Evaluation and Management of the Infertile Couple

Authors

INTRODUCTION

Fertility in men and women is regulated by a series of tightly coordinated and synchronized interactions within the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis. The operational characteristics of the reproductive axis leave little room for error. Reproductive tract structures are also at risk for the development of diseases that render them unfit or compromised in their primary role of reproduction. Disorders at any level of the system may lead to involuntary infertility, which affects approximately 15% to 20% of couples or approximately 11 million reproductive-age people in the United States. Infertility therapy has been evaluated carefully in the last decade as new medical and assisted reproductive techniques have gained widespread approval. Advancements in the basic science of gamete physiology, conception, and implantation have also added greatly to our knowledge base, while at the same time have introducing a number of controversies in the treatment of infertile couples.

Primary infertility occurs in couples with no previous history of conception. Secondary infertility exists when a prior conception has been, at a minimum, documented by a positive human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), histology, or ultrasound. The causes of infertility are equally distributed between males and females and often the physician encounters multiple etiologies during the investigation. Most infertile couples have one or more of three major causes: a male factor, ovulatory dysfunction, or tubal-peritoneal disease.

As both men and women delay childbearing, an emerging disorder is being recognized, that of the aging gamete. As women enter the last decade of their reproductive capacity, anovulation, spontaneous abortions, and decreased fertilization are much more common. The overall quality of the oocyte is diminished and genetic errors are more common. In addition, there may be an increased incidence of endometriosis and uterine pathology such as leiomyoma, intrauterine adhesions, and adenomyosis with advancing age. Because of the epidemic of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) such as chlamydia and gonorrhea, pelvic infection may lead to tubal occlusion, pelvic adhesions, and distortion of tubal-ovarian anatomy. Also, because of increased use of and availability of contraception and abortion, fewer infants are available for adoption. These factors place more demands on the physicians who treat infertile couples to provide a more accurate, thorough, and rapid evaluation and treatment.

Infertility evaluation and treatment is often expensive. Each year infertile couples spend an estimated $1 billion in pursuit of pregnancy. Unfortunately, many major insurance carriers exclude infertility as a reimbursable diagnosis. Therefore, the financial burden is often left with the infertile couple. One must take these issues into consideration when counseling patients about treatment options available to them. Evaluation of fertility issues may be extremely stressful to some married couples. Loss of privacy, disruption of spontaneous sexual habits, and a feeling of reproductive failure or inadequacy are frequent causes of depression, anxiety, and grief in these patients. The practitioner must be aware of the psychological impact of infertility, and be sensitive and understanding to the patient’s needs. Referral for counseling or to local infertility support groups may be helpful.

The infertility evaluation serves to: (1) determine the etiology(ies) of infertility as expediently as possible, (2) provide the couple with recommended treatment protocols, (3) determine expected success rates and approximate costs for recommended therapy, and (4) educate the couple about their specific disorder and available alternatives. A certain percentage of patients are merely seeking diagnosis and do not intend to pursue therapy or cannot afford recommended diagnostic tests or treatment. Some couples proceed with adoption, while others comply with specific medical and/or surgical therapy.

GENERAL PRINCIPALS

Definitions

Infertility is defined as the inability of a couple practicing frequent intercourse and not using contraception to fail to conceive a child within 1 year. This definition is based on investigations by Tietze and colleagues1 who reported in 1950 that 90% of 1727 couples followed for 1 year became pregnant. The probability of conception depends on the length of exposure, coital frequency, and the age of the couple. In normal, young couples the chances of conception after 1 month of unprotected intercourse is 25%; 70% by 6 months, and 90% by 1 year. Only an additional 5% will conceive after waiting an additional 6 to 12 months.2 Once fertility therapy is initiated, couples must be counseled that a given period of time is required to test the adequacy for any given treatment regimen.

A thorough evaluation of the infertile couple often reveals one or more causes for failure to conceive. Motivated couples that comply with therapeutic guidelines can expect a 50% to 60% chance of conception. A spontaneous, treatment-independent cumulative pregnancy rate of about 30% to 40% exists in couples in which no identifiable cause for the infertility can be determined.

Age Factors

With more women pursuing careers and delaying childbearing, infertility is becoming an increasing problem in our society. The peak rate of conception occurs in both men and women in the mid-20s. A consistent decline in fecundity after 30 to 35 years of age has been demonstrated, with an incidence of involuntary infertility in women at the age of 40 ranging from approximately 33% to 64%. Reduction in age-related fertility is predominantly the result of the decline in oocyte quality, enhanced follicular atresia, and an increased rate of chromosomal abnormalities in fertilized oocytes and resulting embryos. These ovarian effects are associated with a rise in basal follicle-stimulating hormone levels, indicative of reduced ovarian reserve. With decreasing frequency of intercourse, the per-cycle probability of conception also declines. Thus, in the couple over 30 who meets the definition of either primary or secondary infertility, the work-up should be initiated and completed as soon as possible (Table 1).

TABLE 1. Expected Percentage of Nonsterile Currently Married Women Who Will Conceive Within 12 Months of Unprotected Intercourse

Age Group | Conceiving in 12 months(%) |

20–24 | 86 |

25–29 | 78 |

30–34 | 63 |

35–39 | 52 |

Adapted from Hendershot GE, Mosher WD, Pratt WF: Infertility and age: An unresolved issue. Fam Plann Perspect 14:287, 1982.

Causes of Infertility

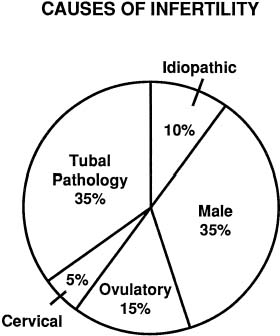

The exact incidence of the various etiologic factors for infertility appears to vary with the population studied. In the broadest of terms, 15% to 20% of the causes of infertility are the result of ovulatory dysfunction; 30% to 40% are caused by pelvic factors such as endometriosis, adhesions, or tubal disease; 30% to 40% are because of male factors such as oligospermia, increased semen viscosity, decreased sperm motility, or decreased semen volume; less than 5% are because of abnormal sperm-cervical mucous penetration or anti-sperm antibodies. In approximately 10% to 15% of couples no direct cause of their infertility can be found, but on further evaluation and treatment, occasionally factors such as poor sperm penetration, abnormal-appearing oocytes, etc., are elucidated. This group is referred to as unexplained infertility (Fig. 1).3

The etiology of infertility varies among races and economic strata. A recent study indicated that while the leading diagnosis of infertility in Caucasian patients is ovarian in origin (46.5%) followed by male factor (24.5%), the leading diagnosis of infertility in the African American population was tubal (41%) followed by surgical sterilization (25.6%). Also, patients without insurance were more likely to be surgically sterilized than those patients with insurance regardless of race or marital status.4

Given the growing incidence of infertility, it should become routine practice for physicians and educators to educate females about their lifestyle choices and how they may affect their reproductive capacity. For instance, early education that STDs may decrease future fertility may motivate some women to practice more abstinence or use condoms and spermicide. Additionally, anorexia, bulimia, and obesity result in ovulatory dysfunction and infertility. The first-line treatment for these diseases and their associated infertility is weight adjustment. Furthermore, couples should realize the effects of aging on reproduction. This knowledge will empower couples to make more informed decisions regarding childbearing. Finally, caffeine and smoking have all been associated with decreased fertility.5 Cigarette smoking in particular has been associated with an adverse affect on ovarian function and also on implantation. Furthermore, smoking may impair the uterotubal motility, thus increasing the risk for ectopic pregnancy in smokers.6 It is the role of all primary care physicians to educate patients on these risks from a young age, so that they may make responsible decisions. A more thorough list of causes of infertility is listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2. Causes of Infertility

Male | Female |

Disturbed spermatogenesis | Congenital anomalies |

| Acute/chronic illness | Vaginal |

Exposure | Uterine |

Chemicals | Fallopian tubes |

Recreational Drugs | Sexual dysfunction |

Heat | Endocrine disorders |

Radiation | Ovary |

Genital disorders | Adrenal |

Genital injuries | Thyroid |

Endocrine disorders | Pituitary |

Varicocele | Hypothalamus |

Insemination disturbances | Sequelae of pelvic infections and inflammation |

Genital anomalies | Pelvic adhesions |

Genital trauma | Endometriosis |

Genital surgery | Tubal occlusion/phimosis |

Pelvic surgery | IUD complications |

Sexual dysfunction | Postsurgical |

Spinal cord injuries | Oophorectomy/cystectomy |

Veneral diseases | Myomectomy |

Abnormal seminal fluid/cervical mucus | Conization of cervix |

interaction | Pregnancy complications |

Infections | Abortion |

Immunologic | Cesarean section |

Intrinsic spermatozoal defects | Postpartum infections |

Unknown | Ectopic pregnancy |

Abnormal sperm/egg interaction | Immunologic |

Infection | Serum/cervical mucus antisperm antibodies |

Immunologic | Inadequate cervical secretions |

Intrinsic spermatozoal defects | Drug effects |

Unknown | Postsurgical |

Unexplained (?) | Unexplained (?) |

IUD, intrauterine device.

Evaluation of the Couple as a Unit

Infertility should be regarded as a two-patient disorder. Male and female partners must be thoroughly evaluated, counseled, and included in the therapeutic decision-making processes. Exclusion of the male partner may lead to feelings of isolation in the female and to disinterest and lack of cooperation of the male partner. A questionnaire is often helpful prior to the first visit and should include questions regarding prior conceptions, contraception, and coital frequency and techniques. This document serves as a basis for review and in-depth questioning and does not replace the history. Both partners should be screened for the use of drugs or alcohol that may affect fertility. Studies in males with heavy marijuana use show reduced testosterone levels, decreased sperm counts, and impotency.7 Alcohol is well known to affect libido and potency as well. Decreases in gonadotropin levels and ovulation are noted in females with frequent drug or alcohol ingestion. Cigarette smoking has also been implicated in subfertility. Early menopause, reduced spermatogenesis and decreased steroid production have been noted in individuals who use cigarettes. Life-tablele analysis studies demonstrate a longer period of time to conception for smokers as compared to nonsmokers.

Quality and Availability of Services

The ideal environment for care of the infertile couple would involve almost total dedication of a clinical setting to attend to the needs of the infertile couple. Physicians and ancillary staff should be specifically oriented to respond appropriately to the sometimes unrealistic expectations and profound emotional stresses experienced by couples with infertility problems. The nurse-clinician often provides the crucial link between the couple and the medical staff, thus making harmonious an evaluation that is often viewed by the couple as constituting personal invasion and physical trauma.

Infertility services may be offered either through clinic-like settings associated with large institutions or via the services of private practitioners. Clinic services may be viewed as involving too many physicians and fellows in training. A rotational schedule of physicians for ovulation induction or assisted reproductive technology (ART) may be seen as precluding the development of an appropriate relationship with the responsible physician. Also, participation in randomized clinical trials, the backbone of scientific clinical research, may be seen as cold and impersonal. On the other hand, private care can be fragmented when the infertile patient is seen amidst 20 to 30 obstetrical and gynecologic cases. In such an environment, infertility assumes a relatively unimportant position and patient experiences are often negative. Great care and an appropriate commitment to the infertile couple are vital to success in both settings.

Because of the unique needs of the infertile patients, the coordination of medical care must be well organized in either setting. Achievement of this goal can be extremely difficult. The seemingly endless frustrations and patient demands are influenced to some degree by the increasing specialization of fertility services, as well as the incessant exposure of consumers to multiple negative and positive opinions via the media or through episodic contact with various medical services. Nurses and coordinators of fertility services must be more sensitive and knowledgeable than usual. They must continually be involved in education designed to broaden their appreciation for the medical and emotional aspects of fertility disorders.

INITIAL CONSULTATION

The initial workup of the infertile couple consists of a semen analysis, detection of ovulatory function by various methods, and evaluation of tubal patency by hysterosalpingogram (HSG) with concomitant fluoroscopy. Further evaluation of pelvic anatomy, either by laparoscopy and/or hysteroscopy may be considered as a part of the initial workup if there is an abnormality on HSG or later if no cause for infertility can be found. Purely diagnostic laparoscopy for the infertile woman is being used less frequently as more couples are advanced on the ART earlier in the evaluation. Other procedures such as Y chromosome mapping, anti-sperm antibodies, sperm penetration assay (SPA), or other tests of sperm function may be used in certain cases.

Complete Medical and Gynecologic History

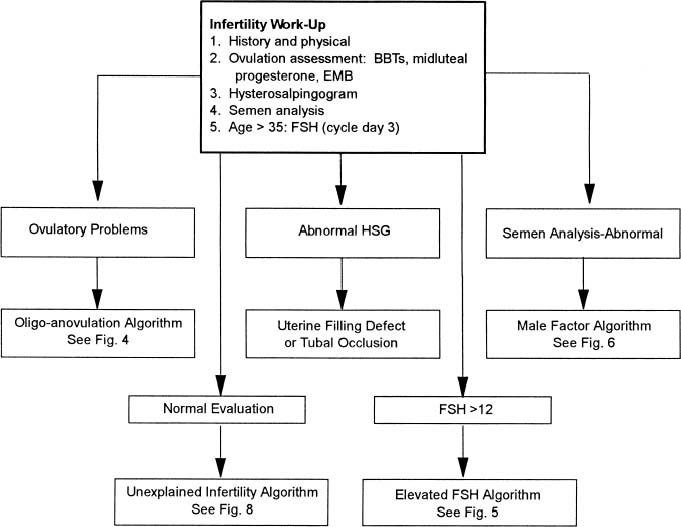

The basic evaluation of an infertile couple is generally agreed on (Fig. 2) The evaluation consists of a detailed history, physical examination, assessment of ovulation, semen evaluation, as well as uterotubal assessment. In addition, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), and estradiol levels obtained on the third day of the menstrual cycle maybe useful in women older than 35.

FEMALE.

A thorough workup is based on an extensive history and physical examination. The woman should be asked about the timing of her pubertal development and menarche. Menstrual history should include cycle length, duration, and amount of bleeding, associated dysmenorrhea, or premenstrual symptoms. A history of spontaneous, regular, cyclic predictable menses is, in almost all women, consistent with ovulation, while a history of amenorrhea or abnormal or unpredictable bleeding suggests anovulation or uterine pathology. Previous pregnancies, abortions, and birth control history are also documented. The patient should be asked about dyspareunia or severe dysmenorrhea that may be linked to endometriosis. A history of pelvic inflammatory disease, STD, ruptured appendix or other abdominal surgery, and the past use of an intrauterine device may be associated with tubal disease. A history of galactorrhea may be an indication of elevated prolactin levels, while a history of pubertal onset of progressive hirsutism associated with oligomenorrhea may indicate polycystic ovarian disease or other disorders of androgen excess. Excessive weight loss or weight gain, excessive stress or exercise is often associated with ovulatory disorders. Sexual, social, and psychological issues should be explored. Any prior infertility evaluation, surgery, or medical therapy is essential information and records, films, or surgical photographs should be sought and carefully re-evaluated.

MALE.

The male partner should be questioned about prior fertility, general health, medications, genital surgery, trauma, infection, and impotence. A history of drug or alcohol abuse, frequent hot-tub baths, excess stress, fatigue, or excessive or infrequent coitus should be elicited. Medical conditions that may result in infertility include diabetes (retrograde ejaculation), any serious debilitating disease, adult mumps orchitis, or pituitary hypofunction all may lead to hypogonadism. Herniorrhaphy, varicocele, and bladder neck suspensions are surgical procedures that may potentially be associated with infertility.

Careful Review of Records

Many infertile couples have had some prior evaluation for causes of their infertility and this information should be carefully reviewed. Couples may not understand the complexity of a thorough infertility evaluation. Many times the prior infertility evaluation was satisfactory by standards set 20 or 30 years ago, but is far from adequate by today’s standards. In addition, review of the couples’ records and reports may suggest a different interpretation. For instance, the woman who is proven to be ovulatory may have a cycle length of 25 days with a biphasic rise of basal body temperature, but the temperature elevation only lasts 7 to 11 days, which indicates a short luteal phase. An HSG that was reported as normal, may be of such poor quality that it cannot adequately rule out uterine filling defects or evaluate tubal patency. In addition, it is not uncommon to see couples who have experienced an extensive female evaluation and have undergone treatment for 5 or 6 years, but have not had a semen analysis or one repeated during that time.

Therefore, previous HSGs should be obtained and films reviewed. If previous pelvic surgery has been performed, operative notes, photographs, or videotapes should be obtained and reviewed. Hormonal studies including thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), FSH, luteinizing hormone (LH), progesterone, and prolactin should be evaluated based on the day within the menstrual cycle the sample was collected. Prior treatment regimens should be evaluated as to efficacy and length of treatment. All medications used by the couple should also be reviewed.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Female

A thorough general physical examination is necessary to help define factors that may lead to infertility. Special attention to signs of endocrine disturbance such as abnormal size or consistency of the thyroid gland, skin pigmentation, or the presence of abdominal stria should be documented. The presence of acne, oily skin, and hirsutism indicates androgen excess. Acanthosis nigricans, the presence of galactorrhea, surgical scars, or significant variation from normal body weight or percent body fat should be noted. The degree of estrogenization of the vagina and the quality and quantity of cervical mucus should be observed in the context of the current phase of the menstrual cycle. The presence of vaginal or cervical infection should be evaluated by microscopic examination of a wet preparation of a vaginal smear. The cervix is also carefully examined for anatomic abnormalities resulting from intrauterine exposure to diethylstilbestrol or prior cervical surgery, including cryotherapy, cautery, or laser. Cervical cultures for gonococcus, chlamydia, and Pap smears should be obtained. A thorough pelvic examination should detect the presence of cervical, uterine, adnexal tenderness, and pelvic masses. The size and contour of the uterus and adnexa should also be described. A careful rectovaginal examination may be performed to palpate uterosacral nodularity found in endometriosis. The length and direction of uterine cavity should be gently measured with a sterile plastic catheter to check for cervical stenosis as well as depth and direction of the uterine cavity. This information may aid in future intrauterine inseminations or embryo transfers.

Male

Physical examination of the male can be performed by the gynecologist, urologist, or family physician. The examination should focus on the degree of secondary sexual development, general body habitus, height, arm span, and presence of gynecomastia. A general physical examination is performed and should include evaluation of perineal sensation and rectal sphincter tone. Examination of the male genitals begins with careful inspection of the penis. Size and location of the urethral meatus as well as any discharge or evidence of stricture is evaluated. The testes are individually palpated and the relative weights, sizes, and consistency should be evaluated. The average volume for an adult testis is 25 mL or approximately 5 × 3 cm. Very small or soft testes are usually associated with a decrease in germinal tissue mass due to either testicular failure or some abnormality in the hypothalamic-pituitary axis leading to hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. The epididymis is palpated along its course to evaluate for swelling or tenderness consistent with epididymitis. The vas deferens should be evaluated by palpation. The presence of a varicocele should be looked for following valsalva. The prostate should be evaluated for size and evidence of prostatitis.

After the history and physical examination of both partners has been completed, an initial diagnosis should be made. The history and physical examination may clearly point to one or more etiologies. During the first evaluation initial laboratory and diagnostic tests should be ordered.

INITIAL LABORATORY AND DIAGNOSTIC TESTS-FEMALE

Basic Laboratory Testing

While routine preobstetrical screening of infertile women is not mandatory, it is extremely helpful to screen for patients for anemia and blood type, including Rh or antibody status. Women may need Rhogam after early spontaneous abortions or ectopic pregnancies. Women with a negative titer for rubella will require immunization prior to therapy for infertility. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing is essential in high-risk populations, those undergoing ART, or those receiving cryopreserved gametes. Some physicians screen all patients, with appropriate patient consent, yet the widespread screening for HIV in low-risk women has not been shown to be cost effective. Current guidelines for pregnant women in populations at high risk for cystic fibrosis are to offer testing for carrier status. Some fertility practices are beginning to test all egg donors for cystic fibrosis, and offer screening to patients who are seeking treatment for infertility.

Ovulation Documentation

Ovulatory factors account for up to 25% of infertility and may be caused by a multitude of factors that may be elicited in the initial history. This includes a history compatible with polycystic ovarian disease, oligomenorrhea, or amenorrhea associated with weight loss or excessive obesity, exercise, eating disorders, and galactorrhea. If the woman is experiencing cyclic menses, adequate ovulation and follicle development should be assessed by a number of methods in multiple cycles. Basal body temperature charting, sonographic follicle monitoring, urinary LH testing, midluteal progesterone levels, and endometrial biopsy as well as the clomiphene challenge test are important tests to evaluate ovulation and subsequent corpus luteum function.

BASAL BODY TEMPERATURE CHART.

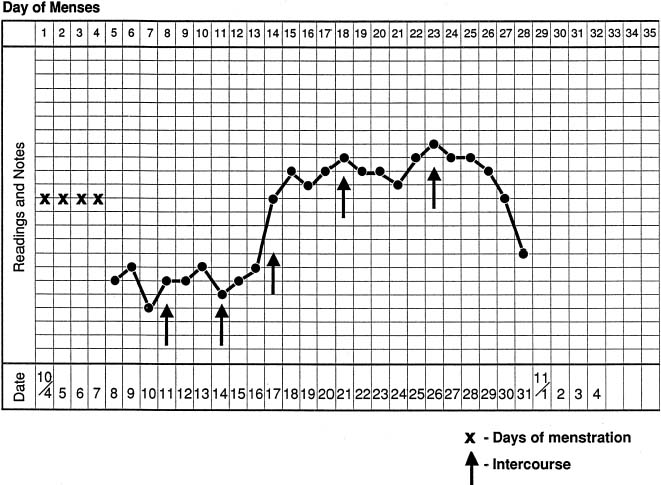

The basal body temperature chart, although much maligned, is still a useful and cost-effective index of evaluating ovulation. A biphasic temperature chart characterized by a sustained increased temperature of at least 0.4°F for 12 to 15 days is consistent with ovulation and an adequate luteal phase length (Fig. 3). The day of ovulation is usually the suggested by day of the lowest temperature (nadir) and is followed by a sustained rise in temperature of 0.4°F. However, significant variation in temperature may occur and it may be difficult to predict the time or the presence of ovulation in some cycles. Luteal phase length less than 11 days, as measured by basal body temperature chart recording, correlates well with luteal phase defects. This diagnosed can then be made by endometrial biopsy. Finally, the temperature chart serves as a visual reminder for the couple and physician as to the frequency and timing of intercourse and the timing of medications and studies in the infertility evaluation. It is our practice to write the various steps of the workup in the margins of a temperature chart. On the first consultation, the patient receives a written outline as to the steps that will be involved in their infertility workup. This reassures the couple that a plan has been established and will be carried out within a reasonable period of time.

SERUM PROGESTERONE.

The use of serum progesterone levels obtained at midluteal phase evaluates the occurrence and adequacy of ovulation and corpus luteum function. Most clinicians agree that a level of 10 ng/mL or greater is indicative of adequate ovulation (luteinization). Other investigators have suggested that three samples obtained in the luteal phase totaling 15 ng/mL constitutes normal ovulation. However, it should be remembered that progesterone is secreted in a pulsatile manner and a single low level may not indicate a defect of luteal function. Therefore, one might suggest that if progesterone is to be used as an index for ovulation it should be used in multiple cycles or that multiple levels should be drawn every other day during the luteal phase and averaged to yield a single result.

ENDOMETRIAL BIOPSY.

The endometrial biopsy may also be used to confirm ovulation and diagnose a luteal phase defect. It is usually performed late in the cycle, 1 to 2 days before expecting menstruation. The couple should refrain from intercourse or use barrier contraception during the cycle in which the endometrial biopsy is obtained. The sample of endometrium is obtained with a curette from the anterior or lateral wall of the uterine fundus. The dating of the endometrium is best correlated with the timing of ovulation as detected by sonogram or LH testing, rather than by backdating from the subsequent menstrual cycle. A delay in maturation of a single endometrial biopsy is a common finding and therefore must be repeated in another cycle before it may be interpreted as indicative of the presence of a luteal phase defect. Further, as stated previously, the use of sonography or urinary LH monitoring may enhance the predictive value of both midluteal progesterone measurement and endometrial biopsy.

PREOVULATORY SONOGRAPHY.

Preovulatory transvaginal sector sonography is a highly useful tool for evaluating adequate follicle development, endometrial assessment and oocyte release. A triple-line endometrial pattern seen on sonography before ovulation is predictive of subsequent pregnancy. Sonography is best used in combination with home LH urinary testing kits. It has been proposed that a considerable amount of previously unexplained infertility may be due to dysfolliculogenesis (the development of multiple small follicles that bring about premature or inadequate luteinization). Regardless of the method chosen to assess adequate ovulation, we suggest that luteal abnormalities be detected by various methods in multiple cycles before instituting therapy.

CLOMIPHENE CHALLENGE TEST TO ASSESS OVARIAN RESERVE.

It has long been documented that the development of diminished ovarian reserve reflects the process of follicular depletion and a decline in oocyte quality. This is a natural physiologic occurrence for women in their mid- to late 30s, even when they have ovulatory cycles. This process is associated with a rise in a woman’s FSH levels, especially in the follicular phase. Currently basal FSH is the best marker to assess ovarian reserve and predict response to supra-ovulation. The clomiphene challenge tests the ovarian reserve in women 35 years and older by measuring FSH levels on cycle day number 3 and then on day 10 after the administration of 100 mg of clomiphene citrate on cycle day 5 to 9. An abnormal test is when the day 10 sample is elevated. The mechanism is unknown, but is based on the fact that women with normal ovarian function and reserve should be able to overcome the impact of clomiphene by day 10. Adding clomiphene allows one to unmask patients who may not be detectable by basal FSH screening alone. This test is twice as sensitive as a single value basal FSH test. Its predictive value has been estimated at 85% for cycle cancellation secondary to poor ovarian reserve and 100% for failing to conceive. It is currently recommended that all women older that 34, and younger women with unexplained infertility should be screened in this manner. Women who have diminished ovarian reserve should be counseled regarding their options of oocyte donation or adoption.8

OTHER LABORATORY TESTS.

Serum TSH and prolactin levels are obtained in most women with infertility, and in all women with amenorrhea and or galactorrhea, Serum androgens are only obtained in hirsute women and gonadotropins are obtained in women over age 35 and in women with amenorrhea.

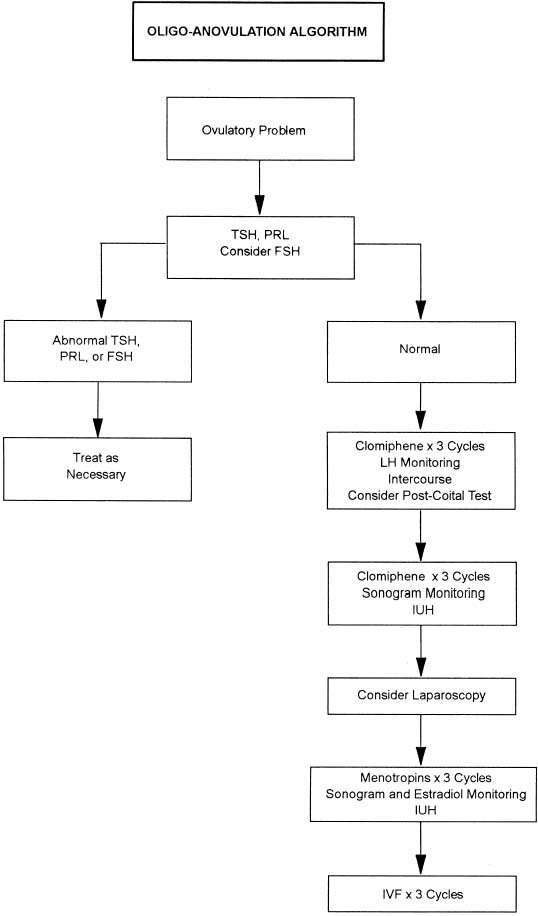

Basic Management

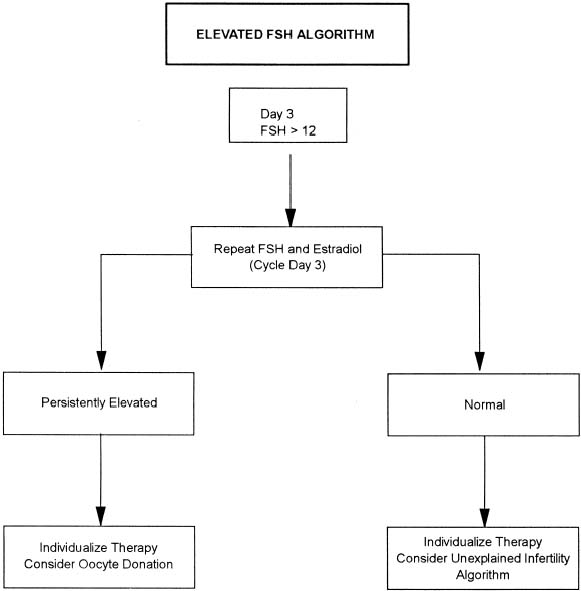

In women with ovulatory dysfunction with normal TSH, prolactin, and FSH (if indicated) levels, ovulation induction can be initiated with clomiphene citrate in appropriate doses to effect ovulation. Figure 4 outlines a treatment algorithm for infertile couples with oligo-anovulation. In patients who have not conceived after six ovulatory cycles, a diagnostic laparoscopy may be considered to evaluate for the presence of asymptomatic endometriosis or pelvic adhesions disease. Three cycles of menotropin therapy should then be initiated with estradiol and sonographic monitoring followed by intrauterine insemination with washed husband’s sperm (IUH). If pregnancy has still not been achieved, up to three cycles of in vitro fertilization (IVF) should be offered to the infertile couple. Patients with a day 3 FSH higher than 2 mIU/mL should have a repeat FSH and estradiol. With persistent elevation, oocyte donation should be considered (Fig. 5).10

In women with known polycystic ovarian syndrome characterized by hyperandrogenism and oligo-ovulation, fertility is a constant challenge. Two common endocrine features of this disease are increased circulating LH and hyperinsulinemia. For these women, if infertility is a problem, then recent evidence indicates that weight loss and treatment with insulin agents may be successful in inducing ovulation. Women who have a body mass index (BMI) higher than 27 should be encouraged to lose weight. This reduces the amount of circulating androgens and promotes ovulation induction. Furthermore, insulin sensitizers such as metformin have been shown to increase the number of ovulatory cycles in these women, especially in conjunction with clomiphene.11

BASIC LABORATORY TESTING: MALE

Semen Analysis

A semen specimen should be examined in all couples presenting with infertility. The specimen is obtained by masturbation into a sterile collection cup. Forty-eight to 72 hours of abstinence is recommended prior to analysis. The sample should be delivered to the laboratory within 1 hour of collection. The test should be insisted on despite a history of past paternity, because paternity may in fact be in doubt in a troubled relationship. Frequently, one encounters the infertile couple that has had a normal postcoital test in the past and this has been interpreted as adequate evaluation of the male. However, the postcoital test does not substitute for a formal semen analysis. Often, reluctance to obtain a semen analysis may be because of embarrassment or hesitation about masturbation. This can be overcome by the use of silicon condoms, which allow the man to produce a semen sample by intercourse. It should be noted, however, that most condoms are made with latex and should not be used for collection purposes because latex may be toxic to sperm. Also, most of these condoms are also coated with nonoxynol-9, which is a detergent that will disrupt cell membranes and is therefore a potent spermicide.

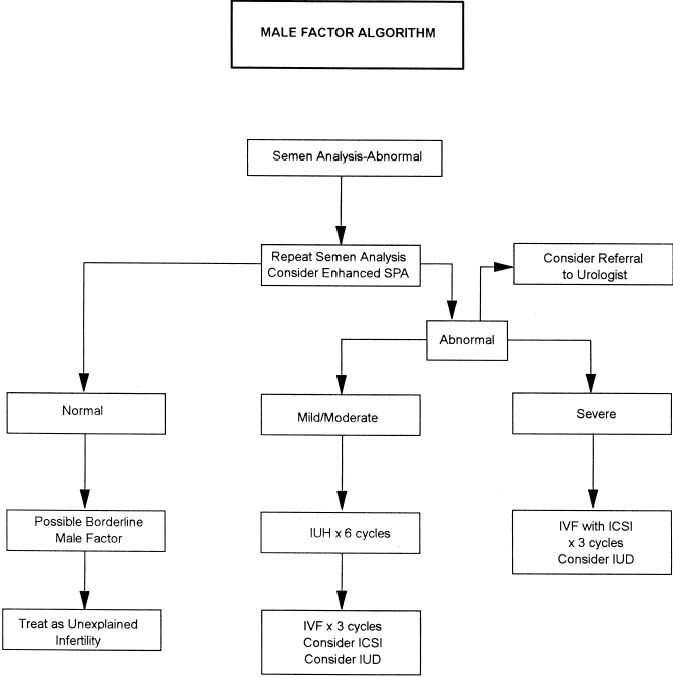

The semen analysis should have a volume of 2 to 5 mL, 20 to 200 million sperm per milliliter with 50% directional motility, 0% to 40% abnormal forms, liquefaction at room temperature in 1 to 20 minutes, and a pH of 7.0 with a range of 7.5 to 8.0. There is great variation from sample to sample in terms of volume, number, and motility. In addition, there may be seasonal variation in these values. Therefore, it is recommended that if an abnormality is found, a repeat analysis should be carried out 2 to 3 months later to determine the presence of a male factor. It is inappropriate to designate a male as infertile based on a single semen analysis. A treatment algorithm for male factor infertility is outlined in Figure 6.

The diagnosis of male factor infertility often leads to poor treatment outcome. However, with the emergence of ART, infertile couples with this problem have a better chance of pregnancy. Although techniques of IVF together with micromanipulation of gametes, such as intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), are advancing at rapid speed, intrauterine insemination (IUI) with the husband’s sperm still remains one of the treatment options available for couples diagnosed with male factor infertility. Although clinicians may offer IUI to patients as one of several possible options for the treatment of male factor infertility, patients often choose this as the first line of treatment.12

The use of IUI for the primary treatment of male factor infertility associated with severe oligospermia or oligoasthenospermia remains controversial because of extremely low pregnancy rates. For couples with severe oligospermia or those with sperm-directed antibodies, IVF may be a better choice. Couples with mild to moderate oligospermia, however, may be treated with IUI in conjunction with menotropins for controlled ovarian hyperstimulation prior to IVF. In men with repeat abnormal semen analysis, an enhanced SPA as well as referral to a urologist specializing in male infertility may be considered. Y chromosome analysis may be indicated in males with severe oligospermia. Persistent fertility can be treated with IVF with consideration of ICSI or the use of donor sperm.

TUBAL-UTERINE EVALUATION

Hysterosalpingogram

The HSG is still considered an important tool in infertility evaluation. The HSG provides information regarding the shape of the uterine cavity and patency of the fallopian tubes. It should be performed in the early follicular phase of the cycle, as soon as menstrual bleeding has ceased. This eliminates the risk of reflux of blood or performing the procedure during early conception. It is our practice to reduce the small chance of infection (1% to 3%) after this procedure by (1) avoiding performing the procedure in a woman with significant pelvic tenderness or adnexal mass suspected to be a tubo-ovarian complex, (2) chlamydia and/or gonococcal screening, (3) prophylactic antibiotics (usually doxycycline 100 mg twice daily beginning the day before the procedure and continuing until the day after, and (4) Betadine application to the cervix before this procedure. There has been some evidence that an HSG itself is therapeutic, and pregnancies have been reported after the procedure.13

For best results, it is recommended that not only the radiologist but also the physician be present during the HSG. In this way, the actual procedure can be adapted to specific needs as determined by the appearance on the monitor. The dye may be oil- or water-based; there are limited data to resolve which dye is preferred although there are some indications that the pregnancy rates are somewhat higher when an oil-based medium is used. In rare instances, HSG can result in allergic reactions or infections. Women who are allergic to iodine or are suspected of having occult infections should not undergo this procedure.

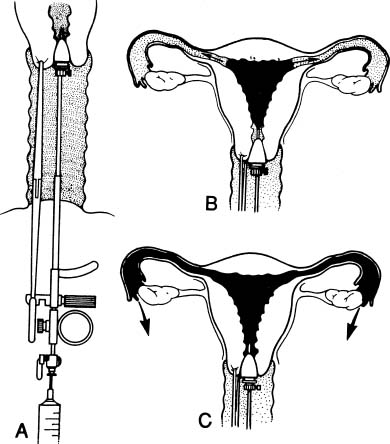

After an initial film, 3 to 5 mL of dye should be injected slowly to allow adequate visualization of the uterine cavity. A second film is then taken. Cervical traction is often necessary to completely evaluate the uterine cavity. A small acorn tip is preferred over balloon-type catheters because the latter obstructs the visualization of the cavity (Fig. 7). After this, another 5 mL is injected to evaluate tubal patency, followed by a third film. A follow-up film is taken to evaluate peritubal adhesions and usually is performed in 10 minutes (using water-soluble media) or 24 hours (using oil-based media).

El-Yahia14 recently described the results of laparoscopic investigation in 130 women after a normal HSG. Diagnostic laparoscopy was performed after an evaluation including normal semen analysis, pelvic examination, historical screening for pelvic inflammatory disease, prolactin and thyroxine assays, postcoital test, and confirmation of ovulation. All of the women reported at least 1 year of unprotected intercourse without conception. In this retrospective review, only 42.3% of the women were noted to have normal pelvic anatomy at laparoscopy. Pelvic adhesive disease was observed in 20% (27 patients). The remainder of abnormalities included pelvic endometriosis, pelvic inflammatory disease, and uterine leiomyoma. The impact of each of these gynecologic disorders, however, is not known. Cundiff et al.15 suggests that in infertile couples who have a normal HSG: (1) laparoscopy should not be performed until 3 months after a normal HSG because of the potential therapeutic effect of HSG, (2) laparoscopy should be performed after a normal HSG if pregnancy has not occurred by 6 months to 1 year because of the high incidence of pelvic pathology, and (3) HSG using water-soluble contrast media has a therapeutic effect comparable to that described for oil-soluble contrast media.

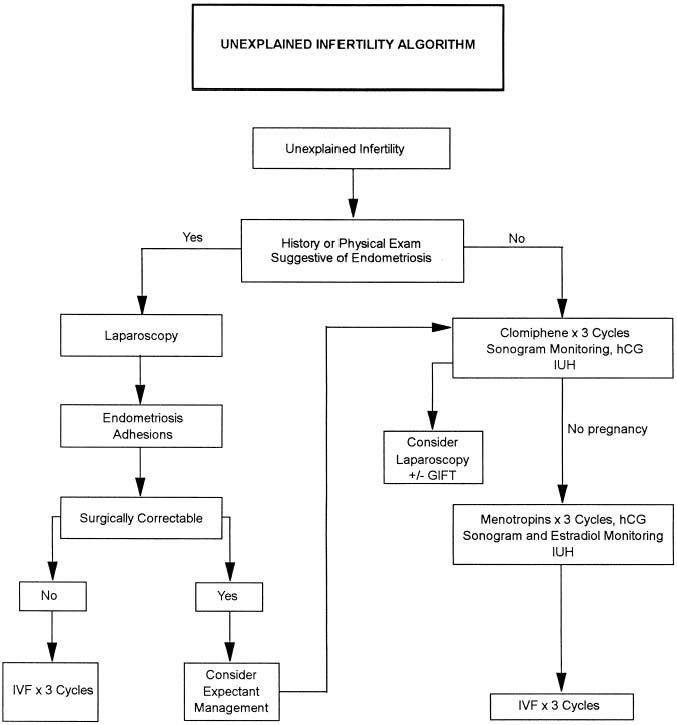

Mild distal tubal disease may be amenable to laparoscopic tuboplasty, while moderate to severe tubal occlusion is most effectively managed with IVF. IVF success increases when hydrosalpinges are removed surgically. When a proximal tube occlusion is evident on HSG, a laparoscopy and hysteroscopy with tubal cannulation should be performed. Uterine filling defects are evaluated with office hysteroscopy and treated appropriately. Patients with a normal HSG and laparoscopy evaluation are treated according to the unexplained infertility algorithm (Fig. 8).

Timing of Testing

In the first month of evaluation, the use of condoms or barrier contraceptives is suggested. On day 1 the woman begins the basal body temperature chart. An HSG is scheduled for days 7 to 11 of the cycle to avoid menstruation and the possibility of radiation exposure to a potential embryo. Home urine LH testing is begun on day 10 through 18. A serum progesterone level is obtained on day 21 or more accurately 7 days after the LH surge. An endometrial biopsy is taken on day 25 to 28, again most accurately dated to LH surge. During this time a semen analysis is also obtained.

In the second month, a follow-up visit is scheduled. This may be done day 12 to 14 or after the LH surge at which time a postcoital test is performed if indicated. At this time test results, HSG films, and other data is reviewed with the couple (Table 3).

TABLE 3. Timing and Coordination of Infertility Testing

Month 1 Following 1st Visit (Barrier Contraceptives Recommended) | |

Day 1 | Initiate BBT |

Days 7–11 | HSG |

Days 10–18 | LH urine testing |

Day 21 (or 1 week after LH surge) | Progesterone level |

Days 25–28 | Endometrial biopsy (dated to LH surge) |

Days 1–28 | Semen analysis |

Month 2 | |

Days 12–14 | PCT (or at LH surge) |

Review test results, confirm diagnosis, and plan treatment or schedule other tests in indicated | |

BBT, basal body temperature; HSG, hysterosal pingo gram; LH, luteinizing hormone; PCT, postroital test.

(From Bradshaw KD, Carr BR: Diagnostic evaluation of the infertile couple. In Carr BR, Blackwell RE[eds]: Textbook of Reproductive Medicine, Stamford, Appleton & Lange, 1993)

After these tests further evaluation may be indicated. If all tests are normal, or if the HSG suggests tubal pathology a laparoscopy or hysteroscopy may be indicated.

FURTHER DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

Laparoscopy/Hysteroscopy

Laparoscopy is not always considered a routine part of the infertility evaluation. A laparoscopy is performed when all other tests have been normal (Fig. 8), or when there is reason to suspect intra-abdominal pathology (such as endometriosis, pelvic adhesions, ovarian pathology, or uterine leiomyoma). Laparoscopy is scheduled in the early to midfollicular phase of the cycle in order to avoid disrupting a pregnancy or a well-vascularized corpus luteum. If hysteroscopic surgery is planned because of a suggestive abnormality of the HSG (and adhesions, septums, or leiomyomas), it may be useful to pretreat the patient with gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues or Danazol to reduce the height of the endometrium, thereby increasing visualization.

The prognostic value of laparoscopic diagnoses and treatments remains an area of controversy. The real prevalence of undetected, although clinically important pelvic disease and the benefit to long-term fecundity of laparoscopic treatment are incompletely understood and probably varies as a result of many factors. Some suggest that surgery is either indicated or suggested: (1) when infertility surgery is simple and likely to increase the chance of conception (i.e., removal of a septum, lysis of adhesions, or hysteroscopic tubal cannalation), (2) when there is chronic pelvic pain, ovarian, tubal, or uterine pathology that may interfere with successful conception or IVF, and (3) when there are complications of fertility treatments (i.e., ectopics).

Although previously lower, recent success rates for the removal of peritubular adhesions has been shown to be up to 70%.16

Women with chronic pelvic pain and infertility often will warrant laparoscopic evaluation. Some form of pathology will be detected in more than 60% of laparoscopy done for chronic pelvic pain.17 Endometriosis is the most common pathology diagnosed in these women with chronic pelvic pain. However, the majority of these cases are mild, a condition perhaps simply associated with, rather than contributing to infertility. The much more severe cases are less frequent, but generally more accepted as directly causative of infertility. Surgical treatment of endometriosis often aids in the patient’s pain and may decrease complications or increase the success of an IVF cycle.

Suspicious adnexal masses should also be evaluated surgically before fertility treatments. It is especially important to rule out malignancy in light of the increasing age of women attempting conception. Further, a greater than 3.5 fold increase in deliveries after IVF has been reported in women who had salpingectomy for bilateral hydrosalpinges. Although the mechanism of interference of hydro-salpinx is unknown, the data is clear.16

Submucosal or intramural fibroids that distort the uterine cavity increase infertility and should be removed to aid in conception as well. The most beneficial mode of removal today is with hysteroscopy. Laparoscopy and laparotomy for myomectomies have many complications including adhesion formation, infection, and risk of uterine rupture or cesarean section. Removal of the intramural fibroids with hysteroscopy is a minor procedure involving minimal morbidity.

Most infertility procedures can be performed via the laparoscope and/or hysteroscope using video monitoring. Thus, the surgeon should be able to perform these procedures if indicated. An inexperienced gynecologist or one who only rarely performs laparoscopic (operative laparoscopy, pelviscopic surgery) or hysteroscopic surgery should refer the patient to a reproductive endocrinologist or reproductive surgeon. Hysteroscopy usually requires dilation of the cervix and use of distending medium such as Hyscon, sorbitol, or glycine. After this procedure a cannula or catheter should be inserted into the cervix so that methylene blue or indigo carmine dye can be injected during laparoscopy to evaluate tubal patency.

The laparoscopic procedure should be performed under general anesthesia in a steep Trendelenburg position. The laparoscope is usually inserted after carbon dioxide insufflation with a verris needle through the umbilicus, although recent studies suggest that similar results and safety can be obtained with direct trocar insertion, followed by carbon dioxide instillation.18 After the peritoneal cavity is visualized, one or two secondary punctures are required to adequately visualize pelvic structures. A thorough evaluation in a planned, clockwise, organized manner is required to rule out pelvic pathology. Proper staging by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine for pelvic adhesions, tubal disease, and endometriosis should be performed. Photographing or videotaping is often helpful to document disease.

In women who have a normal laparoscopy or who have undergone surgical correction of endometriosis or adhesions, expectant management or a more aggressive treatment for unexplained infertility may be pursued. Utilizing this algorithm, patients undergo three cycles of clomiphene citrate stimulation with sonogram monitoring, hCG, and IUI. If no pregnancy results, laparoscopy with GIFT or three cycles of menotropin therapy and IUI should be offered prior to proceeding to IVF.

ADDITIONAL OPTIONAL TESTS

Postcoital Testing

A postcoital test has been advocated to evaluate the presence of cervical factors. Unfortunately, most poor postcoital tests are the result of inadequate timing. Most often the test is performed on day 12 of the cycle, but if ovulation occurs earlier or later the test will often result in immobile sperm.19 It has been our observation that many so-called cervical factors have at their origin poor timing or inadequate follicle development with poor estrogen production.

There is considerable lack of standardization in postcoital testing. The test should be done 24 to 36 hours prior to ovulation (determined by urinary LH testing) and from 0 to 4 hours after intercourse. At that time one should find an open cervix and clear cervical mucus with spinnbarkeit 8 to 10 cm and 5 to 15 directionally motile sperm per high-power field.

Despite the manner in which the postcoital test is carried out, some investigators have suggested that it provides little information regarding potential fertility. Support for this contention comes from the finding of sperm in the peritoneal fluid at laparoscopy in patients having poor postcoital tests and the finding that 27% of fertile couples show either no sperm or fewer than 1 sperm per high-power field in their postcoital test. Nevertheless, at a minimum, information is gained about the adequacy of coital technique if a normal postcoital test is obtained.

Male Immunologic Causes of Infertility

The testis is an immunologically protected site because of the blood-testis barrier. Although there are other causes of male immune infertility such as autoimmune orchitis, the most common cause of male immunologic infertility is anti-sperm antibodies (ASA).20 The incidence of anti-sperm antibodies is less than 2% in serum, sperm, and cervical mucus in fertile men and women. However, the levels range from 5% to 25% in serum, sperm, and cervical mucus of infertile couples.21

The actual infertility mechanism of ASA is unknown. Multiple theories have been proposed involving all steps of sperm-egg interaction. Most intriguing is that the simple presence of ASA alone may or may not necessarily cause deleterious affects. The particular sperm antigen bound by an ASA may result in no effect or a harmful effect.

It is difficult to determine which clinical scenarios warrant testing for ASA. Some considerations are helpful in choosing which couples should be tested for ASA. Abnormalities of the semen analysis may predict the presence of ASA. Clinical conditions in which the blood-testis or excurrent ductal system is breached, such as a history of testicular biopsy, vasectomy reversal, or obstructive lesion of the male ductal system, should be tested. The absence of motile sperm in midcycle cervical mucus after intercourse has been correlated with sperm-associated ASA in approximately 50% of men. Clumping found on the standard semen analysis may also be consistent with antibodies. Sperm agglutination frequently is a result of genital tract infection caused by prostatitis, urethritis, or epididymitis. These disorders should be treated with antibiotics before testing for sperm antibodies.

As many as 17% of women in couples with unexplained infertility are found to have serum ASA. Women with a history of frequent receptive anal or oral intercourse should be considered for ASA testing, although no conclusive evidence linking these two is present. Specific tests for ASA in cervical mucus, serum, and seminal plasma are available; at present the immunobead assay and the mixed agglutination assay are recommended. The theory behind these tests is that sperm exposure to the female immune system may result from genital tract obstruction with a resulting immune response to sperm in the cervical mucosa.20

The significance of these tests in regard to infertility workup is not always clear because some couples have been known to conceive in the presence of high levels of ASA.22 However, physicians believe that decreased or impaired movement of sperm through genital tract secretions and failure of fertilization may be due to sperm antibodies. Patients with high levels of antibodies and prolonged infertility should be offered IVF with possible ICSI to circumvent the mechanisms of ASA.

Female Immunologic Causes of Infertilty

Immune assault on the components of the ovary can lead to diminished ovarian function and even premature ovarian failure. Autoimmunity has been shown to cause up to 20% of premature ovarian failures. Addison’s disease is the most common cause of autoimmune infertility. Further evaluation of the female immune factor is difficult secondary to a lack of standardized ovarian antibody assays.20

PSYCHOLOGICAL EVALUATION

Every aspect of the infertility evaluation evokes some emotional and psychological stress for the couples involved. Many times in a large, busy medical practice, it may be difficult for physicians to spend the time necessary to allow frustrated couples to verbalize their feelings and give feedback on management and outcomes. Investigators have found a higher incidence of emotional disturbance in infertile women than among matched controls. Infertile couples have described themselves as being “damaged,” “defective,” “hollow,” and “empty.”23

The physical and mental consequences of the infertility workup, subsequent treatment, and lack of success may either cause or greatly exacerbate a psychological problem. Physicians who treat infertile couples should be aware of the enormous stress that infertility places on both partners, and to understand the psychological interventions that are effective in alleviating some of the stress. Probably all couples experiencing infertility could greatly benefit from counseling and in our practice all new patients are offered follow-up with a professional psychologist who is trained with associated infertility problems. There are three times in the evaluation and therapy that intervention is encouraged: (1) at the beginning of the infertility evaluation, (2) when psychiatric indications are obvious, and (3) at the termination of unsuccessful treatment or with a pregnancy loss. Couples participating in artificial insemination donor or donor oocyte are all strongly encouraged to seek counseling.

Anxiety often occurs during the infertility evaluation. However, depression seems to be the most common reaction to failed fertility treatment. Because many couples believe this is their last hope for a biologic child, their expectations are great. In fact, failed outcome may translate into a loss of a loved one, which is commonly associated with depression. The percentage of patients who develop an episode of depression after failed IVF ranges from approximately 25% to 40%. There is also a suggestion that the severity of the response varies over time. One group24 found that women with 2 to 3 years of infertility had higher depression scores than women who had either longer or shorter durations of infertility.

Therapy for infertility rarely offers a clear end point for cessation after repeated failures. Paulson and Sauer25 suggest that all couples establish an ongoing relationship with a qualified counselor, are given the option of stopping treatment from the start, and are encouraged to seek second opinions throughout treatment. Some couples require time off from treatment to regroup, decrease their level of stress, and to re-evaluate their decision to continue treatment. Arbitrary time limits, based on known success rates and life-tablele analysis should be set at the beginning of treatment regimens so that if conception does not occur prognosis and options can be reassessed. For some couples this may be the time to stop or interrupt treatment for period of time or may be the time to begin adoption proceedings.

Although the primary objective is to achieve a successful term pregnancy, only 50% to 60% of infertile couples will be successful based on this parameter alone. In addition to those couples who simply fail to conceive, other failures will be related to spontaneous abortions, ectopic pregnancies, and other obstetric complications that have no tendency to spare infertile patients.25 It is therefore imperative that we assist couples in dealing with all realistic possibilities relative to outcome. The clinician should be motivated by a commitment to continuous analysis that demonstrates that patients have had comprehensive evaluations, an organized approach to therapy, and when unsuccessful, receive help in achieving the personal adjustment to a life crisis known as resolution.

REFERENCES

Tietze C, Guttmacher AF, Rubin S: Time required for conception in 1727 planned pregnancies. Fertil Steril 1:338, 1950 |

|

Hendershot GE, Mosher WD, Pratt WF: Infertility and age: An unresolved issue. Fam Plann Perspect 14:287, 1982 |

|

Bradshaw KD, Carr BR: Modern diagnostic evaluation and treatment algorithms for the infertile couple. In Carr BR, Blackwell RE (eds): Textbook of Reproductive Medicine. 2nd edition. pp 533, 547 Norwalk, CT, Appleton-Lange, 1998 |

|

Green JA, Robins JC, Scheier M, et al: Racial and economic demographics of couples seeking infertility treatment. Am J Obstet Gynecol 184:6, 2001 |

|

Silva PD, Cool JL, Olson KL: Impact of lifestyle choices on female infertilty. J Reprod Med 44:3, 1999 |

|

Shiverick KT, Salafia C: Cigarette smoking and pregnancy I: Ovarian, uterine, and placental effects. Placenta 20:1999 |

|

Hembree WC, Zeidenberg P, Nahas GG: Marijuana’s effect on human gonadal function. In Nahas GG (ed): Marijuana, Chemistry, Biochemistry and Cellular Effects. p 521, New York, Springer-Verlag, 1976 |

|

Sharara FI, Scott RT, Seifer DB: The detection of diminished ovarian reserve in infertile women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 179:3, 1998 |

|

Chantilis SJ, Carr BR: Evaluation and treatment of the infertile couple. In Quilligan EJ, Zuspan F (eds): Current Therapy in Obstetrics & Gynecology. p 83, Philadelphia, W.B. Saunders, 2000 |

|

Scott RT, Jr, Hofmann GE: Prognostic assessment of ovarian reserve. Fertil Steril 63:1, 1995 |

|

Barbieri RL: Induction of ovulation in infertile women with hyperandrogenism and insulin resistance. Am J Obstet Gynecol 183:6, 2000 |

|

Dodson WC, Haney AF: Controlled ovarian hyperstimulation and intrauterine insemination for treatment of infertility. Fertil Steril 55:457, 1991 |

|

Alper MM, Garner PR, Spence JEH, et al: Pregnancy rates after hysterosalpingography with oil- and water-soluble contrast media. Obstet Gynecol 68:6, 1986 |

|

El-Yahia AW: Laparoscopic evaluation of apparently normal infertile women. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol 34:440, 1994 |

|

Cundiff G, Carr BR, Marshburn PB: Infertile couples with a normal hysterosalpingogram: Reproductive outcome and its relationship to clinical and laparoscopic findings. J Reprod Med 40:19, 1995 |

|

Keye WR: Infertility: Is there a role for the surgeon? Clin Obstet Gynecol 43:4, 2000 |

|

Porpora MG, Gomel V: The role of laparoscopy in the management of pelvic pain in women of reproductive age. Fertil Steril 68, 1997 |

|

Byron JW, Fujiyoshi CA, Miyazawa K: Evaluation of the direct trocar insertion technique at laparoscopy. Obstet Gynecol 74:423, 1989 |

|

Griffith CS, Grimes DA: The validity of the postcoital test. Am J Obstet Gynecol 162:615, 1990 |

|

Hatasaka H: Immunologic factors in infertility. Clin Obstet Gynecol 43:4, 2000 |

|

Marshburn PB, Kutteh WH: The role of anti-sperm antibodies in infertility. Fertil Steril 61:799, 1994 |

|

Haas GG: Anti-sperm antibodies in infertile men. JAMA 275:11, 1996 |

|

Seibel M, Taymor M: Emotional aspects of infertility. Fertil Steril 37:137, 1982 |

|

Boivin J, Takefman JE, Tulandi T, et al: Reactions to infertility based on extent of treatment failure. Fertil Steril 63:801, 1995 |

|

Paulson RJ, Sauer MV: Counseling the infertile couple: When enough is enough. Obstet Gynecol 78:462, 1991 |