This chapter should be cited as follows:

Herter LD, Borges JBR, et al., Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.418483

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Gynecology Module

Volume 2

Adolescent gynecology

Volume Editor: Professor Judith Simms-Cendan, University of Miami, USA

Chapter

Breast Disorders in Pediatric and Adolescent Patients

First published: June 2023

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

INTRODUCTION

In pediatric and adolescent patients, the vast majority of patients with breast abnormalities are found to have benign and self-limiting conditions. Nevertheless, it is quite common for patients and their families to be anxious when presenting for evaluation of a breast lump or other concern. Because breast tissue is a site of hormonally induced changes especially at puberty, congenital and inflammatory disorders, as well as tumors, inspection and palpation of the breast is an obligatory component of physical examinations, even for newborns. Gynecologists who treat children and adolescents must be prepared for this type of examination and any subsequent diagnostic or therapeutic approaches, thoroughly addressing concerns yet avoiding unnecessary invasive procedures. This chapter reviews the evaluation and management of breast disorders observed in pediatric and adolescent populations.

EMBRYOLOGY

The breast originates from the ectoderm and mesenchyme. Its development begins in embryos during the fifth to sixth week as a longitudinal ectodermal thickening on the ventral portion of the embryo, forming milky lines.1 Approximately ten mammary buds are formed in each of these lines, extending from the armpit to the groin. However, by the tenth week, most buds atrophy, with only those in the lateral thorax remaining, whose ectodermal cells proliferate and penetrate deeper into the mesenchyme, forming 15 to 25 solid cords that will give rise to mammary glands and ducts.2 Later, other structures of ectodermal and mesodermal origin, such as conjunctive and adipose tissues, join these glands. Peripheral nerves, blood, and lymph vessels grow within the loose mesenchyme. By the end of the 30th week of intrauterine life, primitive ducts acquire lumen and are exteriorized through a papillary pouch. Between the 30th and 32nd week, this pouch regresses, forming the papilla and the areola. Finally, between the 32nd and 40th week, the lobular structures are differentiated and the nipple-areola complex (NAC) gains pigmentation.1 Later in childhood and puberty, under the influence of steroid hormones (estrogens and progesterone), the breast buds enlarge and glandular elements appear.3

ANATOMY

The breast is considered a modified and specialized type of an apocrine gland, covered by skin and subcutaneous tissue, situated in the anterior part of the thorax, overlying the pectoral muscles covering the second to the sixth rib. The medial border of the breast is the lateral margin of the sternum, and the lateral border is the anterior axillary line. Its upper and lower borders are the clavicle and the costal margin of the upper rectus abdominis sheath, respectively.4

The breast consists of glandular, adipose, and connective tissues. The glandular tissue is arranged in approximately 15 to 20 lobes, a ramified structure composed of 20–40 lobules that consist of 10 to 100 acini each. The acini are lined with a single layer of milk-secreting epithelial cells and are surrounded by contractile myoepithelial cells.5 The duct system consists of a main collecting duct that is formed by a variety of small intralobular ducts, which connect to the acini lumens. The main duct drains towards the nipple, where it dilates, forming the lactiferous sinus, which empties into the nipple orifices. The nipple is surrounded by a pigmented areola, which represents the central portion of the breast. The areola includes 10 to 15 tiny sebaceous glands around its perimeter, which are referred to as Morgagni tubercles, or, after pregnancy, Montgomery tubercles. The glandular tissue is embedded in fat, the lobules are separated by connective tissue septa (Cooper's ligament), which runs from the subcutaneous tissue to the chest wall.

BREAST EXAMINATION

Breast examination should be performed at all ages, including infancy in association with the annual physical examination visit, regardless of specific complaints. In newborns, breast tissue is usually evident due to stimulation from maternal hormones and may present with a white nipple discharge. In infants, problems that may be identified include accessory nipples, infection, hemangioma, lipoma, and lymphangioma.6 In prepubertal children, special attention should be paid to precocious development of the gland. Inspection and palpation of the breast, as well as description of the pubertal stage according to Tanner criteria3 are required. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Bright Futures guidelines, breasts should be evaluated for sexual maturity between 11 and 21 years of age.7 During examination, adolescents should initially be seated with their arms relaxed at their sides. Breast number, volume, symmetry, and contours should be observed. Skin inspection (color, scars, vessels, stains, hyperemia, edema, hair, ulcers, and wounds) is also important. Regarding the NAC, alterations in form, dimension, symmetry, color, and retractions may be observed. Thoracic and shoulder girdle deformities (kyphosis, scoliosis, costoesternal joint defects) may be identified. Subsequently, the patient’s arms should be extended and raised, and the skin and retractions in Cooper's ligaments should be observed.8

All breast tissue should be palpated in the supine position. The patient’s arms should be raised with her hands behind the nape of the neck, allowing better assessment of the axillary area and upper outer quadrants. Superficial and deep palpation should be performed smoothly over the entire length of the breast. The purpose of superficial palpation is to identify cutaneous and subcutaneous abnormalities, such as cellulitis and superficial nodules in the mammary gland. The digital pulp should cover the four quadrants with sliding movements. Deep palpation is performed in concentric circles with fingers flat, pressing towards the chest wall to identify deeper structures. All four quadrants (upper outer, lower outer, upper inner, and lower inner) should be palpated. Finally, the nipple should be gently squeezed, or if old enough, the patient can perform this for the examiner. If nipple discharge occurs and it is not galactorrhea, its characteristics must be recorded and the material collected for cytopathological analysis.

If axillary or supraclavicular lymph nodes are palpable, their size, characteristics (soft or hardened, mobile, or fixed) and quantity (single, multiple, or fused) should be described. Fused or matted lymph nodes may suggest breast or systemic cancer (such as lymphoma).4 The patient should also be checked for abnormal breast development, such as axillary accessory breasts. Clinical examination allows physicians to reassure their adolescent patients about the normal development of their breasts or, if not, to identify any abnormalities.

BREAST ABNORMALITIES

Abnormal breast development, which affects 2% to 6% of women,9 involves a variety of clinical forms. In some cases, it occurs when the embryonic milk line fails to regress and can include extra breasts (polymastia), nipples (polythelia) or areolas (polythelia areolaris). However, other abnormalities involve changes in gland tissue, such as asymmetries and agenesis. In some patients, these anomalies could be markers for other conditions, most notably urologic malformations and malignancies.10 These abnormalities may cause intense psychological suffering despite their benign course.

Amastia, Amazia and Poland Syndrome

Amastia, or breast agenesis, is a rare anomaly characterized by the total absence of breast tissue (glandular tissue and NAC) (Figure 1). Due to the absent NAC, the condition can be diagnosed in childhood. However, some patients are only diagnosed in puberty. Treatment consists of psychological support while waiting for the best time to perform breast implantation and construct the NAC.6 Amastia can also be associated with other anomalies, such as ectodermal dysplasia, Poland syndrome, and lipoatrophic diabetes, especially when it is bilateral.

1

Amastia in an adolescent with other genetic disorders (personal case, LDH).

Amazia differs from amastia in that the NAC is present but the glandular tissue is absent. Both are diagnosed by physical examination. Bilateral amazia should be differentiated from gonadal dysgenesis or sexual development disorders. In addition, bilateral amazia may be related to anomalies of the face, members, or vertebrae.13 Treatment is identical to amastia, except for the need to construct a NAC.

Poland syndrome is a rare congenital anomaly of unknown etiology, presenting variable clinical manifestations (Figure 2). It is characterized by partial or total absence of the major pectoralis, minor pectoralis, serratus, and amastia/amazia.11 Less commonly, rib and cartilage defects, subcutaneous tissue chest wall hypoplasia, ipsilateral brachysyndactyly, or alopecia of the axillary and mammary region may occur.12 Findings may be uni- or bilateral, but are more prevalent on the right side.

2

Child with Poland syndrome on the left side (personal case, LDH).

Although there is no known cause, the most accepted etiology is interruption of blood supply (due to hypoplasia of the subclavian artery or its branches) to the developing upper limb bud adjacent to the chest wall by the end of the sixth week of gestation.12 This can affect embryonic development of the thoracic musculature and the corresponding hand. It should be pointed out that there is no functional loss due to regional muscle compensation. Thus, it usually does not require surgical correction, except in cases of pulmonary herniation, breast hypoplasia, or major chest wall deformities.

Polymastia

Polymastia (Figure 3), supernumerary breasts, or accessory breasts, are synonyms of a clinical condition characterized by breast tissue in addition to the normal pair of breasts. Complete supernumerary breasts are rare; breast tissue without a NAC is more common. Although supernumerary breast tissue may be located along the entire length of the milk line, the most common site is the axillary region, followed by the thoracic region and, rarely, the vulvar region.14 Axillary breasts cause the most discomfort due to menses and lactation.15 Accessory breasts, especially without NAC, may be misdiagnosed as lipomas. Ultrasonography is sufficient to diagnose fibroglandular tissue. Surgical treatment includes total exeresis of the glandular tissue. Although it is recommended to postpone surgery until development is complete, in some cases, such as axillary breasts, exeresis is recommended at diagnosis due to the discomfort associated with the condition. During procedures in this region, special attention should be paid to the brachial plexus.

3

Polymastia on the left side (personal case, JBR).

Athelia and polythelia

Athelia is a very rare congenital condition in which the breast tissue is present, but there is no NAC. Diagnosis is clinical and the condition may be uni- or bilateral. Treatment consists of esthetic reconstruction of the NAC, preferably after the breast tissue has completely developed. On the other hand, polythelia is characterized by supernumerary NAC without the accompanying breast tissue. It is the most common congenital anomaly of the breast, resulting from the lack of milk line reabsorption during the embryonic period. The most common location is over normal breast tissue, near the NAC or the submammary fold (Figure 4). Diagnosis is clinical, but in some cases, it can be misdiagnosed as nevus. It requires ultrasound investigation for renal abnormalities.10 For esthetic purposes, surgery should only be performed after breast development is complete.

4

Areolar polythelia in the right breast (personal case, JBR).

Breast asymmetry

Breast asymmetry is a very common complaint during puberty and adolescence (Figure 5). The breasts may be asymmetric if one or both are abnormal, over-, or underdeveloped. Differences in breast size may be observed during puberty, but they usually attenuate after breast development is complete. Some degree of asymmetry is found in most women. However, when accentuated, it is a cause of concern for both the patient and her parents. Careful physical examination is needed to exclude breast nodules and abnormalities in the chest wall as factors. Ultrasound evaluation should be considered to evaluate for juvenile fibroadenoma, which can be difficult to palpate. The initial approach should include guidance about the stages of breast development and the probability of subsequent attenuation. Psychological support may be needed to alleviate anxiety and depressive symptoms. Surgical intervention should be postponed until breast development is complete, although the impact of psychological distress may be considered when determining the best time for surgical intervention. Esthetic surgery may include mammoplasty to reduce the larger breast or implants to augment the smaller breast. This decision should be based on patient preference.

5

Adolescent with breast asymmetry (personal case, LDH).

Tuberous breasts

Tuberous breast deformity is a relatively rare developmental variant characterized by typically underdeveloped, unusually shaped breasts (Figure 6). The etiology of this condition is unknown, but the most accepted theory involves the presence of a fibrous ring peripheral to the NAC that constricts expansion of breast parenchyma during the growth phase. This prevents lower breast growth, inducing a hernia near the NAC.16 Tuberous breasts are sometimes associated with induced puberty due to exogenous hormones, which suggests an endocrinological basis. Initial treatment encompasses psychological support and reassurance until the patient has reached emotional and skeletal maturity. During the physical examination, in addition to the shape of the breast, a NAC disproportionate to the breast body should be noted. Plastic surgery can improve breast size, shape, and contour. In some cases, more than one procedure is necessary.

A |

B |

6

(A) Adolescent with tuberous and asymmetric breasts. (B) Same patient after mastopexy (personal case, JBR).

HORMONAL CHANGES

Puberty induces breast development, called thelarche. During this process, estrogen causes the growth of adipose and ductal tissue, whereas progesterone stimulates lobular growth and alveolar budding.8 In normal puberty, thelarche occurs between 8 and 13 years of age.

Thelarche is usually bilateral but is sometimes ipsilateral initially. In such cases, the other side generally appears within 6 months. A firm, round, and homogeneous retroareolar nodule is usually produced, which is often accompanied by pain or tenderness. When unilateral, it must be distinguished from a true breast nodule.

Early thelarche

When thelarche begins prior to 8 years of age, it is considered precocious and should be evaluated. Except for neonatal thelarche, which does not require further assessment, other causes must be identified.

In cases where there is bilateral thelarche, progressive breast development, genital bleeding, darkened nipples, darkened or enlarged labia, leukorrhea, pubic/axillary hair, axillary odor, or increased growth velocity, assessment of serum luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), and estradiol levels, x-ray of the non-dominant hand and wrist to determine bone age, and pelvic ultrasound are warranted.

Neonatal thelarche

The breast bud becomes palpable at 34 weeks of gestation due to stimulation by maternal estrogen. Breast development usually regresses by the first month of life, after the fall of the placentally derived estrogen disappears.8 The reduction of the estrogen in early infancy leads to a transient increase in gonadotropins, which may induce some infant gonadal estrogen production allowing persistent presence of breast tissue for up to 2 years. The negative feedback mechanism of estrogen on the hypothalamus and pituitary usually becomes increasingly sensitive at around 6 to 24 months, reducing gonadotropin levels, which remain low until the onset of puberty. Under normal circumstances, the breast tissue remains dormant until puberty.17

Some breasts in infancy present as a nodule (Tanner stage 2), but others progress to Tanner stage 33 as illustrated in Figure 8. Concomitant galactorrhea may also occur, also called witch’s milk. During this neonatal period, due to residual placental estrogenic stimulus, the baby, may present other symptoms of estrogenic stimulation, such as mucorrhea and darkening and enlarging of the labia minora and majora, and may be noticed to have a small amount of vaginal bleeding when estrogen levels decline as gonadotropin levels fall.

7

Neonatal bilateral thelarche (photo courtesy of Dr Noadja França).

Premature thelarche

Premature thelarche is precocious breast development without other signs of puberty. Most cases of premature thelarche resolve spontaneously. It is caused by increased estrogen receptor sensitivity in the breast and/or a small transient increase in estrogen.

In isolated premature thelarche, hormone levels (luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, and estradiol) are in the prepubertal range, as are pelvic ultrasound findings. In addition, x-rays of the hands and wrists indicate that bone age is within the normal range. There is no increase in growth velocity and pubarche and menstrual bleeding do not occur. An examination of the vulva will also show no estrogen stimulation (no darkening and/or enlargement of the labia minora or leukorrhea).

Thelarche variant

Most cases of premature thelarche resolve spontaneously. However, some girls progress to signs of central precocious puberty. This is called thelarche variant, a slowly progressive form of precocious puberty. The condition involves heterogeneous gonadotropin secretion; pulsatile follicle-stimulating hormone secretion falls between premature thelarche and precocious puberty, while luteinizing hormone secretion induced by gonadotropin-releasing hormone is similar to that observed in normal puberty.18

Figure 8 illustrates a case of a 3-year-old girl with isolated thelarche who progressed in thelarche at age 8 years, and menarche at age 10 years.

A |

B |

8

(A) A 3-year-old child with Tanner stage 4 isolated thelarche on the right side and no other signs of puberty. (B) The same child at 9 years of age: contralateral breast development and menarche began at 8 and 10 years of age, respectively (personal case, LDH).

Thelarche due to central precocious puberty

Central precocious puberty is due to the reactivation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone pulses before 8 years of age (Figure 9). In addition to the breast bud, the following can be identified: darkening of the areola and/or labia minora; physiological leukorrhea; menstrual bleeding; acne, seborrhea, or oily skin; axillary odor; pubic, axillary or perianal hair; growth velocity >6 cm/year; growth percentile ≥1 standard deviation above target height.

9

Seven-year-old girl with true precocious puberty (personal case, LDH).

Thelarche due to peripheral precocious puberty

Peripheral precocious puberty is the result of increased sex steroid levels with no evidence of activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis.19 Some causes include autonomic follicular cysts, hypothyroidism, McCune-Albright syndrome (Figure 10), granulosa cell tumor, exogenous use of sex steroids. In these cases, estradiol is usually increased, while gonadotropins are suppressed.

A | |

B |

C |

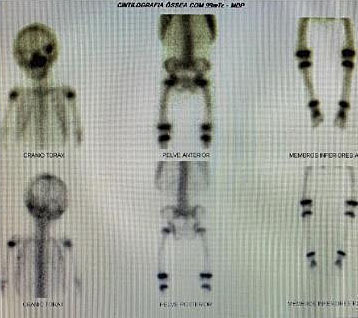

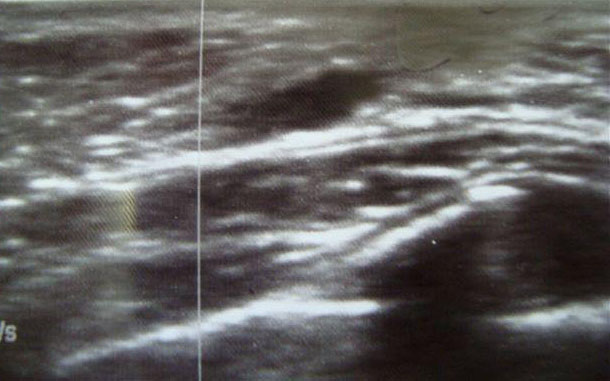

10

Two-year-old girl with McCune-Albright syndrome. Bilateral thelarche and genital bleeding. (A) Café au lait spots on the back of the neck. (B) Autonomic ovarian follicular cyst found in pelvic ultrasound. (C) Osteofibrous dysplasia found in bone scintigraphy (personal case, LDH).

Juvenile gigantomastia

Juvenile gigantomastia (also called macromastia or juvenile/virginal breast hypertrophy) is a rare breast development disorder20 characterized by rapid and excessive breast growth. It may affect one or, more commonly, both breasts despite normal estrogen levels.20 It occurs over an average period of 6 months, after which slower but constant growth continues. It can occur at any stage of puberty21 but often occurs before menarche.20 The breasts may be hot and erythematous due to rapid growth, simulating mastitis.

The etiology is unknown, but appears to be due to local hypersensitivity, either through changes in estrogen and progesterone receptors or the production of local growth factors.22 A familial pattern has been found in some cases23,24 and a relation to autoimmune diseases in others.25 Differential diagnosis should be made between juvenile gigantomastia and breast masses or obesity. Treatment consists of reduction mammaplasty or mastectomy, associated or not with drug therapy to block hormone action pre- or postoperatively.

Figure 11 illustrates an adolescent with juvenile gigantomastia who was treated with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog for 3 months to reduce estrogen stimulation and was followed up with 50 mg cyproterone acetate due to clinical unresponsiveness to tamoxifen. Twelve months after the condition had been stabilized, she underwent reduction mammaplasty and the esthetic response was excellent.

A |

B |

C |

11

(A) Juvenile gigantomastia patient 6 months after menarche. (B) Patient after 3 months of gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog therapy. (C) Patient 5 months after reduction mammaplasty and 50 mg cyproterone acetate therapy (personal case, LDH).

Lipomastia

In overweight or obese prepubescent children (body mass index ≥85th percentile for age and sex), breast enlargement may be caused by fatty tissue.26 Lipomastia is more apparent in the sitting than the supine position. Diagnosis is usually made clinically by placing the child in the supine position. During palpation under the areola, firm glandular tissue will not be detected. When the diagnosis is inconclusive, the child may be observed for 4 to 6 months for signs of pubertal progression. When necessary, ultrasonography will confirm a preponderance of fat.

Hypomastia

Hypomastia and breast hypoplasia are often difficult to separate from idiopathic small breasts. Bilateral breast hypoplasia is due to either low estrogen secretion or the breast tissue’s inability to respond to circulating estrogen.20

Inverted nipple

Occurring in 3% of patients, inverted nipples found in the pediatric adolescent patients are usually a benign variant of normal.27 In young patients they are usually congenital and bilateral. They may also be associated with genetic syndromes affecting the chest wall, or less often in this age group, acquired due to trauma, tumor, pregnancy, breastfeeding, surgery, or infection. During the physical examination, it is important to determine whether the nipple can be everted or if there is effusion, a palpable mass, or signs of inflammation. Evidence of discharge or mass should prompt further workup including imaging.

INFLAMMATORY, INFECTIOUS, OR PAINFUL CHANGES

The breast can be a site of infections, inflammation, or irritation, both in childhood and adolescence, but it is more common in the neonatal or pubertal period.

Friction against the nipples and areola from undergarments during to physical activity, especially in athletes, can cause pain or peeling of delicate skin. Suggestions for this problem include using silicon lubricant on the nipples, using cotton bras without stitching or seams on the front, and washing both the breast and bra with neutral soap.

Adolescents with large breasts are more likely to develop intertriginous mycotic infections in the inframammary fold. This is characterized by a red, itchy, shiny macular rash. These infections respond well to topical antifungals such as nystatin and ketoconazole. Patients should be instructed to keep the site dry and clean.

Eczema

Eczema of the areola (Figure 12) is more common in atopic patients and is usually bilateral. Treatment is the same for eczema elsewhere on the body, with barrier emollients and mid-potency topical corticosteroids as needed.

12

Eczema of the areola: dry, thickened, itchy, scaly skin (Personal case, JBR).

Mastitis and abscesses

Mastitis and abscesses are less common in adolescents than adults or infants.20 In children and adolescents, mastitis is most commonly caused by Staphylococcus aureus but may also be caused by Enterococcus, Streptococcus pyogenes (group A Streptococcus), anaerobic streptococci, Pseudomonas, Streptococcus agalactiae (group B Streptococcus), and Bacteroides spp. Other unusual organisms, such as Actinomyces, may be involved in patients whose infections are associated with nipple piercing (Figure 13). Risk factors include obesity, diabetes, immunosuppression, and glucocorticoid use. In some cases, the causal factor can be identified, which can include breast injury, ductal ectasia, epidermoid cyst, and suppurative hidradenitis or other local skin infection.20

13

Mastitis after nipple piercing (photo courtesy of Dr Roviana Rolim).

Clinical findings include areas of the breast with erythema, pain, warmth, edema all suggestive of cellulitis. Areas of fluctuation or purulent discharge from the nipple are indicative of abscesses,20 which may results in necrosis (Figure 14). Ultrasound may occasionally be necessary to identify the abscess. Bacteriological and Gram examination of purulent discharges can guide antibiotic therapy. If an abscess does not respond to antibiotic therapy, an incision and drainage or needle aspiration under ultrasound may be necessary.

Initial antimicrobial therapy is based on Gram staining if a pathogenic organism is identified. If Gram staining is unavailable, antibiotic coverage for S. aureus and group A Streptococcus should be provided. For immunocompetent children and adolescents with mastitis or a breast abscess who appear well and have no systemic symptoms, appropriate oral antibiotic agents include dicloxacillin, cloxacillin, cephalexin, clindamycin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (although the latter does not provide adequate coverage for group A Streptococcus). For children and adolescents with mastitis or a breast abscess who appear ill, have systemic symptoms, rapid progression of erythema, or are immunocompromised, appropriate parenteral antibiotic agents include cefazolin, nafcillin, or oxacillin if community-associated methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) is not a concern. However, clindamycin or vancomycin should be used if MRSA in endemic or suspected.28

14

Lactational abscess with necrosis in a 17-year-old puerperal adolescent (personal case, JBR).

Mastalgia

Breast pain is a very common complaint. It may be associated with thelarche, breast growth, pregnancy, ovulation, premenstrual period, hormonal contraceptives (especially in the first few months of use), exercise, fibrocystic disease, ovulatory period, breast cysts, stress, drug use, etc. Breast tenderness can be cyclic or acyclic. Cyclic tenderness is usually bilateral, occurs during the premenstrual period, and is often accompanied by breast engorgement.27 Physical examination should rule out other causes of pain, such as infection, tumors, cysts, and extramammary causes.

Treatment consists only of reassuring the patient and using bras with adequate support. When necessary, topical or oral analgesics or anti-inflammatories can be used. Oral contraceptives can help with cyclic breast pain by suppressing ovulation. In adults with severe breast pain that is refractory to conventional treatment, danazol or tamoxifen can be used. However, no safety studies of these medications have been conducted in adolescents. The literature lists treatments, such as reducing caffeine, evening primrose oil, and vitamin E, but these have yet to be scientifically proven.27

Mammary duct ectasia (blue breast)

Ductal ectasia consists of dilated subareolar ducts and periductal fibrosis and inflammation, with no clear etiological explanation. If the fluid within the subareolar cyst is dark, it can appear as a blue mass under the nipple, which is sometimes called “blue breast” (Figure 15). Ductal ectasia is the most common cause of bloody nipple discharge in infants (Figure 16). In general, the fluid collections resolve spontaneously within 9 months and do not require intervention. Occasionally infection occurs, and antibiotics may be necessary. Surgery is only needed for symptomatic and persistent masses.6

A |

B |

15

(A) Mammary duct ectasia (blue breast) apparent in the areola of an 8-month-old girl. (B) Echographic findings of ductal ectasia (personal case, LDH).

Nipple discharge

Nipple discharge or effusion, which is uncommon in children and adolescents, refers to liquid secretion from the nipple. When present, it may be hematic, colorless, milky, purulent, or greenish. It is important to identify whether the discharge is spontaneous or provoked and whether it is unilateral or bilateral.

The most common discharge is galactorrhea, i.e., unilateral or bilateral milk secretion. The most common causes are pregnancy, lactation, or endocrinopathies, although it can also be induced by medications such as antipsychotics. A sticky, colored discharge in this age group is most commonly due to ductal ectasia. Ductal ectasia is the most common cause of bloody nipple discharge in infants (Figure 16). Purulent discharge is often associated with a breast abscess. Less often, nipple discharge may be secondary to intraductal papilloma.

16

Three-month-old with hematic discharge from the nipple secondary to ductal ectasia (personal case, LDH).

In cases of galactorrhea, human chorionic gonadotropin, prolactin, and thyroid-stimulating hormone levels should be tested. For purulent secretions, Gram and culture assays can be performed to guide antibiotic therapy for infectious cases. For other secretions, a breast ultrasound can help in the differential diagnosis of other intramammary lesions.

NODULES AND CYSTS

Nodules are very infrequent in children and, in general, are related to the appearance of unilateral or bilateral thelarche. Although a breast lump in this age group rarely represents a malignant disease, it generates great anxiety in both the patient and family. It was found that of nearly 2 million breast cancer cases, only 0.02% occurred before age 21.29

Benign nodules tend to appear more frequently between 11 and 25 years of age and cysts after 24 years of age.30 Many nodules identified in the first imaging test for breast cancer have been present since early childhood but were not palpable.

Normal breast tissue can have nodularity that is difficult to distinguish from that of a true tumor. This difficulty occurs both for young women and their doctors. In a study of 542 patients under the age of 30 years, 80% of the masses were detected by the women themselves, only 53% were actually tumors, highlighting the difficulties of physical examination in young women.31

Ultrasonography is the imaging modality of choice in adolescents. Given the rarity of malignancy in this age group and the high breast density of young women, there is a higher rate of false-positive test results.30

When breast surgery is indicated in this age group, it should be pointed out that the scar will remain for life and that great care must be taken to differentiate the central subareolar breast bud and not confuse it with being a breast tumor. Care must be taken to spare this subareolar tissue because it is the origin of the ducts and the seat of the adipose tissue that forms the adult breast. Surgical damage to the breast bud has been reported to cause breast hypoplasia, significantly disfiguring young patients.30 Before excising any breast mass in prepubertal or pubertal patients, especially given that most masses are benign or self-limiting process, clear identification of the breast bud should be performed. Reckless injury to the breast bud through a surgery that is ill-suited for a benign process is unacceptable.32

The most common etiologies of breast masses in childhood and adolescence are benign and are detailed below.

Cysts

Breast cysts are common in adolescents and can be single or multiple. Their size and sensitivity may vary according to menstrual cycle phase. Many cysts regress within weeks or months. In symptomatic cases, analgesics or anti-inflammatories may be necessary. Cysts may arise from the mammary ducts (ectasia), Montgomery glands, or lymphangiomas on rare occasions.6

Palpation can identify homogeneous, round, rubbery nodules when no fever is present. Treatment includes simple guidance and follow-up, but if further evaluation is desired, ultrasound is the method of choice.

Ultrasound can be used to differentiate between cysts and solid masses.33 Cysts can be simple (anechoic content with thin, regular walls, caused by the dilatation of ducts that fill with fluid), complex (thick content – blood or pus) or, rarely in adolescents, atypical (irregular walls, with septa or vegetative growth, which might be associated with carcinoma).

Simple cysts will usually resolve spontaneously over a few weeks or months and do not require follow-up. However, when the sensitivity is intense and does not improve with behavioral measures, analgesics and anti-inflammatory drugs may be necessary. In larger and persistent symptomatic cysts, fine needle aspiration can be performed. If the fluid is bloody, cytological analysis is necessary.27

Fibrocystic disease

Fibrocystic changes, which are common in adolescents, are characterized by cysts, nodules, and thick cords that are more common in the upper outer quadrants.

The median age at diagnosis is 15 to 17 years. Given that physical examination findings tend to change each month, these young women can be followed clinically. Since these alterations are palpable in 50% of women and can be detected histologically in 90% of women, it is even questioned whether such findings indicate the presence of disease. These alterations, whose etiology is unknown, may occasionally be accompanied by serosanguineous nipple discharge. These changes are believed to result from an imbalance between estrogen and progesterone, and there is usually spontaneous improvement with menstruation, but analgesic and anti-inflammatory medications may be required for symptom relief. Ultrasonography may be necessary for differential diagnosis in unclear cases.34 If the pain is refractory or leads to psychosocial damage for the patient, oral contraceptives may improve symptoms in 70 to 90% of these young women.35

Fibroadenoma

Fibroadenomas are the most common breast lesion in adolescents,35 corresponding to 30 to 50% of breast masses in case series.36 Histologically, they consist of proliferating stroma that has been excessively stimulated by estrogen or has highly sensitive hormone receptors. In general, they are asymptomatic or have mild clinical symptoms, causing discomfort only in the premenstrual period. On examination, they are solid, mobile, well-circumscribed lesions with a fibroelastic consistency.37 Their average size is 2 to 3 cm and they are more commonly found in the upper outer quadrants of the breasts, perhaps due to the higher concentration of glandular tissue in this region.37 A fibroadenoma can be single, but up to 60% are multiple, being bilateral in up to 25% of the cases.38 Multiple or recurrent fibroadenomas are described in 10–25% of cases.39 The diagnosis is usually clinical, but ultrasound can be used in unclear cases. Fibroadenomas are characterized by an avascular, solid, well-circumscribed mass. Obtaining histological or cytological material through percutaneous biopsy should only be performed if phyllodes tumors or cancer are suspected. Mammography should not be performed in this age group. Most common fibroadenomas shrink or disappear completely over time.34 In general, accompanying the patient and reassuring her and her family is sufficient follow-up. However, in some cases of lesion growth, tumor size >5 cm, or the patient’s expressed desire for surgery, excision may be indicated. The patient and family must be informed about the inherent risk of surgery, scarring, breast asymmetry, decreased sensitivity, damage to the duct system, etc. Association with malignant neoplasms is very rare (less than 0.5%), although it is more frequent in complex fibroadenomas (i.e., involving concurrent cysts, sclerosing adenosis, calcifications, and apocrine metaplasia), which are rare in this age group. Reports of malignancy associated with a preexisting fibroadenoma in adolescents are also rare.40

Juvenile fibroadenoma

Juvenile fibroadenomas are fast growing, reach sizes >5 cm, and can even replace normal breast tissue (Figure 17). They represent 7% to 8% of all fibroadenoma subtypes, and often occur in adolescents of African descent. They differ from common fibroadenomas in that they are larger and have a softer consistency, with a more cellular stroma. Skin ulceration or distended and prominent superficial veins may appear.41 When >5 cm, juvenile fibroadenoma is also called giant fibroadenoma. These nodules must be excised due to the difficulty of distinguishing them from phyllodes tumors.34

17

Juvenile fibroadenoma (personal case, LDH).

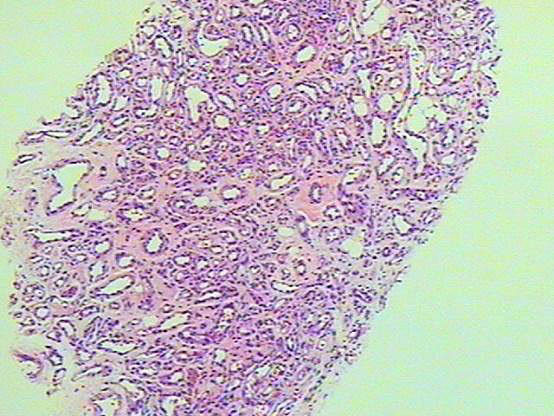

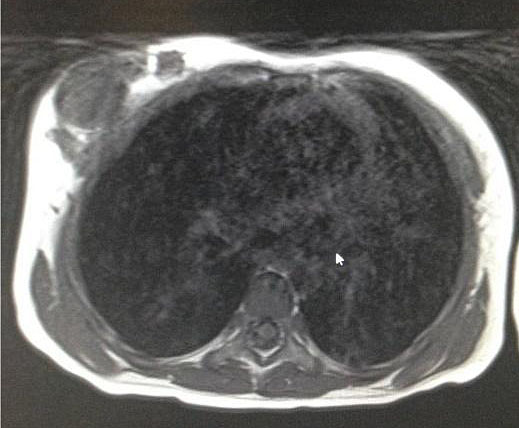

Phyllodes tumors

Phyllodes tumors, also known as cystosarcoma phyllodes, are rare primary tumors that are generally thought to occur in older women but, according to some authors, approximately 10% occur in women between 16 and 20 years old. They have been reported in girls as young as 10 years of age.40,42 Histologically, phyllodes tumors have a foliaceous morphology, from which their name is derived, and can generate nodules with quite varied biological behavior. These tumors are classified as benign, malignant, or borderline, depending on cell atypia, the number of mitoses, and observed infiltration of the margins. Epidemiologically, most phyllodes tumors are benign, particularly in adolescents. However, despite representing only 1% of malignant breast tumors in adults, in adolescents they are the most frequent malignant lesions.43 They are usually single, solid, painless masses and measure between 4 and 5 cm (but can vary between 1 and 20 cm). They can remain stable for a long period and then abruptly begin rapid growth. Sonographic findings may be suggestive (lobulated masses, heterogeneous pattern, and no microcalcifications), but the diagnosis can only be confirmed through histological evaluation. MRI can help distinguish between phyllodes tumors and fibroadenomas.44 The standard treatment is excision, but in borderline and malignant cases, more radical measures should be taken. Excision can be performed with 1 cm margins due to the risk of recurrence, even in tumors classified as benign,38 although the need for this margin is controversial.

Hamartomas

Breast hamartomas are uncommon lesions that consist of disorganized growth of mature breast tissue elements. Also known as fibroadenolipoma, chondrolipoma, or fibroblastic lipoma, they are benign lesions, commonly known as “breast-in-breast”, because they are a mixture of breast tissue and normal cells from surrounding areas. They comprise 0.7 to 4.8% of benign breast tumors. Since the term was first introduced in 1971, more than 300 cases have been reported, in which only four patients were under the age of 18 years (13, 14, 15, and 16 years).45,46 Thus, they are uncommon in adolescents and are usually not palpable, being asymptomatic in almost all cases. Hamartomas present as a painless, mobile, and well-circumscribed mass when palpable. Most patients have a single lesion. No fluctuations in lesion size due to the menstrual cycle have been described.

In pediatric and juvenile populations, ultrasound should be the initial test. Typical sonographic features include a well-circumscribed mass of heterogeneous density ranging from echo-lucent to echogenic.47

Institutional experience of more than 17 years with breast hamartomas in seven adolescent patients showed that, despite being benign, these lesions can grow rapidly and reach a large size, and recurrence can occur if excision is incomplete. They can be diagnosed by core needle biopsy with adequate clinical and ultrasound correlation.48

Treatment is conservative, and biopsy should only be performed in doubtful cases. Surgical excision should be considered for large or rapidly growing masses.

Juvenile papillomatosis

Juvenile papillomatosis (also known as “Swiss cheese disease”) is a benign proliferative disease of the breast’s ductal epithelium, more commonly observed in young women. The mean age of detection is 23 years (ranging from 12 to 48 years). In 28% of the cases, the patient has a relative with breast cancer, and 7% have a first degree relative with breast cancer.49 Its size can vary between 1 and 8 cm, but in general it is <3 cm.50 According to the literature, juvenile papillomatosis is a marker of familial breast cancer,50 involving a 10 to 15% risk of concomitant or future breast cancer, especially when there is a positive family history of breast cancer, when there are multiple or recurrent lesions, or lesions with atypical histological features.51 Ultrasound is the imaging test of choice, and the mass usually appears ill-defined and inhomogeneous, with numerous anechoic areas, mainly in the periphery.51 The treatment of choice is complete tumor excision with tumor-free margins, and the patient should be regularly monitored due to the increased future risk of cancer.

Hemangiomas and lymphangiomas

Enlarged breasts in prepubertal children can also be caused by hemangiomas (Figure 18) or lymphangiomas (Figure 19). Diagnosis may be suggested clinically but is confirmed with ultrasound. When necessary, magnetic resonance imaging has also been shown to be effective.34 If there is doubt about the diagnosis, fine-needle aspiration may be necessary. Lymphangiomas can become infected and present as soft masses.

|

|

18

Capillary hemangioma simulating unilateral thelarche (personal case, LDH).

|

|

19

Breast lymphangioma in a 2-year-old (personal case, LDH).

Intraductal papilloma

Intraductal papilloma is a tumor of the epithelial cells lining the terminal breast ducts, which project into the duct lumen; it is extremely rare in adolescents.38 The clinical manifestation is usually a subareolar mass, and it can be associated with bloody or serosanguineous nipple discharge. Ultrasonography may suggest the diagnosis.

Breast cancer

Given the low incidence of breast cancer in children, only large database assessments can provide an adequate sample size.52,53,54 Breast carcinoma before full breast development is extremely rare, only 0.0001% occur in girls younger than 19 years old.55

According to U.S. National Cancer Institute data, no cases of ductal carcinoma in situ occurred in women younger than 14 years between 2013 and 2017, and the incidence of invasive cancer was 0.2 per 100,000 women between 15 and 19 years old.56 Among such cases, juvenile secretory carcinoma (juvenile breast carcinoma) was the most common type (80%), followed by ductal carcinoma. The clinical picture is that of an irregular mass with a hard consistency, which may or may not be attached to deeper tissue. Other possible additional findings are skin or nipple retraction, orange peel skin, nipple discharge, and axillary lymphadenopathy.

Secondary breast cancer occurs more commonly in adolescents exposed to radiotherapy in childhood for lymphomas, mediastinal masses, or chest tumors. These children are at high risk of developing breast cancer and should be closely monitored by pediatric oncologists. Guidelines for childhood cancer survivors generally recommend that women who received chest radiation while being treated for childhood cancer begin breast cancer surveillance with mammography or MRI 8 years after treatment or at age 25, whichever occurs first.57,58

Most malignant breast masses are metastatic from other cancers, such as Hodgkin's lymphoma, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, neuroblastomas, hepatocellular carcinoma, and rhabdomyosarcoma.59 Rhabdomyosarcoma is one of the most common primary cancers that metastasize to the breast, occurring in 6% of breast cancer cases.41

Between 5% and 10% of breast cancers are due to inherited predisposition, especially mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, which are tumor suppression genes. The cumulative risk of breast cancer in women with these mutations ranges from 3.2% at age 30 to 85% at age 70.60 Another genetic syndrome associated with breast cancer risk is Li-Fraumeni, a germline mutation in the p53 tumor suppressor gene.61

Deciding about genetic screening in adolescents is a complex issue. On the one hand, new technologies can detect cancer more quickly, but on the other, finding out that they are at high risk can cause anxiety or other psychological complications in healthy young people.62 In such cases, qualified genetic counseling is critically important. Genetic testing for BRCA can be useful when the recommendations could have an impact, i.e., when MRI and other screening techniques can be offered to the patient. Current recommendations for women at genetic risk of breast cancer are consensus-based rather than evidence-based and include self-examination beginning at age 18, clinical breast examination beginning at age 25, and mammography or MRI beginning at age 25.63

MANAGEMENT OF BREAST MASSES

The challenge of breast tumors in adolescents is very different from that of adults, among whom core-needle biopsy is common, leading to tissue diagnosis prior to definitive treatment. However, needle biopsies are usually deferred in adolescents, with excision of masses preferred.

When a mass is found, the entire breast, axillary area, and supraclavicular fossa must be palpated on both sides. In addition, each palpable mass must be evaluated regarding size, location, mobility, inflammatory properties, texture, and adenopathy. Hardened, rapidly growing nodules connected to adjacent tissue planes or fused or hard axillary lymph nodes suggest malignancy at any age and should be properly investigated.

As mentioned earlier, for adolescents, ultrasonography, not mammography, is the examination of choice. It is important to reiterate that breast tumors have a low probability of malignancy in young people.

In adolescence there is greater social anxiety and misinformation regarding lumps, there is no established screening program for young people, and adolescents do not always have regular medical check-ups.

When assessing adolescents with a palpable breast tumor, three objectives must be met:

- Determine whether it appears to be benign,

- Maintain follow-up if managing conservatively, and,

- Determine whether surgical excision is needed.

When a small nodule with benign characteristics is detected for the first time on palpation in an adolescent, it can be observed for a few menstrual cycles to determine whether there is any change over time. A cyst, for example, may disappear or shrink. If it persists, a breast ultrasound may be required.

Asymptomatic or symptomatic masses considered small (<4–5 cm) and having the appearance of fibroadenoma in clinical examination and ultrasonography can be managed conservatively, and the young patient should be reassured. However, for large tumors that deform the breast, cause esthetic discomfort, or are painful, excision is recommended.

Some patients may desire surgical excision of smaller masses due to anxiety about the mass itself. For adolescents undergoing excision of a breast mass, more discreet incision sites are preferred, such as periareolar or inframammary locations. In cases where the doctor, the patient, or her family has some reservations about surgery, and the mass is concerning for increased malignant potential or occurring in a high-risk individual (e.g. a patient with a history of chest radiation therapy) core-needle biopsy should be performed because it is well tolerated, can further characterize the mass, and avoids surgical scars.64

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- The breast area begins changing even in the neonatal period and should be examined in annual evaluations at any age.

- More than 99% of lesions are benign in this age group.

- Polythelia (supernumerary NAC without breast tissue) is the most common congenital anomaly of the breast, requiring ultrasound investigation for renal abnormalities.

- Thelarche should only occur from the age of 8 years onwards. Before that, it is considered early and should be evaluated.

- Unilateral thelarche must be distinguished from a true nodule.

- Before excision, a nodule must always be differentiated from a breast bud (thelarche), since its inadvertent removal would cause amazia.

- Ductal ectasia is the most common cause of bloody nipple discharge in infants.

- In cases of milky discharge (galactorrhea), human chorionic gonadotropin, prolactin and thyroid-stimulating hormone assays should be requested.

- Fibrocystic changes are common in adolescents. They are characterized by cysts, masses, and thick cords that are more common in the upper outer quadrants.

- The most common breast complaint is mastalgia, which can be due to breast growth, hormonal stimulation during the premenstrual period, or to initiating hormonal contraceptives.

- Breast cysts are common in adolescents, can be single or multiple, and can cause pain. Some cysts disappear within a few weeks.

- Mastitis and abscess are more common in the lactation period.

- For immunocompetent children and adolescents with mastitis or breast abscess who appear well and have no systemic symptoms, appropriate oral antibiotic agents include dicloxacillin, cloxacillin, cephalexin, clindamycin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (although the latter does not provide adequate coverage for group A Streptococcus).

- The most valuable complementary examination in this age group is breast ultrasound.

- Due to high breast density, which makes it difficult to identify masses, and the low risk of breast cancer, mammography is not indicated in adolescents, and should be avoided to reduce exposure to ionizing radiation.

- The most common breast tumor in adolescents is fibroadenoma.

- Ultrasonography is always indicated for atypical, large (>5 cm), suspicious-looking, or rapidly growing mass. In certain cases, needle biopsy can clarify the diagnosis.

- Juvenile papillomatosis is a marker of familial breast cancer and should be excised.

- Juvenile secretory carcinoma is the most common type of primary breast cancer in adolescents, followed by ductal carcinoma. Rhabdomyosarcoma is one of the most common primary cancers that metastasize to the breast.

- Fused axillary or supraclavicular lymph nodes may suggest breast or systemic cancer (such as lymphoma).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) of this chapter declare that they have no interests that conflict with the contents of the chapter.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

REFERENCES

Forsyth IA. The mammary gland. Baillieres Clin Endocrinol Metab 1991;5(4):809–32. | |

Javed A, Lteif A. Development of the human breast. Semin Plast Surg 2013;27(1):5–12. | |

Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Arch Dis Child 1969;44(235):291–303. | |

Henderson JA, Duffee D, et al. Breast Examination Techniques. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls, 2022. | |

Medina D. The mammary gland: a unique organ for the study of development and tumorigenesis. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia 1996;1(1):5–19. | |

DiVasta AD, Weldom CB, Labow BI. The breast: examination and lesions. In: Emans SJ, Laufer MR, DiVasta AD (eds.) Emans, Laufer, Goldstein's Pediatric and. | |

American Academy of Pediatrics. Adolescence visits. In: Hagan JF, Shaw JS, Duncan PM (eds.) Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children and Adolescents, 4th edn. Elk Grove Village, IL: 2017. | |

De Silva NK. Breast development and disorders in the adolescent female. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2018;48:40–50. | |

Fama F, Cicciu M, et al. Prevalence of Ectopic Breast Tissue and Tumor: A 20-Year Single Center Experience. Clin Breast Cancer 2016;16(4):e107–12. | |

Kokavec R, Macuch J, et al. Polythelia is not a mere aesthetic issue. Acta Chir Plast 2002;44(1):3–6. | |

Jeung MY, Gangi A, et al. Imaging of chest wall disorders. Radiographics 1999;19(3):617–37. | |

Mentzel HJ, Seidel J, et al. Radiological aspects of the Poland syndrome and implications for treatment: a case study and review. Eur J Pediatr 2002;161(8):455–9. | |

Ozsoy Z, Gozu A, et al. Amazia with midface anomaly: case report. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2007;31(4):392–4. | |

Deb P, Swarup D, et al. Fibroadenoma of Aberrant Breast Tissue in the Vulva. Med J Armed Forces India 2000;56(2):153–4. | |

Evans GR, Ryan JJ. Reduction mammaplasty for the teenage patient: a critical analysis. Aesthetic Plast Surg 1994;18(3):291–7. | |

Mandrekas AD, Zambacos GJ, et al. Aesthetic reconstruction of the tuberous breast deformity. Plast Reconstr Surg 2003;112(4):1099–108; discussion 109. | |

Gao Y, Saksena MA, et al. How to approach breast lesions in children and adolescents. Eur J Radiol 2015;84(7):1350–64. | |

Su PH, Wang SL, et al. A study of anthropomorphic and biochemical characteristics in girls with central precocious puberty and thelarche variant. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2008;21(3):213–20. | |

Soriano Guillen L, Argente J. Peripheral precocious puberty: clinical, diagnostic and therapeutical principles. An Pediatr (Barc) 2012;76(4):229; e1–10. | |

Mareti E, Vatopoulou A, et al. Breast Disorders in Adolescence: A Review of the Literature. Breast Care (Basel) 2021;16(2):149–55. | |

Dancey A, Khan M, et al. Gigantomastia – a classification and review of the literature. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2008;61(5):493–502. | |

Ameryckx L, Leunen M, Wylock P, et al. Breast problems in children and adolescents. Eur Clinics Obstet Gynaecol 2005;1:151–63. | |

Kupfer D, Dingman D, et al. Juvenile breast hypertrophy: report of a familial pattern and review of the literature. Plast Reconstr Surg 1992;90(2):303–9. | |

Govrin-Yehudain J, Kogan L, et al. Familial juvenile hypertrophy of the breast. J Adolesc Health 2004;35(2):151–5. | |

Touraine P, Youssef N, et al. Breast inflammatory gigantomastia in a context of immune-mediated diseases. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005;90(9):5287–94. | |

Care ACoAH. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 350, November 2006: Breast concerns in the adolescent. Obstet Gynecol 2006;108(5):1329–36. | |

Borges JB, Herter LD, Cardoso AM, et al. In: BOFF RA (ed.) Patologia mamária na infância e adolescência, 2nd edn. São Paulo: LemarGoi, 2022. | |

Banikarim C, Nirupama KS. Mastitis and breast abscess in children and adolescents. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/mastitis-and-breast-abscess-in-children-and-adolescents/print?search=Breast%20infection&source=search_result&selectedTitle=7~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=7; 2022. | |

Richards MK, Goldin AB, et al. Breast Malignancies in Children: Presentation, Management, and Survival. Ann Surg Oncol 2017;24(6):1482–91. | |

Harris JR, Lippman ME, Morrow M, et al. Management of palpable breast tumors 5th edn. Wolters Kluwer Health, 2014. | |

Vargas HI, Vargas MP, et al. Outcomes of surgical and sonographic assessment of breast masses in women younger than 30. Am Surg 2005;71(9):716–9. | |

Sadove AM, van Aalst JA. Congenital and acquired pediatric breast anomalies: a review of 20 years' experience. Plast Reconstr Surg 2005;115(4):1039–50. | |

Valeur NS, Rahbar H, et al. Ultrasound of pediatric breast masses: what to do with lumps and bumps. Pediatr Radiol 2015;45(11):1584–99; quiz 1–3. | |

De Silva NK, Brandt ML. Disorders of the breast in children and adolescents, Part 1: Disorders of growth and infections of the breast. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2006;19(5):345–9. | |

Templeman C, Hertweck SP. Breast disorders in the pediatric and adolescent patient. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2000;27(1):19–34. | |

Jayasinghe Y, Simmons PS. Fibroadenomas in adolescence. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2009;21(5):402–6. | |

Greydanus DE, Matytsina L, et al. Breast disorders in children and adolescents. Prim Care 2006;33(2):455–502. | |

Lee EJ, Chang YW, et al. Breast Lesions in Children and Adolescents: Diagnosis and Management. Korean J Radiol 2018;19(5):978–91. | |

Diehl T, Kaplan DW. Breast masses in adolescent females. J Adolesc Health Care 1985;6(5):353–7. | |

Tea MK, Asseryanis E, et al. Surgical breast lesions in adolescent females. Pediatr Surg Int 2009;25(1):73–5. | |

Chung EM, Cube R, et al. From the archives of the AFIP: breast masses in children and adolescents: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics 2009;29(3):907–31. | |

Joshi SC, Sharma DN, et al. Cystosarcoma phyllodes: our institutional experience. Australas Radiol 2003;47(4):434–7. | |

Gutierrez JC, Housri N, et al. Malignant breast cancer in children: a review of 75 patients. J Surg Res 2008;147(2):182–8. | |

Kamitani T, Matsuo Y, et al. Differentiation between benign phyllodes tumors and fibroadenomas of the breast on MR imaging. Eur J Radiol 2014;83(8):1344–9. | |

Linell F, Ostberg G, et al. Breast hamartomas. An important entity in mammary pathology. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histol 1979;383(3):253–64. | |

Fisher CJ, Hanby AM, et al. Mammary hamartoma – a review of 35 cases. Histopathology 1992;20(2):99–106. | |

Georgian-Smith D, Kricun B, et al. The mammary hamartoma: appreciation of additional imaging characteristics. J Ultrasound Med 2004;23(10):1267–73. | |

Chang HL, Lerwill MF, et al. Breast hamartomas in adolescent females. Breast J 2009;15(5):515–20. | |

Rosen PP, Holmes G, et al. Juvenile papillomatosis and breast carcinoma. Cancer 1985;55(6):1345–52. | |

Gill J, Greenall M. Juvenile papillomatosis and breast cancer. J Surg Educ 2007;64(4):234–6. | |

Olarinoye-Akorede SA, Farouk B, et al. Giant juvenile papillomatosis of the breast in a Nigerian girl. BMJ Case Rep 2018;11(1). | |

Rogers DA, Lobe TE, et al. Breast malignancy in children. J Pediatr Surg 1994;29(1):48–51. | |

Johnson RH, Chien FL, et al. Incidence of breast cancer with distant involvement among women in the United States, 1976 to 2009. JAMA 2013;309(8):800–5. | |

Bower R, Bell MJ, et al. Management of breast lesions in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Surg 1976;11(3):337–46. | |

Pryor LS, Lehman JA Jr, et al. Disorders of the female breast in the pediatric age group. Plast Reconstr Surg 2009;124(1 Suppl):50e–60e. | |

National Cancer Institute. Cancer of the Breast (Invasive): SEER Incidence and US Death Rates, Age-Adjusted and Age-Specific Rates, by Race and Sex. Available from: www.seer.cancer.gov. | |

Hodgson D vLF, Ng A, et al. Breast cancer after childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer: It's not just about chest radiation. 2018. Available from: https://meetinglibrary.asco.org/record/138307/edbook#fulltext. | |

Yeh JM, Lowry KP, et al. Clinical Benefits, Harms, and Cost-Effectiveness of Breast Cancer Screening for Survivors of Childhood Cancer Treated With Chest Radiation: A Comparative Modeling Study. Ann Intern Med 2020;173(5):331–41. | |

Corpron CA, Black CT, et al. Breast cancer in adolescent females. J Pediatr Surg 1995;30(2):322–4. | |

Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast C. Familial breast cancer: collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 52 epidemiological studies including 58,209 women with breast cancer and 101,986 women without the disease. Lancet 2001;358(9291):1389–99. | |

Levine AJ. The p53 tumor-suppressor gene. N Engl J Med 1992;326(20):1350–2. | |

Elger BS, Harding TW. Pediatric forum: genetic testing of adolescents: is It in their best interest? Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2000;154(8):850–2. | |

Network NCC. 2022. Available from: www.nccn.org. | |

Sanders LM, Sharma P, et al. Clinical breast concerns in low-risk pediatric patients: practice review with proposed recommendations. Pediatr Radiol 2018;48(2):186–95. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards programme CLICK HERE)