This chapter should be cited as follows:

Lemmon B, Pereira S, Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.414003

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Obstetrics Module

Volume 11

Labor and delivery

Volume Editor: Dr Edwin Chandraharan, Director Global Academy of Medical Education and Training, London, UK

Chapter

Delivery of Twins

First published: February 2021

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

INTRODUCTION

Worldwide 2–3% of all live births are multiples,1 the majority of these (97%) being twins.2 The incidence of twin pregnancies is increasing due to the use of fertility drugs and advancing maternal age at time of pregnancy observed in well-resourced countries. It is known that with a maternal age of over 35 there is an increased rate of twinning,3 and up to 24% of successful IVF cycles end in a multiple pregnancy.1 This is significant as both maternal and perinatal mortality and morbidity is higher in twin compared to singleton pregnancies4 (Tables 1 and 2). Twin pregnancies are more likely to be complicated and so require more intensive antenatal monitoring as well as specialized intrapartum care. Ideally the care of a twin pregnancy should be by a multidisciplinary team with experience of these pregnancies. This chapter focuses on recommendations for the care of women with a twin pregnancy in labor and at delivery.

Singleton | Twins | |

Pre-eclampsia | 2.3% | 8.1% |

Gestational diabetes | 2.3% | 4% |

Hemorrhage | 1–3% | 25% |

Risk of emergency cesarean section | 25% | 40% |

Singleton | Twins | |

Fetal anomaly | 2.4% | DC: 3.2% MC: 5.5% |

Small for gestational age | 10% | 47% (at least 1 baby <10th centile growth) |

Preterm birth | <37 weeks: 7% <34 weeks: 1% | <37 weeks: 57% <34 weeks: 20% <32 weeks: 10% |

Neonatal death per 1000 (2016) | 1.6 | 5.3 |

DC, dichorionic; MC, monochorionic.

TYPES OF TWINS DEFINED BY TYPE OF PLACENTATION AND AMNIONICITY

Dichorionic diamniotic twins

Dichorionic diamniotic twins (DCDA: two placentas, two amniotic sacs) account for approximately 80% of all twins and this includes 10% of twins resulting from monozygotic conceptions (same zygote which divides early enough to produce two separate placentas). In DCDA twins each baby has its own placenta (separate or confluent), and its own amniotic sac. They tend to run in families and seem to have a particularly high prevalence in women from West African descent. The incidence of DCDA twins is increasing globally, largely due to the use of ART (artificial reproductive technologies) with more than one embryo being transferred and the use of ovulatory drugs for fertility treatment.1

Monochorionic twins

Monochorionic twins (one placenta) make up the remaining 20% of twin pregnancies. All monochorionic twins result from the fertilization of a single ovum and therefore are monozygotic, sharing the same genetic background and being also of the same gender (identical twins). Of monochorionic twins, 99% are diamniotic therefore share a placenta but have separate amniotic sacs (MCDA), and 1% are monoamniotic (MCMA) sharing the same placenta and amniotic sac. The rate of monochorionic twinning remains stable at three in 1000 deliveries worldwide.10

Due to their shared placenta, monochorionic twins are at higher risk of in utero complications antenatally. This includes the risk of twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS) and fetal growth restriction (FGR) of one or both babies. Severe TTTS occurs in about 15% of MCDA twins. It is most likely to happen between 16 and 24 weeks, but can occur at any point in gestation, including intrapartum. In TTTS there is a hemodynamic imbalance in blood flow across the placental anastomoses resulting in one twin being volume overloaded and the other depleted. Selective growth restriction affects approximately 15% of otherwise uncomplicated of MC (monochorionic) pregnancies, but >50% of MC pregnancies with TTTS. MC pregnancies can also be affected by twin-anemia-polycythemia sequence (TAPS), where small arterio–venous anastomoses allow blood to flow from a donor twin to a recipient. This occurs in up to 13% of pregnancies following laser treatment performed for TTTS. A rarer consequence of MC pregnancy is twin reversed arterial perfusion (TRAP) sequence, where one of the twins is “acardiac” meaning that the twin with a working heart pumps blood around both twins. This occurs in only 2.5% of MC pregnancies with only the one twin with a heart being viable.

MODE AND TIME OF DELIVERY

When deciding on the most appropriate mode of delivery in a twin pregnancy, several factors need to be considered including presentation of the first twin, gestational age, fetal well-being (has the pregnancy been complicated by FGR or TTTS for instance) and chorionicity. The plan for delivery, whether it is an elective cesarean section or a planned vaginal delivery, should be made together with the woman and her partner antenatally where possible.

The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommend uncomplicated MCDA twins to be delivered between 36 and 37 weeks and DCDA twins to be delivered between 37 and 38 weeks.11,12 There is also some additional evidence which suggests that offering planned delivery at 37 weeks for uncomplicated DCDA twins, and 36 weeks for uncomplicated MCDA twins helps reduce the risk of stillbirth.13

The Twin Birth Study14 has shown that in pregnancies between 32 and 38 weeks where the presenting twin is cephalic, a planned cesarean section does not reduce fetal or neonatal morbidity or mortality, irrespective of chorionicity or lie of twin two. This means that uncomplicated MCDA and DCDA twins with a cephalic presenting twin can be offered vaginal delivery.15 It is important when counseling women not to allow personal opinions to sway her decision.

There is no firm evidence to clearly show that planned cesarean section or planned vaginal delivery is better for either the woman or her twins.16 The decision regarding the mode of delivery should be made considering the balance of risks and benefits for that individual woman’s circumstances. Involvement of healthcare professionals with experience in delivering twins can aid in this discussion. A cephalic presenting baby who is much smaller than the second twin may pose an increased risk of complications in the second stage. Conversely, a breech presenting twin with a woman progressing well in labor may be considered to continue with a vaginal delivery (Table 3).

3

When to deliver twins?

Gestational age (weeks) | |

Dichorionic diamniotic | 37–38 |

Monochorionic diamniotic | 36–37 |

Monochorionic monoamniotic | 32–33 |

There are certain situations where delivery by cesarean section is advised. In MCMA twins, for example, delivery by cesarean section between 32 and 33+6 weeks' gestation is recommended due to the high risk of cord entanglement and resultant stillbirth. Retrospective data have shown that the risk fetal death in monoamniotic twin pregnancies is greater than the risks of prematurity (non-respiratory issues in particular) at 32 weeks' gestation. The data have also shown that outcomes for these babies are the same whether the mother is admitted as an inpatient or there is extensive outpatient surveillance.17 Delivery by cesarean is also advised for conjoined twins to avoid obstructed labor, and in twins where the presenting twin is non-cephalic.

Indications for delivery by cesarean section

- Monochorionic monoamniotic twins

- Triplets and higher number multiples

- Conjoined twins

- Presenting twin not in cephalic presentation

- Twins complicated by TTTS/TAPS/FGR

FIRST STAGE OF LABOR

When a pregnant woman with a twin pregnancy presents in labor there are some additional preparations to be made. Twin deliveries are more likely to require obstetric, anesthetic and neonatal expertise as they are associated with a higher rate of dystocia, assisted delivery and postpartum hemorrhage.

Start by reviewing any antenatal complications, assessing maternal and fetal well-being and determining presentation of the first twin. If possible, the use of a bedside ultrasound scan to establish presentation and lie of second twin is also important. Informing and involving team members including the anesthetist and neonatologist is crucial in addition to preparing equipment needed to welcome two babies. When available, continuous fetal heart rate monitoring is recommended. It is especially important to exclude that only one baby is being monitored with the same trace repeated twice. Oxytocin can be used for augmentation as per singleton guidelines. IV access is recommended in view of the increased risk of postpartum hemorrhage.

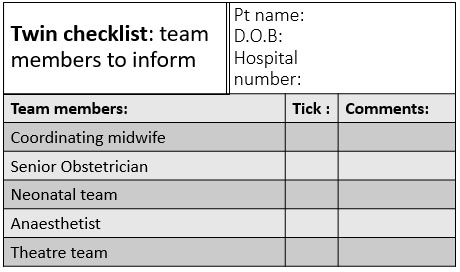

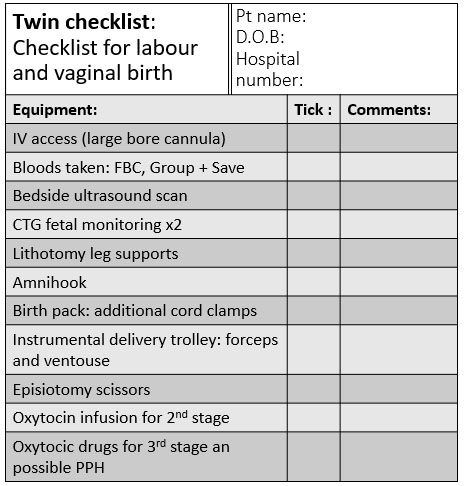

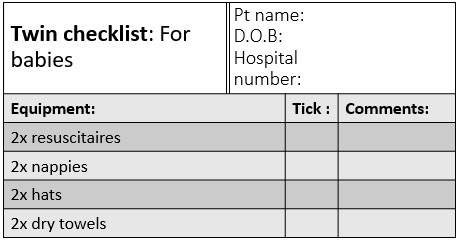

Below are examples of checklists that could be used when a woman with a twin pregnancy is admitted to the delivery suite (Figure 1). The final delivery plan should be discussed with the woman and her partner following the initial evaluation, the team members are introduced and a suitable space for delivery is found. There is considerably more equipment required than for a singleton delivery and, therefore, having an appropriately sized room or having the delivery in theater can be considered.

1

Examples of checklists that could be used when a woman with a twin pregnancy is admitted to the delivery suite.

SECOND STAGE OF LABOR: DELIVERY

In the second stage, all equipment should be already set up and checked in the labor room. Delivery of the presenting twin is the same as delivering any singleton pregnancy. The only difference is that both babies should be actively monitored. If there are any concerns about hypoxia in the second twin, then delivery of both babies should be expedited. Vaginal delivery of twins involves three stages: delivery of first twin, inter-delivery time interval and delivery of second twin.

It is widely appreciated that the time after the delivery of the presenting baby is of high risk for the second twin. Studies have shown a gradual drop in umbilical cord pH with increasing interdelivery time interval.18 Long interdelivery time intervals have been shown to be related to lower Apgar scores at delivery and an increased risk of hypoxia.19 As this is a high-risk period, ensuring that there is adequate fetal monitoring of twin two is essential. Having experienced team members present is likely to help make good clinical judgments regarding active management. Some considerations should include optimizing contractions with oxytocin infusion and stabilizing a longitudinal lie in twin two prior to performing an ARM (artificial rupture of membranes). There is a balance between early over-intervention with a ARM performed too soon and an increased risk of cord prolapse, and under-intervention leading to a long intertwin delivery interval.

Delivery of twin one

The same as delivering a singleton baby. It is advisable to clamp and cut the cord immediately for monochorionic twins to reduce the theoretical risk of twin-to-twin transfusion of blood at birth. The benefits of delayed cord clamping that have been shown in singletons have not been shown in twins. It is good to use different clamps for each baby to help differentiate between cords if paired blood samples are needed.

For delivery of the first twin, an episiotomy may have been performed and there may be vaginal trauma. It is important not to neglect the on-going blood loss from tissue trauma. Examination of the perineum with a clamp or sutures placed to bleeding vessels may help reduce the risk of postpartum hemorrhage.

Interdelivery interval

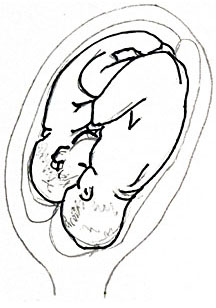

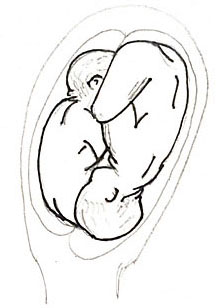

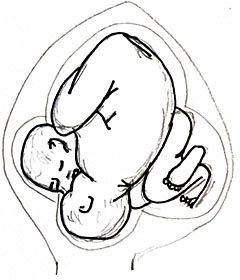

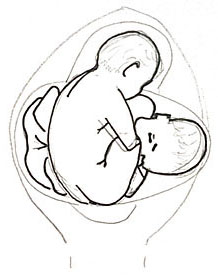

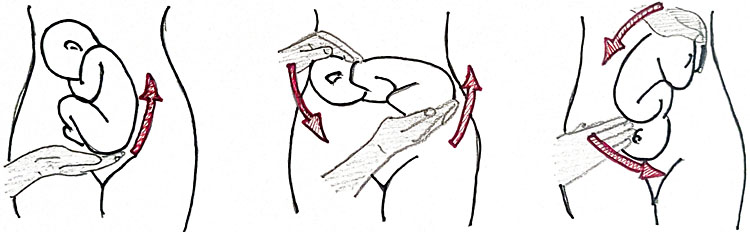

This is the time between delivery of the first and second baby. After the first baby is delivered an assistant is needed to stabilize the second baby, so it adopts a longitudinal lie – either cephalic or breech (see Figure 2). Confirmation of the presenting part for second twin can be done by performing vaginal examination or using a bedside ultrasound scanner if available. It is important to keep the membranes of the second twin intact whilst confirming the lie as rupturing them at this point can result in cord prolapse. If the second twin is not in a longitudinal lie, intact membranes will also aid maneuvers. There are two acceptable techniques for guiding the second twin into a longitudinal lie:

- ECV: external cephalic version. Involves using hands externally on the abdomen to encourage the baby to “roll” into a longitudinal position (Figure 3).

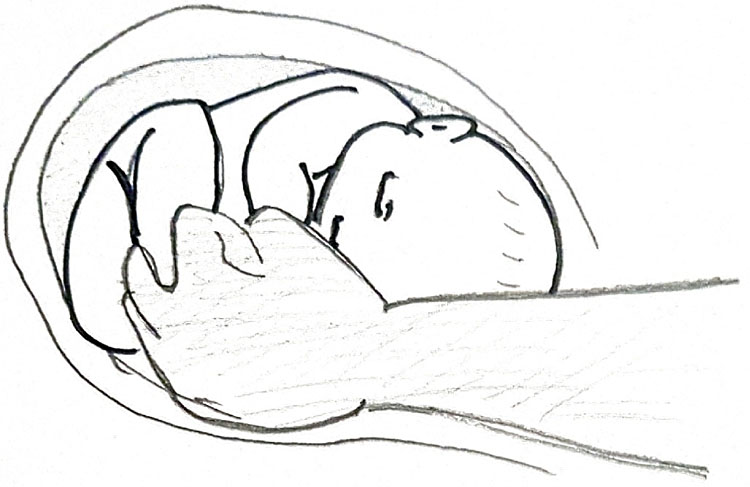

- IPV: internal podalic version. A vaginal examination is performed and one or both feet are identified (with membranes intact if possible), the feet are grasped to perform a breech extraction (Figure 4). IPV has been shown to lower risk of cesarean section compared to ECV without there being increased risk of harm.

Once there is a longitudinal lie achieved, it is important to keep the hands on the maternal abdomen stabilizing the fetal lie until uterine activity re-starts to avoid the baby returning to a transverse position. It is usual for the uterine contractions to become less frequent and hypotonic after delivery of the first baby. Only once a longitudinal lie (cephalic or breech) is achieved, oxytocin infusion (prepared and ready in the room) to help augment uterine activity should commence. Rupture of membranes should be avoided until the presenting part of the second baby is in the pelvis. ARM too early can also result in cord prolapse. The second twin should be monitored continuously.

|

|

|

cephalic–cephalic | cephalic–breech | breech–breech |

|

|

|

cephalic–transverse | breech–transverse | transverse–transverse |

2

Cephalic or breech.

3

External cephalic version (ECV).

4

Internal podalic version (IPV).

Delivery of second twin

If twin two is not showing signs of hypoxia on fetal monitoring then delivery can be managed expectantly with oxytocin infusion to optimize contractions if needed. Intervention with an assisted delivery is indicated if there are concerns about fetal well-being or there is delay in delivery of the second twin despite maternal expulsive effort.

THIRD STAGE OF LABOR

The third stage of labor in twin pregnancies should also be monitored and managed actively. This is because of the greater chance of significant hemorrhage. The postpartum hemorrhage rate in twin deliveries is quoted to be as high as 25%.20 This is likely secondary to overdistension of the uterus and the subsequent higher incidence of hypotonic contractile strength after delivery. Active management of the third stage of labor involves clamping and cutting the cords, giving an oxytocic agent (oxytocin, ergometrine or combination) and controlled traction placed on the cords to deliver the placental mass early. It has been shown that in singleton pregnancies active management of the third stage reduces blood loss at delivery21 and, therefore, it is widely accepted active management should be used routinely for twin deliveries.

CESAREAN SECTION FOR TWINS

Deciding to deliver by planned cesarean section should be a decision made between a senior obstetrician with the pregnant woman and her partner. There is a consensus that an elective cesarean should be recommended if the presenting twin is non-vertex. This is probably inferred from evidence in studies looking at outcome from singleton breech presenting babies and mode of delivery.22

Even when the mode of delivery planned is a vaginal birth there is a 30–40% risk of requiring an emergency cesarean in labor in twin pregnancies.23 This is due to fetal distress of either twin, dystocia of labor or signs of infection (the same as for singleton pregnancies). Even once the delivery of the presenting twin has been completed, there remains a risk of needing to deliver the second twin by cesarean section. In studies this risk ranges from 4 to 7%.24,25Indications for delivering the second twin by cesarean section when the first one delivered vaginally are persistent transverse lie of second twin, cord presentation or cord prolapse and CTG concerns without imminent delivery or safe conditions for instrumental application.

If twins are delivered by cesarean section, it is good practise to palpate per abdomen and perform an ultrasound scan prior to section to have an idea of fetal lie. At cesarean as well as at vaginal delivery, the risk of a postpartum hemorrhage is higher. There must be good communication with the anesthetic team, timely administration of oxytocic drugs, tranexamic acid and rapid decision to use intrauterine balloons or brace sutures if required to control bleeding from atony.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- Mode of delivery in twin pregnancies should be discussed in advance, taking in account pregnancy complications, fetal wellbeing, presentation of first twin, parity and women’s choice.

- Twins have an increased risk of late stillbirth and therefore elective delivery is indicated at 33 weeks for MCMA twins, 36 weeks for MCDA twins and 37 weeks for DCDA twins.

- Delivery by cesarean section is recommended for all monochorionic monoamniotic twins, triplets and higher number multiples, conjoined twins and twins complicated by selective growth restriction or when the presenting twin not in cephalic presentation.

- When vaginal birth is the option of choice, continuous monitoring of both babies is recommended as well as attendance by expert personnel confident in the delivery of twins. A multidisciplinary approach with involvement of midwife, obstetrician, anesthetist and neonatologist is recommended.

- Delivery of the second twin poses the higher risk (fetal distress, malposition, cord prolapse) and delivering the second twin by cesarean section occurs in about 5% of the cases.

- Postpartum hemorrhage is more common in twins irrespective of the mode of delivery – intravenous access, active management of third stage and prompt access to uterotonics and blood products should be available.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) of this chapter declare that they have no interests that conflict with the contents of the chapter.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

REFERENCES

Wilcox LS, Kiely JL, Melvin CL, et al. “Assisted reproductive technologies: estimates of their contribution to multiple births and newborn hospital days in the United States”. Fertil Steril 1996;65:361–6. | |

Joseph KS, Kramer MS, Marcoux S, et al. “Determinants of preterm birth rates in Canada from 1981 through 1983 and from 1992 through 1994”. N Engl J Med 1998;339(20):1434–9. | |

Ananth et al. “Epidemiology of twinning in developed countries”. Seminars in perinatology 2012;36:156–61. | |

Kiely JL. “The epidemiology of perinatal mortality in multiple births”. Bull N Y Acad Med 1990;66:618–37. | |

Francisco et al. “Hidden high rate of pre-eclampsia in twin compared with singleton pregnancy”. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2017;50:88–92. | |

Hiersch et al. “Incidence and risk factors for gestational diabetes mellitus in twin versus singleton pregnancies”. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2018;298(3):579–87. Doi: 10.1007/s00404–018–4847–9. Epub 2018 Jul 3. | |

Rebarber et al. “Intrauterine Growth Restriction in Twin Pregnancies: Incidence and Associated Risk Factors”. American Journal of Perinatology 2010;28(4):267–72. | |

Murray et al. “Spontaneous preterm birth prevention in multiple pregnancy”. Obstet Gynaecol 2018;20(1):57–63. Doi: 10.1111/tog.12460. Epub 2018 Jan 28. | |

Draper et al. MBBRACE-UK: 2016 | |

April Holladay (2001–05–09). "What triggers twinning?". WonderQuest. Retrieved 2007–03–22. | |

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologist. Management of Monochorionic Twin Pregnancy. Greentop Guidelines No. 51. London: RCOG, 2016. www.rcog.org.uk/en/guidelines-research-services/guidelines/gtg51. | |

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Multiple Pregnancy: Antenatal Care for Twin and Triplet Pregnancies. NICE Clinical Guideline CG129. London: NICE, 2011. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg129. | |

Ko et al. “Optimal Timing of Delivery Based on the Risk of Stillbirth and Infant Death Associated with Each Additional Week of Expectant Management in Multiple Pregnancies: a National Cohort Study of Koreans”. J Korean Med Sci 2018;33(10):e80 https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2018.33.e80 eISSN 1598–6357·pISSN 1011–8934. | |

Barrett, Hannah, Hutton, Willan, Allen, Armson, Gafni, Joseph, Mason, Ohlsson, Ross, Sanchez, Asztalos et al. for the Twin Birth Study Collaborative Group. “A Randomized Trial of Planned Caesarean or Vaginal Delivery for Twin Pregnancy”. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1295–305. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214939. | |

Van Mieghem et al. “Prenatal management of monoamniotic twin pregnancies”. Obstet Gynecol 2014;124(3):498–506. Doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000409. | |

Tak-Yeung L, Wing-Hung T, Tse-Ngong L, et al. “Effect of twin-to-twin delivery interval on umbilical cord blood gas in the second twins”. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 202;109:63–7. | |

Axelsdóttir I, Ajne G. “Short-term outcome of the second twin during vaginal delivery is dependent on delivery time interval but not chorionicity”. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2019;39:3,308–12, DOI: 10.1080/01443615.2018.1514490. | |

Hjortø S, Nickelsen C, Petersen J, et al. “The effect of chorionicity and twin-to-twin delivery time interval on short-time outcome of the second twin”. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine 2014;27:42–7. | |

Shunji Suzuki, Fumi Kikuchi, Nozomi Ouchi, et al. “Risk Factors for Postpartum Hemorrhage after Vaginal Delivery of Twins”. J Nippon Med Sch 2007;74:414–7. | |

Begley CM, Gyte GML, Devane D, et al. “Active versus expectant management for women in the third stage of labour”. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2011;Issue 11. Art. No.: CD007412. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD007412.pub3. | |

Hofmeyr GJ, Hannah ME. “Planned caesarean section for term breech delivery”. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003;(3):CD000166. | |

Hofmeyr GJ, Barrett JF, Crowther CA. “Planned caesarean section for women with a twin pregnancy”. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;(12):CD006553 | |

Suzuki S. “Risk factors for emergency cesarean delivery of the second twin after vaginal delivery of the first twin”. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2009;35(3):467–71. | |

Persad VL, Baskett TF, O'Connell CM, et al. “Combined vaginal-caesarean delivery of twin pregnancies”. Obstet Gynecol 2001;98(6):1032–7. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards programme CLICK HERE)