This chapter should be cited as follows:

Spillane E, Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.409593

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Obstetrics Module

Volume 11

Labor and delivery

Volume Editor: Dr Edwin Chandraharan, Director Global Academy of Medical Education and Training, London, UK

Chapter

Organization of Care for Safe Woman-friendly Birth

First published: February 2021

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

INTRODUCTION

Organization of care for safe woman-friendly birth extends beyond labor, birth and the choice of clinical equipment available in the birth room; it starts at the initial consultation with the woman when she books her maternity care. The initial booking appointment gives healthcare professionals the information required to plan care for the remainder of the pregnancy, labor, birth and on into the postnatal period. This can be achieved wherever the woman is in the world and is the foundation for safe woman-friendly care, listening to her wishes and adapting care to support these in the safest possible way. Maternity care should be built around women and the needs of each community because these will differ around the world.

Maternity services and the way care is offered in pregnancy has changed considerably across the globe throughout the past few years and many more women are choosing to give birth in a hospital setting,1 yet a recent systematic review and meta-analysis2 found no difference in adverse outcomes for mothers or babies born at home, in a birth center or in hospital for healthy mothers in high-income areas. However, this may not be a suitable model of care for those in lower-income countries where birth in obstetric-led facilities may be safer. Despite the outcomes found in this study,2 there are still high rates of suboptimal care which result in poor outcomes for women and babies that are not only physical, but also psychological and emotional.1

Maternal health outcomes are measured not only by the mortality and morbidity rates of women and babies, but also have extended to a more holistic approach to outcomes, ensuring women receive safe care and a positive experience. Organization of care for safe woman-friendly birth should happen globally regardless of socioeconomic settings and should be provided using a rounded, human rights centered methodology which is cost-effective and adaptable across different global settings.1 Whilst it is important that evidence-based care is practiced, it is also important to consider the more holistic approaches to care and being aware that not all women will want to have the recommendations imposed on them. It can be easy to think that this is unsafe; however, it is important to remember the human rights of a pregnant woman; listening to individual wishes is vital and choices can still be supported in a safe way with excellent, multidisciplinary planning.

This chapter discusses important aspects of organization of safe woman-centered care based on research and practice. Topics covered include having the organization built around the woman; multidisciplinary working; continuity of care and carer; birth preference planning; listening to women’s wishes and women’s rights; essential equipment required for planning a safe birth; and the birthing environment. All these components together enable families to have positive birthing experiences in a safe environment inclusive of the multidisciplinary team. Each topic discusses the benefits, challenges and practice implications for each and whether it is practically possible in different settings along with alternative suggestions for areas with less resources.

BUILDING THE ORGANIZATION AROUND WOMEN AND CONTINUITY OF CARE MODELS

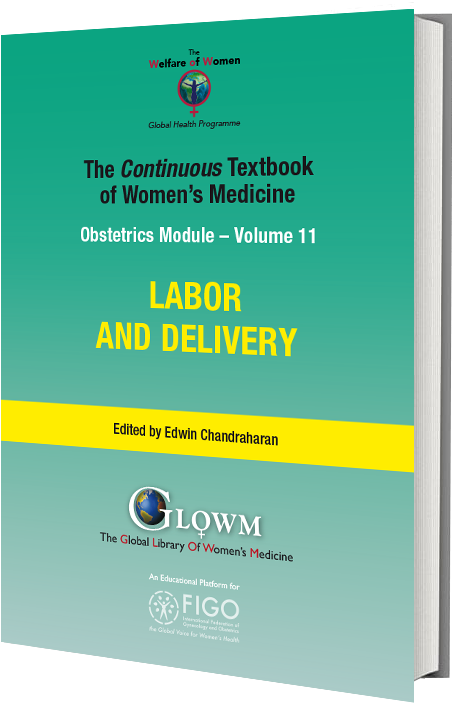

Ultimately, every healthcare professional’s goal is to ensure excellent outcomes for healthy mothers and babies. This means ensuring they are both physically and psychologically well antenatally, intrapartum and postpartum. Organizing care around women not only builds relationships between the healthcare professionals and the women, but also enables women to have an active role in the care they wish to receive. Both these aspects improve safety by building trust and enabling healthcare professionals to close gaps and discontinuities in care thus decreasing disparities in outcomes across services.3 The implications of this for healthcare providers are that maternity services will need to be re-shaped, so women have a named midwife who they are able to contact throughout their pregnancy for advice and a named obstetrician who would be assigned to a midwifery team (Figure 1).4 The named obstetrician would see women requiring obstetric input during their pregnancy and would also act as a point of contact for the midwives in the team for advice and support with more complex cases. This model of care is known as relational continuity of care and has been shown to improve outcomes for women and neonates and improve the experiences for women.4

A Cochrane report comparing midwife-led continuity of care models versus other models of care in maternity services found that the midwife-led model had many benefits including reducing pre-term birth, fetal loss at any gestation, neonatal death and instrumental birth.4 The report found that women were less likely to require intervention and more likely to have improved experiences.4 Another study describes health inequalities globally in the form of ‘Too Much Too Soon’ and ‘Too Little Too Late’.5 Too Much Too Soon is a phenomenon whereby intervention is used too soon and causes harm, rather than improving outcomes for women and neonates, usually seen in middle- to high-income countries.5 An example of this is the increasing cesarean section rate with no difference in improved outcomes.5 The other phenomenon is Too Little Too Late whereby intervention is not used in a timely manner or when needed, contributing to poor outcomes for both women and neonates, this is usually seen in low-income countries.

It has also been suggested that having a global set of maternity guidelines would ensure women across the globe are receiving the same level of care.5 Whilst this is important and would indeed help to improve outcomes by preventing both ‘Too Much Too Soon’ and ‘Too Little Too Late’, this may be difficult to achieve in countries with less resources, particularly with expensive procedures such as screening. However, it may be possible to adopt similar guidelines within the resources of individual countries. Starting with a named midwife with whom women can build trust, countries with limited resources will greatly benefit by ensuring women give birth in the safest environment and having obstetric input in these environments. The stepping stone for organizing safe woman-centered care for labor and birth begins with having a service which is built around the women, ensuring trust between women and healthcare professionals, and improving maternal and neonatal outcomes antenatally, intrapartum and postpartum.

The challenges for implementing continuity of carer are staff shortages and financial constraints. It is a more expensive way of care to set up, but in the long-term the cost savings are evident with a reduction in the adverse outcomes which are improved with this model of care. In areas where this model of care is not practical due to finances and/or lack of available staff, a model which reflects similar benefits can be used by ensuring one-to-one care in labor, allowing women to have birth partners of their choice who they know and trust and ensuring obstetric help is always available.

1

Building care around the woman.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY WORKING

Multidisciplinary team working has been shown to improve outcomes related to labor and birth and to improve the experiences of parents within maternity care. It also improves working relationships and morale for staff. However, the challenge it poses to staff is that it challenges the traditional roles of the wider multidisciplinary team by breaking down barriers between team members. This enables the team to better use their combined expertise holistically for improved patient outcomes both clinically and psychologically.6 A report commissioned to review the safety of maternity services within the UK proposed 12 recommendations, two of which were related to multidisciplinary working.7 The first recognised that safety can be affected by interprofessional relationships, for example differences in opinions and attitudes to care between different professional teams. The second concerned lack of communication between practitioners, specifically at important times such as when making referrals between healthcare professionals, shift changes and during emergencies.7 To improve these potential risks and improve safety, multiprofessional teams need to have a clear purpose with each member understanding their role within the team. In addition, there needs to be effective leadership and excellent communication between practitioners which is both clear and unambiguous.7 This is particularly relevant for teams working on the labor ward where practitioners from a number of professions are required to work together to ensure safety for the birth of the neonate and health of the mother.

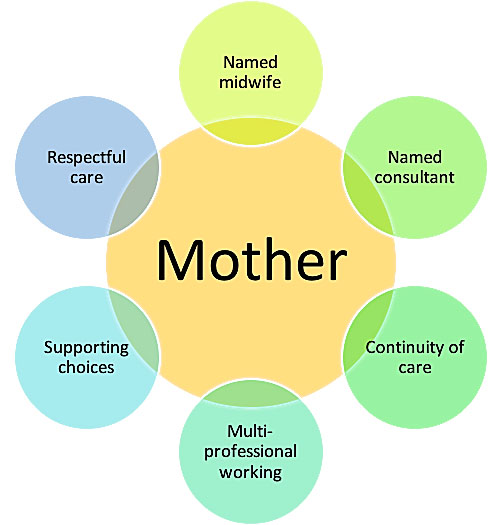

If teams are expected to work together they must train together to ensure effectiveness and efficiency within the team.6,7 Training together has been demonstrated to have positive effects on multidisciplinary team working. This can be achieved in many different ways such as forums for discussing issues, concerns and sharing positive episodes where multidisciplinary team working has been beneficial. It could also be achieved through skills and drills training especially run in real-time, for example, running through a postpartum hemorrhage or shoulder dystocia (Figure 2). By training together there is better understanding of each professional’s role, creating respect amongst staff and different staff groups, improving safety for better clinical outcomes and improving the experience of parents. It is essential for labor ward teams to train together to ensure that wards run effectively, efficiently and safely and that teams at all times have clear unambiguous communication, particularly during emergencies.

Training on labor ward is an excellent way of improving safety by training in the actual environment where the team works on a daily basis, making it more realistic to normal working practice and also making it more relevant to the practitioners.7 The training should be run by a clinician who takes notes on various aspects of the training such as communication between multiprofessional practitioners, leadership within the team, knowledge of individual roles and responsibilities and clinical skills. Training on labor ward should be a core activity which involves simulation of various skills and emergencies,7 this will again improve the many aspects which increase the safety of labor and birth and is intrinsic to the organization of safe care.

2

Multiprofessional team training together during a skills and drills session.

BIRTH PREFERENCE PLANNING AND LISTENING TO WOMEN’S WISHES AND WOMEN’S RIGHTS

Risk and choice are two elements of obstetrics which are high on the maternity agenda. It could be argued that society is becoming more risk aware which has led to changes within the midwifery and obstetric culture, such as increasing fear amongst healthcare professionals. However, choice is also a key concept which is more prevalent in modern times.8 The difficulty in obstetrics is supporting choice whilst reducing risk, a conundrum to which there is no real answer. In more recent years there has been an increase in the number of women requesting care which does not conform to hospital guidelines, which requires birth attendants to have the ability to normalize complex labors and births. Birth attendants must evolve and move away from dichotomous models of care to become more skilled practitioners who are able to move easily between social and technocratic models of care.9 Skilled birth attendants supporting this model of care do not do this alone and maintain excellent communication between health professionals and have excellent professional relationships with the wider multidisciplinary team.9

Birth preference planning is one option for organizing care for a safe birth that is woman centered and supporting maternal choice whilst also trying to minimize any risk to mother and child during labor and birth. Birth preference planning is about informing parents of the benefits and limitations of their choices, complexities, care, mode of birth and place of birth to enable them to make fully informed decisions about the care they wish, or do not wish, to receive. Making informed decisions involves having a level of knowledge and comprehension, and in order to ensure parents have this understanding, in-depth conversations need to take place over a number of visits.8 Time constraints can make it difficult to have these conversations, but they should start early in pregnancy so that they can be revisited throughout the antenatal period and parents have time to consider their choices and ask questions in relation to these. These conversations should be multidisciplinary for complex pregnancies, especially when women may be requesting care which has not been recommended. Following these conversations, once the parents are happy with the choices they have made with regards to their labor and birth, a birth preference plan can be written. This should support their choices and outline the information which has been discussed, the recommendations which have been made (and why they have been made) and a plan of care for when the mother’s labor begins. This ensures that staff have a clear plan to follow, reducing the risk of miscommunication and ensuring that all healthcare professionals involved are aware of their roles and responsibilities.

Birth preference planning is particularly important in rural areas where remoteness and rurality poses many challenges for the healthcare professionals involved in planning and offering safe woman-centered care. Some of these challenges include differences in roles in the wider obstetric team, the clinical confidence and competence of staff and multiprofessional training.8 Birth preference planning will need to include the added risk associated with rural areas ensuring a robust plan is in place in the instance of an adverse event to ensure the safety of mothers, neonates and staff. Birth preference planning involves making a risk assessment of the chosen place of birth and mode of birth, identifying what the risks are and putting measures in place to reduce the likelihood of an adverse outcome associated with the risk occurring. It takes into account human factors, equipment-related factors and organizational factors.

Human factors include thinking about what would happen in an emergency situation, what staff are available, what their roles are and who, if anyone, is on call in such circumstances. Birth planning should ensure that competent and experienced staff are available to care for mothers in these instances and that the training of healthcare professionals is up-to-date. This should include planning a skills and drills session to ensure staff are familiar with the emergency procedures including a clearly documented plan to ensure excellent communication between staff and that staffing is of a safe level.8

Equipment-related factors include ensuring all necessary equipment and emergency drugs are available at all times. Risks increase when equipment is not working, unavailable or not fit for purpose. It is also important that staff are familiar with equipment which is available and particularly with equipment which they do not use regularly. In less-developed countries it is important that healthcare workers are equipped with essential equipment to reduce risks. This is not always possible in less--resourced countries, but encouraging women to birth in medical units where there may be more equipment available may be an important consideration. Emergency drugs are not always available in these areas and therefore it is important that staff are aware of the emergency procedures which can be used instead to help reduce risk, for example where emergency drugs for postpartum hemorrhage are not available, by ensuring practitioners are competent and confident in the use of bimanual compression.8

Organizational factors include the environment within which a mother gives birth, this will include transport in an emergency which is particularly relevant in rural and less--resourced areas. These risks can be increased due to poor weather conditions and poor transport links.8

Case study

A mother in her second pregnancy attends antenatal clinic and informs you she is worried about the birth of her second child because she had a previous traumatic birth. The mother had an emergency cesarean section at 8 cm dilated for fetal distress, she had a postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) of 1.8 liters. She is requesting a homebirth for her second pregnancy with the use of a birthing pool.

There are no medical co-morbidities, she has a raised BMI of 37.

How would you plan care for this mother?

What would be your recommendations?

Which healthcare professionals would you involve?

What plan would you put in place to ensure safe care which is centered around her wishes?

Conversation should start early in pregnancy and continue revisiting the mothers birth plan throughout ensuring she is aware of the risks associated with vaginal birth after cesarean, PPH and raised BMI.

Referral to obstetric consultant for consultation.

Referral to anesthetist for discussion regarding analgesia, assessment of airway in case of the need of intubation for general anesthetic, assessment of ability to have epidural.

Recommendation would be for labor and birth in an obstetric led unit in view of increased risk of uterine rupture, PPH, raised blood pressure, pre-eclamptic toxemia and shoulder dystocia.

Discussion about the use of an alongside birth center instead of a homebirth which would increase safety despite it not being the recommendation. It is safer to labor and birth in an alongside birth center rather than at home.

This topic can be quite controversial because healthcare professionals will want to ensure the safest possible care and make recommendations based on the available evidence. However, many people choose to go against the recommended clinical advice and there may be many factors which affect these choices and decisions. It is important to understand why people make certain choices and to respect the decisions of mothers during pregnancy and birth regardless of whether we agree with them or not. Our own feelings and biases must not affect the information we give, the choices we offer or the way in which we offer them. This can be difficult especially when a mother might be making a decision which is not evidence-based or in the best interest of her own health or the health of her unborn child. The legalities of listening to women and supporting their choices is clear, so long as it is evident that all the information regarding the limitations and benefits of any given procedure has been given to the mother and they have the capacity to make decisions maternal choice must be respected.10 This information is based on the Human Rights Act (1998) which is part of UK law and allows women to make choices about their care and to be treated with dignity and respect at all times.10 These human rights are not universal and therefore differ from country to country. Governments are attempting to endorse human rights globally and are affiliating with multilateral organizations to do so.11 This initiative should see an improvement in the human rights of women for labor and birth ensuring their choices are supported on a global level.

Research has shown mothers value appropriate clinical interventions.5 Pertinent information given at the appropriate time in pregnancy and/or labor allows mothers to make decisions over their care and to receive support from healthcare professionals whilst still maintaining their dignity and retaining some jurisdiction over their care.5 It is important that healthcare professionals provide evidence-based information and recommendations and apply these recommendations in a respectful manner taking into account the individual mothers personal, cultural and medical needs. This is fundamental in safeguarding universal access to quality obstetric care.5 It is essential effective planning and organization of care occurs prior to labor, which is not a safe time to counsel women in their choices, although at times this is unavoidable.

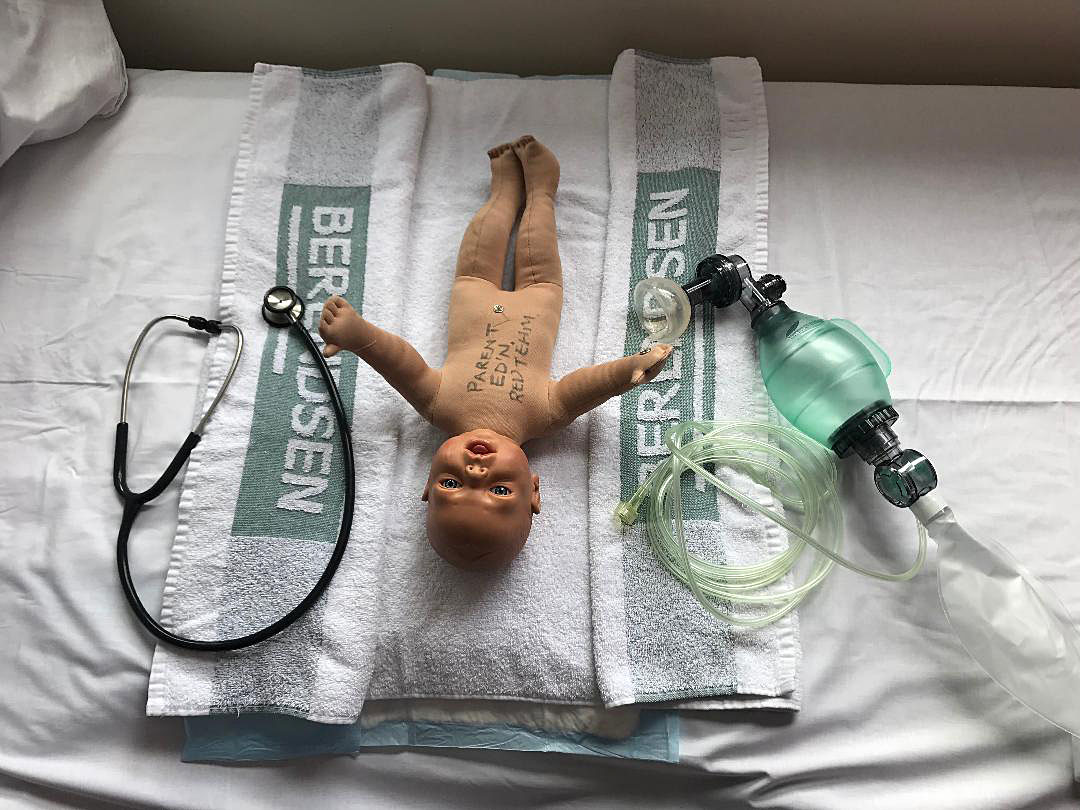

THE BIRTHING ENVIRONMENT AND ESSENTIAL EQUIPMENT FOR BIRTH

The birth equipment deemed as essential in the birth room will differ depending on the socioeconomic status of the country within which the healthcare facility resides. In developed countries like those in the western world, the essential equipment in the birth room will be more extensive than that available in less-developed countries. In order to improve the safety of labor and birth for both women and neonates there needs to be suitable equipment available to reduce the risk of infection, ensure maternal health, resuscitation of both mother and neonate, and for preventing and resolving complications and emergencies associated with labor and birth. However, this equipment is not always available due to the limited availability of resources and the place of birth. The equipment available in a hospital setting is greater than that for a homebirth, likewise the equipment available within an obstetric-led unit will be greater than that of midwife-led facility. This section aims to show what is believed to be essential equipment in a variety of different settings in both developed and less-developed countries (Figures 3–7).

3

A birthing room on an obstetric-led unit. With thanks to St George’s University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust for permission to use the photos.

4

A birthing room in a midwife-led unit. With thanks to St George’s University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust for permission to use the photos.

Within an obstetric-led setting in developed countries, the resources available are much greater. As a consequence, there is more equipment available to increase safety and manage a number of eventualities associated with labor and birth. Some of this equipment may not be deemed ‘essential’ by all, but is by those who use it on a daily basis within their working environment. The equipment in Table 1 is deemed essential within an obstetric-led delivery suite/labor ward within the UK.

1

Essential equipment within an obstetric-led delivery suite/labor ward within the UK.

Essential equipment | Use |

Delivery pack containing 2 x bowls, Spencer-Wells forceps, cord scissors, episiotomy scissors, 5 x swabs, cord clamp | The two bowls are used for a water container for cleaning and as a container for the placenta. Spencer-Wells forceps are used to clamp the umbilical cord. Cord scissors are used to cut the umbilical cord. Episiotomy scissors are a long pair of scissors for cutting an episiotomy in the case of delayed progress in combination with fetal distress, prior to an instrumental birth or preventing severe perineal trauma. Swabs are used for perineal support, perineal compress, cleaning the area and checking the perineum for trauma. Cord clamp is used to clamp the umbilical cord prior to cutting it |

Towel | To dry the baby and keep it warm. Used for stimulation at birth |

Syringe and needle | For infiltrating the perineum with local anesthetic in case of episiotomy or suturing |

Artery clamps | To hold blood vessels closed which may be bleeding. Also used for holding the needle for suturing |

Suture material | For perineal repair |

Local anesthetic | To infiltrate the perineum for episiotomy or perineal repair |

Sterile gloves, sterile gown, apron, eye protection goggles | Personal protective equipment for staff and to reduce the spread of infection |

Neonatal resuscitation equipment – resuscitaire or bag valve mask, stethoscope, suction, laryngoscope, guedal airway | For quick resuscitation of the neonate |

Ventouse | To aid the birth of the neonate for prolonged progress in the second stage and malposition |

Forceps | To aid the birth of the neonate in the case of prolonged second stage and/or malposition |

Oxytocics | A drug used in the management of postpartum hemorrhage. For use to augment labor in the incidence of prolonged progress in the first or second stage of labor (should be used with caution) |

Misoprostol | A drug used in the management of postpartum hemorrhage |

Tranexamic acid | A very cheap drug which has been shown to help in the management of postpartum hemorrhage |

Sphygmomanometer and stethoscope | To monitor blood pressure during labor and in the postpartum period |

Clock | To monitor timings for birth and maternal observations, e.g. maternal pulse |

Thermometer | To monitor maternal temperature during labor and in the postpartum period |

Delivery bed with lithotomy poles | For use with instrumental birth |

Hand-held Doppler, pinnard stethoscope, cardiotocograph (CTG) | For monitoring the fetal heart in labor |

5

Delivery pack used in a UK hospital for delivery suite, midwifery-led unit and home births.

6

Suturing pack used within a UK hospital for use across all areas of practice.

In a midwife-led setting much of the equipment would be available but there would not be the availability of instruments to aid the birth of the neonate. There would also be alternative equipment such as a birthing couch instead of a delivery bed, a birth pool and birthing balls, beans bags and mats to allow women to move freely in positions of their choice to aid optimal fetal positioning for labor and birth. It is essential in this setting that procedures are in place, and practiced, for transfer of women to an obstetric-led facility if required.

7

Alternative equipment used to aid mobilization during labor and birth in a midwifery-led unit. With thanks to St George’s University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust for use of the image.

The same applies to homebirths where there would also be fewer drugs available to manage postpartum hemorrhage and there are minimal staff available to help in the case of an emergency. In midwife-led and homebirth settings it is usual for there to be more of a focus on the birthing environment, making it less clinical and more of a homely environment. This is achieved by using low lighting, LED candles, paintings, plants and reducing the amount of clinical equipment which can be seen. This approach can also be transferred to rooms in the obstetric-led unit and research has supported this less clinical environment by showing that it improves the experience of outcomes for mothers and neonates because a more relaxing environment has a relaxing effect, increasing oxytocin levels.12

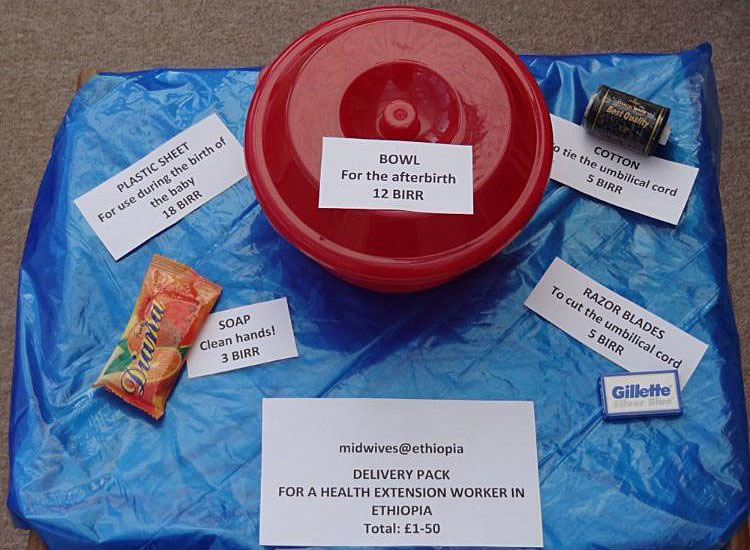

In less-developed countries much of this equipment is seen as a luxury and not essential because relatively less equipment is available in their healthcare facilities. Less-developed countries have a much higher rate of births outside of healthcare facilities due to issues with disrespectful care within them, the distance required to travel to get to a facility and the beliefs of women and those around them.5 There are many charities that provide training and the provision of essential equipment in these less-developed countries such as Midwives@Ethiopia.13 In these countries there is a greater emphasis on educating women in the safety of birthing within a healthcare facility rather than having a homebirth (the opposite to what research has shown to be safe within the developed world).13 Part of the reason for this is the availability of some essential equipment for labor and birth within these facilities which may not be available at a homebirth. Health extension workers (HEWs) have greatly influenced what equipment should be contained in the delivery packs in Ethiopia which are very similar to those used in other less-developed countries.13 Table 2 lists items deemed as essential equipment within these delivery kits.13

2

Essential equipment contained in delivery packs in developing countries.

Essential equipment | Use |

Plastic sheet | To keep the area clean and free from dirt |

Soap | To reduce the risk of infection by washing the mother |

Razor | To shave pubic hair for cleanliness |

Cotton tie | To tie the cord following birth |

Gloves | Personal protective equipment for the health workers. To reduce the risk of infection and spread of disease |

Misoprostol | A drug used for the management of postpartum hemorrhage |

Tranexamic acid | A drug used for the management of postpartum hemorrhage available in some less-developed countries. This is a recommendation from WHO |

8

Birthing kits used in Ethiopia as provided by Midwives@Ethiopia. Permission kindly given to use photo by Midwives@Ethiopia.

Organization of care for safe, woman-friendly birth is a complex matter that requires a number of components to enable it to be both safe and still support women’s choices and expectations. Care needs to be organized and planned from the start of pregnancy and be adapted according to women’s needs both physically and psychologically. Furthermore, the availability of equipment needs to be ensured to increase safety, but this will depend on the setting. However, having access to the best equipment that resources can provide will increase safety for both the mother and the neonate.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- Continuity of care models should be implemented wherever possible to improve maternal and neonatal outcomes.

- Multidisciplinary working should be achieved throughout maternity care including for labor and birth.

- The multidisciplinary teams should train together in their working environment, i.e. skills and drills on delivery suite/labor ward.

- Parents' birth choices should be listened to and plans of care should be created to ensure safety whilst supporting their wishes. Women have a right to a choice of place of birth, mode of birth and respectful maternity care.

- Ensure essential equipment is available in the birthing environment depending on the availability of resources.

- Ensure the birth environment is not clinical in its appearance and has a variety of alternative equipment available for mothers to use to enable them to keep mobile during labor and birth.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) of this chapter declare that they have no interests that conflict with the contents of the chapter.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

REFERENCES

World Health Organization (WHO). WHO recommendations: intrapartum care for a positive childbirth experience. Geneva, 2018. | |

Scarf VL, Rossiter C, Vedam S, et al. Maternal and perinatal outcomes by planned place of birth among women with low-risk pregnancies in high-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Midwifery 2018;62:240–255. doi: 1016/j.midw.2018.03.024. | |

Sandall J, Coxon K, Mackintosh N, et al. Relationships: the pathway to safe, high-quality maternity care Report from the Sheila Kitzinger symposium at Green Templeton College. Green Templeton College. Oxford: 2015. | |

Sandall J, Soltani H, Gates S, et al. Midwife-led continuity models versus other models of care for childbearing women. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev 2016;(4) Art No.:CD004667. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004667.pub5. | |

Miller S, Abalos E, Chamillard M, et al. Beyond too little, too late and too much, too soon: a pathway towards evidence-based, respectful maternity care worldwide. Lancet 2016;388(10056):2176–2192. doi: 10.1016/S0140–6736(16)31472–6. | |

National Maternity Review. Better Births: Improving outcomes of maternity services in England – A Five Year Forward View for maternity care. 2016 Feb 22 [cited 2018 May 29]. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/national-maternity-review-report.pdf. | |

Kings Fund. Safe Births: Everybody’s Business, 2008 Feb 29 [cited 2018 Jun 12] Available from: kingsfund.org.uk/publications. | |

Symons A. Risk and Choice in Maternity Care. London: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier, 2006;1–9. | |

Plested M, Walker S. Building confident ways of working together around higher-risk birth choices. MIDIRS 2014;5(9):13–16. | |

Birth Rights. Human Rights in Maternity Care, [cited 2018 May 22] 2017. Available from: http://www.birthrights.org.uk/library/factsheets/Human-Rights-in-Maternity-Care.pdf. | |

Council on Foreign Relations. The Global Human Rights Regime, [cited 2018 May 25] 2018. Available from: https://www.cfr.org/report/global-human-rights-regime. | |

Birthplace in England Collaborative Group. Perinatal and maternal outcomes by planned place of birth for healthy women with low risk pregnancies: the birthplace in England national prospective cohort study. BMJ 2011;343(d7400):1–13 doi: 10.1136/bmj.d7400 | |

Midwives@Ethiopia, [cited 2018 Jun 12] 2018. Available from: http://www.midwives-ethiopia.org.uk. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards programme CLICK HERE)