This chapter should be cited as follows:

Dumont T, Torres A, Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.418063

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Gynecology Module

Volume 2

Adolescent gynecology

Volume Editor: Professor Judith Simms-Cendan, University of Miami, USA

Chapter

Simulation Training in Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology

First published: November 2022

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

BASIS OF SIMULATION-BASED EDUCATION (SBE)

Healthcare simulation plays a critical role in patient safety; therefore it is important to integrate simulation at all levels of education. In Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology (PAG), prior training in a simulated environment is of special importance, as the encounter with gynecologist is a very stressful experience for most PAG patients and their caregivers.

There are multiple definitions of simulation; however, in this chapter we use the definition from Professor David Gaba, a pioneer in healthcare simulation: Simulation is a technique – not a technology – to replace or amplify real experiences with guided experiences that evoke or replicate substantial aspects of the real world in a fully interactive manner.1

It is important to acknowledge that the role of simulation in PAG education is broader than technical skill acquisition. Many adverse incidents in medical practice arise from failure in non-technical domains such as communication, teamwork, or situational awareness rather than technical expertise.2,3 Simulation can be employed to promote learning, practice, and assessment of both technical and non-technical skills in a patient-safe environment. It also allows for specific rehearsal of rare or unique situations.4

Similar to other educational strategies, simulation is informed by coherent frameworks of ideas called learning theories. Learning theory can guide the general approach to simulation, the way it is implemented into the curriculum, simulation scenario design, development, and facilitation. It can also inform the approach to feedback and debriefing. In many instances, simulation is guided by more than one learning theory, and different aspects of simulation implementation may benefit from aspects rooted in various learning theories.

It is important for the clinical teachers to be aware of the theoretical background of the tools they choose to use, in order to optimally facilitate learning and make the best of the simulation, taking into consideration that it is a costly, as well as a time- and resource-consuming, teaching method.5

There are several theoretical perspectives, which can inform utilization of simulation in medical education. They include behaviorism, Dewey and Kolb’s experiential learning, Bruner’s constructivist theory, Shon’s reflective practice theory, situated learning theory described by Lave and Wenger as well as critical theories and Hamstra’s functional task alignment theory,6,7,8,9,10,11,12 the extensive discussion of which is beyond the scope of this chapter.

DESIGNING AND FACILITATING SIMULATION EVENTS

From practical point of view simulation activity design consists of five phases: (1) preparation, (2) briefing, (3) simulating, (4) debriefing (5) evaluating. The phases are summarized in Table 1.

1

Phases of simulation.

Phase | Stages | Actions |

Preparation | Alignment with the curriculum |

|

Scenario design |

| |

Faculty recruitment or training |

| |

Simulated patient training |

| |

Booking resources |

| |

Performing mock simulation |

| |

Briefing | Logistical information about simulation event |

|

Case briefing |

| |

Simulation |

| |

Debriefing/ | Choosing the strategy for performing debriefing; consider using video-assisted debriefing Make good use of debriefing | |

Evaluation | Preparation of evaluation strategy |

|

Making use of evaluation results |

|

Various equipment is available to aid in the delivery of SBE activities and can be adapted to what is available in each training center. They are listed in Table 2.

2

Available equipment in the delivery of pediatric and adolescent gynecology simulation-based education activities.

Type of equipment | Goal of equipment | Examples of equipment |

Part-task trainers (PTTs) | Teaching psychomotor, procedural and technical skills |

|

Whole- or part-body manikins | Teaching complex tasks such has fetal resuscitation |

|

Virtual reality and haptic systems | Teaching simple and complex surgical procedures |

|

High-fidelity simulations | Teaching complex tasks as well as non-technical skills such as team communication, situational awareness |

|

Teaching cognitive and psychomotor skills including critical thinking skills and crisis management | Online use with software employing standard cloud-based platforms

| |

Teaching decision making, critical thinking and clinical reasoning through making users believe they are in a different environment |

|

BRIEF REVIEW OF SIMULATION IN OBSTETRICS AND GYNECOLOGY

Specific literature in SBE relating to obstetrics and gynecology was first published in 2005. The first studies looked at medical students practicing their gynecological exam on “professional patients”21,22,23 and have progressed to more complex simulations including additional pre-rotation SBE curriculum involving vaginal deliveries, intra-partum cervical exams, suturing, knot tying, speculum and bimanual exams.24,25,26,27

Randomized controlled trials specific to obstetrics and gynecology residents began in 2013 and have shown positive benefits of simulation on resident skills and competence in both the simulated and clinical environments. In 2018, Nippita et al. demonstrated that both low- and high-fidelity models, to teach intrauterine contraception placement, were comparable when comparing placement skills and self-perceived competence and comfort.28 This is of utmost importance in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) where simulation resources may be sparse.

PEDIATRIC AND ADOLESCENT GYNECOLOGY (PAG) EDUCATION AROUND THE WORLD

PAG is a budding sub-speciality of gynecology and fellowship programs are growing across North America and around the world. To access the most updated list of available fellowships in North America, one can access the North American Society of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology (NASPAG) website.29 At the time of publishing this chapter, 16 official PAG fellowship were available across Canada and the United States of America (USA). Additionally, PAG is a recognized specialty by some European Universities in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Greece and France, as well as in Argentina, Venezuela and Chile in Latin America.30 Other universities offer courses without specific fellowships in PAG: almost all the European countries, Hong Kong in China, Australia and New Zealand, India, Philippines and Malaysia. In addition to training PAG fellows, multiple efforts are being made to expose and train gynecology residents in PAG as studies have demonstrated a lack of training and/or inconsistencies amongst residency programs.

Since 1996, researchers in PAG education from around the world have demonstrated a lack of access to PAG training (rotations, clinics, didactics, curriculums) for medical students and residents (in obstetrics and gynecology, pediatric medicine, pediatric surgery and general medicine) and that well designed curriculums as well as better dissemination of available tools can improve the experience and learning31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41 for our trainees.

Given that NASPAG has a mission to “Conduct and encourage multidisciplinary and inter-professional programs of medical education” they developed both short and long curriculums for disciplines that care for the PAG population such as gynecology, pediatric and general practice residents.42,43 A pan-European PAG post-specialty training curriculum with 17 chapters including medical, surgical and baseline skills sections was recently published.44 Small studies have attempted to evaluate the impact of implementing a PAG curriculum in a gynecology residency. All these studies demonstrated an increased comfort in managing PAG patients and some also demonstrated an increase and/or retention in knowledge.45,46,47,48

There are many reasons why PAG is undertaught in residency programs including lack of PAG patients in smaller centers, lack of PAG pathology due to small catchment areas or patients who declined to be examined by trainees, lack of PAG trained-providers to offer educational experiences, lack of PAG surgical exposure, etc. Since identifying this issue, PAG-related educational publications have focused on different educational modalities to palliate the paucity of PAG educational opportunities in residency programs. These modalities include videoconferencing, web-based computerized case series, case-based learning, eLearning modules and PAG simulation.49,50,51,52

ALIGNING SIMULATION-BASED EDUCATION WITH PAG CURRICULA

In order to bring the expected learning benefit, the PAG SBE needs to be carefully aligned and positioned within the overall PAG curriculum. It has been suggested that learners and faculty are more likely to take simulation experiences more seriously, if they are well integrated into the curriculum, the evaluation process, and everyday educational activities.53 In the case of PAG curricula, simulation can be especially valuable to facilitate teaching about rare or sensitive conditions with limited access to real-life patient situations. Using simulators and simulation experiences to address such problems can strengthen the overall curriculum and educational program.

Implementation of simulation activities into the curriculum should be preceded by careful analysis of the learning objectives and content, which are best delivered with this technique, timing of simulation event within the curriculum, academic hours dedicated to SBE, availability of faculty and equipment. It should also be decided a priori if the simulation session will be used solely for teaching and/or for performance assessment.54 Collaboration with the simulation specialist should be considered from the very beginning of curriculum design. The literature suggests that simulation brings best results if it is introduced at different time points and levels of expertise within the curriculum, and that scaffolding the level of challenge motivates and sustains learner engagement.53

The ADDIE model was proposed as an effective framework for developing and maintaining sustainable SBE activity within any curriculum. It consists of five steps that occur iteratively: assess/analyze, design, develop, implement/deliver, evaluate. The detailed description of this models is beyond the scope of this chapter, further readings are available in the reference section.55

SIMULATION-BASED EDUCATION IN PAG

Simulation has been developed in many fields to palliate the paucity of resident access to certain types of patient encounters, exams, procedures and surgery. The same holds true of PAG. Various simulation models and curriculums have been developed over the past decade by passionate PAG providers and educators. In Table 3, the available literature on SBE in PAG in summarized.

3

Summary of current literature of simulation-based education in pediatric and adolescent gynecology (PAG).

Year, location and first author | Competency evaluated | Type of trainer used | Outcomes of the study |

2009, Israel, Beyth56 | Communication with adolescents | Simulated patients | Satisfaction rate of the participants was so high that they recommended this program be expanded to all gynecologists and residents in gynecology. |

2011, USA, Loveless57 | PAG gynecological exam, collection of microbial cultures, vaginal lavage, vaginoscopy | Simulated pelvis | Significant improvement in scores pre- and post-training and this improvement in knowledge and scores was found to be consistent amongst all years of residency. |

PAG history taking, genital examination, Tanner staging, vaginal sampling and flushing, hymenectomy, vaginoscopy, laparoscopic adnexal detorsion | Part-task trainers: breasts, pelvis, abdomen | All residents agreed that they gained self-perceived knowledge and that the simulation curriculum should be implemented as a recurrent part of their curriculum; all resident agreed that a simulation scenario focussed on child/adolescent communication should be included in the curriculum; mean OSCE score increased from 54.6% to 78.1% thus concluding the positive impact of this simulation curriculum on resident history taking, examination skills, operative techniques and approach to the PAG population | |

2015, USA, Damle60 | Pediatric mannequin with anatomic pre-pubertal genitalia | Residents who were in the simulation group did as well as those on rotation and better than the controls. This reinforces the need to implement PAG simulation curriculums into all residency training programs as simulation can palliate the lack of PAG clinics, OR exposure and clinical rotations. | |

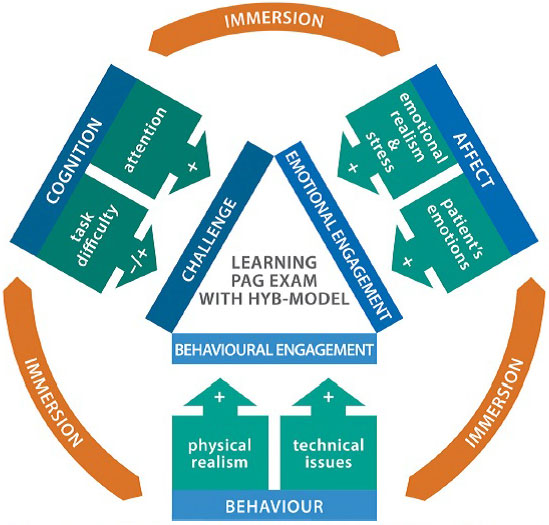

Self-assessed skills in PAG examination | High-fidelity hybrid model (pelvic trainer + simulated patient + simulation gynecology office | All participants recommended the hybrid model; residents valued the hybrid model in all three components that were assessed (cognitive, affective and behavioral). This was a mixed-methods study the qualitative assessment of which from interviews uncovered six themes that affect the PAG simulation learning environment: physical realism and perceived difficulty, emotional realism of the patient, emotional states, comparison of difficulty between the two simulation types, engagement with the patient and perception of higher fidelity with the hybrid model. This led to the development of a conceptual model influencing learning with high-fidelity hybrid models in PAG simulation (Figure 1). |

1

The conceptual model illustrating factors influencing learning in hybrid model high-fidelity simulation environment.62

To help the reader understand the different models used to date in SBE in PAG, we have taken samples from the current literature as well as personal collection and explained them in Table 4.

4

Available models in simulation-based education in pediatric and adolescent gynecology.

What to simulate | How to simulate | Picture |

Pediatric perineum (Loveless et al.57) | Cellophane tapped over the perineum to create a “hymen” tension adjusted so the “hymen” is fully visualized only id proper anterior and lateral traction is applied to labia but otherwise obscured as encountered in the pediatric patient |

|

Pediatric pelvic exam in the lab | Undersized pelvic trainer on the lab bench (low fidelity) |

|

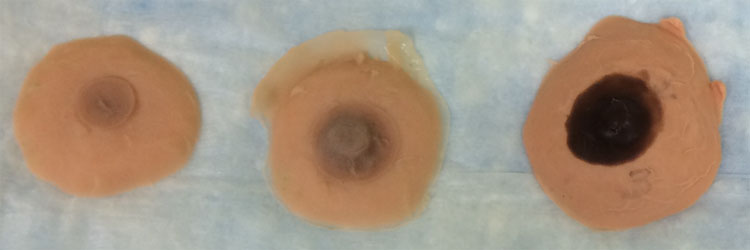

Tanner breast staging (Personal collection, Dumont) | Tanner stages of breast development from 1 to 5 using silicone molding |

|

Tanner breast and pubic hair staging (personal collection share by Nichole Tyson) | Tanner stages of breast development from 1 to 5 using knitted models |

|

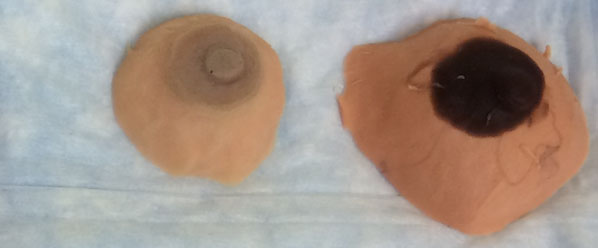

Collection of microbial cultures (Torres et al.)61 | Catheterization trainer with vaginal opening and soft labia minora (e.g. Laerdal, often available in Simulation Centers) |

|

Pediatric pelvic exam: demonstrating positioning, examination techniques, and procedural skills (Damle et al.60) | Life-size toddler doll purchased from a commercial retailer Doll’s hip joints modified to allow for better external rotation and leg positioning |

|

Vaginal canal and cervix created from recycled components of a hysteroscopy model Latex mold used to create external genitalia |

| |

Latex mold draped over doll’s perineum and attached anteriorly and posteriorly above the hips to hold the external anatomy in place (replaceable in case of damage) Costume makeup used to create labial erythema |

| |

Pediatric vulva and hymen (Dumont, personal communication) | Hybrid model with life-sized doll with phone on speaker-mode placed under the gown (in order to make the doll respond to the exam by trainee), wire coat hanger placed into the legs in order to be able to place in frog-leg position and a pediatric vulva and vagina (silicone gel (Dragon skin) molded over a syringe) | |

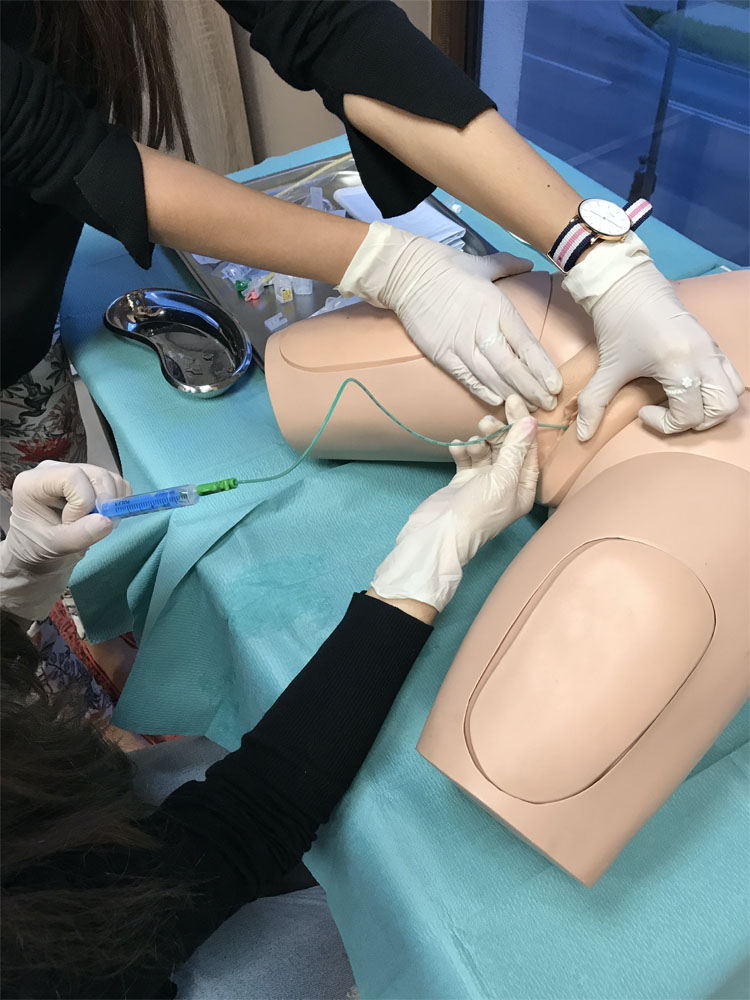

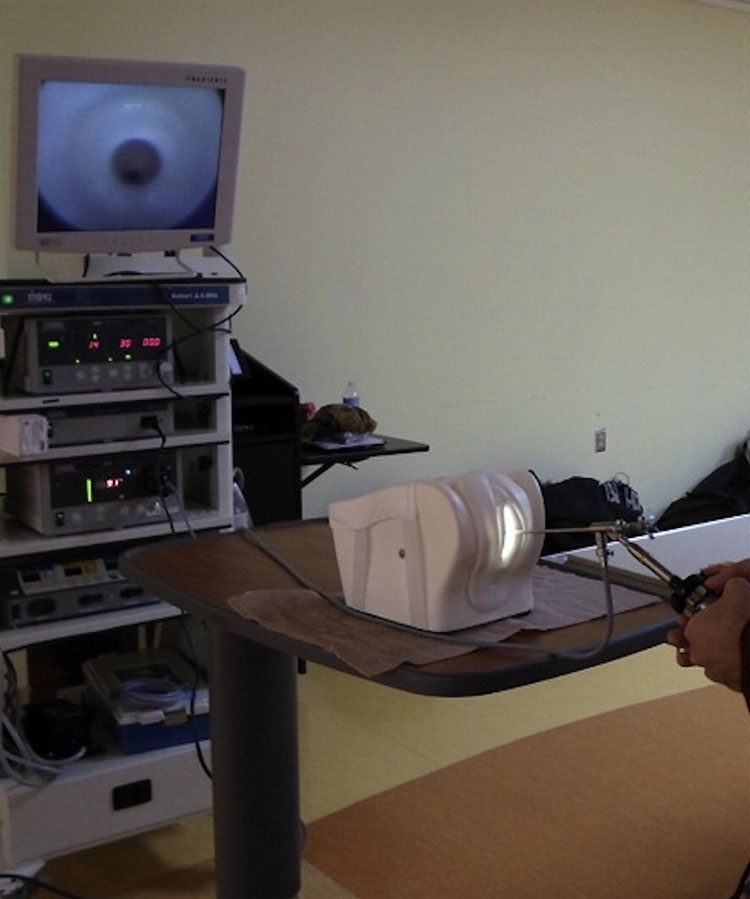

Hybrid model of pelvic exam (Torres et al.62) | Pelvic trainer positioned on the gynecological bed with the SP’s voice and SP caregiver present in the simulated exam room (middle fidelity) |

|

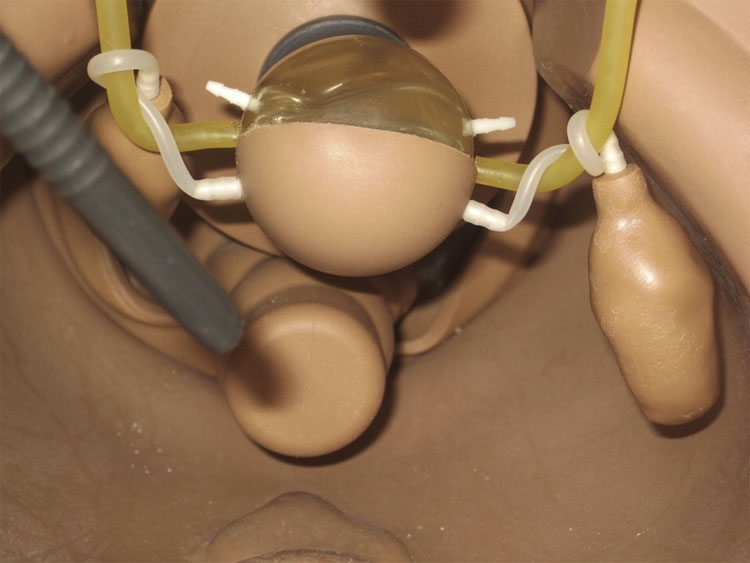

Hybrid model of pelvic exam (Torres et al.62) | Pelvic trainer connected to SP with the SP caregiver present in the simulated exam room (high fidelity) |

|

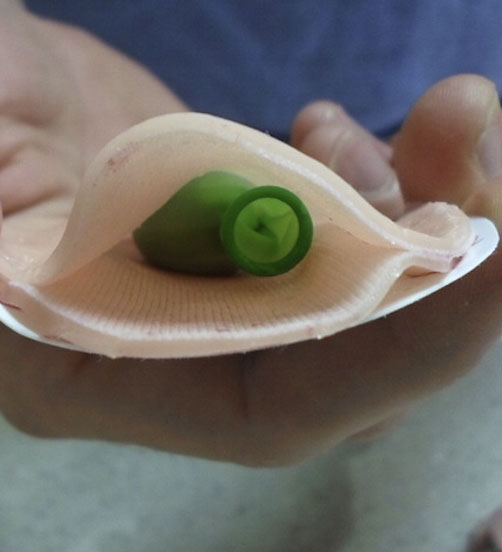

Imperforate hymen (Dumont et al.58) | Two oval shaped silicone skin flaps between which a balloon containing red liquid was placed to mimic an imperforate hymen |

|

Vaginoscopy (Dumont et al.59) | “Retired” cystoscope or hysteroscope |

|

Hybrid model for cystoscopy/ | A bladder model using core-out papaya presented by Nguyen et al. (2015)63 can serve as vagina model for vaginoscopy, it can be placed inside a rubber pelvic model and for higher fidelity it can be connected to the simulated patient |

|

Adnexal torsion (Dumont et al.59) | View of inside the laparoscopic model of the adnexal torsion |

|

THE FUTURE OF PEDIATRIC AND ADOLESCENT GYNECOLOGY SIMULATION-BASED EDUCATION

There are many areas of PAG SBE that require more studies. To date, there are no studies looking at knowledge retention and transferability of PAG acquired skills during simulation training and/or implementation of simulation curriculums to either the clinical setting or high-stakes evaluations. This will be an important area of PAG simulation education to explore in future studies.

Studies are needed to explore the role of simulated patients including the possibility of the use of minors as simulated patients. Additionally, interprofessionalism in SBE in PAG could be introduced and its role explored. PAG SBE should not only be considered for learners but also for the professional development and appraisal of PAG specialist.

Finally, the role of screen-based simulators (SBS) and 3-dimensional virtual reality (3D VR) is a new avenue of SBE and its merits in PAG need to be explored.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- Educational theory should guide practice in simulation-based teaching in PAG.

- SBE should be considered a method of teaching and assessment for both technical and non-technical PAG skills.

- Functional fidelity with excellent instructional design confers to successful learning in simulation environment.

- Program directors, gynecologists and residents should familiarize themselves with the available and published PAG simulation curriculums.

- PAG Simulation curriculums should be implemented into all gynecology residency training programs.

- PAG Simulation curriculums should be tailored to each training center, their available resources and their patient population and should be integrated with the core PAG curriculum.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) of this chapter declare that they have no interests that conflict with the contents of the chapter.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

REFERENCES

Gaba DM. The future vision of simulation in healthcare. Simul Healthc 2007;2(2):126–35. | |

ESGE special interest group ‘quality, safety and legal aspects’ working group, Watrelot AA, Tanos V, et al. From complication to litigation: The importance of non-technical skills in the management of complications. Facts Views Vis Obgyn 2020;12(2):133–9. | |

Ahmed FU, Ijaz Haider S, Ashar A, et al. Non-technical skills training to enhance performance of obstetrics and gynaecology residents in the operating room. J Obstet Gynaecol 2019;39(8):1123–9. | |

Nataraja RM, Webb N, Lopez PJ. Simulation in paediatric urology and surgery. Part 1: An overview of educational theory. J Pediatr Urol 2018;14(2):120–4. | |

Hippe DS, Umoren RA, McGee A, et al. A targeted systematic review of cost analyses for implementation of simulation-based education in healthcare. SAGE Open Med 2020;8:2050312120913451. | |

Ansar A, Rafi A, Rizvi RM. Is behaviourism really dead? A scoping review to document the presence of behaviourism in current medical education. J Pak Med Assoc 2021;71(4):1214–20. | |

Kolb DA. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development, 2nd Edn. 2015. | |

Lave J, Wenger E. Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press, 1991. | |

Mcgaghie WC, Issenberg SB, Barsuk JH, et al. A critical review of simulation-based mastery learning with translational outcomes. Med Educ 2014;48:375e85. | |

Fosnot CT, Perry RS. Constructivism: A psychological theory of learning. Constructivism: Theory, Perspectives Pnd practice 1996;2(1):8–33. | |

Sandars J. The use of reflection in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 44. Med Teach 2009;31(8):685e95. | |

Hamstra SJ, Brydges R, Hatala R, et al. Reconsidering fidelity in simulation-based training. Acad Med 2014;89(3):387–92. | |

Sawyer T, Eppich W, Brett-Fleegler M, et al. More Than One Way to Debrief: A Critical Review of Healthcare Simulation Debriefing Methods. Simul Healthc 2016;11(3):209-17. | |

Eppich W, Cheng A. Promoting Excellence and Reflective Learning in Simulation (PEARLS): development and rationale for a blended approach to health care simulation debriefing. Simul Healthc 2015;10(2):106-15. | |

Rudolph J, Simon R, Dufresne R, et al. There’s no such thing as ‘‘nonjudgmental’’ debriefing: a theory and method for debriefing with good judgment. Simul Healthc 2006;1(1):49Y55. | |

Zigmont JJ, Kappus LJ, Sudikoff SN. The 3D model of debriefing: defusing, discovering, and deepening. Semin Perinatol 2011;35(2):52Y58. | |

Michelet D, Barré J, Job A, Truchot J, Cabon P, Delgoulet C, Tesnière A. Benefits of Screen-Based Postpartum Hemorrhage Simulation on Nontechnical Skills Training: A Randomized Simulation Study. Simul Healthc 2019;14(6):391–7. doi: 10.1097/SIH.0000000000000395. PMID: 31804424. | |

Chang TP, Weiner D. Screen-based simulation and virtual reality for pediatric emergency medicine. Clinical Pediatric Emergency Medicine 2016;17(3):224–30. | |

Pottle J. Virtual reality and the transformation of medical education. Future Healthc J 2019;6(3):181–5. doi: 10.7861/fhj.2019-0036. PMID: 31660522; PMCID: PMC6798020. | |

Issenberg SB, McGaghie WC, Petrusa ER, et al. Features and uses of high-fidelity medical simulations that lead to effective learning: a BEME systematic review. Med Teach 2005;27(1):10–28. | |

Wanggren, K., et al. "Teaching medical students gynaecological examination using professional patients-evaluation of students' skills and feelings". Medical Teacher 2005;27(2):130–5. | |

Wanggren, K., et al. "Teaching pelvic examination technique using professional patients: a controlled study evaluating students' skills". Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 2010;89(10):1298–303. | |

Janjua A, et al. "Cost-effective analysis of teaching pelvic examination skills using Gynaecology Teaching Associates (GTAs) compared with manikin models (The CEAT Study)". BMJ Open 2018;8(6):e015823. | |

Mitric C, et al. "Impact of a Multidimensional Technical Skills Training Session Before Obstetrics and Gynaecology Clerkship Rotation on Performance and Exposure". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada: JOGC = Journal d'Obstetrique et Gynecologie du Canada: JOGC 2018;40(10):1315–23. | |

Gala R, et al. "Effect of validated skills simulation on operating room performance in obstetrics and gynecology residents: a randomized controlled trial". Obstetrics and Gynecology 2013;121(3):578–84. | |

Shore EM, et al. "Validating a standardized laparoscopy curriculum for gynecology residents: a randomized controlled trial". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2016;215(2):204.e201–11. | |

Patel NR, et al. "Traditional Versus Simulation Resident Surgical Laparoscopic Salpingectomy Training: A Randomized Controlled Trial". Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology 2016;23(3):372–7. | |

Nippita S, et al. "Randomized trial of high- and low-fidelity simulation to teach intrauterine contraception placement". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2018;218(2):258.e251–11. | |

Muram D, et al. "Teaching pediatric and adolescent gynecology: a pilot study at one institution". Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology 1996;9(1):12–5. | |

Wagner EA, et al. "Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology experience in academic and community OB/GYN residency programs in Michigan". Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology 1999;12(4):215–8. | |

Solomon ER, et al. "Residency training in pediatric and adolescent gynecology across obstetrics and gynecology residency programs: a cross-sectional study". Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology 2013;26(3):180–5. | |

Dumont T. "The Current State of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology Residency Training in Canada: A Needs Assessment From Program Directors". J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2021. | |

Solotke MT, et al. "Establishing a Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology Subinternship for Medical Students". Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology 2020;33(2):104–9. | |

Korczak DJ, et al. "Canadian pediatric residents' experience and level of comfort with adolescent gynecological health care". The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine 2006;8(1):57–9. | |

Cosgrave EJ, et al. "Identifying a Knowledge Deficit among Pediatric and General Practitioner Trainees in Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology in an Irish Hospital: A Pilot Study". J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2021;34(5):631–4. | |

Justice TD, et al. "Is there a need for a formal gynecology curriculum in a pediatric surgery training program? A needs assessment". Journal of Pediatric Surgery 2020;55(5):904–7. | |

Rosen MW, et al. "Pediatric Resident Training in Prepubertal Vulvar Conditions". Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology 2018;31(1):7–12. | |

Shah B, et al. "Teaching Trainees to Deliver Adolescent Reproductive Health Services". Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology 2016;29(1):53–61. | |

Kershnar R, et al. "Adolescent medicine: attitudes, training, and experience of pediatric, family medicine, and obstetric-gynecology residents". The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine 2009;82(4):129–41. | |

Gibson MES, et al. Resident Education Curriculum in Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology: The Short Curriculum 3.0. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology 2021;34(3):291–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2021.01.016. Epub 2021 Mar 30. PMID: 33810968. | |

French AV, Alaniz V, Dumont T, et al. Long Curriculum 3.0 in Resident Education: Comprehensive Curriculum in Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology for Postgraduate Trainees in Obstetrics/Gynecology, Pediatrics, and Adolescent Medicine. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2022:S1083-3188(21)00366-1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2021.12.017. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34999228. | |

Mourik SL, et al. "The new pan-European post-specialty training curriculum in Paediatric and Adolescent Gynaecology". European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 2021;258:152–6. | |

Hirai CM, et al. "Perceptions Regarding Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology Training among Obstetrics and Gynecology Residents in Hawai'i". Hawaii J Health Soc Welf 2021;80(8):179–83. | |

Palaszewski DM, et al. "Impact of a Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology Curriculum on an Obstetrics and Gynecology Residency". Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology 2016;29(6):668–72. | |

Huguelet PS, et al. "Does the North American Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology Short Curriculum Increase Resident Knowledge in Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology?" Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology 2016;29(6):623–7. | |

Huguelet PS, et al. "Improving Resident Knowledge in Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology: An Evaluation of the North American Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology Short Curriculum". Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology 2018;31(4):356–61. | |

De Silva NK, et al. "Pediatric and adolescent gynecology learned via a Web-based computerized case series". Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology 2010;23(2):111–5. | |

Dietrich JE, et al. "Reliability study for pediatric and adolescent gynecology case-based learning in resident education". Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology 2010;23(2):102–6. | |

Spitzer RF, et al. "Videoconferencing for resident teaching of subspecialty topics: the pediatric and adolescent gynecology experience at the Hospital for Sick Children". Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology 2008;21(6):343–6. | |

Huguelet PS, et al. "Association of a Pediatric Gynecology eLearning Module With Resident Knowledge and Clinical Skills: A Randomized Controlled Trial". Obstetrics and Gynecology 2020;136(5):987–94. | |

Issenberg SB, McGaghie WC, Petrusa ER, et al. Features and uses of high-fidelity medical simulations that lead to effective learning: a BEME systematic review. Med Teach 2005;27(1):10–28. | |

Castro D, Tcharmtchi MH, Thammasitboon S. A Practical Application of Educational Theories in Developing a Boot Camp Program for Pediatric Critical Care Fellows. Acad Pediatr 2016;16(8):707–11. | |

Tseng LP, Hou TH, Huang LP, et al. Effectiveness of applying clinical simulation scenarios and integrating information technology in medical-surgical nursing and critical nursing courses. BMC Nurs 2021;20(1):229. doi: 10.1186/s12912-021-00744-7. PMID: 34781931; PMCID: PMC8591873. | |

Beyth Y, Hardoff D, Rom E, et al. A simulated patient-based program for training gynecologists in communication with adolescent girls presenting with gynecological problems. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2009;22(2):79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2007.11.002. PMID: 19345912 | |

Loveless MB, Finkenzeller D, Ibrahim S, et al. A simulation program for teaching obstetrics and gynecology residents the pediatric gynecology examination and procedures. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2011;24(3):127–36. | |

Dumont T, Hakim J, Black A, et al. Does an Advanced Pelvic Simulation Curriculum Improve Resident Performance on a Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology Focused Objective Structured Clinical Examination? A Cohort Study. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2016;29(3):276–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2015.10.015. Epub 2015 Oct 29. PMID: 26537315. | |

Dumont T, Hakim J, Black A, et al. Enhancing postgraduate training in pediatric and adolescent gynecology: evaluation of an advanced pelvic simulation session. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2014;27(6):360–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2014.01.105. Epub 2014 Sep 23. PMID: 25256870. | |

Damle LF, Tefera E, McAfee J, et al. Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology Education through Simulation (PAGES): Development and Evaluation of a Simulation Curriculum. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2015;28(3):186–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2014.07.008. Epub 2014 Jul 22. PMID: 26046608. | |

Torres A, Horodeńska M, Witkowski G, et al. High-Fidelity Hybrid Simulation: A Novel Approach to Teaching Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2019;32(2):110–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2018.12.001. Epub 2018 Dec 7. PMID: 30529700. | |

Torres A, Horodeńska M, Witkowski G, et al. Hybrid simulation of pediatric gynecologic examination: a mix-methods study of learners' attitudes and factors affecting learning. BMC Med Educ 2020;20(1):164. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02076-7. PMID: 32448304; PMCID: PMC7245870. | |

Nguyen LN, Tardioli K, Roberts M, et al. Development and incorporation of hybrid simulation OSCE into in-training examinations to assess multiple CanMEDS competencies in urologic trainees. Can Urol Assoc J 2015;9(1–2):32–6. | |

McGaghie WC, Issenberg SB, Petrusa ER, et al. A critical review of simulation-based medical education research: 2003–2009. Med Educ 2009;44:50e63. | |

Anders Ericsson K. Deliberate practice and acquisition of expert performance: a general overview. Acad Emerg Med 2008;15:988e94. | |

Anderson JM, Aylor ME, Leonard DT. Instructional design dogma: creating planned learning experiences in simulation. J Crit Care 2008;23(4):595–602. | |

Kolb DA. Experimental learning. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall, 1984. | |

Schon D. Educating the reflective practitioner. London: Jossey-Bass, 1987. | |

Nestel D, Kelly M, Jolly B, et al. Healthcare simulation education: evidence, theory and practice. John Wiley & Sons, 2017. | |

Burden C, et al. "Integration of laparoscopic virtual-reality simulation into gynaecology training". BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2011;118(Suppl 3):5–10. | |

Larsen CR, et al. "The efficacy of virtual reality simulation training in laparoscopy: a systematic review of randomized trials". Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 2012;91(9):1015–28. | |

Vaccaro CM, et al. "Robotic virtual reality simulation plus standard robotic orientation versus standard robotic orientation alone: a randomized controlled trial". Female Pelvic Medicine & Reconstructive Surgery 2013;19(5):266–70. | |

Larsen CR, et al. "The efficacy of virtual reality simulation training in laparoscopy: a systematic review of randomized trials". Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 2012;91(9):1015–28. | |

Tolsgaard MG, et al. "The Effects of Simulation-based Transvaginal Ultrasound Training on Quality and Efficiency of Care: A Multicenter Single-blind Randomized Trial". Annals of Surgery 2017;265(3):630–7. | |

Tolsgaard MG. "Assessment and learning of ultrasound skills in Obstetrics & Gynecology". Danish Medical Journal 2018;65(2). | |

Tolsgaard MG. "A multiple-perspective approach for the assessment and learning of ultrasound skills". Perspectives on Medical Education 2018;7(3):211–3. | |

Taksoe-Vester C, et al. "Simulation-Based Ultrasound Training in Obstetrics and Gynecology: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Simulationsbasiertes Ultraschalltraining in Geburtshilfe und Gynakologie: Eine systematische Ubersicht und Metaanalyse. 2020. | |

Romano M, et al. "Long Curriculum in Resident Education: Comprehensive Curriculum in Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology for Postgraduate Trainees in Obstetrics/Gynecology, Pediatrics, and Adolescent Medicine". Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology 2019;32(5):469–80. | |

Diamond RM. Designing and improving courses and curricula in higher education. San Francisco (CA): Jossey-Bass, 1989. | |

Rothwell WJ, Kazanas HC. Mastering the instructional design process: a systematic approach, 2nd edn. San Francisco (CA): Jossey-Bass, 1998. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards programme CLICK HERE)