This chapter should be cited as follows:

De Seta F, MacNeil C, et al., Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.419903

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Gynecology Module

Volume 12

Infections in gynecology

Volume Editors:

Professor Francesco De Seta, Department of Medical, Surgical and Health Sciences, Institute for Maternal and Child Health, University of Trieste, IRCCS Burlo Garofolo, Trieste, Italy

Dr Pedro Vieira Baptista, Lower Genital Tract Unit, Centro Hospitalar de São João and Department of Gynecology-Obstetrics and Pediatrics, Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade do Porto, Portugal

Chapter

Candida Vulvovaginitis

First published: August 2023

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

INTRODUCTION

Candida albicans as well as non-albicans Candida species are of unquestioned clinical significance. Most authors will underscore the expansive significance of mycoses by asserting that most of the world’s population will have a fungal skin infection at some point in time, and although these are minor in most instances, severe systemic fungal infections are fatal approximately a million times per year.1 Another way to see the extensive reach of Candida spp. is by anatomic cataloging as in addition to skin, oral, gastrointestinal, bloodstream infections, and abscesses of various organs, including the eye and brain, cause significant morbidity world-wide. One may also note that most medical specialties whose diagnostic efforts require vigilance for fungal pathogens have keen interest in these organisms. The obstetrician–gynecologist has a particular focus on Candida infections as the vaginal mucosa is a common location of overgrowth of the organism. In fact, three quarters of all women will be affected by vaginal candidiasis at least once in their lifetimes and there may also be implications for pregnant women and neonates.2

During the past 7 decades, there have been numerous advances that have provided physicians and scientists new tools to continue to delve deeper into the host–microbe interactions involved with the genus Candida and with the species Candida albicans in particular.3

More specific to the obstetrician and gynecologist, the advent of the Human Microbiome Project led to important discoveries concerning the indigenous microbiome of the vagina, urinary tract, and gut and these have had profound influences on how vaginal infections are understood.4

In this chapter we do not propose to look in detail at the biology of Candida spp., but rather focus on the clinical aspects and treatment, keeping a clear understanding that current recommendations have been made based on the massive amount of information available. An excellent overview of the current state of understanding Candida spp. and candidiasis was published by d’Enfert et al. in 2021.5 First, C. albicans may transition from commensal to (opportunistic) pathogen, by mechanisms not fully understood. There are fascinating associations in these transitions, including pleiomorphic structure, adaptation to dynamic microenvironments, the white/opaque switching phenomenon, and biofilm formation.6,7 Second, there is a vast range and frequency of infections. Although great attention is paid to conditions where mortality occurs, the real story with Candida spp. is the great disease burden caused by its more frequent and less severe manifestations. Third, the fact that this organism has been studied perhaps almost as deeply as any other microbial pathogen and nevertheless it is still a pervasive clinical concern.

Against this backdrop, it should be encouraging for practicing physicians that efforts continue in order to try to better understand the host–microbe interactions, as well as the search for novel approaches for therapy.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

While it is true that fatal infections easily attract attention,8 the burden of disease for patients with vaginitis symptoms should not be minimized. Yearly, millions of women are affected with genitourinary symptoms due to candidiasis, resulting in significant distress, discomfort, loss of productivity, and heavy costs related with diagnosis and treatment. As cultures are not routinely used for the diagnosis of vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC), published reports are likely to underestimate its true prevalence. Adding to the direct burden of vaginal candidiasis, it can be added that it may be recrudescent, recurrent, or complicated by coinfections. In an internet survey of women recruited by response to a business card provided at a gynecology clinic, among 284 non-pregnant respondents, 78% reported having had VVC and 34% reported having recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis (RVVC).9

In a Greek cohort of women with vaginal symptoms it was found that 11.9% had VVC and 5.1% RVVC. The most common species involved were C. albicans (75%), followed by C. glabrata (13.6%).10 By comparison, in a study from Iran, C. albicans represented 67% of cases and C. glabrata 18.3%. Less commonly, they identified C. tropicalis (6.8%), C. krusei (5.8%), C. parapsillosis (1.6%) and C. guilliermondii (0.5%). They also reported that 10% had multiple isolates, being C. albicans with C. glabrata the most common association.11

As for other genital tract infections, a primary question for the patient is whether the infectious agent is transmissible through sexual contact. This question is largely obviated by the fact that C. albicans and other fungal species may belong to the indigenous microbiome and various authors have suggested that yeast vaginitis generally is due to organisms already present in the patients.12,13 The rate of vaginal colonization has been estimated to be around 15% in healthy non-pregnant women but is increased during pregnancy and with diabetes mellitus.14,15 Most older studies employed cultures to determine prevalence, which is subject to sampling error, dependent on abundance of organisms in the sample, and sometimes harmed by the previous use of antifungals.

While cultures retain its utility and are widely available to almost any clinician, molecular diagnostics and epidemiology have expanded the understanding of the scope of Candida spp. as part of the microbiomes of the skin, mouth, gastrointestinal tract, and urogenital tissues. One study on non-pregnant women and that included mycobiome evaluation of molecular sequences, showed that in 36.9% of cases the vaginal specimens had fungal elements and that the species diversity was greater than previously realized.16 This underscores the likelihood that molecular techniques will greatly alter our understanding of the prevalence of fungal components in the microbiome. Establishing the relative abundance of yeast in relation to bacterial elements is also within the scope of sequence-based taxonomy.

Another addition to this rapidly developing field is metabolomics and multi-omics studies. In 2019, the first metabolomic study of vaginal samples from healthy women as well as from women with bacterial vaginosis (BV), VVC, and chlamydial infection were submitted to proton-based nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy and determined that metabolic signatures of BV and VVC were distinct from healthy volunteers and certain metabolites, including trimethylamine oxide, threonine, and methanol, were relatively increased in VVC.17 The authors also posited that their data raised the possibility of a role of the gut microbiota in vaginal dysbiosis. This line of research is continuing to develop and more multi-omic studies in different populations, with and without pathology, are now available in the literature, emphasizing the importance of discovering which properties of the vaginal microenvironment are conducive to colonization and what ecologic changes result in symptomatic vaginitis.

The vagina represents a dynamic ecosystem and many of the studies have provided data from a sample at one point in time, though this is being addressed by current research.18 The squamous vaginal epithelium undergoes maturation under estrogen influence, glandular secretions, and exudation from the underlying tissue; the presence or absence of luminal phagocytic cells will differ from time to time and may also play a role.

Further, the mycobiome exists in the presence of a diversity of bacteria. Each microbial species has an individual repertoire of metabolic reactions to the available substrates, luminal fluids, and other microbial species. Finally, the beneficial immunologic influences of the eubiotic microbiome on maintaining a healthy balance of the diverse elements of the vagina is beginning to be understood. Additionally, the homeostasis of the microbiome may be challenged by external factors including menstruation, intercourse (protected or not), drugs,19 and even cigarette smoking.20 These will not be discussed in detail here, but for an excellent analysis of this topic, the authors recommend a recent review on this evolving and complex issue.16

It is reasonably well understood that most cases of yeast vaginitis are related to the population density or biomass of Candida spp. in the vagina21 though absolute numbers that indicate a pathologic condition are unknown. Also, other factors may attend. While a second occurrence of candidiasis occurs in 40–45% of women, complicated cases occur in 10–20% implying a more detailed diagnostic evaluation.22

Currently, it is appropriate to consider vaginal candidiasis as a sporadic endogenous infection that occurs when organisms belonging to the indigenous microbiome expand their biomass in absolute terms or in relationship with the co-colonizing bacteria. A common issue among fungi, as well as bacteria, is their ability to sense the population through quorum sensing.23 This ability is linked to additional processes relevant to pathogenesis; among these, biofilm production is a key point.7 Biofilms contribute to the survival of the organism by downshifting metabolism towards a quiescent, persistent state24 that favors survival during nutritional stress and makes the organism less susceptible to antimicrobial drugs. Biofilms have been studied extensively in relation to VVC and RVVC.25

C. albicans virulence is also regulated by its ability to undergo morphologic changes from blastospores to pseudo hyphae or hyphae as an adaptation to life within the human host. Hyphal forms may have a variety of mechanisms that abet invasion, including the ability to penetrate epithelial cells, resistance to phagocytosis and altered susceptibility to antifungal substances.26 Broadly applied, this information suggests that within the vaginal compartment, conditions that favor increase in biomass, transition to filamentous cellular morphology and biofilm development represent microenvironmental conditions that support sporadic or recurrent symptomatic vaginitis.

To summarize our current level of understanding of Candida spp. epidemiology as it relates to the biology of the organism and natural history in human hosts, it must be kept in mind that C. albicans and C. glabrata, as well as other fungal species, routinely colonize the human host as commensals. Commensal colonization may involve one or more epithelial sites and colonization may be continuous, discontinuous, and may change from one site to another.

Severe vaginitis symptoms are associated with higher fungal burdens and suggest a loose dose-response relationship between microbial biomass and symptoms.

C. albicans has an almost unique ability to exhibit alternate morphologies of blastospores, hyphae or pseudohyphae in vivo, which is associated with its pathogenic state. Virulence is multifaceted in vaginal yeast infections, but biofilm has a recognized importance. Immunologic factors may influence the likelihood of RVVC.

Therapeutic approaches generally are directed at reducing the fungal burden, but contemporary interest is turning to restoring the microbial milieu to one which is not conducive to yeast proliferation.

In the remainder of this chapter, the clinical approach to diagnosis, pharmaceutical and non-drug treatments will represent the practical outgrowth of the above-described fundamental aspects of Candida spp. biology and interaction with colonized individuals.

CLINICAL FINDINGS

The most common presenting symptoms in patients meeting diagnostic criteria for Candida spp. vulvovaginitis are variable intensity itching and irritation. With increasing intensity, itch is often perceived as burning, while as intensity decreases it is perceived as soreness. These symptoms are often perceived externally at the vulva, internally within the vagina, or both. Itching/burning is typically – but not always – accompanied by heterogenous non-odorous white to yellow vaginal discharge, often described by patients as “cottage cheese”, though each of these signs may present alone.15

While itching, irritation, and discharge are widely recognized as VVC chief complaints it must be kept in mind that these findings are non-specific and can be found in several other disorders, such as trichomoniasis and vulvar dermatitis/vulvitis. Physical exam signs of inflammation such as vulvar and/or vaginal enanthema, edema, and fissuring increase the likelihood of a correct diagnosis: indeed, when inflammation is found in association with itching soreness the likelihood ratio of Candida spp. increases to 5.1.15 Nevertheless, these signs and symptoms have proven inadequate in arriving at the correct diagnosis. When Schwiertz et al. in 2006 objectively tested for evidence of yeast in patients with these findings, the rate of misdiagnosis for VVC was 77%. These findings point to the importance of objective evidence of Candida spp. micro-organisms in supporting the diagnosis.16

The wide variability of symptoms and signs found in patients with uncomplicated vulvovaginitis extends to complicated VVC.9 Many patients with C. glabrata and C. parapsilosis VVC report little or no itching, irritation, or discharge. Subjects afflicted with RVVC can often be found to have a decreased number of yeast and milder changes on exam but more intense itching and burning,17 further supporting the importance of objective testing.

DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

In the absence of symptoms and signs, no testing for yeast is warranted. Yeast identified, for example, by cervical cytology in an asymptomatic patient do not warrant further diagnostic testing (or treatment).

Saline and KOH wet prep microscopy should be performed in all symptomatic females.15,27 Reports describing the errors in cases of misdiagnosis often cite failure to perform wet prep microscopy as the most frequently found reason for the error. Clinician inexperience and resultant discomfort with performance of the procedure is one contributor to decreasing frequency of performance of office microscopy.16 Moreover, performance of wet preps and information garnered can be quite variable: false positive and false negative determinations are not trivial thus local clinic standards must be established and maintained through regular competency review and testing.19

The wet prep sample should be collected with a swab from the vaginal walls of the mid-to-lower vagina to avoid collecting cervical mucus, and tested for pH. Sampling the vaginal reservoir is important, even when symptoms and signs are only found externally at the vulva.28 Testing vaginal pH is recommended and can aid in broadening the differential diagnosis: although VVC is typically associated with a pH below 4.7 it is possible to find Candida spp. in patients with pH above 4.7.29 The sample should be mixed with normal saline and, separately, mixed 1 : 1 with 10% KOH. The KOH portion of the sample should be tested for an amine/fishy odor suggestive of bacterial vaginosis. The slides should be viewed at low (100×) power and intermediate (400×) power. It is helpful to first examine the saline slide to screen for trichomonas and evaluate the degree of inflammation by comparing white blood cell number with the number of epithelial cells (>1 : 1 indicates an inflammatory condition). Next, examination of the KOH slide to detect hyphal or blastospore yeast forms can be performed.27,30 The need for the use of KOH can usually be overcome if phase contrast microscopy is used.

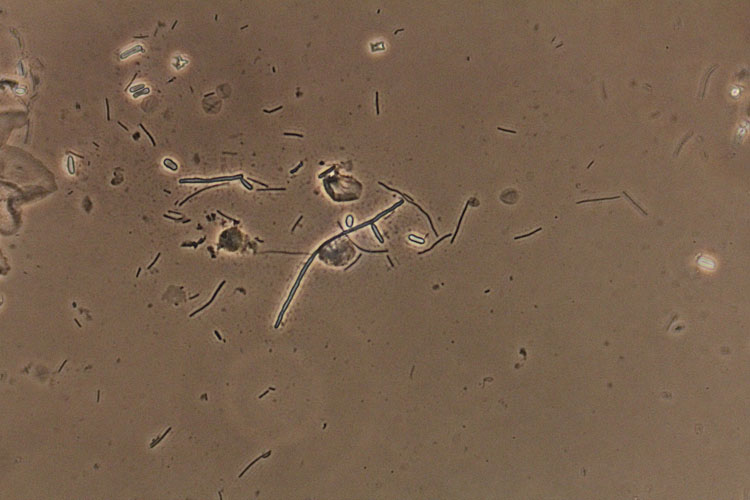

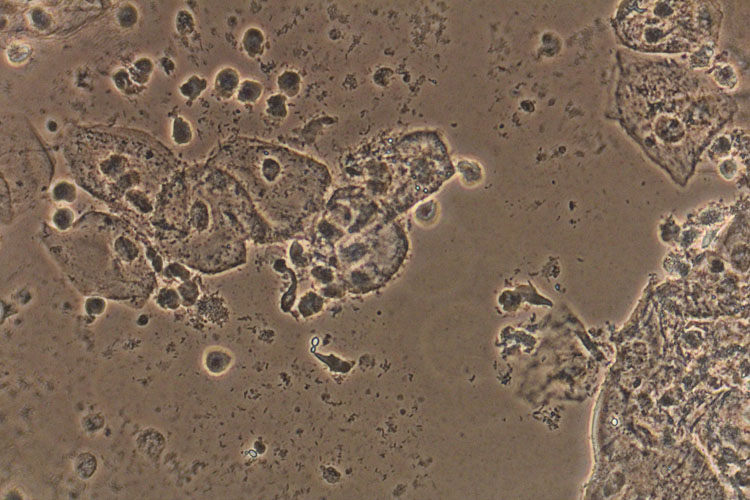

A patient with a wet prep finding of hyphae and pseudohyphae (Figures 1 and 2), indicative of active growth of C. albicans, does not require additional testing. Only in the instance of persistent infection should yeast culture and susceptibility testing be considered.

1

Blastospores and hyphae, suggestive of Candida albicans (confirmed by culture). Phase contrast wet mount microscopy (400×).

2

Blastopores and inflammation in a case of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. Phase contrast wet mount microscopy (400×).

In symptomatic patients with negative wet prep microscopy yeast, culture should be performed on Saboraud’s agar, Chromagar, or in Nickerson media. Culture also yields valuable information on species other than C. albicans, especially in cases of RVVC where non-albicans species are more frequently encountered.20,28

Nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT) have come into use due, in part, to ease of use in a busy practice.21 NAAT typically – with individual test variation – provide combined analysis for BV, C. albicans and a few non-albicans Candida, and Trichomonas vaginalis. The high sensitivity of NAAT is an advantage for detecting trichomonas, an alternative cause of inflammation in the differential. Sensitivity is valuable in detecting a very small Candida spp. load in patients with RVVC who have become hypersensitive to a small number of yeast.17 Unlike wet prep microscopy, NAAT cannot provide information on inflammation. In many settings NAAT cost exceeds $600.00 USD, and results are not immediately available. We recommend wet prep microscopy first in every case of suspected VVC.

Differential diagnoses

In patients with vulvar itching and burning, and repeated negative yeast culture or NAAT, an irritant or allergic contact dermatitis of the vulva, hypersensitivity reaction, cytolytic vaginosis, neurodermatitis, or lichenoid dermatoses should be considered.29 In some cases a biopsy can be considered when the diagnosis is uncertain.22 In similar patients with an elevated pH and in whom saline wet prep identifies abundant white blood cells, trichomoniasis should be ruled out by NAAT (saline microscopy sensitivity is less than 50%) and desquamative inflammatory vaginitis (DIV) should be considered.23

Treatment

Treatment of VVC is indicated for relief of symptoms. It is important to note that up to 20% of women harboring Candida spp. generally, and a much larger proportion of those harboring C. glabrata and C. parapsilosis, are asymptomatic and should not be treated.

Uncomplicated VVC is usually treated effectively with azole antifungal creams, ovules or a single oral fluconazole 150 mg tablet, achieving 85% symptom resolution and negative culture with any of these modalities.24,25 Because symptom resolution rates are approximately equal for each of these medications, the choice is patient and provider dependent. Most patients prefer a single fluconazole tablet over nightly application of vaginal creams, and many clinicians prefer to avoid vaginal creams because of sporadic reports of vaginal burning in response to various ingredients in the creams.

Alternatives to azole antifungals

A small minority of patients will be found to be intolerant of or allergic to fluconazole. Gastrointestinal intolerance (nausea) is improved by taking fluconazole with food; if persistent, an alternative should be selected. Allergy symptoms may range from a rash to angioedema. In such cases it is difficult to know if the reaction is to the azole component and therefore the degree of cross-reactivity to alternative azoles, such as itraconazole and ketoconazole, is uncertain until consultation with an allergist can be obtained. In these cases, a low-dose vaginal azole (i.e., clotrimazole 1% vaginal cream nightly for 1 week), which is usually well tolerated, can be an option.25 Another option is to avoid any azole-class medication and administer ibrexafungerp (Brexafemme), a first-in-class glucan synthase inhibitor.31 The recommended 1-day treatment is two tablets (300 mg) and a repeated two tablets 12 hours later, for a total of 600 mg in 1 day. Like fluconazole, ibrexafungerp must not be taken while pregnant.

A minority of patients will be found to respond poorly to fluconazole. It is important to note that the patient’s symptoms, which seem to be unresponsive to fluconazole, may seem not to be responding because the itching and burning are caused by another condition such as trichomoniasis, DIV, or contact dermatitis; in unresponsive cases it is important to first re-establish the diagnosis, including repeat fungal culture with antifungal susceptibility testing. Alternative treatments to fluconazole, with direction from susceptibility test findings, are described above.

Complicated vulvovaginal candidiasis

More than 10% of patients present with complicated vulvovaginal symptoms. Complicated VVC include those with more intense (severe) itching/burning, frequent recurrences (RVVC), and symptoms due to a non-albicans species. These are more often found in immunocompromised patients and in those with diabetes. In each of these complications the challenge is to more effectively/completely reduce the population of yeast. Some experts consider RVVC to be divisible into etiologic categories: primary RVVC that arises spontaneously with no predisposing biomedical conditions associated with onset or recurrences; and secondary RVVC associated with immune compromise, uncontrolled diabetes, frequent/prolonged antibiotic administration or some other factor such as hypersensitivity to Candida spp. antigens. Factors that underly secondary RVVC should be optimized as much as possible: control hyperglycemia; discontinue sodium-glucose cotransportor-2 inhibitors (which have been associated with frequent recurrences) for alternative hypoglycemics, minimize antibiotic use, and reduce systemic steroid dose.32 Before considering treatment selection it is essential, as it is in uncomplicated VVC, that the clinician is confident the symptoms are caused by Candida by repeating fungal culture or NAAT testing. In the case of complicated VVC, because the likelihood of non-albicans Candida and fluconazole-resistant Candida spp. is greater, culture positivity is essential before formulating a treatment plan. Growth in culture also provides the opportunity to test antifungal sensitivities if treatment fails, though the benefit of such testing has been questioned. Patients experiencing severe symptoms who are culture positive with C. albicans benefit from extended courses of the same azole antifungals that are used to treat uncomplicated VVC. Fluconazole 150 to 200 mg taken every 72 hours for three to four tablets depending on severity is recommended.9 In non-pregnant patients who experience side effects or are allergic to fluconazole, ibrexafungerp 300 mg (two tabs) repeated 12 hours is an option. Because of ibrexafungerp teratogenicity the clinician must be certain that secure contraceptive practices are in place or limit use to postmenopausal patients.33 Clotrimazole 1% vaginal cream inserted nightly for 2 weeks is an alternative recommendation for patients that are intolerant of fluconazole and who are unable to acquire ibrexafungerp or are pregnant. Oteseconazole (previously VT-1161) is a new fungal CYP51-targeted drug, that as shown efficacy against C. albicans and non-albicans species.34 The proposed scheme is 600 mg on day 1, followed by 450 mg on day 2 and then, starting on day 14, 150 mg for 11 weeks. The relapse rate by week 50 was of only 5.1% and the drug profile in terms of adverse effects was similar to fluconazole.35 An alternative scheme, starting with fluconazole in the induction phase is also possible.36 Nevertheless, its use is contraindicated in women with reproductive potential, and in those pregnant or breastfeeding due to embryo-fetal toxicity (ocular abnormalities) in noticed in animal studies. The drug exposure window is of about 690 days.36

For patients with intense external burning, application of a mild potency steroid such as triamcinalone 0.1% or betamethasone 0.1% in ointment form, applied once or twice a day until burning is quiet can be helpful.

RVVC, whether primary or secondary, should be treated with antifungals used for VVC beginning with an induction phase for 7 to 14 days, and then treatment continued at a lower dose in a maintenance phase for at least 6 months. A frequently cited regimen is fluconazole 150 mg taken every 72 hours for three doses and continued 150 mg each week for 6 months.37 The Infectious Disease Society of America recommends the induction phase extends to 10 to 14 days and then once-weekly fluconazole 150 mg maintenance continues for 6 months38 European experts recommend a variations of the US regimen: the ReCiDiF regimen, recommended by 2018 European IUSTI/WHO guidelines specifies fluconazole 150 to 200 mg per day for 3 days, then 100 to 200 mg per week for 2 months and then 200 mg bi-weekly for 4 months and 200 mg per month for 6 additional months, total 1 year.31

Fluconazole resistance, once very rare, may be increasing with the increasing use of maintenance fluconazole.39 Often, in cases of suspected loss of susceptibility, the isolate is dose-susceptible, and symptoms can be controlled at an increased dose. Sobel recommends testing drug minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) in cases of refractory vulvovaginitis with persistently positive C. albicans cultures, and for isolates with a MIC between 2 and 4, administering fluconazole 200 mg on 2 days of the week for 6 months.40 In cases of pan-azole resistance, vaginally administered boric acid 600 mg, nystatin 100,000 U, amphotericin B and flucytosine vaginal suppositories nightly for 2 weeks are options. It bears repeating that, taken orally, boric acid has been reported to be fatal and should only be administered vaginally.

Non-albicans Candida

C. glabrata, C. krusei, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae are associated with less severe symptoms and are intrinsically less sensitive to fluconazole.41,42,43 C. krusei often remains sensitive to azole vaginal creams. For symptomatic patients who are culture positive for C. glabrata, initial treatment with vaginal boric acid suppositories or nystatin suppositories have been reported to result in a 70% cure rate. Nystatin 100,000 U suppositories inserted nightly for 3–4 weeks, or vaginal boric acid administered as a 600 mg vaginal suppository or capsule nightly for 2–3 weeks are recommended, selection based on tolerability and availability. Boric acid is sometimes irritating, and because it has been reported to be embryotoxic and is associated with toxicity and death if ingested orally, it is not available in some countries. Nystatin suppositories are not commercially available in some countries and must be prepared by a compounding pharmacy. Amphotericin B 50 mg compounded as a suppository can also be inserted vaginally nightly for 2 weeks.44 In patients in whom nystatin, boric acid or amphotericin B are ineffective at symptom reduction, there is a case report of treatment with compounded flucytosine 1 g and amphotericin B 100 mg in an 8 g suppository nightly for 2 weeks with successful symptom control.45

Ibrexafungerp has reported in vitro activity against many non-albicans species, including C. glabrata. Clinical activity in symptomatic patients harboring C. glabrata has recently been reported.46 For cases of RVVC due to non-albicans species, vaginal boric acid and nystatin can be continued, following a 2–4-week induction course, at 2 nights per week for 6 months at which time it is reasonable to attempt discontinuation. There are limited outcomes data on the use of maintenance nystatin; unfortunately, there are no data on the long-term use of boric acid suppositories.

Special populations

Pregnant patients

VVC is commonly encountered in pregnant women.12,47 Fluconazole has been associated with increased incidence of cardiac, facial and musculoskeletal birth defects and must not be prescribed to pregnant patients. The first-line treatment is clotrimazole 1% vaginal cream nightly for 2 weeks. An alternative treatment is nystatin 100,000 U pessary or if not available compounded in a suppository inserted nightly for 2 weeks.

Children

Complaints of vulvar itch, erythematous rash and discharge, often mucoid, are commonly encountered in healthy toilet-trained prepubertal girls. Yeast, which can be found in 3% of asymptomatic carriers, is rarely the causative factor; a high rate of overtreatment with antifungals has been documented.15 When these symptoms present, contact dermatitis, group A streptococcus (S. pyogenes), Staphylococcus aureus, enteric bacteria and pinworm should be ruled out. Overtreatment with antifungal agents should be avoided.33 In the setting of diapers, mycotic infections appear as beefy red patches with satellite macules or pustules and should be treated empirically with azole creams. In the setting of recent antibiotic administration, yeast can arise secondarily and warrant empiric treatment. It is helpful when uncertain to culture for yeast in pre-pubertal children with irritative vulvovaginal symptoms because the rate of true Candida spp. infections, though not clearly established, is considered extremely low due to the absence of estrogen.33 Adolescents with VVC are treated following the guidelines outlined above for adults. For those weighing less than 50 kg, single fluconazole doses of 2–3 mg/Kg are effective in uncomplicated VVC, for severe symptoms 2–3 mg/Kg repeated in 72 hours, and for cases with three or more recurrences in 1 year 2–3 mg/Kg every 72 hours for 7 to 10 days and continued 2–3 mg/Kg each week for 6 months.

Immunocompromised host

Patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy or suffering immune deficiencies are more often colonized with Candida spp.3 In this broad population fluconazole is generally well tolerated and effective in the short term.48,49,50 These patients often benefit from longer duration treatment. In the case of symptomatic RVVC in an immunocompromised patient treatment may need to extend well past the 6 months that are typically recommended.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- Candida albicans and glabrata, as well as other fungal species, routinely colonize the human host.

- Commensal colonization may involve one or more epithelial sites and colonization may be continuous, discontinuous, and may change from one colonized site to another.

- Severe vaginitis symptoms are associated with higher fungal burden and suggest a loose dose-response relationship between microbial biomass and symptoms.

- Candida albicans is generally the most common cause of fungal vaginitis, followed by glabrata, which is refractory to triazoles, and these species may occur separately, together or in concert with other species.

- Virulence is multifaceted in vaginal yeast infections, but biofilm formation has a recognized importance.

- Immunologic factors may influence the likelihood of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis (RVVC).

- Therapeutic approaches generally are directed at reducing the fungal burden, with topical or oral azole.

- Recurrent forms of VVC request maintenance treatment for 6 months.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) of this chapter declare that they have no interests that conflict with the contents of the chapter.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

REFERENCES

Brown GD, Denning DW, Gow NA, et al. Hidden killers: human fungal infections. Sci Transl Med 2012;4(165):165rv13. | |

Gonçalves B, Ferreira C, Alves CT, et al. Vulvovaginal candidiasis: Epidemiology, microbiology and risk factors. Crit Rev Microbiol 2016;42(6):905–27. | |

Sobel JD. Vulvovaginal candidiasis: a comparison of HIV-positive and -negative women. Int J STD AIDS 2002;13(6):358–62. | |

Willems HME, Ahmed SS, Liu J, et al. Vulvovaginal Candidiasis: A Current Understanding and Burning Questions. J Fungi (Basel) 2020;6(1). | |

d'Enfert C, Kaune AK, Alaban LR, et al. The impact of the Fungus-Host-Microbiota interplay upon Candida albicans infections: current knowledge and new perspectives. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2021;45(3). | |

Calderone RA, Fonzi WA. Virulence factors of Candida albicans. Trends Microbiol 2001;9(7):327–35. | |

Pereira R, Dos Santos Fontenelle RO, de Brito EHS, et al. Biofilm of Candida albicans: formation, regulation and resistance. J Appl Microbiol 2021;131(1):11–22. | |

Bilal H, Shafiq M, Hou B, et al. Distribution and antifungal susceptibility pattern of Candida species from mainland China: A systematic analysis. Virulence 2022;13(1):1573–89. | |

Yano J, Sobel JD, Nyirjesy P, et al. Current patient perspectives of vulvovaginal candidiasis: incidence, symptoms, management and post-treatment outcomes. BMC Womens Health 2019;19(1):48. | |

Maraki S, Mavromanolaki VE, Stafylaki D, et al. Epidemiology and antifungal susceptibility patterns of Candida isolates from Greek women with vulvovaginal candidiasis. Mycoses 2019;62(8):692–7. | |

Mahmoudi Rad M, Zafarghandi S, Abbasabadi B, et al. The epidemiology of Candida species associated with vulvovaginal candidiasis in an Iranian patient population. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2011;155(2):199–203. | |

Glover DD, Larsen B. Longitudinal investigation of candida vaginitis in pregnancy: role of superimposed antibiotic use. Obstet Gynecol 1998;91(1):115–8. | |

Daniels W, Glover DD, Essmann M, et al. Candidiasis during pregnancy may result from isogenic commensal strains. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 2001;9(2):65–73. | |

Gunther LS, Martins HP, Gimenes F, et al. Prevalence of Candida albicans and non-albicans isolates from vaginal secretions: comparative evaluation of colonization, vaginal candidiasis and recurrent vaginal candidiasis in diabetic and non-diabetic women. Sao Paulo Med J 2014;132(2):116–20. | |

Anderson MR, Klink K, Cohrssen A. Evaluation of vaginal complaints. JAMA 2004;291(11):1368–79. | |

Schwiertz A, Taras D, Rusch K, et al. Throwing the dice for the diagnosis of vaginal complaints? Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 2006;5:4. | |

Fidel PL Jr. History and update on host defense against vaginal candidiasis. Am J Reprod Immunol 2007;57(1):2–12. | |

Donders GG, Sobel JD. Candida vulvovaginitis: A store with a buttery and a show window. Mycoses 2017;60(2):70–2. | |

Donders GG, Marconi C, Bellen G, et al. Effect of short training on vaginal fluid microscopy (wet mount) learning. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2015;19(2):165–9. | |

Sobel JD, Sobel R. Current treatment options for vulvovaginal candidiasis caused by azole-resistant Candida species. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2018;19(9):971–7. | |

Danby CS, Althouse AD, Hillier SL, et al. Nucleic Acid Amplification Testing Compared With Cultures, Gram Stain, and Microscopy in the Diagnosis of Vaginitis. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2021;25(1):76–80. | |

Mauskar MM, Marathe K, Venkatesan A, et al. Vulvar diseases: Approach to the patient. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020;82(6):1277–84. | |

Reichman O, Sobel J. Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2014;28(7):1042–50. | |

Frey Tirri B. Antimicrobial topical agents used in the vagina. Curr Probl Dermatol 2011;40:36–47. | |

Sobel JD, Brooker D, Stein GE, et al. Single oral dose fluconazole compared with conventional clotrimazole topical therapy of Candida vaginitis. Fluconazole Vaginitis Study Group. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1995;172(4 Pt 1):1263–8. | |

Schwebke JR, Sobel R, Gersten JK, et al. Ibrexafungerp Versus Placebo for Vulvovaginal Candidiasis Treatment: A Phase 3, Randomized, Controlled Superiority Trial (VANISH 303). Clin Infect Dis 2022;74(11):1979–85. | |

Vieira-Baptista P, Grincevičienė Š, Oliveira C, et al. The International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease Vaginal Wet Mount Microscopy Guidelines: How to Perform, Applications, and Interpretation. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2021;25(2):172–80. | |

Sobel JD, Akins R. Determining Susceptibility in Candida Vaginal Isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2022;66(6):e0236621. | |

Vieira-Baptista P, Stockdale CK, Sobel J, et al. International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease Recommendations for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Vaginitis. International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease ed.; Admedic: Lisbon, 2023:195. | |

Kennedy MA, Sobel JD. Vulvovaginal Candidiasis Caused by Non-albicans Candida Species: New Insights. Curr Infect Dis Rep 2010;12(6):465–70. | |

Donders G, Bellen G, Byttebier G, et al. Individualized decreasing-dose maintenance fluconazole regimen for recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis (ReCiDiF trial). Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008;199(6):613.e1–9. | |

Nyirjesy P, Sobel JD, Fung A, et al. Genital mycotic infections with canagliflozin, a sodium glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor, in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a pooled analysis of clinical studies. Curr Med Res Opin 2014;30(6):1109–19. | |

Alaniz VI, Kobernik EK, George JS, et al. Comparison of Short-Duration and Chronic Premenarchal Vulvar Complaints. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2021;34(2):130–4. | |

Sobel J, Donders G, Degenhardt T, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Oteseconazole in Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis. NEJM Evid 2022;1(8). | |

Martens MG, Maximos B, Degenhardt T, et al. Phase 3 study evaluating the safety and efficacy of oteseconazole in the treatment of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis and acute vulvovaginal candidiasis infections. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2022;227(6):880.e1–11. | |

FDA VIVJOATM (oteseconazole). https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/215888s000lbl.pdf. | |

Sobel JD, Wiesenfeld HC, Martens M, et al. Maintenance fluconazole therapy for recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. N Engl J Med 2004;351(9):876–83. | |

Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes DR, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Candidiasis: 2016 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2016;62(4):e1–50. | |

Makanjuola O, Bongomin F, Fayemiwo SA. An Update on the Roles of Non-albicans Candida Species in Vulvovaginitis. J Fungi (Basel) 2018;4(4). | |

Sobel JD. Recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016;214(1):15–21. | |

Singh DP, Kumar Verma R, Sarswat S, et al. Non-Candida albicans Candida species: virulence factors and species identification in India. Curr Med Mycol 2021;7(2):8–13. | |

Powell AM, Gracely E, Nyirjesy P. Non-albicans Candida Vulvovaginitis: Treatment Experience at a Tertiary Care Vaginitis Center. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2016;20(1):85–9. | |

Boyd Tressler A, Markwei M, Fortin C, et al. Risks for Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis Caused by Non-Albicans Candida Versus Candida Albicans. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2021;30(11):1588–96. | |

Phillips AJ. Treatment of non-albicans Candida vaginitis with amphotericin B vaginal suppositories. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005;192(6):2009–12; discussion 2012–3. | |

White DJ, Habib AR, Vanthuyne A, et al. Combined topical flucytosine and amphotericin B for refractory vaginal Candida glabrata infections. Sex Transm Infect 2001;77(3):212–3. | |

Goje O, Sobel R, Nyirjesy P, et al. Oral Ibrexafungerp for Vulvovaginal Candidiasis Treatment: An Analysis of VANISH 303 and VANISH 306. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2023;32(2):178–86. | |

Patel MA, Aliporewala VM, Patel DA. Common Antifungal Drugs in Pregnancy: Risks and Precautions. J Obstet Gynaecol India 2021;71(6):577–82. | |

Nyirjesy P, Brookhart C, Lazenby G, et al. Vulvovaginal Candidiasis: A Review of the Evidence for the 2021 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention of Sexually Transmitted Infections Treatment Guidelines. Clin Infect Dis 2022;74(Suppl_2):S162–8. | |

Ray A, Ray S, George AT, et al. Interventions for prevention and treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis in women with HIV infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;(8):Cd008739. | |

Donders G, Sziller IO, Paavonen J, et al. Management of recurrent vulvovaginal candidosis: Narrative review of the literature and European expert panel opinion. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2022;12:934353. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards programme CLICK HERE)