Dyspareunia and Vaginismus

Authors

INTRODUCTION

The patient who experiences pain during intercourse provides a unique challenge to the physician practicing obstetrics and gynecology. There are many facets of this problem that challenge the specialist's skills in diagnosis, medical and surgical therapy, and interpersonal relationships. To assess this symptom, the physician engages in a unique process of self-examination. Positive attitudes toward sexual pleasure and coital function and an awareness of the role these two factors play in mental health and spousal relationships are necessary to facilitate complete exploration of this symptom.

Female dyspareunia is the most common sexual symptom presenting to the gynecologist. For many gynecologists, any report of pain prompts a diligent search for a surgically treatable cause of the symptom. However, the investigation of dyspareunia requires a more eclectic approach that includes special knowledge of female sexual functioning, a comfortable attitude toward discussion of sexual matters, and other special skills. The physician must have a complete understanding of sexual physiology to evaluate the adequacy of pelvic vasocongestion, vaginal lubrication, and the morphologic changes of the vagina during female sexual response. The physician must feel comfortable in asking sexually explicit questions that both acknowledge the legitimacy of the patient's sexual concern and encourage self-disclosure. Other skills include the ability (and time) to listen to the patient, encourage her to talk about her feelings, and help her understand the interaction among feelings, relationships, and physical function.

TERMINOLOGY

The term dyspareunia, as used in this chapter, refers to female coital pain, which includes recurrent or persistent discomfort associated with attempts at or during coitus. The term has been defined in a variety of ways over time and in different countries. It has been used to describe a lack of simultaneous orgasm, anorgasmia, or any coital pain caused by an organic lesion. The original Greek term dyspareunia means bad or difficult mating. However, a more appropriate Greek term would be algopareunia from the Greek work algo, which means pain.

The term vaginismus was originally used in 1862 by Dr Marion Sims to describe a reflex-like contraction of the circumvaginal musculature resulting in nonconsummation of marriage.1 More recently, vaginismus has been described as an involuntary spasm of the pelvic floor muscles and perineal muscles that surround the outer third of the vagina, which makes intercourse uncomfortable or impossible. This involuntary spastic contraction is a reflex response that is stimulated by imagined, anticipated, or real attempts at vaginal penetration.2 In severe cases of vaginismus, the abductors of the thighs, the rectus abdominus, and the gluteus muscles also may be involved. Vaginismus is a true psychosomatic entity.

In the past, some authors have attempted to dichotomize organic and psychogenic causes of dyspareunia.3 The term dyspareunia has been used to indicate coital pain with organic cause, while vaginismus encompasses painful coitus without organic cause. More recently, however, the emphasis in the literature has been focused on the need to integrate psychogenic and organic investigations (Fig. 1).

The term apareunia is used to describe the inability to experience vaginal containment of the penis. It can be either primary, as in an unconsummated relationship, or secondary (e.g. after a traumatic vaginal tear). Dyspareunia also can be primary or secondary, situational, or complete. Primary dyspareunia indicates that vaginal containment of the penis has been experienced, but coitus has always been accompanied by pain. Secondary dyspareunia suggests that before the onset of the presenting symptoms, comfortable coitus has occurred. In some women, difficult or painful coitus occurs in certain situations, and in others it may always be present.

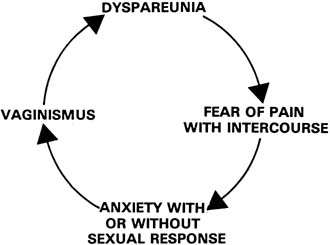

Vaginismus can be primary, secondary (see Fig. 1), situational, or complete. In primary vaginismus there is an involuntary muscle spasm at the introitus that begins with the first attempt to insert something in the vagina. Secondary vaginismus can occur because of a real or imagined painful experience on insertion of something into the vagina that results in muscle spasm. Situational vaginismus is a specific type of vaginismus related to a specific situation, such as coitus, but in this case the woman has no difficulty with gynecologic examinations or tampon insertion. Complete vaginismus refers to perineal spasms at every attempt to insert anything into the vagina including tampons, fingers, speculum, or penis.

ETIOLOGY

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) states that sexual trauma, negative attitudes towards sex, and youth are etiologic or associated features of vaginismus.4

Other factors reported include physical abuse, sexual ignorance, lack of differentiation, and relationship difficulties.5, 6, 7

One study confirms that a history of sexual trauma and less positive attitudes about sexuality were more commonly reported in the vaginismus group compared with women with vulvar vestibulitis and those in a no pain group.6, 7

In developing a biopsychosocial profile of women with dyspareunia, the vulvar vestibulitis subtype was associated with the highest levels of sexual impairment but not the higher level of psychologic symptoms compared to controls. The subtype with no discernible physical findings reported levels of sexual function comparable to controls despite elevated psychologic symptomatology and relationship dysfunction.7

These findings support other authors who invite us to reconsider our traditional approach to identifying and treating dyspareunia and vaginismus as a sexual dysfunction and approach it as a pain syndrome.8 Binik and colleagues report that "superficial dyspareunia" cannot be differentiated reliably from vaginismus.9

Pelvic floor muscle spasm is the defining physical finding on digital examination that is diagnostic of vaginismus. Binik states that "the available empiric evidence does not support this definition". He argues that the diagnosis of vaginismus and dyspareunia "be collapsed into a single entity, called genitopelvic pain/penetration disorder".10

Most sexual medicine physicians would argue that despite the lack of empiric evidence, superficial dyspareunia and/or vaginismus CAN be easily diagnosed with a careful history, visual examination, Q-tip test, and a one-finger vaginal examination. Vulvar dermatoses, and vestibulitis, for example, can be identified as causes of superficial dyspareunia in the absence of any pelvic floor spasm. On the other hand, digital examination of the pelvic floor muscles can identify and reproduce the pain of vaginismus as a primary source of pain or confirm the pain as secondary to the dermatoses or vestibulitis.

Farmer and Meston report that "Women with genital pain reported greater rates of sexual dysfunction compared to pain free women", and that women in the high pain group were distinguished from the low pain group by the amount of vaginal lubrication (arousal?).11 "For pain free women, intercourse played a strong role in sexual satisfaction, whereas non-intercourse sexual behavior was central to sexual satisfaction in women who reported pain." This report certainly confirms the observation of women with vulvodynia/vulvar vestibulitis syndrome (VVS) and secondary vaginismus.

INCIDENCE

Most women who are coitally active will experience dyspareunia at some time in their lives. Recurring painful intercourse results in repeated disappointment, sexual frustration, and dissatisfaction, and eventually to the loss of self-esteem, feelings of resentment or rejection from the partner, and a loss of intimacy in the relationship. Semmens and Semmens12 reported on 500 women between the ages of 18 and 60 who consecutively attended a private outpatient gynecologic clinic. Two hundred women (40%) identified pain with coitus as a major symptom, although they had attended the clinic to seek routine care. Only 4% of the patients cited dyspareunia as their chief symptom. In a community survey of middle-aged women,13 33% admitted to sexual dysfunction. Of the total population, 8% acknowledged the presence of dyspareunia, and a further 17% acknowledged vaginal dryness. In a study of 51 Dutch gynecologists,14 data revealed that 7.2% of their patients had a problem or concern that was sexually related. The most common problem seen in the week before the survey was dyspareunia. A third survey of 887 gynecologic outpatients seen consecutively revealed a 19% prevalence of sexual symptoms.15 The most common sexual symptom was dyspareunia (48%). Another study of prevalence of dyspareunia suggests that of 313 respondents to a questionnaire on sexual experience and dyspareunia, 39% had never had dyspareunia, 27.5% had had dyspareunia that resolved, and 33.5% had dyspareunia for some time and still had it at the time of the survey.16 A study at the Cleveland Clinic of aspects of sexual function related to uterovaginal prolapse and urinary incontinence reported a prevalence of vaginal dryness and dyspareunia in 41% of the sexually active women.17 They found no association between vaginal anatomy and vulvovaginal atrophy with sexual function, including dyspareunia and vaginal dryness. A questionnaire was administered to women in five primary care settings in North Carolina. Of the 549 respondents, 44% said they experienced dyspareunia during intercourse, and 27% experienced pain after intercourse.18

The incidence of vaginismus is much more difficult to estimate. In a study of 230 women who experienced dyspareunia, vaginismus was observed during pelvic assessment in more than 50% of them.19 Vaginismus has been reported to be the cause of 84% of unconsummated marriages.20 Thirty years ago, one gynecologist found that 4–5% of married women in his practice had an intact hymen several months into the marriage.21 The incidence of primary vaginismus is estimated to be 1–2%.

In clinic populations, secondary vaginismus is by far more common finding and often accounts for over 50% of women with coital pain.22

PSYCHOPHYSIOLOGIC FACTORS

An understanding of female physiologic sexual response and the psychophysiology of sexual dysfunction is essential to assess and manage problems of dyspareunia and vaginismus. The first sign of sexual excitement in a woman is the production of a clear transudate through the wall of the vagina,2 which is known as vaginal lubrication. As the term indicates, this substance provides lubrication for penile thrusting, which decreases the friction between the penis and vaginal mucosa. Without the production of this transudate, the friction of the penis on the dry vaginal wall can lead to irritation, burning, and pain. The second component of the female sexual response is the morphologic change of the vaginal barrel during the plateau phase of sexual arousal. The inner two thirds of the vaginal barrel balloon out while the outer one third forms the orgasmic platform. The ballooning or tenting of the vagina increases the circumference and length of the vagina to better accommodate the penis during coitus. The final psychophysiologic function requiring assessment is that of the pelvic floor and perineal muscles. The edge of the levator ani or pubococcygeus muscle impinges on the lateral wall of the vagina approximately 1.5–2 inches above the hymen. Patients characteristically describe the involuntary spasm of these muscles during attempts at insertion of the penis as hitting a brick wall just inside the vagina. It should be remembered that vaginismus is a clinical condition assessed through history and physical examination. The etiology is often unclear to the patient, her partner, and the physician. The etiology can vary from relatively simple (embarrassment and inhibition) to complex (struggles with differentiation, individuation, and past abuse).23 All of these issues need to be considered during the patient's assessment.

GENERAL ASSESSMENT

Many patients with symptoms of vaginismus and dyspareunia are seen for gynecologic consultation. It is important that the consultant recognize that this is a couple problem. Although much can be accomplished in an office consultation with the woman alone, the true impact of the symptom or symptoms cannot be assessed without an assessment of the couple. Similarly, the division of couple therapy into either relationship or sexual is artificial and anachronistic.24 The split between viewing this symptom as an individual problem or a couple problem is anachronistic because it represents our traditional approach to treating gynecologic symptoms as purely somatic symptoms. Similarly, the split between relationship therapy and sexual therapy is anachronistic because it is representative of the alienation that has existed throughout the Western world between sexuality and personality in an individual.

Proper assessment of these problems begins with a problem-based approach to history taking and includes a review of the onset and evolution of the problem to its present state. This review will help determine the impact of the problem on the patient and her partner, both functioning as individuals, and as a couple. The problem-solving approach highlights the couple's intellect, insight, and motivation. A review of the evolution of the problem will identify the timing of events and their effect on the patient's sexual response and will uncover other attempts at therapy.

The general principles of assessment include reviews of both individual and relationship factors, both sexual and nonsexual. For example, it is important to determine the extent to which a young woman's dyspareunia is a function of her performance anxiety with her partner or to what extent it is indicative of a general lack of sexual comfort and competence. Primary vaginismus, resulting in nonconsummation, may be the one method of birth control in which this woman has faith, a functional dysfunction as it were. Similarly, a woman with the symptoms of vaginismus may be locked in a struggle for control with her partner, making treatment of the presenting symptom pointless unless the relationship problem is resolved.

During the assessment, the physician needs to make a distinction between a sexual or relationship factor and a problem as identified or experienced by the patient or her partner. For example, during assessment, a woman with vaginismus may be found to have an inhibition about touching her own genitals. This is a factor neither she nor her partner perceived to be related in any way to the presenting problem. During the assessment, the therapist must help the couple discover connections between the two. Two final questions in the general assessment include: (1) who owns the problem? and (2) what is the couple's motivation for treatment?

Individual assessment

Individual factors that require some consideration and assessment include intrapersonal, sexual socialization, gender role socialization, and biologic factors (Table 1). While all physicians will not have the skills of an experienced dynamically oriented psychotherapist in assessing intrapersonal factors, it is important that they have some ability to understand and assess these factors.

Table 1. Individual factors in the assessment of dyspareunia and vaginismus

| Intrapersonal |

| Autonomy |

| Competence |

| Self-esteem |

| Comfort with affect |

| Mental status |

| Sexual socialization |

| Knowledge |

| Attitudes toward sexual and sensual pleasure |

| Gender role socialization |

| Biologic |

| Organic disease (direct) |

| Organic disease (indirect) |

| Treatment of organic disease |

The intrapersonal factors to be assessed are autonomy, competence, self-esteem, comfort with affect, and mental status. A truly autonomous adult can function separately both from her partner and from her parents. A sense of competence refers to the subjective side of one's actual competence and refers to one's inner sense of mastery. A patient's self-esteem would include a sense of competence and a perception of being loved and cherished. Comfort with affect refers to the ability to discriminate among internal affective states, to label them appropriately, and to express them in words that lead to open, honest, interpersonal communication. Assessment of mental status would include the detection of gross abnormalities in mental functioning, such as organic brain disease, severe mood disorder, weight loss, abnormally elated or depressed affect, or psychosis.

Sexual socialization requires an assessment of the vertical factors operating in the family that include “all the family's attitudes, taboos, expectations, labels, and loaded issues with which people grow up.”24 These institutionalized forces in society work largely through the family to help shape adult behavior. The two factors requiring assessment in the area of sexual socialization include: (1) sexual knowledge and myths; and (2) attitudes toward sensual and sexual pleasure. It is evident that many people live and grow in an environment of sexual ignorance. In the absence of adequate and systematic sex education, children invent their own explanations for biologic and sexual processes, often in the form of mythologies. In addition, in contemporary society, myths are generated by the authoritarian pronatalist sex code, sometimes disguised as psychological concepts. Myths of vaginal orgasm and simultaneous coital orgasm are just two examples of myths promoted as goals of normal sexual functioning. Attitudes toward sensual and sexual pleasure emphasize coital performance and de-emphasize the value of general body pleasure.

Gender role socialization refers to a person's learned or cultural status or one's sense of self as male or female. It includes the collective body of attitudes and behaviors that a culture considers appropriate for males or females.

Biologic factors include any organic disorder that directly affects the endocrine, vascular, and neurologic components of human sexual response. Dermatologic conditions can affect the epithelium of the vulva, vestibule, and vagina, causing painful lesions (provoked or unprovoked).

These ulcers and erosions of the genital tract can be caused by infections, such as Candida or herpes, or can be dermatoses such as lichen sclerosus, lichen planus, Becet's, aphthosis, or contact dermatitis. All of these erosions and ulcers can cause pain with coital contact (dyspareunia) or result in pain from anticipatory vaginismus. Secondarily, biologic factors can affect sexual function indirectly, or the treatment of an organic problem itself may affect the expression of sexuality. For example, surgical procedures can directly affect the nerve supply to the pelvis, or they can indirectly affect sexual function through an altered body image, with loss of self-esteem to the point at which a woman no longer sees herself as a sexually attractive individual. A large number of drugs have shown to affect sexual appetite, and they function either by central mechanisms or by a direct effect on the neurologic and vascular components of the genital response.

Couple assessment

The interaction among relationship and sexual factors in the production of problems in a couple is complex (Table 2). Relationship factors include an assessment of the level of communication, the ability to negotiate, and the degree of mutual support. These factors can be viewed in terms of interpersonal skills, which can be taught and learned. Assessment of these factors will identify skill deficits, and therapy will possibly help couples correct them to ensure continued symptomatic relief of the dyspareunia or vaginismus.

Table 2. Couple factors in the assessment of dyspareunia and vaginismus

| Relationship factors | Sexual factors |

| Communication | Function |

| Negotiation | Range of behaviors |

| Support | Satisfaction |

| Experience with reproduction |

Sexual factors in the assessment include function, range of behaviors, and satisfaction as well as plans and experiences with reproduction.

Although this assessment may appear to be long and complex, an experienced physician interested in sexual symptoms can assess these factors in a relatively short time and obtain the necessary information on which to base a rational approach to therapy.

Pelvic assessment

Assessing dyspareunia is not complete until a pelvic examination has been performed. Relaxation is the key factor in a successful genital examination, both for the patient and the doctor. It is likely that most women undergoing pelvic examination feel that this experience is an involuntary intrusion into their lives and bodies. Although the patient intellectually consents to her examination to benefit from a complete assessment, at best, her emotional consent is ambivalent; at worst, her emotional consent is fearful and revulsive. The physician's ability to make the patient comfortable and demonstrate a high level of clinical skill helps to generate a sense of relaxation. A vital factor in a successful pelvic examination is an acknowledgment of the patient's vulnerability in the power relationship between the physician and the patient.25 If the doctor is unaware, insensitive, or unwilling to acknowledge the patient's vulnerability in this relationship, the examination will not be an educational opportunity and much clinical data will be lost.

A careful pelvic examination allows the physician to assess physiologic and pathologic factors on the spot. Visual, colposcopic, speculum, bimanual, and rectovaginal examination provide a detailed assessment of the genital tract and pelvis and provide an opportunity to confirm the source of the patient's pain. The cotton swab test of vulva or vagina allows focused exploration to identify an exact source of discomfort. Through the use of a hand mirror and diagrams, the physician can help the patient to be better-informed about her anatomy and physiology and generate the concept of a three-dimensional view of her pelvis. A digital examination will clarify the possible role of vaginismus in dyspareunia and, if present, allow for an assessment of the degree of vaginismus (Table 3).26

Table 3. Classification of degrees of vaginismus

| Classification and degree | No. of patients (n = 80) |

| First degree: perineal and levator spasm – relieved with reassurance | 27 |

| Second degree: perineal spasm – maintained throughout pelvis | 21 |

| Third degree: levator spasm and elevation of buttocks | 18 |

| Fourth degree: levator and perineal spasm, elevation; adduction and retreat | 10 |

| Refused examination | 04 |

If both the individual and the couple assessment strongly suggest a physical cause of the dyspareunia, the patient may be enlisted in self-examination to help identify a specific source of pain. A sexologic examination is useful in patients who have sexual concerns and understand the goals of this examination. This examination is performed on a patient, with or without her partner present, to assess the health of the genital tract and provide an educational opportunity for the patient regarding the genitals, their function, and the nature of her problem. The patient's participation in the examination is encouraged to capitalize on this educational experience to help clarify the location, or source, of the pain and to observe the patient's reaction to, and interest in, her own body.

SUMMARY OF ASSESSMENT

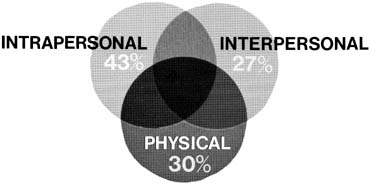

During the assessment of dyspareunia, the primary goal is to identify the underlying cause of pain. The assessment enables the physician to identify intrapersonal (interpsychic), interpersonal (relationship), or physical problems in each patient. Often the etiology is not limited entirely to one category (Fig. 2); an intrapersonal problem can precipitate an interpersonal problem, and a relationship problem can create intrapersonal concerns. Likewise, a physical problem can adversely affect the relationship or may be coincidental to an intrapersonal problem. Cases are classified according to the most obvious or primary source of the problem. In each case, the treatment strategy is designed to alleviate the coital discomfort. Each patient and her partner, if involved, can be given detailed information regarding the nature of the problem, assurance that the problem can be solved, and an outline of possible therapeutic approaches.

In intrapersonal problems, the presenting symptom is seen primarily as being within the patient herself. The assessment often uncovers certain factors, such as fear, trauma, ignorance, anxiety, lack of sexual emancipation, and a belief that sexual intercourse is for reproduction only, that impact on the physical problem.

In interpersonal problems an assessment of the couple's relationship may identify a conflict that is directly related to the presenting symptom of painful intercourse. Painful intercourse may be caused by major conflicts in the areas of family size, contraception, relationship priorities, sexual frequency, sexual timing, sexual techniques, and sexual boredom. These relationships are often characterized by poor communication in general and particular difficulty in talking about sex and about feelings. Struggle for control can be an issue, and the woman may feel that she can only control the sexual relationship to some degree. There may be pressure on sexual performance, especially when coitus is the primary or sole source of sexual pleasure and coital orgasm is a necessity for one or both partners.

The spouse in these relationships is often described in disparaging terms by the patient herself. Terms such as passive, indifferent, uncooperative, irresponsible, unfaithful, inadequate, or physically unappealing are sometimes used.

Physical problems are usually identified by reviewing individual and couple factors and then confirmed by the physical examination. The physical problems can be a primary cause of dyspareunia, or contribute to interpersonal or intrapersonal problems. Table 4 summarizes these factors, which were presented in an early article that reviewed 230 patients with dyspareunia who had been assessed. The four major categories in this table include trauma, atrophy, inflammation, and obstruction-fixation. Three physical problems that require special mention are pelvic congestion-varicosities,27 vulvadynia,28 and residual ovarian syndrome.29 All these problems are ill-defined, difficult to diagnose, and difficult to treat adequately. Pelvic congestion-varicosities are being identified more often with transvaginal ultrasound with the patient in the sitting position, or pelvic venogram. Some centers are now treating persistent pain by embolizing veins greater than 1 cm in diameter. Prospective studies are not yet available to assess this approach. Vulvodynia and vulvar vestibulitis are common problems seen in colposcopy and vulvar pain clinics. Multiple therapies have reported excellent initial results, but follow-up studies have not been reassuring. Sexual problems and vaginismus are a common feature in most of these women.12 The prime difficulty in assessing these conditions relates to the subjective nature of pain in isolation from intrapersonal and interpersonal issues. These conditions sometimes come full-circle to the interface between a psychic and somatic problem when, in fact, in an individual patient it may represent a functional dysfunction.

At present, we are seeing women more frequently with complaints of painful intercourse after vaginal prolapse surgery where non-absorbable suture or mesh/graft material is used, leading to an increase in erosion, granulation and pain with intercourse. This pain may lead to secondary vaginismus and aparunia. A systematic review of 110 studies from the literature (1950–2010) reports an erosion rate of 10.3%. Dyspareunia was reported at 9.1% (70 studies). The incidence of secondary vaginismus was not reported.30

Estrogen therapy may improve sexual function in postmenopausal women in a number of ways. Local use of estrogen in the vagina is safe and effective in restoring elasticity and vaginal pH, and in improving blood supply and lubrication. Oral estrogen was reported to increase clitoral sensitivity, desire, and rates of orgasm.31

Table 4. Summary of primary and secondary problems

| Primary physical problem | No. | Secondary problems (No.) |

| Trauma | 19 | 2 |

| Episiotomy | 10 | |

| Vaginal tears | 8 | |

| Vaginal septum | 1 | |

| Atrophy | 19 | 3 |

| Postmenopausal/surgical castration | 14 | |

| Radiation | 2 | |

| Neovagina | 1 | |

| Vulvar dystrophies | 2 | |

| Inflammation | 10 | 2 |

| Vulvitis/vaginitis | 8 | |

| Urethritis and caruncle | 1 | |

| Pessary | 1 | |

| Obstruction-fixation | 20 | |

| Constipation | 5 | 1 |

| Retroversion and congestion | 9 | 6 |

| Endometriosis | 3 | 3 |

| Prolapse | 1 | |

| Adhesions | 1 | 5* |

| Intact hymen | 1 |

*Tender adnexa – no diagnosis

TREATMENT

Therapeutic approaches are determined by the outcome of the individual, couple, and physical assessment of dyspareunia. The pelvic examination is necessary to confirm the suspicions raised by the historical assessment. Specific assessment of the introitus is necessary to confirm the presence and degree of vaginismus.

The therapeutic process may have started, in fact, with the patient acknowledging her problem. Often the couple has engaged in a meaningful discussion before the consultation that has facilitated the decision to seek help. Certainly, by the end of the complete assessment of the problem, a therapeutic relationship has been established, motivation has been assessed, and a contract negotiated between the patient, or couple, and the physician.

The first step in therapy is education regarding the nature of the problem and assurance that the problem can be solved. The use of diagrams, a hand mirror, and the educational pelvic examination ensure the patient's understanding of her symptom and its underlying problems.

Individual therapy may be indicated to assist the woman in dealing with intrapsychic issues and to determine whether she prefers individual help and whether her partner is indifferent or uninvolved.

Treatment of primary vaginismus requires some special considerations. If procreation is the primary goal of therapy, self-insemination in the privacy of the couple's home is an effective procedure. Conception and vaginal birth can occur in women with severe penetration phobia who have not had intercourse experience.32

The choice of therapy needs to relate to the woman's level of differentiation. “Differentiation, functioning autonomously with emotional and physical maturity, is vital to women who want and yet physically cannot allow vaginal penetration.”23 Addressing this issue in individual therapy may be necessary before cognitive-behavior techniques, to ensure sustained success.

Interpersonal problems are resolved best with short-term structured communication or sexual counseling that focuses on those interpersonal issues identified during the assessment. Referral for long-term relationship therapy may be indicated when the physician cannot negotiate a specific contract with the couple that is directed at resolving the presenting symptom.

Behavior therapy techniques are particularly useful in dealing with patients who have dyspareunia or vaginismus related to intrapsychic or couple problems. Short-term therapy focuses on reversing the symptoms. Intrapsychic issues that interfere with physiologic sexual response or create vaginismus, based on inhibition, fear, or trauma, respond best to this approach. Insight-oriented therapy attempts to change emotions over a period of time that leads to change in behavior. Short-term behavioral techniques result in behavior change that over time leads to a change of feelings.

Behavior therapy involving 1-hour weekly sessions with the therapist focusing on a series of graduated exercises aimed at systematic desensitization to vaginal insertion. The patient, or couple, performs the home play three to four times between visits. A range of interventions may be used, including deep muscle relaxation, progressive sexual fantasies, physical and verbal communication, and pleasuring exercises to achieve comfort with this approach. Specifically, Kegel exercises are used to acquaint the patient with voluntary control of her levator muscles. Insertion of the patient's fingers during the exercise provides her with an immediate biofeedback of contraction and relaxation of this muscle. When the patient can conduct this exercise successfully and comfortably insert two or three of her own fingers in the vagina, she advances to the next step.

The final step in this process is experiencing vaginal containment of the penis in the female-above position in which the woman is in complete control of inserting the penis into the vagina. When vaginal containment has been experienced with comfort, therapy then focuses on the gradual inclusion of sexual responsiveness and a variety of coital positions. During this therapy, it may be useful to separate the relaxation–levator exercise from conjoint sessions that are directed at sensual and sexual pleasure. Prohibiting attempts at coitus or partner finger insertion during the relaxation–levator exercises are important to allow the woman to relax with her partner.

Other therapies that may be used in treating the patient with dyspareunia include diagnostic procedures, such as laparoscopy to assess the pelvic viscera, injection of a long-acting local anesthetic in a vaginal scar as a diagnostic test for further surgical treatment, or the use of medications such as anesthetic creams, estrogen cream, or antihistamines for vaginal or vulvar pruritus, burning, and discomfort.

Physical problems require specific physical treatments. They may include simple changes such as laxatives or a high-fiber diet for hard stool in the pelvis, antibiotics for urethral syndrome or cystitis, or instructions on using the knee–chest position for a retroverted uterus and pelvic congestion.

The newest treatment proposed for vaginismus is the use of Botox injections into the pelvic floor muscle. First reported in 1997, this treatment is now being offered by plastic surgeons and other physicians throughout the world. Bertolasi and colleagues used botulinum neurotoxin A and successfully treated secondary vaginismus (to vestibulodynia).31 Pacik reports success treating primary vaginismus with Botox and bupivicaine intravaginal injections.33

The basic principles of treatment of dyspareunia are simple and straightforward. A proper assessment of a population of patients with this symptom requires careful consideration of intrapsychic and relationship factors as well as a physical assessment. The basic principles of treating the underlying problem can be imparted to the patient and her partner during history-taking and physical examination. Putting the patient in control is an important factor both in achieving an adequate assessment of her problem and in establishing a successful therapeutic approach.

The importance of involving the partner in the assessment at some point will produce an important ally for the therapist. A partner who is informed and involved will facilitate treatment no matter what the underlying etiology.

Understanding and treating physical problems is greatly enhanced by a knowledge of sexual physiology, psychophysiology, and clinical medicine. Careful evaluation can uncover certain underlying problems, and specific physical or psychologic therapeutic approaches are necessary to correct these problems.

REFERENCES

Sims J: Vaginismus. Trans Obstet Soc London 356-367, 1862 |

|

Masters WH, Johnson VE: Human Sexual Inadequacy. Boston, Little, Brown & Co., 1970 |

|

Harlow RA, McClusky CJ: Introital dyspareunia. Clin Med 27:1972 |

|

American Psychological Association ( 1994 ): Diagnostic and Statistical Manuel of Mental Disorders (4th Edition ), Washington, D.C. |

|

Silverstein JL, Origins of Psychogenic Vaginismus : Psychotherapy Psychosom 1989;52:197-204. |

|

Reissing ED, Binik YM, Khalife S, et al.Etiological Correlates of Vaginismus: Sexual and Physical Abuse, Sexual Knowledge, Sexual Self Esteem, & Relationship Adjustment.J of SEX & Marital Therapy 29: 74-79 |

|

Meena M, Binik YM, Kalife S, Cohen DR: Biopsychosocial Profile of Women With Dyspareunia. Obstet Gynecol 1997, 185 (9): 583-589. |

|

Meena M, Binik YM, Kalife S, Cohen DR:Dyspareunia:Sexual Dysfunction or Pain Syndrome? J New Ment Dis 1997,185 (9) 561-659 |

|

Binik YM. The DSM diagnostic criteria for dyspareunia.Arch.Sex. Behav. 2010;39(2) 292-303. |

|

Binik YM.The DSM diagnostic criteria for vaginismus. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2010;39(2) 278-291. |

|

Farmer MA, Meston CM:Predictors of Genital Pain in Young Women. Arch.Sex. Behav.(2007) 38:831-843. |

|

Semmens JP, Semmens JF: Dyspareunia: Brief guide to office counseling. Med Aspects Hum Sexuality 8:85, 1974 |

|

Osborn M, Hawton K, Gath D: Sexual dysfunction among middle-aged women in the community. Br Med J 296:959, 1988 |

|

Frenhen J, Van Tol P: Sexual problems in gynecological practice. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol 6:143, 1987 |

|

Backman GA, Leiblum SR, Grill J: Brief sexual inquiry in gynecologic practice. Obstet Gynecol 73:425, 1989 |

|

Glatt AE, Zinner SH, McCormack WM: The prevalence of Dyspareunia. Obstet Gynecol 75:433-436, 1990 |

|

Weber AM, Walters MD, Schover LR et al: Vaginal anatomy and sexual function. Obstet Gynecol 86:946-949, 1995 |

|

Jamieson DJ, Steege JF: The prevalence of dymenorrhea, dyspareunia, pelvic pain, and irritable bowel syndrome in primary care practices. Obstet Gynecol 87:55-58, 1996 |

|

Lamont JA: Female dyspareunia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 136:282, 1980 |

|

Blazer JA: Married virgins: A study of unconsummated marriages. J Marriage Fam 26:213, 1964 |

|

Green-Armytage VB: Dyspareunia. Br Med J 1:1238, 1956 |

|

Crowly T,Richardson D,Goldmeier D: Recommendations for the Management of Vaginismus:International Journal of STD and AIDS 2006: 17: 14-18. |

|

Shaw J: Treatment of primary vaginismus: a new perspective. J Sex Marital Ther 20:46-55, 1994 |

|

Watters WW et al: An assessment approach to couples with sexual problems. Can J Psychiatry 30:2, 1985 |

|

Basson R: Lifelong vaginismus: A clinical study of 60 consecutive cases. J SOGC 551-561, 1996 |

|

Lamont JA: Vaginismus. Am J Obstet Gynecol 131:632, 1978 |

|

Teoh G:Deep Dyspareunia.Aust Fam Physician 9:345 1980 |

|

Turner MLC, Marinoff SC:Association of Human Papilloma Virus with Vulvodynia and the vulvar vestibulitis syndrome. J Reprod Med 33:533, 1988 |

|

Bukovsky I et al: Ovarian Residual Syndrome.Surg Gynecol Obstet 167:132, 1988. |

|

Abed H, Rahn DD, Lowenstein L, Balk EM,Clemons JL, Rogers RG: Incidence and management of graft erosion, wound granulation, and dyspareunia following vaginal prolapse repair with graft materials: a systematic review.Int. Urogynecol. J 2011;22 (7) 789-98. |

|

Bertolasi L, Frasson E, Cappelletti JY et al. Botulinum neurotoxin A injections for vaginismus secondary to vulvar vestibulitis syndrome. Obstet Gynecol 114: 1008- 1016 |

|

Drenth JJ, Andriessen S, Heringa MP et al: Connections between primary vaginismus and procreation: Some observations from clinical practice. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol 17:195-201, 1996 |

|

Pacik P. Vaginismus: Review of Current Concepts and Treatment Using Botox Injections, Bupivicaine Injections, and Progressive Dilation with the Patient Under Anaesthesia. |