Use and Effectiveness of Barrier and Spermicidal Contraceptive Methods

Authors

INTRODUCTION

The prevention of pregnancy is an integral part of modern medical practice and is of major public health interest. In 2012, approximately 85 million women worldwide experienced unintended pregnancies.1 Methods for controlling fertility are necessary and desired. Traditionally, the practice of family planning centered almost exclusively on the prevention of unwanted conception. The goal of modern family planning has shifted towards providing more complete women’s reproductive health, providing women with effective contraceptives with consideration of on-contraceptive benefits and lifestyle advantages of different methods.2 In particular, family planning has the ability to address the dual threats of unintended pregnancy and prevention of sexually transmitted infections. In 2014, the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Office of Population Affairs included sexually transmitting infection (STI)/HIV testing, treatment, and prevention as a core component of family planning care.3

There are over 20 diseases that may be acquired during sexual relations.4 From an infectious epidemiology perspective, at the time of coitus, a person is potentially exposed to the STI status of all previous mates of his or her current consort. Theoretically, during a single instance of unprotected coitus, a woman could become pregnant and be infected with all STIs. Disparities exist in the acquisition of STIs, with women more susceptible than men to HIV, as well as other infections. Several factors contribute to this inequality; biological factors include differences in reproductive anatomy predisposing women to higher rates of infection, and social factors include problems in controlling the timing of intercourse, issues with partner infidelity, and gender inequality.5

The widespread dissemination of STIs including HIV/AIDS requires intervention by policymakers, health care providers, and patients alike. In the United States, there are approximately 20 million new STI infections annually, with the annual incidence of gonorrhoea and chlamydia on the rise.6 Worldwide, approximately 1 million STIs are acquired daily.7 In addition to many STIs having their own reproductive health consequences, coinfection with other STIs has been found to greatly facilitate HIV transmission.8, 9, 10 As of 2014, an estimated 36.9 million people were living with HIV worldwide. Over the last 15 years, the rate of individuals newly infected with HIV has slowed, however, approximately 2 million people are newly infected each year.11 Given concerns regarding long-term consequences of STI infections and facilitated transmission, interest in contraceptives offering dual protection from unintended pregnancy and STI acquisition has increased.12, 13 Anxiety about the magnitude of the progression of HIV and STI infections has motivated even some Catholic authorities, always in opposition to contraception, to consent to their use to some extent.14

Barrier contraceptives were long considered the best way of providing dual protection; however, this protection was not absolute.15, 16 Increased interest in dual protection has led to re-evaluation of the social and public health impact of mechanical and chemical contraceptives, and pushed for the development of more effective and novel dual protection approaches. Because of the difficulty of carrying field studies in the United States (e.g. cost, reluctant very movable population, liability concerns related to side effects and contraceptive failures, not always related to the use of the product being tested), domestic data on new contraceptives are often scarce. Development of new contraceptives and products that are safe, effective, and acceptable to consumers is a long, tedious, and arduous process, usually taking decades. Though development and testing of such methods is underway, barrier methods remain vitally important in helping mitigate the impact of the health crisis caused by HIV and other STIs. They continue to be widely available, and are often the most accessible option for women desiring dual protection.

CHARACTERISTICS OF BARRIER METHODS AND DETERMINANTS OF CONTRACEPTIVE EFFECTIVENESS

Barrier contraceptives are devices that physically prevent dissemination of sperm in the vagina, blocking the access of spermatozoa to the upper genital tract. Spermicides are pharmaceutical agents containing chemicals that kill or incapacitate sperm administered vaginally in a vehicle (gel, foam, cream, suppository, or film).17 Table 1 lists the common physical and chemical barrier methods of contraception. Barrier and spermicidal methods of contraception are coitus-dependent; all are temporally associated with sexual intercourse. All are female-dependent methods, except for the male condom. Barrier methods and spermicides may be used alone or in combination with one another. Spermicides are often used in conjunction with barrier methods.

Table 1. Barrier contraceptives and spermicides

| Physical barrier methods |

| Male condom |

| Female condom |

| Diaphragm |

| Cervical cap/Lea’s shield |

| Contraceptive vaginal sponge |

| Chemical methods |

| Spermicidal gels, jellies, creams |

| Vaginal foams, films, suppositories, tablets |

Although there are marked differences among various barrier methods of contraception, there are also some similarities. They are intimately associated with the users' sexuality and sexual behavior. Each sexual encounter provides a unique situation in which the partners must decide whether to use the method. One or both partners must make a decision and take action before every episode of sexual intercourse. Therefore, barrier contraceptives demand substantial motivation and necessitate cooperation from the partner.

The decision to comply with a contraceptive method depends on the perceived risk of becoming pregnant, the desire to avoid pregnancy, and numerous other factors, such as the need for confidentiality, side effects, cost, self-efficacy, knowledge of how a contraceptive works, and noncontraceptive benefits. For many people, the successful and consistent use of barrier methods necessitates a change in sexual behavior.2, 18

Safety and effectiveness of barrier methods

Barrier contraceptives are very safe. They are used inconsistently more often than noncoitus-dependent methods. Barrier contraceptive methods continue to be the primarily recommended method for the prevention of STDs and HIV, making them important for ensuring reproductive health. Finally, barrier contraceptives make an important contribution to family planning and public health because they are safe, have no systemic side effects or risks, are effective when used properly, and play a prominent role in the prevention of STDs.19, 20

Barrier methods are reputed to be less effective than other methods. However, they have a significant historical role in the process of making contraception universally available.21 Most of them can be distributed easily through community-based organizations and women's health maintenance groups, and in developing countries by social marketing programs through existing commercial outlets. They extend the accessibility of reliable contraceptives to a greater number of people than ordinarily would be reached by the formal healthcare system. In particular, the male condom has been shown to reduce the spread of HIV infections in large populations, translating into significant public health benefits.22, 23

There are two common measures of how a contraceptive works: efficacy with perfect use (how it performs with correct and consistent use) and efficacy with typical use (which includes both incorrect and inconsistent use).2 Overall efficacy depends on many factors: frequency of intercourse, fecundity of the users, how the method is used, and the quality of the product. But more than for other birth-control methods, the efficacy of barrier methods depends on how well couples use them.24 A method that is rated as less effective could actually be more effective for a particular couple if they use it correctly and regularly. Most contraceptive failures can be ascribed to inadequate compliance or misuse of the prescribed regimen. Barrier contraceptives and condoms used correctly at every episode of sexual intercourse are very effective in preventing pregnancy.2, 25

The reported range of failure or pregnancy rates for barrier methods is vast, from 2 to 32% of women experiencing an unintended pregnancy in the first years of use, depending on the study, the method, and the population.2, 25 The best results are shown in clinical studies using exacting patient selection with considerable input of resources to diminish follow-up losses, reinforce instructions, counter weak motivation, and increase compliance by encouraging correct and consistent use, thus increasing the reliability of the data. Couples available for the follow-up required for clinical studies are often not representative of patients most likely to benefit from them. Thus, the results of most clinical studies tend to be better than the actual performance of any given method during general population use, when a method is more subject to human error and inconsistent behavior. Clinical studies of contraceptives are subject to investigator and participant biases, and study endpoint of use effectiveness should be viewed with caution. Measured thus imperfectly, the generally credited failure rates of various contraceptive methods are shown in Table 2. The physician prescribing a contraceptive should take into consideration the patient's lifestyle and preferences and must be nonjudgmental and unbiased in discussing the benefits and disadvantages of the methods available. Occasionally, physicians are criticized for their involvement in providing contraceptive advice, education, and prescription; however, more criticism is deserved for physicians who ignore an opportunity when contraceptive advice was pertinent, needed, and even requested.

Table 2. Percentage of women experiencing an unintended pregnancy in the first year of use, United States

Method | Typical use (%) | Perfect use (%) |

No method | 85 | 85 |

Spermicides | 28 | 18 |

Withdrawal | 27 | 4 |

Fertility-awareness based methods | 24 | |

Standard days method | 5 | |

Two day method | 4 | |

Ovulation method | 3 | |

Diaphragm | 12 | 6 |

| ||

Nulliparous women | 16 | 9 |

Parous women | 32 | 20 |

| ||

Female | 21 | 5 |

Male | 15 | 2 |

| ||

Combined pill and minipill | 8 | 0.3 |

Evra patch | 8 | 0.3 |

NuvaRing | 8 | 0.3 |

Depo-Provera | 3 | 0.3 |

| ||

ParaGard (copper T) | 0.8 | 0.6 |

Mirena (levonorgestrel) | 0.2 | 0.2 |

Implant | 0.05 | 0.05 |

Female sterilization | 0.5 | 0.5 |

Male sterilization | 0.15 | 0.1 |

Modified from: Trussell J. Contraceptive failure in the United States. Contraception 2011;83(5):397-404.

Barrier methods' effectiveness as contraceptives and in STD and HIV prevention is enhanced by their consistent and correct use. Frequently, these methods are overlooked and not prescribed; more often, people may fail to use them, change to other methods, or abandon their use and switch to no contraception, resulting in more user failures.26 Conversely, a desire for the privacy offered by some barrier methods made them more acceptable, especially to women who are not willing to admit their sexual activity or will not consult a physician and be examined without having a health problem. For many potential users, the imminence of coitus and the fear of pregnancy are the only stimuli sufficiently powerful to arouse interest in contraception. Most barrier contraceptives are available over-the-counter without a prescription, do not necessitate a physical examination, and, for some people, in certain particular circumstances, may be the best or only effective method available. The correct and consistent use of barrier and spermicidal methods of contraception is determined by the complex interaction of the inherent attributes of the method, user characteristics, and situation. Method attributes include the extent of interference with sexual spontaneity and enjoyment, the amount of partner's cooperation required, and the ability of the method to protect against unwanted pregnancy, STDs, and HIV. User characteristics include motivation to avoid unintended pregnancy, fear of contracting an STD, ability to plan, cultural and religious attitudes regarding sexuality and contraception to which she is subjected, comfort with sexuality, and previous contraceptive experience. Characteristics of the relationship, stage of reproductive career, and previous sexual experiences are important situational influences. User preferences are critical considerations for practitioners recommending a contraceptive method, especially one that requires motivation for proper use.27

Obtaining valid estimates of the reduction in STD transmission conferred by barrier contraceptive use is challenging,28, 29, 30 but it is clear that condoms provide significant protection from STDs, even with imperfect use.22, 23, 31 Other barrier and spermicide methods are reported to provide protection against STDs and pelvic inflammatory disease.32, 33, 34 Their use has been associated with lower rates of cervical cancer than other methods of contraception.35, 36 Women who never use barrier methods have twice the chance of having cancer of the cervix develop.37 Barrier methods also contribute to the prevention of infertility, likely secondary to their protection from pelvic infections.33, 34 A rare problem associated with the use of certain barrier contraceptives is toxic shock syndrome (TSS), an uncommon but potentially fatal systemic infection with Staphylococcus aureus. Occurrences of TSS associated with the diaphragm and contraceptive sponge have been reported.38 However, the actual risk is exceedingly rare, with the annual incidence of TSS from any etiology of less than 1 per 100,000.39

Choice of contraceptive methods

Although their characteristics vary widely, each contraceptive method in use today has limitations. As such, there are currently gaps in women's ability to control fertility safely, effectively, and in culturally acceptable ways throughout their reproductive lives. The consistent use of barrier contraception depends on a woman's perception of her risks of pregnancy and sexually transmitted infection with each act of intercourse, and these risks may not be equally important to every woman.2, 40 Although a woman's fertile period is limited, no woman knows exactly when ovulation occurs, so women should be advised to use contraception at all times. A woman is fertile only a few days every menstrual cycle. The chance of pregnancy after any one act of sexual intercourse has been estimated to be approximately 3–4.5%.41

The main considerations against the acceptability of barrier contraceptives are the necessity for touching the genitalia, messiness, storage, resupply, disposal, and direct relation to coitus. Some methods are bulky and difficult to store, carry, and use discreetly. In addition, planning and motivation are required to ensure consistent use. All these challenges occur to some extent with most users in most cultures.42

Contraceptive methods are complementary, not competitive. Each method offers a different balance of advantages and disadvantages, and the physician should be ready to advise or prescribe another method when the patient is not satisfied with the current one. The prescription or fitting of a contraceptive device should always be accompanied by thorough instructions for its proper use. Never assume the patient understands the correct use of the method chosen, and consider that the printed material for most contraceptives is usually above the level of literacy of the intended audience.43 Functional health literacy influences contraceptive understanding, attitudes, and behavior, and low literacy levels are a problem in family planning clinics.44, 45 Women with more education are better able to control their own sexuality. More education is associated with better health outcomes, a lower number of pregnancies, and lower infant and maternal morbidity and mortality, as well as higher life expectancy.

Reproductive health involves not only the prevention of unintended pregnancy but also of STDs, especially HIV. To increase the degree of prevention, it is appropriate under many circumstances to recommend simultaneous use of two contraceptive methods (e.g. systemic hormonal contraceptives or IUDs and condoms, or sterilization and condoms). In fact, dual method use is widely advocated and has been the subject of intensive research in recent years.12, 13, 15[46 It has been speculated that emphasizing the important advantage of disease prevention increases the acceptability of condoms and their consistency of use. Patients usually attach different priorities to preventing pregnancy or STDs, and these priorities may change over time and among relationships.2, 47, 48

GENERAL INDICATIONS FOR BARRIER METHODS

Barrier contraceptives are indicated for: (1) women in whom other forms of contraception are contraindicated; (2) women who prefer a reversible contraceptive method without hormonal effects or requiring implantation of a specialized device; (3) women seeking an interim method until hormonal or intrauterine contraception is initiated or sterilization is performed; (4) women during lactation and the puerperium, often as an adjunct to lactational methods; (5) women who elect to use barrier methods for infrequent episodes of intercourse; (6) women who plan to conceive in the near future; and (7) women at risk for sexually transmitted infection, who may elect to use barrier methods alone or in conjunction with another contraceptive method (dual method use).

MALE CONDOMS

The condom (also known as a prophylactic, rubber, sheath, or French letter) is the only widely available male method of contraception available besides coitus interruptus (withdrawal) and male sterilization. It is one of the oldest and most extensively used contraceptives. Variations of the condom have been used for thousands of years to prevent conception and infection; however, it was first formally described by anatomist/physician Gabriel Falloppio in the 16th century as a way to prevent syphilis.49 The worldwide upsurge of STDs as well as the unstoppable pandemic of HIV/AIDS contributed to dilute most of the reservations about condoms and its use held by society at large. Because of its excellent record of infection prevention and contraceptive protection, its availability, and its simplicity of use, the condom has become a cornerstone of family planning care. It offers protection against unintended pregnancy and serves as the greatest defense against STD transmission; its historical role in the prevention of STDs is unmatched by any other method of contraception.

Benefits and limitations

There is consistent clinical evidence from prospective studies of discordant couples, in which one partner is infected with HIV and the other not, that latex condoms used correctly during every act of sexual intercourse are very effective, not only in preventing unintended pregnancy, but also in HIV transmission.22, 23 When used correctly during each sexual act, condoms are very effective in preventing unintended pregnancies and STDs. In this dual capacity, condoms may be regarded as the contraceptive gold standard against which all other contraceptive methods might be compared. In strict comparison, most other contraceptive methods fall short, because of their lack of ability to prevent sexually transmitted infection. Consider the specifications for an ideal contraceptive: high effectiveness, safe, reversible, inexpensive, free from side effects, small and inconspicuous, aesthetically acceptable, self-administered, simple to use, requiring no special skills or professional intervention, easy to store and distribute, offers STD prevention, long shelf life, and use independent of sex. Male condoms answer with ease all those requirements except the last, although the last criterion presents a major hurdle in effectiveness.50 Additionally, condoms play an important role in rare cases in which women are hypersensitive (atopic allergy) to contact with semen.

Male condoms confer several benefits. They are widely available, easily obtainable, and reasonably inexpensive (even provided without charge by many family planning and STD clinics and some student health services). Condoms are frequently distributed through public health campaigns and programs, increasing their availability.51, 52 They do not require prescription or fitting. Condoms have virtually no contraindications or side effects, except in persons with preexisting allergies to latex rubber or lubricant.53, 54 Problems possibly related to being powdered with talc have been reported.55, 56 Condoms are inconspicuous. They are simple to use, and their use is easy to teach and understand, even by people with limited education. Condoms can be used for sporadic or unanticipated coitus, or by those who have infrequent intercourse. Condoms are a viable method for couples who wish to share the responsibility for contraception, as well as when immediate assurance of successful protection against conception is psychologically important to either partner. They are valuable as an interim method before hormonal contraception is initiated or intrauterine contraception is inserted or sterilization is performed. Table 3 lists the indications and contraindications for male condom use.

Table 3. Indications and contraindications for male condom use

| Indications | ||

| Male | Female | Both |

| Genital or penile disease, including active sexually transmitted infection | Contraindications to hormonal or intrauterine contraception | Uncertain partner fidelity |

| Sensitivity or allergy to vaginal secretions | As 'backup' method when use of other contraceptive methods (e.g. oral contraceptive or injectable) is suboptimal | Male contraceptive control preferred |

| Temporary use while awaiting vasectomy | Temporary use when initiating hormonal contraception, or awaiting intrauterine contraception or sterilization | Risk of sexually transmitted infection |

| Premature ejaculation | Genital tract infection, including active sexually transmitted infection | Spontaneous sexual encounter or infrequent intercourse |

|

| Vaginitis, including vaginitis under treatment | Active or suspected sexually transmitted infection |

|

| Desires assurance that semen was not released into vagina | History of inactive viral sexually transmitted infection |

|

| Aversion or allergy to contact with semen |

|

|

| Psychological, cultural, or religious conflict with personal use of contraception |

|

|

| Postpartum |

|

|

| ||

| CONTRAINDICATIONS | ||

| Allergy to latex in either partner | ||

| Either partner unable or unwilling to use condom consistently | ||

Modified from: Sobrero AJ Sciarra JJ: Contraception, In Cohn HP (ed): Current Therapy 1978, Baltimore, WB Saunders Company, 1978

Drawbacks or perceived negative attributes of the condom are its historic connection with illicit sex, promiscuity, and distrust of the partner's health.57 Like all barrier contraceptives, condoms necessitate persistent, recurrent motivation to achieve dependable protection against pregnancy and sexually transmitted infection. They must be used correctly at each sexual engagement. A commonly mentioned drawback is the need to interrupt intercourse for placement; however, couples may surmount this by making the placement of the condom part of the sexual experience.

Contraceptive effectiveness and protection against infection

Condoms are made of latex rubber, polyurethane, and natural membranes (Lamb's cecal pouch). Most commercially available condoms are made of latex rubber. They come in an astounding variety of shapes (e.g. blunt or with a reservoir tip, ribbed, speckled, peppered with dots, contoured, with a helix or spiral rib, with a loose pouch over the glans or the penile shaft). Condoms come in an assortment of colors, combinations of colors, even fluorescent, and they may be flavored. They come in different sizes: standard (170 mm long and 50 mm wide), long (30% longer), extra-large (45% larger), narrower (6%), and shorter (15%). They come as extra-strength and extra-thin. They may be lightly powdered or lubricated with silicone or a water-soluble spermicide or without spermicide, or a desensitizing product. Their variety seems to be limited only by the imagination of the manufacturers. Indications are that there is a market for such diversity and attesting to the contemporary losing of old social restraints about sexual intimacy. Usually, condoms are neatly rolled and packaged flat in paper, plastic, or aluminum foil. They have a long shelf-life, especially if they are protected from direct sunlight, heat, oily substances, and ozone, all of which contribute to rapid latex deterioration.

Effectiveness of the male condom is associated with user ability, sexual practices, propensity for breakage, and issues related to manufacturing. No studies demonstrate that condoms lubricated with a spermicide are more effective than unlubricated condoms in preventing pregnancy. Problems of slippage occur more often with lubricated than non-lubricated condoms. Regarding sexual practices, vigorous coitus appears to increase ruptures. Reported figures on the incidence of condom breakage/slippage range between 1 and 11% of uses, with the majority of studies evidence suggesting an incidence between 1.6 and 3.6% of coital acts.58, 59, 60, 61, 62

During manufacture, condoms must meet the stringent standards set by ASTM International and International Organization for Standardization (ISO). In conjunction with the ISO and multiple other international agencies, the World Heath Organization releases a manual describing the guidelines for ensuring quality condoms, including specifications for latex type, appropriate shelf lives, minimum bursting volumes and pressures, electronic testing for identification of microscopic holes, water leak tests, and even packaging specifications.63 In many countries, including the United States, condoms are imprinted with the date of manufacture or an expiration date. Aging is a major predictor for condom breakage, so patients must be advised to discard condoms when past their expiration date.64, 65 However, equally important are the manufacturer's packaging and storage procedures and the user's appropriate handling at the time of intercourse.66

Latex condoms theoretically form a continuous, impervious barrier to bacteria and viruses, though in reality, it is impossible for this barrier to be 100% impenetrable. One FDA study found that fluorescent polystyrene microspheres (110 nm) similar in diameter to the HIV virus (90–130 nm) could pass through 29 of 89 unlubricated latex condoms. The harsh physical conditions of the in vitro test under which the study was performed included 30 mL of a watery suspension of particles at a concentration 100 times that reported for the average normal human ejaculate (3 mL) under high pressure over 30 minutes. Based on the rigorous nature of study conditions, the authors acknowledge that their findings likely represent a worst-case scenario for the risk of fluid transfer with condoms, which is still at least 10,000 times better than not using a condom at all.67 Women who are partners of HIV-positive condom users are less likely to seroconvert than those whose partners did not use condoms.22, 23 A recent review of 25 studies with almost 11 thousand HIV serodiscordant heterosexual serodiscordant couples analysed showed that condoms reduced HIV transmission by more than 70% when used consistently.22

Most users of condoms are more worried about avoiding unwanted conception than preventing an STD; however, this important personal and public health aspect of barrier contraception should not be relegated to a secondary role. It is worthwhile to emphasize that the prevention of STDs may prevent future infertility33, 34 and cancer of the cervix.35, 36 Reasons for inconsistent condom use among 18–24 years old college students exemplified wide variations in perceived risk (for pregnancy and STIs), substitution for less effective alternatives (such as withdrawal), and priority of avoiding unpleasant side-effects (condom smell, decreased sensation) over prevention of pregnancy/STIs.68 Much contemporary research focuses on access to condoms and reasons for use and non-use in various domestic and foreign populations.69, 70, 71, 72

Nonoxynol-9 (N-9), the spermicide used in many lubricated condoms, causes release of a natural rubber latex protein that may increase the risk of allergic reaction in individuals with latex hypersensitivity.53, 73 Although theories suggest that latex condoms increase the risk of developing latex allergy, studies show that exposure to condoms does not increase the risk of subsequent latex allergy.74 For latex-sensitive persons, condoms with or without N-9 may cause an allergic reaction.75 However, overall latex allergy associated with barrier contraceptive use is rare.

Latex-free and deproteinized latex condoms are good alternatives for latex-allergic patients.76, 77 Male synthetic condoms are manufactured using a dipped process similar to latex condoms or a cut-and-seal process using a synthetic elastomeric film. They are less elastic and wider than latex condoms, making them less constrictive. Avanti (London International Group, London, U.K.) is a popular, commercially available synthetic male condom, FDA-approved in 1991. It is made from Duron, a thermoplastic polyester polyurethane, and it is straight-sided and reservoir-tipped. It is wider, approximately 64 mm when lying flat versus 52 mm for the standard latex condoms. Tactylon (Sensicon Corp., Vista, CA), another plastic condom produced by the dipping process from another synthetic elastomer, has been cleared by the FDA, but it is not found commercially. Three Tactylon models were manufactured (standard, baggy, and with a wider closed end of 80 mm) to allow greater comfort by diminishing glans constriction and to provide a more elastic, standard shape condom. Ezon (Mayer Laboratories, Oakland, CA) is another synthetic elastomeric condom, but it is not cleared by the FDA. It bears a unique design. Rather than being rolled on like latex condoms, Ezon is slipped onto the penis. Trojan Supra (Carter-Wallace Inc., New York, NY) is polyurethane male condom, FDA-approved and commercially available in the United States. It is somewhat larger than most condoms, measuring 189 mm long and 59 mm wide.78 According most reports, synthetic condoms break and slide more often than latex condoms.77, 79, 80, 81 A recent Cochrane review comparing latex-free and latex condoms reported that non-latex condoms are an acceptable alternative to latex condom use when indicated, despite higher rates of clinical breakage. The authors noted that the contraceptive efficacy of non-latex products needs further investigation.77

Natural membrane condoms made of lamb cecum are also available. They fit loosely on the penis and conduct more heat than latex condoms, supposedly providing more sensitivity during intercourse. Their thicknesses are variable but similar to that of rubber latex condoms (approximately 0.07–0.08 mm). They are considerably more expensive than their latex counterparts. These condoms must be kept moist to prevent cracking of the animal membrane, so they are packaged with water-based lubricant. Laboratory tests show that natural membrane condoms contain micropores that allow passage of HIV, hepatitis B virus, and herpes simplex virus, and thus they are not indicated for STD prevention. No use-effectiveness data are available on natural membrane condoms, but they have been shown to prevent the passage of sperm and are permitted by the FDA to be labelled for pregnancy prevention.78, 82

In recent years, much deserved attention has centered on the ability of N-9 to prevent HIV transmission. Disruption of the vaginal and upper reproductive tract epithelium by N-9 was demonstrated in animal and human studies.83, 84 Concern developed that N-9 actually increased HIV transmission, due to viral entry through microscopic lesions in the vaginal mucosa caused by the spermicidal agent. A 2003 World Health Organization report summarized the research findings on use of condoms with N-9 lubricant. The committee concluded that condoms with N-9 were not more effective than condoms alone in pregnancy prevention, and that such condoms should not be encouraged for use. Use of condoms with N-9, however, was better than using no condom at all. N-9 was found to increase the risk of HIV transmission in high-risk women, but it remains a contraceptive option for women at low risk of HIV infection.85

Some research suggests an association between male condom use and urinary tract infection (UTI) in females. Condoms lubricated with N-9 have been associated with an increased frequency of UTIs versus condoms without the spermicide,86 and others conclude that non-lubricated condoms are also associated with UTI.87

The first-year failure rates for male condoms with typical use is usually quoted as 15% in the United States.19 Data from the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth document a 17.4% pregnancy rate in the first year of condom use. Risk factors for condom failure included younger age, multiparity, non-Hispanic black race, and poverty.88 The contraceptive effectiveness of the condom is acknowledged to be less than that of oral contraceptives, hormonal injections, implantable contraceptives, and intrauterine contraception. However, condoms used consistently and correctly are highly effective at preventing pregnancy, with perfect-use failure rates of only 2%.19

Clinicians, counselors, educators, and public health advocates all serve as sources for encouraging proper condom use. All must be familiar with the instructions for condom use and be able to direct patients appropriately (Table 4).

Table 4. Instructions for proper male condom use

| For prevention of STD transmission, use condoms made of latex rather than natural membrane, except in cases of latex allergy |

| Do not use torn condoms, those in damaged packages, or those with signs of age (brittle, sticky, discolored, past expiration date) |

| Place the condom on the penis before it touches a partner's mouth, vagina, or anus |

| Place the condom on the penis when it is erect. Make sure you have the rim side up so you can unroll it all the way down to the base of the penis, before the penis comes in contact with a body opening |

| Leave a space at the tip of the condom to collect semen; remove air pockets in the space by pressing the air out towards the base |

| Use only water-based lubricants. Lubricants such as petroleum jelly, mineral oil, cold cream, vegetable oil, or other oils may damage the condom |

| Replace a broken condom immediately |

| After ejaculation and while the penis is still erect, withdraw the penis while holding the condom carefully against the base of the penis so that the condom remains in place |

| Do not reuse condoms |

Modified from: Fox CE. Clinician's Handbook of Preventive Services, 2nd edition. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1998

Although issues exist with consistent method use, the dual function role of male condoms in preventing pregnancy and sexually transmitted infection must be emphasized. Currently, the condom is the only widely available method providing dual protection, and this importance must be conveyed to users for promotion of individual and public health.

FEMALE CONDOM

The female condom offers female-controlled dual protection against STDs and pregnancy, and thus is an important recent development in barrier contraceptives. First introduced in Europe in 1992, they were first approved for use in the United States in 1993. The most widely available condoms internationally include:89

- FC2®(brand names include Reality, Protectiv, Femidom, Care) – manufactured by Female Health Company, Chicago, IL

- VA w.o.w.®(brand names include Reddy, V’Amour) – manufactured by Medtech Products Ltd, Chennai, India

- The Woman’s Condom (brand names include O’Lavie™) – manufactured by Dahua Medical Apparatus Company, Shanghai, China in conjunction with PATH, Seattle, Washington

- Phoenurse® – manufactured by Tianjin Condombao Medical Polyurethane Tech. Co. Ltd, Tianjin, China

- Cupid™ – manufactured by Cupid Ltd, Nashik, India.

The FC2® is currently the only US FDA approved female condom. New designs and updates continue to emerge and be tested.90, 91

In addition to the benefits of female control, female condoms carry the advantage that they can be inserted up to 8 hours prior to coitus.92, 93 Many female condoms are made of polyurethane, which is hypoallergenic, stronger, and more resistant to heat than latex condoms, and is not sensitive to oily lubricants or storage under conditions that would damage rubber latex condoms.94 The FC2® is made of nitrile (synthetic latex), which has similar properties.89

The female condom (Fig. 1) consists of a soft, medical-grade polyurethane (or similar) sheath open at one end and closed at the other. It has two flexible rings (often of the same material), one at each end. The external open ring is designed to stay outside the vagina, resting against the vulva. The inner ring, at the closed end of the sheath, is firmer and must be inserted into the vagina. The majority of female condoms are pre-lubricated with silicon-based lubricant (aside from the Woman’s Condom, which is packaged un-lubricated, and expands from a capsule once within the vagina). Insertion of a female condom is facilitated by squeezing the inner ring with one hand while separating the vulvar labia with the other as when inserting a tampon or a diaphragm. Care should be taken not to twist the sheath; otherwise, insertion of the penis will be impossible. The internal ring should be pushed beyond the pubic bone and as close as possible to the cervix. The internal ring, which is not incorporated into the wall of the condom, should not be removed. After intercourse, the open ring should be squeezed and twisted to keep the semen inside without spilling. The device is intended for single use.

The female condom is somewhat more expensive than its male counterpart. However, given the potential impact in reducing HIV infection afforded by a female-controlled method, some donor organizations have contracted with producers to provide the devices at low cost. These social campaigns have negotiated costs of less than one US dollar per device, and some studies indicate that such campaigns are cost-effective.95 Female condoms are also felt to be equally as effective as male condoms at preventing HIV and STI transmission,96 and theoretically may be more protective at preventing genital ulcer diseases given their coverage of the vulva and perineum.

Reuse of the female condom has been reported in many countries, especially those with limited resources. The general recommendation is to use a new condom for each act of intercourse, due to concerns for compromised structural integrity of the condom with handling and washing. Some studies examine the possibility of reuse of female condoms; most found that repeated cleansing of the condoms was associated with structural defects, but usually only after multiple washes.97, 98 In one study, devices were still within FDA standards for structural integrity after repeated washings.98 WHO does not recommend or promote reuse of the device, but acknowledging that access to new condoms may be limited in developing areas, has issued a protocol for the safe cleaning and handling of female condoms for reuse.99, 100

The contraceptive effectiveness of female condoms is similar to that of male condoms and other barrier methods.101, 102 First-year failure rates in the United States are estimated at 5 and 21%, for perfect and typical use, respectively.2 Most users consider the device acceptable, and widespread uptake of female condom use should prove possible with social marketing, directed counselling and increased availability in at-risk populations.103, 104, 105

The female condom offers major potential as a dual-function method, as its effectiveness at preventing pregnancy and sexually transmitted infection is similar to that of the widely accepted male condom. The female condom is a welcome addition to the contraceptive armamentarium. It is acceptable to women of many different cultures and provides its users with credible dual protection under female control.

CONTRACEPTIVE DIAPHRAGM

Invention of the contraceptive diaphragm is credited to the German gynecologist Wilhelm Mensinga, who described it in 1881.21 It was introduced in America in the early part of the 20th century by the illustrious feminist Margaret Sanger, who brought the diaphragm from Holland upon return from her self-imposed exile. It was popularized by her followers and the family planning movement she initiated as part of her efforts to liberate women from the burdens of undesired pregnancy. The vaginal diaphragm was the first highly effective method of contraception available to women. As such, and for more than 40 years until the advent of oral contraceptives and the intrauterine device, it was the backbone of the family planning movement in the US. The diaphragm was originally used by upper- and middle-class women who had not only the sophistication to recognize their sexual rights, but also the means and privacy to take advantage of them. It placed the contraceptive initiative and responsibility under the control of women. Important advantages of the diaphragm include moderate protection against sexually transmitted infections, lack of systemic side effects, cost-effectiveness, reversibility, and low maintenance, with requirement for only a single physician visit in most cases.106

The original Mensinga vaginal diaphragm consisted of a narrow, flat steel band, forming a ring. Vulcanized rubber completely covered the ring and closed the space, shaping a dome. This domed rubber cup, with no modifications except for improvements in the quality of the rubber and the ring, has remained virtually unchanged as an excellent female-controlled barrier contraceptive. Those constructed with rubber or latex rubber are sensitive to oily substances and lubricants. When properly fitted and placed, diaphragms ride diagonally in the vagina between its posterior fornix and the tissues on the back of the pubic arch.

Types of diaphragms

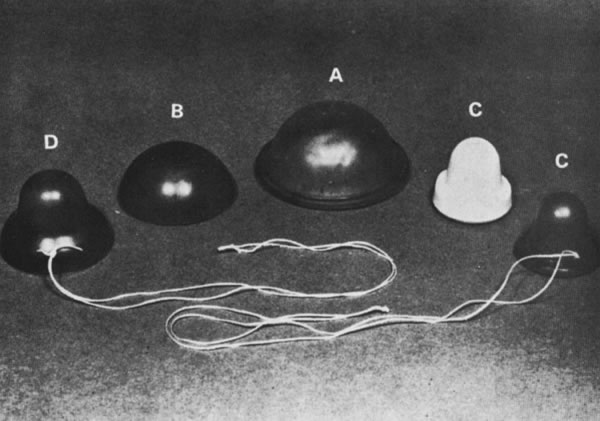

Diaphragms are available in three general types: coil spring, flat spring, and arcing spring (Fig. 2 and Table 5).106 Most are made of latex or rubber. The flat spring or Mensinga diaphragm allows lateral compression but has no frontal elasticity. The coil spring type has a ring made of coiled steel that permits good lateral as well as limited frontal elasticity. Flat and coil spring diaphragms form a straight line when compressed to insert them. Because of their construction, they offer only lateral elasticity. They are suitable for most women, and they fit well, even when there is moderate vaginal relaxation without cystocele. Arcing spring diaphragms come in two types. The hinged or 'bow-bend' diaphragm has in the core of its steel coil two semicircles of rigid steel that permit it to bending only in one position, forming a pointed arc. It is rigid in the anteroposterior axis and exerts strong lateral pressure. It cannot be fitted in most women with a retroverted uterus. The other arcing diaphragm is the All-Flex. The rim of this diaphragm forms an arch regardless of where it is compressed. It also offers some frontal elasticity. Most women find arcing diaphragms easier to insert because their curving assists in guiding it. They fit well, even in those vaginas with some relaxation or in the presence of a long cervix. The differences among them are only the type of ring and the degree of vaginal support they may offer and the ease of fitting and of insertion and removal by the user. For women with latex sensitivity, the arcing spring and coil spring types include a silicone-derived alternative. These silicone diaphragms are not available from pharmacies and must be ordered from the manufacturers.106

Fig. 2. Contraceptive diaphragms. A. Flat spring. B. Arcing spring. C. Hinged spring (arrows indicate hinges ). (From Speroff L, Darney P: A Clinical Guide for Contraception, Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1992)

Table 5. Types of contraceptive diaphragms

| Diaphragm type | Brand name | Manufacturer | Material | Sizes (mm) |

| Flat spring | Ortho White | Ortho | Rubber | 55–105 |

| Coil spring | Koromex | London International | Latex rubber | 50–95 |

| Ortho Coil Spring | Ortho | Rubber | 50–105 | |

| Omniflex Coil | Milex | Silicone | 60–95 | |

| Arcing spring | All-flex | Ortho | Rubber | 55–95 |

| Koro-flex | London International | Latex rubber | 50–95 | |

| Wide-seal | Milex | Silicone | 60–95 |

Modified from: Allen RE. Diaphragm fitting. Am Fam Physician 2004;69:97-100.

Each type of diaphragm offers its own advantages; however, not all women can be appropriately fitted (Table 6). Satisfactory results are obtainable with any of the varieties, provided a good fit is achieved and the woman uses it consistently. A major benefit of the diaphragm is that it is free of systemic side effects.

Table 6. Indications and contraindications for the contraceptive vaginal diaphragm

| Indications | ||

Female control desired Systemic hormonal contraceptives and IUD contraindicated or unacceptable | ||

Contraindications | ||

| Absolute | Relative | Temporary |

Psychological/mental inability to learn correct use Aversion to touch own genitals Physical inability to master correct use (e.g. marked obesity, fingers too short) Poor pelvic support, with severe cystocele, urethrocele, uterine prolapse History of vaginoplasty, rigid vaginal walls, vaginal malformations, strictures History of recurrent cystitis History of toxic shock syndrome Vaginismus | Need for contraceptive method of greater effectiveness Lack of privacy Moderate cystocele or rectocele or both Dyspareunia Fixed uterine retroflexion Chronic vulvar dermatosis, eczema genitalis, genital psoriasis, contact dermatitis History of cervical dysplasia History of herpes simplex virus infection | Recent delivery (<12 weeks postpartum) Recent episiotomy Acute or subacute vulvovaginitis or cervicitis of any etiology until treated Cystitis, urethritis, or other genital infection until diagnosed and treated |

Modified from: Sobrero AJ, Sciarra JJ. Contraception. In Cohn HF (ed): Current Therapy. Baltimore, WB Saunders Company, 1978.

Diaphragm fitting

Diaphragms are measured by their diameter in steps of 5 mm. They come in sizes from 50–105 mm (Table 5). Extreme sizes are difficult to find; most common are 70–80 mm. Fitting sets generally come with fitting rings, or actual diaphragms, with diameters of 65–85 mm. Using actual diaphragms for fitting instead of fitting rings facilitates the patient's understanding of how the diaphragm works and how it feels when placed in the vagina.

The diaphragm should be selected only after a gynecologic examination and careful assessment of the condition of the pelvic organs. Note the depth and elasticity of the vagina and the tone of vaginal walls and the perineum, as well as the presence or absence of cystocele, rectocele, or urethrocele, and of a recess behind the symphysis pubis. Not infrequently, two women with the same vaginal depth require a different size or type of diaphragm because of marked differences in vaginal wall tone and elasticity. Individual anatomy determines the choice.

One anatomic point of much value in determining the type of diaphragm that can be properly fitted is the condition of the retropubic space. In most women, a well-defined recess is located behind the pubic arch; the anterior part of the diaphragm rim should fit in this space, resting in front against the symphysis. When the anterior vaginal wall is relaxed due to poor vaginal tone or a cystourethrocele, this space is obliterated. In these cases the diaphragm will not fit well and tends to sag. In such cases, the diaphragm cannot be prescribed and another method should be advised.

The proper diaphragm size is the largest one that fits snugly between the posterior vaginal fornix and the retropubic recess without being felt by the patient. If the diaphragm is too small when placed in the posterior fornix, it will not reach the retropubic groove, and if it fits in the retropubic space, it may have been placed onto the cervix without covering it. In both instances, the diaphragm will not form an adequate barrier. When it is too large, it falls anteriorly and causes discomfort, or it may project from the vagina and drop posteriorly, allowing the penis to pass over it during intercourse. In either case, the diaphragm does not provide a barrier, negating its contraceptive value. With correct sizing, only the tip of the index finger tightly fits between the anterior part of the diaphragm rim and the retropubic vaginal mucosa.

Once the appropriate size is found, the patient should be asked to cough or Valsalva to test whether the diaphragm remains in place. The diaphragm forms a partition that divides the genital tract in two sections: the upper including the cervix and the lower serving as the channel for the penis. Inserting the diaphragm with the dome up or down makes no difference as long as it is well fitted. The rubber of the dome wrinkles under the lateral vaginal compression against the ring; this action provides adequate space and elasticity for unimpeded normal coital activity without either partner feeling the device.

In contrast to traditional fitting techniques, several studies have looked at use of a single-size contraceptive diaphragm.107, 108, 109 A multicenter trial of 450 couples found that 98% of women were able to be fitted with the singe-size diaphragm, and that efficacy was similar to the standard diaphragm. The authors suggest that a single-size diaphragm may allow for easier access and provision, eliminating the need for a pelvic exam or formal fitting.110 This non-latex, single-size diaphragm was granted market clearance by the US FDA in 2014, and is now available in over 25 countries worldwide.110

Women requesting the diaphragm should be taught to palpate the cervix and probe the retropubic space where the anterior portion of the diaphragm rim is positioned. Digital palpation of the cervix, how it feels when covered by the rubber, and touching the rim behind the pubic bone are critical steps for her to master. She should be instructed on the important anatomic landmarks and how the diaphragm works. A pelvic model and a diaphragm may be useful for this purpose. Using actual diaphragms during teaching facilitates understanding. The patient learns that the vagina is internally closed and that there is no danger that the device will enter the uterus and be lost in her body, impossible to retrieve. Many women need assurance that the size of the diaphragm has little relation to the amplitude of the vagina.

The patient should be encouraged to practice inserting and removing the diaphragm several times to familiarize herself with the technique. This practice provides confidence about her handling of the device, as well as reassuring the physician about the patient's mastery of the technique. The need for thorough washing of the hands before insertion and removal should be stressed. Consider a follow-up appointment in 1 week, during which the woman should practice insertion and removal at home, leaving it in the vagina overnight or even a full day. Caution should be taken in recommending it for contraception until after proper use is confirmed. Inserting the diaphragm at home might be facilitated by squatting or sitting on a toilet or standing with one foot on a stool or the toilet seat while bending forward. If the diaphragm causes discomfort, it is too large, wrongly inserted, or contraindicated. The success of the method often depends on the care taken to instruct the woman on the proper technique.

Diaphragm use and care

Gels or creams provide lubrication to facilitate insertion of the diaphragm. A lubricant must not contain products damaging to the rubber or irritating to the woman or her partner. Approximately two inches or a spoonful of the spermicidal jelly or cream is placed in the cup of the diaphragm, and some of it is smeared on the rim and the other face of the device. Jellies provide more lubrication. A cream or foam is indicated when less lubrication is desired; foams are less favorable for this purpose. Previously, the adjuvant spermicidal jellies and creams were felt to have potential bactericidal properties and perhaps diminish the risk of acquiring some STIs. While some new promising products are in development,111 current studies have not consistently supported the idea of spermicides for STI protection, and spermicides should not be recommended for use alone for prevention of HIV or other STIs.17

Traditional teaching advocates that the diaphragm and spermicidal agent may be inserted hours before intercourse, but if more than 2 hours elapse, additional spermicide should be placed in the upper vagina for maximal protection from pregnancy. Without any scientific data to support it, removal of the diaphragm is advised after 6–8 hours from ejaculation. The diaphragm may remain in the vagina overnight but not for more than 24 hours. When repeated coitus occurs, a fresh application of the spermicide may be inserted with an applicator or with a finger without removing the diaphragm. A Brazilian study comparing subjects who used a diaphragm without spermicide continuously, with subjects using a diaphragm plus spermicide only at the time of intercourse, demonstrated that the continuous users experienced lower failure rates and were more likely to continue the method.112 However, other studies have suggested higher failure rates when spermicide is not used,17, 113 and thus clear conclusions on the need for adjuvant spermicide cannot be made. For the sexually active woman, insertion of the diaphragm may become part of her daily routine before retiring, because many users prefer to have it in place well in advance of any possible coitus to avoid the need for extemporaneous preparation. To remove the diaphragm, the patient inserts her index finger under the anterior portion of the rim and pulls the device downward and outward.

Diaphragm use during menstruation is typically not recommended, but if it is desired, the diaphragm should not be placed too long before intercourse, and it should be removed shortly afterward. The danger of toxic shock syndrome (TSS) with prolonged retention of the device should be emphasized, because TSS has been described after diaphragm use.114, 115 Although TSS is rare, approximately 95% of cases reported have been temporally related to menstruation.38, 39, 114, 115 Patients should be counseled that prolonged retention and improper fitting can cause vaginal irritation, even mucosal damage.

A major problem in prescribing a diaphragm is the absence of well-trained personnel. Fitting demands skill, patience for teaching, and time (usually 15–20 minutes). Because diaphragms are less popular now than they were historically, adequate supplies (all models and sizes) often are not available in clinics. Another issue is societal in nature; many women are conditioned not to touch or explore their genitals. In some instances, a woman's attitude toward the insertion of tampons may provide insight to her feelings about placing the device in the vagina and ensuring its proper position. Obese women, women with short fingers, and those with manual limitations may not be able to use this method.

If properly maintained, a diaphragm can last several years, making it a cost-effective contraceptive method. After use, the diaphragm should be washed, dried thoroughly, and placed in its container. If desired, it can be powdered with corn starch. However, talcum powder contributes to the rapid deterioration of the rubber. Periodically, the diaphragm should be inspected against a strong light for weak spots or perforations.

Effectiveness

The diaphragm is an effective method of birth control when fit is appropriate and it is used consistently. The degree of effectiveness depends to a large extent appropriate fit and the motivation of the user. Estimates of first-year pregnancy rates in the US with perfect and typical use are 6 and 16%, respectively.19 Failure rates do not differ by parity, compared with the contraceptive sponge or cervical cap.24 One study reported a lower failure rate in women older than 35 years than in younger women. In this study, successful diaphragm users are older and married, have completed their families, are experienced with the diaphragm or other barrier methods, are better educated, and have higher socioeconomic status.116 However, successful use by very young females showed that the method is suitable for all age groups, provided appropriate fit, training, and support are available.24

Insufficient evidence exists to support use of adjuvant spermicidal products to increase the effectiveness of the diaphragm, although the practice is common.17 The spermicide theoretically offers two added contraceptive advantages: spermicidal activity and an additional mechanical obstacle to sperm migration. A superior pregnancy rate of one per 100 woman-years with the continuous use of a 60-mm fit-free arcing diaphragm without spermicide, removing it briefly every day for washing only, was reported.113 A retrospective analysis in Brazil of the same practice found that continuous use carried a lower failure rate than the one found in a group of women using the diaphragm with a spermicide before each act of intercourse.112 It was speculated that the difference was due to the failure of noncontinuous diaphragm users to use the device on every sexual occasion because of the inconvenience of inserting it on demand. In contrast, a prospective British study projected to study 200 volunteers using a fit-free 60 mm diaphragm for 1 year was halted after enrolling 110 women because of a high failure rate—24.1 per 100 woman-years (29.5 for the women without diaphragm experience and 17.9 for women with barrier contraceptive experience). Major reasons for discontinuation, apart from contraceptive failure, were malodor and problems with removal and insertion.113

Diaphragm use is felt to offer protection against sexually transmitted infections, though studies have varied in reported rates of reduction.117, 118 The utility of diaphragms with or without spermicides and lubricants in preventing HIV transmission has been a recent focus of family planning research.111, 119, 120, 121, 122 While many studies have been promising, the role of vaginal microbicides alone or in conjunction with diaphragm use for reduction of HIV and STI transmission is not settled. More research is needed to explore this potentially significant HIV-reduction strategy.123

The diaphragm offers protection from human papilloma virus, as diaphragm users experience fewer changes in cervical cytology and fewer cases of cervical dysplasia, carcinoma in situ, and cervical cancer.35, 36, 37

An increased incidence of urinary tract infection (UTI) occurs in diaphragm users, compared with users of hormonal methods of contraception.124, 125 It was long believed that the pathogenesis was compression of the distal urethra by the rim of the diaphragm, causing stasis, urinary retention, and ultimately infection. Subsequent studies have shown that a change in the vaginal flora occurs during barrier contraceptive use. The normal vaginal environment, rich in Lactobacillus acidophilus, possesses an acidic pH around 4, except during menstruation, infection, and after semen deposition. Spermicides used with the diaphragm, as with other barrier methods, change the natural vaginal microenvironment, replacing it with a flora rich in anaerobes and E. coli, and making a woman more susceptible to bacteriuria.126 A comparison of sexual intercourse alone with sexual intercourse with a diaphragm and spermicide used in the preceding 3 days was strongly associated with increased rates of vaginal colonization with uropathogenic flora, including E. coli, other Gram-negative uropathogens, group D streptococci, and Candida spp. It was concluded that bacterial and fungal vaginal microflora are strongly influenced by the recent use of a diaphragm and spermicide, and minimally affected by sexual intercourse alone.127

CERVICAL CAP

First described by a German gynecologist in the 1830s, the cervical cap was once a commonly used method of barrier contraception in Western Europe. It was similarly popular in the United States in the 1930s until the diaphragm replaced it in popularity. Cervical cap use further decreased with the invention of oral contraceptives in the 1960s.128

Despite its relative lack of popularity in the US, the cervical cap offers effective reversible contraception free of systemic side effects. It likely also offers some degree of protection against sexually transmitted infection.

Types of cervical caps

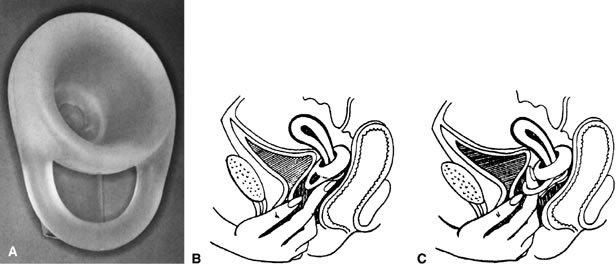

In the 1900s, multiple types of cervical caps were available. Traditional cervical caps included the Prentif or cavity-rim cap, a rubber device with a thick rim; the Dumas or vault cap, a shallow dome-like latex cap; and the Vimule cap, also a dome-like latex cap, thin at the center and thick at the periphery with a slanted rim. All were composed of latex or silicone, and were intended to fit snugly over the cervix (with the Vimule and Duman extending into the vaginal fornices) (Fig. 3). After 2000, two additional products were introduced: the FemCap® (FemCap, Inc., Del Mar, CA), a silicone cap with an indented bowl for covering the cervix and a strap intended to ease removal; the Oves (Veos Ltd., UK), a disposable silastic device with a thin membrane designed to fit over the cervix. As of today, only the FemCap is available in the United States. An additional product, Lea’s Shield (YAMA, Union, NJ), is a silicone bowl-shaped barrier contraceptive device somewhat different in design from the diaphragm and cervical cap that is also available in the United States.

|

Since patient anatomy and factors such as parity will affect the size of cervical cap required, each type of cervical cap is available in a range of sizes, and require personal fitting. Because they are made of rubber, all traditional caps are sensitive to oily and greasy substances. Spermicide is used with traditional cervical caps; for example, the Prentif cap should be filled approximately one-third full with a spermicidal cream before insertion.

The FemCap, FDA approved in 2003, is a unique barrier device composed of highly elastic silicone rubber (Fig. 4), with a shape aptly described as a sailor hat. It consists of a thin dome to fit and cover the cervix completely, a rim extending into the vaginal fornices, and a brim that conforms to the vaginal walls around the cervix. The border of the dome at its junction with the brim forms a slightly narrower and thicker soft, rounded ring to seal the device to the cervix. The one-piece device is provided with a strap of the same material, located over the dome, to facilitate removal. The FemCap comes in three sizes: small (22 mm), for women who have never been pregnant; medium (26 mm), for women who have been pregnant but have not had a vaginal delivery; and large (30 mm), for women who have had a vaginal delivery. Like other cervical caps, spermicide should be placed prior to insertion (approximately ¾ teaspoon total).129

A |

B

Introduced in 2001, Lea's shield is another barrier contraceptive with a design somewhat between a diaphragm and cervical cap (Fig. 5). This intriguing silicone device is unique because a single size may be used by all women. It consists of a thick bowl-shaped dome with an internal diameter of 30 mm to fit and cover the cervix. The rim of the dome is thickest posteriorly, and the opposite side contains a strong, thick loop to facilitate removal. The loop, placed against the anterior vaginal wall, contributes to its fixation and is accessible to the fitting and removal finger. The dome contains a hole at its apex connecting with a tubular valve running parallel to the dome and the loop. This valve permits the escape of air trapped at insertion and the passage of cervical secretions, thus creating better fit over the cervix. According to manufacturer instructions, Lea's shield should be used with approximately 2 teaspoons of spermicidal gel placed prior to insertion. The device, designed to fit all women, is intended to be sold over-the-counter, but currently it requires a prescription in the United States.17, 129

Use of the cervical cap

Conventional cervical caps differ from diaphragms because they are not placed to fit in the vagina but only to shield the cervix. Less elastic than the diaphragm, cervical caps are held in place by suction on the cervix and by the positive abdominal pressure and weight of the abdominal viscera on the vagina. When fitted and placed properly, the cervical cap is somewhat more difficult to place properly and remove than a diaphragm, even when the cap is provided with a removal string. Typical cervical caps are inserted before intercourse and can be worn for up to 48 hours.

Proper use of the cervical cap requires extensive handling of the genitalia, ability to locate the cervix, and manipulation of the device into proper position. In general, cervical caps should not be worn longer than 2 days and not during menstruation. Based on WHO Medical Eligibility Criteria, women who are being treated or initiating treatment for cervical dysplasia or cancer should not use the cervical cap.130 In addition, caution should be exercised in recommending the cap to women with a very short cervix, poor vaginal support, a severely lacerated, inflamed, infected cervix. It is also contraindicated in women with short fingers, a lack of mechanical dexterity, or an aversion to touching their own genitals. Women in the postpartum period or recent second-trimester spontaneous or induced abortion should defer cervical cap use for 6 weeks. Table 7 lists guidelines for the use of cervical caps.

Table 7. Use of the cervical cap

| Insertion |

| Fill approximately one-third of the cap with spermicidal gel, cream, or foam |

| Place the rim of the cap around the cervix until the cervix is completely covered |

| Press gently on the dome of the cap to apply suction and seal the cap |

| Insert the cap any time up to 42 hours prior to intercourse |

| Removal |

| Leave the cervical cap in place for at least 6 hours after the last intercourse, but not for more than 48 hours from the time it was placed |

| Tip the cap rim sideways to break the seal against the cervix, then gently pull the cap downwards and out of the vagina |

Modified from: World Health Organization Department of Reproductive Health and Research (WHO/RHR) and Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health/Center for Communication Programs (CCP), INFO Project. Family Planning: A Global Handbook for Providers. Baltimore and Geneva: CCP and WHO, 2007

In using the FemCap, the spermicide should be placed in the space between the outer aspect of the dome and the brim, and a smaller amount should be smeared on the edge and anterior of the dome. The FemCap requires a smaller amount of spermicide than the Prentif cervical cap. It is theorized that as ejaculation occurs, the brim, in close apposition to the vaginal wall, will direct the ejaculate and motile sperm toward the space surrounding the dome where most of the spermicide is located.131 Because the greater volume of spermicide is not in direct contact with the vaginal epithelium, it theoretically could cause less local irritation. The device does not require additional doses of spermicide before repeated intercourse. Silicone rubber is nonallergenic, and the cap may be washed with any soap or detergent.

The association between cervical cap use and cervical dysplasia has been evaluated. A Cochrane Review reported that the Prentif cap had a higher proportion of class I to class II cervical cytologic conversions after 3 months of use when compared to the diaphragm (odds ratio 2.3). However, the same review reported no differences between Papanicolaou findings of FemCap users and diaphragm users.132

Effectiveness

Efficacy of the cervical cap in preventing pregnancy is dependent on the design. Two prior randomized controlled trials have been performed. The first compared the traditional Prentif cervical cap to diaphragm, finding that over 2 years of use, pregnancy rates were not statistically different.132 However, a 6-month comparative study between FemCap and a conventional diaphragm showed typical use pregnancy probabilities of 13.5% among FemCap users and 7.9% among diaphragm users (adjusted risk of pregnancy of 1.96).132, 133

Concerning non-contraceptive benefits, Prentif cervical cap users had a lower odds ratio of vaginal ulcerations or lacerations compared to diaphragm users (OR 0.3). FemCap users had a lower odds ratio of urinary tract infections compared to diaphragm users (OR 0.6).132

Evaluation of Lea's Shield demonstrated acceptability, safety, and contraceptive efficacy. One study randomized women to Lea's Shield use with and without spermicide. Adjusted pregnancy rates were 5.6 per 100 women in spermicide users, compared with 9.3 per 100 in non-spermicide users, with a trend toward significance (p = 0.086). Unadjusted rates were similar between groups.134

The cervix is recognized as an important site of entry for HIV during intercourse,135 and cervical caps may provide protection against HIV and other STDs. In addition, the newer FemCap and Lea's Shield offer the potential for improved protection.96

VAGINAL CONTRACEPTIVE INSERTS

Vaginal contraceptive inserts, most commonly in the form of films or suppositories, are intended for use either alone or with a barrier contraceptive. Both films and suppositories require adequate time to dissolve within the vagina prior to initiation of intercourse (usually 10–15 minutes).

Available contraceptive inserts in the United States contain N-9 as spermicide, and include brands names such as Encare (contains 100 mg N-9; manufactured by Blairex Laboratories, Columbus, IN). The vaginal contraceptive film (VCF) is also available (contains 70 mg N-9; manufactured by Apothecus Pharmaceutical Corp, Oyster Bay, NY). A randomized trial of VCF versus placebo film concluded that VCF did not offer added protection against HIV, gonorrhea, and chlamydia over condoms alone.136

CONTRACEPTIVE SPONGE

Perhaps the oldest mechanical intravaginal device used for contraception is the vaginal sponge and its variations. Wads of cloth, cotton tufts, sea sponges, powder puffs, and the like have been used throughout history and are still in use all over the world, either alone or in combination with different solutions, presumably spermicides. The sponge combines mechanical and chemical barriers to sperm. The vaginal sponge provides some advantages over the diaphragm and the cervical cap, although not as much contraceptive protection as the diaphragm. It is self-administered and does not require a pelvic examination or fitting; one size fits all. It has no contraindications, except for persons allergic to the sponge material or the spermicide or persons averse to touching their genitals. Available without prescription, the vaginal sponge can be personally procured, inserted, and removed. It can be used as a back-up method for the condom. There is no waiting period after insertion to be effective. It can be inserted hours before a sexual encounter, avoiding a potentially messy interruption of sexual activity, while upholding confidentiality. The user may engage in repeated coitus without the need for additional preparation.137 Sponges may offer protection against some STDs. Sponges are an appealing and effective option under a woman's control that do not require professional intervention.

The disposable Today sponge was introduced to the US market in 1983. It was withdrawn from the market in 1995 due to FDA compliance issues, as the manufacturer chose to discontinue production rather than change design. In 2005, Today (Mayer Laboratories, Berkley, CA) was reintroduced to the market after FDA clearance. The single-use sponge consists of a molded hydrophilic polyurethane soft foam impregnated with 1 gram of N-9. An indentation on one side allows the sponge to fit against the cervix, and the other side contains a ribbon to facilitate removal. The sponge should be wet with tap water and squeezed prior to insertion.17

Offered in Europe and Canada, Protectaid is a polyurethane sponge containing low concentrations of three spermicides: benzalkonium chloride, sodium cholate, and N-9.138, 139 The Protectaid sponge is pre-moistened in the package; it is not necessary to apply water.

A Cochrane review comparing the sponge with the diaphragm found the sponge significantly less effective at preventing pregnancy. In addition, discontinuation rates were higher with the sponge.140 Effectiveness varies between nulliparous and parous women. First-year unintended pregnancy rates for perfect and typical use are 9% and 16%, respectively, in nulliparous users, compared with 20% and 32% in their parous counterparts.2

Some studies have suggested possible protection from gonorrhoea, chlamydia, and trichomonas acquisition in sponge users,141, 142 though data are limited. A study of commercial sex workers in Nairobi found that the sponge with N-9 did not offer protection against HIV infection.143 The sponge contributed to vaginal dryness, and the seroconversion was credited to an increase in vaginal sores that facilitated viral infection. Women in this study had multiple coital episodes with the sponge; the situation may be quite different in other clinical scenarios. Frequent use of N-9 has been linked to vaginal irritation and mucosal abrasions, which were dose-dependent.144 There have been cases of TSS temporally associated with use of the contraceptive sponge. The risk was mostly related to its use during menstruation and the puerperium and prolonged retention of the device.145

SPERMICIDES

Substances for vaginal application formulated to prevent conception have been in use since pharaonic times and form part of the folklore of most cultures. From the time of their discovery, spermatozoa were found to be killed by many substances. Formal experimentation with chemical inhibiters of sperm began in the 1800s.146 By the 1950s, different vaginal creams, pastes, suppositories, and other vaginal inserts of uncertain quality, suspicious origin, and questionable effectiveness were being marketed. However, with time, these chemical contraceptives became more regulated, with requirements for their safety and effectiveness.

Globally, due the extent of the HIV epidemic, much research focuses on vaginally administered agents protective against STD transmission. Increasing knowledge of the ecology of the human vagina provides basic knowledge related to the problems encountered in the general use of existing spermicides. Considerable research effort is being made by the private and public sector with the goal of finding products with strong bactericidal and viricidal activity, in addition to spermicidal activity, that will not affect the vaginal and cervical epithelia and will preserve vaginal mucosa integrity. Numerous products are at different stages of testing. The pharmaceutical industry seems at times to have remained uninterested in this quest since the market for preparations of this kind will be mostly for populations with meager acquisitive power.

Spermicides are agents that kill spermatozoa or render them incapable or normal function. Microbicides are self-administered prophylactic agents used to prevent transmission of sexually transmitted pathogens, with HIV being the most significant today. In the broadest terms, microbicides may be given through any route or mode of administration, but most current research centers on vaginally-administered, female-controlled products. Given these definitions, there is a basis for overlap between spermicidal and microbicidal agents. The most widely used spermicides—such as N-9, octoxynol-9, and menfegol—are surfactant agents, which disrupt cell membranes and kill bacteria, parasites, and most viruses in vitro.147 Other common compounds have shown spermicidal activity (e.g. benzalkonium chloride, chlorhexidine, gramicidin, cholate, and betadine).

Types of spermicides

An ample array of pharmaceutical methods have been and are still used to deliver spermicides into the vagina. There are traditional forms, such as vaginal jellies and creams, suppositories, and effervescent tablets, with many improvements since their inception. There are newer forms, such as foams, and more recently, the vaginal contraceptive film (Table 8).

Table 8. Brand name spermicide products available in the United States

| Gels, jellies, and creams |

| Advantage 24 Gel |

| Conceptrol Gel |

| Gynol II Extra Strength Jelly |

| KY Plus Jelly |

| Ramses Crystal Clear Gel |

| Shur-Seal Gel |

| Film |

| Vaginal Contraceptive Film |

| Foams |

| Delfen Foam |

| Emko |

| Suppositories/Inserts |

| Encare |

Modified from: Spermicides (Vaginal Route). Available from:

http://www.mayoclinic.org/drugs-supplements/spermicide-vaginal-route/description/drg-20070769 Accessed Jan 2016

Use of spermicide products