This chapter should be cited as follows:

Kihara AB, Koigi PK, Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.417943

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Gynecology Module

Volume 1

Female genital mutilation

Volume Editor:

Professor Anne-Beatrice Kihara, University of Nairobi, Kenya,

President-elect. The International Federation of Gynecology and Obestetrics FIGO

President, African Federation of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (AFOG)

Chapter

Social and Gender Norms and the Bio-Ecological Modeling Influencing the Practice of Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (FGM/C)

First published: July 2022

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

INTRODUCTION

The practice of female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) is considered a form of abuse that undermines girls’ and women’s dignity and violates their human rights.1 Sexual and reproductive health (SRH) affects, and is affected by the intersectionality of people’s personal experiences and relationships and by the broader structural context of their lives, which shapes their overall health and well-being. This context includes gender inequality as a determinant on its own and in combination with other social and economic inequalities including the following: unequal power dynamics in interpersonal relationships, harmful gender and other socio-cultural norms and practices, limited economic circumstances, lack of access to education, limited employment opportunities, poor living conditions, disability, ethnicity, as well as the challenging political and legal environments where they live.

It has been demonstrated that harmful gender norms that promote male dominance over women prevent women from practicing safer sex, limit their use of contraceptives, and increase their risk of STIs, including HIV and gender-based violence.2 Similarly, research has also shown a relationship between violation and neglect of human rights and negative health outcomes.

FGM/C IN THE SOCIAL CONTEXT

FGM/C includes all procedures involving partial or total removal of the female external genitalia or other injuries for non-medical reasons.3 The World Health Organization (WHO) has developed a clear typology of FGM/C to include the following: clitoridectomy (type I); excision (type II); infibulation (type III); and all other harmful procedures to the female genitalia for non-medical purposes (type IV). The practice has undergone considerable changes (shifts) in form and context shaped by both social and gender norms. Factors that enhance perpetuation of the practice include the following: that there are societies where its socially acceptable; it is thought to affirm fidelity; marriageability; manifestation of cleanliness and health; it is thought to prevent rape; provides income for circumcisers; and perceived esthetic appeal. Interventions are increasingly taking on a more holistic approach, including the healthcare and justice systems. Within the social sphere, interventions have evolved rapidly to include the following: policy directives; large-scale campaigns; education programs; skills building; and economic empowerment programming; community mobilization; participatory group education; awareness and capacity building; training; and service delivery in human rights. Such interventions aim to transform the social milieu using a trident approach, viz., to change the underlying attitudes and norms that support violence against women and girls related to FGM/C; empowering women and girls economically and socially; as well as promoting nonviolent, gender-equitable behaviors.4,5,6

SOCIAL NORMS AND GENDER NORMS IN RELATION TO FGM/C

Social norms are integral to FGM/C, child marriage, and intimate partner violence. Harnessing insights from social norms' theory to catalyze change around gender inequity and harmful gender-related practices requires an in-depth understanding of indigenous knowledge systems; monitoring of the epidemiology associated with harmful practices; knowledge on gender theory and re-framing with alternative strategies and programmatic approaches that negotiate for new norms that dismantle harmful gender-related practices. Agency, power, norms, and values can be aligned or even exert opposite influences on people’s actions. It behooves therefore value clarification and attitude transformation stream in tandem with theories for change to culminate in transformative behaviors that are sustainable. Communication strategy is crucial to avert the “boomerang effect” with campaigns that emphasize the widespread prevalence of a harmful practice. The importance of “cultural-embeddedness” and engaging community members as leaders of the change process. In FGM/C, the social norms tend to be fraught with an idiosyncratic admixture of uncertainty, identity, reward, and enforcement.

Social norms are behavioral rules shared by people in a given society or group; they define what is considered “normal” and appropriate behavior for that group. Social norms influence what people do both in familiar situations (because they know the rules, descriptive norm) and in unfamiliar ones (because they do their best to learn the new rules and comply with them, injunctive norm). This is associated with a social reward or punishment, respectively.

Gender norms are both a source and a reinforcer of inequality between men and women.

Gender norms are social norms that specifically define what is expected of a woman and a man in a given group or society. They shape acceptable, appropriate, and obligatory actions for women and men (in that group or society), to the point that they become a profound part of people’s sense of self. They are both embedded in institutions and nested in people’s minds. They play a role in shaping women’s and men’s (often unequal) access to resources and freedoms, thus affecting women’s and men’s voice, agency, power, and performance.

There are differences between social and gender norms. Social norms are cross-disciplinary and include, amongst others, the following: sociology, anthropology, human science, philosophy, legal, and communication. They have an individual of collective social construct; can be sociable or moralistic; interdependent or independent; discordant norms and attitude or concordant norms and attitude; harmful or protective practices7 driving attitudes and behaviors. Norms can provide value – neutral information such as following the crowd, benchmarking with points of reference, efficient course of action, and having a common communication language. Norms can create external influencers such as role models, social pressure that can be enforced positively or negatively or can be anticipatory of rewards or punishment. Norms can be influenced internally based on innate values and preferences. Norms can evolve through a life cycle recognized as emergent if it is created, innovated, or ideated. Norms can be processed to become recognized and accepted with sub-stages of norm acquisition, assimilation, acceptance, learning, and socially learnt with adoption. Norms emerge in a group by spreading, transmission, and diffusion. Norms' establishment in society or in individuals is through stabilization and crystallization, institutionalization and internalization. Norms exist but are relevant in certain circumstances known by norm activation or their detection. Long-term persistence of a norm occurs through cultural continuity and stability. When norms change from their original form, they have undergone creative mutation. Norms either gain or decline in significance as they are either cascaded or diminished, respectively. When norms disappear, they are obsoleted. In addressing the FGM/C life cycle of norms and the various sub-stages, the norm target, drivers, beneficiaries, and victims need to be identified.8 It is therefore vital to comprehend the social context when planning, designing, and implementing programs and interventions.

Gender norms provide other influencing factors such as the following: the role of power in structuring social relations; the role of childhood socialization practices in social learning; and the recognition that norms can be embedded in institutions and gender as "performance".9 Descriptive norms tend to be risk averse; Injunctive norms are oppositive in nature and tend towards formation of strategic alliances; and there are also Innate personal norms that are intrinsic to an individual. Effective change requires changing descriptive, injunctive, and personal norms. While strategies exist for changing the first two, less is available in the norms' literature about how to change behaviors motivated by rituals that are sacred and traditional. Rituals can be reconstructed with the help of traditional and/or religious authorities, preserving the sacred dimensions of the shared values.10 Change in society necessitates testing interventions that integrate norms within a wider framework. Therefore, successful social change interventions should intuitively integrate the symbiosis amongst norms, agency, and values, and possibly address them in the wider ecological context.

THE BIO-ECOLOGICAL MODEL

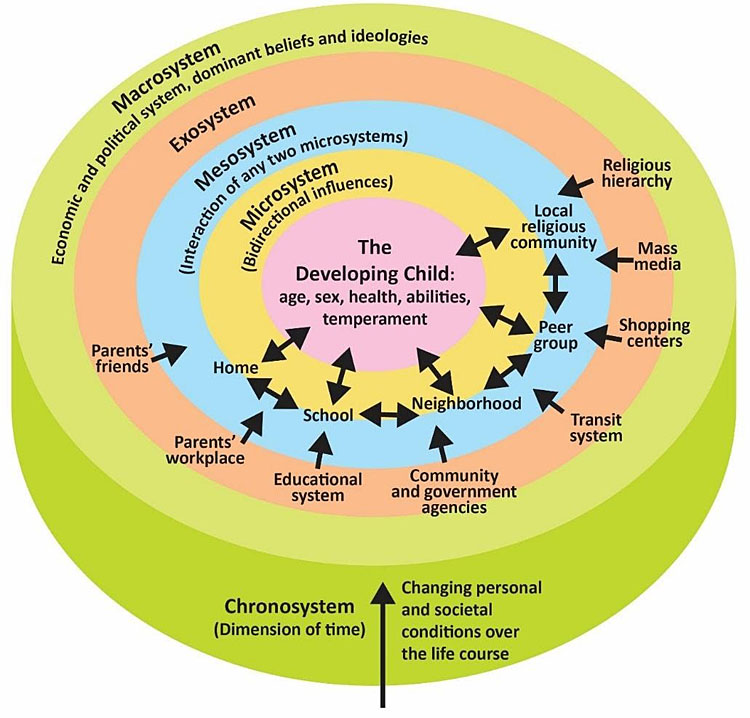

The bio-ecological model was developed by Bronfenbrenner and is illustrated in Figure 1. It highlights the patterns of development across time within the context of the interactions between the development of the child and the influencing environment.

1

Bronfenbrenner's theory of ecological systems.11 Reproduced under Creative Commons license.

The various components of Bronfenbrenner’s bio-ecological model include the following:

- Microsystem: Microsystems impact a child directly. These are the people with whom the child interacts such as parents, peers, and teachers. The relationship between individuals and those around them needs to be considered.

- Mesosystem: Mesosystems are interactions between the microsystems surrounding the individual. The relationship between parents and schools, for example, will indirectly affect the child.

- Exosystem: Larger institutions such as the mass media or the healthcare system are referred to as the exosystem. These have an impact on families and peers and schools who operate under policies and regulations found in these institutions.

- Macrosystem: We find cultural values and beliefs at the level of macrosystems. These larger ideals and expectations inform institutions that will ultimately impact the individual.

- Chronosystem: All of this happens in a historical context referred to as the chronosystem. Cultural values change over time, as do policies, legislature, and regulation of institutions or governments in certain political climates. Development occurs at a point in time.

Various studies have shown norm changes are not linear and influenced by the ecological environment; shaming; group dynamics, incentives12 and the context. Other studies found correlations between cultural tightness, social order, and openness.13,14 Examples include the grandmother project-change through culture;15 the medicalization of FGM/C thought to emanate in some communities from conformity to culture/tradition, religion, marriageability, fear of negative sanctions, as a rite of passage and with less complications and legal ramifications.16 These factors all imply that interventional designs need to be responsive to these challenges and their related implications. Often deviant norms break the tightest compliance offering for change. Some examples include the following: engagement and mobilization of communities for ownership and as leaders of the processes integrating science and traditional positive practices such as alternative rites of passage; witnessing of events such as campaigns, including the impact of the African Union Continental Initiative (Saleema) in Sudan17 and the power of disapproval of the FGM/C acts like the Prohibition of Female Genital Mutilation Act in Kenya.18

CHANGING SOCIAL NORMS VISIBLY

The learning community with social and gender norms need to do as follows:

- Advance the science through strengthening the measurement of social and gender norms.

- Provide for a common language and concepts by developing and sharing practical theoretical tools to advance clarity and congruence in the design, monitoring, and evaluation of normative interventions.

- Strengthen the planning, design, implementation, evaluation, and costing related to wards elimination of harmful practices through normative change interventions going to scale.

Steps for social norm change

The four core steps that result in social norm change includes the creation of a core group of participants in the intervention to renegotiate norms among themselves and develop skills to motivate others outside of the group. The second step is sustained values' deliberations, where participants discuss within the group the common values that underlie their support for a practice (e.g., love for our daughters underlies female genital cutting). Differentiating between values and practices ensures that participants do not resist the discussions around changing the practice, reassured that they are deliberating around the best ways to embody their common values. The third step is the organized diffusion of knowledge: first from participants to other community members and next to other surrounding communities. The fourth and final step is the coordinated shift to new practices, sealed by public events where community members commit to the new practice.19,20,21 Unfortunately, often the emerging community of social norm change practitioners is fragmented, lacking theoretical clarity and validated measures, and has poorly documented the scale-up processes of social norm interventions. Advocacy needs to be sustained and replicable with documentation of processes and reporting of outcomes harvested.22

Changing gender norms

Gender norms succeed where culture is treated as being and building on what exists. Gendered norms are embedded in social structures, operating to restrict the rights, opportunities, and capabilities, of women and girls, causing significant burdens, discrimination, subordination, and exploitation. FGM/C is an indicator of gender inequality and inequity. It is further linked to child marriage, forced sexual debut, and health complications across the life course. There is need to strengthen internal assets such as increasing knowledge, self-efficacy, and providing basic resources. Encouraging reflection critically on inequitable gender norms and roles. Harnessing socialization processes to form and transform gender norms and roles. Engaging men in sexual and reproductive health and rights outcomes, strengthening social networks and mobilizing economic and social support at key turning points. Empowering girls/women is key to them advocating for themselves and strengthening their ability to seek help and resist paths imposed upon them. Addressing structural issues such as girls’ education and access to resources and decision-making; and mobilizing communities to create enabling environments.23 This can have a positive impact on gender relations, sexual and reproductive health choices, and health-related behavior, thus accelerating progress in elimination and abandonment of the FGM/C practice.24,25,26

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- Sexual and reproductive health affects and is affected by the intersectionality of people’s personal experiences, relationships, and the broader social contexts of their lives.

- Although various societies have differing gender norms, they share the common denominator of the fact that male dominance over women enhances the frequency, severity, and acceptability of violation of women’s human rights.

- Despite rapidly evolving social, legal, and policy interventions, Female genital mutilation/cutting remains highly prevalent in the societies where it is a norm.

- Understanding the bio-ecological context of female genital mutilation/cutting victims enhances the ability to design, develop, and implement effective changes by modifying descriptive, injunctive, and innate personal norms.

- Encourage modification of adverse gender norms to enhance equality and equity would improve gender relations, sexual and reproductive health choices and health-related behavior would accelerate progress in cultural abandonment of female genital mutilation/cutting.

- Evaluate patients using the bio-ecological model. This will enhance understanding of the victim’s context and is highly likely to facilitate protection of others within her circles that are at risk of undergoing the procedure.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) of this chapter declare that they have no interests that conflict with the contents of the chapter.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

REFERENCES

World Health Organization. Eliminating female genital mutilation: An interagency statement, 2008. http://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/eliminating_fgm.pdf (accessed on 30/9/2021). | |

Utz-Billing I, Kentenich H. Female genital mutilation: an injury, physical and mental harm. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynecology 2008;29(4):225–9. | |

World Health Organization. WHO guidelines on the management of health complications from female genital mutilation 2016. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/206437/1/9789241549646_eng.pdf?ua=1. | |

Heise LL. What works to prevent partner violence? An evidence overview. STRIVE Research Consortium, ESRC, UKAID & LHSTM working paper 2011:1–108. ISBN: 978-0-902657-852. | |

Morrison A, Ellsberg M, Bott S. “Addressing gender-based violence: A critical review of interventions”. World Bank Research Observer 2007;22(1):25–51. | |

Keleher H, Franklin L. Changing gendered norms about women and girls at the level of household and community: a review of the evidence. Global Public Health 2008;3(Suppl 1):42–57. DOI: 10.1080/17441690801892307. | |

Cislaghi B. Theory and Practice of Social Norms Interventions: Eight Common Pitfalls. Global Health 2018;14:83. Available at https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-018-0398-x. | |

Legros S, Cislaghi B. Mapping the Social-Norms Literature: An Overview of Reviews. Perspect Psychol Sci 2020;15(1):62–80. doi: 10.1177/1745691619866455. | |

Fenstermaker S, West C, Zimmerman D. Gender inequality: New conceptual terrain. Doing Gender, Doing Difference 2002:25–39. | |

Morris M, Hong Y, Chiu C, et al. Normology: Integrating insights about social norms to understand cultural dynamics. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 2015;129:1–13. | |

Theories Developed for Understanding the Family 2021. Retrieved September 29, 2021, from https://socialsci.libretexts.org/@go/page/39213. | |

Sen G, Ostlin P, George A. Unequal unfair ineffective and inefficient. Gender inequity in health: Why it exists and how we can change it. Final report to the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health. 2007. | |

Harrington JR, Gelfand MJ. Tightness–looseness across the 50 united states. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2014;111(22):7990–5. | |

Gelfand MJ, Nishii LH, Raver JL. On the nature and importance of cultural tightness-looseness. Journal of Applied Psychology 2006;91(6):1225. | |

Passage Project – Grandmother Project: Change through Culture. Girls holistic development USAID IRH 2020 https://irh.org/resource-library/ghd-quant-report/ (Accessed on 30/9/2020, 11.00 am). | |

Kimani S, Kabiru CW, Muteshi J, et al. Female genital mutilation/cutting: Emerging factors sustaining medicalization related changes in selected Kenyan communities. PLoS One 2020;15(3):e0228410. Published 2020 Mar 2. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0228410. | |

African Union Press Release. The African Union launches a continental initiative to end female genital mutilation and save 50 million girls at risk. Union Africane (online) 2019. Accessed from https://au.int/fr/node/35892 on 27th December at 4:10 pm. | |

Government of Kenya. Prohibition of Female Genital Mutilation Act No. 32 of 2011. National Council for Law Reporting 2011:1–14. Accessed from http://kenyalaw.org on 27th December, 2021 at 3:09 pm. | |

Cislaghi B, Gillespie D, Mackie G. Values Deliberation and Collective Action: Community Empowerment in Rural Senegal. New York: Palgrave, 2016. | |

Keizer K, Lindenberg S, Steg L. The spreading of disorder. Science 2008;322(5908):1681–5. | |

Keizer K, Lindenberg S, Steg L. The importance of demonstratively restoring order. PLoS One 2013;8(6):e65137. | |

USAID. Towards shared meaning: A challenge paper on social and behavioural change and social norms 2021 https://irh.org/resource-library/challenge-paper/ (Accessed on 30/9/2021 at 11.10am). | |

Passage project Study of the Effects of the Husbands’ School Intervention on Gender Dynamics to Improve Reproductive Health in Niger 2021 https://irh.org/resource-library/husbands-school-niger/ (cited 30/9/2021 11.19am). | |

Battle J, Hennink M, Yount K. Influence of female genital cutting on sexual experience in Southern Ethiopia. Int J Sex Health. 2017;29:173–86:79–94 | |

Fulu E, Miedema S, Roselli T, et al. Pathways between childhood trauma, intimate partner violence, and harsh parenting: Findings from the UN multi-country study on men and violence in Asia and the Pacific. Lancet Global Health 2017;5:e512–e522 | |

Farage M, Miller K, Tzeghai G, et al. Female genital cutting: Confronting cultural challenges and health complications across the lifespan. Women’s Health 2015;11:79–94. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards programme CLICK HERE)