant is usually diffuse and most intense during the immediate premenstrual phase of the cycle. Cyclic mastalgia is usually bilateral but can be unilateral. Noncyclic mastalgia is usually localized, often persistent, and less responsive to treatment than cyclic mastalgia. Clinically, it is imperative to be certain the pain is within the breast and not of a nonbreast etiology affecting the anterior chest wall (Table 6). Mastalgia is rarely associated with malignancy unless there is a palpable breast mass.

Table 6. Nonbreast etiologies of anterior chest wall pain

| Achalasia |

| Angina |

| Cervical radiculitis |

| Cholecystitis |

| Cholelithiasis |

| Coronary artery disease |

| Costochondritis (Tietze syndrome) |

| Fibromyositis |

| Hiatal hernia |

| Myalgia |

| Neuralgia |

| Osteomalacia |

| Phantom pain |

| Pleurisy |

| Psychological pain |

| Pulmonary embolus |

| Pulmonary infarct |

| Rib fracture |

| Sickle cell disease |

| Trauma |

| Tuberculosis |

Most women presenting with cyclic mastalgia have an intense variant of physiologic breast changes that occur during the menstrual cycle. After complete evaluation and examination including a mammogram for a woman aged 35 or older, the patient can be reassured that there is no evidence of cancer and that her symptoms are physiologic. European studies have demonstrated that as many as 85% of women presenting with cyclic mastalgia will accept this reassurance as satisfactory treatment and do not require pharmacologic therapy.27 There is a good level of evidence that simple measures such as the use of a well-fitting firm bra and regular exercise improve mastalgia.

Bromocriptine, evening primrose oil, and tamoxifen have been shown to be effective therapies for mastalgia in European studies.27 Favorable responses as high as 92% for cyclic and 64% for noncyclic mastalgia have been reported but sequential therapies may be required.27 Only danazol is Food and Drug Administration-approved (FDA-approved) for the treatment of mastalgia. The initial dose is 100 mg orally twice per day continued until the patient has symptomatic relief, and then the dose usually can be decreased and remain effective. Unfortunately, many women using danazol experience bothersome side-effects (such as hot flushes, weight gain, acne, amenorrhea, hirsutism, and deepening of the voice) and discontinue therapy. Topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory preparations have been also reported to be effective in relieving mastalgia. A breast pain chart for daily monitoring of the occurrence and intensity of the mastalgia before, during, and after treatment is useful in documenting the results of therapy.27

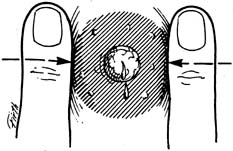

CYST

Palpable breast cysts (macrocysts) commonly occur during the late reproductive years of a woman's life (see Fig. 15). By examination, a macrocyst is typically palpable, clearly defined, soft, mobile, and smooth. The borders are distinct. Cysts are often somewhat tender, especially before menstruation. Many cysts may be multiple and/or bilateral. FNA is an effective and efficient method of diagnosing and treating a cyst in the office. As much fluid as possible should be aspired from the cyst (Fig. 16). Only grossly bloody fluid needs to be sent for cytologic evaluation. Cytology of nonbloody fluid is unrewarding and not cost-effective.28 However, after FNA, the area of the cyst must be palpated to be certain there is no residual mass, and the patient should be seen again in approximately 3 months to ascertain if the cyst has refilled.

Cysts per se are not premalignant. A benign intracystic papillary proliferation can occur within a cyst and is often associated with bloody cyst fluid. The rare intracystic carcinoma is clinically suspected when the fluid is grossly bloody, or there is a residual mass after aspiration. In cases of grossly bloody cyst fluid, the patient should be referred to a breast specialist for further invitigations and diagnostic histology. Ultrasound-guided core biopsy of any intra-cystic solid lesion or irregular cystic wall is recommended for histological diagnosis.

Microcysts are a component of breast fibrocystic changes. These nonpalpable cysts are essentially normal histologic findings. A microcyst is rarely symptomatic.

Cysts, both macro and micro, are perceived on mammograms as distinct masses with smooth regular borders. However, mammography does not differentiate a cyst from a solid mass. Ultrasound is effective in differentiating a cyst from a solid mass. A symptomatic cyst requires therapeutic FNA.

NIPPLE DISCHARGE

Nipple discharge, usually clear, yellow, and watery, can be elicited from the nipples of most women of reproductive age. This is physiologic. Persistent or recurrent spontaneous nipple discharge, particularly from a single duct is pathologic and should be evaluated. The most common etiology of spontaneous nipple discharge is an intraductal papilloma or papillomas. These are benign lesions. Nipple discharge is rarely a sign of malignancy unless there is an associated palpable mass and the discharge is grossly bloody. However, all intraductal lesions should be excised and histologically evaluated not to miss the rare intraductal carcinoma.

Figure 17 illustrates an effective method of eliciting nipple discharge. When the discharge appears, it is important to note and record the color, consistency, from how many ducts it appears, and whether it can be elicited bilaterally. With rare exceptions, nipple discharge related to a breast cancer is spontaneous, unilateral, from a single duct, and bloody. Furthermore, there is usually an associated mammographic or clinical abnormality.

Investigations of pathological nipple discharge include simple discharge cytology, mammography (aged 35 years or older), ultrasonography, MRI (in selected cases) and mammary ductoscopy29. Galactography (ductogram) which may be useful in identifying the intraductal pathology is rarely performed nowadays. Microdochectomy (surgical excision of the discharging duct) is usually required in order to establish the pathological cause and relieve the discharge. In this procedure, the surgeon inserts a small probe, for example, a lachrymal probe, at the time of the operation through the galactophore from which the discharge is coming. Thus, the spontaneous nipple discharge must be actively present for these procedures. The surgery usually can be performed as an outpatient procedure through a limited circumareolar incision using local anesthesia.

Paget's disease of the nipple (a variant of ductal carcinoma, intraductal, and/or invasive) can present as an erythematous weeping lesion on the surface of the nipple and the areola, although it usually presents as a dry, scaly, eczematous lesion. The patient may perceive this as nipple discharge. The diagnosis is made by histologic tissue biopsy (incisional or punch biopsy). There is often an underlying palpable mass or a radiological abnormality.

Galactorrhea (nonpregnancy-related milky nipple discharge) can be related to medications such as oral contraceptives, chlorpromazine, and psychotropics. However, an elevated thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) indicates hypothyroidism and a prolactin level more than 100 ng/ml indicates a pituitary microadenoma.

Mammary duct mastitis, also called ectasia, periductal mastitis, or plasma cell mastitis, usually presents as bilateral, thick, green discharge from multiple galactophores on the nipples of a perimenopausal woman. However, there is controversy as to whether these are separate diseases. These entities are not bacterial infections and do not respond to antibiotics. The condition is self-limited and is not associated with neoplasms, benign or malignant. Over time, the condition usually subsides, particularly after the menopause. If the patient insists on treatment, surgical excision or tying off all the ducts is the only effective treatment.

MASTITIS

Puerperal mastitis (pregnancy- or lactation-related) is not unusual and usually responds quickly to antibiotic therapy. A full course of antibiotics effective for Staphylococcus aureus (for example flucloxacillin 500 mg orally every 6 hours or augmentin 625 mg every 8 hours for 7 days) should be administered as soon as clinical signs of mastitis, such as fever, erythema, induration, tenderness, and swelling, begin. The patient should be examined every 3 days to be certain the infection is responding to therapy and that there is no evidence of abscess formation. If there is lack of response, the antibiotic should be changed (i.e., to azithromycin 500 mg orally the first day and then 250 mg orally daily for 5 days; cephalexin 500 mg orally every 6 hours for 7 days; or clindamycin 300 mg orally every 6 hours for 7 days.) For a penicillin-allergic patient, erythromycin 500 mg orally every 6 hours for 7 days is an alternative initial therapy. Breastfeeding should be continued if already begun and/or the infected breast can be pumped until the mastitis clears. Cultures are not rewarding.

A breast abscess presents as a flocculent sometimes-bulging mass usually located in the central area of the mastitis. Focused ultrasound can verify a fluid-filled (pus) center. Aspiration with a number 18-gauge needle using local anesthesia is diagnostic and can be therapeutic if all the pus is aspirated. The aspirate is sent for mocrobiological analysis. The aspiration may have to be repeated every 3 days, particularly if there is more than 10 milliliters of pus initially aspirated.30 If the repeated aspirations are not effective in clearing the abscess, then open surgical dependent drainage under general anesthesia is required. Antibiotics should be continued until all evidence of inflammation (cellulitis) has cleared.

Nonpuerperal mastitis is uncommon and even rare in postmenopausal women. S. aureus, Peptostreptococcus magnus, and/or Bacteroides fragilis are the usual bacterial pathogens.

Again, the patient should be re-examined every 3 days until the infection clears. Augmentin 625 mg orally every 8 hours for 7 days as initial therapy is usually effective. Alternately, cephalexin 500 mg orally every 6 hours for 7 days can be prescribed.

Chronic mastitis is uncommon and can be associated with a subareolar abscess. Periareolar fistulae can occur and should be surgically excised when the inflammation is quiescent. Staphylococcus coagulase-negative and Peptostreptococcus propionica are the usual pathogens. Flucloxacillin 500 mg orally every 6 hours and metronidazole 500 mg orally every 8 hours for 10 days is often effective because the pathogens are usually mixed aerobes and anaerobes.

With a case of mastitis that is unresponsive to antibiotic therapy and particularly if it seems to spread over the entire breast, inflammatory carcinoma should be considered and investigations should include breast imaging and a skin biopsy (i.e., punch biopsy) for possible diagnosis of carcinoma in the dermal lymphatics. As with other breast conditions, whenever the diagnosis remains undetermined and/or the condition persists despite what seems to be appropriate therapy, the patient should be expeditiously referred to a breast specialist.

OTHER UNCOMMMON BENIGN BREAST LESIONS

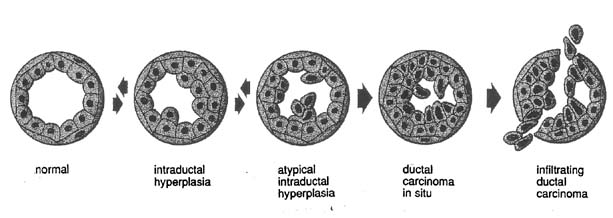

An adenolipoma usually presents as a smooth palpable mass and has a characteristic mammographic pattern. Apocrine metaplasia of the epithelial cells, which enlarge and are eosinophilic, are histologically noted in the lining of a cyst. Ductal hyperplasia is a benign histologic process, but when the hyperplasia is atypical it is associated with an increased risk of carcinoma and thought potentially to be the beginning of transformation to ductal carcinoma in situ and eventually invasive ductal carcinoma (Fig. 18). Fat necrosis can mimic cancer by examination but has a distinct mammographic appearance and is often secondary to breast trauma. Fat necrosis usually subsides spontaneously but may leave a residual mammographic lesion. A galactocele is a palpable milk-filled cyst most commonly associated with pregnancy or lactation. FNA can diagnose and drain a galactocele. A lactating (lactational) adenoma histologically resembles a tubular adenoma but the presence of milk is a prominent feature. Lactating adenomas are pregnancy- and/or lactation-related. A lipoma has a thin smooth border on mammography, can be palpable, and reveals only adipose cells by FNA or adipose tissue by biopsy. Lobular hyperplasia is a histologic diagnosis and may progress to lobular neoplasia with the potential of transformation to malignancy; for example, lobular carcinoma in situ. Mondor's disease is phlebitis and subsequent clot formation in the superficial (skin) veins of the breast. Typically, Mondor's disease presents as a firm, vertical, cord-like structure usually associated with a history of trauma to the breast; for example, surgery. The lesion usually resolves spontaneously in 8–12 weeks. A tubular adenoma presents similarly to a fibroadenoma both by examination and mammography. Histologically, the glandular elements predominate over the stromal elements that are contrary to fibroadenoma histology.

SUMMARY

As the primary health care providers for women, particularly during their reproductive years, obstetrician-gynecologists are in a unique position to evaluate and advise their patients with breast symptoms, findings, and concerns. Most benign breast conditions can be diagnosed and managed in a straightforward manner by obstetrician-gynecologists.

REFERENCES

Anderson TJ, Ferguson DJ, Rabb GM: Cell turnover in the “resting” human breast: Influence of parity, contraceptive pill, age and laterality. Br J Cancer 46:376-382, 1982 |

|

Ferguson DJ, Anderson TJ: Morphological evaluation of cell turnover in relation to menstrual cycle in the “resting” human breast. Br J Cancer 44:177-181, 1981 |

|

Tabar L, Chen H-H, Duffy SW et al: A novel method for prediction of long-term outcome of women with T1a, T1b, and 10-14 mm invasive breast cancers: A prospective study. Lancet 355:429-433, 2000 |

|

Pisano ED, Gatsonis C, Hendrick E et al. Diagnostic performance of digital versus film mammography for breast-cancer screening. N Engl J Med 353(17):1773-83, 2005 |

|

Joensuu H, Pylkkanen L, Toikkanan S: Late mortality from pT1N0M0 breast carcinoma. Cancer 85:2183-2189, 1999 |

|

Lopez MJ, Smart CR: Twenty-year follow-up of minimal breast cancer from the breast cancer detection demonstration project. Surg Oncol Clin North Am 6:393-401, 1997 |

|

Arnesson LG, Smeds S, Fagerberg G: Recurrence-free survival in patients with small breast cancer. Eur J Surg 160:271-276, 1994 |

|

Rosen PP, Groshen S, Kinne DW: Survival and prognostic factors in node-negative breast cancer; results of long-term follow-up studies. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 11:159-162, 1992 |

|

American College of Radiology (ACR): Illustrated Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADStm), 3rd edn. Reston, VA: American College of Radiology, 1998 |

|

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists: ACOG Clinical Review. Patient Safety Series: Tracking and Reminder Systems. pp 1-3, Vol. 7. Issue 9. Washington, DC, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2002 |

|

Patani N, Mokbel K. The utility of MRI for the screening and staging of breast cancer. Int J Clin Pract 62(3):450-3, 2008 |

|

Kline TS: Handbook of Fine-needle Aspiration Biopsy Cytology. pp 114-175. St Louis, MO, Mosby, 1981 |

|

Florentine B, Felix JC: Fine-needle aspiration cytology of the breast. In: Hindle WH, (ed): Breast Care. New York, Springer-Verlag, 1999 |

|

Liberman L. Percutaneous image-guided core breast biopsy. Radiol Clin North Am 40(3):483-500, vi. Review, 2002 |

|

Vargas HI, Vargas MP, Gonzalez K, Burla M, Khalkhali I. Percutaneous excisional biopsy of palpable breast masses under ultrasound visualization. Breast J 12(5 Suppl 2):S218-22, 2006 |

|

Arona AJ: Excision of a palpable breast mass in private primary care practice. In: Hindle WH, (ed): Breast Care. New York, Springer-Verlag, 1999 |

|

Margolin FR, Leung JW, Jacobs RP: Percutaneous imaging-guided core breast biopsy: 5 years' experience in a community hospital. AJR Am J Roentgenol 177:559-564, 2001 |

|

Duncan JL III, Cederbom GJ, Champaign JL et al: Benign diagnosis by image-guided core-needle breast biopsy. Am Surg 66:5-10, 2000 |

|

Skinner KA, Dunnington G: Surgery for breast cancer. In: Hindle WH. (ed): Breast Care. pp 206-208, New York, Springer-Verlag, 1999 |

|

Vazquez M, Waisman J: Needle biopsy. In: Rose DF, (ed): Breast Cancer, pp 230-238. Philadelphia, PA, Churchill Livingstone, 1999 |

|

Parker SH, Klaus AJ, McWey PJ et al: Sonographically guided directional vacuum-assisted breast biopsy using a handheld device. AJR Am J Roentgenol 177:405-408, 2001 |

|

Hindle WH: Fibrocystic changes. In: Hindle WH, (ed): Breast Care. New York, Springer-Verlag, 1999 |

|

Marchant DJ. Benign breast disease. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 29(1):1-20, 2002, Review |

|

Kramer WM, Rush BF: Mammary duct proliferation in the elderly: a histopathologic study. Cancer 31:130, 1973 |

|

Dupont WD, Page DL, Parl FF et al: Long-term risk of breast cancer in women with fibroadenoma. N Engl J Med 331:10-15, 1994 |

|

Arona AJ: Mastalgia. In: Hindle WH, (ed): Breast Care. New York, Springer-Verlag, 1999 |

|

Gumm R, Cunnick GH, Mokbel K. Evidence for the management of mastalgia. Curr Med Res Opin 20(5):681-684, Review, 2004 |

|

Hindle WH, Arias RD, Florentine B et al: Lack of utility in clinical practice of cytologic examination of nonbloody cyst fluid from palpable breast cysts. Am J Obstet Gynecol 182:1300-1305, 2000 |

|

Escobar PF, Crowe JP, Matsunaga T, Mokbel K.The clinical applications of mammary ductoscopy. Am J Surg 191(2):211-15, 2006, Review |

|

Eryilmaz R, Sahin M, Hakan Tekelioglu M, Daldal E. Management of lactational breast abscesses. Breast 14(5):375-9, 2005 |