Septic Abortion: Prevention and Management

Authors

INTRODUCTION

Septic abortion, an infected abortion complicated by fever, endometritis, and parametritis,1 remains one of the most serious threats to women’s health worldwide. Although morbidity and mortality from septic abortion are infrequent in countries in which induced abortion is legal, suffering and death from this process are widespread in many developing countries in which abortion is either illegal or inaccessible. Septic abortion is a paradigm of preventive medicine, relating to all levels of prevention – primary, secondary, and tertiary.2 In the past, obstetricians/gynecologists were often the experts in management of sepsis. However, those who have trained where abortion is legal may have little experience with septic abortion, so management is reviewed in some detail.

SCOPE OF THE PROBLEM

United States

A 1973 report from a prestigious medical journal described an adolescent admitted to a major Boston teaching hospital with what proved to be incomplete septic abortion. Uterine evacuation was not performed until several days after admission because this diagnosis was not initially entertained. The patient died despite massive antibiotic therapy and intensive medical management.3 Tragedies of this sort are now rare in the US.

The most important public health effect of the legalization of abortion4 was the near elimination of deaths from illegal abortion in the United States. Illegal abortion deaths are disproportionately due to infection.4, 5 In a 1994 US review, 62% of illegal abortion deaths and 51% of spontaneous abortion deaths were from infection, whereas only 21% of legal abortion deaths were from infection.6 More recent breakdowns by cause of death are not available due to the rarity of legal abortion deaths. Risk of death from postabortion sepsis is greatest for younger women and unmarried women, and it is more likely with procedures that do not directly evacuate the uterine content.7 With more advanced gestations, the risk of perforation and retained tissue increases.7 Delay in treatment allows progress to bacteremia, pelvic abscess, septic pelvic thrombophlebitis, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, septic shock, renal failure, and death.8

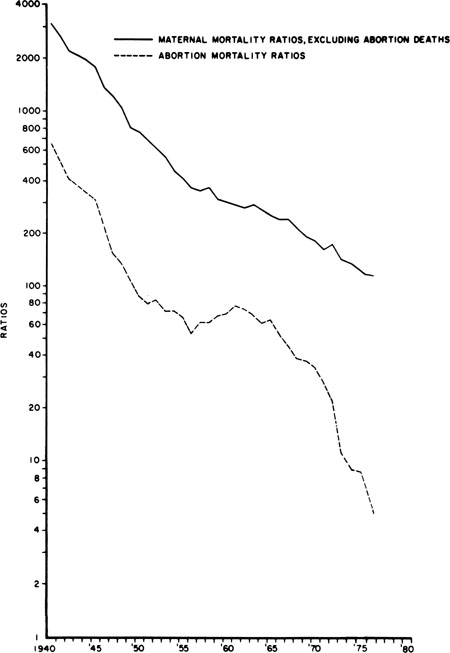

US maternal deaths from all causes have declined rapidly since 1940.9 Non-abortion maternal mortality has declined steadily. Abortion mortality exhibited three phases: an initial decline until 1950, a plateau from 1951 to 1965, and then a very rapid decline from 1965 to 1976 (more rapid than that of maternal mortality from other causes) as legal abortion became increasingly available (Fig. 1). For 2009, the last year for which complete data are available, eight abortion deaths were reported by the US Centers for Disease Control.10 The case fatality rate for 2003–2009 was 0.67 per 100,000 induced abortions.10 By comparison, in the 1940s, prior to the legalization of abortion over 1000 women per year were known to have died from abortion in the United States.5 The case fatality rate for 1973–1977 (immediately following legalization of abortion in the US) was 2.09.10 The American Medical Association’s Council on Scientific Affairs has attributed the marked decline in abortion deaths in that century to the introduction of antibiotics to treat sepsis, the widespread use of effective contraception beginning in the 1960s, which reduced the numbers of unwanted pregnancies, and more recently, the shift from illegal to legal abortion.11

Serious complications have become rare as well. A large series from Planned Parenthood of New York City describes 170,000 abortions performed in outpatient settings by a small group of expert practitioners. No deaths occurred, and only 121 hospitalizations for complications occurred, 0.71 per 1000 abortions.12 Approximately 3.2 million unintended pregnancies occur each year in the US13 and with the continuing attack on legal abortion services14, 15 and current barriers to access,16 the demand for abortion is leading to a resurgence in illegal and self-induced abortion. Recent case reports from the US include a 24-year-old woman who presented after attempting to self induce abortion of 24 weeks twins with a steel coat hanger inserted through her own cervix. She survived severe chorioamnionitis and systemic sepsis after total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral oophorectomy.17, 18, 19

Fig. 1. Maternal mortality ratios per 100,000 live births, excluding abortion deaths and abortion mortality ratios, in the United States from 1940 to 1976. Maternal non-abortion mortality ratio equals maternal deaths minus abortion deaths per 1 million live births. Abortion mortality ratio equals abortion deaths per 1 million live births. Data are from United States Vital Statistics, National Center for Health Statistics, 1940–1976. (Cates W Jr, Rochat RW, Grimes DA, et al: Legalized abortion: Effect on national trends of maternal and abortion related mortality (1940 through 1976). Am J Obstet Gynecol 132:211, 1978.)

Western Europe and the Former Soviet Union

The experience in Western Europe has been very similar to that in the United States, with legal abortion becoming widely available and very low rates of abortion mortality currently reported. Overall, maternal mortality from legal abortion in Europe is less than 1 per 100,000 procedures.20 Death rates are somewhat higher in the former Soviet Union, where the particular problem of induced abortion as the primary method of family planning has emerged. Recently the Russian parliament has tightened restrictions on abortion which may lead to an increase in illegal abortion.21

The developing world

Unsafe abortion remains a major cause of maternal death in developing countries. WHO defines abortions as unsafe when they are performed by individuals lacking the necessary skills, or in an environment that does not conform to minimal medical standards, or both. In 2008 an estimated 49% of all 44 million abortions worldwide were considered unsafe and 98% of unsafe abortions occurred in developing countries. In developing countries 56% of abortions were unsafe, compared to 6% in developed countries.20 WHO estimates that 47,000 deaths from unsafe abortion occur in the world every year. Worldwide, an estimated five million women are hospitalized each year for treatment of abortion-related complications, such as hemorrhage and sepsis.22 About 1 in 8 maternal deaths globally are attributed to unsafe abortion.23 Most of these maternal deaths occur in underdeveloped countries with the highest burden in Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean.22 The proportion of maternal deaths that result from unsafe abortion is probably considerably larger than available estimates. Where abortion is illegal, women and health care professionals are reluctant to report that abortion was induced.24 Private personal dialogue with women by trained, empathetic caseworkers reveals a higher proportion of induced abortions.25

The preventable morbidity and mortality from septic abortion are staggering and well documented.26 A 1992 report of Guinea, in West Africa, reported an investigation of all maternal deaths in the capital from July 1, 1989 to June 30, 1990. The most common causes were hypertensive diseases (20%), postpartum bleeding (19%), and abortion (17%). Eighty per cent of the abortion deaths were known to be from induced abortion. Sepsis was the most common cause of death.27 A study from five hospitals in Kampala, Uganda, in East Africa, for the period 1980–1986 found 20% of maternal deaths to be abortion-related.28 A Nigerian study reported that 35% of hospital maternal mortality was from abortion, with sepsis the most common cause of death.29 A 7-year review of abortion at the University College Hospital in Ibadan, Nigeria, reported that abortion complications represented 77% of all emergency gynecologic admissions.30 A population-based survey in rural Bangladesh identified 387 maternal deaths from 1976 to 1985 (555 per 100,000 live births). Principal causes of death were postpartum hemorrhage (20%), abortion (18%), and pregnancy induced hypertension/eclampsia (12%).31

In 1990, 36 hospitals and medical schools from four Latin American countries participated in a multinational study of all women attending for abortion during a 6-month period.32 During this time, 14,501 abortion admissions were recorded and 8871 were investigated. At the same time 113,714 births occurred in the participating hospitals. Fifteen per cent of the abortions were classified as septic on admission. Forty-three women of the 8871 required hysterectomy, and 36 women died, producing an abortion mortality rate of 406 per 100,000 women admitted for abortion. Although hemorrhage was the most common abortion complication, 75% of the deaths were in women admitted as “septic”. The problem may actually be escalating in some areas. A 10-year review from Rio de Janeiro found maternal mortality to have increased almost fourfold from 1978 to 1987 (128 per 100,000 to 462 per 100,000). Abortion-related deaths accounted for 47% of the total mortality.33 As shown in all of these studies, abortion deaths are primarily from sepsis.

More recent reports from many countries echo the same dismal findings. A report of a 10-year study from rural India, published in 2001, found that 41.9% of all maternal deaths were from septic abortion, and the total maternal mortality rate was extraordinary (785 per 100,000 live births), approximately 100-fold greater than maternal mortality in developed countries.34

A report from WHO showed a decline in maternal mortality worldwide from 546,000 deaths in 1990 to 358,000 in 2008, and a parallel decline in death from unsafe abortion from 69,000 to 47,000 over the same interval. However, the proportion of maternal deaths that are from unsafe abortion remains the same, 13%. The actual number of unsafe abortions worldwide increased from 19.7 million in 2003 to 21.6 million in 2008 because of the growth of the population of women of childbearing age.20, 35

PRIMARY PREVENTION OF SEPTIC ABORTION

Primary prevention avoids the occurrence of disease or injury.2 Primary prevention of septic abortion includes access to effective and acceptable contraception; access to safe, legal abortion in case of contraceptive failure; and appropriate medical management of abortion.

Avoiding unintended pregnancy

Pregnancy places women at risk for illness and death. This risk may be gladly assumed with a desired pregnancy. Unwanted pregnancy places a woman at additional risk if she seeks abortion and safe services are not available.36, 37 Reducing unwanted pregnancies is a goal to which both sides in the abortion controversy can agree, although the means to that end diverge.

A prerequisite to preventing unwanted pregnancy – in all nations – is social equality: the elevation of women’s status so that they can avoid coercive sexual relationships and use contraceptive methods that they regard as safe and free of side effects.36 In the United States, age-specific abortion ratios make it clear that women at greatest risk for unwanted pregnancy are adolescents and young adults.10 Marriage and intentional childbearing are delayed, but sexual activity is not. National surveys consistently show 11–12% of reproductive-age women to be sexually active with no use of contraception.38 Publicly funded contraceptive services do not reach all who need them. No increase in the funding for public family planning services has been seen in more than a decade, and the US 112th Congess attempted to remove all federal funding for family planning clinics. Sexuality education often fails to inform about contraception because of a misguided notion that such education about contraception encourages sexual experimentation. In fact, adolescents coming to family planning clinics are typically sexually active long before seeking services.39 Education about biology is not enough. Actual services must be provided that are readily accessible and inexpensive (Table 1).

Table 1. Components of safe surgical abortion services

Confirm diagnosis of pregnancy with urine pregnancy test

Provide nonjudgmental counseling

Evaluate patient for active illness that might complicate procedure or choice of anesthetic, and evaluate for allergies

Perform appropriate physical examination

Perform pelvic examination with attention to uterine size and position, other pelvic pathology

Obtain ultrasound examination if length of gestation is uncertain, there is a discrepancy between length of amenorrhea and uterine size, there is a pelvic mass, or gestational age is beyond early midtrimester

Perform minimal laboratory testing: blood type and Rh status

Provide prophylactic antibiotics (e.g., doxycycline 100 mg PO, two doses prior or immediately after the procedure)4

Encourage local anesthesia: paracervical block

Dilate cervix with tapered dilators (Pratt or similar) or use hygroscopic dilators (laminaria or synthetic alternatives Dilapan* or misoprostol 400 µg by the buccal or sublingual routes 3 hours prior)

Use vacuum cannula diameter appropriate for uterine size (diameter in mm one less than estimated gestational age in weeks)

Perform fresh examination of tissue to exclude incomplete or failed abortion, ectopic and molar pregnancy

Alternatively, provide medical abortion with mifepristone and misoprostol, or misoprostol alone if mifepristone is not available

Provide access to 24-hr follow-up services

Actively track high-risk patients

*Gynetech, Lebanon, New Jersey, USA

Data from Hern WM: Abortion Practice. Philadelphia, JB Lippincott, 1984; and Stubblefield PG: Pregnancy termination. In Gabbe SG, Niebyl JR, Simpson JL (eds): Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies, pp 1303–1332. 2nd ed. New York, Churchill Livingstone, 1991

Access to safe abortion services

The need for safe, legal abortion is nowhere more clearly shown than in the Romanian experience. When abortion was outlawed in the 1960s, the abortion-related maternal mortality rate rose 10-fold. An estimated 10,000 women died from this policy over the 23 years of its imposition.40 The death rate fell only when abortion was again legalized. The public health message of this bizarre natural experiment is clear: when abortion is legal and accessible, women’s health improves, and vice versa. No evidence supports the claim that restricting abortion reduces the number performed. Abortion rates and ratios are as high or higher in countries in which abortion is completely illegal than in countries in which it is legal and readily available.41

The need for safe legal abortion was again shown in the Nepal experience. Between 1996 and 2006 maternal mortality fell dramatically from 539 to 281 deaths per 100 000 live births. This dramatic decline correlated with the legalization of abortion in Nepal in 2002. Safe abortion services are available in all 75 districts and more than 400,000 women have benefited between 2002 and 2010.42 This impressive decline was attributed in part to the scale up of safe abortion services. In South Africa abortion related deaths fell by 91% between 1994 and 1998–2001 following legalization of abortion in 1997.43

Components of safe abortion services

The risk from abortion rises with gestational age, increasing in the second trimester.10 Therefore, safe services are needed early in pregnancy. Access is especially a problem for disadvantaged women, including the young, who in many jurisdictions must seek consent from their parents for abortion, but who may continue a pregnancy, a far more dangerous course, on their own.44 The technology for first trimester abortion is not complicated (Table 1). In the first trimester and early midtrimester, abortion is readily performed by vacuum curettage in an outpatient or office setting.45, 46 Prophylactic antibiotics reduce the risk of febrile morbidity after abortion.47

SECONDARY PREVENTION OF SEPTIC ABORTION

Secondary prevention requires early detection and treatment, with the goal of halting the disease process.2 Secondary prevention of septic abortion entails prompt diagnosis and effective treatment of endometritis to avoid more serious infections. The diagnosis of septic abortion must be suspected when any reproductive-age woman presents with vaginal bleeding, lower abdominal pain, and fever. A common theme in reported deaths from septic abortion is delay: young or unmarried women often conceal the abortion and delay seeking help until moribund. In this setting, a sensitive pregnancy test (capable of detecting 20–50 mIU/mL of beta-human chorionic gonadotropin [beta-hCG]) will usually be positive, because it takes 4–6 weeks for beta-hCG to become undetectable after complete uterine evacuation.

A rapid initial assessment is needed to determine the severity of the problem. If the patient has been symptomatic for several days, more generalized, serious illness may be present. When possible, the abortion provider should be contacted to determine details of the procedure – whether complications were suspected at the time, the length of gestation, and quantity of pregnancy tissue removed, results of any screening bacteriologic studies, and pathologic examination of aborted tissue. With more advanced gestations, there is greater risk of perforation and of retained tissue. Perforation markedly increases the risk of serious sepsis.7 Illegal abortion by insertion of rigid foreign objects increases risk of perforation.48 Intrauterine instillation of soaps poses a special hazard for uterine necrosis and renal failure.49

The abdominal and pelvic examinations merit special attention. The examiner should note abdominal tenderness, guarding, and rebound, and whether tenderness is limited to the lower abdomen (pelvic peritonitis) or is present over the entire abdomen (generalized peritonitis). Are vaginal or cervical lacerations present? Is there a foul odor? Are products of conception or pus visible in the cervical os? Is the uterus enlarged and tender? Is there an adnexal mass? If there is suspicion of perforation, radiographic studies of the abdomen may help identify free air or foreign bodies. Some women develop a mild illness, presenting with a triad of symptoms: low-grade fever, mild lower abdominal pain, and moderate vaginal bleeding. Patients presenting with these symptoms usually have either incomplete or failed abortion (continuing pregnancy) or hematometra (retained clotted and liquid blood).50 Ideal management is immediate re-evacuation in the ambulatory clinic or the emergency room. This can be readily accomplished safely and humanely by vacuum curettage with local anesthesia and intravenous sedation. In a large US series, 3.5 patients per 1000 had re-evacuation in the abortion clinic, which undoubtedly contributed to the authors’ remarkably low rate of hospitalization for septic abortion, 0.21 per 1000.51

The bacteriology of septic abortion is usually polymicrobial, derived from the normal flora of the vagina and endocervix, with the important addition of sexually transmitted pathogens.52 Gram-positive and gram-negative aerobes and facultative or obligate anaerobes, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and Chlamydia trachomatis are all possible pathogens.8, 46 In the United States, infection with Clostridium perfringens is largely associated with illegal abortions.8 Recently Clostridium sordellii has been the cause of death in a small number of women treated with mifepristone and vaginal misoprostol for early medical abortion.53 In developing countries, tetanus contributes to septic abortion death.26 Because of the variety of bacterial agents found in infected abortions, no one antibiotic agent is ideal. The recommended regimens of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for outpatient management of pelvic inflammatory disease are appropriate for patients with early postabortal infection limited to the uterine cavity in addition to uterine evacuation. One such regimen is ceftriaxone 250 mg by intramuscular injection (or other third generation cephalosporin such as cefoxitin, ceftizoxime, or cefotaxime) plus doxycycline 100 mg orally twice a day for 14 days, with or without metronidazole 500 mg orally twice a day for 14 days.54 Because of the spread of quinolone resistant gonococcus, quinolone regimens are no longer first choice for outpatient management of pelvic inflammatory disease in the US.54

TERTIARY PREVENTION OF SEPTIC ABORTION

Tertiary prevention minimizes the harm done by disease and avoids disability.2 Tertiary prevention of septic abortion seeks to avoid serious consequences of infection, including hysterectomy and death.

Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) is the manifestation of inflammatory response. SIRS is characterized by fever >38°C, tachycardia >90 bpm, tachypnea RR >20, white blood cell count >12,000 or <4000, or >10% immature forms. Septic shock includes SIRS plus a suspected or present infection. Severe sepsis includes SIRS plus evidence of organ dysfunction.evidence of organ dysfunction in the setting of bacteremia.55 Septic shock is suggested by tachycardia (>110), respiratory distress, oliguria, altered mental status, and hypotension despite adequate fluid resusitation.8, 50, 55

Patients with more established infection, as indicated by temperature elevation (arbitrarily defined as >38°C), pelvic peritonitis, or more severe disease, should be hospitalized for parenteral antibiotic therapy and prompt uterine evacuation. Bacteremia is more common with septic abortion than with other pelvic infections: septic shock and adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) may result.48 Management of severe sepsis requires early aggressive volume resuscitation, eradication of the infection and supportive care for the cardiovascular system and other involved organ systemseradication of the infection and supportive care for the cardiovascular system and other involved organ systems.8, 56

For a detailed review of the management of severe sepsis, the reader is referred to the publications of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign, an international collaborative which presently includes 30 organizations worldwide. The campaign has been developing expert evidence-based recommendations for more than a decade.57

Eradicating the infection

Blood cultures should be drawn, urine, and cervical cultures should be taken, and high-dose broad-spectrum antibioticsshould be begun intravenously. An endometrial biopsy specimen or tissue obtained at uterine aspiration provides a better specimen for culture than does cervical discharge. Examination of the gram-stained material can guide early management.

One time-honored regimen for severe pelvic sepsis is penicillin (5 million units intravenously [IV] every 6 hours) or ampicillin (2 g IV every 6 hours) combined with gentamicin (2 mg/kg loading dose, followed by 1.5 mg/kg every 8 hours or 5 mg/kg every 24 hours depending on blood levels and renal status). Either clindamycin (900 mg IV every 8 hours) or metranidazole (15 mg/kg initially followed by 7.5 mg/kg every 8 hours) is added. Rapid administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics is key to ensuring a favorable outcome.

Emptying the uterus

Remaining pregnancy tissue must be evacuated without delay as soon as antibiotic therapy and fluid resuscitation are begun. Hesitation of physicians to evacuate the uterus because of the poor condition of the patient is a common theme in fatal septic abortion in the United States.7 Vacuum curettage is readily accomplished with the patient under local anesthesia with minimal intravenous sedation, and if necessary, this can be performed in an intensive care unit bed. A retained fetus from midtrimester abortion poses a special challenge. The uterus usually can be readily evacuated by a curettage procedure, facilitated by ultrasound guidance, if a practitioner experienced with midtrimester dilation and evacuation abortions is available. Otherwise, a medical means for uterine evacuation is needed. Although little information is available about its use in the context of septic abortion, misoprostol, a prostaglandin E1 analogue widely used for induction of abortion in the first and second trimesters, is likely the drug of choice for this purpose. Misoprostol has fewer side effects than the older prostaglandins and is inexpensive, stable at room temperature, and widely available.58 Vaginal or sublingual doses of 400 μg at 3 hourly intervals are highly effective for inducing abortion in the midtrimester.59

Alternatively, high-dose oxytocin can be used. Fifty units of oxytocin is given in 500 mL of 5% dextrose and normal saline solution over a 3-hour period (approximately 278 mU/min). This is followed by a 1-hour rest and repeated, adding 50 additional units to the next 500-mL infusion, and continuing with 3 hours of infusion and 1 hour of rest. This is repeated until the patient aborts or a final solution of 300 U oxytocin in 500 mL is reached (1667 mU/min).60 If none of these means is available, another option is a metreurynter: A Foley catheter is placed in the lower uterus and the balloon inflated to 50–75 mL. One kilogram of traction from an orthopedic weight at the foot of the bed is then attached to the catheter. This dilates the cervix and stimulates contractions.61

The role of laparotomy

Laparotomy will be needed if the patient does not respond to uterine evacuation and adequate medical therapy. Other indications are uterine perforation with suspected bowel injury, pelvic abscess, and clostridial myometritis.50 In a clinically stable patient diagnostic laparoscopy can be undertaken to evaluate for possible uterine perforation resulting in injury to adjacent organs such as bowel or bladder. Although ultrasound-guided percutaneous needle aspiration of pelvic abscesses is practiced, in critically ill women with severe postabortal sepsis, hysterectomy will likely be needed in addition to drainage of any abscess. A discolored, woody appearance of the uterus and adnexa, suspected clostridial sepsis, crepitation in the pelvic tissues, and radiographic evidence of air within the uterine wall, are indications for total hysterectomy and possible removal of both adnexae. Operative cultures should be obtained. Copious irrigation of purulent material and drainage of the peritoneal cavity with closed suction systems is advised. Diversion of the fecal stream by enterostomy is needed if there is bowel injury.

Abdominal closure should be by interrupted internal stays (Smead-Jones or similar) or a running mass ligature including peritoneum, rectus muscles, and rectus fascia. The subcutaneum and skin are left open with sutures placed for a delayed primary closure, and the wound is packed.

Supportive care

Patients with severe sepsis and septic shock should be managed in intensive care settings in collaboration with physicians and nurses trained in critical care medicine. However, care should be initiated as soon as possible and not delayed until transport is accomplished. Principles of management are aggressive source control with antibiotics and early hemodynamic resuscitation. Cardiovascular support attempts to restore tissue perfusion with fluid management and inotropic therapy. Principles of management of postabortal septic shock are not different from those of other causes, other than the need to ensure evacuation of the uterus.

First, respiratory status must be stabilized and next perfusion should be restored. Intubation and mechanical ventilation may be necessary as hypoxemia, which may develop as a result of inadequate cardiac output from septic shock or adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

Supplemental oxygen should be administered and oxygenation should be monitored with pulse oximetry. Chest radiographs and arterial blood analysis can be used to help make the diagnosis of ARDS.

Septic shock is a combination of vasoplegia and relative hypovolemia from an endothelial leak state. Hypovolemia needs to be treated aggressively as it results in decreased tissue perfusion. This approach is known as early goal directed therapy and it has been shown to improve mortality when initiated within the first 6 hours of presentation.55 Central venous catheters (CVC) and central venous oxyhemoglobin saturation (ScvO2) should be used if available. Treatment guided by the use of CVC and ScvO2 has been shown to decrease mortality in the setting of septic shock. Goals of CVP of 8-12 mmHg and ScvO2 >70% should be used.56 Mean arterial pressure of >65 mmHg, urine output of >0.5 mL/kg per hour, and lactate clearance are clinical signs of reperfusion. These measures can be useful in low resource settings when central monitoring is not readily accessible. Fluid should be administered in rapid large boluses of 500–1000 ml and patients will likely require at least 2 liters and as much as 5 liters of crystalloid in the first 6 hours. Hydroxyethyl starches (HES) are not recommended for fluid resuscitation in treating sepsis.57 Administration of appropriately targeted antibiotics within the first hour of presentation has also been shown to improve outcomes.

Vasopressors are added if the patient remains hypotensive despite adequate volume resuscitation or in patients who develop cardiogenic pulmonary edema limiting volume resuscitation efforts. Norepinephrine should be the first line agent used for the management of refractory hypotension in the setting of septic shock. Norepinephrine is used at 2–20 µg/min. Epinephrine is added or substituted for norepinephrine when an additional agent is needed to maintain adequate blood pressure. Dopamine is no longer routinely recommended.57 In a recent systematic review of randomized controlled trials of dopamine versus norepinephrine there was no statistically significant in-hospital or 28-day mortality among patients with septic shock.62 Dopamine, however, is associated with an increased risk for arrhythmia.63 Inotropic therapy with dobutamine is recommended for sepsis patients with low cardiac output in the presence of adequate fluid resuscitation. Anemia should be corrected with packed red blood cells to a hemoglobin of 7 g/dL. Fresh frozen plasma, platelets or cryoprecipitate should be used only when there is clinical or laboratory evidence of coagulopathy.64

Management of pulmonary complications

ARDS will develop in 25–50% of patients with septic shock.52 The cornerstone of treatment in the management of ARDS is low tidal ventilation to prevent further lung injury. When using mechanical ventilation, the tidal volume should be set to 6 mL/kg (calculated on ideal body weight) with goal plateau pressures less than 30. The principle of limiting tidal volume is to avoid further volume trauma to the lung and the need for restricting plateau pressure is to avoid barotrauma.

Adjunctive therapies

High-dose corticosteriod therapy is no longer recommended, after two randomized trials failed to find benefit.65, 66 Compared to placebo, hydrocortisone resulted in a more rapid reversal of shock, but because of increased secondary infections, the mortality at 28 days was not improved.67 External cooling (to a core body temperature of 36.5–37°C) in patients with septic shock requiring vasopressors, ventilation and sedation may have a mortality benefit68 but this practice requires further investigation before it becomes standard of care.

FATAL INFECTION WITH CLOSTRIDIUM SORDELLII

Nine deaths have occurred in the US, and one in Canada, from Clostridium sordellii sepsis in women who had early abortion induced with mifepristone and vaginal misoprostol. The rate of deaths from C. sordellii sepsis with medical abortion in the US is estimated as 0.58 per 100,000 medical abortions.69This organism has also caused a number of deaths in childbirth, spontaneous abortion, in users of injected illegal drugs, and in trauma or surgery.70 The patients presented in an unusual way, with severe pelvic pain, no fever, but with severe hemoconcentration producing a very high hematocrit and a leukemoid reaction, and then rapidly developed shock associated with massive edema. The patients all died despite vigorous and prompt hospital treatment, including hysterectomy. Death appeared attributable to a lethal toxin elaborated by this bacterium.69 Whether earlier diagnosis based on this unique presentation, confirmed by Gram stain of an endometrial biopsy showing the characteristic Gram positive rods and treated with hysterectomy would improve outcomes, is unknown.

CONCLUSIONS

Death and serious complications from abortion-related infection are almost entirely avoidable. Unfortunately, prevention of death from abortion remains more a political than a medical problem. Although leaders in international health have repeatedly drawn attention to abortion complications and maternal mortality, many governments and health care agencies still lack the moral courage to confront the problem.69 For health professionals, the ethical issues have been clearly defined: we have a duty “to affirm our own commitment to health values. We are obligated to put health first, to do so by respecting the best available scientific evidence, and to be frank when we put aside such evidence for other considerations, be they moral, or religious, or economic, or simply expedient.”71, 72

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Sajid Shahul, MD, Instructor in Anesthesiology and Critical Care at Harvard Medical School and the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, MA for his critical reading of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

Stedman’s Medical Dictionary. p 4, 21st ed. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1966 |

|

Last JM: Scope and methods of prevention. In Last JM (ed): Maxcy-Rosenau Public Health and Preventive Medicine. pp 3, 4 11th ed. New York, Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1980 |

|

Jewett JF: Septic induced abortion. N Engl J Med 289:748, 1973 |

|

Cates W Jr, Rochat RW, Smith JC, et al: Trends in national abortion mortality, United States, 1940–74: Implications for prevention of future abortion deaths. Adv Planned Parenthood 11:106, 1976 |

|

Cates W Jr, Rochat RW: Illegal abortion in the United States 1972–74. Fam Plann Perspect 8:86, 1976 |

|

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Abortion surveillance: preliminary data— U.S., 1992 MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 43:42, 1994 |

|

Grimes DA, Cates W Jr, Selik RM: Fatal septic abortion in the United States, 1975–77. Obstet Gynecol 57:739, 1981 |

|

Faro S, Pearlman M: Infections and Abortion. pp 41, 50 New York, Elsevier, 1992 |

|

Cates W Jr, Rochat RW, Grimes DA, et al: Legalized abortion: Effect on national trends of maternal and abortion related mortality (1940 through 1976). Am J Obstet Gynecol 132:211, 1978 |

|

Pazol, K,.Creanga, A. Burley, K. Hayes, B. Jamieson, D. Abortion Surveillance-United States, 2010. MMWR 2013;62: No. SS-08 (1-44). |

|

Council on Scientific Affairs, American Medical Association: Induced termination of pregnancy before and after Roe v. Wade: Trends in the mortality and morbidity of women JAMA 268:3231, 1992 |

|

Hakim-Elahi E, Tovell HMM, Burnhill MS: Complications of first-trimester abortion: A report of 170,000 cases. Obstet Gynecol 76:129, 1990 |

|

Finer LB, Zolna MR: Shifts in intended and unintended pregnancies in the United States 2001-2008. American Journal of Public Health: February 2014, Vol. 104, No. S1, pp. S43-S48 |

|

Guttmacher Institute [Internet] New York: Guttmacher Institute; c2014. [Updated 2014 May 1; cited 2014 May 4]. State policies in brief: an overview of abortion laws Available from: http://www.guttmacher.org/statecenter/spibs/spib_OAL.pdf |

|

Grimes DA, Forrest JD, Kirkman AL et al: An epidemic of antiabortion violence in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991 Nov;165(5 Pt 1):1263-8. |

|

Grimes DA: Clinicians who provide abortions: the thinning ranks. Obstet Gynecol. 1992 Oct;80(4):719-23. |

|

Coles MS, Koenigs LP. Self-induced medical abortion in an adolescent. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. Apr 2007;20(2):93-95 |

|

Jones RK. How commonly do US abortion patients report attempts to self-induce? Am J Obstet Gynecol. Jan 2011;204(1):23 e21-24 |

|

Saultes TA, Devita D, Heiner JD. The back alley revisited: sepsis after attempted self-induced abortion. West J Emerg Med. Nov 2009;10(4):278-280 |

|

Sedgh G, Singh S, Shah IH et al: Induced abortion: incidence and trends worldwide from 1995 to 2008. Lancet. 2012 Jan 18. [Epub ahead of print] |

|

Parfitt T: Russia set to tighten restrictions on abortion. Lancet. 2011 Oct 8;378(9799):1288. |

|

Singh S. Hospital admissions resulting from unsafe abortion: estimates from 13 developing countries. Lancet, 2006, 369(9550):1887-1892. |

|

World Health Organization, Maternal and Child Health Unit and Family Planning, Division of Family Health: Unsafe Abortion: Global and regional estimates of the incidence of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2008. 6nd ed. Geneva, WHO, 2011 |

|

Bernstein PS, Rosenfield A: Abortion and maternal health. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 63(Suppl 1):S115, 21998 |

|

Rasch V, Muhammad H, Urassa E, et al: Self-reports of induced abortion: An empathetic setting can improve the quality of data. Am J Public Health 90:1141, 2000 |

|

Liskin L: Complications of abortion in developing countries. Popul Rep F 7:105, 1980 |

|

Toure B, Thonneau P, Cantrelle P, et al: Level and causes of maternal morality in Guinea (West Africa). Int J Gynecol Obstet 37:89, 1992 |

|

Kampikaho A, Irwig IM: Incidence and causes of maternal mortality in five Kampala hospitals, 1980–1986. East Afr Med J 68:625, 1991 |

|

Okonofua FE, Onwudiegwu U, Odunsi OA: Illegal induced abortion: A study of 74 cases in Ile-Ife, Nigeria. Trop Doct 22:75, 1992 |

|

Konje JC, Obisesan KA, Ladipo OA: Health and economic consequences of septic induced abortion. Int J Obstet Gynecol 37:193, 1992 |

|

Fauveau V, Koenig MA, Chakraborty J, et al: Causes of maternal mortality in rural Bangladesh, 1976–85. Bull World Health Organ 66:643, 1988 |

|

Pardo F, Uriza G: y el Federacion Colombiano de Sociedades de Obstetricia y Ginecologia: Estudio de morbilidad y mortalidad por aborto en 36 institucions de Bolivia, Colombia, Peru, y Venezuela. Rev Colombiana Obstet Ginecol 42:287, 1991 |

|

Laguardia KD, Rotholz MV, Belfort P: A 10-year review of maternal mortality in a municipal hospital in Rio de Janeiro: A cause for concern. Obstet Gynecol 75:27, 1990 |

|

Verma K, Thomas A, Sharma A, et al: Maternal mortality in rural India: A hospital-based, 10-year retrospective analysis. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 27:183, 2001 |

|

Barot, S. Unsafe Abortion: The Missing Link in Global Efforts to Improve Maternal Health. Guttmacher Policy Review, Spring 2011 Volume 14, Number 2: 1-6. |

|

Sai FT, Nassim J: The need for a reproductive health approach. Int J Gynecol Obstet 3(Suppl):103, 1989 |

|

Villarreal J: Commentary on unwanted pregnancy, induced abortion and professional ethics. A concerned physician’s point of view Int J Gynecol Obstet 3(Suppl):351, 1989 |

|

Mosher WD: Fertility and family planning in the United States: Insights from the National Survey of Family Growth. Fam Plann Perspect 20:207, 1988 |

|

Zabin LS, Clark SD: Why the delay? A study of teenage family planning clinic patients Fam Plann Perspect 13:205, 1981 |

|

Stephenson P, Wagner M, Badea M, et al: Commentary: The public health consequences of restricted induced abortion—Lessons from Romania. Am J Public Health 82:1328, 1992 |

|

Appendix Table 3. Sharing Responsibility: Women, Society and Abortion Worldwide. p 53, New York, The Alan Guttmacher Institute, 1999 |

|

Bhandari A, Gordon M, Shakya G: Reducing maternal mortality in Nepal. BJOG. 2011 Sep;118 Suppl 2:26-30. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03109.x. |

|

Anon. Facts on Induced Abortion Worldwide. In Brief. Alan Guttmacher Institute, New York, NY, January 2012 |

|

Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs, American Medical Association: Mandatory parental consent to abortion. JAMA 269:82, 1993 |

|

Paul M, Lichtenberg ES, Borgatta L, et al: A Clinician’s Guide to Medical and Surgical Abortion. pp 25, 228 New York, Churchill Livingstone, 1999 |

|

Ludmir J, Stubblefield PG: Pregnancy termination. In Gabbe SG, Niebyl JR, Simpson JL (eds): Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. pp 622, 650 4th ed.. New York, Churchill Livingstone, 2002 |

|

Sawaya GF, Grady D, Kerlikowske K, et al: Antibiotics at the time of induced abortion: The case for universal prophylaxis based on a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol 87:884, 1996 |

|

Polgar S, Fried ES: The bad old days: Clandestine abortions among the poor in New York City before liberalization of the abortion law. Fam Plann Perspect 8:125, 1976 |

|

Burnhill MS: Treatment of women who have undergone chemically induced abortion. J Reprod Med 30:610, 1985 |

|

Sweet RL, Gibbs RS: Infectious Diseases of the Female Genital Tract. pp 229, 240 2nd ed. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1990 |

|

Hakim-Elahi E, Tovell HMM, Burnhill MS: Complications of first-trimester abortion: A report of 170,000 cases. Obstet Gynecol 76:129, 1990 |

|

Burkman RT, Atienza MF, King TM: Culture and treatment results in endometritis following elective abortion. Am J Obstet Gynecol 128:556, 1977 |

|

Fisher, M, Bhatnagar, J, Guarner, J, et al. Fatal toxic shock syndrome associated with Clostridium sordellii after medical abortion. N Eng J Med 2005;353:2352 |

|

Centers for Disease Control: Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines, 2010. http://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/2010/pid.htm-regimens.htm, accessed January 26, 2011. |

|

Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S et al: Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2001 Nov 8;345(19):1368-77. |

|

Duff P: Septic shock. In Pauerstein CJ (ed): Clinical Obstetrics. pp 785, 802 New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1987 |

|

Dellinger, RP, Levy, MM, Rhodes, A, Annane, D, Gerlach, H, Opal, SM, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock:2012. Crit Care Med 2013;41:580-637) |

|

Goldberg AB, Greenberg MB, Darney PD: Misoprostol and pregnancy. N Engl J Med 344:38, 2001 |

|

von Hertzen H, Piaggio G, Wojdyla D et al: Comparison of vaginal and sublingual misoprostol for second trimester abortion:randomized controlled equivalence trial. Hum Reprod. 2009 Jan;24(1):106-12. Epub 2008 Sep 14. |

|

Winkler CL, Gray SE, Hauth JC, et al: Mid second trimester labor induction: Concentrated oxytocin compared with prostaglandin E2 vaginal suppositories. Obstet Gynecol 77:297, 1991 |

|

Boulvain M, Kelly A, Lohse C et al: Mechanical methods for induction of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(4):CD001233. |

|

Vasu TS, Cavallazzi R, Hirani A et al: Norephinephrine or Dopamine for Septic Shock: A Systematic Review of Randomized Clinical Trials.J Intensive Care Med. 2011 Mar 24. |

|

Havel C, Arrich J, Losert H et al: Vasopressors for hypotensive shock. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 May 11;(5):CD003709. |

|

Practice Guidelines for blood component therapy: A report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Blood Component Therapy. Anesthesiology. 1996 Mar;84(3):732-47. |

|

Nathanson C, Hoffman WD, Parrillo JE: Septic shock: The cardiovascular abnormality and therapy. J Cardiothorac Anesth 3:215, 1989 |

|

Bone RC, Fisher CJ, Clemmer TP, et al and the Methylprednisolone Sepsis Study GroupA controlled clinical trial of high-dose methylprednisolone in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med 317:653, 1987 |

|

Sprung CL, Annane D, Didier K, Moreno R, Singer M, Freivogel K, et al. Hydrocortisone therapy for patients with septic shock, N. Engl J Med 2008;358:111-124. |

|

Kortgen A, Niederprum P, Bauer M. Implementation of an evidence-based “standard operating procedure” and outcome in septic shock. Crit Care Med 2006; 34:943. |

|

Meites E, Zane S, Gould C: Fatal Clostridium sordellii infections after medical abortions. N Engl J Med. 2010 Sep 30;363(14):1382-3. |

|

Aldape MJ,Bryant AE, Stevens DL. Clostridium sordelli infection: epidemiology, clinical findings, and current perspectives on diagnosis and treatment. Clin Infect Dis 2006;43:1436 |

|

Rosenfield A, Maine D: Maternal mortality—A neglected tragedy. Where is the M in MCH? Lancet 2:83, 1985 |

|

Susser M: Induced abortion and health as a value. Am J Public Health 82:1323, 1992 |