This chapter should be cited as follows:

Cizek S, Fluharty E, et al., Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.418293

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Gynecology Module

Volume 2

Adolescent gynecology

Volume Editor: Professor Judith Simms-Cendan, University of Miami, USA

Chapter

Differences of Sex Development (Intersex) Care

First published: October 2022

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

INTRODUCTION

Differences of Sex Development (DSD) refers to a diverse group of congenital conditions within which the development of chromosomal, gonadal, or anatomic sex is atypical (see Box 1 for examples of conditions). This chapter discusses the diagnosis and management of DSD conditions within a multidisciplinary, patient-centered care approach. These patients have specialized and often complex care needs.

Box 1 Conditions Commonly Classified as DSD (Modified from the 2006 Consensus Statement)1

46,XY

- Disorders of gonadal development (e.g., ovotesticular DSD, gonadal dysgenesis)

- Disorders of androgen synthesis (e.g., androgen biosynthesis defects, congenital adrenal hyperplasia)

- Disorders of androgen action (androgen insensitivity)

- Persistent Mullerian Duct Syndromes

- Unclassified (e.g., hypospadias)

46,XX

- Disorders of gonadal development (e.g., ovotesticular DSD, some primary ovarian insufficiency)

- Disorders of androgen synthesis (e.g., aromatase deficiency, congenital adrenal hyperplasia)

- Unclassified (e.g., Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome)

Sex chromosomal

- Turner syndrome

- Klinefelter syndrome

- Mixed gonadal dysgenesis

- Chimerism

TERMINOLOGY

The term DSD was put into common use with the 2006 Consensus Statement,1 and initially stood for “Disorder of Sex Development.” This terminology sought to replace terms like hermaphroditism, reverse sex, and other terms which are pejorative and medically vague. The authors of this chapter want to recognize and respect the self-identification of patients, including the acknowledgement that some people do not identify with the term DSD,2,3 and that terminology is evolving and imperfect (for example, intersex is sometimes used synonymously with DSD but sometimes refers to more specific conditions, and is also not universally accepted by patients). For the purposes of this chapter, DSD will be used to mean Differences of Sex Development and is mainly used to describe a group of diagnoses that may benefit from the multi-disciplinary care detailed below; in patient interactions, a patient’s own terminology preferences, as well as specific care needs, should be established and respected. It should be noted that identification as transgender or another gender non-conforming identity is not a pathology and is not considered a DSD.

MULTI-DISCIPLINARY CARE APPROACH

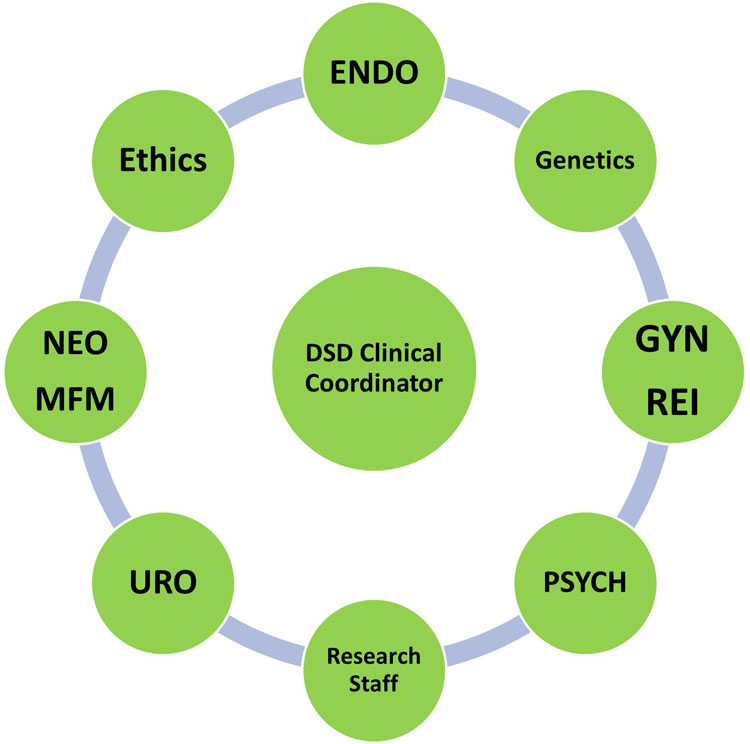

The care of patients with DSD’s may be complex, and patients frequently require support and expertise from a variety of specialists. To meet these needs, the current model of care is with a multidisciplinary approach1 (see Figure 1). This chapter was written as a collaboration between our subspecialists in our multidisciplinary clinic, in part for each specialist to provide their own expertise, and in part to demonstrate how a collaborative care model can be used to provide the best support for patients.

1

An example of a multidisciplinary model for DSD care. Endo, pediatric endocrinology; NEO, neonatology and neonatal intensive care unit providers; MFM, maternal-fetal medicine; Uro, pediatric urology; Psych, psychiatry; GYN, pediatric Gynecology; REI, reproductive endocrinology and infertility.

NEONATOLOGY: PERINATAL DSD MANAGEMENT

Elizabeth Fluharty, MS, NNP, Karina Talreja, MS, LCGC, and Nicole Weigel, MS, NNP

Fetal and Pregnancy Health Program at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital

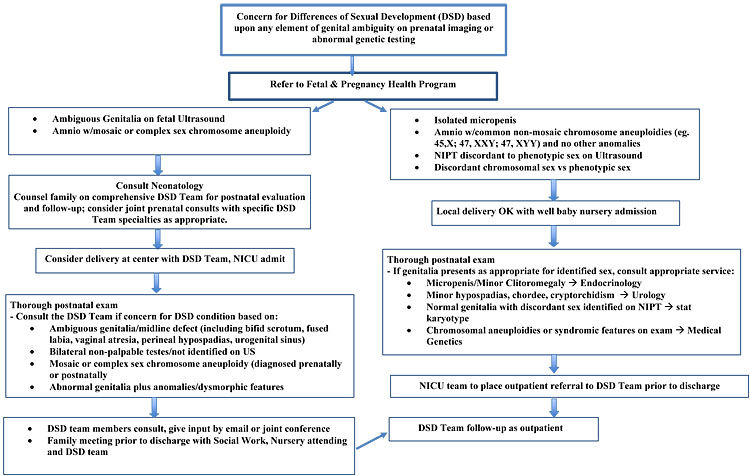

The expectant parent is often eager to learn the fetal sex, anticipating a simple declaration of “boy” or “girl.” When sex identification is not straightforward, further testing, imaging, and counseling is warranted. Multidisciplinary, coordinated care for these families for whom a possible DSD is identified prenatally includes a complete diagnostic evaluation and prenatal subspecialty consultations to assure a smooth transition between pre- and postnatal care.

Prenatal identification of a patient with a DSD may occur upon ultrasound finding of ambiguous genitalia (genitalia that is not “typical” for either male and female phenotypes),4 genetic testing revealing a mosaic or complex sex chromosome aneuploidy, or an identified discrepancy between the chromosomal genotype with genital phenotype. Once identified, within our care model a Fetal Program referral is placed, prompting the initial steps of genetic counseling and further diagnostic testing. Prenatal genetic counseling should include a detailed pregnancy and family history to exclude androgen exposure and/or familial syndromes. Prenatal genetic testing recommendations often include amniocentesis with FISH for sex chromosomes, FISH for SRY, karyotype, chromosomal microarray, single gene studies (e.g., congenital adrenal hyperplasia), or gene panels.5,6

Consultations with Maternal Fetal Medicine, Neonatology, and Psychiatry are critical in assuring the family is well-supported in the understanding of diagnostic results and the anticipated neonatal care. When appropriate, these consultations may also include other members of the DSD team. A discussion of planned sex of rearing may start prenatally and continue in the neonatal period, which is a stressful and uncertain discussion that requires experienced psychologic support; in addition, during this time the care providers should be very careful to avoid gendered pronouns or prematurely designating sex.1,4 The neonatal plan often includes NICU admission for a thorough physical exam, laboratory evaluation, a pelvic ultrasound to evaluate anatomy, and consultation by DSD team members as clinically indicated. Additional neonatal, genetic and/or endocrine evaluation may be pursued depending on prenatal diagnostics and neonatal presentation. Throughout the neonatal hospitalization, the family is encouraged to ask questions, participate in neonatal care, and supported through complex discussions. At time of hospital discharge, outpatient follow-up is arranged in the multidisciplinary DSD clinic.

See Figure 2 for an example of our own institutional protocol.

2

Fetal to Neonatal Care Algorithm.

PSYCHIATRY: PSYCHOLOGICAL CONSULTATION IN THE DSD CLINIC

Miriam B. Muscarella, MD and Richard J. Shaw, MD

The diagnosis of a genetic or developmental disorder, whether prenatally or later in the course of the child’s life, is a profound and often life-changing event for a family. It is often a traumatic event for parents, and one associated with grief as they grapple with the loss of the fantasy of having a “perfect” child. In the case of a child diagnosed with a DSD condition, both parents and child are at greater risk of difficulties with social adjustment, including symptoms of anxiety and depression, as they deal with stigma and isolation.7 In recognition of these issues, the Consensus Statement on Management of Intersex Disorders1 has emphasized the importance of the role of psychosocial care in the multidisciplinary team management of children with DSD diagnoses. Recommendations have included the use of psychosocial screenings to identify families at risk for maladaptive coping.1 In addition, the importance of a developmental approach has been recognized, taking into account that each phase of the child’s development has the potential to raise new challenges that may require targeted psychosocial interventions.

Role of the Psychological Consultant

Since each family and patient has a unique way of learning about their specific variation, the psychological consultant (psychiatrist/psychologist/social worker) should help foster a holistic view of the learning journey underway with a family and their child. This role involves themes of providing and promoting: psychological support and treatment for patients and parents, holistic understandings, addressing quality of life concerns, and identifying biologic, psychologic, and sociologic factors that impact psychological health in DSD patients.8 Practically, this work involves understanding the initial diagnosis journey and related joys and stresses of that experience. It includes evaluation of mental health (issues of adjustment, anxiety, depression), understanding of the individual variation, and conceptualizing developmental components that enrich an understanding of how the team can best approach individual and family support, coping, and growth. An overarching goal of the psychosocial team is to build self-efficacy of the patient and family in communicating needs and making use of support.

When a youth and family is considering potential intervention, the psychological consultant helps to build the model of informed consent and work with a youth to build a capacity to make medical decisions (including the decision to not have specific interventions), and to foster self-determination and self-advocacy. This approach places the youth as the guide for the care environment. As youth and family get older, this role augments psychoeducation around sexuality, psychosexual concerns, and intimacy. The team bears witness to and provides support for journeys around identity (fertility possibilities, sex, gender, and sexuality) that span the life course.

Resources

Domains to be considered in the psychological evaluation in DSD include quality of life, psychological functioning, personality and identity, sexuality and sexual functioning, body image, social support, and life satisfaction.9 Although there is a lack of empirically validated DSD-specific screening tools, our DSD team utilizes the DSD Concerns' Scale10 that is available in a patient and parent report format to identify common concerns, and also to normalize these issues for new patients and families (see Table 1).

1

Questions included in the DSD Concerns' Scale.

Concerns about body or health | Appearance of genitals Internal reproductive anatomy Ability to urinate in a typical way Need for medications Physical growth or development School performance/ability to learn |

Reactions of others | Reactions of family members Reactions of friends Reactions of babysitters/childcare providers Reactions of people at school People feeling sorry for patient/family People talking about the condition People avoiding patient/family Being teased Being excluded from social activities |

Worries about the future | Worries about being teased Worries about being treated differently Worries about being unhappy Worries about puberty Worries about being able to have sex Worries about not being able to have children Worries about being able to be in a relationship Worries about sexual orientation Worries about gender identity Worries about needing surgery Worries about people finding out about DSD condition Worries about cancer or other illness |

The psychosocial team also provides youth-friendly or parent-friendly websites or peer-to-peer resources that include www.dsdteens.org for youth and www.dsdfamilies.org for families. These websites provide support group information, and offer important and accessible psychoeducation regarding sex and puberty education. We also recommend getting support from other clinics serving similar families/patients and exploring shared resources/supports, as in the Differences of Sex Development–Translational Research Network (www.dsdtrn.org) and the Lend a Helping Hand handbook created by Accord Alliance with the DSD-TRN containing comprehensive information on current patient and provider resources (www.accordalliance.org/resource-guide/).

GENETICS

Heather Byers, MD and Brooke Dunleavy, MS, LCGC

Genetics' evaluation plays a key role in evaluating patients with DSD conditions. Genital differences can be seen in hundreds of genetic syndromes, or can be isolated; an examination by a geneticist typically starts by assessing if the anatomic, gonadal or hormonal discordance are more likely an isolated finding or as part of a larger genetic syndrome or sequence.11 A geneticist may also assist with clinical diagnosis of non-genetic etiologies, such as a teratogen exposure. Obtaining a genetic diagnosis for the patient can inform medical management and expected prognosis – and may provide insight to key decision points such as sex of rearing, gonadoblastoma risk, family recurrence risk, and fertility outcomes.

A karyotype (+/− FISH for SRY gene) is a key first step and can help determine which category of DSD the patient falls under (46,XX DSD, 46,XY DSD or other chromosomal aneuploidy) and direct further evaluation; this test is typically ordered as soon as possible. Additional genetic assessment and testing is typically recommended for patients in whom chromosomal assessment, physical examination, and/or endocrine evaluation do not yield a definitive diagnosis.11 Complex genetic testing may involve considerations involving cost/insurance coverage and longer turnaround times; however, as the cost and turnaround time for more comprehensive genetic testing decreases, sequencing such as exome sequencing are increasingly employed sooner, including first line after chromosomal assessment. In considering further genetic testing, various approaches may be considered. In some cases, physical examination or endocrine evaluation will suggest a specific diagnosis, and a targeted test can be ordered. If not, chromosomal microarray assesses for copy number variants that are too small to be detected on karyotype and can give more precise breakpoints in a deleted or duplicated aspect of a chromosome. Although microarray will also assess the SRY gene, FISH for the SRY gene can be useful in cases that require a quick turnaround time, or where the concern is for chromosomal sex DSD, including low-level mosaicism. Genetic “panels” utilize next-generation sequencing to simultaneously examine a group of genes associated with a clinical phenotype and are often cost-effective with a quick turnaround time.11 If a diagnosis is not achieved, re-analysis can be performed as time passed and if important additional phenotypic features are appreciated as the child grows and develops.11

While genetic testing can aid in diagnosis, genetic counseling is equally important for education of the patient, family, and other health care providers. Genetic counselors have advanced training in medical genetics and counseling to guide and support patients seeking more information about how to interpret genetic test results, and how inherited diseases and conditions might affect them or their families. A genetic counselor often becomes a touch-point for the family given their skilful ability to provide both psychosocial and medical education support. As advanced genetic technology, such as exome sequencing, becomes more commonly integrated into diagnostic workup for patients with DSD, the diagnostic yield of genetic testing for DSD conditions has improved.12 Having a diagnosis can help to guide medical management, but also gives patients an understanding of their differences and prognosis, which can aid in building their identity or support system. While diagnosis has improved with genetic testing, uncertain variants are also commonly reported on exome or gene panels' testing. These variants can be confusing to families and non-genetics professionals who may incorrectly assume the significance of such variants, and genetic counseling can ensure these variants are discussed correctly with the family and care team. Lastly, genetic counseling provides patients and families with the opportunity to understand the risk of recurrence and identify other individuals in the family who may be at risk, so that they can make informed decisions regarding their reproductive health. Genetic counselors in a DSD clinic educate families on basic genetics' concepts, so that patients understand why testing is being offered, the results of recommended tests and their implications, to hopefully help patients feel empowered to be a part of the decision-making process regarding medical-management decisions.

ENDOCRINOLOGY

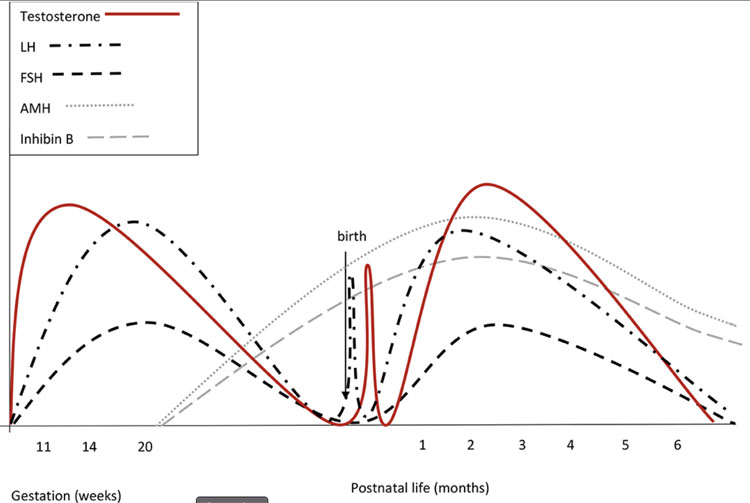

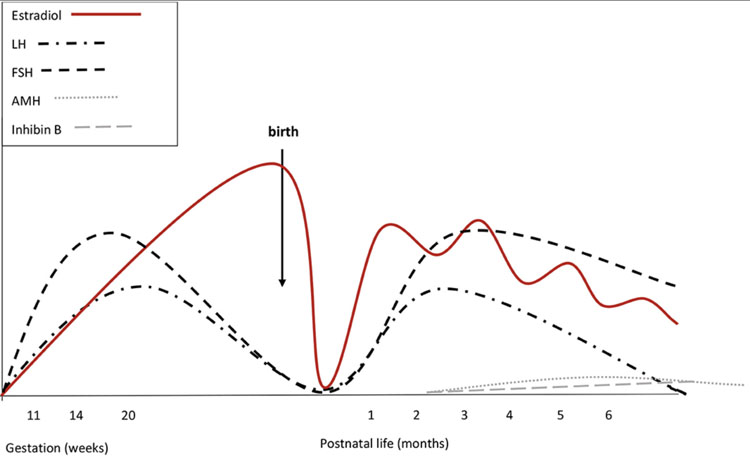

Hilary Seeley, MD

There are three distinct periods of hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis activation during human development: pre-natal, mini-puberty of infancy and adolescence (see Figures 3 and 4).13,14 These periods provide distinct windows to interpret an individual’s endogenous hormone production and response.

The first period of HPG activation occurs during fetal development in utero between the 10th and 24th weeks of gestation.14 In the male fetus, testosterone peaks in the first trimester of pregnancy (11th to 14th week of gestation) and dihydrotestosterone (DHT) is responsible for development of male external genitalia. In the female fetus, estradiol peak is seen in the third trimester of pregnancy, derived mostly from the placenta.14 Although declining from peak levels earlier in pregnancy, the first 24 hours of life can be an opportunity to capture a hormone profile from the uterine environment.

The second period of HPG activation (often called “mini-puberty”) occurs during infancy, typically in the first 1–6 months of life.14 Gonadotropins (Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle Stimulating Hormone (FSH)) levels begin to rise in the weeks after birth. LH levels are higher in boys than in girls, peaking at 2–10 weeks of life. This LH surge stimulates testosterone production, peaking in the 2nd–3rd month of life (reaching levels of adult men) and decreasing to pre-pubertal levels by 6 months of age. Estradiol levels are higher in girls than in boys (reaching levels of near adult women). FSH levels are higher in girls than in boys and often remain higher until 3–4 years of age, whereas in boys decrease by 6 months of age.

The third period of HPG activation occurs during adolescence, typically between age 8 and 13 years for girls and between 9 and 14 years for boys.14 This process induces physical pubertal changes and the capacity for reproduction.

Biochemical markers for evaluation of a suspected DSD condition include LH, FSH, testosterone, dihydrotestosterone (DHT), estradiol, 17-hydroxy progesterone (hormone panel for congenital adrenal hyperplasia if indicated), anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) and inhibin b. Markers specific for evaluation of testicular tissue are LH, FSH, testosterone, AMH, and inhibin b. Provocative tests such as cosyntropin (synthetic ACTH) or beta hCG may be indicated in certain circumstances.

Physical examination is central to diagnostic evaluation of individuals with suspected DSD conditions. In the newborn period, location of gonads and degree of virilization of genitalia are important features. The anogenital ratio is a specific measurement used to describe the degree of prenatal virilization.15 In adolescence, development of breasts, virilization of genitals and growth curve can inform which studies are most helpful.

Laboratory investigations play a key role in the diagnostic evaluation of individuals with suspected DSD conditions. Establishing the diagnosis is essential to counseling on the likelihood of endogenous hormone production, physical response to hormones and fertility. Measuring sex hormone levels is helpful during three time periods: immediate post-natal period, mini-puberty of infancy, and puberty of adolescence.

3

Hormonal fluctuations in males. (Reproduced from Bizarri and Cappa, 202016 – open access resource.)

4

Hormonal fluctuations in females. (Reproduced from Bizarri and Cappa, 202016 – open access resource.)

UROLOGY AND GYNECOLOGY: ANATOMIC, SEXUAL HEALTH, AND SURGICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Stephanie Cizek, MD

Neonatal Care

Urology is often consulted acutely in the neonatal setting to evaluate for medical problems such as evidence of urinary obstruction or other urinary problems. Gynecology and Urology teams often work together to understand a patient’s anatomy, as this time period represents an opportunity to assess structures that may not be as visible later. Early imaging can be revealing of uterine and ovarian structures in the first 6 months of life due to maternal stimulation and mini-puberty effect.13 After this, it is common to have nonvisualization of these structures on ultrasound or even magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) until the patient reaches the age of their own pubertal stimulation. While many future questions (future pubertal development, future sexual and fertility function, etc.) often remain unknown in this time period, this also represents an opportunity to establish partnered relationships with families, and to impress that these aspects of care will continue to be considered and addressed over time.

Sexual Health Care

Gynecologists and urologists are uniquely trained to assess and manage sexual health problems and to discuss sexual health concerns. Routine adolescent care includes confidential interviews to determine if a patient has any gender identity questions, sexual health concerns, contraception needs, sexually transmitted infection screening needs, or fertility questions.17 As discussed in the Psychiatry section above, gender and sexual health are another example of care that is delivered in developmentally appropriate ways. Questions from a patient about their own health will change over time, and older patients will often desire review of their diagnosis and anatomy at different stages of their life. Anatomic limitations may preclude desired sexual function; for example, some people with urogenital sinus may have a very narrowed opening that precludes vaginal sexual activity. Post-operative surgical sexual health complications may be present for patients who had previously undergone genitoplasty, such as clitoral pain or reduction in sensation, cosmetic concerns, or vaginal stenosis, and these should be addressed and managed.18

Surgical Care

There has been in the past an emphasis on genital surgery for patients with ambiguous genitalia, and on gonadectomy to reduce malignancy risk; often these surgeries were done before a patient themselves had any input in decision-making. Surgery choices and recommendations for timing of surgery have changed to incorporate the patient, family, and members of the multi-disciplinary team in a patient-centered decision-making approach. This change over time is due to both an ethical emphasis on prioritizing patient autonomy, and medical changes in knowledge including changes in our understanding of malignancy risk for certain DSD conditions.

Box 2 Examples of Surgical Considerations

- Ethical (e.g., patient autonomy, parental decision-making, open future, beneficence, non-maleficence)

- Patient gender identity and sexual preferences

- Patient/family beliefs, culture

- Timing of surgery (immediate, delayed, never)

- Indication for surgery (medical, cosmetic, sexual function, tumor prevention)

- Patient anatomy (e.g., location of gonads, length of urogenital sinus, degree of virilization)

- Surgical technique planned

- Known and unknown surgical risks (surgical complications, cosmetic outcomes)

- Known and unknown risks of delaying/deferring surgery (tumor risk, psychosocial outcomes)

- Hormone potential (gonadal surgery)

- Legal (institutional, local, and national)

Genital Surgery: Genital surgery aims to (a) address medical problems such as urinary tract obstruction or infections, and/or (b) allow for vaginal use for sexual activity or vaginal menstrual hygiene products, and/or (c) alter the cosmetic appearance of the external genitalia to be aligned with more typically male or more typically female appearance. Early surgery to reduce the size of the clitorophallus often involved clitoridectomy. Surgery technique has thankfully evolved over time, but comparative data on surgical techniques and outcomes are lacking and vary widely. For example, a 2014 study of patients with prior feminizing genitoplasty involving vaginal surgery found that 79% of patients had some degree of vaginal stenosis (17% had totally absent vagina),19 but only 8% had vaginal stenosis in a 2020 study with a 12 month follow-up period.20 It should also be noted that there is a lack of data on long-term sexual, psychosocial, and urologic outcomes for patients who choose not to have surgery. Patient retrospective input on timing of surgery has been a main driver towards re-focusing the decision-making, appropriately, on patient autonomy, although there remains no clear consensus on a single “correct” timing of surgery for all patients (if surgery is done at all). A 2011 study of patients aged 15–39 years old who had genitoplasty and/or vaginoplasty at a median age of 2.1 years indicated that 70% of patients felt that the timing of their surgery was correct.21 On the other hand, in 2017 two advocacy groups authored a statement urging a moratorium on surgical procedures that would alter the gonads, genitals, or internal sex organs of young children with atypical characteristics.22 At present, many medical societies involved in the care of DSD patients, including the Societies for Pediatric Urology, the North American Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Endocrinology, and the Pediatric Endocrine Society, advocate for a highly individualized approach and support delaying surgery when safe for the patient.

Gonadectomy: Gonadectomy aims primarily to reduce the risk of malignancy posed by abnormally differentiated gonadal tissue. Another goal for some patients may be to remove sex-hormone production that may not be aligned with a patient’s gender identity. Examples of factors to consider that are specific to gonadectomy include the following:

- Malignancy risk: There is varying tumor risk by condition, and intrabdominal gonads typically carry higher risks of malignancy compared to inguinal or scrotal gonads.23

- Hormone potential: While dysgenetic gonads may decrease in function over time, some may produce normal sex hormones. Labs done at mini-puberty (ideally drawn between 2 and 4 months of life) may indicate future hormone production type and potential. For example, elevated FSH and/or AMH and Inhibin B levels that are below normal range for sex in infancy or puberty suggest gonadal insufficiency; these labs together with sex hormones (testosterone, estradiol) can also give information on whether the gonad contains functional testicular vs. ovarian tissue.

- Monitoring of gonad or risk-reduction techniques: There is no reliable way to monitor the gonads for malignancy or precursor tumor over time. Intra-abdominal gonads cannot be monitored with palpation, and palpation of gonads is not a reliable way of monitoring for malignancy (for example, for cis-male patients with typical scrotal testes, testicular self-palpation is not recommended to reduce testicular cancer risk). Surgical pexy of the gonad into a palpable location (such as pexy of a testicle into the inguinal canal) may be feasible in select patients, but with unclear benefit. Imaging (ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging) has been shown to miss cases of precursor lesions or even overt malignancy.24 Serum gonadal tumor markers are often negative even in the setting of overt malignancy and are not reliable for monitoring. The only way to eliminate the risk of germ-cell malignancy is with gonadectomy.

- Fertility potential: This also varies by DSD condition. Gonadectomy without fertility preservation removes any possibility of fertility potential. While fertility preservation may be unlikely for certain DSD conditions, Finlayson et al. 201725 examined experimental gonadal tissue freezing in patients with DSD conditions and found gonadocytes even in tissue that was not thought to have any fertility potential, such as a streak gonad. This technology is currently in its infancy and there are many unknowns between finding gonadocytes and using this tissue to obtain a live birth.

Gender identity and sexual preferences are points to consider for either genital or gonadal surgery. For example, a patient may desire external genitalia and internal reproductive structures to align with gender identity, and having a vagina for future vaginal sexual activity should not be assumed to be a goal for all females. For gonads, retaining hormonally functional gonads is most helpful if it provides a hormone that is aligned with the patient's gender identity. Allowing a patient’s gender identity and sexual preferences to develop takes time, and is a factor that favors delaying surgery to allow patient input when possible.

Legal and Policy Considerations: Genital surgery involving minors has varying restrictions in different countries or by states/regions within a country. Knowledge of local and national laws and regulations is important. Different hospitals may also have their own policies regarding genital surgeries in minors.

Ethical and Cultural Considerations: Both genital and gonadal surgery represent complex ethical decisions and it is recommended that a team-based approach be used to help patients, families, and providers understand the factors involved in decision-making for an individual patient. Patient autonomy and the patient’s right to an open future (the right to future autonomous decisions and opportunities) should be a primary factor in decision-making.26 For young children, the parental right to make decisions for their own child must be carefully balanced with patient autonomy, particularly as a patient reaches the age of assent or legal consent.26 Patient and family culture and beliefs also play important roles in decision-making: every individual patient/family unit presents different perspectives, and may view risk data (such as risk of malignancy if gonads are retained, psychosocial risks of delaying genital surgery, or surgical complication risks) differently. Decision-making support for patients and families should, at a minimum, include medical team members, longitudinal psychologic support for patients and families, and inclusion of an ethicist in decision-making if appropriate. Resources for patient and family support networks and organizations should be provided, and some families may desire additional supports such as chaplaincy consultation, or need additional resources for which social work involvement may be appropriate.

The many factors to consider and the deeply personal nature of these factors demonstrates the importance of multi-faceted support for patients and families making these decisions, including multi-disciplinary medical and psychologic care and connection to peer and family support groups whenever possible.

FERTILITY – DSD FERTILITY PRESERVATION

Brindha Bavan, MD

Fertility preservation counseling for DSD patients is an important, evolving field that incorporates reproductive science, advancing technology, and ethical considerations. There are often multiple shareholders’ perspectives to consider, including the patient, parent/guardian, and a multidisciplinary medical team. Early conversations regarding reproductive potential and available family building options with a fertility specialist are beneficial.27,28 At the same time, these conversations can be overwhelming, thus it is important to gauge the level of receptiveness and need for regular follow up. Additionally, rather than sex assignment without patient assent/consent, patients are encouraged to explore their gender identity so it can inform their decision-making with regard to personal sexual health and fertility goals.

A patient’s specific DSD diagnosis, genetic testing, and available reproductive anatomy/physiology all inform fertility preservation options (see Table 2). If a patient has functional gonads, gamete provision is possible through natural conception or oocyte/sperm/embryo cryopreservation. If not, donor gametes are available through known donors (family members/friends) or anonymous donor banks.

- For individuals who require prepubertal gonadectomy for malignancy risk reduction, in some cases there are options for ovarian/testicular tissue cryopreservation with the hope that future technological advances will allow for gamete derivation.29 This is experimental, however, and postpubertal autologous gametes or donor gametes have shown the highest success rates for conception in these patients currently.

- If a patient has a uterus (and does not have a medical preclusion to conception such as major cardiac risk in Turner syndrome patients), carrying a gestation oneself is possible following uterine size/lining development with either endogenous or exogenous hormone exposure with estrogen and progesterone. If not, a gestational carrier or partner may be utilized. Research developments are being made in the field of uterine transplantation as well, and this may be an option for more patients in the future.

- Unfortunately, the cost burden of these treatments can limit access to care. It is important to be comprehensive when counseling and to review alternatives such as adopting or choosing not to raise children.

2

Fertility preservation options in select conditions. (Modified from Alur-Gupta et al. 2021 and Finlayson et al. 2022.)30,31 It should be noted that people with DSD diagnoses may have variations in gonadal anatomy or function that can vary from above.

DSD condition | Functional uterus present? | May have sperm? | May have oocytes? | Fertility preservation (FP) options |

46,XY Complete gonadal dysgenesis (Swyer syndrome) | Yes | No | No | No functional gonadal tissue, FP not possible |

46,XX and 46,XY Ovotesticular DSD | Yes | Yes | Yes | FP depends on type/function of gonadal tissue |

Mixed gonadal dysgenesis | No | Yes | No | May have germ cells, gonadocyte cryopreservation is experimental |

Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome | No | No | Yes | Oocyte cryopreservation with use of gestational carrier, experimental uterine transplant |

46,XX Congenital adrenal hyperplasia | Yes | No | Yes | Fertility problems vary based on severity, glucocorticoid treatment can help normalize pituitary-ovarian axis |

Androgen insensitivity | No | No (complete), Yes (partial) | No | FP options vary by phenotype |

CONCLUSION

Care for patients with DSD involves expertise from many disciplines, which requires excellent care coordination and communication. The focus should always be primarily on the patient and their immediate and future needs, with developmentally appropriate management to foster health, independence, and confidence for our patients and their families.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- A multidisciplinary care approach is recommended for the care of patients with Differences of Sex Development, including in the prenatal period if a DSD diagnosis is suspected.

- Psychologic care is critical for both patients and their families starting from the time that a DSD condition is first suspected, and longitudinal support for patients should be provided using age and developmental milestones to guide care.

- Genetic testing may aid with both diagnostic and prognostic information, and should always be accompanied by genetic counseling,

- Endocrine testing can be most informative in the time of mini-puberty of infancy or during adolescence, and can provide both diagnostic information and assess hormone/gonadal function.

- Surgical management should be determined with a shared decision-making model that includes the patient’s input whenever possible, which may mean that some surgeries should be delayed so that the patient is able to participate in decision-making.

- Confidential conversations between patients and providers are an important aspect of all adolescent health care, including for patients with DSD conditions, to allow discussions of gender identity, sexual health, contraceptive needs, etc.

- Fertility potential should be reviewed with every patient and fertility preservation should be considered whenever possible.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) of this chapter declare that they have no interests that conflict with the contents of the chapter.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

REFERENCES

Lee PA, Houk CP, Ahmed SF, Hughes IA, International Consensus Conference on Intersex organized by the Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society and the European Society for Paediatric Endocrinology. Consensus statement on management of intersex disorders. International Consensus Conference on Intersex. Pediatrics 2006;118(2):e488–500. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-0738. | |

Lin-Su K, Lekarev O, Poppas DP, et al. Congenital adrenal hyperplasia patient perception of “disorders of sex development” nomenclature. Int J Pediatr Endocrinol 2015;2015(1):9. doi:10.1186/s13633-015-0004-4. | |

Johnson EK, Rosoklija I, Finlayson C, et al. Attitudes towards “disorders of sex development” nomenclature among affected individuals. J Pediatr Urol 2017;13(6):608.e1–8. doi:10.1016/j.jpurol.2017.03.035. | |

Stambough K, Magistrado L, Perez-Milicua G. Evaluation of ambiguous genitalia. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2019;31(5):303–8. doi:10.1097/GCO.0000000000000565. | |

Smet ME, Scott FP, McLennan AC. Discordant fetal sex on NIPT and ultrasound. Prenat Diagn 2020;40(11):1353–65. doi:10.1002/pd.5676. | |

Narasimhan ML, Khattab A. Genetics of congenital adrenal hyperplasia and genotype-phenotype correlation. Fertil Steril 2019;111(1):24–9. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.11.007. | |

Wisniewski AB, Sandberg DE. Parenting Children with Disorders of Sex Development (DSD): A Developmental Perspective Beyond Gender. Horm Metab Res 2015;47(5):375–9. doi:10.1055/s-0034-1398561. | |

Ravendran K, Deans R. The Psychosocial Impact of Disorders of Sexual Development. J Sexual Med Reprod Health 2019;2(4). | |

D’Alberton F, Vissani S, Ferracuti C, Pasterski V. Methodological Issues for Psychological Evaluation across the Lifespan of Individuals with a Difference/Disorder of Sex Development. Sex Dev 2018;12(1–3):123–34. doi:10.1159/000484189. | |

Shaw RJ. DSD Concerns Scale. Stanford University 2021. Published online 2021. | |

Byers HM, Fossum M, Wu HY. How geneticists think about Differences/Disorders of Sexual Development (DSD): A conversation. J Pediatr Urol 2020;16(6):760–7. doi:10.1016/j.jpurol.2020.08.015. | |

Baxter RM, Arboleda VA, Lee H, et al. Exome sequencing for the diagnosis of 46,XY disorders of sex development. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015;100(2):E333–44. doi:10.1210/jc.2014-2605. | |

Lucaccioni L, Trevisani V, Boncompagni A, et al. Minipuberty: Looking Back to Understand Moving Forward. Front Pediatr 2020;8:612235. doi:10.3389/fped.2020.612235. | |

Becker M, Hesse V. Minipuberty: Why Does it Happen? Horm Res Paediatr 2020;93(2):76–84. doi:10.1159/000508329. | |

Sathyanarayana S, Grady R, Redmon JB, et al. Anogenital distance and penile width measurements in The Infant Development and the Environment Study (TIDES): methods and predictors. J Pediatr Urol 2015;11(2):76.e1–6. doi:10.1016/j.jpurol.2014.11.018. | |

Bizzarri C, Cappa M. Ontogeny of Hypothalamus-Pituitary Gonadal Axis and Minipuberty: An Ongoing Debate? Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2020;11:187. doi:10.3389/fendo.2020.00187. | |

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Adolescent Health Care. The Initial Reproductive Health Visit: ACOG Committee Opinion, Number 811. Obstet Gynecol 2020;136(4):e70–80. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000004094. | |

Wang LC, Poppas DP. Surgical outcomes and complications of reconstructive surgery in the female congenital adrenal hyperplasia patient: What every endocrinologist should know. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2017;165(Pt A):137–44. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2016.03.021. | |

Michala L, Liao LM, Wood D, et al. Practice changes in childhood surgery for ambiguous genitalia? J Pediatr Urol 2014;10(5):934–9. doi:10.1016/j.jpurol.2014.01.030. | |

Baskin A, Wisniewski AB, Aston CE, et al. Post-operative complications following feminizing genitoplasty in moderate to severe genital atypia: Results from a multicenter, observational prospective cohort study. J Pediatr Urol 2020;16(5):568–75. doi:10.1016/j.jpurol.2020.05.166. | |

Fagerholm R, Santtila P, Miettinen PJ, et al. Sexual function and attitudes toward surgery after feminizing genitoplasty. J Urol 2011;185(5):1900–4. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2010.12.099. | |

InterACT, Human Rights Watch (Organization), eds. “I Want to Be like Nature Made Me”: Medically Unnecessary Surgeries on Intersex Children in the US. Human Rights Watch, 2017. | |

Looijenga LHJ, Hersmus R, Oosterhuis JW, et al. Tumor risk in disorders of sex development (DSD). Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007;21(3):480–95. doi:10.1016/j.beem.2007.05.001. | |

Ebert KM, Hewitt GD, Indyk JA, et al. Normal pelvic ultrasound or MRI does not rule out neoplasm in patients with gonadal dysgenesis and Y chromosome material. J Pediatr Urol 2018;14(2):154.e1–6. doi:10.1016/j.jpurol.2017.11.009. | |

Finlayson C, Fritsch MK, Johnson EK, et al. Presence of Germ Cells in Disorders of Sex Development: Implications for Fertility Potential and Preservation. J Urol 2017;197(3 Pt 2):937–43. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2016.08.108. | |

Harris RM, Chan YM. Ethical issues with early genitoplasty in children with disorders of sex development. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 2019;26(1):49–53. doi:10.1097/MED.0000000000000460. | |

Johnson EK, Finlayson C. Preservation of Fertility Potential for Gender and Sex Diverse Individuals. Transgend Health 2016;1(1):41–4. doi:10.1089/trgh.2015.0010. | |

Rowell EE, Lautz TB, Lai K, et al. The ethics of offering fertility preservation to pediatric patients: A case-based discussion of barriers for clinicians to consider. Semin Pediatr Surg 2021;30(5):151095. doi:10.1016/j.sempedsurg.2021.151095. | |

Islam R, Lane S, Williams SA, et al. Establishing reproductive potential and advances in fertility preservation techniques for XY individuals with differences in sex development. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2019;91(2):237–44. doi:10.1111/cen.13994. | |

Finlayson C, Johnson EK, Chen D, et al. Fertility in Individuals with Differences in Sex Development: Provider Knowledge Assessment. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2022:S1083–3188(22)00179–6. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2022.02.004. | |

Alur-Gupta S, Vu M, Vitek W. Adolescent Fertility Preservation: Where Do We Stand Now. Semin Reprod Med 2021. doi:10.1055/s-0041-173589. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards programme CLICK HERE)