This chapter should be cited as follows:

Harwood R, Kenny S, Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.415523

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Obstetrics Module

Volume 15

The puerperium

Volume Editors:

Dr Kate Lightly, University of Liverpool, UK

Professor Andrew Weeks, University of Liverpool, UK

Chapter

Neonatal Male Circumcision

First published: February 2021

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

INTRODUCTION

Summary

- Male circumcision is common; approximately 1 in 3 males are circumcised worldwide.

- The foreskin, which is removed during circumcision, is a sleeve of penile skin which protects the glans (head) of the penis. It contains nerves which could be important for sensation during intercourse.

- Circumcision is most commonly performed for cultural and religious reasons. This is often done in the neonatal period under local anesthetic.

- A non-retractile foreskin (phimosis) is rarely pathological in young boys and can usually be eased with topical steroid if it is causing symptoms.

- Pathological phimosis due to balanitis xerotica obliterans (BXO) can be successfully treated with preputioplasty and triamcinolone injection in approximately two-thirds of males. This preserves the foreskin by widening the opening of the foreskin to allow retraction.

- Circumcision can reduce the complication rates of recurrent urinary tract infection and high grade vesicoureteric reflux. It also reduces transmission of sexually transmitted diseases, particularly HIV. The World Health Organization supports national circumcision programs in countries with high rates of HIV.

- Complications of circumcision include bleeding, infection, meatal stenosis and urethral injuries.

- Children with hypospadias, epispadias, megaprepuce, buried penis and penoscrotal webbing should not undergo circumcision and should be referred to a pediatric surgeon for assessment.

Male circumcision is globally one of the most commonly performed surgical procedures, with approximately 1 in 3 males being circumcised worldwide.1 Circumcision is defined as the “surgical removal of the foreskin of males”2 and it is primarily performed for cultural and religious reasons in the Middle East, West Africa, Southern Asia and the USA.1 Whilst the origin of circumcision remains unknown,3 it is widely practiced in Judaism, who ritually circumcise male infants in a ceremony ‘bris’ on the 8th day of life, and Islam, for whom there is no fixed age or method for it to be performed. In the USA there are very high rates of circumcision, with up to 91% of white males being circumcised for primarily cultural reasons.4

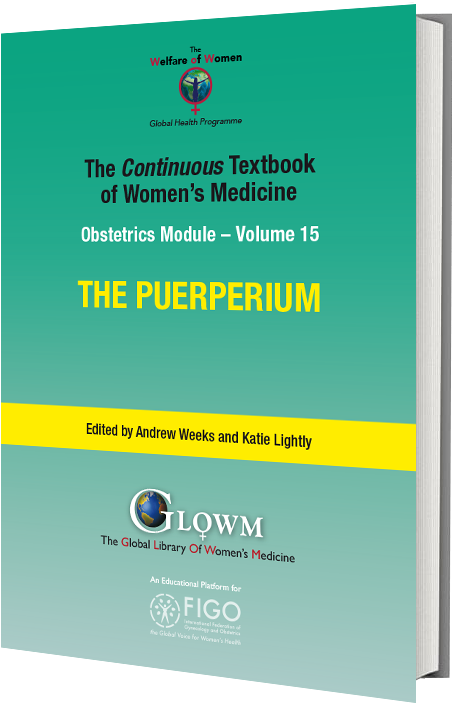

The foreskin, or ‘prepuce’ is a roll of skin which covers the glans penis (Figure 1). It develops between 3 and 4 months gestation5 and is thought to protect the glans, particularly when a child is in nappies, and contain nerves important for sensation during intercourse.6 In the neonatal period the foreskin is plastered to the glans of the penis, meaning that it almost universally cannot be retracted at this age. Over time the adhesions between the prepuce and the glans break down until the foreskin is retractile. The foreskin can balloon and become red and sore due to urine which collects behind a non-retractile foreskin (balanoposthitis) so as uncircumcised boys get older, encouragement of good hygiene and shaking/dabbing away the last drops of urine is essential. By the age of 12 years, 99% of boys can retract their foreskin enough to be able to see the external urethral meatus, and 60% of boys have full retraction of their prepuce.7 By 16–17 years only 1% of boys cannot fully retract their prepuce.8 Therefore, inability to retract the prepuce in a young boy is normal and does not constitute an indication for circumcision for medical reasons. Recurrent balanoposthitis is a relative indication, but in the vast majority of boys this is a self-limiting condition that does not mandate circumcision.

1

Normal penis. The foreskin envelops the glans penis circumferentially. The prepuce of neonates is plastered onto the glans (dashed lines) and this releases over time.

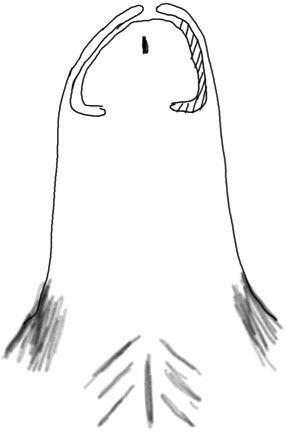

In children and older boys, the prepuce can occasionally cause problems. A skin condition called balanitis xerotica obliterans (BXO), which occurs in less than 1 in 1000 males,9 can affect the prepuce and the glans of the penis, causing a phimosis. Whilst this can respond to steroid creams it almost universally requires operative intervention.10 This is classically a circumcision, but preputioplasty and triamcinolone injection can also be therapeutic (Figure 2).11 BXO is extremely rare in boys under the age of 5 years.

2

(A) Circumcised penis. After circumcision the glans is exposed. (B) Penis after preputioplasty. The opening (meatus) of the foreskin is widened by three incisions. This allows the foreskin to be preserved and relieves the phimosis.

Taken together, there are very few medical indications for circumcision in boys under the age of 5 years and none in neonates. Non-retractile foreskins should be observed, and intervention only considered as boys approach puberty. In these situations, topical steroids can be successfully used to treat phimosis and avoid the need for circumcision.12

Paraphimosis occurs when the prepuce is retracted and not replaced over the glans. The inner prepuce and glans penis can become very edematous and it can become increasingly difficult to replace the foreskin. Generally, continuous circumferential pressure on the edematous area with a swab soaked in 50% dextrose enables the prepuce to be replaced. If replacement is not possible then a dorsal relieving incision can be performed under general anesthetic to widen the circumference of the prepuce and allow the prepuce to be replaced. A circumcision is rarely used in this situation as the edema can distort normal anatomy and it is unusual to have BXO as a cause of paraphimosis.

CONTRAINDICATIONS FOR CIRCUMCISION

All neonates should be given prophylaxis for vitamin K deficiency bleeding and, for an infant undergoing circumcision, this should be as an intramuscular injection. Circumcision is contraindicated in a jaundiced infant in whom any clotting disorder has not been screened for and corrected. Infants with a hematological disorder should not undergo circumcision and if there is a family history of significant bleeding, then this should be screened for prior to circumcision.

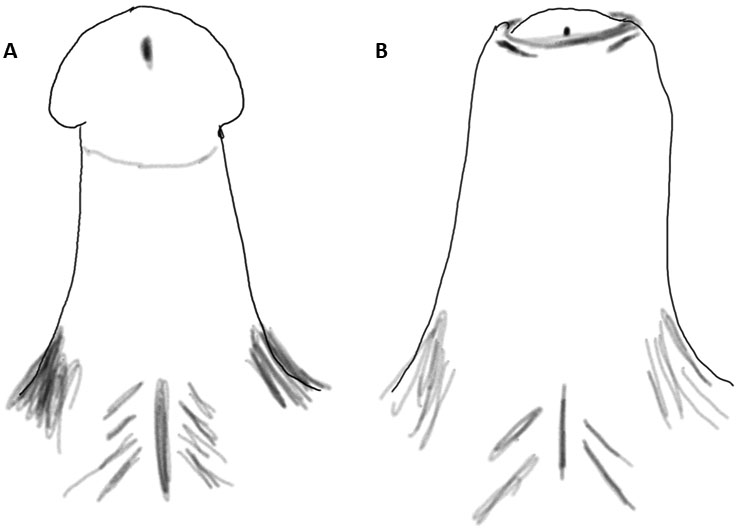

Hypospadias (Figure 3) is a widely prevalent congenital penile condition13 where the urethral meatus is not on the distal (the end) glans penis and can be located anywhere from the ventral aspect (underside) of the glans to the base of the penis. There is an associated ventrally deficient foreskin (absence of the foreskin on the underside of the penis) and sometimes a chordee (downwards bend of the penis). It is important not to perform a circumcision in this situation as the foreskin can be important for the reconstruction of the penis, particularly when the urethral meatus is more proximally placed as it can be used as a graft for the urethral plate. Other penile conditions including epispadias, megaprepuce, buried penis and penoscrotal webbing also require further assessment and the child should be referred to a pediatric surgeon. A relative contraindication to circumcision is a child with a large suprapubic fat pad. Circumcision in this situation can make the penis appear buried within the fat pad and also increase the risk of cicatrix formation and iatrogenic phimosis.

3

Hypospadias. Children with hypospadias have a foreskin which does not completely surround the glans penis and is deficient on the ventral aspect. The urethral meatus is positioned further down the penis. Sometimes there is a chordee (downwards bend in the penis). Circumcision is contraindicated as the foreskin can be used for reconstruction.

METHODS OF CIRCUMCISION

Circumcision of neonates and infants can be performed in a range of ways. The country, culture and religion all impact on the method of circumcision, the person who performs the procedure and the analgesia used. It is important that for whatever reason a circumcision is performed, the parents are fully informed about the benefits and risks of circumcision and any alternative options including preputioplasty and topical steroids discussed. Informed consent should be obtained by the person performing the circumcision and if this is not gained, then the circumcision should not be performed. In the UK, it is considered good practice to obtain consent for ritual circumcision from both parents.14

In Judaism the circumcision is performed by a Mohel, a trained non-medical Jew, without the use of local anesthetic. A blade is used to excise the outer prepuce, the inner prepuce is then peeled back and excised with scissors. A dressing is placed over the wound which is checked by the Mohel 24 hours later.

The majority of circumcisions of neonates and young infants are performed under local anesthetic. WHO, UNAIDS and JHPIEGO have published a Manual on male circumcision under local anesthesia15 which has detailed explanations of circumcision performed in this way. There are a number of devices that are used by non-surgeons to perform circumcision in clinics where there are large numbers of babies. All procedures are performed aseptically with analgesia of EMLA cream, a penile block and sucrose. The commonest in the UK is the Plastibell™ which is a single use plastic ring which is sized and placed under the foreskin after this has been retracted and the adhesions between prepuce and glans have been broken down. A dorsal slit can be required for accurate placement of the ring below the corona of the glans penis. The prepuce is then replaced and a ligature tightly tied around the prepuce and the groove of the ring, causing pressure necrosis of the skin. The distal foreskin is cut off, the baby discharged with regular analgesia and the Plastibell™ ring usually drops off after 5–8 days.

Two other devices are commonly used globally, the Mogen clamp and a Gomco clamp. Like the Plastibell™, these can also be used in clinics where there are high volumes of babies being circumcised.

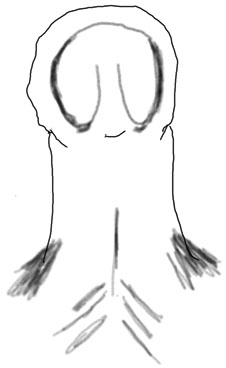

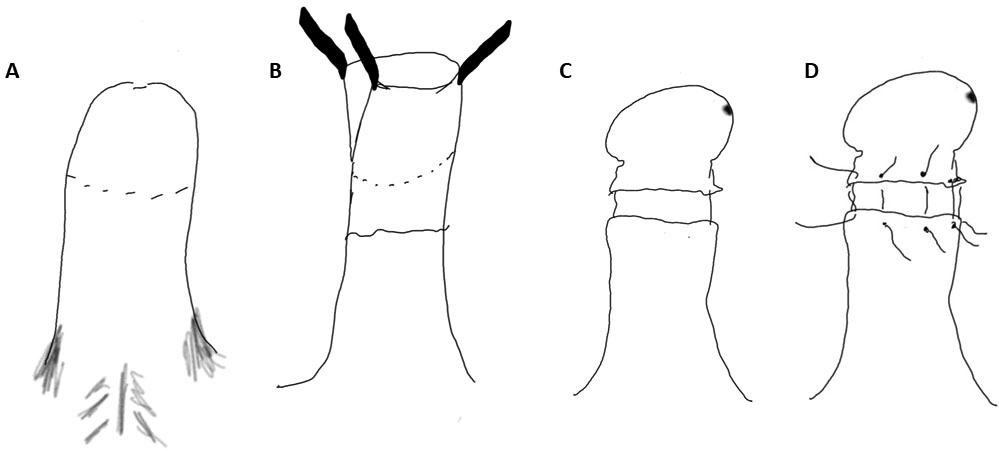

A surgical technique can be performed under local, or more commonly, general anesthetic (Figure 4). Surgeons use a variety of techniques to perform this, all of which involve incising the external and internal prepuce with a blade, scissors or bipolar diathermy, achieving hemostasis and suturing the incised edges together. Topical application of 1% chloramphenicol ointment twice daily for a week can stop the penis sticking to nappies or underwear. Routine application of petroleum jelly to the glans in the weeks following circumcision has been shown to reduce the risks of meatal stenosis.16

4

Steps of a surgical circumcision. (A) An incision of the external preputial skin is performed at the level of the corona (the rolled edge at the base of the glans penis). (B) The internal foreskin is elevated, a slit made on the dorsal aspect to allow the glans to be seen and the inner foreskin removed with 2–3 mm left under the corona. (C) In Jewish circumcision no sutures are placed and the edges are left to heal. (D) In surgical circumcision, hemostasis is achieved and sutures placed to bring the cut edges together.

COMPLICATIONS OF CIRCUMCISION

Complications of circumcision occur in up to 2% of cases and the rate of complication appears to be lowest for children <1 year age.17 Immediate complications of circumcision are rare but include excessive adhesions which require referral to a surgeon, excessive bleeding during surgery, glanular and urethral injury.15 Amputation of the glans has been reported, along with excessive skin removal, both of which require specialist surgical input.

The most frequent complication after circumcision is bleeding.18 This most commonly occurs at the frenular artery and will generally respond to continuous pressure which can be applied initially with two digits squeezing dorsally and ventrally. A circumferential dressing (which leaves the glans of the penis visible to ensure that the baby can pass urine and that the capillary refill of the glans remains good) can then be applied. Using a layer next to the penis which is hemostatic should be considered,19 but a careful eye needs to be kept on babies who bleed after circumcision as they can quite quickly develop significant anemia requiring transfusion and surgical reintervention for hemostasis. Infants with significant or persistent bleeding should be investigated for clotting disorders.

Infection is the second most frequent and important complication of which to be aware. Prevention using meticulous asepsis during the circumcision is important, followed by good wound care and postoperative chloramphenicol ointment application.20 However, severe infections can occur including necrotizing fasciitis21 and meningitis.22 Gram positive and Gram negative systemic antibiotic treatment should be used for infections in infants in nappies.

Later complications after circumcision include meatal stenosis which is reported to occur in up to 10% of boys who undergo neonatal and infantile circumcision.23 Urine flowmetry can confirm an obstructive pattern followed by urethral assessment under anesthetic. Urethral dilatation is sufficient for some, but others require meatotomy or meatoplasty.

Removal of insufficient skin can cause minor cosmetic dissatisfaction or scarring at the incision line resulting in an iatrogenic phimosis which requires a second circumcision.

There is mixed evidence on the impact of circumcision on sexual sensation and pleasure. Whilst histological data from the prepuce suggests that circumcision will not impact on sensation,24 there are strong patient reported data suggesting that circumcision, particularly performed during or after adolescence reduces glanular sensation and reduces orgasm intensity.25

The final, but possibly most important, concern about performing a circumcision in a neonate or infant is the lack of autonomy that the child has about the decision. When a circumcision is clinically indicated then there is a clear reason to proceed, but when it is performed for cultural or religious reasons the ethical balance of beneficence and non-maleficence is altered and this can have a life-long impact on that individual.26 This has led to proposals, since withdrawn, to ban circumcision for non-medical reasons in countries including Germany and Iceland.27

BENEFITS OF CIRCUMCISION

Over the past 30 years there has been an increasing body of literature about the benefits of circumcision. A systematic review has found that circumcision reduces the risk of urinary tract infection (UTI) in all boys; however, the number needed to treat (NNT) in normal boys is 111 to prevent one UTI. Given that the rate of complication after UTI is only 1–2%, there is no net clinical benefit. However, in boys with recurrent UTI, the NNT is 11 and those with high-grade reflux the NNT Is 4.28 The clinical benefit of circumcision in children at high risk of UTI is clear, but the current practice of waiting for a UTI to develop may mean that the opportunity to prevent renal scarring is missed.29 Offering circumcision during ablation of posterior urethral valves appears to be beneficial,30 but there is not yet a strong evidence base to support this practice for other antenatally diagnosed lower urinary tract anomalies.

PUBLIC AND GLOBAL HEALTH

Globally, the main impact of circumcision is the reduction of HIV infection in heterosexual men by 50–60%31,32 and reduction in human papillomavirus (which in turn reduces the risk of penile and cervical cancer), Chlamydia trachomatis, Trichomonas vaginalis and herpes simplex virus type 2.1,33 This has led to WHO supporting national circumcision programs in countries with high rates of HIV,34 in combination with promoting safer sex practices and provision of condoms, as barrier contraception is the best way to prevent infection. In countries where HIV has low prevalence the benefit of routine circumcision is unclear and, therefore, not currently routinely recommended. Whilst the incidence of penile cancer is reduced after circumcision, it has such a low incidence that 300,000 circumcisions need to be performed to prevent one case of penile cancer.35

Routine neonatal circumcision is debated amongst medical professionals. Some feel that the benefits of neonatal circumcision outweigh the risks;36 however, this approach disregards the autonomy of the male neonate undergoing circumcision and there are many reports of circumcision regret, although this is poorly described in medical literature.

CONCLUSIONS

Neonatal and infantile circumcision is performed for medical, religious and cultural reasons. Circumcision reduces the rate of urinary tract infections in boys and reduces the rate of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections. Once circumcised, other penile conditions such as balanitis and BXO are reduced. However, circumcision is not a procedure that can be performed without risks, some which can be life-threatening or life-changing. Deciding whether a circumcision should be performed requires a balance of all of these risks and benefits. Our recommendation is that if the procedure can be delayed until the child has the opportunity to be involved in the decision making process and express their autonomy, then every effort should be made to ensure that this happens.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- Circumcision should not be performed in boys with hypospadias, epispadias, buried penis, megaprepuce or penoscrotal webbing.

- Familial bleeding history should be elicited prior to circumcision and intramuscular vitamin K should be given prophylactically to all infants and neonates undergoing circumcision.

- Informed consent should be gained prior to performing circumcision, including the benefits and risks to the patient, including risks that are life-threatening and life-changing.

- Circumcision should be performed aseptically, by an appropriately trained individual using local or general anesthetic.

- Postoperative bleeding should initially be controlled with direct pressure. Careful monitoring for ongoing bleeding in neonates and young infants is important as they can rapidly become significantly anemic.

- Therapeutic circumcision in boys under the age of 5 years is rarely indicated and the use of alternatives such as topical steroids and preputioplasty should be offered.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) of this chapter declare that they have no interests that conflict with the contents of the chapter.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

REFERENCES

WHO. Neonatal and child male circumcision: a global review 2010. | |

Collins. Collins English Dictionary 2019. | |

Dunsmuir W, Gordon E. The History of Circumcision. BJU International 1999;83:1–12. | |

Morris B, Bailis S, Wiswell T. Circumcision Rates in the Unnited States: Rising or Falling? What Effect Might the New Affermative Pediatric Policy Statement Have? Mayo Clinic Proc 2014;89:677–86. | |

LA F, CM B, WS C, et al. Development of the human foreskin during the fetal period. Histol Histopathol 2012;27:1041–5. | |

Denniston GC, Hill G. Circumcision in adults: effect on sexual function. Urology 2004;64;1267; author reply 1268, doi:10.1016/j.urology.2004.03.059. | |

Agarwal A, Mohta A, Anand R. Preputial retraction in children. Journal of Indian Association of Pediatric Surgeons 2005;10:89–91. | |

Oster J. Further Fate of the Foreskin. Incidence of Preputial Ashesions, Phimosis and Smegma among Danish Schoolboys. Arch Dis Childh 1968;43:200. | |

Kizer WS, Prarie T, Morey AF. Balanitis xerotica obliterans: epidemiologic distribution in an equal access health care system. South Med J 2003;96:9–11. doi:10.1097/00007611-200301000-00004. | |

Hartley A, Ramanathan C, Siddiqui H. The surgical treatment of Balanitis Xerotica Obliterans. Indian J Plast Surg 2011;44:91–7. doi:10.4103/0970-0358.81455. | |

Wilkinson DJ. et al. Foreskin preputioplasty and intralesional triamcinolone: a valid alternative to circumcision for balanitis xerotica obliterans. J Pediatr Surg 2012;47:756–9. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2011.10.059. | |

Moreno G, Corbalan J, Penaloza B, et al. Topical corticosteroids for treating phimosis in boys. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014:CD008973. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008973.pub2. | |

Springer A, van den Heijkant M, Baumann S. Worldwide prevalence of hypospadias. J Pediatr Urol 2016;12:152 e151–7. doi:10.1016/j.jpurol.2015.12.002. | |

BMA. Non-therapeutic male circumcision and the law 2019. <https://www.bma.org.uk/advice/employment/ethics/children-and-young-people/non-therapeutic-male-circumcision-of-children-ethics-toolkit/4-non-therapeutic-male-circumcision-and-the-law>. | |

WHO, UNAIDS, JHPIEGO. Manual for Male Circumcision under Local Anaesthesia 2009. | |

Al-Abdi SY. Petroleum jelly for prevention of post-circumcision meatal stenosis. J Clin Neonatol 2013;2:113–4. doi:10.4103/2249-4847.119988. | |

El Bcheraoui C, et al. Rates of adverse events associated with male circumcision in U.S. medical settings, 2001 to 2010. JAMA Pediatr 2014;168:625–34. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.5414. | |

Wiswell T, Geschke D. Risks from circumcision during the first month of life compared with those for uncircumcised boys. Pediatrics 1989;83:1011–5. | |

Mano R, Nevo A, Sivan B, et al. Post-ritual Circumcision Bleeding-Characteristics and Treatment Outcome. Urology 2017;105:157–62. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2017.03.038. | |

Krill AJ, Palmer LS, Palmer JS. Complications of circumcision. ScientificWorldJournal 2011;11:2458–68. doi:10.1100/2011/373829. | |

Woodside JR. Necrotizing fasciitis after neonatal circumcision. Am J Dis Child 1980;134:301–2. doi:10.1001/archpedi.1980.02130150055015. | |

Scurlock JM, Pemberton PJ. Neonatal meningitis and circumcision. Med J Aust 1977;1:332–4. | |

Wang M-H. Surgical Management of Meatal Stenosis with Meatoplasty. Journal of Visualized Experiments 2010. doi:10.3791/2213. | |

Morris BJ, Krieger JN. Does male circumcision affect sexual function, sensitivity, or satisfaction?–a systematic review. J Sex Med 2013;10:2644–57. doi:10.1111/jsm.12293. | |

Bronselaer GA, et al. Male circumcision decreases penile sensitivity as measured in a large cohort. BJU Int 2013;111:820–7. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11761.x. | |

Lempert AD. Dutch on male circumcision. Non-therapeutic excision of the foreskin. BMJ 2010;340:c3437. doi:10.1136/bmj.c3437. | |

Sherwood H. The Observer 2018. | |

Singh-Grewal D, Macdessi J, Craig J. Circumcision for the prevention of urinary tract infection in boys: a systematic review of randomised trials and observational studies. Arch Dis Child 2005;90:853–8. doi:10.1136/adc.2004.049353. | |

Malone PS. Circumcision for preventing urinary tract infection in boys: European view. Arch Dis Child 2005;90:773–4. doi:10.1136/adc.2004.066779. | |

Wragg R, et al. The postnatal management of boys in a national cohort of bladder outlet obstruction. J Pediatr Surg 2019;54:313–7. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.10.087. | |

Gray RH, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in men in Rakai, Uganda: a randomised trial. The Lancet 2007;369:657–66. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(07)60313-4. | |

Auvert B, et al. Randomized, controlled intervention trial of male circumcision for reduction of HIV infection risk: the ANRS 1265 Trial. PLoS Med 2005;2:e298. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0020298. | |

Grund JM, et al. Association between male circumcision and women's biomedical health outcomes: a systematic review. The Lancet Global Health 2017;5:e1113–22. doi:10.1016/s2214-109x(17)30369-8. | |

WHO & JHPIEGO. 2018. | |

AAFP. Neonatal Circumcision, <https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/neonatal-circumcision.html> 2019. | |

Morris BJ, et al. Early infant male circumcision: Systematic review, risk-benefit analysis, and progress in policy. World J Clin Pediatr 2017;6:89–102. doi:10.5409/wjcp.v6.i1.89. |

FURTHER READING

Neonatal and child male circumcision, a global review. World Health Organization, 2010. | |

Male Circumcision Under Local Anaesthesia. World Health Organization, 2009. | |

Grund JM, et al. Association between male circumcision and women’s biomedical health outcomes: a systematic review. The Lancet Global Health 5:e1113–e1122. | |

Morris BJ, et al. Early infant male circumcision: Systematic review, risk-benefit analysis, and progress in policy. World J Clin Pediatr 6:89–102. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards programme CLICK HERE)