Uterine Sarcoma: Histology, Classification, and Prognosis

Authors

INTRODUCTION

Uterine sarcomas represent a small percentage of all gynecologic malignancies. Their incidence reportedly varies between 2.6% and 9.7% of all uterine corpus malignancies and accounts for 1% of all genital malignancies.1,2,3 Although infrequent, uterine sarcomas are among the most lethal of all uterine malignancies. The 5-year survival rate reportedly ranges from 30% to 68%. Because of confusion concerning nomenclature and diagnostic criteria, the reports and results from sarcoma studies are difficult to interpret.

PATHOGENESIS

The multiple tissues composing some of these malignancies have made their pathogenesis speculative. Several etiologic theories have been proposed.4,5,6 Leiomyosarcomas originate from smooth muscle, and endometrial stromal sarcomas originate from endometrial stroma tissue. The confusion concerns those sarcomas containing tissues foreign to the uterus. It is difficult to explain how cartilage, bone, fat, or skeletal muscle suddenly appears in a mature organ where the tissue does not normally reside.

CLASSIFICATION

The literature has been confusing since Virchow's description of “medullary sarcomas” in 1860.7 One reason for this confusion has been the lack of a standardized nomenclature. There have been as many as 119 different terms used for one variety of sarcoma.8 Poor nomenclature exists because of the lack of a generally recognized and accepted classification system. Zenker, in 1864, first suggested the concept of homologous and heterologous elements.9 This is the basis of the classification used today by most authors; however, its adoption has been slow. Homologous refers to tissue normally found in the uterus, such as smooth muscle, endometrial stroma, and vascular and fibrous tissue. Heterologous refers to tissue foreign to the uterus, such as cartilage, bone, skeletal muscle, and fat.

Since Zenker's report, other classifications have been proposed by Ober,5 Bartsich and colleagues,10 and Aaro and associates.11 Ober's classification was the most comprehensive. He adopted Zenker's histologic recommendations and proposed an inclusive histologic classification for uterine sarcomas. His classification separates sarcomas according to the number and type of recognizable sarcomatous and carcinomatous tissues present. Ober further divided his histologic classification into pure and mixed sarcomas. A practical modification of Ober's classification of uterine sarcomas proposed by Kempson and Bari12 follows.

- Pure Sarcomas

- Pure homologous

- Leiomyosarcoma

- Stromal sarcoma

- Endolymphatic stromal myosis

- Angiosarcoma

- Fibrosarcoma

- Leiomyosarcoma

- Pure heterologous

- Rhabdomyosarcoma (including sarcoma botryoides)

- Chondrosarcoma

- Osteosarcoma

- Liposarcoma

- Rhabdomyosarcoma (including sarcoma botryoides)

- Pure homologous

- Mixed Sarcomas

- Mixed homologous

- Mixed heterologous (including mixed heterologous sarcomas with or without homologous elements)

- Mixed homologous

- Mixed Malignant Müllerian Tumors (Mixed Mesodermal Tumors)

- Mixed malignant müllerian tumor, homologous type (carcinoma plus leiomyosarcoma, stromal sarcoma, or fibrosarcoma, or mixtures of these sarcomas)

- Mixed malignant müllerian tumor, heterologous type

- Mixed malignant müllerian tumor, homologous type (carcinoma plus leiomyosarcoma, stromal sarcoma, or fibrosarcoma, or mixtures of these sarcomas)

- Sarcoma, Unclassified

- Malignant Lymphoma

A modification of this classification has been suggested by Clement and Scully.13 Stromal sarcoma and endolymphatic stromal myosis have been combined into one category, endometrial stromal sarcoma. This is subdivided into low grade (endolymphatic stromal myosis) and high grade (endometrial stromal sarcoma).

Endolymphatic stromal myosis was benign in this series but has been classified as a sarcoma because of reported recurrences and metastases.

Pure sarcomas are those malignancies containing a single sarcomatous element, and mixed sarcomas are those containing two or more sarcomatous elements. The sarcomatous elements may be either homologous or heterologous. Pure or mixed sarcomas may be present with or without epithelial malignancies. When epithelial elements (carcinoma) are present, the tumor is called a mixed malignant müllerian sarcoma. The carcinomatous tissue may be either adenocarcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma. This combination of sarcomatous and carcinomatous tissue has caused the greatest confusion in the literature.

Some sarcomas are composed of extremely undifferentiated cells, and it is impossible to adequately identify them histologically. These tumors are categorized as “unclassified.”

PURE HOMOLOGOUS SARCOMAS

Leiomyosarcomas

OCCURRENCE.

Leiomyosarcoma is the most common uterine sarcoma, representing 16% to 75% of all uterine sarcomas.5,10,11,14 Because uterine leiomyomas are so common, many researchers have attempted to establish that leiomyosarcomas result from sarcomatous changes in preexisting leiomyomas. A review of the literature reveals the frequency of this sarcomatous change to vary from 0.13% to 10% of leiomyomas, averaging 1.46%.3,14,15,16,17,18 The actual incidence is much less than this because it is impossible to identify all uterine leiomyomas and to adequately sample all leiomyomas for sarcomatous changes.

CLINICAL FINDINGS.

Because the average age of these patients is the middle 50s, leiomyosarcomas are primarily a disease of postmenopausal women.19,20,21 The majority of these patients will present with abnormal uterine bleeding. This bleeding is postmenopausal in 48% of women with leiomyosarcomas.19 Other symptoms and findings include vaginal discharge, pelvic pain, abdominal or pelvic masses, and vaginal prolapse. The majority of patients do not have the triad of diabetes, hypertension, and obesity.

Norris and Taylor suggested an etiologic relation between pelvic irradiation and uterine sarcomas. However, none of their patients with leiomyosarcomas had antecedent pelvic irradiation.22 In a report from the University of Iowa that included 24 leiomyosarcomas, only two patients had received prior pelvic irradiation: one for benign disease and one for ovarian carcinoma.19

PATHOLOGY.

Gross.

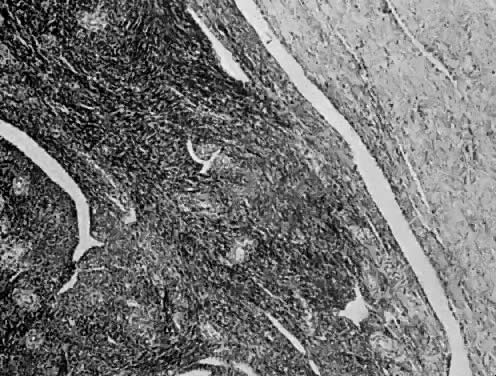

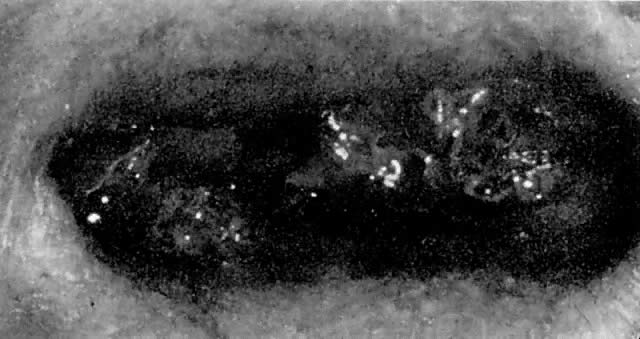

The uterus is frequently enlarged and may be regularly or irregularly shaped, and a mass may be visible through the external cervical os. The size of these tumors varies considerably and ranges from 4 to 40 cm.20 They may have a benign gross appearance and be mistaken for leiomyomas. Because of extensive growth, other tumors may have undergone necrosis and the malignancy is suspected. These tumors have been described as “unencapsulated, soft, gray-white to gray-tan, and bulging on sectioning” (Fig. 1). The whorled pattern of muscle fibers characteristic of leiomyomas is usually not visible.

|

Microscopic.

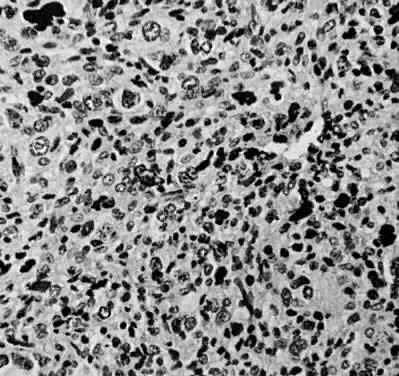

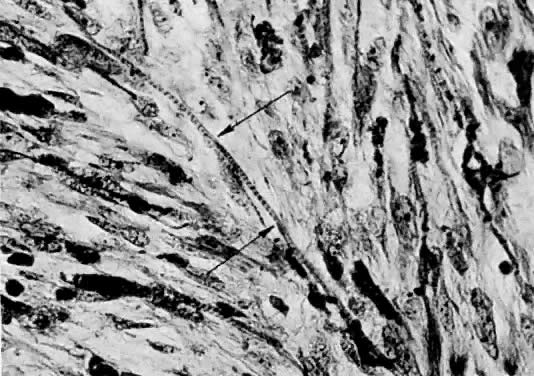

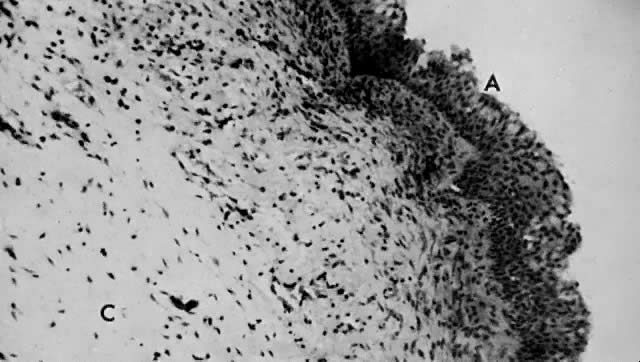

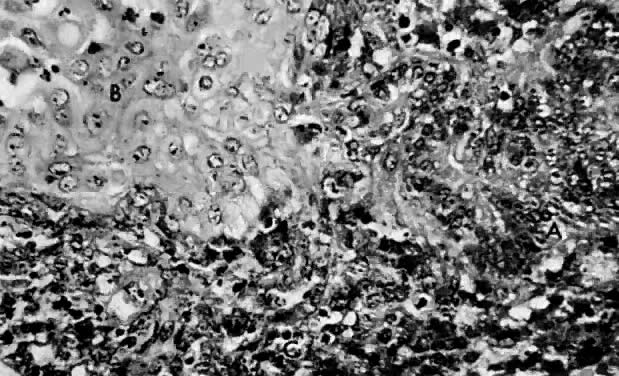

Leiomyosarcomas are composed of malignant uterine smooth-muscle cells. The cells are elongated with tapered ends. Microscopically these tumors may histologically resemble the normal uterine musculature (Fig. 2). The less differentiated the sarcoma, the less it resembles a leiomyoma. As the cellularity increases, nuclear atypism increases, the cytoplasm becomes more eosinophilic, and the number of giant cells increases (Fig. 3).

|

The microscopic diagnosis of leiomyosarcomas and other sarcomas has evolved slowly. Many authors have related the number of mitotic figures and the diagnosis of sarcomas.11,12,16,21,23,24 Evans was the first to document this information in 1920. He divided his cases into high, moderate, and low mitotic counts, depending on the number of mitotic figures per cubic millimeter of tissue.16 Novak and Anderson3 in 1937, Kimbrough2 in 1934, and Randall15 in 1943 reported supporting evidence. Several other diagnostic criteria have been suggested including cellularity, pleomorphism, evidence of giant cells, anaplasia, and evidence of blood vessel invasion.3,15,25 Most authors now accept 10 mitotic figures per 10 high-powered fields (HPF) as diagnostic of sarcomas. In 1981, Ellis and Whitehead discussed some of the possible flaws in this method. They stated that because of the difference in microscopes, the area of a HPF could differ by a factor of six. They suggested that for this reason the number of mitoses be expressed as the number of mitoses per square millimeter.26 Despite this admonition, most researchers agree that the mitotic count is the most reproducible and prognostically accurate method for diagnosing homologous sarcomas.27

Physicians should count the number of mitotic figures in at least 20 HPF from various areas of the tumor. The average number of these mitotic figures determines the malignant potential of the tumor. Kempson and Bari12 have demonstrated that there is nothing magical about the number 10. In their study, the patients with five to nine mitotic figures in 10 HPF did poorly. The mitotic figures can be very difficult to identify; therefore, the number counted can only be an approximation. Most researchers agree if the average number of mitotic figures per 10 HPF is 10 or greater, the tumors are definitely sarcomas.20

Atypism of the stromal cell and the presence and number of giant cells are not directly related to the diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma. However, the more undifferentiated the sarcoma, the more atypical the cells. Tumors with large numbers of mitotic figures contain more giant cells and more atypical stromal cells. Vascular invasion is an infrequent finding and is usually observed in leiomyosarcomas with more than 10 mitotic figures per 10 HPF.

PROGNOSIS.

A number of factors influencing survival have been studied:

Anaplasia28

Race18,25

Cellularity11

Pleomorphism3,11,17,18,29

Presence of giant cells12,28

Presence of mitotic figures12,20,25

Evidence of blood vessel invasion10,14,18

Amount of disease25,29,30

Menarche status14,25

Origin in leiomyomas3,17,18,28,29

Gross appearance of disease25,29

Once a sarcoma has been diagnosed, survival is directly related to the volume of tumor. The amount of disease rather than the method of therapy seems to be the most important factor affecting survival. The survival is best if the disease is confined to the uterus, and it decreases as the extent of the disease increases. The 5-year survival rate for leiomyosarcomas has been reported to vary from 0 to 68%.10,14,17,19,25,28

Spiro29 reported 77% of his patients had recurrent disease within 24 months; 88.2% of our patients had recurrences within 24 months.19 Within 24 months, 94.1% of our patients with recurrent disease died. The most common sites of recurrence are the pelvis and lungs; other sites include the liver, skin, spinal cord, ribs, and skull.19

STROMAL TUMORS

In general, the literature concerning sarcomas is confusing, especially endometrial stromal sarcomas and endolymphatic stromal myosis. This confusion is demonstrated by the variety of terms in the literature, including endometrial stromal endometriosis, endolymphatic stromal myosis, endometrioma interstitiale, endometrial stromal sarcoma, and stromatosis.31,32,33,34 Confusion surrounds the origin of these cells, their relation to vascular sarcomas, and the criteria for malignancy.

These are the second most common pure homologous sarcomas. They reportedly account for 12.5% to 23% of uterine sarcomas.1,12,19 Gitstein and colleagues reported that of the approximately 400 cases reported in Israel, more than half are high grade.35

Stromal Sarcoma (High Grade)

CLINICAL FINDINGS.

This sarcoma is common in postmenopausal women; the ages range from the second to the eighth decade of life.

These patients usually present with abnormal uterine bleeding, commonly postmenopausal. Other reported symptoms include abdominal enlargement and pelvic discomfort. There are no medical diseases common to patients with stromal sarcoma, and none of the eight patients seen at the University of Iowa received prior pelvic irradiation.19

PATHOLOGY.

Gross.

The uterus is frequently enlarged and irregular. These tumors are soft and grayish to yellow and have bulging margins. They have infiltrating borders and frequently involve not only the endometrium but also penetrate the myometrium. Hemorrhage and necrosis are common as they increase in size and occupy more of the uterine cavity.

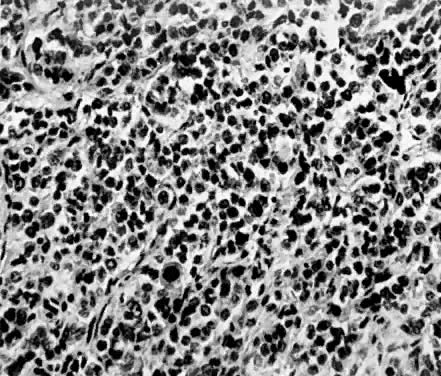

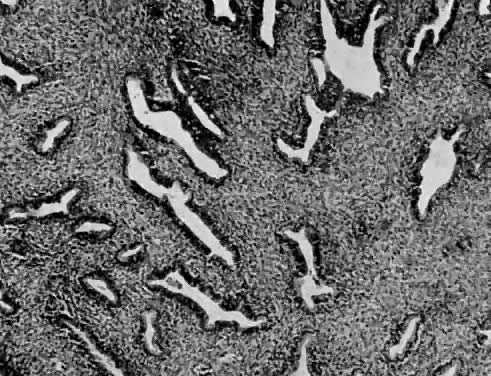

Microscopic.

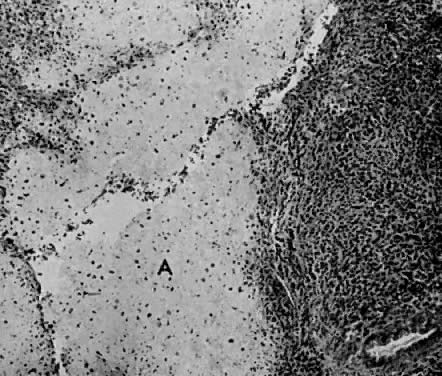

Endometrial stromal sarcomas are composed of monotonous sheets of cells with basophilic nuclei and scant cytoplasm. These cells are usually round with dark-staining nuclei and resemble cells of the endometrial stroma as opposed to the long, thin, tapered cells of the uterine musculature21 (Fig. 4). Endometrial glands may or may not be present, and their absence may be the result of either an atrophic endometrium or replacement by the stromal sarcoma. The endometrial stromal sarcoma may invade the myometrial smooth muscle to various degrees (Fig. 5).

|

Certain researchers have suggested a possible histologic relationship between endometrial stromal sarcoma and hemangiopericytomas.36,37 Electron microscopic studies have demonstrated a resemblance between stromal sarcoma cells and proliferative endometrium but no resemblance to the pericytes of hemangiopericytomas.38 Vascular involvement is observed less frequently in high-grade than low-grade tumors. Spread by high-grade tumors is primarily by hematogenous means to the lungs and bone and transperitoneally to the abdominal organs.39

DIAGNOSIS.

The diagnosis of a high-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma is based on a mitotic count of 10 or more mitotic figures per 10 HPF.

PROGNOSIS.

The prognosis depends on the amount of disease. The reported 5-year survival ranges from 0 to 70%. This wide range results from confusion about the diagnosis.12,19,32,39 When reports of similar histologic types are compared, the reported 5-year survivals are 0, 25%, and 55%.12,19,39

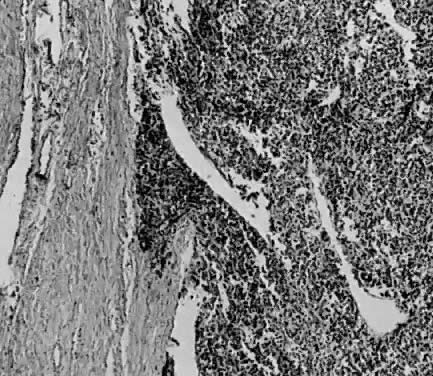

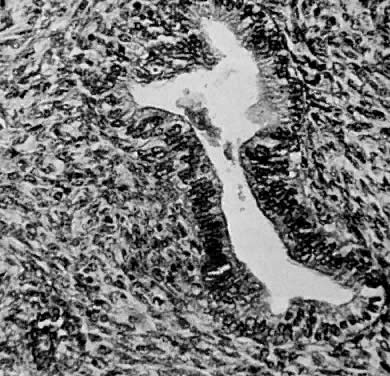

Endolymphatic Stromal Myosis

Numerous authors have reported that endometrial stromal myosis occurs predominately in premenopausal women.39,40,41 Bard and Zuna reported an average age of 42 years.40 Endolymphatic stromal myosis is composed of nodules of stromal cells with rounded nuclei and dense cytoplasm (Fig. 6). These tumors have frequently been confused with endometrial stromal sarcoma. The determination of the number of mitotic figures per 10 HPF is important in separating these two tumors. Endolymphatic stromal myoses have fewer than five mitotic figures per 10 HPF, and they have pushing rather than infiltrating margins (Fig. 7). Although these tumors have an innocuous appearance and prolonged clinical course, they can be fatal. The 5-year survival reportedly ranges from 66% to 100%.19,34,40 Some of these tumors reportedly contain estrogen and progesterone receptors.41,42 This may be the reason why some of them are sensitive to progesterone therapy. Bard and Zuna reported that nearly 40% of their Stage 1 endometrial stromal myosis (low grade) eventually recurs in the pelvis, abdominal cavity, and lungs. These recurrences may manifest themselves years after primary therapy.39,43,44

|

Endometrial stromal myosis frequently has apparent extensive vascular invasion. In spite of this apparent invasion, this tumor has an excellent prognosis. Fung and associates studied this apparent paradox by using electron microscopy, immunoperoxidase identification of Factor VII as a marker for the endothelium, and light microscopy for serial sections. The spaces were demonstrated to be vascular. They reported that the tumor cells had indented and invaginated the endothelium, creating an illusion that the tumor was present within the lumen. In reality, an intact endothelium and basement membrane separated the tumor from the lumen.45

Piver and colleagues reported that some survival may be due to the hormonal sensitivity of these tumors.42

Vascular Sarcomas

Tumors of vascular origin such as hemangiopericytomas are extremely rare, and readers are referred to the report by Pedowitz and colleagues37 for further information concerning these tumors.

Müllerian Adenosarcoma

OCCURRENCE.

This is a newly identified variety of uterine sarcoma, and only 14 cases have been reported. Clement and Scully46 first described 10 cases in 1974. Roth and associates47 reported the electron microscopic findings in one additional patient. Blythe and co-workers,19 in a 33-year review from the University of Iowa, added three cases.

CLINICAL FINDINGS.

The ages of patients reported by Clement and Scully46 ranged from 21 to 84 years, averaging 71 years. The ages of the three patients from the University of Iowa averaged 62 years. The gravidity of all reported patients ranged from 0 to 16. The majority of all patients presented with abnormal uterine bleeding. Other presenting symptoms included abdominal pain and vaginal discharge. None of the patients in the three reports had received prior pelvic irradiation.

PATHOLOGY.

Gross.

The uterus is frequently enlarged, and the tumors may be large and fill the uterine cavity. Although Clement and Scully46 reported four cases in which the tumor occluded the endocervical canal, in only one instance did it prolapse through the external cervical os. None of the patients in the University of Iowa study had a mass prolapsing through the external cervical os. Clement and Scully described their tumors as soft and ranging in color from gray to white and pink to yellow.

Microscopic.

This polypoid tumor displays a distinct pattern composed of benign-appearing endometrial glands surrounded by malignant stromal cells. The glands are uniformly distributed throughout the stroma, resemble proliferative endometrium, and are lined by a layer of columnar epithelium. Some of the branching glands show focal cellular stratification with nuclear pleomorphism. In addition, some glands contain hyaline secretions that stain by the periodic acid-Schiff technique. The glands are surrounded by a dense cellular stroma.

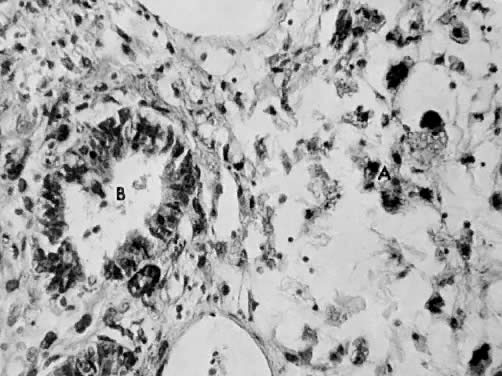

The stromal cells have oval or round nuclei and prominent nucleoli surrounded by scant eosinophilic cytoplasm. They frequently have indistinct cell borders. The stroma may vary from dense periglandular cellularity to areas of sparse cellularity. Several mitotic figures may be visible, and the reported numbers vary between 7 and 16 per 10 HPF. Focal areas of hemorrhage and necrosis are present (Fig. 8 and Fig. 9).

|

Electron microscopic studies support the theory that these malignancies arise from undifferentiated multipotential müllerian stem cells.4,5,6,7

PROGNOSIS.

These tumors are classified separately, not only because of their distinct microscopic pattern but also because they reportedly are less lethal. Five of Clement and Scully's46 patients were living and well at 3 months, 1 year, 2½ years, 6 years, and 7½ years; one patient died at 4 years, clinically free of disease. Four patients had recurrent disease: three were local recurrences, and one was distant. The three patients reported from the University of Iowa had surgical removal of their disease. Patients died at 36 months and at 8½ and 10½ years with no evidence of disease. The activity of these three tumors supports Clement and Scully's46 original contention that these tumors are less malignant and should be classified accordingly.

PURE HETEROLOGOUS SARCOMAS

Rhabdomyosarcoma

Rhabdomyosarcoma is the most common pure heterologous sarcoma. Other heterologous sarcomas include chondrosarcoma, osteogenic sarcoma, and liposarcoma, which are curiosities in their pure form and will not be discussed further.48

OCCURRENCE.

Rhabdomyosarcomas occur in two locations in the female genitalia. Some are confined to the uterine cavity (myometrium), and others arise from the cervix and vagina. Vaginal rhabdomyosarcomas of young girls are commonly referred to as sarcoma botryoides.49

Anderson and Edmansson reported the first rhabdomyosarcoma of the corpus uteri in 1869, and the first English report was by Robertson in 1909.50,51 Donkers and colleagues52 in 1972 reported two cases and reviewed the literature. They were able to find 49 rhabdomyosarcomas of the corpus uteri reported since 1869. Except for reports by Kukla and Douglas51 and Middlebrook and Tennant,50 most studies are reports of one to three patients. A 33-year review of all uterine sarcomas at the University of Iowa revealed no pure corpus uteri rhabdomyosarcomas.

CLINICAL FINDINGS.

The ages of the 49 patients first reported and the 2 patients reported by Donkers and colleagues ranged from 36 to 90 years. Forty-seven of 51 patients were 50 years of age or older. Postmenopausal uterine bleeding was the most common presenting symptom in these 51 patients.52

PATHOLOGY.

Gross.

The uterus is frequently enlarged. The tumor has been described as polypoid or pedunculated; its consistency is soft and fleshy, and necrosis can be present. The color varies widely, from brown to pink and white to yellow.51

Microscopic.

In 1946, Stout53 established the histologic features of skeletal muscle tumors. In 1950, Stobe and Dargeon54 classified some of these tumors as “embryonal” rhabdomyosarcomas. In 1956, Riopelle and Theriault55 described a distinct histologic pattern as “alveolar” rhabdomyosarcoma. A third histologic variety is “pleomorphic.” A uterine rhabdomyosarcoma may contain one, all, or any combination of these forms.

The pleomorphic form is usually very cellular, and the cells are characteristically spindle shaped. The pleomorphic cells have also been described as broad, elongated, straplike or ribbon-shaped cells.56 Multiple nuclei may be arranged in tandem or syncytium-like masses. Longitudinal striations and cross-striations may be demonstrated.

Alveolar rhabdomyosarcomas are characterized by “alveoli” separated by delicate trabeculae formed by neoplastic muscle fibers. This histologic pattern resembles epithelial adenocarcinomas. The center of each alveolus may contain unattached cells, which may be giant or multinucleated. The giant cells may have longitudinal or cross-striations.

Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma is characterized by long, thin, tapering cells. There is a single central nucleus with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. Some cells may be round with scant cytoplasm and no distinguishing features. Longitudinal striations may be difficult to see, but distinct cross-striations may be very numerous and easy to identify56 (Fig. 10).

|

PROGNOSIS.

There have been few reported pure uterine corpus rhabdomyosarcomas. One must refer to literary reviews to learn the survival rates. Kukla and Douglas51 stated that 14 of 19 patients died between 1 day and 11 months after therapy. Five patients were alive and well 7 to 36 months after therapy. Rachmaninoff and Climie57 reported five patients who died at 6 to 33 months and two patients who were alive and well at 5 years. Wolfe and Mackles58 reported one patient who died at 6 months. Peckham and Green59 reported one patient who died at 8 months. A long survival with a uterine corpus rhabdomyosarcoma seems unlikely.

Sarcoma Botryoides

OCCURRENCE.

Sarcoma botryoides is the most common tumor of the genitourinary tract in infants and children and the most common sarcoma of somatic soft tissue in children.60 In females, this is a rare rhabdomyosarcoma arising from the vagina and cervix of young girls.

CLINICAL FINDINGS.

Sarcoma botryoides is primarily a vaginal tumor of small girls. Hilgers and colleagues61 and Davos and Abel162 cumulatively reported on 66 patients. The patients' ages ranged from 5 months to 5 years. Sarcoma botryoides usually presents as an asymptomatic mass and may first be observed by the parents when bathing the child. Blood or a mucous discharge may appear on the child's diapers or underwear. In Hilger and colleagues' report on 61 patients with sarcoma botryoides, 44.3% had a vaginal mass, 21.3% had vaginal bleeding, and 16.4% had both symptoms.61 Symptoms arising from areas other than the urogenital system are usually secondary to metastatic disease.

PATHOLOGY.

Gross.

In 1854, Guersant first reported a polypoid tumor of the vagina in a young girl.63 Pfannensteil64 in 1892 first described the grapelike appearance of this tumor. The term sarcoma botryoides (grapelike) is descriptive, based on the gross appearance of the tumor.

Grossly, these tumors are composed of multiple polyp-like structures in a botryoides growth pattern. They appear as a mass of edematous polyps. The surface is shiny and whitish pink to grayish red. The polyps frequently fill and extrude from the vagina (Fig. 11). The anatomical location provides the tumors with a space to grow and accounts for the grapelike appearance of the tumor. When sectioned, the tumors appear translucent with an edematous or myxomatous cut surface and resemble a benign inflammatory polyp.

|

Microscopic.

In 1900, Wilms described the microscopic details of this tumor.6 Sarcoma botryoides is usually an embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma but may contain any or all three histologic types (alveolar, pleomorphic, or embryonal). The following microscopic features are characteristic: an overlying epithelium, a subepithelial cambium layer, round and spindle-shaped cells, and central myxomatous stroma.61

These tumors originate in the subepithelial tissue of the vagina. As they grow into the vaginal cavity, the polyps retain the original vaginal squamous epithelial covering (Fig. 12).

Immediately beneath the covering epithelium is the cambium layer. This layer is composed of round and spindle-shaped cells closely packed together. The typical rhabdomyoblast may be visible here. The rhabdomyoblast is an immature malignant cell that resembles striated muscle cells in different phases of development: round, racket, or straplike forms.61,65,66 The cytoplasm is eosinophilic and granular. Cross-striations can be readily demonstrated with the use of a phosphotungstic acid-hematoxylin stain (PTAH).

The central portion of the polyps is relatively acellular (see Fig. 12) and is composed mainly of myxomatous tissue, but a few spindle- or stellate-shaped cells may be visible.

Transmission electron microscopy of these tumors is of little diagnostic value. Toker has stated that determination of “characteristics of the neoplasm (rhabdomyosarcoma) on an ultrastructure basis has not been possible.”67 The rhabdomyoblasts with their cross-striations are best identified with light microscopy (see Fig. 10).

PROGNOSIS.

The prognosis for this tumor is poor. The 5-year survival reportedly varies from 0 to 50%.49,60,61,68,69 Hilgers and colleagues61 reported that the following factors appear to favor the prognosis: minimal delay between the onset of symptoms and operation, superficial involvement in the vagina without local extension, anterior located lesions, adequate aggressive surgical resection, and total vulvectomy as part of the surgical procedure.

MIXED SARCOMAS

Sarcomas may be any combination of homologous or heterologous elements. Combinations of homologous forms result in mixed homologous sarcomas and combinations of heterologous forms in mixed heterologous sarcomas. In either case, these tumors are purely homologous or heterologous although the tumor may consist of more than one sarcoma. If one, two, or more heterologous elements are present and homologous forms are also present, the tumor is still a mixed heterologous sarcoma. These are unusual sarcomas. In a 33-year review at the University of Iowa, one patient had a mixed heterologous sarcoma composed of a rhabdomyosarcoma and an osteosarcoma.

Mixed Malignant Müllerian Sarcomas

OCCURRENCE.

In a series reported by Chuang and colleagues,70 mixed malignant müllerian sarcomas represented 2% of all uterine malignancies. These tumors reportedly accounted for 20% to 42% of all uterine sarcomas.1,11,19,70,71,72 The homologous variety accounts for 25% to 60% and the heterologous variety for 6% to 58% of these tumors.19,70,73 Most authors report the homologous variety to be the most common. These tumors are divided into subgroups depending on their histologic components. Because these different components are mainly of histologic rather than prognostic interest, these tumors will be discussed as one group (mixed malignant müllerian sarcomas) except when indicated.

CLINICAL FINDINGS.

These uterine sarcomas, like most uterine malignancies, occur mainly in postmenopausal women. Sternberg and colleagues74 reported an average age of 59.1 years; Rachmaninoff and Climie57, 64 years; DiSaia and associates,30 59.9 years; Williamson and Christopherson,73 64 years; and Blythe and co-workers,19 63.5 years. This is a slightly older age of incidence than that for the previously discussed sarcomas. All of these authors report abnormal uterine bleeding as the most common presenting symptom.

Parity reportedly varies in these patients from zero to more than four.19,67,74,75 The incidence of obesity, diabetes, and hypertension in mixed müllerian sarcomas is shown in Table 1. Schwartz and colleagues76 reported 104 cases of various sarcomas including mixed malignant müllerian sarcomas. They could demonstrate no correlation between these tumors and diabetes, hypertension, and obesity. Table 2 lists the race of these patients. Pelvic irradiation has been of interest to students of uterine sarcomas, and Table 3 lists the percentage of patients who had received prior pelvic irradiation regardless of the reason. Schaepmen-Van Geuns reported that previous irradiation was not an important etiologic factor in these tumors.79

TABLE 1. Incidence of Obesity, Diabetes, and Hypertension in Mixed Malignant Müllerian Sarcomas

| Obesity | Diabetes | Hypertension |

Author | (%) | (%) | (%) |

Norris et al72 | 32.0 | 3.2 | 45.0 |

Rachmaninoff and Climie57 | 30.0 | 3.3 | 36.7 |

Williamson and Christopherson73 | 41.7 | 10.4 | 31.3 |

DiSaia et al30 | 45.0 | 40.0 | 24.0 |

Blythe et al19 | 55.6 | 5.6 | 50.0 |

Peters et al65 | - | 17.0 | 33.0 |

TABLE 2. Mixed Malignant Müllerian Sarcomas by Race

Authors | White (%) | Black (%) | Other (%) |

Sternberg et al74* |

| 80.9 |

|

Ober and Tovell71 | 76.0 | 24.0 | 0 |

Edwards et al75 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

Norris et al72 | 76.0 | 24.0 | 0 |

Rachmaninoff and Climie57 | 60.0 | 30.0 | 10.0 |

DiSaia et al30 | 70.0 | 30.0 | 0 |

Peters et al65 | 86.5 | 12.5 | 0 |

* Report from Charity Hospital: Ratio of black to white hospital admissions is normally 2:1. Data for white and other not given

TABLE 3. Mixed Malignant Müllerian Sarcomas in Patients With Previous Pelvic Irradiation

| Patients | |

Author | No. | % |

Sternberg et al74 | 0/21 | 0 |

Carter and McDonald77 | 0/6 | 0 |

Edwards et al75 | 2/7 | 28.6 |

Norris et al72 | 13/60 | 21.7 |

Rachmaninoff and Climie57 | 2/30 | 6.7 |

Masterson and Kremper78 | 5/25 | 20.0 |

Chaung et al70 | 8/49 | 16.0 |

Williamson and Christopherson73 | 6/48 | 12.5 |

DiSaia et al30 | 0/94 | 0 |

Blythe et al19 | 8/22 | 36.4 |

Peters et al65 | 23/79 | 49.5 |

PATHOLOGY.

Gross.

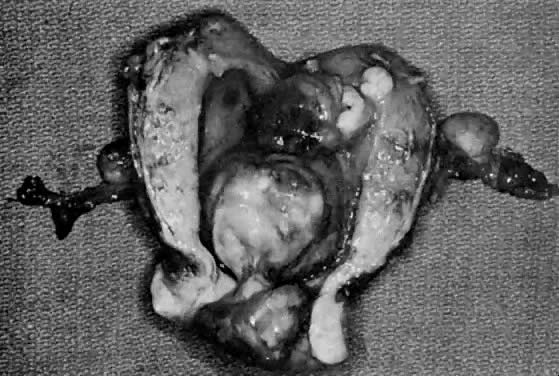

The uterus has been described as enlarged in the majority of patients.19,57,70,72,77,78 In the reports that separated mixed homologous and heterologous tumors, both varieties had enlarged uteri.19,71 These tumors grow from a broad base in a polypoid fashion to occupy most of the uterine cavity. They are usually soft, friable tumors and are reddish pink, yellow to gray and red, or pink, with areas of necrosis and hemorrhage.72,75 These tumors are frequently confused with prolapsing leiomyomas because a mass may be seen protruding through the external cervical os (Fig. 13) (Table 4).

TABLE 4. Incidence of Prolapsing Cervical Mass in Mixed Malignant Müllerian Sarcomas

| Patients | |

Author | No. | % |

Sternberg et al74 | 12/21 | 57.1 |

Carter and McDonald77 | 2/6 | 33.3 |

Rachmaninoff and Climie57 | 6/30 | 20.0 |

Masterson and Kremper78 | 10/25 | 40.0 |

Williamson and Christopherson73 | 16/48 | 33.3 |

Blythe et al19 | 5/18 | 27.7 |

|

Microscopic.

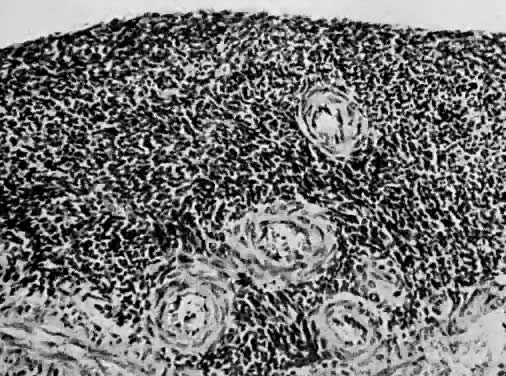

Various terms including mixed mesodermal tumors, mixed müllerian mesenchymal sarcoma and carcinoma, and mesenchymal sarcomas have been used to describe these tumors.5,57,70,70,71,72,73,74,80 These sarcomas contain both stromal and epithelial malignancies and may contain a variety of either malignancy.

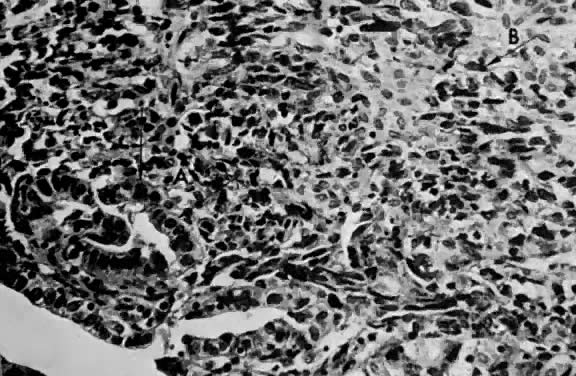

The homologous variety contains sarcomatous elements derived from tissue normally present in the uterus. These tumors are commonly referred to as carcinosarcomas (Fig. 14 and Fig. 15).

|

|

The heterologous variety contains sarcomatous elements derived from tissue foreign to the uterus. These tumors are commonly referred to as mixed mesodermal tumors. The name should include the term heterologous because this is specific (Fig. 16, Fig. 17, and Fig. 18).

|

|

|

In addition to the sarcomatous elements, these tumors also contain epithelial malignancies, either squamous or adenocarcinoma. Because they arise in the area of the endometrium, adenocarcinoma is the most common epithelial malignancy. Table 5 lists the reported frequency of the various malignant components. Leiomyosarcoma is the most commonly reported homologous component; rhabdomyosarcoma is the most frequently reported heterologous sarcoma. Adenocarcinoma is the most common epithelial malignancy.

TABLE 5. Frequency of Components in Mixed Malignant Müllerian Sarcomas

|

|

|

| Sarcoma | |

| Homologous Elements (%) | Heterologous Elements (%) | |||

|

| Endolymphatic |

|

|

|

| Leiomyo- | Stromal | Chondro- | Osteo- | Rhabdo- |

Author | sarcoma | Sarcoma | sarcoma | sarcoma | sarcoma |

Sternberg et al74 | 38.1 |

| 19.0 |

| 42.9 |

Rachmaninoff and Climie57 | 43.3 |

| 13.3 | 6.7 | 66.7 |

Norris et al72 |

|

| 58.0 | 13.0 | 55.0† |

Schaepmann-Von Geuns79 |

|

| 51.0 | 12.0 | 51.0 |

Kempson and Bari12 | 44.4 | 63.9 | 46.7 | 13.3 | 40.0 |

Williamson and | 68.1 | 42.6 | 28.6 | 21.4 | 67.9 |

Christopherson73 |

|

|

|

|

|

Blythe et al19 | 63.6 | 27.3 | 25.0 | 50.0 |

|

* 13 were listed in other categories.

† Listed as striated muscle.

PROGNOSIS.

The prognosis for gynecologic malignancies depends on three factors: histology, cellular differentiation, and the amount of disease present.

Once more than 10 mitotic figures per 10 HPF have been demonstrated, further cellular differentiation of these sarcomas is unimportant. The presence or absence of certain histologic types has been reported to be of some significance. Various authors have reported that survivors had no areas of rhabdomyosarcoma or osteosarcoma. However, cartilage (chondrosarcoma) was present in all survivors.12,72 Because of this apparent difference in survival, we have recommended that carcinosarcomas and mixed heterologous mesodermal tumors be reported separately. Most authorities find no relation between the various heterologous elements and survival.11,57,70,73,77

The most important prognostic factor reported by most authors is the amount of disease. If the disease, regardless of the histologic type, is confined to the uterus, the prognosis is best. When the survival rate is corrected for the extent of disease, the histologic component lacks significance.64,80,81,82,83,84 The prognosis worsens as the extent of the disease increases.12,30,70,72,79 The reported 5-year survival ranges from 0 to 60%.46,73,79,80

LYMPH NODE INVOLVEMENT

In 1966, Aaro and associates11 studied 177 patients with uterine sarcomas and concluded that hematogenous spread may occur early and that lymphatic spread was relatively infrequent. In 1978, DiSaia and colleagues86 published one of the first articles devoted primarily to lymph node sampling in patients with uterine sarcomas. In 28 cases of Stage 1 and 2 uterine sarcomas, they reported a 35% incidence of pelvic node involvement. This study stimulated several researchers to investigate this question further. One hundred three patients were studied by Peters and associates.65 In 1984, they reported that 8 of 59 patients (14%) undergoing surgical exploration had nodal metastasis. Five patients had positive pelvic and para-aortic nodes, two patients had only positive pelvic nodes, and one patient had positive para-aortic and negative pelvic lymph nodes. Since 1970, 13 patients with various uterine sarcomas have had planned nodal sampling, and four patients (31%) had positive nodes.

Wheelock and colleagues,87 in 1985, studied leiomyosarcomas, mixed malignant müllerian sarcomas, and endometrial stromal sarcomas. Part of this study included pelvic and para-aortic node biopsies on 10 Stage 1 or 2 patients. Only two (20%) of these patients had nodal involvement.

In 1987, Major and associates88 presented the results of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. Their patient population consisted of 174 patients with mixed malignant müllerian sarcomas, Stage 1 and 2, who had node sampling as part of their surgical staging. Twenty-seven of these patients (15.5%) had positive nodes. In 1989, Chen85 reported on 20 patients (Stage 1) with planned para-aortic and pelvic node sampling. Nine of these patients (45%) had nodal disease. Six patients had both pelvic and para-aortic involvement, and three patients had only pelvic disease. Chen determined that the factors important in patients with positive nodes included leiomyosarcomas, age older than 65, and deep myometrial penetration.

REFERENCES

Nieminen U, Soderlin E: Sarcoma of the corpus uteri: Results of the treatment of 117 cases. Strahlentherapie 148: 57, 1974 |

|

Kimbrough RA: Sarcoma of the uterus: Factors influencing results of treatment. Am J Obstet Gynecol 28: 723, 1934 |

|

Novak E, Anderson DF: Sarcoma of the uterus: Clinical and Pathologic study of fifty-nine cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol 34: 740, 1937 |

|

Papanicolaou GN, Maddi FV: Observations on the behavior of human endometrial cells in tissue culture. Am J Obstet Gynecol 76: 601, 1958 |

|

Ober WH: Uterine sarcomas: Histogenesis and taxomomy. Ann NY Acad Sci 74: 568, 1959 |

|

Wilms M: Die Mischgeschwulste der Vagina und der Cervix Uteri (Traubige Sarkom), Heft 2, pp 97–167. Leipzig, Arthur Georgi, 1900 |

|

Virchow R: Die Krankhaften Geschwulste, Vol 2. Berlin, August Hirschwald, 1864 |

|

Blaustein A: Pathology of the Female Genital Tract, pp 322–340. New York, Springer-Verlag, 1977 |

|

Zenker FA: Uber die Veranderungen der Wikuhrlichen Muskel im Typhus Abdominalis: Nebst einem Excurs uber die Pathologische Neubildung Quergestreiften Muskelgewebes, pp 84–86. Leipzig, Vogel, 1864 |

|

Bartsich EG, Bowie ET, Moore JG: Leiomyosarcoma of the uterus. Obstet Gynecol 32: 101, 1968 |

|

Aaro LA, Symmonds RE, Dockerty MB: Sarcoma of the uterus. Am J Obstet Gynecol 94: 101, 1966 |

|

Kempson RL, Bari W: Uterine sarcomas: Classification, diagnosis and prognosis. Hum Pathol 1: 331, 1970 |

|

Coppleson M: Gynecologic Oncology Fundamental Principles and Clinical Practice, Vol 2, pp 591–607. New York, Churchill Livingstone, 1981 |

|

Gudgeon DH: Leiomyosarcoma of the uterus. Obstet Gynecol 32: 96, 1968 |

|

Randal CL: Sarcoma of the uterus. Am J Obstet Gynecol 45: 445, 1943 |

|

Evans N: Malignant myomata and related tumors of the uterus. Surg Obstet Gynecol 30: 225, 1920 |

|

Stearns HC, Sneeden VD: Leiomyosarcoma of the uterus. Am J Obstet Gynecol 95: 374, 1966 |

|

Montague ACW, Swartz DP, Woodruff JD: Sarcoma arising in a leiomyoma of the uterus. Am J Obstet Gynecol 92: 421, 1965 |

|

Blythe JG, Bari W, Buchsbaum HJ: Uterine Sarcoma--Clinico-Pathologic Study, St John's Mercy Medical Center, St Louis, MO, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, unpublished data, 1974 |

|

Christopherson WM, Williamson EO, Gray LA: Leiomyosarcoma of the uterus. Cancer 29: 1512, 1972 |

|

Corscaden JA, Singh BP: Leiomyosarcoma of the uterus. Am J Obstet Gynecol 75: 149, 1958 |

|

Norris HJ, Taylor HB: Postirradiation sarcomas of the uterus. Obstet Gynecol 26: 689, 1965 |

|

Mallory: Principles of Pathologic Histology, p 307. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1914 |

|

Proper MS, Simpson BT: Malignant leiomyomata. Surg Obstet Gynecol 20: 30, 1919 |

|

Silverberg SG: Leiomyosarcoma of the uterus. Obstet Gynecol 38: 613, 1971 |

|

Ellis PSJ, Whitehead R: Mitosis counting--a need for reappraisal. Hum Pathol 12: 3, 1981 |

|

Hemdal I, Frankendal B: Letter: Uterine sarcomas; a clinicopathologic study. Gynecol Oncol 22: 379, 1985 |

|

Laberge JL: Prognosis of uterine leiomyosarcomas based on histopathologic criteria. Am J Obstet Gynecol 84: 1833, 1962 |

|

Spiro RH, Koss LG: Myosarcoma of the uterus: A clinicopathological study. Cancer 18: 571, 1965 |

|

DiSaia PJ, Castro JR, Rutledge FN: Mixed mesodermal sarcoma of the uterus. Am J Roentgenol 117: 632, 1973 |

|

Jensen PA, Dockerty MB, Symmonds RE et al: Endometrial sarcoma (“stromal endometriosis”). Am J Obstet Gynecol 95: 79, 1966 |

|

Koss LG, Sprio RH, Brunschwig A: Endometrial stromal sarcoma. Surg Gynecol Obstet 121: 531, 1965 |

|

Baggish MD, Woodruff JD: Uterine stromatosis. Obstet Gynecol 40: 487, 1972 |

|

Norris HJ, Taylor HB: Mesenchymal tumors of the uterus. I. A clinical and pathological study of 53 endometrial stromal tumors. Cancer 19: 755, 1966 |

|

Gitstein S, Baratz M, David MP et al: Endometrial stromatosis of uterus: A clinicopathological study of five cases. Gynecol Oncol 9: 23, 1980 |

|

Greene RR, Gerbie AB: Hemangiopericytoma of the uterus. Obstet Gynecol 3: 150, 1954 |

|

Pedowitz P, Felmus LB, Grayzel DM: Vascular tumors of the uterus. II. Malignant vascular tumors. Am J Obstet Gynecol 69: 1309, 1955 |

|

Akhtar M, Kim PY, Young I: Ultrastructure of endometrial stromal sarcoma. Cancer 35: 406, 1975 |

|

Yoonessi M, Hart WR: Endometrial stromal sarcomas. Cancer 40: 898, 1977 |

|

Bard DS, Zuna RE: Sarcomas and related neoplasms of the uterine corpus: A brief review of their natural history, prognostic factors, and management (Review). J Obstet Gynecol Ann 10: 237, 1981 |

|

Smith ML, Faaborg LL, Newland JR: Dedifferentiation of endolymphatic stromal myosis to poorly differentiated uterine stromal sarcoma. Gynecol Oncol 9: 108, 1980 |

|

Piver MA, Rutledge FN, Copeland L et al: Uterine endolymphatic stromal myosis: A collaborative study. Obstet Gynecol 64: 173, 1984 |

|

Soper JT, McCarthy KS, Hinshaw W et al: Cytoplasmic estrogen and progesterone receptor content of uterine sarcomas. Am J Obstet Gynecol 150: 342, 1984 |

|

Siegal GP, Taylor LL, Nelson KG et al: Characterization of a pure heterologous sarcoma of the uterus: Rhabdomyosarcoma of the uterus. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2: 303, 1983 |

|

Fung CH, Yonan TN, Lo JW et al: Vascular spaces inendolymphatic stromal myosis. Gynecol Oncol 10:241.1980 |

|

Clement PB, Scully FE: Müllerian adenosarcoma of the uterus. Cancer 34: 1138, 1974 |

|

Roth LM, Pride GL, Sharma HM: Mullerian adenosar-coma of the utenne cervix with heterologous elements.Cancer37:1725, 1976 |

|

Carleton CC, Williamson JW: Osteogenic sarcoma of theuterus. Arch Pathol 72: 121, 1961 |

|

Daniel WW, Koss LG, Brunschwig A: Sarcoma botryoides of the vagina. Cancer 12: 74, 1959 |

|

Middlebrook LF, Tennant R: Rhabdomyosarcoma of the uterine corpus. Obstet Gynecol 32: 537, 1968 |

|

Kukla EW, Douglas GW: Rhabdomyosarcoma of the corpus uteri: Report of a case, associated with adenocarcinoma of the cervix, with review of the literature. Cancer5:727, 1952 |

|

Donkers B, Kazzaz BA, Meijering JH: Rhabdomyosarcoma of the corpus uteri. Am J Obstet Gynecol 114: 1025, 1972 |

|

Stout AP: Rhabdomyosarcoma of the skeletal muscles. Ann Surg 123: 447, 1946 |

|

Stobe GD, Dargeon HW: Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma of the head and neck in children and adolescents. Cancer 3: 826, 1950 |

|

Riopelle JL, Theriault JP: Sur une forme meconnue de sarcome des parties molles: Le rhabdomyosarcome alveolarie. Ann Anat Pathol 1: 88, 1956 |

|

Horn RC, Enterline HT: Rhabdomyosarcoma: A clinicopathological study and classification of 39 cases. Cancer 11: 181, 1958 |

|

Rachmaninoff N, Climie ARW: Mixed mesodermal tumors of the uterus. Cancer 19: 1705, 1966 |

|

Wolfe SA, Mackles A: Uncommon myogenic tumors of the female generative tract. Obstet Gynecol 22: 199, 1963 |

|

Peckham BM, Greene RR: Rhabdomyosarcoma of the uterus. Am J Obstet Gynecol 63: 1379, 1952 |

|

Jaffe N, Filler RM, Farber S et al: Rhabdomyosarcoma in children: Improved outlook with a multidisciplinary approach. Am J Surg 125: 482, 1973 |

|

Hilgers RD, Malkasian GD, Soule EH: Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma (botryoid type) of the vagina. Am J Obstet Gynecol 107: 484, 1970 |

|

Davos I, Abell MR: Sarcomas of the vagina. Obstet Gynecol 47:342; 1976 |

|

Guersant MP: Polypes du vagin chez une petite fille de treize mois. Moniteur Hopitaux 2: 187, 1854 |

|

Pfannenstiel J: Das traubige Sarkom der Cervix uteri. Virchows Arch [A] 127: 305, 1892 |

|

Peters WA, Kumar NB, Fleming WP et al: Prognostic features of sarcomas and mixed tumors of the endometrium. Obstet Gynecol 63: 550, 1984 |

|

Rutledge F, Sullivan MP: Sarcoma botryoides. Ann NY Acad Sci 142: 694, 1967 |

|

Toker C: Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma: An ultrastructure study. Cancer 21: 1164, 1968 |

|

Symmonds RE, Pratt JH, Welch JS: Exenterative operations: Experience with 118 patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol 101: 66, 1968 |

|

Pratt CB, Hustu OH, Fleming ID et al: Coordinated treatment of childhood rhabdomyosarcoma with surgery, radiotherapy, and combination chemotherapy. Cancer Res 32: 606, 1972 |

|

Chuang JT, Vam Velden JJ, Graham JB: Carcinosarcoma and mixed mesodermal tumor of the uterine corpus. Obstet Gynecol 35: 769, 1970 |

|

Ober WB, Tovell HMM: Mesenchymal sarcomas of the uterus. Am J Obstet Gynecol 77: 246, 1959 |

|

Norris HJ, Roth E, Taylor HB: Mesenchymal tumors of the uterus. II. A Clinical and pathologic study of 31 mixed mesodermal tumors. Obstet Gynecol 28: 57, 1966 |

|

Williamson EO, Christopherson WM: Malignant mixed mullerian tumors of the uterus. Cancer 29: 585, 1972 |

|

Sternberg WH, Clark WH, Smith RC: Malignant mixed mullerian tumors (mixed mesodermal tumor of the uterus). Cancer 7: 704, 1954 |

|

Edwards DL, Sterling LN, Keller RH et al: Mixed heterologous mesenchymal sarcomas (mixed mesodermal sarcomas) of the uterus. Am J Obstet Gynecol 85: 1002, 1963 |

|

Schwartz Z, Dgani R, Lancet M et al: Uterine sarcoma in Israel: A study of 104 cases. Gynecol Oncol 20: 354, 1985 |

|

Carter ER, McDonald JR: Uterine mesodermal mixed tumors. Am J Obstet Gynecol 80: 368, 1960 |

|

Masterson JG, Kremper J: Mixed mesodermal tumors. Am J Obstet Gynecol 104: 693, 1969 |

|

Schaepmen-Van Geuns EJ: Mixed tumors and carcinosarcomas of the uterus evaluated five years after treatment. Cancer 25: 72, 1970 |

|

Mortel R, Koss LG, Lewis JL et al: Mesodermal mixed tumors of the uterine corpus. Obstet Gynecol 43: 248, 1974 |

|

Shimm DS, Bell DA, Fuller AF et al: Sarcoma of the uterine corpus: prognostic factors and treatment. RxTx & Onc 2: 201, 1984 |

|

Marchese MJ, Liskow AS, Crum CP et al: Uterine sarcomas: A clinicopathologic study, 1965-1981. Gynecol Oncol 18: 299, 1984 |

|

George M, Pejovic MH, Kramar A et al: Uterine sarcomas: Prognostic factors and treatment modalities-study on 209 patients. Gynecol Oncol 24: 58, 1986 |

|

Wen BS, Tewfik FA, Tewfik HH et al: Uterine sarcoma: A retrospective study. J Surg Oncol 34: 104, 1987 |

|

Chen SS: Propensity of retroperitoneal Iymph node metastasis in patients with stage I sarcoma of the uterus. Gynecol Oncol 32: 215, 1989 |

|

DiSaia PJ, Morrow CP, Boronow R et al: Endometrial sarcoma: Lymphatic spread pattern. Am J Obstet Gynecol 130: 104, 1978 |

|

Wheelock JB, Krebs HB, Schneider V et al: Uterine sarcoma: Analysis of prognostic variables in 71 cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol 151: 1016, 1985 |

|

Major F, Silverberg S, Morrow P et al: A preliminary analysis of prognostic factors in uterine sarcoma: A gynecologic oncologic group study (abstr), p 20. 18th annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Oncologists. Miami, Florida, 1987 |