Male Sterilization

Authors

INTRODUCTION

Vasectomy is well recognized worldwide as one of the safest and most effective contraceptive methods. It is one of the few contraceptive options for men. Risks associated with vasectomy are few and no greater than those found with any of the contraceptive options for women. In 2011, over 28 million married women were relying on their partners’ vasectomy for contraception.1 Although most vasectomies are performed in a small number of countries, the distribution of users is becoming increasingly widespread.1 In 2002, an estimated 526,501 vasectomies were performed in the United States; these figures have remained fairly stable over the past decade.1, 2

Tubal ligation is more widely used than vasectomy. Compared to the 28 million married women relying on vasectomy in 2011, an estimated 223 million women rely on female sterilization worldwide.1 In the US, 12.7% of married women reported partner vasectomy as their contraceptive method compared to 23.6% of married women who relied on tubal ligation for contraception in 2011.3 In most countries, couples using female sterilization for contraception outnumber those using male sterilization. However, in several countries, vasectomy incidence approaches that of female sterilization. For example, in Canada the contraceptive prevalence rate for male sterilization among married women was 21.0% in 2011 compared to 22.0% of currently married women using female sterilization that year. Similarly in Denmark, the estimated proportion of married women relying on vasectomy and those relying on female sterilization is 5% for both methods of contraception.3 In a few countries, namely the United Kingdom, Bhutan, Spain, The Netherlands, and New Zealand, the proportion of married women who report partner vasectomy as their contraception method exceeds those that rely on female sterilization.3

Despite commonly held assumptions about negative attitudes or societal prohibitions against vasectomy, when vasectomy is properly presented, men in every part of the world and from all cultural settings, religious affiliations and socio-economic status have demonstrated interest in or acceptance of the procedure.4, 5, 6 Several factors appear to be of critical importance in men’s vasectomy decision making. Men's desire to limit family size and their concern for economic and educational advancement must outweigh their desire for more children, and their concerns about maternal morbidity and the failure of female contraceptive methods must be an overriding consideration. In some cases, couples seeking vasectomy are dissatisfied users of other forms of contraception. Many couples find barrier methods inconvenient. Women using hormonal methods may have suffered from related side-effects or experienced user difficulties such as limited access to pill supplies or trained providers for implants. Intrauterine devices also have associated side-effects.

In the past 40 years, immunologic response and effects of vasectomy on lipid metabolism, spermatogenesis, epididymal function, and hormone levels have been studied. Concerns of potential long-term complications following vasectomy, including increased risk for heart disease, testicular cancer, immune complex disorders, and a host of other conditions, have not been supported by long-term, well-designed epidemiologic studies. The relation between vasectomy and prostate cancer has been studied intensely and, taken as a whole, these studies provide little evidence for a causal association between vasectomy and prostate cancer. (GLOWM Chapter Long Term Risks of Vasectomy)

HISTORY

A detailed history of vasectomy was published by Sheynkin in 2009.7 Briefly, the first experiment in tying of the vas was reported as early as 1785, but it was not until the 19th century that several investigations into the effects of vasectomy were undertaken. In 1830, Cooper reported results of the first systematic study on vasectomy when he demonstrated that closing the duct of the testis had no effect on sperm production, confirmed by additional studies in the 1920s and 1940s by Simmonds and Gosselin, respectively. In the late 1890s, investigation of the clinical uses of vasectomy was begun by surgeons in conjunction with therapeutic operations on the prostate gland. Ochsner reported no change in sexual function of his patients following vasectomies. In the 1920s, Rolnick studied the regenerative power of the vas and emphasized the importance of the blood supply and the sheath of the vas acting as a splint making a path of epithelialization during recanalization after vas ligation. This classic work still has pertinence today in our efforts to achieve successful vas occlusion and to reduce the chance of failure, and informs us about the potential for successful vasectomy reversal when indicated. The first mention in the medical literature of vasectomy as a voluntary contraceptive option was by O’Connor in 1948.

COMMUNITY AWARENESS ABOUT VASECTOMY

The level of awareness of the community about a service or a family planning method has an impact on whether those that may benefit from the method can seek out more information or the actual service. Level of knowledge about a method has been shown to contribute to the decision on choice of a method.8 Several studies from different countries have documented inadequate information, misinformation or lack of information about vasectomy among men and women of reproductive age, more so than among other contraceptive methods. Recent demographic and health surveys from several countries particularly in sub Saharan Africa report levels of knowledge on male sterilization among men and women of reproductive age ranging from 10% to 50%;9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 only in Rwanda, Malawi and Uganda were the levels of knowledge on male sterilization over 50% (ranges between 53% and over 70%).18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 The rates are much lower compared with those reported in India, for example, where knowledge on male sterilization among men and women is almost universal.8

A study in Kigoma Tanzania, where vasectomy uptake is higher than in the rest of the country, reported that spousal influence was important in the decision making process; spousal influence was also found to be important in Ghana.24, 25 In contrast, both male and female married youth (18–24 years) in Karachi, Pakistan had many myths and fallacies about vasectomy in particular relative to other methods.26 Demand creation programming should therefore target both men and women. In the United Kingdom where knowledge about vasectomy is almost universal, the guidelines from the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists recommends that women who are interested in limiting future births should be informed that vasectomy carries lower risks of failure and that there are fewer risks related to the procedure compared to tubal ligation.27

Several innovations for engaging the community have been adopted to promote vasectomy use specifically or involvement of men in family planning more generally, with varying levels of success. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, several vasectomy promotional projects were undertaken in a number of countries in Latin America and Africa. Successes as witnessed by a dramatic increase in number of vasectomy procedures following systematic and intensified vasectomy promotion were reported in Brazil, Guatemala, Mexico and Colombia, although in other countries in the Latin American region and sub Saharan Africa in particularly, the number of vasectomies have remained relatively low despite the promotional activities. However, it is important to note that wherever vasectomy has been introduced in sub Saharan Africa, it has been accepted by at least some men.4, 28

Vasectomy promotion techniques that have been used in various countries include mass media, bill boards, posters, fliers and pamphlets, other materials with printed slogans, pronouncements at public meetings, soap opera, champions (satisfied vasectomy clients), campaigns, discussions on social media and, more recently, the introduction of the World Vasectomy Day that is to be marked annually. Vasectomy promotional activities similar with other demand generation activities should be informed by research or needs assessments, and definition of objectives for the intervention and the segment of the population to benefit from the intervention. It is critical to ensure availability of quality family planning services and that there is adequate capacity to offer vasectomy services and other methods to clients who respond to the demand generation efforts.

Some of the major challenges of vasectomy promotional interventions include lack of sustained support for the introduction and promotion of vasectomy particularly in sub Saharan Africa, addressing provider biases and lack of up to date information on the method among providers, and limited interest among development partners.4, 29 Results of a study on the attitudes, counselling patterns and acceptance of vasectomy among Nigerian resident gynecologists showed that the practitioners were knowledgeable about vasectomy, however, most did not routinely counsel client about vasectomy. The study recommended targeting resident doctors with quality training on vasectomy to enhance knowledge on vasectomy and a positive attitude towards vasectomy.30 In Ghana, improving provider knowledge and attitudes about vasectomy, coupled with health promotion resulted in an increase in the proportion of men considering the method as well as a threefold increase in number of vasectomies conducted by trained providers.6

COUNSELLING FOR VASECTOMY

The process of counselling a client or couple seeking vasectomy is a continuous process that begins during the pre-vasectomy period and continues during the procedure and after the procedure in the postvasectomy period. During pre-vasectomy counselling, the goal of the counselling session is to ensure that the client has the appropriate expectations of what will happen in the pre-, intra- and postoperative operative periods and the consequences of the vasectomy.1 One survey conducted inthe USA, to explore the experiences of sterilization counselling among male and female clients and their perspectives on ideal counselling showed that most female clients reported being counselled about female sterilization, while the men were mainly counselled on vasectomy. Both men and women in the study desired more information about vasectomy particularly in relation to its effect on sexual desire and moods, side effects, pain during the procedure, safety and efficacy. Further, study respondents said long acting reversible methods were not routinely discussed during counselling.31 Although the study population was small, the findings are similar to other studies conducted elsewhere on quality of counselling. The counselling process should ensure that the client is aware of all contraceptive choices. Where applicable, the counselling should involve both partners.

The client's decision for vasectomy must be made voluntarily and after the consideration of all of the risks, benefits and alternatives. Good counselling for men interested in vasectomy is critical for two reasons: vasectomy is permanent, and vasectomy is a surgical procedure that carries with it the risks inherent in any surgery. Because men's greatest fears about vasectomy are related to pain of the procedure, impact on sexual functioning, and potential for adverse effects,32 these topics should be thoroughly covered during counselling. Clients should also be informed of the small risk of pregnancy after vasectomy even in clients who have postvasectomy azoospermia several years after the procedure.1, 27, 33 During counselling, the following key points should be covered.34, 35, 36

1. Discussion and explanation of all other available contraceptive options.

2. The client’s readiness to end his fertility and screening for indicators of poststerilization regret. Factors shown to predispose to poststerilization regret include young age (less than 31 years), quick or economically motivated decision or decision related to pregnancy, marital instability, and no children or children very young at the time of sterilization.37, 38, 39 The provider should explore with the individual whether he would feel differently if his marital situation changed or if he lost his spouse or a child. Identifying regret risks should not be a reason for denying vasectomy but should be an indicator that more careful counselling and discussion of other contraceptive methods are necessary.

3. The effectiveness and permanence of vasectomy. Inform the client of failure rates associated with vasectomy (1 in 2000). Despite what the client may have heard about vasectomy reversal, it is expensive, and success cannot be guaranteed. If a client considering vasectomy is seriously thinking about reversal, a vasectomy may not be the best procedure for him at this time. Likewise, if a man asks to have his sperm stored in a sperm bank for the future, mention to him that this is costly, that viable long-term storage is not without risk, that pregnancy with stored sperm cannot be guaranteed, and that he may want to reconsider vasectomy.

4. Description of the vasectomy procedure: Using diagrams, briefly describe the vasectomy procedure and how contraception is achieved. Describe to the client the surgical site, time the procedure usually takes, type of anesthesia, length of recovery, and resumption of sexual activity. Discuss general surgical risks. Emphasize that vasectomy is not effective immediately and that the client should use an alternate method of contraception until his semen is tested and found to be free of sperm.

5. Medical benefits and risks of vasectomy. Discuss fears and myths that are prevalent in the geographical location regarding the long-term health effects of vasectomy. Although the body of research suggests that vasectomized men are no more likely than nonvasectomized men to develop heart disease and cancer, preventive lifestyle and screening should be addressed. Emphasize that vasectomy provides no protection against sexually transmitted infections, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.

Point out that vasectomy does not cause a loss in physical strength, development of a high pitched voice, a loss or change in sexual function, weight gain, or a loss of masculinity. Inform the client that he will still ejaculate after surgery and in the same amount. The semen will not, however, contain any sperm after successful vasectomy. Some studies have indicated that sexuality may improve because couples do not worry about accidental pregnancy.

6. Preoperative evaluation: Inform the client about the need for an evaluation of his health status and fitness for the vasectomy procedure.

7. Cost of the service(s): Tell the patient about any fees he is expected to pay. Ensure compliance with local, state, and institutional restrictions regarding age, waiting periods, and second opinions.

8. Preoperative instructions: clients should be educated on what they should do to prepare themselves for the surgery and recovery. Such instructions should be verbal and in writing. On the day of surgery, the client should bathe or shower and wear loose-fitting clothing. If necessary, hair on the scrotum should be clipped immediately before the procedure and not by the client at home. The client should bring an athletic supporter or briefs to wear after the surgery.

9. Postoperative recovery and follow up instructions: Explain to the client what to expect during the postoperative period and how to manage pain and discomfort. Clients should also be educated on the early signs of complications and what to do when they experience such problems. The counsellor should also educate the client on the follow up schedule and investigations to be done during this period.

Throughout the discussion, the counsellor should answer client questions and concerns. Use diagrams and pictures of instruments to reduce patient anxiety. Emphasize that vasectomy is a safe, simple, and highly effective procedure. As appropriate, compare and contrast the cost of vasectomy with other available contraceptive methods.

The counsellor should also provide printed educational materials that the client and his partner can review privately, as well as oral and written preoperative instructions. Preoperative vasectomy patients must avoid aspirin-containing drugs for 2 weeks before and 1 week after surgery.40 The client must also undergo a limited physical examination (detailed in the section below). Laboratory tests (e.g. blood count, bleeding and clotting time, blood glucose levels, urinalysis or other tests) are not routine, but may be necessary for specific cases when a clinical abnormality is suspected that might necessitate delay of the procedure or that special precautions be in place.

The counselling performed during the procedure involves reassuring the client, explaining each step of the procedure and informing the client of what to expect. The surgical team may also communicate with the client to distract him during the procedure by discussing social issues or other topics as a way of allaying his anxiety.

In the immediate postoperative period, the counselling process should include demonstration of empathy to the client as appropriate (e.g. if he is experiencing pain or anxiety), explanation of the need for a short period of rest once he returns home and the required home care, as well as signs of potential complications and what to do should they arise. Explain the follow up schedule and ensure that the client has fully understood the postoperative instructions and can recite them. Counselling should also include use of alternative contraception before semen analysis confirms azoospermia and how to prevent sexually transmitted infections. Clients should be educated on the importance of the return visit. All instructions should also be given to the client in writing. In the late postoperative period, after the semen analysis, the client should be informed of the outcome of the test and the implications of the semen analysis results.

DOCUMENTING INFORMED DECISION MAKING

Before a client undergoes the surgical procedure, it is a requirement that he consents in writing. In some countries for medico legal reasons, the provider or counsellor is expected to clearly document the preoperative discussions as part of the client’s notes.27 In most countries, the consent of the spouse or partner is not mandatory before vasectomy can be performed. Further, the client signs an informed consent form on the day of surgery to indicate that he has reviewed the information given him and discussed his decision with the vasectomy provider. The client must understand the seven points of informed decision making listed below and know what he is signing. The provider should encourage the client to ask questions. The seven points of informed decision making are:41

1. Temporary contraceptive methods are available to the client and his partner.

2. Vasectomy is a surgical procedure.

3. There are certain benefits and risks associated with vasectomy, including the small risk of failure, both of which must be explained.

4. The effect of vasectomy is to be considered permanent.

5. If successful, vasectomy will prevent the client from having any more children.

6. Vasectomy does not protect the client or his partner from sexually transmitted infections, including HIV.

7. The client can decide against the operation at any time before the procedure without losing the right to other medical, health, or other services or benefits.

The client's signature or mark should be obtained. For clients who are illiterate, a mechanism should be in place for the content of the form to be discussed in a language he understands. Also, if the client is illiterate, the provider should obtain a witness's signature attesting that the client has affixed his mark or thumbprint on the informed consent form.

There should be no rigid guidelines concerning waiting periods before vasectomy is performed. Informed consent can be obtained at any time prior to the vasectomy. Counselling, informed consent, and the vasectomy procedure may occur on the same day or on different days, depending on various factors such as the client’s wishes, the distance the client has to travel to the clinic, the clinic’s scheduling needs, etc. What is important is that the client be given the time that he (and his partner, as applicable) needs to make an informed and voluntary decision regarding vasectomy.

ANATOMY

The male reproductive organs include the testicles, the ducts, the penis, and the accessory glands (Fig. 1). The testicles produce sperm and the hormones testosterone and inhibin. After vasectomy, the testes continue to produce both sperm and hormones.

|

Sperm pass through a series of connected ducts: the epididymides, the vasa deferentia, and the urethra. Each of the two epididymides (which begin at and are connected to the testes) are connected to one of the vasa deferentia. Sperm pass through the epididymis to get from the testis to the vas and are also stored in the most distal portion, or tail, of the epididymis. Sperm become motile and acquire the ability to fertilize ova during transport through the epididymides. The vasa begin at the epididymides and end at the base of the prostate, where they come together and are connected to the urethra and the accessory glands. Here, the sperm, which were carried by the vasa deferentia, mix with secretions from the accessory glands. The urethra carries the semen (i.e. sperm contained in the secretions from the accessory glands) out of the body during ejaculation. The urethra also carries urine.

The accessory glands include the seminal vesicles, the prostate, and the bulbourethral glands. These glands secrete the seminal fluid that carries sperm through the urethra during ejaculation.

The vas deferens is a firm, tubular structure approximately 3–4 mm in diameter and approximately 35 cm in length. It extends from the tail of the epididymis to the prostate, where, together with the duct of the seminal vesicle, it forms the ejaculatory duct.

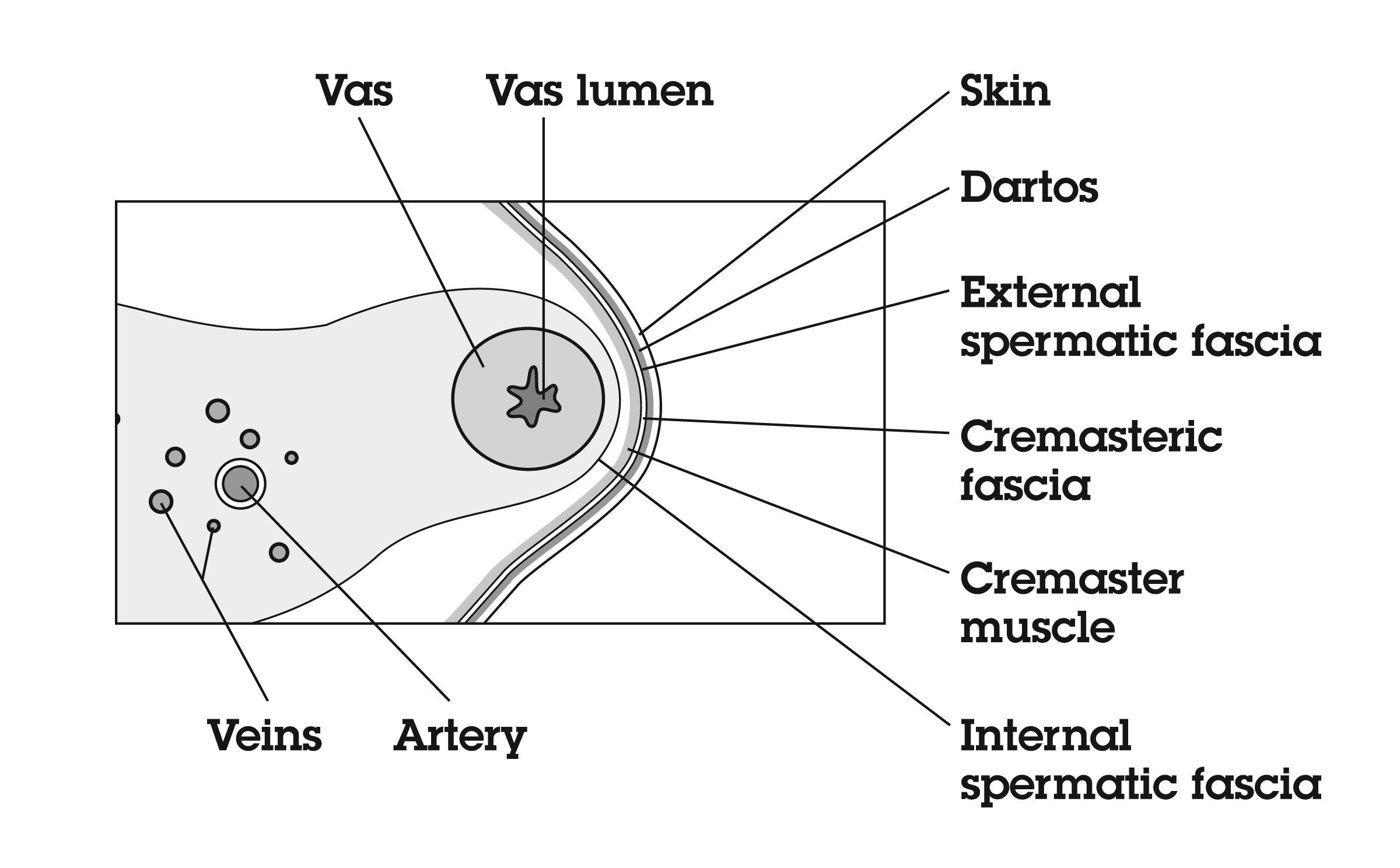

The vas deferens may be divided into five portions: the sheathless epididymal vas, the scrotal vas, the inguinal vas, the retroperitoneal or pelvic vas, and the ampulla (Fig. 2). The portion of the vas of clinical interest in relation to vasectomy is the scrotal vas in the mid-scrotal area. Here the vas is located within the spermatic cord, which is made up of fascia, arteries, veins, and nerves and which suspends the testis in the scrotum (Fig. 3). The firm, thick structure of the vas can be easily palpated and differentiated from other structures in the spermatic cord. Also in the spermatic cord is the testicular artery, which supplies blood to the testis and epididymis, and the testicular veins, which form the pampiniform plexus that returns blood from the testis and epididymis.

|

|

The vas deferens is composed of three layers of smooth muscle: the outer and inner longitudinal layers and the middle circular layer. It is capable of powerful peristaltic motion. There is a thick sheet of connective tissue exterior to the muscle layer. The lumen of the vas, like that of the epididymis, is lined with pseudo-stratified epithelium and contains longitudinal folds lined with microvilli.

The blood supply of the vas deferens is from the artery of the vas deferens (deferential artery), a branch of the superior vesical artery that is also important in collateral circulation for the testicle. This artery is easily separated from the vas during vasectomy; however, it may be a source of hemorrhage during vasectomy if it is not separated or ligated.

The nerves of the testes (the superior spermatic nerves) arise from the renal plexus and intermesenteric nerves and travel in association with the testicular arteries, whereas the inferior spermatic nerves arise from the hypogastric plexus and course around and along the vas deferens to innervate the epididymides. At the junction of the epididymis and vas deferens, the amount of adrenergic innervation increases, with innervation of the vas consisting of short, postganglionic neurons. Adrenergic fibers, which are found in all three smooth muscle layers, are most likely the motor supply of the vas muscle. The sheath of the vas in the scrotal portion contains pain nerves. Careful infiltration of the sheath with local anesthetic agents is effective in reducing pain during the procedure.

Blood vessels and nerves involved in erection and ejaculation, including the internal pudendal artery, dorsal and cavernous veins, pudendal nerves (sensory nerves to the penis), and nerves from the pelvic plexus arising from sacral nerves S2–S4 (nerves involved in erection), are located well away from the procedure site and are therefore unaffected by vasectomy.

Anatomical anomalies of the male organs of significance include cryptorchidism (undescended testis), duplicate vasa, varicocele, hydrocele and inguinal hernia.

PREOPERATIVE SCREENING AND EVALUATION

The main purpose of the preoperative screening and evaluation of a client seeking vasectomy is to assess the client’s readiness for a vasectomy procedure under local anesthesia. The screening process also enables the provider to identify any pathology that may be a contraindication for the vasectomy under local anesthesia or conditions that require further investigations and/or management before surgery. For example an extremely anxious client may benefit from an alternative pain management option. The evaluation also enables the provider to apply the eligibility criteria that has been approved by relevant authorities in that country to chart the management of the client. Ideally, the evaluation should be done on the day of the counselling before the client is prepared for surgery or at a later date or on the day of the surgery.1 Table 1 lists the required and recommended components of a pre-vasectomy medical history and physical examination and explains the reason each component is included.

Table 1. Components of a pre-vasectomy medical history and physical examination.

| Component | Reason |

| Medical History |

|

| General medical history | Obtaining such history will help the provider to be aware of and where applicable assess pre-existing medical conditions and plan for the surgery as appropriate |

| Age | Men who are too young, i.e. below 30 years particularly if they are unmarried, are likely regret the decision to have vasectomy later in life. It is important to ensure that these clients have an adequate opportunity to consider alternate contraceptive options. |

| Existence of bleeding disorders | Can indicate the potential for hemorrhage |

| Previous scrotal or inguinal surgery or trauma | Scarring or adhesions that could complicate a vasectomy procedure may exist |

| Current or past genitourinary infections, including sexually transmitted infections | Past infections could have caused scarring and adhesions; current infection could lead to acute postvasectomy infection |

| History of sexual impairment | Can indicate pre-existing psychological or physiologic problems that could later be incorrectly attributed to the vasectomy |

| Current and recent medications | Can indicate medical problems that the provider should be aware of before surgery |

| Allergy to medications | Can help prevent complications by determining whether the client has ever had an allergic reaction to any of the medications or antiseptics used before, during, or after surgery |

| Physical Examination |

|

| General condition of client | Can provide information about the nutritional status of the client, level of hydration, existence of anemia, jaundice, fever, or hypertension |

| Lungsa (auscultation and respiratory rate) | Can rule out infections and other lung disease that the vasectomy provider should be aware of before surgery |

| Hearta (auscultation, pulse, and blood pressure) | Can rule out hypertension, heart murmurs, and other cardiovascular disease that the vasectomy provider should be aware of before surgery |

| Abdomena (palpation) | Can rule out the presence of infections, organ enlargements, or masses that the vasectomy provider should be aware of before surgery |

| Genitals | Can rule out the presence of infections or masses that the vasectomy provider should be aware of before surgery |

a Recommended but not essential depending on the medical history

ASSESSMENT OF THE GENERAL CONDITION OF THE CLIENT

The provider should be prepared to perform the evaluation of the client by having the necessary supplies and equipment. As is the standard practice, the provider should seek verbal consent to examine the client after explaining the purpose of such an assessment and what the client needs to do to assist the provider to perform the evaluation. During examination of a client, the provider must adhere to standard infection prevention practices and apply hand hygiene and/or barriers such as examination gloves where appropriate. The provider should also maintain confidentiality and right to privacy during the assessment.

A quick assessment of the general condition of the client including measurement of vital signs should be done. Where applicable, this should be followed by the examination of the client's heart, lungs, and abdomen. The examination of the lower abdomen may require that the pubic area is exposed and existence of an inguinal hernia or other masses be ruled out before a more detailed assessment of the external genitalia is performed.

GENITAL EXAMINATION

The general examination should begin by good exposure and inspection of the external genitalia including the groin. A genital examination includes a detailed assessment of the penis, the scrotum and its contents, and the groins including the pubic area, for any lesions. The provider should inspect and palpate any abnormal masses or lesions in the groin and the pubic area.

PENILE EXAMINATION

The penis is visually inspected, and any lesions (such as rashes, swellings or ulcers, warts) or scarring are further assessed and noted. The urethral opening should also be examined. Any abnormalities such as discharge, reddening, or irritation are noted and assessed.

SCROTAL EXAMINATION

The scrotal skin is visually inspected. The scrotum is lifted to examine the posterior side. Pigmentation, size, contour, and presence of scars or ulcers are observed. Any swelling or masses are further assessed by palpation and noted. Some of the conditions to look for during the assessment include rash, hyper- or hypopigmentation, skin infections, ulcers, existence of a surgical scar(s), hydrocele or cysts, tortuous blood vessels or varicocele, poorly developed scrotum (possible cryptorchidism or undescended testis), and swelling (possible inguinal hernia, torsion of spermatic cord, strangulated inguinal hernia).

PALPATION OF THE TESTIS AND EPIDIDYMIS

Using the thumb and first two fingers, the provider palpates each testis and epididymis (Fig. 4). He or she avoids putting pressure on the testis during the palpation so as not to cause pain. The size, shape, mobility and consistency of each testis and epididymis are noted. Any nodules or tenderness are also noted.

Painless nodules in the testes may indicate testicular cancer. Nodules in the epididymis may indicate an epididymal cyst (seminoma).

PALPATION OF THE SPERMATIC CORD AND VAS DEFERENS

Each spermatic cord and its vas deferens should be located by palpation (Fig. 5). The health care provider then moves his or her thumb and fingers along its length to determine its consistency, mobility, areas of tenderness, and any masses. Any difficulties in the location of the vas within the spermatic cord or restricted mobility, excessive tenderness, nodules or masses are noted. Potential abnormalities include thickened vas (suggests chronic infection), tortuous veins (suggests varicocele), and cyst in the cord (suggests hydrocele).

PRECAUTIONS

Although vasectomy is a simple operation that can be performed almost anywhere, the more removed the setting is from medical back-up, the more important it is to screen out men who are likely to develop complications.

The major physical precautions to performing vasectomy are local skin infection or other systemic infections, gastroenteritis and systemic blood disorder. Local skin infection, which can prevent normal healing or increase risk of postoperative infections, is easily recognized and should be treated and the condition resolved before the operation is performed. Other local conditions that make vasectomy more difficult to perform include inguinal hernia, previous surgery for hernia or orchiopexy (also known as ochidopexy), hydrocele, varicocele, pre-existing scrotal lesions, and a thick, tough scrotum.

Systemic blood disorders that call for special precautions include any disease that interferes with normal blood clotting (e.g. hemophilia). In such cases, the vasectomy technique used should minimize tissue trauma, and emergency equipment should be available. If the client is taking anticoagulants, the same precautions may be required. Other systemic diseases, such as diabetes, hypertension, or other cardiac disease, are not contraindications to vasectomy, but hospitalization and intraoperative monitoring with prolonged close observation and follow-up are advisable in case emergencies arise. Table 2 presents the World Health Organization's (WHO) eligibility criteria for vasectomy procedures,42 which include standard vasectomy precautions.

Table 2. WHO eligibility criteria for vasectomy procedures

| There is no medical reason that would absolutely restrict a person's eligibility for sterilization. There may be conditions and circumstances that indicate that certain precautions should be taken. | ||

| The classification of the conditions into the different categories is based on an in-depth review of the epidemiologic and clinical evidence relevant to medical eligibility. | ||

| Definitions |

| |

| A (Accept): | There is no medical reason to deny sterilization to a person with this condition | |

| C (Caution): | The procedure is normally conducted in a routine setting, but with extra preparation and precautions | |

| D (Delay): | The procedure is delayed until the condition is evaluated and/or corrected. Alternative temporary methods of contraception should be provided | |

| S (Special): | The procedure should be undertaken in a setting with an experienced surgeon and staff, equipment needed to provide general anesthesia, and other back-up medical support. For these conditions, the capacity to decide on the most appropriate procedure and anesthesia regimen is also needed. Alternative temporary methods of contraception should be provided if referral is required or there is otherwise any delay | |

| Condition | Category | Rationale/Comments |

| Young age | C | Young men are more likely to request vasectomy reversal |

| Depressive disorders | C | Decision making may be affected |

| High risk of HIV | A | No routine screening is needed. Appropriate infection procedures must be carefully observed with all surgical procedures |

| HIV-positive | A | No routine screening is needed. Appropriate infection procedures must be carefully observed with all surgical procedures |

| AIDS | S | The presence of an AIDS-related illness may require a delay in the procedure |

| Local infections (scrotal skin infection, active STI, balanitis, epididymitis or orchitis) | D | There is an increased risk of postoperative infection |

| Previous scrotal injury | C | Depending on extent of the injury and subsequent wound healing process, the anatomy may have been distorted making it difficult to locate and isolate the vas |

| Systemic infection or gastroenteritis | D | There is an increased risk of postoperative infection, complications from dehydration, and anesthesia-related complication

|

| Large varicocele | C | The vas may be difficult or impossible to locate; a single procedure to repair the varicocele and perform a vasectomy decreases the risk of complications |

| Large hydrocele | C | The vas may be difficult or impossible to locate; a single procedure to repair the hydrocele and perform a vasectomy decreases the risk of complications |

| Filariasis; elephantiasis | D | If elephantiasis involves the scrotum, it may be impossible to palpate the spermatic cord and testis |

| Intrascrotal mass | D | This may indicate an underlying disease |

| Cryptorchidism | C | If cryptorchidism is bilateral, and fertility has been demonstrated, this will require extensive surgery to locate the vas, making the condition category S. If cryptorchidism is unilateral and fertility has been demonstrated, vasectomy may be performed on the normal side and sperm analysis performed, as per routine. If sperm continue to be persistently present, more extensive surgery may be required to locate the other vas, and the condition becomes category S |

| Inguinal hernia | S | Vasectomy can be performed concurrent with hernia repair |

| Sickle-cell disease | A | No routine screening is needed. Appropriate infection procedures must be carefully observed with all surgical procedures |

| Coagulation disorders | S | Bleeding disorders lead to an increased risk of postoperative hematoma formation which, in turn, leads to an increased risk of infection |

| Diabetes | C | Diabetics are more likely to get postoperative wound infections. If signs of infection appear, treatment with antibiotics needs to be given |

(Adapted from World Health Organization (WHO): Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use. Fourth edition. Geneva: WHO, 2010.)

VERIFYING INFORMED CONSENT

Just prior to surgery, the surgeon should verify that the client has signed an informed consent form. The guide presented in Fig. 6 can be used in making a final assessment of the client's informed decision to have a vasectomy.

TECHNIQUES

There are two key surgical steps for performing vasectomy; isolation of the vas, followed by occlusion of the vas. The two most common methods for isolation of the vas are conventional incisional vasectomy and the no-scalpel vasectomy (NSV) technique.1 However, the most recent American Urological Association guidelines define a third technique namely, minimally invasive vasectomy (MIV).1 The guidelines for AUA currently recommend that isolation of the vas should be performed using NSV or another minimally invasive technique. A summary of the different techniques for isolating and occluding the vas are described below.

Approaches to isolation of the vas

Conventional vasectomy is performed under local anesthesia. The infiltration of the local anesthesia is at the operation site and not perivasal. A scalpel is then used to make either one midline incision or two incisions overlying each vas deferens; the incision or incisions are 1.5–3 cm long (Fig. 7). No special instruments are used to grasp the vas, the vas is grasped using the towel clip or Allis forceps. The dissection to locate the vas involves a much wider area than with NSV or other MIVs. After occlusion of the vasa using the surgeon's preferred technique, the incision or incisions are closed with sutures.

No-scalpel vasectomy (NSV) is a method of delivering the vasa deferentia under local anesthesia that was developed and has been used in China since 1974.43, 44 It has been introduced in many developed and developing countries. In 2002, nearly 40% of physicians surveyed in the US reported they were currently using NSV and almost one half of all vasectomies performed in the US were no-scalpel vasectomies.2 Most vasectomies performed in Bangladesh, India and Nepal are with the NSV technique.45 This technique eliminates the need for use of a scalpel and instead utilizes two specialized instruments: a ringed clamp (Fig. 8) and dissecting forceps (Fig. 9). No-scalpel vasectomy involves a deep injection of local anesthetic applied alongside each vas, creating a vasal nerve block (Fig. 10). This is in contrast to conventional vasectomy techniques, in which only the area around the skin entry site is anesthetized. The size of the needle also matters and the 25–32 G is the recommended size for performing the vassal nerve block.1, 46 A jet injection technique has been described for vasectomy to deliver a high pressure spray of local anesthetic that minimizes the amount of anesthetic needed and results in almost immediate onset of anesthesia.47, 48 In studies of the use of this no-needle approach it was shown to significantly reduce pain of administration of anesthesia and was equally as effective in reducing pain during NSV, compared to injection of local anesthetic.48

|

|

|

The ringed clamp encircles and firmly secures the vas without penetrating the skin (Fig. 11). A sharp, curved hemostat (the dissecting forceps) punctures and spreads the scrotal skin and vas sheath. The vas is delivered, cleaned, and occluded using the surgeon's preferred technique (Fig. 12). The contralateral vas is then delivered through the same opening and occluded. The puncture wound contracts to about 2 mm, is not visible to the client, and requires no sutures for closure.

No-scalpel vasectomy offers several advantages over conventional vasectomy.49, 50 No-scalpel vasectomy results in fewer hematomas and infections compared with conventional vasectomy (Table 3).

Table 3. Incidence of infection and hematoma or bleeding after vasectomy

| Reference | No. of subjects | Infections (%) | Hematoma or bleeding (%) |

| Incisional |

|

|

|

| Philp et al 198451 | 534 | 1.3 | 4.5 |

| Kendrick et al 198752 | 65, 155 | 3.5 | 2.0 |

| Nirapathpongporn et al 199053 | 523 | 1.3 | 1.7 |

| Alderman 199154 | 1224 | 4.0 | 0.3 |

| Sokal et al 199955 | 627 | 1.3 | 10.7 |

| 51 | 11.4 | 15.9 | |

| No-Scalpel |

|

|

|

| Nirapathpongporn et al 199053 | 680 | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| Li et al 199143 | 179, 741 | 0.9 | 0.1 |

| Li et al 199143 | 238 | 0 | 0 |

| Sokal et al 199955 | 606 | 0.2 | 1.7 |

| Arellano et al 199757 | 1000 | 0 | 2.1 |

| 49 | 7.1 | 9.5 |

In a 1991 survey conducted in the United States, 78 out of 111 surgeons (70%) said they believed patients undergoing no-scalpel vasectomy with vasal block anesthesia experienced less operative pain than did patients undergoing conventional vasectomy.44 Indeed, men undergoing no-scalpel vasectomy reported less pain during the procedure and early follow-up period, and also reported earlier resumption of sexual activity after surgery.55, 58 Because there is no scrotal incision, no-scalpel vasectomy is believed to decrease men's fears regarding vasectomy.44

Neither conventional nor no-scalpel vasectomy is time consuming; however, there are reports of decreased operating time when skilled providers use the no-scalpel approach. For example, a study in Thailand showed that surgeons who used the no-scalpel technique were able to perform an average of 57 procedures per day, whereas those using the conventional technique performed an average of 33 procedures per day.53 Similarly, in the United States, a 40% reduction in operating time has been reported with no-scalpel vasectomy.43

Minimally invasive techniques (MIV): Methods with minor variations of the no-scalpel vasectomy technique are defined as minimally invasive techniques. The skin opening is also less than 10 millimeters and the provider uses special instruments to grasp the vas. Several such modifications of the NSV approach, successful in the investigator's hands, have been reported in the literature.59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64

Occlusion of the vas deferens

A variety of methods are currently used for occlusion of the vas, including ligation with sutures, division, cautery, clips, excision of a segment of the vas, folding back of a segment of the divided vas and combinations thereof. The same techniques are used to occlude the vas whether using a conventional vasectomy, NSV or MIV technique. Simple ligation without division and simple division alone are not recommended, because the potential for failure due to recanalization is high. There is little consensus regarding what occlusion technique is best. In the United States, for example, results of a survey indicated that occlusion technique varied: 41% of vasectomies were performed using ligation and cautery, 18% using cautery and clips, 17% using ligation only, 13% using cautery only, 9% using clips only, 2% using cautery, ligation and clips, and 2% using ligation and clips.2

This lack of consensus is partially due to the fact that good research data to support the use of any one technique over another were unavailable for many years.65, 66 Most reports in the literature are retrospective reviews of individual physicians' experiences of either a single occlusion method or sequential use of two methods. It is difficult to interpret some studies because details on definitions of failure, follow-up protocols, loss to follow-up rates, or statistical methods are often lacking. Although these factors also contribute to the difficulty in comparing results among studies, the fact that most studies use a different occlusion technique—ligation, clips, cautery, excision versus no excision, closed versus open, fascial interposition versus no fascial interposition, or different combinations of the various techniques—makes most comparisons across studies questionable.

Results from a number of studies in the early 2000s, however, suggest that there are some differences in effectiveness among different occlusion techniques. Several studies found higher than expected failure rates for vasectomy by ligation (with suture or clips) and excision of a segment of the vas.67, 68, 69, 70 Results of a randomized controlled trial demonstrated that use of fascial interposition (suturing the spermatic fascia over one end of the vas to place a tissue barrier between the two cut ends) with ligation and excision significantly improved the effectiveness of vasectomy compared to ligation and excision without fascial interposition. Therefore, the latter technique should no longer be recommended.71, 1

Mucosal electrocautery has been shown to be highly effective65, 72 and was found to significantly reduce failures compared to ligation and excision with fascial interposition.73 No major difference has been reported on effectiveness following use of thermal versus electrical cautery for vassal occlusion. Mucosal cautery (electrical or thermal) and fascial interposition has also consistently resulted in occlusive effectiveness and contraception.74, 75, 76

The American Urological Association guidelines published in 2012 recommend one of the following three vasal occlusive techniques for use: mucosal cautery with fascial interposition and without ligatures or clips applied to the vas; mucosal cautery without fascial interposition and without ligatures or clips applied to the vas; or open ended vasectomy leaving the testicular end of the vas un-occluded, with mucosal cautery on the abdominal end and fascial interposition.1 The vas occlusive technique that has been widely recommended in low resource settings, that is ligation of both the abdominal and testicular end of the vas with fascial interposition, is no longer recommended because of the reported high failure rates in one of the high quality studies.68 The AUA panel noted that the wide range of reported failure rates when ligation and fascial interposition are used for vas occlusion lead to an uncertain risk/benefit profile which is why it was not included in the recommended occlusion approaches, but also suggests that some providers consistently achieve good results with its use.1 Both the European Urology Association and the Canadian Urological Association are less specific than the AUA in terms of recommended occlusion methods, but both recommend the use of cautery or fascial interposition to reduce the risk of contraceptive failure.33, 77

Although occlusion approaches that require cautery may be more challenging to implement in resource limited settings, mucosal cauterization and fascial interposition have been successfully introduced in low resources settings particularly in Asia and Africa.45, 78

There is evidence that contraceptive failure is rare if 4 cm or more of the vas is removed, however extensive dissection is needed, which increases the risks of surgical complications. Additionally, removal of a large segment of the vas may make vasectomy reversal impossible.76 The risk of recanalization was not significantly associated with shorter segments excised in one study where 0.5–2.0 cm of vas segment were removed.79 Although most surgeons remove a segment of the vas, some investigators report success using division and occlusion of the vas without removal of any vas tissue itself.40, 80, 81, 82

Routine referral of the excised vas for pathologic study is neither essential nor recommended.1, 27, 83, 84, 85 The presence of two vas specimens does not substitute for determining the endpoint of azoospermia. Because the same vas may have been sectioned twice or a double vas may be present, the patient may still be fertile despite the fact that two separate specimens have been sent to the laboratory.84 Conversely, even if the laboratory cannot confirm the presence of vasa on microscopic examination, the patient may still have a successful procedure, because tissue can be distorted in removal or lost in transit to the laboratory.

Open-ended vasectomy (i.e. not sealing the testicular end of the cut vas) can be used with ligation, cautery or clips, and has been proposed as a way of increasing the likelihood of success if subsequent reversal is requested. The sperm granuloma that form on the end of the vas with open-ended vasectomy are thought to prevent pressure build-up and damage to the epididymis facilitating success of reversal.86 While there is some evidence to suggest that open-ended vasectomy may increase the success of vasectomy reversal,87 rigorous studies are lacking. Although published studies vary, it appears that open-ended vasectomy is not associated with increased failure when the prostatic end is adequate occluded.65 No firm conclusions can be made about the potential benefit of open-ended vasectomy in decreasing the risk of painful granuloma or epididymitis after vasectomy.65

POSTOPERATIVE CARE AND INSTRUCTIONS

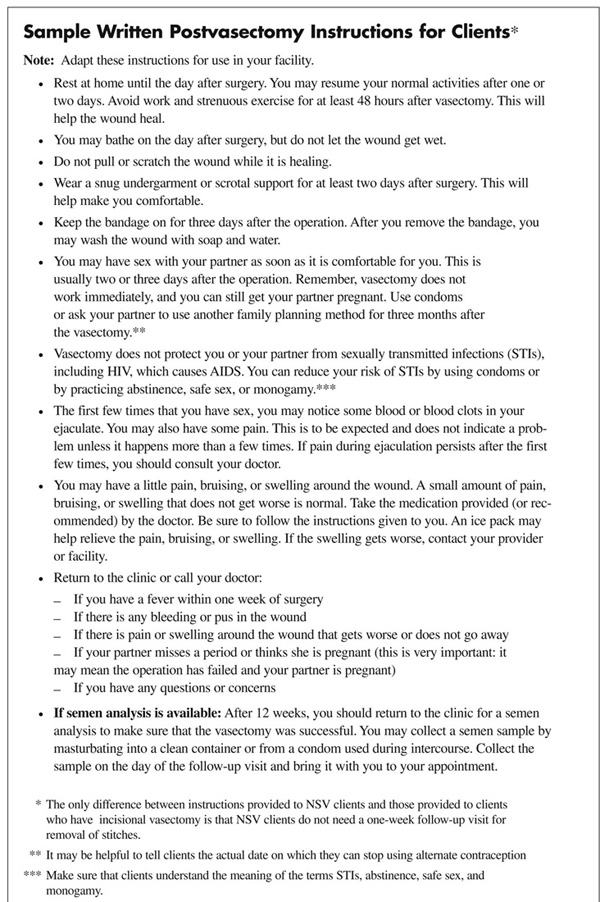

Men who have undergone vasectomy may leave the health facility after resting for 30 minutes. If the client has been sedated, his vital signs should be monitored every 15 minutes until stable; he then can be released. Information should be provided in simple language to the client regarding how to care for the wound, what side effects to expect, what to do if complications occur, where to go or who to call for emergency care, and where and when to return for a follow-up visit. He should also be informed of when he can resume normal activities including sex and the importance of using an alternative contraceptive method until azoospermia is established. Further, the client should be informed that minor pain and bruising are common and do not require medical attention. However, if he develops a fever, if blood or pus oozes from the vasectomy site, or if excessive pain, swelling, or bruising occurs, he should seek medical care. If the client can read, written postvasectomy instructions should be provided (Fig. 13). Use of mobile phone for follow up of clients after a vasectomy procedure has been successfully piloted and adopted by family planning programs.88

INTRAOPERATIVE AND IMMEDIATE COMPLICATIONS

Vasectomy is considered a minor and safe surgical procedure; complications are rare. Intraoperative complications may include vasovagal reaction and lidocaine toxicity. Table 4 provides information on management of intraoperative complications.

Table 4. Potential intraoperative complications of vasectomy (Adapted from no scalpel vasectomy curriculum - participant’s handbook; Engenderhealth 2007)

| Type of complication | Etiology | Symptoms/signs | Prevention | Treatment |

| Vasovagal reaction (neuro-cardiogenic syncope) | Painful procedure | Fainting | Use gentle surgical technique | Reassure the client |

| Lidocaine toxicity | Overdose of lidocaine | Numbness of tongue and mouth | Do not administer a dose >30 cc of 1% solution or >15 cc of 2% solution | Discontinue use of drug |

| Injury to testicular artery and/or other structures of the spermatic cord | Injury to blood vessels etc. during stripping of fascia from vas | Bleeding observed in fascia around the vas swelling as a result of the hematoma | Strip fascia and blood vessels carefully | Use cautery or ligation to control bleeding |

Immediate postoperative complications of vasectomy include bleeding, hematoma, and infection and in rare instances, drug related toxicity associated with problems in administration of the local anesthetic. Hematomas occur in approximately 2% of men; however, a wide range of rates have been reported, from less than 1% to nearly 30%.52 Studies consistently suggest that the incidence of hematoma is directly proportional to surgical skill and experience with the vasectomy procedure. In a large US-based survey among providers of conventional vasectomy (including urologists, family physicians, and general surgeons), the mean hematoma rate was significantly higher among physicians performing 1–10 vasectomies per year (4.6%) than among those performing 11–50 vasectomies per year (2.4%) or more than 50 vasectomies per year (1.6%).52 The corresponding incidences of hospitalization were 0.8%, 0.3%, and 0.2%, respectively.

Most infection related complications are minor, and an average incidence of 3.5% was reported in one series of more than 65,000 vasectomies.52 Several cases of gangrenous infection have also been reported in the past in Asia and Africa.41, 89 Higher rates of infection have also been reported.90, 91, 92 The incidence of infection has not been shown to vary by surgeon's experience.52

Rates of immediate complications also vary depending on the approach to the vas, with no-scalpel vasectomy consistently resulting in lower hematoma and infection rates than conventional vasectomy (see Table 3).

No association has been documented between use of general anesthesia or the setting where vasectomies were performed and any complication.52

Another early complication is sperm granuloma formation. Sperm that leak from the end of the cut vas may induce an inflammatory reaction leading to the formation of sperm granuloma. Sperm granulomas are seen in 15–40% of men presenting for vasectomy reversal.93, 94 Only approximately 2–3% of these are painful or in some way symptomatic; such symptoms peak at the second or third postoperative week.52, 93, 95 Discomfort can be treated symptomatically with anti-inflammatory drugs. Open-ended vasectomy has been reported to decrease the occurrence of sperm granulomas.82, 96, 97

In the immediate postoperative period, some pain may be expected as the local anesthetic wears off, however, this is usually short lived and responds well to non-steroidal analgesics and limiting of strenuous activities including sex during recovery. Pain in the postoperative period may also be caused by wound infection and should be evaluated if severe or persistent despite use of non-steroidal pain medications. Up to 30% of men report some type of pain 2–3 weeks after the vasectomy procedure.

Providers can prevent most complications by paying attention to hemostasis, practicing good aseptic technique, and minimizing tissue trauma during vasectomy procedures and wound care during the postoperative period. For example application of compressive dressing and scrotal elevation reduces the risks of developing hematomas.98 Table 5 provides information on prevention and treatment of complications of vasectomy.

Table 5. Potential postoperative complications of vasectomy

| Type of complication | Symptoms | Treatment | Prevention | Etiology |

| Bleeding

| Bleeding observed at incision site

| Most small vessel bleeding can be controlled by compression

| Careful surgical technique to separate vessels from the vas before transection

Use of techniques with lower chances of hematoma formation e.g. NSV | Provider 's failure to strip spermatic cord

|

| Hematoma

| Swelling of scrotum

| Control bleeding by pressure

Cautery and ligature may be used for large vessel bleeding

If hematoma is stable, allow to resolve on its own

Provide prophylactic antibiotics for 24 hours after vasectomy | Careful surgical technique

Understanding and carrying out of postvasectomy instructions regarding heavy lifting by client after vasectomy

| Rough handling of tissue

Provider’s failure to control bleeding before wound closure

Excessive strain or Client's failure to wear snug undergarments after vasectomy

Client's failure to rest

|

| Infection

| Pus, swelling, or pain at the incision site or in the scrotum

Fever

| Superficial infections: clean and apply local antiseptic and clean dressing Underlying tissue infection: antibiotics and wound care Abscess: antibiotics, drainage and wound care Cellulitis or fascitis: debridement, antibiotics, and wound care | Observance of proper infection prevention procedures

Recognition of bleeding

Client keeps wound dry after vasectomy

| Failure by provider to follow infection prevention procedures

Improper postoperative care of the wound

|

|

| ||||

| Sperm granuloma

| Pain at the testicular end of the vas or the tail of the epididymis

Nodule felt during palpation

| Asymptomatic: no intervention Pain: use nonsteroidal analgesics Persistent pain: evacuate the cyst; cut and seal the vas ¼ inch toward the testis Do not excise the granuloma Rarely, chronic pain warrants an epididymectomy | Unknown

| Occlusion of vas leads to accumulation of sperm

|

Major complications or mortality are extremely rare, although lethal complications can occur.99, 100, 101 The most comprehensive study of vasectomy-related mortality, based on over 400,000 vasectomies worldwide, found a mortality rate of 0.5 per 100,000 vasectomized men.101 Only 13 major complications were reported in a US survey of more than 65,000 vasectomies for a rate of 0.02%.52

SEMEN ANALYSIS AND CLEARANCE

Vasectomy success has routinely been confirmed by demonstrating the absence of sperm (i.e. azoospermia) in semen samples obtained at one or more clinic visits following the procedure. The time interval to the first follow-up visit is often between 6 and 12 weeks but may be as great as 4 months postvasectomy. In the past, some clinics scheduled follow-up based on the number of ejaculations following vasectomy, which may range from 15 to as many as 30 ejaculations prior to obtaining the first follow-up semen analysis.95, 102, 103, 104 Use of the number of ejaculations during the postoperative period is no longer recommended.1

There is little consistency in follow-up protocols in terms of when men are told to come for the first semen analysis or the number of azoospermic samples required before clearance is given.2, 83, 84 In a US-wide study of vasectomy providers, 74% suggested men return for semen analysis based on time since vasectomy, 18% based on number of ejaculations following vasectomy and the remaining 8% based on time and/or number of ejaculations following vasectomy.2 The recommended time or number of ejaculations since vasectomy for the semen analysis, as well as the number of azoospermic samples required before clearance, varied widely among those surveyed.2

This large degree of variability in clinical protocols for postvasectomy follow-up reflects the fact that good data regarding time and number of ejaculations to azoospermia following vasectomy are limited. Although there are more than one dozen published studies reporting on semen characteristics postvasectomy, well-designed clinical trials with serial follow-up visits are few.

A number of studies have reported the results of time or number of ejaculations to azoospermia following vasectomy.69, 71, 72, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112, 113 Follow-up protocols and procedures, definitions of azoospermia or success, and the way in which results are reported vary widely in these studies, and some reported results are conflicting. In addition, in some cases, important study details are lacking in the reports. All of these factors make interpretation or generalization of results and comparisons between studies difficult. For example, reported rates of azoospermia at 6 months range from 48% to 100%.69, 71, 72, 105, 106, 108, 111, 112, 114, 115, 116

Many of the current follow-up protocols require that men return for their first semen analysis at long intervals after vasectomy, and during this time an alternative method of contraception must be used. In addition, if azoospermia is not found at the initial visit, additional visits are necessary and in many cases even if azoospermia is found a confirmation visit is recommended. Compliance with postvasectomy follow-up has been shown to be poor, with 21–48% of men not returning for any follow-up, suggesting that the current follow-up protocols do not work very well.116, 117, 118, 119, 120, 121, 122, 123, 124, 125 Scheduling an appointment for follow-up at the time of the vasectomy was found to significantly improved compliance with both the initial visit and the recommendation for two consecutive azoospermic samples.126 In addition, there is growing support for granting clearance after one azoospermic semen analysis.83, 127, 128, 129

It is possible that azoospermia may not be the best endpoint for vasectomy, and indeed, achievement of azoospermia may not be necessary. As early as 1979 it was suggested that as long as no motile sperm were present, men could rely on their vasectomy for contraception without risk of pregnancy.130 There are now a number of reports indicating that non-motile sperm remaining after vasectomy are not associated with pregnancy.51, 109, 110, 130, 131, 132, 133 Suggesting that absence of motile sperm be the endpoint for vasectomy is not unreasonable given the fact that sperm motility is required for penetration of cervical mucus134 and for penetration of the oocyte.135 However, at least in the United States, concerns regarding malpractice in cases in which success has been declared without azoospermia and subsequent pregnancy occurs (even if due to recanalization) are likely to have affected decisions about follow-up recommendations. Nonetheless, various alternatives to azoospermia, at least in some cases, have been suggested including two consecutive counts of less than 10,000 sperm/ml with no motile sperm at least 7 months since vasectomy;51, 131, less than 10,000 non-motile sperm/ml in a fresh semen specimen at least 28 weeks after vasectomy;27 no motile sperm after 4 weeks,110, 12–18 weeks,112, 132 or greater than 18 weeks112 postvasectomy; and a single semen sample with less than 100,000 nonmotile sperm/ml at 3 months or more months after vasectomy.136

The latest AUA guidelines include the recommendation that clearance be given after examination of one uncentrifuged semen specimen shows azoospermia or only rare non-motile sperm, defined as ≤100,000 non-motile sperm/ml.1 The impact of this new definition of vasectomy success was explored by retrospectively applying the revised AUA criteria to nearly 1000 cases of vasectomy that had been performed before the new guidelines were released.137 Had the new guidelines been following in those cases, three repeat vasectomies for persistent rare nonmotile sperm and almost 900 additional semen analyses would have been avoided.

In resource-poor settings semen analysis may not be available or practical. In these settings it had been recommended that men wait 10–12 weeks or 15–20 ejaculations before beginning to rely on their vasectomy for contraception. Research suggests that telling men to use another form of contraception until 12 weeks after vasectomy is more reliable than 20 ejaculations69, 71, 72 and is now recommended to reduce the risk of pregnancy.138

EFFICACY

Overall, vasectomy is highly effective and one of the most reliable contraceptive methods available. Failure rates are commonly quoted to be between 0.1 and 0.4%, but failure rates reported in the literature show broader ranges, and rates as high as 1% to nearly 10% have been reported.139, 67, 68, 140, 141 The 2012 AUA vasectomy guidelines state that the pregnancy rate in partners of men who have documented azoospermia after vasectomy is about 1 in 2000.1 In general, vasectomy failure rates are considered to be similar to those for female sterilization, intrauterine devices and contraceptive implants.142 It is important to recognize the limitations of quoting exact failure rates for vasectomy. There are difficulties in interpreting the published studies on vasectomy efficacy because follow-up has been relatively short-term; most reports in the literature are retrospective reviews of individual physicians' experiences; definitions of failure, length of follow-up, and occlusion methods used vary among studies; and details on follow-up protocols, loss to follow-up rates, or statistical methods are often lacking.65 Large, well-designed, long-term studies that describe vasectomy failure rates have not been conducted.

Vasectomy failure may be due to user failure or to failure of the technique itself. User failure occurs when alternate contraception is not used during the period after vasectomy but before all sperm are cleared from the reproductive tract. One-quarter to one-half of pregnancies after vasectomy may occur during this time.68, 140, 143 The most common cause of failure of the vasectomy technique itself is spontaneous recanalization of the vas.104 This occurs when a sperm granuloma forms at the site of the vasectomy and links the two cut ends of the vas, creating passageways for sperm.144, 145 Recanalization can occur at any time after vasectomy and is frequently termed early or late. Early recanalization is characterized by a very low sperm concentration within a few weeks after vasectomy followed by return to large numbers of sperm. Many early recanalizations appear transient, eventually closing off and leading to successful vasectomy.146 Late recanalization occurs after azoospermia has been demonstrated, when motile sperm reappear in the ejaculate.51, 104 Late recanalizations can occur several years after successful vasectomy and are usually only identified when a pregnancy occurs; the actual rate in a large population has never been accurately determined. Other possible but rare causes of failure include occlusion of the wrong structure during the vasectomy procedure or the presence of an extra vas.104

REGRET

The vast majority of men who have a vasectomy do not regret their decision. Regret among men after vasectomy, most often reported as less than 5%, is lower than the reported regret among women after female sterilization.37, 39 Regret among women whose husbands had a vasectomy has been reported to be slightly higher than men's regret at 6–8%.147, 148 Studies have shown that regret among men is associated with marital instability at the time of vasectomy, young age (younger than 31 years), making the decision to have a vasectomy during a time of financial crisis or related to pregnancy, and having very young or no children at the time of vasectomy.37, 149, 150, 151 Regret is also often the result of client dissatisfaction with adverse health effects caused by or perceived to be caused by the procedure. Risk factors for regret should not be used by providers to restrict access to vasectomy for those in risk groups, but rather should be used to identify individuals who may need more extensive counseling. Satisfaction with pre-sterilization counselling has been found to correlate positively with post-sterilization satisfaction.34, 152

AREAS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

Results of potential new approaches for performing vasectomy are occasionally reported in the literature. For example, a pilot study examined the effectiveness of micro-curettes specially designed to strip the vas epithelium leading to scar formation and subsequent occlusion. Subjects achieved a sperm count of less than 200,000 sperm per ml by 3 months, however, subsequently semen analysis from 25% of the participants showed a dramatic increase in numbers of motile sperm reaching the lower limit of the normal level, indicating that further improvements in the approach are needed.153

Other vas deferens occlusion techniques that have shown promising results in animal studies involve the use of non-invasive laser vasectomy. Laser technology to achieve thermal coagulation of the vas deferens has been successfully demonstrated in canine vas deferens in vitro and in vivo studies of canine models without damage to skin and surrounding tissues including the spermatic cord.154, 155, 156

REFERENCES

Sharlip ID, Belker AM, Honig S, Labrecque M, Marmar JL, Ross LS, Sandlow JI, Sokal DC; American Urological Association. Vasectomy: AUA guideline.J Urol. 2012 Dec;188(6 Suppl):2482-91 |

|

Barone MA, Hutchinson PL, Johnson CH, et al: Vasectomy in the United States, 2002. The Journal of Urology 176: 232, 2006. |

|

United Nations (UN). 2012. World contraceptive use, 2011. New York: Population Division, Department of Economic and Social Affairs. |

|

Roy Jacobstein, John Pile: Vasectomy: the Unfinished Agenda: August, Acquire project working paper, 2007 |

|

Pile JM, Barone MA. 2009. Demographics of vasectomy USA and international. Urol Clin North Am. 36:295-305. |

|

Subramanian L, Cisek C, Kalanisis N, Pile JM: The Ghana vasectomy initiative facilitating client –provider communication on no scalpel vasectomy, Patient Educ Couns. 81(3)374-80, dol: 10.1016/j.pec. 2010.05.008. Epub 2010 |

|

Sheynkin Y. 2009. History of vasectomy. Urol Clin North Am. 36:285-294. |

|

International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and Macro International. 2007. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), 2005–06: India: Volume I. Mumbai: IIPS. |

|

Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) [Kenya], Ministry of Health (MOH) [Kenya], and ORC Macro. 2004. Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2003. Calverton, Maryland: CBS, MOH, and ORC Macro. |

|

National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) [Kenya] and ICF Macro. 2010. Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2008-09. Calverton, Maryland: KNBS and ICF Macro. |

|

Ghana Statistical Service (GSS), Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research (NMIMR), and ORC Macro. 2004. Ghana Demographic and Health Survey 2003. Calverton, Maryland: GSS, NMIMR, and ORC Macro. |

|

Ghana Statistical Service (GSS), Ghana Health Service (GHS), and ICF Macro. 2009. Ghana Demographic and Health Survey 2008. Accra, Ghana: GSS, GHS, and ICF Macro. |

|

National Population Commission (NPC) [Nigeria] and ORC Macro. 2004. Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2003. Calverton, Maryland: National Population Commission and ORC Macro. |

|

National Population Commission (NPC) [Nigeria] and ICF International. 2014. Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2013. Abuja, Nigeria, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: NPC and ICF International. |

|

National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) [Tanzania] and ORC Macro. 2005. Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey 2004-05. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: National Bureau of Statistics and ORC Macro. |

|

National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) [Tanzania] and ICF Macro. 2011. Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey 2010. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: NBS and ICF Macro. |

|

Department of Health, Medical Research Council, OrcMacro. 2007. South Africa. Demographic and Health Survey 2003. Pretoria: Department of Health. |

|

Institut National de la Statistique du Rwanda (INSR) and ORC Macro. 2006. Rwanda Demographic and Health Survey 2005. Calverton, Maryland, U.S.A.: INSR and ORC Macro. |

|

National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda (NISR) [Rwanda], Ministry of Health (MOH) [Rwanda], and ICF International. 2012. Rwanda Demographic and Health Survey 2010. Calverton, Maryland, USA: NISR, MOH, and ICF International. |

|

National Statistical Office (NSO) [Malawi], and ORC Macro. 2005. Malawi Demographic and Health Survey 2004. Calverton, Maryland: NSO and ORC Macro. |

|

National Statistical Office (NSO) and ICF Macro. 2011. Malawi Demographic and Health Survey 2010. Zomba, Malawi, and Calverton, Maryland, USA: NSO and ICF Macro. |

|

Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) and Macro International Inc. 2007. Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2006. Calverton, Maryland, USA: UBOS and Macro International Inc. |

|

Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) and ICF International Inc. 2012. Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2011. Kampala, Uganda: UBOS and Calverton, Maryland: ICF International Inc. |

|

Arwen Bunce, Greg Guest, Hannah Searing, Veronica Frajzyngier, Peter Riwa, Joseph Kanama and Isaac Achwal.: Factors Affecting Vasectomy acceptability in Tanzania, Internationa Family Planning Perspectives Vol. 33 number 1 March 2007 |

|

Philip Baba Adongo, Placide Tapsoba, James F Phillips, Philip Teg-Nefaah Tabong, Allison Stone, Emmanuel Kuffour, Selina F Esantsi2 and Patricia Akweongo.: “If you do vasectomy and come back here weak, I will divorce you”: a qualitative study of community perceptions about vasectomy in Southern Ghana. BMC International Health and Human Rights 2014 14:16. |

|

Noureen Nishtar, Neelofar Sami, Anum Faruqi, Shaneela Khowaja & Farid-Ul-Hasnain.: Myths and Fallacies about Male Contraceptive Methods: A Qualitative Study amongst Married Youth in Slums of Karachi, Pakistan Global Journal of Health Science; Vol. 5, No. 2; 2013 |

|

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Male and femal sterilsation. National evidence-based guidelines No. 4. London: RCOG Press, 2004. |

|

Lawrence Kincaid, Alice Payne Merritt, liza Nickolson, Sandra de Castro Buffington, Marcos Paulo P. de Castro, Bernadete Martin de Castro: Impact of a mass media vasectomy promotion campaign in Brazil, International Family Planning Perspective,22: 169-175, 1996 |

|

Nian C, Xiaozhang L, Xiaofang P, Qing Y, Minxiang L. Factors influencing the declining trend of vasectomy in Sichuan, China. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2010 Jul;41(4):1008-20. |

|

Eleigbe PN, Igberase GO, Eligbefoh J: Vasectomy: A survey of attitudes, counselling patterns and acceptance among Nigerian resident gynaecologists, Ghana Med J: 45(3):101-4 2011 Sep |

|

Grace Shih, Dube” Kate, Christine Dehlendorf: “We never thought of a vasectomy”: A Qualitative study on men and women’s counselling around sterilization: Contraception. 2013 Sep; 88(3):376-81. Dol:10.1016/j.contraception.2012.10.022 Epub 2012 Nov 21 |

|

Mumford SD: Vasectomy: The Decision-Making Process. San Francisco, San Francisco Press, 1977. |

|

Zini A. Canadian Urological Association Vasectomy update 2010. Can Urol Assoc J. Oct 2010; 4(5): 306–309. |

|

Pollack AE, Carignan C, Pati S: What's new with male sterilization: An update. Contemp Ob/Gyn 43: 41, 1998. |

|

Haws JM, Butta PG, Girvin S: A comprehensive and efficient process for counseling patients desiring sterilization. Nurse Pract 22: 52, 1997. |

|

Schwingl PJ, Guess HA: Safety and effectiveness of vasectomy. Fertil Steril. 2000 May;73(5):923-36. |

|

Shain RN: Psychosocial consequences of vasectomy in developed and developing countries. In Zatuchni GI et al (eds): Male Contraception: Advances and Future Prospects, pp. 34–53. Philadelphia, Harper & Row, 1986. |

|

Potts JM, Pasqualotto FF, Nelson D et al: Patient characteristics associated with vasectomy reversal. J Urol. 1999 Jun;161(6):1835-9. |

|

Holman CD, Wisniewski ZS, Semmens JB et al: Population-based outcomes after 28,246 in-hospital vasectomies and 1,902 vasovasostomies in Western Australia. BJU Int. 2000 Dec;86(9):1043-9. |

|

Davis LE, Stockton MD: No-scalpel vasectomy. Prim Care 24: 433, 1997. |

|

EngenderHealth. No-scalpel vasectomy curriculum: A training course for vasectomy providers and assistants: Participant handbook, 2nd ed. New York, EngenderHealth, 2007. |

|

World Health Organization (WHO): Improving Access to Quality Care in Family Planning: Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, Third Edition. Geneva, WHO, 2004. |

|

Li SQ, Goldstein M, Zhu J et al: The no-scalpel vasectomy. J Urol 145: 341, 1991. |

|

EngenderHealth. No-Scalpel Vasectomy: An Illustrated Guide for Surgeons, Third ed. New York, EngenderHealth, 2003. |

|

Labrecque M, Pile J, Sokal D et al: Vasectomy surgical techniques in South and South East Asia. BMC Urol. 2005 May 25;5:10. |

|

Grace Shih, Merlin Njoya, Marylène Lessard and Michel Labrecque Minimizing Pain During Vasectomy: The Mini-Needle Anesthetic Technique: J Urol. 2010 May; 183(5):1959-63. Epub 2010 Mar 19. |

|

Weiss RS, Li PS: No-needle jet anesthetic technique for no-scalpel vasectomy. J Urol. 2005 May;173(5):1677-80. |

|

White MA, Maatman TJ: Comparative analysis of effectiveness of two local anesthetic techniques in men. Urology. 2007 Dec;70(6):1187-9. |

|

Cook LA, Pun A, van Vliet H et al: Scalpel versus no-scalpel incision for vasectomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Apr 18;(2):CD004112. |

|

Michel Labrecque, Caroline Dufresne, Mark A Barone, Karine St-Hilaire: Vasectomy surgical techniques: A systematic review, BMC Med. 2004; 2: 21 |

|

Philp T, Guillebaud J, Budd D: Complications of vasectomy: Review of 16,000 patients. Br J Urol 56: 745, 1984. |

|

Kendrick JS, Gonzales B, Huber DH et al: Complications of vasectomies in the United States. J Family Pract 253: 245, 1987. |

|

Nirapathpongporn A, Huber DH, Krieger JN: No-scalpel vasectomy at the King's birthday vasectomy festival. Lancet 335: 894, 1990. |

|

Alderman PM: Complications in a series of 1224 vasectomies. J Fam Pract 33: 579, 1991. |

|