This chapter should be cited as follows:

Roos EJ, Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.418133

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Gynecology Module

Volume 2

Adolescent gynecology

Volume Editor: Professor Judith Simms-Cendan, University of Miami, USA

Chapter

Normal and Disordered Timing of Pubertal Development

First published: March 2023

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

INTRODUCTION

Puberty is a period of physical, psychological and social development for girls.1 Puberty is a process in which several maturational events come into play. The onset of puberty is determined by familial or genetic heritability, neuroendocrine factors, adequate nutritional status, energy expenditure in exercise and exposure to environmental chemicals.1 Changes in timing of puberty related to endocrine disrupters has been exposed in the media and is of concern both to providers and patients worldwide.

ORDER OF PUBERTAL DEVELOPMENT

In girls, the earliest manifestation of puberty is growth acceleration followed by pubarche, thelarche, accelerated growth velocity, and menarche. So, typically adrenarche occurs before gonadarche.2 The first sign of puberty appears between age 8 and 13 in 95% of the girls.3 Thelarche means the first appearance of breast development defined as Tanner stage B2.

The mean interval from Tanner stage B2 to menarche is 2.34 years with a standard deviation (SD) of 1.03 year.3,4 The interrelationships between these sexual maturation events vary between individuals. The correlation between breast development (B2) and menarche is rather low (0.17).

Several studies showed that girls can have different pathways to enter puberty. For the majority breast and pubic hair will develop simultaneously, and for others the entering of puberty can start with either thelarche or pubarche.2,5,6

In age at onset of puberty, a physiological variation is observed of 4–5 years. When a girl has entered puberty, the time from the first pubertal sign to complete all pubertal milestones varies from 1.5 years to over 6 years.3,6,7 For clinicians, it is more important to recognize the continued normal progression than the exact timing of pubertal milestones.3

Timing of pubertal onset: effects of global and demographic factors

In the last two decades, the onset of puberty appears to have transitioned to younger ages. Hypotheses explaining this shift encompass both intrinsic (nutritional status, epigenetic factors) and extrinsic factors, for instance inequalities related to socio-economic status or environment.

At the same time, an international trend towards earlier breast development is also noted.6 Several studies have linked increased childhood body mass index (BMI) and obesity to earlier breast development. The age at onset of breast development is varied by ethnicity and BMI. Data from the United States observed a median age at onset of breast stage 2 at 8.8, 9.3, 9.7 and 9.7 years in African American, Hispanic, white non-Hispanic, and Asian study participants whereas the mean ages for pubic hair development among girls were 9.5 years for non-Hispanic blacks, 10.3 years for Mexican-Americans, and 10.5 years for non-Hispanic whites.6,8

Whereas in the United States white American girls do have a mean age at menarche at 12.2 years,9 in countries like China the mean age at menarche in girls living in underprivileged conditions, is 16.1 years, while data from Nigeria showed an age at menarche of 13 years.7,10 A recent meta-analysis of pubertal milestones in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) showed that the estimate for the age at menarche is 12.3 years.11 Even within LMIC, regional differences are also observed in girls with a normal BMI, with a later age at menarche for girls living in the African region. The pooled estimate for Tanner stage 2 breast development in LMIC is 10.4 years.11,12 The onset of puberty in girls is highly sensitive to nutritional status and energy reserves, and this metabolic information is transmitted to gonadotropin-releasing-hormone (GnRH) neurons. So, while obesity during childhood may lead to premature thelarche or early pubertal onset, so is undernutrition globally one of the causes of delayed puberty and skeletal maturation. The plasma gonadotropin levels are lower in children with poor nutrition compared to age-matched controls with adequate nutrition, leading to the onset of puberty being delayed by an average of two years.11,13 On a global level, undernutrition, as a consequence delayed puberty, is still higher than the overnutrition causing obesity and early pubertal onset.

DEFINITIONS

Abnormal puberty is, according to the classical definition whether premature or delayed, with regard to the timing, 2.5 standard deviation (SD) below or above the mean of an ethnic population.

Adrenarche is a maturational increase in adrenal androgens, like dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS).

Pubarche is the clinical appearance of pubic hair.

Gonadarche is the earliest gonadal change referring to growth of ovaries in response to pituitary gonadotropins, that allows for the production of estradiol.

Thelarche is the development of breast tissue and is measured according to Tanner stage or so-called sexual maturation rating.

Menarche is the occurrence of the first menstruation.

Precocious puberty in girls is the appearance of secondary sex characteristics development before the age of 8 years in Caucasian girls and 6 years for African-American girls.

Premature thelarche is when unilateral or bilateral breast development without development of other sexual characteristics appears before 8 years of age.

Premature adrenarche is the presentation of androgenic symptoms like pubic or axillary hair, adult type body odor, oily hair or acne, before the age of 8 years.

Premature menarche is defined when girls below the age of 9 years have cyclic vaginal bleeding without other signs of pubertal development.

Delayed puberty is the absence of thelarche at the age of 13 years, or absence of menarche at 15 years in the presence of the secondary sex characteristics.

NORMAL PUBERTAL PROCESS

The factors that trigger the onset of puberty are elusive. Human genetic studies show that around 50–80% of the variation in pubertal onset is genetically determined. These genetic studies, in patients with central precocious puberty, have revealed more about genes involved and helped understand the neuroendocrine control of the onset of puberty.14,15,16,17,18,19

Genetics of puberty

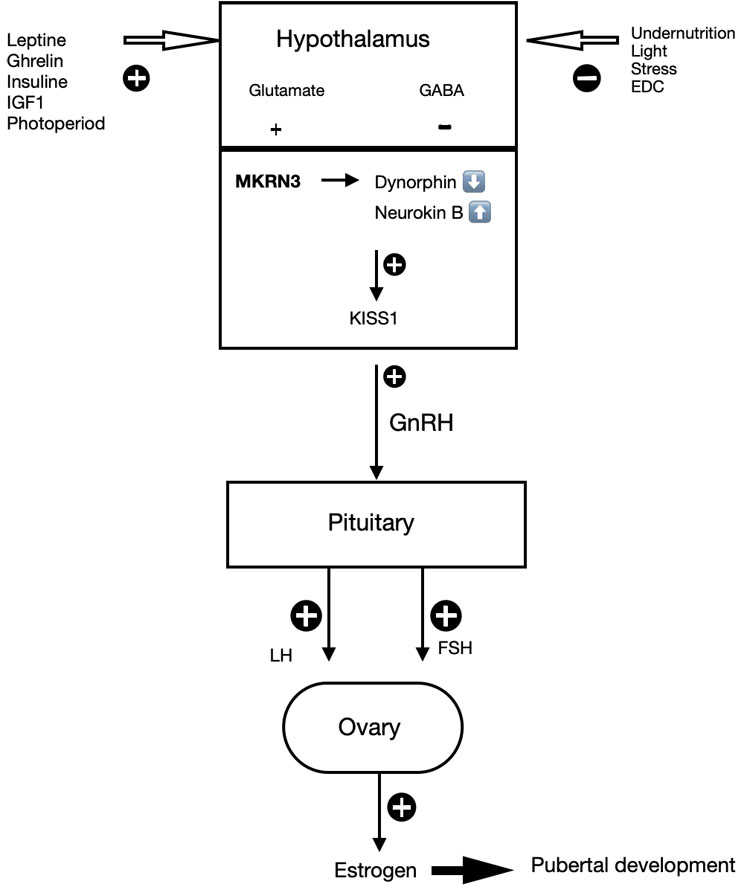

Puberty starts with the activation of the neuroendocrine network, resulting in the release of pulsatile GnRH secretion.15 Family and twin studies showed that 50% of the variation in age at menarche is due to genetic factors. From the genetic studies for central precocious puberty, the identification of loss-of-function mutations in the MKRN3 gene in association with the decrease in MKRN3 expression before the initiation of reproductive maturation, suggests that MKRN3 is acting as a brake on GnRH secretion during childhood.20,21,22 In more detail, the MRKN3 gene provides instructions for making a protein called the makorin ring finger protein 3 (MRKN3 protein). This MRKN3 protein blocks the release of GnRH from the hypothalamus.21,22 Based on the structure of the MRKN3 protein, it is thought to play a role in the cell and breaks down unwanted proteins by attaching a molecule ubiquitin to unwanted proteins. The breakdown of these proteins ensures that puberty does not start until the right time.20,21,22,23 The activity of the MRKN3 gene depends on which parent it was inherited from. Only the copy inherited from a girl's father is active and the copy from the mother is not active. This parent-specific difference in gene activation is called genomic imprinting.16,18,20,21,22

The MKRN3 expression is high in the hypothalamus of rats and nonhuman primates early in life, decreases as puberty approaches, and is independent of the production of sex steroid hormones. MKRN3 is expressed in Kiss1 neurons of the human hypothalamus and MKRN3 protein repressed promoter activity of human Kiss1 and TAC3, 2 key stimulators of GnRH secretion.20,21,22 MKRN3 mutations affecting the RING finger domain lead to less MRKN3 protein and ubiquitin production, so these mutations compromised the ability of MKRN3 to repress Kiss1 and TAC3 promoter activity.17,22 Genetic studies of families, with multiple members with disordered pubertal timing, led to identification of single gene mutations associated with hypogonadism and central precocious puberty.23,24 Genome-wide association studies have identified additional loci associated with the timing of puberty, timing of menarche, and BMI.22,24

Neurobiology of puberty

Mechanisms responsible for adrenarche function differently from awakening of the HPG axis. The molecular trigger for adrenarche remains also unclear. Environmental exposures such as stress and nutrition can influence the timing of adrenarche.8,25 The adrenal cortex consists of three distinct zones. The outer zone, the zona glomerulosa, synthesizes mineralocorticoids and is regulated by the renin – angiotensin pathway. The inner zone is most important for hormone production, and the third the zona reticularis secretes C19 steroids such as dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and dehydroepiandrosterone-sulphate (DHEAS).8 Androstenedione, DHEA, and DHEAS do not show significant androgen receptor agonist activity. Testosterone and dihydrotestosterone (DHT) are the most potent androgens, while 11-ketotestosterone and 11-keto-dihydrotestosterone are potent androgen receptor agonists. In peripheral tissues, 11-keto-testosterone can be converted to 11-ketodihydrote-tosterone by 5α-reductase type 2.8,25 Adrenarche starts with growth of pubic or axillary hair, and development of adult type body odor, oily hair or acne.8,25 Increased adrenal secretory activity makes more androgen precursors available for conversion to estrogen in peripheral tissues. Aromatase is the enzyme that catalyzes conversion of androgens into estrogens. With onset of adrenarche, DHEA and DHEAS concentrations rise with DHEAS concentrations peaking during the second decade of life.8,25

Puberty needs an intact hypothalamus-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis. The start of puberty is marked by the increased frequency and amplitude of gonadotropin-releasing-hormone (GnRH) secretion in the hypothalamus. This means that the increase in GnRH secretion starts when excitatory input increases, while inhibitory tone decreases.15 During childhood, Gamma amino butyric acid (GABA) is considered the major neurotransmitter that inhibits GnRH secretion. In addition, MKRN3 was proven to also have an inhibitory effect on GnRH release. The secretion of GnRH is regulated by kisspeptin (Kiss1) and its receptor Kiss-R1. Kiss1 is modulated by neurokinin B (stimulating effect increases Kiss1) and dynorphin (blocked inhibition), the so-called KNDy (kisspeptin, neurokinin and dynorphin) neurons.26 Kisspeptin is an important gatekeeper of the pubertal development.17,26 Other known influences on the timing of the onset of puberty includes the photoperiod, leptin levels, and glutamate, neuropeptide Y, endorphins, opioids, and melatonin. The fine tuning of these factors can modulate the pubertal process.

At puberty, the stimulatory effect of neurokinin b increases, while inhibition from dynorphin A is blocked. This results in an increase in GnRH secretion. The increased frequency and amplitude of GnRH secretion, involving an increase in excitatory input of kisspeptin through KNDy neurons and glutamate and a decrease in inhibitory inputs from GABA neurons. Glial cells play a facilitating role through growth factor production (e.g. TGFα, epithelial growth factor (EGF)).15,17 As a consequence, the increased GnRH stimulates the anterior pituitary to the secretion of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), which stimulates the ovary to produce estrogen.15 Estrogen stimulates the breast development, facilitate growth of uterus and ovaries, the vagina becomes longer, the vaginal mucosa thickens and is changing color (see Figure 1).

Several epidemiological studies indicate an earlier onset of puberty in girls who are overweight than girls of a healthy weight by several months.27,28 It has been assumed the central activation of GnRH neurons by leptin can be considered as a causal mechanism, however the relevant action of leptin, an adipose tissue hormone, as a stimulating factor on KNDy neurons has not been fully clarified.27 Leptin serves as a signal to the hypothalamic GnRH pulse generator that there are sufficient energy stores in the adipose tissue for fertility to commence, which is necessary but not sufficient for the initiation of puberty. Early pubertal signs might not solely be attributed to central onset of puberty, because adipose tissue has an aromatase action, which increases androgen conversion to estrogens.27 As a result, obesity might result in greater peripheral conversion of androstenedione to estrone, and testosterone to estradiol, independently of gonadotropins. The second assumption is that obesity influences pubertal development, so the relationship might be bidirectional as sex hormones increase bodyweight.27

Both androgens and estrogens affect skeletal maturation and bone health through their actions on osteoblasts, osteocytes, and osteoclasts. Obesity can further accelerate the rate of skeletal maturation in premature adrenarche; increased insulin, insulin-like growth factor 1, and leptin concentrations likely contribute to this acceleration.

Clinical monitoring

History taking is most important in establishing normal pubertal development.24 The history should be focused on the timing and sequence of pubertal milestones, transition between the pubertal stages, pubertal development of parents, chronic disease, associated features like anosmia, renal agenesis, or skeletal anomalies. Maternal age at menarche has been associated with all pubertal milestones with the exception of pubic hair development in girls.24 Physical examination should at least include height, weight in comparison to growth charts. The pubertal milestones are rated by Tanner stadia developed by Tanner and Marshall,3 also called sexual maturation rating (Table 1) and growth velocity is monitored in growth charts.

1

Sexual maturation rating by Tanner stadia and mean age of the stage, adapted from Marshall and Tanner.3

Tanner stage | Description | Mean age (years) |

Breast | ||

B1 | Elevation of the papilla only (pre-adolescent) | |

B2 | Breast bud stage | 11.15 |

B3 | Further enlargement of the breast and areola | 12.15 |

B4 | Areola and papilla form a mound above the breast | 13.11 |

B5 | Mature stage | 15.33 |

Pubic hair | ||

P1 | No pubic hair (pre-adolescent) | |

P2 | Sparse growth of long, slightly pigmented downy hair along the labia | 11.69 |

P3 | Darker, coarser, and more curled hair | 12.36 |

P4 | Adult type of hair and no spread to medial surface of the thighs | 12.95 |

P5 | Adult in quantity and type | 14.41 |

B, breast development; P, development of pubic hair.

TIMING DISORDERS

The diagnosis of abnormal puberty requires a good understanding of normal pubertal development and its temporal course, including the variations that affect 30–50% of girls.29,30 Timing disorders can be both early, precocious puberty, or late, delayed puberty. Both are determined by 2.5 standard deviations below or above the mean of the population. Depending on whether the process is normal, additional investigations, such as laboratory tests, X-ray of left hand to determine bone age, karyotyping or MRI (Table 2), can be carried out. Collaboration with a pediatric endocrinologist can be helpful in the diagnosis and management of pubertal disorders.

2

Investigations for timing disorders in puberty.

Test | Precocious puberty | Delayed puberty |

Growth rate | Accelerated growth31 | Normal to slower32 |

Tanner stage3 | Tanner stage B2 below 8 years of age31 | Defined as the absence of thelarche at the age of 13 years, or absence of menarche at 15 years in the presence of the secondary sex characteristics.26,32 |

Bone age | Advanced skeletal maturation compared to chronological31 | Bone age delay >2 years has been used as criterion for CDGP.32 |

Laboratory test | ||

| Look for other underlying illness as cause, e.g. diabetes mellitus.32 | |

| At least LH, FSH, estradiol, DHEA, DHEAS.31 | Should at least include LH, FSH, estradiol, IGF-1, prolactin, TSH and free T4.32 |

GnRH stimulation test | 100 mg of Leuprolide acetate is administered intravenous and gonadotropin levels are measured at baseline and at 60 minutes. A peak stimulated LH level of 4–6 mIU/l or an LH/FSH ratio >0.66 is considered pubertal.33 | GnRH testing is not helpful in the diagnosis of hypogonadotropic hypogonadism.34 |

Brain MRI | Considered in girls with CPP younger than 6 years, neurological symptoms or a predominant LH response in the GnRH stimulation test.35 | Imaging is performed when underlying disorders of the central nervous system are assumed.32 |

Pelvic ultrasound | Pelvic ultrasound can be of help, because increased uterine and ovarian dimensions have strong correlation with advanced bone age and are consistent with the diagnosis of CPP up to 8 years.36 | To establish if the uterus is absent or present.26 |

Karyogram | Patients with hypergonadotropic hypogonadism require karyotyping.26 |

Precocious puberty

Puberty is not precocious unless it occurs before 8 years for Caucasian girls and 6 years for African-American girls. There are three forms of precocious puberty:26,31

- central precocious puberty;

- peripheral precocious puberty;

- isolated benign variants.

In peripheral precocious puberty either the sequence or the pace of pubertal development is altered, while in central precocious puberty both the sequence and pace is preserved. The differential diagnosis of causes is listed in Table 3.

Central (GnRH dependent) | Peripheral (GnRH independent) | Incomplete form | |

Isosexual | Contrasexual | ||

Idiopathic (75%) | McCune Albright | CAH | Premature thelarche |

CNS-tumor (15–20%; e.g. optic glioma, hypothalamic astrocytoma, craniopharyngioma) | Granulosa cell tumor | Virilizing adrenal neoplasm (e.g. Cushing disease) | Premature adrenarche |

CNS disorders (5–10%; e.g. cerebral palsy, head trauma, cranial radiation, hydrocephalus, arachnoid cyst, infection) | Ovarian cyst | Aromatase deficiency | Premature menarche |

Genetic (e.g. MKRN3 mutations, Temple syndrome, Silver-Russell syndrome, DLK1 mutations) | Endocrine Disruptive Chemicals (e.g. pesticides) | Iatrogenic (e.g. exposure to androgens) | |

International adoption | Hypothyroidism | ||

Syndromes (e.g. Sturge-Weber syndrome, Neurofibromatosis type 1, | Iatrogenic (e.g. exposure to estrogens in food, drugs or cosmetics) | ||

Estrogen secreting adrenal tumor | |||

Peutz-Jager syndrome | |||

CNS, central nervous system; CAH, congenital adrenal hyperplasia

Central precocious puberty

Central precocious puberty (CPP) is caused by early maturation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis.37 The main causes of CPP are idiopathic, due to genetic mutations or are associated with central nervous system (CNS) abnormalities.26,31 A risk factor for CPP is congenital or acquired CNS disorders, about 20%. It is thought that CNS disorders such as spina bifida interfere with the ability to maintain a break on the hypothalamus. In approximately 75% of the girls CPP is idiopathic.

The known genetic underpinnings described in the scientific literature to date are mutations in coding for kisspeptin (Kiss 1) and the kisspeptin receptor (Kiss 1R) and in the MKRN3 gene.20,38

CPP usually presents with breast development with or without the growth of pubic hair next to growth acceleration and advanced skeletal maturation. The gold standard for diagnosis of CPP is a GnRH stimulation test. Usually, 100 mg of Leuprolide acetate is administered intravenous and gonadotropin levels are measured at baseline and at 60 min. A peak stimulated LH level of 4–6 mIU/l or an LH/FSH ratio >0.66 is considered pubertal.33

Pelvic ultrasound can be of help, because increased uterine and ovarian dimensions have strong correlation with advanced bone age and are consistent with the diagnosis of CPP up to 8 years.36 However, there is significant overlap of uterine and ovarian volumes between CPP and benign variants. Meta-analysis showed the benefit of routine brain MRIs in girls with CPP older than 6 years of age without any neurological concerns is not clear-cut, because intracranial pathology requiring intervention is a rare finding (1.6% having a brain tumor).35 Brain MRI should however be considered in girls with CPP younger than 6 years, neurological symptoms or a predominant LH response in the GnRH stimulation test.35

Goals of treatment include preservation of final adult height, prevention of social consequences of precocious puberty including challenges with hygiene in young menstruating girls, more risk for lower self-esteem and higher rate of depression, risks of sexual abuse, and earlier sexual debut.4,26,39 It should be noted that girls who have precocious puberty are not more promiscuous, it is the premature development of secondary sex characteristics that triggers unwanted sexual advances by others. These vulnerable girls are often not equipped to handle the external social pressures,31,39 and they and their families should be provided extra support.

The dilemma to start treatment depends on age, time of sexual maturation and predicted adult height. GnRH analogs (GnRHas) continuously stimulate the pituitary gonadotrophs, which leads to suppression of gonadotropin release, and results in decreased sex steroid production. Leuprolide acetate is a long-acting GnRHa, which can be used in the form of monthly intramuscular injection, but also in a 3-monthly depot.40 Research has shown that monthly dosing of leuprolide achieves better biochemical suppression than a 3-monthly depot formulation.41 The GnRHa treatment should be monitored by evaluating pubertal progression with growth velocity and annually bone age X-rays. The monitoring of LH and sex steroids is controversial, but can be helpful if pubertal progression continues during treatment to assess whether complete suppression of the HPG axis has been realized.37 The common side effects might be headaches, hot flushes, and local skin reaction at the site of the depot injection. Vaginal bleeding might occur the first weeks following the initial dose of GnRHa due to estrogen withdrawal. No negative effect of GnRHa treatment in girls with CPP has been found on BMI or permanent reduction of bone mineral density. While it is known that premature adrenarche increases risk of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), there is conflicting evidence on whether CPP itself or the treatment with GnRHa for CPP leads to a risk of development of PCOS.42

Peripheral precocious puberty

Peripheral precocious puberty (PPP) is GnRH independent. This means that in PPP, early puberty is caused by an excess of steroid hormones independent of activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis (HPO). It may be due to exogenous exposure or increased endogenous production or hormones from the ovaries or adrenal glands. If PPP is left untreated it can progress to central precious puberty.31 PPP can be subdivided into isosexual when the sexual characteristics are according to the girl's gender (feminizing, due to estrogens) and contrasexual when the changes are masculinizing (due to androgens).

The clinical expression of PPP has a wide range. In approximately 50–60% of PPP causes is premature development of one sexual characteristic (see 1.3 isolated variants of timing disorders), 10–20% is actually central precocious puberty and in 10% PPP is caused by an adrenal or ovarian cause.26,31 In taking the patient history, it is important to ask for exposure of exogenous hormones that can be in over-the-counter medications or homeopathic therapies. Physical examination focuses on height, weight, Tanner staging, and bone age. Additional laboratory investigation: LH, FSH, estradiol, testosterone, DHEAS, and GnRH stimulation test.

McCune Albright Syndrome (MAS) is a triad of precocious puberty, café-au-lait skin macules with irregular borders and fibrous dysplasia of the bone. MAS is a mosaic disease and not inherited.31,43 MAS appears in all ethnic groups. In 85% of the girls the GNAS activation in ovarian tissue leads to recurrent estrogen-producing cysts. Patients show acute onset of pubertal signs due to elevated estradiol levels with suppressed gonadotropins and no response of gonadotropins to GnRH stimulation.31 Pelvic ultrasound commonly shows uterine enlargement with single or multiple ovarian cysts. The resolution of the ovarian cyst leads to a drop in estradiol, which in its turn leads to withdrawal vaginal bleeding. The diagnosis of MAS is made clinically based on two or more characteristic features.43 Between episodes, girls are often clinically asymptomatic with undetectable estradiol levels. An uncommon complication can be ovarian torsion due to the ovarian cysts.43 Girls with MAS are managed with the aromatase inhibitor letrozole, which decreases the frequency of vaginal bleeding and improves the final adult height. If letrozole monotherapy is ineffective, estrogen receptor modulators such as tamoxifen and fulvestrant may be considered.43

Granulosa cell tumors (GCT) is another cause of PPP.31,44 Less than 5% of the GCT occur before puberty.44 The GCT have a strong estrogen secretion, leading to PPP in 70–90%, and increase in inhibin B and anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH). The triad of a palpable adnexal mass, elevated serum estradiol levels, and absent or decreased gonadotropins (FSH and LH) have been reported to be almost diagnostic of a GCT in a girl before menarche.44 Surgery with possible fertility preservation is the appropriate treatment. Due to its excellent prognosis and often the complete recovery after initial surgery, juvenile OGCT has usually been considered as a benign condition. Survival of the patients with stage IA tumors is around 90%, the overall survival in the whole group approximating 85%.31,44 Both exposure to exogenous hormones and endocrine disrupters can also cause PPP.

Isolated variants of timing disorders

Isolated premature adrenarche

Usually, around 5–8 years of age, a maturational increase in adrenal androgens, like dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS), develops and is called adrenarche. Premature adrenarche is the presentation of androgenic symptoms like pubic or axillary hair, adult type body odor, oily hair of acne, before the age of 8 years.8,45,46,47,48,49 Approximately 1% of the girls have premature adrenarche with an average age of onset between 3–8 years.

The clinical presentation of premature adrenarche manifests in a typical order, although the circulating androgen levels vary.47 Commonly, the first clinical sign is adult-type body odor, while axillary and pubic hair are typically the last androgenic signs.46,47

DHEAS is seen as the best marker for androgen secretion. The other androgens like DHEA and androstenedione can also be increased for age. In contrast, it is not abnormal for girls with signs of premature adrenarche to have normal prepubertal DHEAS concentration <1 mmol/l (approximately equal to 40 mg/dl).25,46,47,48 Premature adrenarche may be accompanied by overweight and increased prepubertal height. Many times, the bone age is advanced and appropriate for the increase in height. Observation from longitudinal cohorts shows that menarche occurs 0.5–1 years earlier than appropriate for the ethnic population and towards earlier thelarche.47,49 Potential hypothesis might be that the increased androgen exposure leads to increased peripheral conversion of androgens into estrogens without gonadotropin activation.49

Premature adrenarche is a diagnosis per exclusion after ruling out CPP, androgen secreting adrenal or gonadal tumor (rare in children), nonclassical congenital hyperplasia (NCAH), Cushing disease and iatrogenic causes, such as exposure to exogenous androgens in creams. The difference between CPP and premature adrenarche is the finding of Tanner stage >B2 in girls with CPP. Of this differential diagnosis the late onset NCAH is most common and due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency. The prevalence of NCAH amongst girls with premature adrenarche varies in different study populations and varies between 0–43%. To differentiate between NCAH from premature adrenarche, 17 hydroxy progesterone (17-OH-progesterone) or ACTH stimulation test is needed.8

Follow-up of girls every 6–18 months is indicated to monitor height, weight, androgenic symptoms and pubertal development.8,47 In overweight girls the advice is to encourage to lifestyle modification, such as healthy diet and physical exercise. They should be monitored with blood glucose, insulin level, or oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT or HbA1C) as girls with premature adrenarche are at increased risk for developing obesity-related metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance.

Specific treatment is not required in premature adrenarche.25,47,48 Girls with premature adrenarche are at risk for developing adrenal and ovarian hyperandrogenism. The relationship of premature adrenarche to PCOS remains unsolved, because not all girls with premature adrenarche develop PCOS and not all girls with PCOS had premature adrenarche.8,50

Isolated premature thelarche

When unilateral or bilateral breast development without development of other sexual characteristics appears before 8 years of age, it is called premature thelarche.26,45,51,52 The prevalence in girls <48 months is 2.2–4.7%.51 In about 80% of the girls with premature thelarche, it appears before the age of 2 years.26,52 Usually it does not progress beyond Tanner stage 3 and in unilateral cases beyond Tanner stage 2. Commonly, premature thelarche is self-limiting.51

Several hypotheses exist about the cause of premature thelarche. This can be either increased breast tissue sensitivity to estrogen, increased estrogen production or intake (either dietary or transdermal like lavender and tea tree oil)53 or transient partial activation of the HPO axis.

There are four patterns described in the course of premature thelarche.51,52 A cohort of 139 girls with premature thelarche were followed over the course of 6.5 years. Spontaneous regression occurred in 50% of the cases, persisted in 36%, cyclic pattern in 9%, and only 3% progressed to central precocious puberty. The mean time for regression was 16 months with a range of 3–43 months.52

Although most cases spontaneously regress, it remains important to differentiate between premature thelarche and precocious puberty. Follow up every 3–6 months can be sufficient.51 There are some laboratory (basal gonadotropins and estradiol) and imaging studies (bone age assessment and pelvic ultrasound) can be helpful, but none of the tests can predict which girls are at risk of developing central precocious puberty. Bone age in premature thelarche girls is consistent with their chronological age. In girls with isolated premature thelarche, a prepubertal uterine and ovarian volume is usually seen. Sometimes functional ovarian cysts can be seen as the source of estrogen. The mean FSH level is not different between girls with premature thelarche or CPP. A single LH value may not be sufficient to differentiate between CPP and premature thelarche, because there is an overlap in the expected values.51

Isolated premature menarche

When girls below the age of 9 years have cyclic vaginal bleeding without other signs of pubertal development, the diagnosis is called isolated premature menarche.26,45 Premature menarche is a diagnosis of exclusion. Other causes of vaginal bleeding need to be ruled out, like infection, trauma, tumor of the genital tract, foreign bodies, sexual abuse, or central precocious puberty.45

Premature menarche is a rare condition and can occur once or be recurring. The onset may be increased in the winter months.54 Usually, premature menarche resolves after 1–2 years. The girls will have normal onset of puberty.45 These girls do not have an acceleration in growth nor advanced skeletal maturation.54 In a follow-up study of girls with premature menarche, pelvic ultrasound showed prepubertal uterine volume.54 Premature menarche is not well understood, but it seems to be due to hypersensitivity of the endometrium to low levels of estrogens.26

Delayed puberty

Delayed puberty occurs in about 2% of girls, and is defined as is the absence of thelarche at the age of 13 years, or absence of menarche at 15 years in the presence of the secondary sex characteristics. A family history of delayed puberty is present in up to 50% of parents or siblings.26,32,55,56,57 Late puberty, either congenital or acquired, is classified into three major groups, see Table 4:

- Constitutional delay in growth and puberty (CDGP);

- Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, due to immaturity or failure of GnRH production;

- Hypergonadotropic gonadism due to gonadal failure or failure of gonadal sex steroid production.

4

Causes, prevalence and hormonal profile in delayed puberty. Adapted from Sultan, Klein and Raivio.26,58,34

Causes | Prevalence | Gonadotropins | Sex hormones |

Constitutional delay in growth and puberty | 30% | ↓LH, ↓FSH, but are in line for bone age | ↓E2, but are in line for bone age |

Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism | ↓LH, ↓FSH | ↓E2 | |

| 20% | ||

| 15–20% | ||

Hypergonadotropic hypogonadism | ↑LH, ↑FSH | ↓E2 | |

| 13% | ||

| |||

Idiopathic | 5% | ↓LH, ↓FSH | ↓E2 |

LH, luteinizing hormone; FSH, follicle stimulating hormone; E2, estradiol.

Constitutional delay in puberty is responsible for 30% of the cases of delayed puberty.26,57 In about half of the girls, one of the parents also had delayed puberty. In laboratory the gonadotropins and estrogen are within the normal range for age and Tanner stage. CDGP is a diagnosis of exclusion. CDGP is a self-limiting condition, in which there is normal pubertal development, only occurring later.58 When puberty begins but then normal progression of milestones stops, for example thelarche occurs but menarche has not started more than 2 years later, the full differential diagnosis of primary amenorrhea, including disorders of Mullerian development and disorders of sex development (DSD) as complete androgen insensitivity should be considered.59

Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism can be functional due to systemic illness like cystic fibrosis, diabetes mellitus, chronic pain, or undernutrition. Other causes are genetic like in Kallman syndrome, where a defect in the KAL-1 gene causes delayed puberty, hyposmia or anosmia, and can be accompanied by renal or midline facial defects.56 Patients with CHARGE, Prader-Willi, and Gordon Holmes syndrome may also be associated with central hypogonadism.56 In laboratory testing, patients are found to have a low LH, low FSH, and low estrogen.26,56,57

Hypergonadotropic hypogonadism can be caused by congenital chromosome abnormalities like Turner syndrome, or be acquired by autoimmune ovarian failure or be due to the gonadotoxic effects of pelvic radiation or cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agents. Girls with Turner syndrome have pubarche and 15–30% will have breast development, prior to cessation of ovarian function.26,57 In laboratory testing, affected girls have high LH, high FSH and low estrogen.

In delayed puberty, it is important in history taking to make a distinction between an arrest of pubertal development versus delayed initiation of puberty. It is important to note the presence of chronic disease, medication use, abnormal sense of smell, headaches, visual disturbance, seizures, chemotherapy, nutrition (anorexia), the amount of exercise and parental pubertal development.58 The diagnosis of delayed puberty is made by physical examination and laboratory evaluation. Physical examination entails longitudinal growth and weight, sexual characteristics by Tanner stadia, an X-ray of the left hand (bone age).26,58 Laboratory evaluation should include an LH, FSH, estradiol, TSH and free T4. Patients with hypergonadotropic hypogonadism require a karyotype to rule out Turner syndrome or a Turner Mosaic.26 A pelvic ultrasound is important to establish if the uterus is absent or present.26 GnRH testing is not helpful in the diagnosis of hypogonadotropic hypogonadism.34 Currently there is no diagnostic test that can differentiate between all forms of CDGP and CHH.34,60,61

For girls with constitutional delay of puberty, reassurance and watchful waiting is appropriate. A follow-up appointment after 6 months is recommended to ensure that pubertal development has progressed. When during follow-up no activation of the HPG axis is observed, second line investigation for the etiology of delayed puberty should be done.58 GnRH is not recommended for treatment of CDGP.32

The goal of the treatment of girls with hypo- or hypergonadotropic hypogonadism is to ensure full pubertal development of secondary sexual characteristics and uterine growth and ensure normal growth velocity and bone mass acquisition.34,62,63 In cases of hypergonadotropic hypogonadism with high gonadotropin levels, it is important to consider estrogen treatment beginning at 11–12 years of age. From data in women with Turner syndrome, it is known that delay of estrogen therapy until 15 years of age leads to lower bone density,63 however scientific data regarding the optimal age range for starting estrogen therapy is lacking.34 Estrogen replacement therapy starts at low doses and should be gradually increased by a 6-month interval to preserve growth potential.34 When puberty is induced with estrogen, it takes approximately 3 years to reach adult dosage of estrogen.58 Puberty induction with estrogen replacement therapy has no consensus regarding the type of estrogen,34,63,64 treatment route, dose and dosing time, or tempo. In theory, transdermal approach might be beneficial because the more physiological route of delivery, avoiding the first pass effect, and decreased risk of stroke, however, scientific data are lacking.34,62,63 Please be aware that availability and trade names of estradiol differ among countries. In girls who have a uterus, progesterone is added after 2 years on adult dosage (20–25 μg/day) or when breakthrough bleeding occurs to prevent endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer in unopposed estrogen.34,55,62,63

CONCLUSION

Puberty is a sequential maturation process. The activation of the neuroendocrine network starts with decreased MKRN3 expression, leading to an increase in KISS1 resulting in the release of pulsatile GnRH, and increase in LH, FSH and estrogen. The increased estrogen production leads to thelarche, commonly seen between 8 and 13 years. The final pubertal milestone is menarche. This chapter deals with precocious puberty and delayed puberty.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- The onset of puberty is determined by familial or genetic heritability, neuroendocrine factors, nutritional status, exercise and environmental chemicals.

- In 95% of girls, the first sign of puberty appears between the ages of 8 and 13 years, typically presenting as thelarche, which corresponds to Tanner stage 2 breast development. The average time from Tanner stage B2 to menarche is approximately 2.34 years, with a standard deviation of 1.03 years.

- Puberty needs an intact hypothalamus-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis.

- The start of puberty is marked by the increased frequency and amplitude of gonadotropin-releasing-hormone (GnRH) secretion in the hypothalamus. The secretion of GnRH is regulated by kisspeptin and its receptor KISS-R1, and is modulated by neurokinin B and dynorphin, the KNDy neurons.

- MKRN3 acts as a brake on GnRH secretion during childhood and decreases as puberty approaches, independent of sex-steroid hormone production. MKRN3 is expressed in KISS1 and TAC3 neurons of the hypothalamus, the two key stimulators of GnRH secretion.

- Increased GnRH secretion stimulates the anterior pituitary to secrete luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), which stimulate the ovary to produce estrogen.

- Mechanisms responsible for adrenarche function differently from the HPG axis. The molecular trigger for adrenarche remains unclear.

- With onset of adrenarche, DHEA and DHEAS concentrations rise, with DHEAS concentrations peaking during the second decade of life.

- Central precocious puberty (CPP) is caused by early maturation of the HPG axis. The main causes of CPP are idiopathic, due to genetic mutations, or association with central nervous system abnormalities.

- CPP is idiopathic in approximately 75% of the girls.

- The gold standard for diagnosis of CPP is a GnRH stimulation test. Usually, 100 mg of leuprolide acetate is administered intravenously and gonadotropin levels are measured at baseline and at 60 min. A peak stimulated LH level of 4–6 mIU/l or an LH/FSH ratio >0.66 is considered pubertal.

- GnRH analogs (GnRHas) stimulate the pituitary gonadotrophs, which leads to suppression of gonadotropin release, and results in decreased sex steroid production. Monthly GnRHas dosing achieves better biochemical suppression compared to a 3-monthly depot.

- Peripheral precocious puberty (PPP) is GnRH independent, meaning that early puberty is caused by an excess of steroid hormones independent of activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis. It is predominantly caused by estrogens and rarely by androgens.

- In PPP either the sequence or the pace of pubertal development is interrupted, while, in CPP, both the sequence and pace are normal.

- The history of a girl with delayed puberty provides clues for the underlying etiology.

- Constitutional delay in growth and puberty is the most common cause of delayed puberty and it is inherited in approximately 50% of cases.

- Differential diagnosis between constitutional delay and congenital hypogonadotropic hypogonadism can be difficult and there is no diagnostic test that can differentiate between them.

- In puberty induction with estrogen replacement therapy, there is no consensus regarding the type of estrogen, treatment route, dose and dosing time or tempo.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) of this chapter declare that they have no interests that conflict with the contents of the chapter. She has no financial disclosures.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

REFERENCES

Dietrich JE (ed.) Female Puberty: A comprehensive guide for clinicians. DOI 10.1007/978-1-4939-0912-4_1. Springer Science +Business Media New York, 2014. | |

Biro FM, Huang B, Daniels SR, et al. Pubarche as well as thelarche may be a marker for the onset of puberty. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2008;21(6):323–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2007.09.008. PMID: 19064225; PMCID: PMC3576862. | |

Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Arch Dis Child 1969;44(235):291–303. doi:10.1136/adc.44.235.291 PMID: 5785179; PMCID: PMC2020314. | |

Cheng HL, Harris SR, Sritharan M, et al. The tempo of puberty and its relationship to adolescent health and well‐being: A systematic review. Acta Paediatrica 2020;109(5):900–13. doi.org/10.1111/apa.15092. | |

Fassler CS, Gutmark-Little I, Xie C, et al. Sex Hormone Phenotypes in Young Girls and the Age at Pubertal Milestones. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2019;104(12):6079–89. doi: 10.1210/jc.2019-00889. PMID: 31408174; PMCID: PMC6821200. | |

Biro FM, Greenspan LC, Galvez MP, et al. Onset of breast development in a longitudinal cohort. Pediatrics 2013;132(6):1019–27. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-3773. PMID: 24190685; PMCID: PMC3838525. | |

Parent AS, Teilmann G, Juul A, et al. The timing of normal puberty and the age limits of sexual precocity: variations around the world, secular trends, and changes after migration. Endocr Rev 2003;24(5):668–93. doi: 10.1210/er.2002-0019. PMID: 14570750. | |

Witchel SF, Pinto B, Burghard AC, et al. Update on adrenarche. Curr Opin Pediatr 2020;32(4):574–81. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000928. PMID: 32692055; PMCID: PMC7891873. | |

Biro FM, Pajak A, Wolff MS, et al. Age of Menarche in a Longitudinal US Cohort. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2018;31(4):339–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2018.05.002. PMID: 29758276; PMCID: PMC6121217. | |

Eyong ME, Ntia HU, Ikobah JM, et al. Pattern of pubertal changes in Calabar, South South Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J 2018;31:20. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2018.31.20.15544. PMID: 30923594; PMCID: PMC6431415. | |

Moodie JL, Campisi SC, Salena K, et al. Timing of Pubertal Milestones in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Adv Nutr 2020;11(4):951–9. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmaa007. PMID: 32027344; PMCID: PMC7360440. | |

Eckert-Lind C, Busch AS, Petersen JH, et al. Worldwide Secular Trends in Age at Pubertal Onset Assessed by Breast Development Among Girls: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr 2020;174(4):e195881. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.5881. | |

German A, Shmoish M, Belsky J, et al. Outcomes of pubertal development in girls as a function of pubertal onset age. Eur J Endocrinol 2018;179(5):279–85. doi: 10.1530/EJE-17-1025. PMID: 30087116. | |

Spaziani M, Tarantino C, Tahani N, et al. Hypothalamo-Pituitary axis and puberty. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2021;520:111094. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2020.111094. PMID: 33271219. | |

Hughes IA. Releasing the brake on puberty. N Engl J Med 2013;368(26):2 513–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1306743. PMID: 23738512. | |

Abreu AP, Dauber A, Macedo DB, et al. Central precocious puberty caused by mutations in the imprinted gene MKRN3. N Engl J Med 2013;368(26):2467–75. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1302160. PMID: 23738509; PMCID: PMC3808195. | |

Plant TM. Neuroendocrine control of the onset of puberty. Front Neuroendocrinol 2015;38:73–88. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2015.04.002. PMID: 25913220; PMCID: PMC4457677. | |

Hagen CP, Sørensen K, Mieritz MG, et al. irculating MKRN3 levels decline prior to pubertal onset and through puberty: a longitudinal study of healthy girls. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015;100(5):1920–6. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-4462. PMID: 25695892. | |

Witchel SF, Plant TM. Neurobiology of puberty and its disorders. Handb Clin Neurol 2021;181:463–96. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-820683-6.00033-6. PMID: 34238478. | |

Abreu AP, Macedo DB, Brito VN, et al. A new pathway in the control of the initiation of puberty: the MKRN3 gene. J Mol Endocrinol 2015;54(3):R131–9. doi: 10.1530/JME-14-0315. PMID: 25957321; PMCID: PMC4573396. | |

Abreu AP, Toro CA, Song YB, et al. MKRN3 inhibits the reproductive axis through actions in kisspeptin-expressing neurons. J Clin Invest 2020;130(8):4486–500. doi: 10.1172/JCI136564. PMID: 32407292; PMCID: PMC7410046. | |

Day FR, Perry JR, Ong KK. Genetic Regulation of Puberty Timing in Humans. Neuroendocrinology 2015;102(4):247–55. doi: 10.1159/000431023. PMID: 25968239; PMCID: PMC6309186. | |

Dvornyk V, Waqar-ul-Haq. Genetics of age at menarche: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update 2012;18(2):198–210. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmr050. PMID: 22258758. | |

Witchel SF. Disorders of Puberty: Take a Good History! J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2016;101(7):2643–6. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-2116. PMID: 27381960. | |

Rosenfield RL. Normal and Premature Adrenarche. Endocr Rev 2021;42(6):783–814. doi: 10.1210/endrev/bnab009. PMID: 33788946; PMCID: PMC8599200. | |

Sultan C, Gaspari L, Maimoun L, et al. Disorders of puberty. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2018;48:62–89. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2017.11.004. PMID: 29422239. | |

Reinehr T, Roth CL. Is there a causal relationship between obesity and puberty? Lancet Child Adolesc 2019;3(1):44–54. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30306-7. PMID: 30446301. | |

Smith CE, Biro FM. Pubertal Development: What's Normal/What's Not. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2020;63(3):491–503. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000537. PMID: 32482957. | |

Khan L. Puberty: Onset and Progression. Pediatr Ann 2019;48(4):e141–5. doi: 10.3928/19382359-20190322-01. PMID: 30986314. | |

Wei C, Davis N, Honour J, et al. The investigation of children and adolescents with abnormalities of pubertal timing. Ann Clin Biochem 2017;54(1):20–32. doi: 10.1177/0004563216668378. PMID: 27555666. | |

Sultan C, Gaspari L, Kalfa N, et al. Clinical expression of precocious puberty in girls. Endocr Dev. 2012;22:84–100. doi: 10.1159/000334304. PMID: 22846523. | |

Palmert MR, Dunkel L. Clinical practice. Delayed puberty. N Engl J Med 2012;366(5):443–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1109290. PMID: 22296078. | |

Carretto F, Salinas-Vert I, Granada-Yvern ML, et al. The usefulness of the leuprolide stimulation test as a diagnostic method of idiopathic central precocious puberty in girls. Horm Metab Res 2014;46(13):959–63. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1387790. PMID: 25295414. | |

Klein KO, Phillips SA. Review of Hormone Replacement Therapy in Girls and Adolescents with Hypogonadism. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2019;32(5):460–8. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2019.04.010. PMID: 31059821. | |

Cantas-Orsdemir S, Garb JL, Allen HF. Prevalence of cranial MRI findings in girls with central precocious puberty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2018;31(7):701–10. doi: 10.1515/jpem-2018-0052. PMID: 29902155. | |

de Vries L, Horev G, Schwartz M, et al. Ultrasonographic and clinical parameters for early differentiation between precocious puberty and premature thelarche. Eur J Endocrinol 2006;154(6):891–8. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.02151. PMID: 16728550. | |

Cantas-Orsdemir S, Eugster EA. Update on central precocious puberty: from etiologies to outcomes. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab 2019;14(2):123–30. doi: 10.1080/17446651.2019.1575726. PMID: 30763521. | |

Bulcao Macedo D, Nahime Brito V, Latronico AC. New causes of central precocious puberty: the role of genetic factors 2014;100(1):1–8. doi: 10.1159/000366282. PMID: 25116033. | |

Galvao TF, Silva MT, Zimmermann IR, et al. Pubertal timing in girls and depression: a systematic review. J Affect Disord 2014;155:13–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.10.034. PMID: 24274962. | |

Carel JC, Eugster EA, Rogol A, et al. Consensus statement on the use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs in children. Pediatrics 2009;123(4):e752–62. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1783. PMID: 19332438. | |

Durand A, Tauber M, Patel B, et al. Meta-Analysis of Paediatric Patients with Central Precocious Puberty Treated with Intramuscular Triptorelin 11.25 mg 3-Month Prolonged-Release Formulation. Horm Res Paediatr 2017;87(4):224–32. doi: 10.1159/000456545. PMID: 28334719. | |

Lazar L, Meyerovitch J, de Vries L, et al. Treated and untreated women with idiopathic precocious puberty: long-term follow-up and reproductive outcome between the third and fifth decades. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2014;80(4):570–6. doi: 10.1111/cen.12319. PMID: 24033561. | |

Spencer T, Pan KS, Collins MT, et al. The Clinical Spectrum of McCune-Albright Syndrome and Its Management. Horm Res Paediatr 2019;92:347–56. doi: 10.1159/000504802. | |

Fleming NA, de Nanassy J, Lawrence S, et al. Juvenile granulosa and theca cell tumor of the ovary as a rare cause of precocious puberty: case report and review of literature. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2010;23(4):e127–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2010.01.003. PMID: 20371195. | |

Farello G, Altieri C, Cutini M, et al. Review of the Literature on Current Changes in the Timing of Pubertal Development and the Incomplete Forms of Early Puberty. Front Pediatr 2019;7:147. doi: 10.3389/fped.2019.00147. PMID: 31139600; PMCID: PMC6519308. | |

Appiah LA. Isolated precocious puberty. In: Dietrich JE. Female Puberty: a comprehensive guide for clinicians. New York: Springer Science + business media; 2014;89–95. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-0912-4_8. | |

Utriainen P, Laakso S, Liimatta J, et al. Premature adrenarche-a common condition with variable presentation. Horm Res Paediatr 2015;83(4):221–31. doi: 10.1159/000369458. Epub 2015 Feb 7. PMID: 25676474. | |

Oberfield SE, Tao RH, Witchel SF. Present Knowledge on the Etiology and Treatment of Adrenarche. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev 2018;15(3):244–54. doi: 10.17458/per.vol15.2018.otw.etiologytreatmentadrenarche. PMID: 29493129. | |

Liimatta J, Utriainen P, Voutilainen R, et al. Girls with a History of Premature Adrenarche Have Advanced Growth and Pubertal Development at the Age of 12 Years. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2017;8:291. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2017.00291. PMID: 29163361; PMCID: PMC5671637. | |

Livadas S, Bothou C, Kanaka-Gantenbein C, et al. Unfavorable Hormonal and Psychologic Profile in Adult Women with a History of Premature Adrenarche and Pubarche, Compared to Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Horm Metab Res 2020;52(3):179–85. doi: 10.1055/a-1109-2630. PMID: 32074632. | |

Khokhar A, Mojica A. Premature Thelarche. Pediatr Ann 2018;47(1):e12–5. doi: 10.3928/19382359-20171214-01. PMID: 29323691. | |

de Vries L, Guz-Mark A, Lazar L, et al. Premature thelarche: age at presentation affects clinical course but not clinical characteristics or risk to progress to precocious puberty. J Pediatr 2010;156(3):466–71. doi:10.1016/j. jpeds.2009.09.071. | |

Hawkins J, Hires C, Dunne E, et al. The relationship between lavender and tea tree essential oils and pediatric endocrine disorders: A systematic review of the literature. Complement Ther Med 2020;49:102288. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2019.102288. PMID: 32147050. | |

Ejaz S, Lane A, Wilson T. Outcome of Isolated Premature Menarche: A Retrospective and Follow-Up Study. Hormone Research in Paediatrics 2015;84(4):217–22. doi:10.1159/000435882. | |

Trotman GE. Delayed puberty in the female patient. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2016;28(5):366–72. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000303. PMID: 27454850. | |

Howard SR, Dunkel L. Delayed Puberty-Phenotypic Diversity, Molecular Genetic Mechanisms, and Recent Discoveries. Endocr Rev 2019;40(5):1285–317. doi: 10.1210/er.2018-00248. Erratum in: Endocr Rev 2020;41(1). PMID: 31220230; PMCID: PMC6736054. | |

Dye AM, Nelson GB, Diaz-Thomas A. Delayed Puberty. Pediatr Ann 2018;47(1):e16–22. doi: 10.3928/19382359-20171215-01. PMID: 29323692. | |

Raivio T, Miettinen PJ. Constitutional delay of puberty versus congenital hypogonadotropic hypogonadism: Genetics, management and updates. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2019;33(3):101316. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2019.101316. PMID: 31522908. | |

Lanciotti L, Cofini M, Leonardi A, et al. Different Clinical Presentations and Management in Complete Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome (CAIS). Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16(7):1268. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16071268. PMID: 30970592; PMCID: PMC6480640. | |

Bollino A, Cangiano B, Goggi G, et al. Pubertal delay: the challenge of a timely differential diagnosis between congenital hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and constitutional delay of growth and puberty. Minerva Pediatr 2020;72(4):278–87. doi: 10.23736/S0026-4946.20.05860-0. PMID: 32418410. | |

Galazzi E, Persani LG. Differential diagnosis between constitutional delay of growth and puberty, idiopathic growth hormone deficiency and congenital hypogonadotropic hypogonadism: a clinical challenge for the pediatric endocrinologist. Minerva Endocrinol 2020;45(4):354–75. doi: 10.23736/S0391-1977.20.03228-9. PMID: 32720501. | |

RCOG scientific impact paper, no. 40. Sex steroid treatment for pubertal induction and replacement in the adolescent girl. June 2013. Retrieved from www.rcog.uk/guidelines. Accessed 28 November 2021. S. | |

Klein KO, Rosenfield RL, Santen RJ, et al. Estrogen Replacement in Turner Syndrome: Literature Review and Practical Considerations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2018;103(5):1790–803. doi: 10.1210/jc.2017-02183. PMID: 29438552. | |

Zacharin M. Pubertal induction in hypogonadism: Current approaches including use of gonadotrophins. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015;29(3):367–83. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2015.01.002. PMID: 26051297.eroid Treatment for Pubertal Induction. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards programme CLICK HERE)