This chapter should be cited as follows:

Khalil A, Mumford V, Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.412883

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Obstetrics Module

Volume 11

Labor and delivery

Volume Editor: Dr Edwin Chandraharan, Director Global Academy of Medical Education and Training, London, UK

Chapter

Diagnosis and Management of Preterm Labor

First published: February 2021

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

INTRODUCTION

Preterm labor is defined as regular uterine contractions with progressive cervical dilation at less than 37 weeks of gestation. This may or may not be accompanied with cervical effacement.

Preterm birth is defined as delivery of a live baby before 37 weeks of gestation.

Preterm birth is the leading cause of neonatal death and is a major contributor of long-term disability in surviving babies.1 The most common sequelae seen in these surviving babies include:2

- Learning difficulties;

- Developmental delay;

- Cognition delay;

- Cerebral palsy;

- Hearing impairment;

- Visual impairment.

Around 75% of preterm deliveries occur after preterm labor, which may or may not be preceded by preterm prelabor rupture of membranes (PPROM).3 Therefore, early diagnosis and management of preterm labor is central to improving health care for mothers and newborns. The World Health Organization (WHO) have identified preterm birth as one of the top ten research priorities by 2025. The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals include a target to end global preventable neonatal deaths by 2030.4,5 This chapter addresses the etiology, prevention, diagnosis and management of preterm labor.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

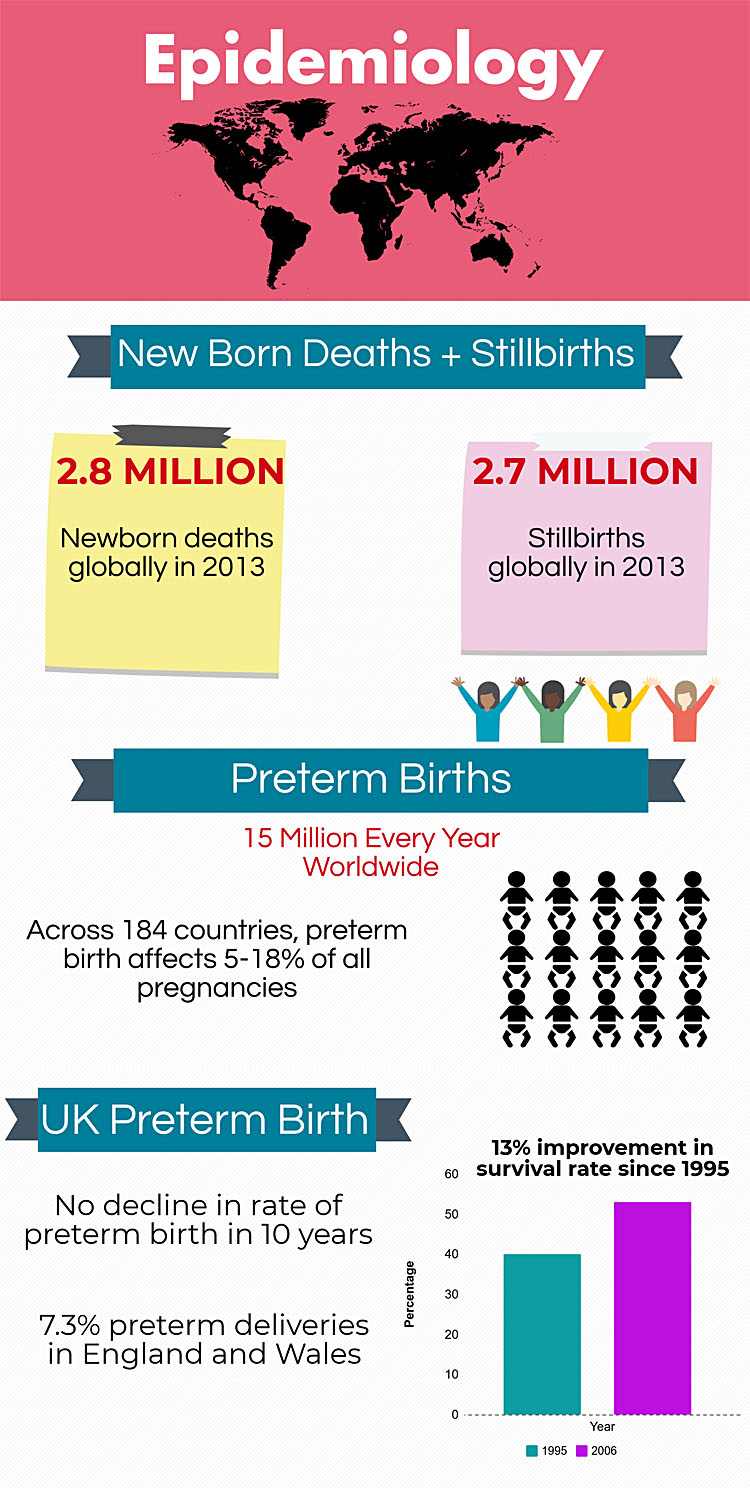

In the UK preterm birth is the largest cause of neonatal mortality and morbidity. In 2012 England and Wales saw a rate of 7.3% preterm deliveries from all live births, as seen in Figure 1, this was equivalent to more than 52,000 preterm babies.3 In the UK, over the past 10 years there has been improvement of survival rate for babies from 40% in 1995 to 53% in 2006; however, there is no change in disability rate of surviving babies.3

ETIOLOGY

It has been suggested that preterm labor is a syndrome rather than a single condition, due to it being attributed to many pathological processes.

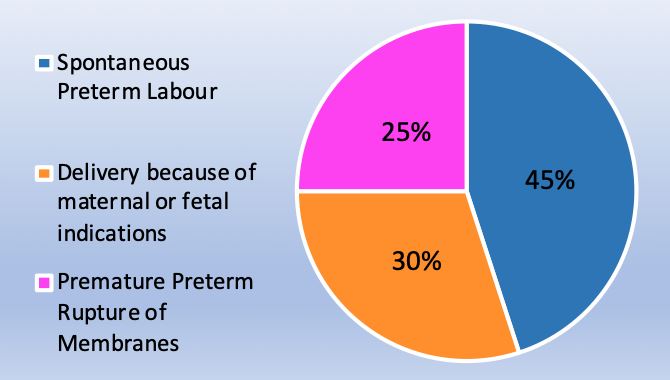

Two-thirds of preterm births occur after preterm labor from PPROM or spontaneous preterm labor with intact membranes, and one-third are medically indicated due to complications with mother or fetus, seen in Figure 2.8

2

Percentage etiology of preterm birth due to medical indications, PPROM or spontaneous labor.8

From 1989 to 2001, it has been shown that birth rate due to PPROM and spontaneous preterm labor decreased; however, the medically indicated preterm birth rate increased by as much as 50% by 2001.8

Spontaneous preterm labor etiology

- Infection – it has been seen that in as many as one in three of preterm neonates, the amniotic fluid contains infection; however, these are largely subclinical.9 Of amniotic infection cases, 30% are identified in the fetal circulation. These fetuses are at risk of multiorgan involvement and complications such as cerebral palsy or chronic lung disease.6 Extrauterine infections also show an association with preterm delivery, such as malaria, pyelonephritis or pneumonia.6

- Vascular disease – 30% of preterm labors show placental lesions where the placental vessel lumens fail to expand. These can lead to preterm labor or pre-eclampsia in some women.6

- Decidual senescence is the process whereby the basal plate of the placenta, which is in direct contact with the uterine wall, deteriorates prematurely. This could lead to implantation failure, fetal death and preterm deliveries.6

- Breakdown in maternal–fetal tolerance – immune tolerance is required by the mother, as the fetus and placenta both express paternal antigens. A breakdown of tolerance can lead to allograft rejection, leading to chronic chorioamnionitis which could lead to preterm labor.6

- Decline in progesterone action – progesterone maintains the pregnancy state, a decline in progesterone induces cervical ripening and spontaneous abortion or preterm labor.6

- Uterine over distension – the uterus becomes overdistended in multiple pregnancies or polyhydramnios. The stretching of the myometrium releases inflammatory cytokines which can stimulate uterine contractility and preterm labor.6

- Maternal stress – emotional or physical stress can produce maternal and fetal cortisol which subsequently can lead to preterm labor.6

Most common indications of preterm birth include:10

- Chorioamnionitis;

- Gestational hypertension, pre-eclampsia or eclampsia;

- Intrauterine demise;

- Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR);11

- Placental abruption;

- Abnormal fetal monitor findings.

RISK FACTORS

There are particular factors which are implicated as increasing the risk for preterm delivery. These risk factors can be identified early and the pregnancy can be monitored and managed as required.

Risk factors are listed below, from this list the two most important predictors of spontaneous preterm birth include a maternal history of spontaneous preterm birth and an incompetent cervix.

Most common risk factors for preterm labor:10

- History of spontaneous preterm birth;

- Incompetent cervix or history of cervical trauma;

- Uterine abnormality;

- PPROM in current pregnancy;

- Antepartum hemorrhage;

- Uterine overdistension due to multiple pregnancies or polyhydramnios;

- Fetal anomaly;

- Second trimester bleeding;

- Infection such as chorioamnionitis or bacterial vaginosis with history of preterm birth;

- Lifestyle: smoking, drugs, stress and domestic violence;

- Demographic factors: maternal weight <55 kg or maternal age <18 years and >35 years.

SCREENING

In the UK routine screening for preterm labor is not undertaken, as per the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines. There are no interventions to reduce risk, prevention is only considered in high-risk women, such as those with a previous preterm delivery.

Possible screening options are detailed below.

Lower genital tract infection screening

A Cochrane review looked at the results of women screened for lower genital tract infection. There were two groups of women, both groups were screened, but only one group was treated for bacterial vaginosis, Trichomonas vaginalis and candidiasis. The control group were not given treatment for infection, nor were they told if they had an infection. The review found that women who received treatment had:

- Lower rate of preterm birth, 3% as compared to 5% in the control group;12

- Lower incidence of low birth weight (2500 g or less) and very low birth weight (1500 g or less) babies born;12

- The authors also reported that for each of the <1900 g preterm births averted,€60,262 would be saved.12

A review by Romero et al. summarized that antibiotic treatment of asymptomatic women with bacterial vaginosis does not reduce the rate of preterm delivery.6

Cervical length

Cervical length measurement is not routinely screened for in the UK. Women are referred for transvaginal ultrasound cervical length measurement between 16 and 34 weeks' gestation if they are deemed at risk of preterm labor.

A systematic review and meta-analysis found that screening using cervical length by transvaginal sonography is associated with a lower incidence of preterm birth in singleton pregnancies with threatened preterm labor. A group of women in threatened preterm labor were randomized into two separate groups:

- Cervical length screening with knowledge of the results: 22.1% rate of preterm birth.13

- Cervical length screening with no knowledge of the results: 34.5% rate of preterm birth.13

A systematic review and meta-analysis found that measuring changes in transvaginal sonographic cervical length over time is not a clinically useful test. This does not predict preterm birth in women with singleton or twin gestations. Measuring a single cervical length between 18 and 24 weeks of gestation appears to be a better predictor of preterm birth than changes in cervical length over time.14

A Cochrane review looked at the use of repeated digital cervical assessment as a screening tool to identify women at risk of preterm labor. The review compared repeat digital cervical assessment to no internal examination and found that no evidence supported the use of repeated digital cervical assessment.15 One of the trials in the Cochrane review15 saw no significant difference in:

- Preterm birth before 34 weeks;

- PPROM;

- Hospital admission before 37 weeks;

- Cesarean section rate;

- Tocolytic administration;

- Low birth weight and very low birth weight;

- Stillbirth;

- Neonatal intensive case admission.

Fibronectin

Fibronectin is not advised for routine screening in the UK.10 A Cochrane review found that testing for fibronectin can significantly decrease preterm birth rate, the control group had a preterm delivery of 28.6% and the fibronectin screened women who were managed accordingly, had a preterm delivery of 15.6%.16

However, no other data were available for fetal outcomes, etc. and the Cochrane authors concluded that there is not sufficient evidence to recommend its use.

PREVENTION

There are a few methods of prevention that can be used in mothers at high risk for preterm delivery. High-risk women are generally those with a previous preterm delivery. NICE recommends cervical cerclage and vaginal prostaglandin routinely for high-risk women. This section considers research on other methods of prevention.

Women at increased risk of preterm labor, should be given information and support early on in their pregnancy. It should be borne in mind that the woman and her family may be anxious. Oral and written information can be given describing the signs and symptoms of preterm labor and also the care she may be offered.

Bed rest

Bed rest as a means to prevent preterm labor is considered due to the fact that hard work and physical activity may be associated with uterine activity. A Cochrane review of bedrest in singleton pregnancies at high risk of preterm birth concluded that bed rest compared to the control group of expectant management saw no significant difference in preterm delivery. With a preterm birth of 7.9% in the bed rest group and 8.5% in the control group.17 This review concluded that there is no evidence supporting or refuting the use of bed rest to prevent preterm birth.17

Another Cochrane review looked at the use of relaxation techniques for women during preterm labor, however, there was no effect on preterm birth.18 When looking at the use of relaxation techniques for women not in preterm labor, there were some benefits on maternal anxiety, an increased baby birth weight and also an increase in vaginal delivery compared to cesarean section.18 However, further research is required.

Antibiotics

The use of prophylactic antibiotics is recommended for consideration by NICE and the Royal College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (RCOG) in women with PPROM. Erythromycin 250 mg 4 times daily is the antibiotic of choice, given for 10 days or until labor is established, whichever is sooner.3,19 Co-amoxiclav should not be offered. In women who cannot take erythromycin, oral penicillin for a maximum of 10 days or until established labor should be considered, whichever is sooner.

Antibiotics are not offered if results for PPROM show negative for amniotic fluid on speculum or for insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 (IGFBP-1) or placental alpha-microglobulin-1 (PAMG-1).3

Antibiotics are not recommended by NICE to be given routinely to women in preterm labor with membranes intact.3

Pessary

This is a non-invasive alternative to cervical cerclage in women with a short cervix of 25 mm or less. This is not routinely recommended in the NICE preterm labor guidelines.3

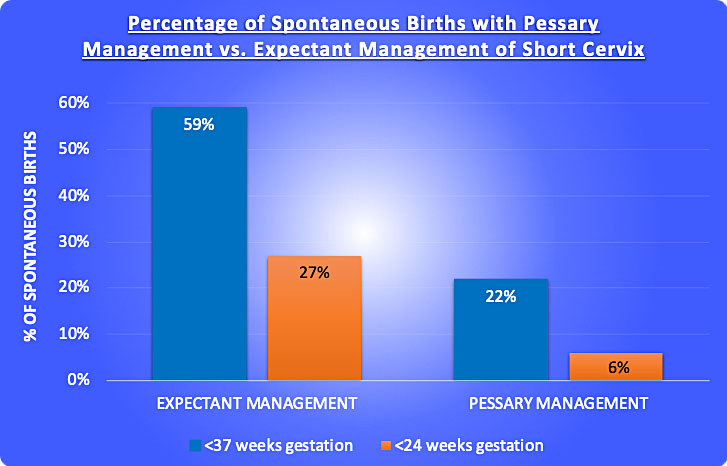

A Cochrane review found that when comparing the use of the pessary to expectant management of short cervix, there was a significant decrease in incidence of spontaneous preterm delivery, this is seen in Figure 3.20 This review also found that woman using the pessary used less tocolytics and corticosteroids. However, this review also stated more trials are needed.

3

Percentage of spontaneous preterm births with pessary management versus expectant management.20

Vaginal progesterone

Vaginal progesterone is offered to women with no history of spontaneous birth or mid-trimester loss, but in whom their cervical length is measured as <25 mm when they are 16 and 24 weeks' gestation.3

Vaginal progesterone can be considered in women with a cervical length of <25 mm between 16 and 24 weeks' gestation, plus a history of:

Cervical cerclage

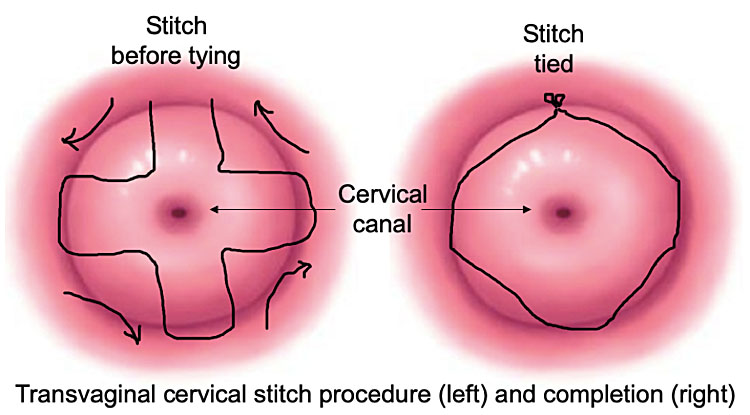

Cervical cerclage is the placing of a stitch around the cervix to prevent cervical dilation leading to preterm labor, seen in Figure 4. Cervical cerclage can be done as prophylaxis in certain groups of women or as a ‘rescue’ measure in women who have a dilated cervix and exposed, unruptured membranes at 16–27 weeks of pregnancy.3

4

Cervical cerclage stitch.

Cervical cerclage is considered in women with a cervical length of <25 mm when they are measured between 14 and 24 weeks' gestation and who have had any of the following:3

- PPROM in previous pregnancy;

- Spontaneous preterm birth;

- Mid-trimester loss between 16 and 34 weeks’ gestation;

- Have a history of cervical trauma such as cone biopsy, large loop excision of the transformation zone or radical diathermy.

Rescue cerclage must take into account the extent of cervical dilation and the gestational age, be aware that the earlier the gestational age the greater the benefits.3

‘Rescue’ cerclage is contraindicated in:3

- Signs of infection;

- Active vaginal bleeding;

- Uterine contractions.

DIAGNOSIS

Preterm labor is regular uterine contractions with progressive cervical dilation which may or may not be accompanied with cervical effacement. Clinical assessment of a women with intact membranes includes:

- Clinical history taking: estimated date of delivery, ultrasound scans, antenatal notes.

- Maternal observations: pain level, pulse, blood pressure, temperature, urinalysis, vaginal loss, contraction length, strength and frequency.

- Fetal observations: fetal movement in the last 24 hours, fundal height, baby’s lie, presentation, position, and engagement of the presenting part.

- A speculum examination is offered to women to determine if PPROM has occurred. This is carried out by looking for pooling of amniotic fluid. If amniotic fluid is not observed, then consider performing vaginal fluid testing for:

- Digital vaginal examination is offered only if speculum examination cannot assess the extent of cervical dilation.3

MANAGEMENT

If preterm labor is suspected after the clinical assessment, then the gestational age determines the management:

- If the mother is 29+6 weeks' gestation or less, consider tocolysis and maternal steroids.3

- If the mother is 30 weeks' gestation or more, consider transvaginal ultrasound to measure cervical length as a diagnostic test to determine the likelihood of birth within 48 hours:

- If transvaginal ultrasound is not available or not acceptable to measure cervical length, then consider testing fetal fibronectin. This test determines the likelihood of birth within 48 hours for women of 30 weeks' gestation or more. Manage the women as follows:

- If neither transvaginal ultrasound nor fetal fibronectin is available and the mother is 30 weeks' gestation or more, then offer her treatment consistent with her be in diagnosed preterm labor and consider tocolysis and maternal steroids.3

There is no persuasive evidence to show that the inhibition or decrease of uterine contractions can decrease the rate of preterm delivery or improve neonatal outcome. However, inhibiting uterine contractions can achieve short-term prolongation of pregnancy for the administration of steroids or for maternal transfer to tertiary care centers if required.6

MATERNAL CORTICOSTEROIDS

Maternal corticosteroids are considered in preterm labor as they have been demonstrated to reduce the risk of respiratory distress syndrome and intraventricular hemorrhage.19 Betamethasone or dexamethasone can be given as two doses of 12 mg intramuscular injections 24 hours apart. It has been demonstrated that there is no risk of neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis, neonatal sepsis or APGAR score of less than 7 at 5 minutes.19

Repeat courses of corticosteroids should not be routinely offered, but take into account:

- Gestational age.3

- The likelihood of delivery within 48 hours.3

- Time interval since the last course of corticosteroids.3

Care needs to be taken when considering corticosteroids as they have certain side effects:

- Will increase maternal blood sugar.10

- Will increase white blood cells.10

- Caution in the presence of cardiac disease, active tuberculosis, gastric ulcers, chorioamnionitis and placental abruption.10

NICE recommends considering administering corticosteroids between 23 and 35+6 weeks of gestation in the following situations:

TOCOLYTICS

Tocolytics refer to medications intended to supress contractions. NICE shows that multiple factors are taken into account when making the decision of whether to start a woman on tocolysis:

- Presence of suspected or diagnosed preterm labor;3

- Gestational age at presentation;3

- The likely benefit from maternal corticosteroids;3

- The need to transfer the mother to another unit with neonatal care facilities;3

- The preference of the woman.3

Contraindications:

NICE states:

- Nifedipine is the tocolytic of choice for women between gestational ages 24 and 33+6 weeks with suspected preterm labor plus intact membranes;3

- Nifedipine is the tocolytic of choice for women between gestational ages 26 and 33+6 weeks with diagnosed preterm labor plus intact membranes;3

- Oxytocin receptor antagonists are the tocolytic of choice in women whom nifedipine is contraindicated;3

- Do not offer betamimetics for tocolysis.3

RCOG concludes that there is insufficient evidence in support of the administration of tocolytics in women with PPROM. This is due to an increase risk of chorioamnionitis, a 5 minute APGAR score of <7 and an increased need for ventilation support.19 There is also no significant benefits to the neonate.19

MAGNESIUM SULFATE

Magnesium sulfate has been shown to offer neuroprotection for the fetus, reducing fetal cerebral palsy and motor dysfunction.3,19

NICE and the RCOG recommend that magnesium sulfate administration is considered during:

Magnesium sulfate has the greatest benefit before 30 weeks of gestation.3,19

RCOG suggests offering magnesium sulfate between 24–29+6 weeks of gestation after PPROM.

NICE suggests offering it between 24 and 33+6 weeks of gestation during established preterm labor and planned preterm delivery within 24 hours.

An intravenous (IV) bolus of 4 g of magnesium sulfate is administered over 15 minutes which is followed by IV infusion of 1 g per hour until the delivery or for 24 hours, whichever comes sooner.3

Maternal monitoring for toxicity every 4 hours is required, or more frequently if there are signs of renal failure.3 The following signs are monitored:

IN UTERO TRANSFER

In utero transfer is the transfer of the mother to a hospital with an appropriate neonatal unit prior to the delivery of the baby. Babies born at hospitals with neonatal intensive care units have a lower risk of mortality and morbidity. If transfer is required, this is one reason to consider tocolysis to inhibit uterine contractions for short-term prolongation of pregnancy.3,6

The following factors should be considered when discussing in utero transfer:

- Availability of appropriate care level for neonate and mother;10

- Availability of transportation;10

- Availability of an appropriate skilled health care professional to travel with the mother;10

- Stability of the mother and fetus;10

- The time needed to travel;10

- The risk of delivery whilst transferring.10

The risk of delivery is determined by the effect of tocolytics on contractions if they were administered, the amount of cervical dilation, the length of time previous labors took and the presentation of the fetus.10

INTRAPARTUM FETAL HEART MONITORING

When considering fetal heart monitoring options, discuss with the mother how a normal cardiotocography trace is reassuring, however, an abnormal trace does not necessarily indicate that the fetus is hypoxic or acidotic.

NICE indicate that there is an absence of evidence that cardiotocography does, in fact, improve the maternal or fetal outcome in preterm labor, compared to intermittent auscultation.

Fetal heart monitoring is carried out when identifying chorioamnionitis in a woman.3,19

MODE OF DELIVERY

A discussion is required with the mother about the risks and benefits of both cesarean section and vaginal birth. There are increased difficulties associated with cesarean sections performed in preterm birth.3 There is an increased risk of requiring a vertical uterine incision which may have implications for future pregnancies.3 Although there is very limited evidence, there are currently no known benefits or harms to the baby from cesarean section.3

Consider cesarean section for women in established preterm labor between 26 and 36+6 in whom the fetus is in breech presentation.3

A Cochrane review assessed the effects of planned immediate cesarean section versus planned vaginal delivery during preterm labor. This review found that there was no significant difference between the two delivery modes with respect to:

- Infant birth injury;21

- Birth asphyxia;21

- Perinatal deaths;21

- Neonatal admission to a specialized neonatal unit;21

- APGAR score <7 at 5 minutes;21

- Neonatal seizures;21

- Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (HIE);21

- Respiratory distress syndrome (RDS);21

- Maternal postpartum hemorrhage.21

There was a significant advantage for women in the vaginal delivery group with respect to puerperal pyrexia and maternal infection.21 However, more research is required before a policy can be formed from this review.

RCOG does not routinely recommend cesarean section for breech presentation in spontaneous preterm labor, the mode of delivery depends on the stage of labor, fetal well-being, type of breech presentation and skill of operator in vaginal breech delivery.22 Cesarean section is recommended in preterm breech presentation when delivery is planned due to indications such as maternal and/or fetal compromise.22

ROLE OF ANTIBIOTICS

Intrauterine infection should be assessed by a combination of clinical assessment, maternal C-reactive protein (CRP) and white blood count, plus fetal heart rate. These tests should not be used in isolation to diagnose infection.19

According to NICE and RCOG, antibiotics should be given following diagnosis of PPROM. Preferably erythromycin 250 mg four times per day is given for 10 days or up until the woman is in established labor, whichever is sooner.3,19

Do not offer co-amoxiclav for prophylaxis, due to its increased risk of neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis.3,19

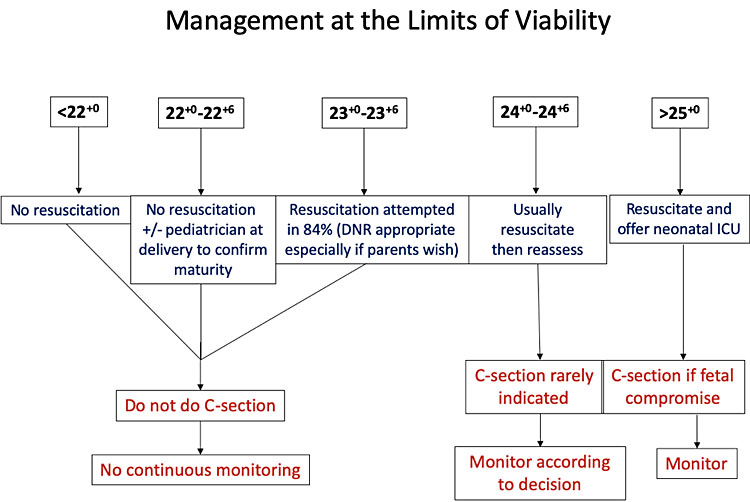

MANAGING PREGNANCIES AT THE LIMITS OF VIABILITY

Delivery at the threshold of viability refers to babies born at 23–24+6 weeks of gestation.

There is international consensus that babies born at 22 weeks of gestation have no hope of survival.23 Although a study by EPICure showed a survival rate of 2% of babies born at 22 weeks of gestation in 2006.24

22+6 weeks of gestation is considered to be the cut-off for human viability. Delivery between 23 and 24+6 weeks of gestation is the most challenging for neonates.23

Studies in England by EPICure saw an increase in survival of live born babies between 1995 and 2006:

- An overall increase in survival of babies born at 22 weeks to 25 weeks’ gestation, from 40% to 52% survival rate (from 1995 to 2006).24

- However, the morbidity rates of the surviving babies was the same in both years for bronchopulmonary dysplasia, major cerebral abnormality or weight and/or head circumference <2 standard deviations.24

- Retinopathy of prematurity rates of the surviving babies increased from 13% to 22% (from 1995 to 2006).24

Neonatal survival is improved when babies at the limits of viability are delivered at an appropriate level neonatal unit. For this reason in utero transfer, if required, will optimize management.23

During preterm delivery, it is discussed whether monitoring the fetal heartbeat is appropriate, and as with fetuses at the threshold of viability, there is the option not to monitor the fetal heart rate. For women at 23–25+6 weeks of gestation a senior obstetrician should be involved in discussing whether and how to monitor the heart rate.3

5

Managing births at the limits of viability. DNR, do not resuscitate.

POSTNATAL INVESTIGATIONS

Investigations after a preterm delivery are carried out to try to determine the cause, if possible. These tests can also be carried out in cases of stillbirth.

A stillbirth is a baby delivered with no signs of life, known to have died after 24 completed weeks of pregnancy. Intrauterine fetal death refers to babies with no signs of life in utero.25 An autopsy can be carried out for the purpose of providing information to the bereaved family on the immediate cause and timing of intrauterine death or relevant factors in the death. The parents should be advised that for almost half of stillbirths no specific cause is found. Autopsy examinations can only be carried out with the informed consent of the parents or a person of qualifying relationship as defined by the Human Tissue Act. Concomitant diseases may be identified, particularly any diseases which may affect future pregnancies, such as maternal diabetes, malformation, growth restriction, etc.26 Genetic disease can also be detected and to determine the likelihood of a risk in future pregnancies.26 The postmortem looks at the external fetus, autopsy, microscopy, X-ray, placenta and cord.25

Common pathologies encountered in autopsy:

- Hypoxia;26

- Growth restriction;26

- Infection;26

- Congenital malformation;26

- Blood loss;26

- Trauma;26

- Hydrops fetalis;26

- Fetal conditions secondary to maternal disease, such as diabetes, hypertension or pre-eclampsia;26

- Disease of the placenta and umbilical cord.26

Maternal investigation after an intrauterine fetal death:

- Hematology and biochemistry to test for pre-eclampsia, multiorgan failure in sepsis or obstetric cholestasis;25

- Coagulation tests for disseminated intravascular coagulation;25

- Infection tests: blood cultures, midstream urine for infection, vaginal and cervical swabs, serology for viral screen/syphilis/tropical infections;25

- Random blood glucose and HbA1c for diabetes;25

- Thyroid function;25

- Thrombophilia screen;25

- Anti-red cell antibody, anti-Ro, anti-La if hydrops evident.25

Fetal investigation of a late uterine fetal death:

- Fetal Rh status from umbilical blood in mothers who are Rh negative.25 Plus Kleihauer test, if fetus is Rh positive, this tests for fetomaternal hemorrhage. If this is a large hemorrhage then this could be a silent cause of intrauterine death. Also a larger dose of anti-D may be needed as soon as possible.25

- Fetal and placental microbiology of blood, fetal swabs and placental swabs.25

- Karyotype of deep fetal skin, fetal cartilage and placenta.25

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

Screening

- A systematic review and meta-analysis found that screening cervical length by transvaginal sonography is associated with a lower incidence of preterm birth in singleton pregnancies with threatened preterm labor.13

- Another systematic review and meta-analysis found that measuring a single cervical length between 18 and 24 weeks of gestation appears to be a better predictor of preterm birth than measuring changes in cervical length over time.14

Prevention

- It is recommended to consider prophylactic antibiotics in women with PPROM. Give erythromycin 250 mg 4 times daily for 10 days or until labor is established, whichever is sooner.3,19

- A Cochrane review found that when comparing the use of the pessary to expectant management of short cervix, there was a significant decrease in incidence of spontaneous preterm delivery with the use of pessary for short cervix, as compared to expectant management alone.20 However, more research is required as the studies report conflicting results.

- Vaginal progesterone is offered to women with no history of spontaneous birth or mid-trimester loss, but in whom their cervical length is measured as <25 mm when they are 16–24 weeks of gestation.3

- Vaginal progesterone can be considered in women with a cervical length of <25 mm between 16 and 24 weeks' gestation, plus a history of spontaneous preterm birth or mid-trimester loss between 16 and 34 weeks' gestation.3

- Cervical cerclage can be done as prophylaxis in women with a cervical length of <25 mm when they are measured between 14 and 24 weeks' gestation and who have either had PPROM, spontaneous preterm or mid-trimester loss in a previous pregnancy, or history of cervical trauma.3

- ‘Rescue’ cerclage can be done in women who have a dilated cervix and exposed, unruptured membranes at 16–27 weeks of pregnancy.3

Management

- Maternal corticosteroids are considered in preterm labor as they have been demonstrated to reduce the risk of respiratory distress syndrome and intraventricular hemorrhage.19 Betamethasone or dexamethasone can be given as two doses of 12 mg intramuscular injections 24 hours apart. There has been shown to be no risk of neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis, neonatal sepsis or APGAR score of less than 7 at 5 minutes.19 NICE recommends administering a course of steroids between 23 and 35+6 weeks.3

- Tocolytics are intended as a temporary suppression of contractions if there is likely benefit from corticosteroids or the need to transfer the mother to a unit with neonatal care. Also there can be no presence of chorioamnionitis, vaginal bleeding or indications for immediate delivery. NICE states Nifedipine is the tocolytic of choice for women between gestational ages 24–33+6 weeks with suspected preterm labor plus intact membranes.3

- RCOG concludes that there is insufficient evidence in support of the administration of tocolytics in women with PPROM. This is due to an increase risk of chorioamnionitis, a 5 minute APGAR score of <7 and an increased need for ventilation support. There is also no significant benefits to the neonate.19

- Magnesium sulfate has been shown to offer neuroprotection for the fetus, reducing fetal cerebral palsy and motor dysfunction.3,19 NICE and RCOG recommend that magnesium sulfate administration is considered during established preterm labor or planned preterm delivery within 24 hours. Magnesium sulfate has the greatest benefit before 30 weeks of gestation.3,19 The mother is given 4 g intravenous bolus of magnesium sulfate over 15 minutes which is followed by IV infusion of 1 g per hour until the delivery or for 24 hours, whichever comes sooner.3

- The mode of delivery should be is considered and discussed with the mother about the risks and benefits of both cesarean section and vaginal birth. There are increased difficulties associated with cesarean sections performed in preterm birth. There is an increased risk of requiring a vertical uterine incision which may have implications for future pregnancies.3 Although there is very limited evidence, there are currently no known benefits or harms to the baby from cesarean section.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Author(s) statement awaited.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

REFERENCES

Liu L, Johnson HL, Cousens S, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality: an updated systematic analysis for 2010 with time trends since 2000. 2012;379:2151. | |

Mwaniki MK, Atieno M, Lawn JE, et al. Long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes after intrauterine and neonatal insults: a systematic review. Lancet 2012;379(9814):445. | |

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence editor. Preterm Labour and birth. NICE Guideline; 2015. | |

United Nations sustainable development goal: United Nations. The 2030 agenda for Sustainable Development. A/RES/70/1. Sustainable Development Goal 3; ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages. Target Indicator 3.2.2. 2015. | |

Howson CP, Kinney MV, Lawn JE; March of Dimes; PMNCH; Save the Children; World Health Organization. Born too soon: The global action report on preterm birth. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2012. | |

Romero R, Dey SK, Fisher SJ. Preterm Labor: One Syndrome, Many Causes. Science 2014;345(6198):760. | |

Yoshida S et al. Setting research priorities to improve global newborn health and prevent stillbirths by 2025. Journal of Global Health 2016;6(1). | |

Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, et al. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet 2008;371(9606):75–84. | |

Romero R, Gomez R, Chaiworapongsa T, et al. The role of infection in preterm labour and delivery, Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology 2001;15(2):41–56. | |

The Global Library of Women's Medicine (GLOWM). Preterm Labour and Preterm Birth. Advances in Labour and Risk Management (ALARM) Textbook. 4th edn. A.L.A.R.M. International. Chapter 15. | |

Mozurkewich E, Chilimigras J, Koepke E, et al. Indications for induction of labour: a best-evidence review. BJOG 2009;116:626–36. | |

Sangkomkamhang US, Lumbiganon P, Prasertcharoensuk W, et al. Antenatal lower genital tract infection screening and treatment programs for preventing preterm delivery. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015(2). | |

Berghella V, Palacio M, Ness A, et al. Cervical length screening for prevention of preterm birth in singleton pregnancy with threatened preterm labor: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials using individual patient-level data. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2017;49:322–9. | |

Conde-Agudelo A. RR. Predictive accuracy of changes in transvaginal sonographic cervical length over time for preterm birth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;213(6):789–801. | |

Alexander S, Boulvain M, Ceysens G, et al. Repeat digital cervical assessment in pregnancy for identifying women at risk of preterm labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010(6). | |

Berghella V, Hayes E, Visintine J, et al. Fetal fibronectin testing for reducing the risk of preterm birth. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008(4). | |

Sosa CG, Althabe F, Belizán J,, et al. Bed rest in singleton pregnancies for preventing preterm birth. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015(3). | |

Khianman B, Pattanittum P, Thinkhamrop J, et al. Relaxation therapy for preventing and treating preterm labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012(8). | |

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Green-top Guideline No XXXXX: Care of Women Presenting with Suspected Preterm Prelabour Rupture of Membranes. Peer review draft. | |

Abdel‐Aleem H, Shaaban OM, Abdel‐Aleem M. Cervical pessary for preventing preterm birth. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013(5). | |

Alfirevic Z, Milan SJ, Livio S. Caesarean section versus vaginal delivery for preterm birth in singletons. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013(9). | |

Impey LWM, Murphy DJ, Griffiths M, Penna LK on behalf of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Green-top Guideline No. 20b: Management of Breech Presentation. BJOG 2017;124:151–77. | |

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Perinatal Management of Pregnant Women at the Threshold of Infant Viability (The Obstetric Perspective). Scientific Impact Paper No. 41 2014. | |

Costeloe K, Hennessy E, Haider S, et al. Short term outcomes after extreme preterm birth in England: comparison of two birth cohorts in 1995 and 2006 (the EPICure studies). BMJ 2012;345. | |

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Green-top Guideline No. 55: Late Intrauterine Fetal Death and Stillbirth. 2010. | |

Osborn M, Lowe J, Cox P, et al. Guidelines on autopsy practice: Third trimester antepartum and intrapartum stillbirth. The Royal College of Pathologists 2017. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards programme CLICK HERE)