This chapter should be cited as follows:

Edwards G, Marshall J, et al., Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.416233

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Obstetrics Module

Volume 15

The puerperium

Volume Editors:

Dr Kate Lightly, University of Liverpool, UK

Professor Andrew Weeks, University of Liverpool, UK

Chapter

Global Aspects of Breastfeeding

First published: February 2021

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

INTRODUCTION

Breastfeeding and infant deaths

Exclusive breastfeeding is defined as no other food or drink, not even water, except breastmilk for 6 months of life.1 The evidence is now overwhelming to show that breastfeeding saves lives, particularly in babies born in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC).2,3

Early initiation of breastfeeding in the golden hour after birth is crucial. Breastfeeding immediately after birth has been shown to increase the duration of breastfeeding and protect against gastrointestinal infections and malnutrition globally. Exclusive breastfeeding has also been linked to higher IQs and subsequently higher earning potential in children and a reduced risk of breast cancer in women who have breast fed.2,4 Mixed feeding and artificial feeding leaves infants at a greater risk of morbidity and mortality from infection.

If efforts were made to increase breastfeeding rates globally to reach universal levels, it would be the most effective way to ensure child health and survival and could potentially save around 820,000 infant lives per year. Presently, less than half of babies under 6 months of age are exclusively breastfed.3 Currently, there is wide variation in exclusive global breastfeeding rates from 3% in St Lucia to 87% in Rwanda and much work needs to be done, particularly in LMICs where the exclusive breastfeeding rate stands at 40%.5

HOW BREASTFEEDING WORKS: ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY OF LACTATION

Breast changes during pregnancy

Breast tissue matures during pregnancy, increases considerably in size by 22 weeks' gestation and during the last trimester, fully maturing once lactation is established. Growth of the glandular tissues occurs in response to hormones such as estrogen, progesterone and prolactin and a range of growth factors. Blood flow to the breasts increases considerably during pregnancy raising metabolic activity and the temperature of the breast.6 This is maintained throughout lactation and can help to maintain the baby’s temperature when held skin to skin.

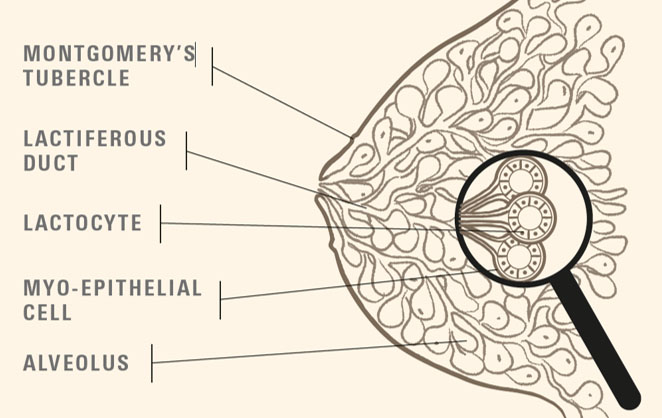

Anatomy of the breast

Externally, the size, shape and colour of women’s nipples and areola vary considerably. Within the areola there are sebaceous glands called Montgomery’s tubercles that secrete an oily substance which lubricates the nipple, protects against infection and may play a role in guiding the infant to the breast by producing a scent.7

The lactating breast is made up of glandular and adipose tissue supported by a network of connective tissue called Coopers ligaments.7 An ultrasound study of lactating breasts has shown that the proportion of glandular to adipose tissue varies greatly among women but has not been linked to women’s ability to produce milk.8,6

Glandular tissue within the breast is arranged in lobules that are made up alveoli (Figure 1). Each alveoli is lined with a single layer of lactocytes (milk producing cells) that are surrounded by myoepithelial cells. Milk is secreted into the lumen of the alveoli by lactocytes and this is ejected into the milk ducts when the myoepithelial cells contract in response to the action of the hormone oxytocin. These drain into fewer ducts of increasing diameter until milk is released at an opening at the end of the nipple. Ultrasound studies have demonstrated that the number of ducts varies, that there are many branches of the ducts close to the nipple, and that there are no sinuses located behind the areola as was previously thought.7,8 It is important for mothers to understand that breasts are not ‘containers’ of milk, but that the process of breastmilk production is ongoing, although the amount varies across each feed and throughout each day.

1

Anatomy of the breast. Reproduced with kind permission from UNICEF UK https://www.unicef.org.uk/babyfriendly/.

Physiology of lactation

There are two main hormones that are important in relation to maintenance of breastfeeding – prolactin and oxytocin. Prolactin is stimulated by suckling and nipple stimulation and is responsible for breastmilk production. It is secreted by the anterior pituitary gland into the blood stream and acts on receptor sites of lactocytes to stimulate milk production. This occurs systemically, works on both breasts and levels peak around 40–45 minutes after stimulation. Therefore, feeding now stimulates supply for the next feed. Oxytocin is secreted from the posterior pituitary gland and is responsible for milk ‘let down’. It acts on the myoepithelial cells surrounding the alveoli to move milk through the ductal system towards the nipple. Ducts are shortened and duct diameter increases facilitating milk transfer. Oxytocin is stimulated by the mother seeing, touching, hearing and smelling her baby, as well as suckling. Levels of oxytocin rise within 1 minute of stimulation, but can be inhibited by the stress response – usually temporarily. As breastfeeding becomes established oxytocin can be secreted by other stimuli such as thinking about feeding or hearing a child cry. In addition to the direct effect on breastfeeding, oxytocin enhances feelings of well-being and increases interaction between mother and baby.9

When a mother’s breasts become full, breastmilk production is regulated by a whey protein present within the milk called feedback inhibitor of lactation (FIL). This is produced by lactocytes in response to distention of the alveoli and exerts local control within each breast. As breastmilk is removed from the breast, concentration of the whey protein diminishes and breastmilk synthesis continues.10

Babies are born with three main reflexes that are crucial for feeding. These are:

- Rooting reflex – is elicited when something touches the baby’s cheek, they turn their head and open their mouth, bring their tongue forward and down.

- Sucking reflex – is stimulated when something touches the baby’s palate, they suck to draw it into their mouth.

- Swallowing reflex – is elicited when the baby’s mouth fills with milk, they raise the jaw to swallow.

The sucking and swallowing reflexes are coordinated for a baby to feed and in newborns the epiglottis and soft palate touch at rest providing good airway protection.

SUPPORTING WOMEN TO INITIATE AND CONTINUE BREASTFEEDING

Breastfeeding is a global public health issue and is one of the most effective ways to improve maternal and infant health. Globally, when babies are breastfed suboptimally they are almost 12% more likely to die from infections and illnesses.11 Estimates from systematic reviews suggest that increased breastfeeding would prevent around half of the episodes of diarrhea and a third of respiratory infections.3 Breastfeeding also protects against conditions in later life such as obesity, high blood pressure and type 2 diabetes.12 Babies in developing countries are at higher risk of illness and death if they are not breastfed due to lack of access to clean water and sanitation. For women, breastfeeding protects against breast cancer and it has been estimated that if breastfeeding was scaled up to almost be universal then 20,000 breast cancer deaths could be prevented.3 Mothers who do not breastfeed are also at increased risk of ovarian cancer, obesity and type 2 diabetes and, additionally, breastfeeding exclusively improves birth spacing.13,3 Despite the many ways in which breastfeeding improves health of both mothers and babies, less than half are breastfeed as exclusively and for as long as recommended and rates vary greatly across and within countries globally.3 Most women are physically able to breastfeed, although in many areas of the world mothers are constrained by cultural expectations of mothering, including feeding, and it is common for women to believe they do not have sufficient milk to feed their baby. However, providing support to breastfeeding mothers is effective in helping mothers to continue.14

It is important to encourage mothers to begin to develop a relationship with their baby during pregnancy as there is increasing evidence of the central role of this for future emotional health and well-being, not only for this child, but also across generations.15 Recent advances in epigenetics and neuroscience underline the importance of positive nurturing environments, reduced stress both during pregnancy and early after birth encourages expression of beneficial genetic markers16,17 and enhances brain development.18 This can be achieved through conversations with pregnant women encouraging them to talk and sing to the baby in utero and to discuss their hopes in relation to motherhood and infant feeding. These should take account of her cultural and social context. It may be challenging for mothers and families experiencing adverse conditions such as poverty, displacement or violence to provide nurturing care for their infants,16 but nurture has been described as the ‘anchor’ within the broad range of possible interventions to improve childhood development outcomes.18

Skin to skin after birth: a good start to breastfeeding

The first hour after birth is a crucial period for both mother and baby, and skin to skin contact during this time has a range of important benefits, including increased likelihood of breastfeeding successfully at the first feed and breastfeeding for longer.19,20 Skin to skin contact between mother and baby encourages oxytocin production which enhances the mother’s protective instincts and feeling of love. Skin contact is calming for the newborn and elicits a sequence of instinctive behaviors ending with familiarization of the breast and breastfeeding.21,22

See USEFUL LINKS for a Global Health video on skin to skin.

Recognising feeding cues

Women should be encouraged to keep their baby close to them and to observe their baby’s behavior. This will ensure they become familiar with feeding cues that will encourage responsive breastfeeding, such as noticing when the baby starts to awaken, making mouth movements, licking their lips, rooting and putting their hands to their mouth. Once a baby begins to cry, breastfeeding becomes more difficult to initiate, so mothers should be encouraged to begin to feed when they see these feeding cues.

Skills to support breastfeeding

Learning to breastfeed is a skill that a mother and baby must learn together and it is important for a baby to feed effectively to maintain the mother’s milk supply. Providing women with support enables them to breastfeed for longer and more exclusively.14 Support is complex and can take many forms such as emotional, informational and practical. In terms of practical support, it is important for women to recognise the signs of effective attachment – that is the process of the baby taking the breast into their mouth (Table 1) and to observe the baby’s suckling pattern and swallowing. See USEFUL LINKS for a good video of effective attachment.

1

Signs of good attachment at the breast. Adapted from https://www.breastfeedingnetwork.org.uk/sign-of-effective-attachment/.

Signs of good attachment at the breast |

The baby’s chin indents the breast – no gap should be visible |

The baby’s mouth is wide open and has a wide angle |

The baby has a large amount of breast tissue in his/her mouth |

The baby’s bottom lip is curled outwards and top lip is neutral |

The baby’s cheeks are full and rounded – not sucked in |

More of the mother’s areola is visible above the baby’s top lip than at the bottom |

The way the mother holds her baby for breastfeeding is crucial, to ensure the baby feeds effectively. There is not one correct way to hold a baby for breastfeeding, but there are principles that should be in place that will enable the baby to feed comfortably and effectively (Table 2). These principles apply across the range of different positions for breastfeeding, such as laid back, side lying, across the mother’s body or under their arm.

2

Principles of positioning for breastfeeding. Adapted from https://www.unicef.org.uk/babyfriendly/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2020/04/Unicef-UK-Baby-Friendly-Initiative-education-refresher-sheet-3.pdf.

Acronym | Explanation of the principle |

C – Close | The baby’s body should be close to the mothers |

H – Head free | The baby’s head should be free to move back to enable him/her to open his/her mouth wide |

I – In line | The baby’s head and body should be in line with no twisting to ensure comfortable effective feeding |

N – Nose to nipple | The baby’s nose should start level with the mother’s nipple so that as (s) he reaches, a good mouthful of breast is taken and the nipple is at the roof of the mouth at the soft palate. |

S – Sustainable | The position should be sustainable and comfortable. The baby should be brought to the breast and the breast should not be lifted |

Hand expression of breastmilk

If mothers are shown how to hand express their breastmilk, this can enable them to resolve problems that might arise, such as engorgement, to enable them to continue to breastfeed. It is simple to demonstrate and only takes a few minutes, but has potential to enable women to breastfeed for longer.

It is important to encourage the mother to find a place where she feels relaxed and comfortable. To stimulate oxytocin and encourage the ‘let down’ of breastmilk, encourage the mother to relax and gently massage her breasts towards the nipple using a downward motion without dragging or pulling the breast tissue. Massage has been shown to increase the amount of breastmilk expressed.23 Once the mother is relaxed, explain that she should make a ‘c’ shape with her thumb and forefinger and grasp the breast around 2–3 cm behind the base of the nipple and squeeze and release in a rhythmic way until milk begins to flow (see USEFUL LINKS for a good video of hand expression of milk). This may not happen at once but soon a few drops will begin to appear. High quality review evidence suggests that if the baby cannot feed at the breast, it is important to express early after birth. Hand expression may be as effective as mechanical pumps and low cost pumps are as effective as larger more costly ones.23

PREVENTING AND MANAGING COMMON BREASTFEEDING CHALLENGES

Many women experience challenges when breastfeeding particularly in the early days. However, these can often be resolved through sensitive early support that includes identification of ineffective feeding and how positioning and attachment of the baby at the breast might be improved.

Sore and painful nipples

Nipple pain is common in the early weeks of breastfeeding and is one of the reasons women stop exclusive breastfeeding.24 It is distressing for mothers and can affect her relationship with her baby.25 Nipple pain can be caused by a range of factors such as poor positioning and attachment, ankyloglossia, (tongue-tie that restricts the movement of the tongue), infection and mastitis24,26. Most often pain can be resolved by improving position and attachment as when the baby is attached well and has a large mouthful of breast tissue, the nipple is against the soft palate at the back of the baby’s mouth and is therefore protected. It is important to watch the baby feeding to assess this carefully. Signs of poor attachment include a narrow gape, where the baby’s mouth is not open wide, pulled in cheeks and an equal amount of areola visible above and below the baby’s lips, the baby’s chin may not be touching the breast and when the baby finishes the feed the mother’s nipple is likely to be misshaped. It is also important to observe the baby’s suckling pattern as a baby feeding effectively will be suckling rhythmically and deeply with visible swallowing, rather than rapid shallow sucks without swallowing.

A Cochrane review of five possible interventions to treat nipple pain, including ointments such as lanolin, concluded that there was insufficient evidence to recommend these and that nothing or expressed breastmilk rubbed on the nipple was most likely to be effective in the short term.27 For most women who are supported to position their baby correctly, nipple pain will resolve within 10 days, but it is important to consider other possible causes such as skin conditions (e.g. eczema), Raynaud’s disease, abnormal sucking and tongue movement, engorgement or mastitis.

Engorgement, mastitis and breast abscess

Early recognition and effective management of engorgement is essential to prevent further problems such as non-infective mastitis, infective mastitis and breast abscess.28 It is important to distinguish between full and engorged breasts. Full breasts are firm and may have a marbled appearance but are easily softened when the baby feeds. However, when breasts are engorged this is painful and, because the breast tissue becomes edematous, milk does not flow easily and venous and lymphatic drainage may be impaired which may be exacerbated by flattened nipples. When a mothers’ breasts are full or engorged the feedback inhibitor of lactation (FIL), will reduce the future supply of breastmilk. It is therefore crucial to ensure removal of breast milk to both ensure ongoing supply and prevent blocked ducts and mastitis. Gentle hand expression should be encouraged to soften the breast tissue and enable the baby to latch effectively and feed. Frequent feeding should be encouraged and is the main course of action, as no treatments have been found to be effective to relieve engorgement.29

Mastitis can be identified by observing a tender, swollen and hot area of the breast that is often wedge shaped. The mother is likely to experience flu-like symptoms and have a raised temperature.28 This inflammatory response is caused by milk stasis, followed by components of the milk being forced through the cell walls into the capillaries or surrounding tissue. Frequent feeding from the affected breast prevents stasis and is therefore a key component in the management of mastitis. The baby feeding is the most effective way to drain the breast, however, as mastitis changes the taste of the breastmilk, making it saltier, which can discourage the baby from wanting to feed, hand expression may also be necessary. Anti-inflammatory drugs such as ibuprofen 400 mg three times as day can be helpful to reduce edema and to help the flow of milk. Pain relief such as paracetamol 1 g four times a day can be given to soothe discomfort. If the mother has less pain, this may help to reduce anxiety and encourage the release of oxytocin facilitating the ‘let down’ and flow of milk. Early support to continue frequent feeding and drainage of the breast is essential to prevent worsening of the inflammation or the development of a breast abscess.

Factors that can predispose to mastitis include anything that leads to poor or restricted drainage of the breast including poor attachment and ineffective feeding, limiting the frequency of feeds or amount of time breastfeeding, supplementary bottle feeds and use of pacifiers, the baby’s inability to suckle due to a short frenulum, pressure on or trauma to the breast, blocked ducts and maternal fatigue.29 There is no high quality evidence of any interventions to prevent mastitis.30

Mastitis is usually self-limiting and with early effective management and support often resolves quickly. However, if symptoms continue to worsen and no improvement is seen within 24 hours, infection may be present and antibiotics can be given, usually penicillinase-resistant penicillin, such as flucloxacillin 500 mg orally four times per day.28 There is a paucity of evidence on the effectiveness of antibiotic therapy for mastitis.31

Breast abscess can be a further complication of mastitis often caused by Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) and occurs in under 1% of women who breastfeed and around 3% of women who have had mastitis.32,33,34 A breast abscess is a localized collection of infected fluid that is characterized by a continuing hard and tender area of the breast35 (See USEFUL LINKS for links to photographs). Treatment is by either needle aspiration or surgical incision combined with antibiotic therapy. However, there is little high quality evidence to guide decisions about optimal treatment.36 Women should be encouraged to continue to breastfeed whilst being treated for a breast abscess but should ensure the baby’s face does not come into contact with any fluid draining from the breast.

Perceived low breast milk supply

It is common for women to believe they do not have sufficient breastmilk to feed their baby, often due to their baby being unsettled and feeding often. This is a global public health concern because it can lead to early cessation of breastfeeding and supplementation,37 which in turn puts babies at risk of higher morbidity and mortality. Actual breastmilk insufficiency is rare but can be due to factors such as inadequate glandular tissue from either hypoplastic breasts or following breast surgery or nipple piercing that can disrupt the ducts near the nipple and/or nerve pathways. It is important to recognise such situations and manage these appropriately. However, for most women low supply is perceived rather than real and can be resolved by frequent feeding in response to the baby’s needs – at least eight to ten times in 24 hours in the early weeks of feeding. Sensitive support for women is crucial to encourage frequent feeding and should include an explanation of how more feeding will increase prolactin levels and will result in higher milk production. It is also important to explain the need to avoid missed feeds, which can lead to full breasts and result in reduced breastmilk supply.

Conversations with women should also include ‘making the invisible visible’ by discussing ways of knowing the baby is getting enough milk.38 These signs include softer breasts following feeds, seeing milk around the baby’s mouth, increasing weight gain and the baby’s output. A baby should be passing yellow stools by the end of the first week of life and passing urine progressively more often each day during the first week, reaching at least six to eight times in 24 hours from day 7 onwards. Mothers should also be encouraged to be aware of the baby’s suckling pattern, which should include slow rhythmic suckles accompanied by swallowing. A clear demonstration can be viewed in a video link available in USEFUL LINKS.

Breastfeeding and neonatal jaundice

Physiological jaundice is caused by the breakdown of red blood cells as the newborn adapts to extrauterine life. Visible physiological jaundice occurs in over half of newborns and in most does not pose a threat to health. However, careful management is important because high levels of bilirubin can accumulate in the baby’s brain causing kernicterus which can result in damage to the brain. The prevalence of hyperbilirubinemia has improved in high income countries but there remains concern in LMICs where the prevalence is believed to be high.36 Normally in most healthy newborns levels of bilirubin peak between 96 and 120 hours after birth and resolve over the first week.38 Jaundice tends to make babies lethargic and they may not breastfeed well; however, it is important to ensure good nutrition, as this is needed for metabolism of bilirubin. Mothers should be encouraged to observe their baby for feeding cues and to feed as often as possible. Support should be offered to ensure the baby is feeding effectively. Skin to skin contact may also encourage breastfeeding. If the baby is not feeding well, it may be necessary to hand express breastmilk and offer this via syringe or spoon. This management should continue if the baby requires phototherapy. The recommendations for cut-off levels of serum hyperbilirubinemia for phototherapy and exchange transfusion are available in USEFUL LINKS.38

Hypoglycemia and breastfeeding

Blood glucose levels are generally low in healthy babies in the first hours after birth as they adapt to extrauterine life.39 This is usually transient, as they mobilize glycogen from body stores to produce glucose and ketones from fat.40 Breastmilk helps with this process, so early breastfeeding after birth is crucial. Other management to prevent hypoglycemia includes standard care for all babies, such as early skin to skin contact between mother and baby which will calm the baby, maintain temperature, regulate the baby’s heart rate and encourage early feeding.

It is important to recognise babies at higher risk of hypoglycemia, as if symptomatic and not managed this can lead to neurological injury. Babies at higher risk include preterm, large or small for gestational age, babies of diabetic mothers, cold stress, asphyxia, or respiratory distress. If mothers have been administered intravenous glucose during labor or been administered betablockers, their baby will also be at higher risk.40 These babies should be monitored closely for visible signs of hypoglycemia including irritability, apnea, cyanosis, altered level of consciousness and may require blood glucose monitoring in addition to early frequent breastfeeding and skin to skin contact. Extra expressed colostrum given by syringe or naso-gastric tube may also help. If symptomatic with a low blood sugar result, some babies may need intravenous fluids.41,42,43

COUNSELING TO ENABLE WOMEN TO BREASTFEED

Evidence from a systematic review shows that counseling for breastfeeding women to overcome difficulties and implement good practices in a way that is supportive of their decisions is effective in improving any and exclusive breastfeeding at 4 and 6 months.44 This has formed part of the World Health Organization (WHO) guideline that makes recommendations on the implementation of counselling for breastfeeding.45 The Global Breastfeeding Collective is calling on countries to: “Improve access to skilled breastfeeding counselling, as part of comprehensive breastfeeding policies and programmes in health facilities” (see USEFUL LINKS for links to the full discussion).

Many women may need to take medication whilst breastfeeding, whether for an acute illness such as mastitis or perineal infection or for chronic conditions such as diabetes or hypertension. The majority of drug companies err on the side of caution and recommend that their product is not used during lactation, but this may be a disclaimer for responsibility by the company. This may be confusing and frightening for both the mother and her healthcare provider. It is outside the scope of this chapter to discuss the effects of all medication use during breastfeeding; however, The National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) provide a link to a comprehensive database of drugs and their effects on breastfeeding (see USEFUL LINKS for the hyperlink to Drugs and Lactation, a public access, peer reviewed database).

TEN STEPS TO SUCCESSFUL BREASTFEEDING

Almost 30 years ago WHO and United Nations Children's Fund, formally United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF), launched the original ten steps to successful breastfeeding as part of the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI). This simple strategy supported new mothers in the initiation and continuation of breastfeeding and provided health workers with simple evidence-based strategies to appropriately support women and their families. The ten steps recognise that breastfeeding gives infants the best possible start in life, whilst acknowledging that breastfeeding requires support, encouragement and guidance in order to be successfully established.46, 47 The ten steps were revised in 2009 with the latest revision in 2019.47

Globally the ten steps have been initiated in more than 152 countries. Substantial evidence has shown that BFHI works. In 2016 a meta-analysis of studies evaluating the BFHI indicated that the implementation of the BFHI increased exclusive breastfeeding by 49% and the initiation of breastfeeding by 66%.48 The meta-analysis found that in 29 studies implementation of BFHI and its supportive elements increased breastfeeding in the first hour following birth. Fifty-one studies in the meta-analysis demonstrated an increase in exclusive breastfeeding in the first 5 months and 47 studies found that implementation of the BFHI increased any breastfeeding in the first 6 months.48 However, at present, only 10% of births occur in a BFHI facility, perhaps because of the challenges of meeting all ten steps.49 The new steps are designed to be simpler and more achievable and could be utilized to move towards achieving the Sustainable Development goals (SDGs) particularly SDG 2 (end hunger) and SDG 3 (ensure healthy lives and promote well- being for all).50,47

In 2019 WHO introduced the Global Breastfeeding Scorecard to record country efforts to promote, protect and support breastfeeding. Each country can identify their progress and rates of breastfeeding across time. For example, Uganda data show that 66% of babies are breastfed within the first hour of birth compared to a regional average of 50% and a world average of 45%; however, excusive breastfeeding at 6 months is 43%.51 This scorecard is useful when used in conjunction with the WHO/UNICEF drive to increase exclusive breastfeeding rates to 70% by 2030, to align with the progress of the SDGs. Originally the World Health Assembly (WHA) exclusive breastfeeding target was set at 50% by 2025. However, to coincide with the timeline of the SDGs, WHO extended the targets for maternal, infant and child nutrition to 2030. Based on further evidence of improving exclusive breastfeeding rates globally, it was agreed that a goal of 70% by 2030 could be achieved. Presently the global rate stands at 38%.49,47 The ten steps can be seen in Table 3.

3

The Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding (2019). Accessed at: https://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/infantfeeding/bfhi-implementation-2018.pdf.

1a. Comply fully with the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes and relevant World Health Assembly resolutions |

1b. Have a written infant feeding policy that is routinely communicated to staff and parents |

1c. Establish ongoing monitoring and data-management systems |

2. Ensure that staff have sufficient knowledge, competence and skills to support breastfeeding |

3. Discuss the importance and management of breastfeeding with pregnant women and their families |

4. Facilitate immediate and uninterrupted skin-to-skin contact and support mothers to initiate breastfeeding as soon as possible after birth |

5. Support mothers to initiate and maintain breastfeeding and manage common difficulties |

6. Do not provide breastfed newborns any food or fluids other than breast milk, unless medically indicated |

7. Enable mothers and their infants to remain together and to practise rooming-in 24 hours a day |

8. Support mothers to recognize and respond to their infants’ cues for feeding |

9. Counsel mothers on the use and risks of feeding bottles, teats and pacifiers |

10. Coordinate discharge so that parents and their infants have timely access to ongoing support and care |

THE POLITICS OF BREASTFEEDING

Suboptimal breastfeeding has been attributed to around 12% of deaths of children under 5 years old.51 Factors operating at multiple levels affect the initiation and continuation of breastfeeding.52 These determinants are contextual and include health care provider support,53 the attitude and support offered by the father,54,55 women’s plans for employment,56,57 as well as advice and practices that undermine maternal confidence.58,59 Used individually or in combination, health system interventions such as the utilization of the BFHI, and home and community interventions such as home visits, support from fathers and the use of social media have been found to increase the duration and exclusivity of breastfeeding in LMICs.60,61

Although breastfeeding is a woman’s choice, and her choice should be supported. It must be recognised that the baby formula milk industry is worth 50 billion dollars to the global economy and is growing year by year.62 This growth may be partly due to the influence of aggressive marketing to health professionals. In the Philippines, work by Save the Children showed that baby formula milk companies were offering doctors, midwives, and local health workers gifts. Such practice is in violation of the International Code of Marketing Breastmilk Substitutes and Philippine law. It is estimated that there are 16,000 deaths a year due to formula feeding in the Philippines, but scaling up breastfeeding to a near universal level could prevent 823,000 annual deaths in children younger than 5 years.63 This would be a positive move for all LMICs. The violations reported in the Philippines have been reported in many other LMICs including Mexico, South Africa, Kenya and Indonesia which have been attributed to aggressive marketing and lack of knowledge of health care professionals.

INFANT FEEDING DURING HUMANITARIAN EMERGENCIES

Humanitarian emergencies result from conflict, natural disasters or any event(s) that threaten the health and well-being, safety or security of large numbers of people. Women and infants are especially vulnerable in humanitarian emergencies due to overcrowding, lack of access to food, unsafe water, poor sanitation and overwhelmed health systems. High mortality rates for infants are due to diarrheal disease, pneumonia and undernutrition. In these circumstances, breastfeeding is more important than ever to provide safe, accessible nutrition and protection from life-threatening diseases and death.51 Breastfeeding helps mothers in emergencies by reducing the incidence of postpartum hemorrhage and increasing birth intervals.64

There are many challenges to breastfeeding in humanitarian emergencies. Women experience fear, stress and trauma, they may be separated from their social networks, and lack a comfortable, private space for breastfeeding. Women’s other responsibilities such as collecting water, fuel and food for her family may limit her time for breastfeeding. There are common misconceptions about breastfeeding held by women, communities, and those involved in relief efforts, for example, the belief that stress and illness will reduce a mother’s milk supply.65 Possibly the greatest challenge to breastfeeding in humanitarian emergencies is the uncontrolled distribution of breastmilk substitutes (BMS).

Breastmilk substitutes (BMS) increase the risks for infants significantly, for example in villages in Pondicherry, affected by the 2004 tsunami, the incidence of diarrhea was three times higher in children fed with free BMS compared to breastfed children.66 Even when the mother is HIV positive, or during infectious disease epidemics/pandemics, such as COVID-19, the dangers of not breastfeeding far outweigh the low risk of transmission via breastmilk.67 Therefore, BMS should only be provided when no other option is available. Unfortunately, BMS are commonly distributed with other aid due to lack of awareness or commercial interests. UNICEF and WHO (2018) recommend that skilled personnel with no conflicts of interest should assess the need for BMS.68,69

Protecting, promoting and supporting breastfeeding should be prioritized during humanitarian emergencies. This includes tight control of the distribution of BMS, enabling women and babies to stay together, providing safe spaces such as breastfeeding tents, and training healthcare practitioners and peer supporters to provide information, and emotional and practical support. Women who have stopped breastfeeding can be supported to re-lactate. Where a mother has died, is too ill or is unable to breastfeed her baby, wet nurses or donor human breastmilk are safer than BMS, although policies should be in place for the storage and distribution of expressed human breastmilk. Educating the wider humanitarian response community about the importance of breastfeeding and the dangers of BMS is critical.

SUMMARY

Hormonal changes in pregnancy prepare women’s bodies for breastfeeding. Breast milk constituents provide all the nutrients a baby needs to grow and develop for the first 6 months of life. Breastfeeding has been shown to protect against gastrointestinal infections and malnutrition with estimates indicating that globally up to 820,000 infant lives could be saved annually if breastfeeding reached universal levels. WHO therefore recommends babies to be exclusively breastfed for the first 6 months of life. For women, making the decision to breastfeed is a very personal matter that may be influenced by numerous factors. For women living in LMICs and those displaced by humanitarian emergencies breastfeeding has great potential to reduce rates of newborn morbidity and mortality. It is imperative that health care professionals caring for pregnant, laboring and postnatal women are able to share knowledge about the significant benefits of breastfeeding and provide the required support and assistance to enable women to breastfeed. The Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative has taken great strides in improving breastfeeding rates, but this has mainly been realized in high-income countries. Upscaling rates of exclusive breastfeeding in LMICs requires leaders and policy makers to identify interventions that will fit with their local context and needs.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- Align local policies with the WHO/United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) Global strategy for infant and young child feeding.

- Implement the ten Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) steps in your local health facility.

- Lobby local and national health ministers to prevent the aggressive marketing of baby milk formulas.

- In order for a baby to feed comfortably he/she should be positioned so that they are Close to the mother with their Head free and their head and body Inline. The Nose should start at the level of the mother’s nipple and the position should be Sustainable.

- Conditions associated with breastfeeding including sore nipples, engorgement and mastitis can be resolved by ensuring effective positioning and attachment.

- Breastfeeding immediately after birth has been shown to increase the duration of breastfeeding and protect against gastrointestinal infections and malnutrition globally.

- Ensure skin to skin contact is undertaken for all women at birth if there are no medical contraindications

- WHO recommends exclusive breastfeeding (that is no other fluid or food unless medically indicated) for the first 6 months of life.

- Download and display in all maternity units and health centers the WHO infographs and posters.

- Develop CPD programs for all health workers around BFHI and breastfeeding support.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) of this chapter declare that they have no interests that conflict with the contents of the chapter.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

USEFUL LINKS

Infographs and posters to download from WHO to promote BFHI

https://www.who.int/nutrition/bfhi/infographics/en/

Breastfeeding in the first hour

Cut-off levels of serum hyperbilirubinemia for phototherapy and exchange transfusion

https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/259269

UNICEF Baby Friendly – hand expression

WHO Recommendations on newborn health

https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/259269

Photographs of mastitis and breast abscesses

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3900741/#CR4

Attaching your baby at the breast

Positions for mothers

What to do about nipple pain

Is your baby getting enough milk?

WHO counseling guideline

https://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/guidelines/counselling-women-improve-bf-practices/en/

WHO collective on investment in breastfeeding

NCBI Drugs and Lactation (LactMed)

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501922/

REFERENCES

World Health Organization. Implementation guidance: protecting, promoting and supporting breastfeeding in facilities providing maternity and newborn services: the revised baby-friendly hospital initiative, 2018. Accessed at: https://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/infantfeeding/bfhi-implementation-2018.pdf. | |

Friedrich MJ. Early initiation of breastfeeding. JAMA 2018;320(11):1097–9. | |

Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJ, et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. The Lancet 2016;387(10017):475–90. | |

Horta BL, Loret de Mola C, Victora CG. Breastfeeding and intelligence: a systematic review and meta?analysis. Acta paediatrica 2015;104:14–9. | |

The World Bank (2018) Exclusive breastfeeding (% of children under 6 months). Accessed at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.STA.BFED.ZS. | |

Geddes DT. Inside the lactating breast: the latest anatomy research. Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health 2007;52(6):556–63. | |

Wambach K, Spencer B. Breastfeeding and human lactation. Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2019. | |

Ramsay DT, Kent JC, Hartmann RA, et al. Anatomy of the lactating human breast redefined with ultrasound imaging. Journal of Anatomy 2005;206(6):525–34. | |

Uvnas-Moberg K, Petersson M. Oxytocin, a mediator of anti-stress, well-being, social interaction, growth and healing. Z Psychosom Med Psychother 2005;51(1):57–80. | |

Lee S, Kelleher SL. Biological underpinnings of breastfeeding challenges: the role of genetics, diet, and environment on lactation physiology. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism 2016;311(2):E405–22. | |

Black RE, Victora CG, Walker SP, et al. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. The Lancet 2013;382(9890):427–51. | |

Horta BL, Loret De Mola C, Victora CG. Long-term consequences of breastfeeding on cholesterol, obesity, systolic blood pressure and type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatrica 2015;104:30–37. | |

Ip S, Chung M, Raman G, et al. A summary of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality's evidence report on breastfeeding in developed countries. Breastfeed Med 2009;4(1):S17–30. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2009.0050. PMID: 19827919. | |

McFadden A, Gavine A, Renfrew MJ, et al. Support for healthy breastfeeding mothers with healthy term babies. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2017(2). | |

UNICEF, WHO. The extension of the 2025 Maternal, Infant and Young Child nutrition targets to 2030, 2018. Accessed at: https://www.who.int/nutrition/global-target-2025/discussion-paper-extension-targets-2030.pdf?ua=1. | |

Suderman M, Borghol N, Pappas JJ, et al. Childhood abuse is associated with methylation of multiple loci in adult DNA. BMC Medical Genomics 2014;7(1):13. | |

van IJzendoorn MH, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Ebstein RP. Methylation matters in child development: Toward developmental behavioral epigenetics. Child Development Perspectives 2011;5(4):305–10. | |

Bergman N. Breastfeeding and perinatal neuroscience. Supporting sucking skills in breastfeeding infants. Burlington: Jones and Bartlett Learning, 2013. | |

World Health Organization, United Nations Children’s Fund & World Bank Group. Nurturing care for early childhood development: a framework for helping children survive and thrive to transformhealth and human potential. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2018. | |

Britto PR, Lye SJ, Proulx K, et al. Nurturing care: promoting early childhood development. The Lancet 2017;389(10064):91–102. | |

Moore ER, Bergman N, Anderson GC, et al. Early skin-to-skin contact for mothers and their healthy newborn infants. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016(11). | |

Widström AM, Brimdyr K, Svensson K, et al. Skin-to-skin contact the first hour after birth, underlying implications and clinical practice. Acta Paediatrica 2019;108(7):1192–204. | |

Becker GE, Smith HA, Cooney F. Methods of milk expression for lactating women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016(9). | |

Kent JC, Ashton E, Hardwick CM, et al. Nipple pain in breastfeeding mothers: incidence, causes and treatments. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2015;12(10):12247–63. | |

McClellan HL, Hepworth AR, Garbin CP, et al. Nipple pain during breastfeeding with or without visible trauma. Journal of Human Lactation 2012;28(4):511–21. | |

Puapornpong P, Paritakul P, Suksamarnwong M, et al. Nipple pain incidence, the predisposing factors, the recovery period after care management, and the exclusive breastfeeding outcome. Breastfeeding Medicine 2017;12(3):169–73. | |

Dennis CL, Jackson K, Watson J. Interventions for treating painful nipples among breastfeeding women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014(12). | |

Amir LH, Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine Protocol Committee. ABM clinical protocol# 4: Mastitis, revised March 2014. Breastfeeding Medicine. 2014;9(5):239–43. | |

Mangesi L, Zakarija-Grkovic I. Treatments for breast engorgement during lactation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016. | |

Crepinsek MA, Crowe L, Michener K, et al. Interventions for preventing mastitis after childbirth. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010(8). | |

Jahanfar S, Ng CJ, Teng CL. Antibiotics for mastitis in breastfeeding women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009(1). | |

Amir LH, Forster D, McLachlan H, et al. Incidence of breast abscess in lactating women: report from an Australian cohort. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 2004;111(12):1378–81. | |

Egbe TO, Njamen TN, Essome H, et al. The estimated incidence of lactational breast abscess and description of its management by percutaneous aspiration at the Douala General Hospital, Cameroon. International Breastfeeding Journal 2020;15:1–7. | |

Kvist LJ, Rydhstroem H. Factors related to breast abscess after delivery: a population-based study. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 2005;112(8):1070–4. | |

Kataria K, Srivastava A, Dhar A. Management of lactational mastitis and breast abscesses: review of current knowledge and practice. Indian Journal of Surgery 2013;75(6):430–5. | |

Irusen H, Rohwer AC, Steyn DW, et al. Treatments for breast abscesses in breastfeeding women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015(8). | |

Sultana A, Rahman KU, Manjula S. Clinical update and treatment of lactation insufficiency. Medical Journal of Islamic World Academy of Sciences 2013;109(555):1–0. | |

Marshall JL, Godfrey M, Renfrew MJ. Being a ‘good mother’: managing breastfeeding and merging identities. Social science & Medicine 2007;65(10):2147–59. | |

Greco C, Arnolda G, Boo NY, et al. Neonatal jaundice in low-and middle-income countries: lessons and future directions from the 2015 don ostrow trieste yellow retreat. Neonatology 2016;110(3):172–80. | |

Walker M. Breastfeeding management for the clinician: Using the evidence. Jones & Bartlett Publishers, 2013. | |

WHO recommendations on newborn health: guidelines approved by the WHO Guidelines Review Committee. World Health Organization (WHO/MCA/17.07). 2017. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO, Geneva. | |

Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Postnatal glucose homeostasis in late-preterm and term infants. Pediatrics 2011;127(3):575–9. | |

Wight N, Marinelli KA, Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine. ABM clinical protocol# 1: Guidelines for blood glucose monitoring and treatment of hypoglycemia in term and late-preterm neonates, Revised 2014. Breastfeeding Medicine 2014;9(4):173–9. | |

McFadden A, Siebelt L, Marshall JL, et al. Counselling interventions to enable women to initiate and continue breastfeeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International Breastfeeding Journal 2019;14(1):42. | |

World Health Organization. Guideline: counselling of women to improve breastfeeding practices. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2018. | |

World Health Organization, United Nations Children's Fund. The Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative: monitoring and reassessment: tools to sustain progress. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1991; (WHO/NHD/99.2). Accessed at: http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/65380). | |

WHO. Global Breastfeeding Scorecard, 2019. Accessed at: https://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/infantfeeding/global-bf-scorecard-2019/en/. | |

Meek JY, Noble L. Implementation of the ten steps to successful breastfeeding saves lives. JAMA Pediatrics 2016;170(10):925–6. | |

WHO/UNICEF. Global nutrition targets 2025: breastfeeding policy brief (WHO/NMH/NHD/14.7). Geneva: World Health Organization, 2014. Accessed at: https://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/globaltargets2025_policybrief_breastfeeding/en/. | |

United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals: 17 goals to transform our world, 2015. Accessed at: https://sdgs.un.org/goals. | |

Black RE, Victora CG, Walker SP, et al. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. The Lancet 2013;382(9890):427–51. | |

Rollins NC, Bhandari N, Hajeebhoy N, et al. Why invest, and what it will take to improve breastfeeding practices? The Lancet 2016;387(10017):491–504. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01044-2. | |

Labbok M, Taylor E. Achieving exclusive breastfeeding in the United States: findings and recommendations. Washington: United States Breastfeeding Committee, 2008. | |

Bar-Yam NB, Darby L. Fathers and breastfeeding: a review of the literature. Journal of Human Lactation 1997;13(1):45–50. | |

Gibson-Davis CM, Brooks-Gunn J. The association of couple’s relationship status and quality with breastfeeding initiation. Journal of Marriage and Family 2007;69(5):1107–17. | |

Mirkovic KR, Perrine CG, Scanlon KS, et al. In the United States, a mother’s plans for infant feeding are associated with her plans for employment. Journal of Human Lactation 2014;30(3):292–7. | |

Hawkins SS, Griffiths LJ, Dezateuz C, et al. The impact of maternal employment on breast-feeding duration in the UK Millennium Cohort Study. Public Health Nutrition 2007;10(9):891–6. | |

Avery A, Zimmermann K, Underwood PW, et al. Confident commitment is a key factor for sustained breastfeeding. Birth 2009;36(2):141–8. | |

Brown CRL, Dodds L, Legge A, et al. Factors influencing the reasons why mothers stop breastfeeding. Canadian Journal of Public Health 2014;105(3):e179–85. | |

Olufunlayo TF, Roberts AA, MacArthur C, et al. Improving exclusive breastfeeding in low and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Maternal and Child Nutrition 2019;15(3):e12788. | |

Sinha B, Chowdhury R, Upadhyay RP, et al. Integrated interventions delivered in health systems, home, and community have the highest impact on breastfeeding outcomes in low- and middle-income countries. Journal of Nutrition 2017;147(11):2179S–87S. | |

PR Newswire. Global baby food and infant formula market 2018–2023: market forecast to grow from bn in 2017, to bn during 2018–2023. Press release, 16 April 2018. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/global-baby-food-and-infant-formula-market-2018-2023-market-forecast-to-grow-from-50bn-in-2017-to-69bn-during-2018-2023-300630204.html. | |

Save the Children. Don’t push it, 2018. Accessed at: https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/node/13218/pdf/dont-push-it.pdf. | |

UNICEF and WHO Breastfeeding in emergency situations, 2018. Available at: https://www.unicef.org/nutrition/files/8_Advocacy_Brief_on_BF_in_Emergencies.pdf Accessed: 30/07/2020. | |

Gribble KD, McGrath M, MacLaine A, et al. Supporting breastfeeding in emergencies: protecting women's reproductive rights and maternal and infant health. Disasters 2011;35(4):720–38. | |

World Vision. Supporting breastfeeding in emergencies: the use of baby-friendly tents, 2012. Available at: https://www.wvi.org/nutrition/article/breastfeeding-emergencies Accessed: 30/07/2020. | |

Adhisivam B, Srinivasan S, Soudarssanane MB, et al. Feeding of infants and young children in tsunami affected villages in Pondicherry. Indian Pediatrics 2006;43(8):724. | |

WHO. WHO/UNICEF Discussion paper. The extension of the 2025 Maternal, Infant and Young Child nutrition targets to 2030, 2016. Accessed at https://www.who.int/nutrition/global-target-2025/discussion-paper extension-targets-2030.pdf?ua=1. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards programme CLICK HERE)