This chapter should be cited as follows:

McKernan J, Greene RA, et al., Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.412413

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Obstetrics Module

Volume 3

Elements of professional care and support before, during and after pregnancy

Volume Editor: Professor Vicki Flenady, The University of Queensland, Australia

Chapter

Electronic Health/Medical Records in Obstetric and Perinatal Care

First published: February 2021

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

INTRODUCTION

Every year more and more electronic health records (EHRs) are being introduced in Europe, North America, Australasia and the Middle East. The change from paper to electronic records has not always been a seamless or quick process; however, EHRs are viewed as central to updating modern medicine especially regarding organization structures and delivery of sustainable care.1 Globally agencies are moving towards a more sustainable and holistic approach for the development and implementation of e and mhealth healthcare strategies.2 International researchers are now examining the emerging opportunities of eHealth in maternal health. Campanella et al. (2016) defines the electronic health record (EHR) as “a systematic electronic collection of health information about patients such as medical history, medication orders, vital signs, laboratory results, radiology reports, and physician and nurse notes”3 Menachemi and Collum comment that the EHR has the potential to alter healthcare systems from a mostly paper-based industry. They suggest that the EHR allows providers to deliver a higher quality of care.4 The EHR is seen as a tool that will measure quality of healthcare and monitor ongoing provider performance. It will allow for the elimination of expensive and time-consuming processes.5 Boonstra et al. note that the implementation of hospital-wide EHR systems can be a complex matter.6 The authors carried out a systematic review on implementation of an EHR in hospitals. Twenty-one articles met their selection criteria. They commented that implementation needs a range of organizational and technical factors that include human skills, organizational structure, culture, technical infrastructure, financial resources, and coordination.6 The initiative, led by the Norwegian Institute of Public Health and the WHO Department of Reproductive Health and Research (RHR), with Queensland University, the University of Oxford, and the Health Information Systems Program Vietnam, is setting out a framework and tools for introduction of a system of eRegistries. The authors note that eRegistries have functionalities that provide the “potential to go far beyond simple registration tools, and constitute an entire ecosystem of public health information and communication strategies”

The potential of registries may assist those who have not fully transitioned from paper based health information and they could provide an integrated electronic backbone.7

This chapter outlines the development of EHRs, examining how they evolved, the global perspective, the users, and examines literature on the use of paper records versus electronic records. The chapter then examines the planning, implementation and the optimization of an EHR for all women and babies in maternity services; using as a model the experience in Ireland: The Maternal & Newborn Clinical Management System (MN-CMS).

TERMINOLOGY

For this chapter the terminology EHR is used. When reading information regarding electronic records two definitions are used frequently:

- Electronic medical records (EMR)

- Electronic health records (EHR)

The EMR examines a patient’s medical history and is used by providers for diagnosis and treatments. The EHR is designed to be shared outside the individual practice and allows a patient’s information to be updated from specialities, to laboratories and imaging facilities, etc. The EHR provides information on the overall health of the patient.8 The terminology used for EHR is a language in itself and some phrases are new to clinicians and patients. Table 1 contains a short glossary of terms that are frequently used.

1

Glossary of frequently used terms in electronic health records (EHR).

Alerts | Pop-ups or reminders. An automated warning system such a clinical alerts, preventive health maintenance, medication interactions, etc.9 |

Bandwidth | A data transmission rate; the maximum amount of information (bits/second) that can be transmitted along a channel9 |

(CDR) Clinical data repository | A real-time database that consolidates data from a variety of clinical sources to present a unified view of a single patient. It is optimized to allow clinicians to retrieve data for a single patient rather than to identify a population of patients with common characteristics or to facilitate the management of a specific clinical department9 |

CCIO | Chief clinical information officer |

CMIO | Chief medical information officer |

CPOE | Computer provider order entry The most important function of CPOE is to make it easy for the provider to do the correct thing for the patient and difficult to do the wrong thing for the patient10 |

Data integrity | Refers to the validity of data. A condition in which data have not been altered or destroyed in an unauthorized manner9 |

Data mining | The process of analyzing or extracting data from a database to identify patterns or relationships9 |

Data structure | A way to store and organize data in order to facilitate access and modifications9 |

Database | A collection of information organized in such a way that a computer program can quickly select desired pieces of data9 |

Digital signature | Digital signature takes the traditional hand-written signature and creates a digital image of the signature to eliminate the need to print and sign documents.9 Another approach taken is a build identifier: this is a medical licence number and name attached to a login |

Documentation | The process of recording information9 |

eHealth | eHealth is the use of information and communication technologies (ICT) for health11 |

Encryption | Process of converting messages or data into a form that cannot be read without decrypting or deciphering it9 |

e-Prescribing | Prescribing medication through an automated data-entry process and transmitting the information to participating pharmacies9 |

Information governance | The specification of decision rights and an accountability framework to ensure appropriate behavior in the valuation, creation, storage, use, archiving and deletion of information. It includes the processes, roles and policies, standards and metrics that ensure the effective and efficient use of information in enabling an organization to achieve its goals12 |

Patient portal | Allow patients and providers to communicate over the internet in a secure environment9 |

SNOMED CT® (Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine – Clinical Terms) | SNOMED CT is a clinical, healthcare terminology and infrastructure. SNOMED CT contains over 366,170 healthcare concepts with unique meanings and formal logic-based definitions organized into hierarchies9 |

Webinar | A lecture, presentation, workshop or seminar that is transmitted over the web. Short for web-based seminar9 |

Workflow | The automation of a process, in whole or part, during which documents, information or tasks are passed from one participant to another for action, according to a set of procedural rules9 |

THE EVOLUTION OF THE ELECTRONIC HEALTH RECORD

For centuries, health records were written on paper, maintained in folders divided into sections, and only one copy was available. In the 1950s the computer began to replace traditional methods of accounting and book-keeping.13 The further development of computer software and hardware developments to allow computers to be progress as data processors in the 1960s and 1970s laid the foundations for the development of the EHR. At this time academic medical centers initiated systems that compiled patient health information that could be shared and managed at a central point.14 Countries have taken different approaches to the deployment of the EHR; some have home grown systems in single organizations for example in the US; to interoperability standards for linking multiple information technology (IT) systems; to top-down, government driven, national implementations of standardized systems.15 The UK, Australia and France have developed a national electronic medical record system.16 A number of reasons have emerged suggesting why EHRs were not widely implemented across healthcare systems: these include high costs, data entry errors, poor initial physician acceptance and lack of real incentive. To develop and implement an EHR at the time would have been costly and the benefits may not have been widely shown. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the IT world was changing and software and hardware were becoming more affordable. The emergence of hand-held devices, mobile devices and the internet played a part in moving the EHR towards a cost-effective widely used record.15 For some countries the move towards EHRs is only at the beginning, and while benefits are being noted for population health projects in countries with well-established projects there are still issues that have not been addressed. These include healthcare coverage, privacy, and especially the security of EHRs. There is an increasing demand from patients that they know their data are secure and safe.17 Healthcare providers need to be able to provide assurance that measures are being put in place to ensure data security. The EHR produces vast quantities of data offering enormous opportunity for research towards improving care; however, the secondary use of data must be carried out ethically and with the knowledge of the patient.15 The world has radically transformed through digital innovation in most areas of modern life.

A GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE OF THE ELECTRONIC HEALTH RECORD IN 2018

EHRs are supplied by a number of international companies and the global share of the market is growing rapidly. The main organizations supplying EHRs worldwide include AdvancedMD, Inc., Allscripts Healthcare Solutions, Inc., Cerner Corporation, Computer Programs and Systems, Inc., CureMD Corporation, eClinicalWorks, Epic Systems Corporation, General Electric Company, Greenway Health, LLC, and Quality Systems, Inc.18 Nguyen et al. noted in 2014 that there would be an estimated increase in the implementation of EHRs in North America, by 9.7%, in the Asia Pacific region by 7.6% and in Europe, Africa and Latin America, EHR adoption will increase by 6.6%. In 2010 the market value of EHRs/EMRs was estimated at $15.5 billion and is projected to grow to $19.7 billion.19 The market share is projected to continue to grow in the coming years.

ADVANTAGES AND DISADVANTAGES OF THE ELECTRONIC HEALTH RECORD

The digital world has evolved greatly in the past two decades. Over half the world’s population are now online and two-thirds of the world’s population have a mobile phone.20 The requirement for data has changed. The move towards EHRs has allowed massive amounts of data to be captured and now we must use these data and turn them into knowledge.21 Data are available for use by numerous people across one organization, in the same instant. The data can be easily accessible and can be manipulated in a number of ways for clinical reasons, audit, research, management and financial planning.22

There are advantages and some disadvantages of the EHR, the advantages include timeliness, availability, completeness, legibility and (ideally) accuracy. Potential improvements in population health include EHRs ability to organize and analyze a large amount of patient information.23 The cost of storing and accessing paper charts can be a financial burden on organizations. Disadvantages of the EHR include the disruption to workflow as the EHR is being implemented, negative emotions, medical errors and overdependence on technology.4 For the patient, security measures need to be put into place to ensure that data breaches do not occur. The technology allows for data to be shared across different platforms hence the structure is more susceptible to data breaches.24

EHEALTH STRATEGIES

A consistent national approach has not been taken for the implementation of EHRs. Countries have taken either a national approach, or EHRs have developed for a medical center or medical organization. The approach taken usually depends on how the healthcare service is provided and how it is paid for. In the US, a national approach has not been adopted and EHRs or EMRs vary from state to state or medical center to medical center. US Government incentives have attempted to increase the development of the EHR. The Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 was signed in to law in 2009 and gave greater incentives to hospitals and healthcare facilities to use health information technology. The adoption of EHRs has been slow and issues cited have included implementation issues, optimization issues, interoperability and cyber security.23 The UK initiated a project in 2002: National Program for Information Technology. This project attempted to create a national health record system for the entire UK. The project, however, was unsuccessful due to overambitious timescales, poor user experience and the growing cost.23 The lesson learned for the UK was that a country’s size and current health system does influence the implementation for the project.

The French government had varied success with the implementation of the EHR and after the initial unsuccessful attempt a small working group was formed to advise on the program's continuation. A new policy was implemented in 2013 and passed through legislation in 2016. The DMP (Dossier Médical Partagé/ Personal Medical Record project) is a patient centered EHR that allows the patient to interact with the record. The idea of the DMP is that it remains under the control of the patient.16 A number of countries have had varied success with the implementation of the EHRs.

The World Health Organization engaged with the advancement of the eHealth/EHR by providing a national eHealth strategy toolkit for governments and countries to develop a structured comprehensive guide for eHealth for patients.11 Ireland like many other countries produced an eHealth strategy. The strategy published in 2013 outlines the Irish Health Service Executive (which provides public health and social care services to anyone living in Ireland) and the Irish Government’s Department of Health eHealth goals. The purpose of the strategy was to demonstrate how the individual citizen, the Irish healthcare delivery systems – both public and private – and the economy as a whole could benefit from eHealth.22

The strategy aims to outline how the proper introduction and utilis]zation of eHealth will ensure:

- The patient is placed at the center of the healthcare delivery system and becomes an empowered participant in the provision and pursuit of their health and well-being

- The successful delivery of health systems reform and the associated structural, financial and service changes are planned

- The realization of health service efficiencies including optimum resource utilization

- Ireland’s healthcare system can respond to the challenge defined by the EU task force report – Redesigning health in Europe for 2020 – to ensure that in the future all EU citizens have access to a high level of healthcare, anywhere in the Union, and at a reasonable cost to our healthcare systems.

- The potential of eHealth as a driver for economic growth and development can be realized.22

The strategy document outlines how other countries have implemented eHealth projects and it also provides an economic impact analysis. The strategy document acknowledges that an aging population and the need to restructure the Irish healthcare system provide challenges to reaching its overall goals.22

ELECTRONIC HEALTH RECORD IN IRELAND

The Maternal & Newborn Clinical Management System (MN-CMS) project is the design and implementation of an EHR for all women and babies in maternity services in Ireland.25 This is the first national project undertaken in the Republic of Ireland to implement an EHR. The clinical lead for obstetrics of the MN-CMS project outlines the objectives as:

- Implementing a fully integrated maternal and newborn clinical management system to support the business and service objectives of the hospital

- Phasing out of the paper chart into the EHR

- Integrating the EHR with all required 3rd party systems

- Implementing the necessary infrastructure to support the project

- Training all staff required to use the system in an appropriate manner

- Maintenance and support.

The Maternal & Newborn Clinical Management System national project team recorded their key findings in their phase 1 closure report. This essential report outlines the stages of phase 1 including lessons learned and key recommendations for the next phase of the project. This report is summarized below highlighting key elements that can be used widely. The national obstetric lead provided anecdotal evidence of phase 1 of the project.

Planning a national system using Maternal & Newborn Clinical Management System (MN-CMS) as an example, including the lessons learned and barriers experienced

For the MN-CMS program, a board was set up with the aim to develop a national obstetric and neonatal record for all women and babies in Ireland. The board comprised of stakeholders from the Institute of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, the Faculty of Pediatrics, nursing and midwifery staff, pharmacology personnel, Department of Health personnel, healthcare IT and healthcare managers. As the project progressed other stakeholders were recognized and invited to participate these included general practitioners and anesthetists. The main aim of the board was to provide oversight to procure an EHR. This was the start of a change-management project across the maternity services in the Republic of Ireland. The project was greater than an IT project as it included changes across all aspects of maternity services. This project involved moving all maternity units over time to one linked EHR. The project included moving from predominantly paper-oriented hospitals to electronic hospitals. The principles set out by the board ensured that the mother and baby were at the center, information would be collected once only and that the EHR would record practice, not decide practice.

The first step for the board was to carry out a needs assessment. A group comprising of members of the board and senior healthcare managers carried out the needs assessment. The assessment included the 19 maternity units in Ireland and following the assessment a detail design specification was carried out. In 2011 the public procurement process was commenced, and contracts were signed in 2014. Cerner was chosen as the preferred vendor and the MN-CMS team initiated the implementation program in 2014.26

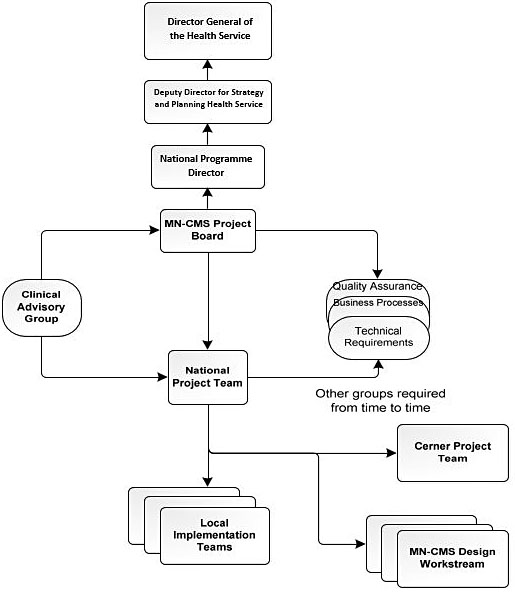

The MN-CMS national board ensured that a governance structure was in place to guarantee a successful roll-out of the service. The governance structure is outlined below (Figure 1). The rollout (phase 1) initially took place in four units from 2016 and is continuing with five units per phase.26 There is not an end date specified as the completion of the project is determined by the availability of public funding.

1

EHR – Governance model.

- Suggested key points for the planning phase of an EHR

Engage key stakeholders early in the process - Strong leadership including clinical leadership is needed for decision-making

- Take time for the procurement process

- Set up a governance structure

- Communicate with staff about the project and engage with interested parties

- Remember to keep the patient at the center of the project at all times

Implementing a national system using Maternal & Newborn Clinical Management System (MN-CMS) as an example, including the lessons learned and barriers experienced

After the contracts were signed the board set up a project team. This project team had responsibility for the implementation of phase 1 of the rollout. Clinicians were at the center of this team and were instrumental in all elements of the project.

The team included the following personnel:

- Program manager

- Clinical director

- Neonatal lead

- Obstetric lead

- Order communications lead

- Two business implementation managers

As the project progressed local project managers usually at midwifery management level were appointed in each of the four initial maternity sites. In each unit a local implementation team was established. A workstream was set up for each clinical area. These workflow included aspects of care such as the booking visit, elective and emergency cesarean section workflows, stillbirth and neonatal death, blood transfusion and NICU admission.26

The implementation stages included:

- Current state analysis – The workstreams working with the national project team and Cerner completed a current state analysis of the existing workflows in each hospital. All workflows were mapped from the first phase 1 units. This included mapping the patient journey from the first referral to the hospital for care to the discharge process following delivery. Between the maternity and NICU work streams on average approximately 54 workflows were mapped by each hospital.26

- Future state analysis – The current state analysis was used to provide a starting point for the future state analysis – workflows in the new electronic environment. All workflows were considered and a design was based on best practice across all sites using multiple multidisciplinary workstreams.26

- Design & build – A collaborative approach was taken for the design and build phase, this saw the national project team, the vendor and the workstream personnel working together. This phase of the project proved challenging due to the complexity involved in designing and building a comprehensive EHR and as the workstreams had representatives from all 19 units. The recommendations made were fed back to the national team and the vendor. A smaller group made up of clinicians and subject matter experts made final decisions on the design and Cerner then completed the configuration and build.26

- Future state validation – At the end of the design and build phase the project was presented by the national project team and the workstream personnel to maternity services staff. It was an opportunity for attendees to get some hands-on experience of the system and gain an understanding of how it would work in their hospital.26

- Design changes – Once the design & build phase closed, there were strict change control protocols put in place. Weekly meetings are held to manage and review change requests. As multiple users are and will be using the system one change for one unit may not be acceptable in another, all changes need to be agreed by all units before being implemented.26

- Testing – The testing phase included system testing and integration testing. System testing involved testing the system against the workflows to ensure the design was functioning as expected. Test scripts were created to test the various scenarios that might occur for both the mother and the baby. Integration testing included the interfaces to the third-party systems (system demographics) and laboratory systems (orders and results). The test phases happened in each hospital as the workflows needed to be validated and to ensure the third-party systems in their individual sites functioned as expected. Integration testing also included the testing of wristbands, bar code scanners and the printing solutions. Device association for the neonatal monitors and ventilators and the fetal monitoring (cardiotocograph monitoring) solution – FetaLink (FetaLink provides a graphical display of the relationship between fetal heart rates and contraction data in the EHR. It displays waveforms and annotations, which can be viewed in real-time by care providers in inpatient or outpatient settings)27 were all tested during this testing cycle. The Downtime System Access Viewer (7/24) used to view the patient chart in the event of a planned or unplanned downtime also had to be tested at each site.26 Testing issues were logged to an online portal open to the project team and provider, they were rated with respect to significance (P1–P5; P1 and P2 needed a fix for go-live) and re-tested and closed when fixed and functioning.

- Local infrastructure deployment – The additional infrastructure required to implement MN-CMS included computers on wheels, desktop computers, electronic whiteboards, printers, scanners, barcode readers, etc. The purchase of these items had to follow the procurement process. Prior to the deployment of the hardware a WiFi connectivity survey was completed and the extra power points, data cables and ports required for the new hardware was installed in each unit. The procurement process for hardware was a multidisciplinary exercise involving IT, biomedical engineers, end users and infection control teams.26

- Training – 2500 staff across the four phase 1 sites benefited from training of 1–3 days’ duration depending on their system role. Course material was prepared, the train domain was populated and following a train the trainer program, training was provided to staff in each hospital by their peers. The trainers localized their training plans for their specific hospitals and kept detailed training records to ensure that all staff attended training.26 A small group of multidisciplinary staff were trained as trainers, they gave initial intense training to a larger group and superusers (available for the early weeks of go-live to support colleagues in each clinical area) and then provided the training for all staff with assistance from the superuser group.

- Go live – The go live phase involved setting up of user accounts, deployment of passwords, data migration and the manning of a 24x7 command center to support staff over the go live weekend and the post go live early life support (ELS) period. Each go live was supported on the ground by the members of the national project team, the vendor, team of engineers and solution specialists and the project managers and staff from the other sites.26 Data migration was undertaken for all patients close to term and for inpatients (women and babies) who were expected to remain for a period after go live. If delivered and documented on paper before go live, they remained on paper. Patients who attended in labor after the go live time had delivery documentation done on the EHR and completed their care on the EHR with appropriate agreed data documented including past history, allergies, medications, risk factors, etc. There was a ‘wash through’ period before all paper records were removed. The go live was a big bang, done over a weekend to allow phased introduction of the EHR to inpatient care, then outpatient care after the weekend.

- Medication management – EHRs and electronic medicines management offer potential to streamline patient care and to engineer safe medication use processes. Currently implemented clinical decision support functionality includes allergy checking, interaction checking, dose range checking, customized rules, weight-based dosing, prewritten order sentences and care plans. Electronic prescribing has been demonstrated to promote safe and effective prescribing practices and to reduce the risk of errors. The system facilitates clinical pharmacy services which have been demonstrated to improve patient outcomes and reduce the risk of serious patient harm.26

- Suggested key points for the implementation phase of an EHR

- Ensure multidisciplinary team (especially senior medical staff) involvement as early in the process as possible and tailor the involvement for each staff member

- Spend time developing the workstreams to ensure they cover the necessary aspects

- Limit the changes required to the system and control the changes required with a weekly meeting

- Go live: is when it will show what works and what can be improved

- Remember to keep the patient at the center of the project at all times

Optimization of a national system using MN-CMS as an example including the lessons learned and barriers experienced

- Risks and enhancements – The MN-CMS project team spent time developing the medication management element of the EHR, including clear order sentences with correct formulation dose, etc. Medication errors were highlighted early post go live as a key area that could be improved to enhance patient care. Enhancements such as the development of care plans and weight-adjusted dosing among others led to safer prescribing.

- Documentation – There are reductions in documentation time which should allow for better records. Staff do not have to duplicate records to the baby chart from the mothers and this saves time. All telephone consultations can be easily and clearly documented as part of the record. With ongoing optimization and training, staff can be assisted in the efficiency of their documentation.26

- Data quality – Routine data collection needs to be simple, clearly defined and an integral part of normal care and the responsibility of all healthcare staff. The need for high quality data was recognized early. Data quality personnel were put in place to check for data errors. Local information governance teams were set up to ensure the integrity of the data. The national project team also has an information governnance group to deal with issues at a national basis for a single national system.

- Reporting – The MN-CMS now has the capability of producing clinical reports for audit, research, financial and management requirements. These reports have taken time to build and test; however, they will be an invaluable data source in the future. The reporting function is highlighting data quality issues. Processes have been put in place; these include the employment of data quality staff, daily data quality checks that highlight where issues arose from these checks, staff are then contacted and requested to complete the data they have omitted. Ireland’s maternity service will have a high quality database contributed from normal care documentation to assess the quality of that care.26 Demographic information for all patients will be easily accessible and data that would not have been available before will now be available. Routine data collection needs to be simple, clearly defined and an integral part of normal care and the responsibility of all healthcare staff.

- Patient involvement – MyHealthPortal is to be a national online site designed for use by patients and their care givers. Its purpose is to engage patients in self-care and empower them to take a more active role in their healthcare management. This element of the MN-CMS project has not been set-up to-date. The aim is to have access for patients to the health portal in the near future. For the duration of their pregnancy women did have access to their paper medical charts. The MN-CMS board are committed to ensuring women have this access again.26 This element is key as internationally, there is a drive towards providing patient accessible EHRs (PAEHRs).28 However, there are limiting factors that include concerns about security and privacy, legal constraints and low uptake of other online resources for patients.17

- MN-CMS trainers are an invaluable support to the local project teams and to the end users on the ground. Since go live the four sites have engaged with their end users in optimization sessions where new, advanced and updated functionality has been taught. The training of new staff and locum doctors is carried out throughout the year.26

- Suggested key points for the optimization phase of an EHR

- Ensure optimization teams are in place before the project goes live

- Keep your go live trainers involved to increase the functionality and optimization of the chart

- Ensure an information governance structure is in place for all data requirements

- Ensure staff have mechanisms to feedback about the EHR: staff survey, feedback clinics

- Ensure patient access to their records via a patient portal

- Remember to keep the patient at the center of the project at all times

CONCLUSION

Globally the overall implementation of EHRs has not been as successful as it could of have been and the benefits of EHRs have not been seen yet. However, digital technologies have transformed banking, finance, transportation, navigation, internet search, retail, and now EHRs may bring the same revolutionary change to healthcare.29 This chapter highlights an EHR development as an example of a clinician led, patient focused, change management project. The project team ensured patient care was at the core of the development and implementation. The MN-CMS project is now entering phase 2 and this will allow for the project to be implemented across other sites. However, for the MN-CMS to continue to grow the initial four units are now in the ever evolving cycle of the optimization process to ensure the full benefit of the EHR for care. This task needs to be resourced adequately to allow the chart to really develop and to be used to its full potential. The everyday user needs to be engaged with to see how they are using the EHR, what they find easy and difficult to navigate, the staff are key to the optimization process. The staff are now the experts in using the system. The MN-CMS project team need to continue their excellent start to the roll-out of the MN-CMS. The Irish Department of Health need to continue to resource the EHR development. Ireland has the opportunity to slowly build an efficient, effective EHR that can impact on patient care from birth to death.

The information technology tools for EHRs are developing at incredible speed. Already the use of high-resolution cameras and ultrasound imaging can enhance the patient information in the record. The future for EHRs is fast approaching and new techniques may include vital signs automatically updating into the chart, an automated assistant that would listen to the interactions between doctor and patient and from verbal cues record the information in the exam room.29 Interactive patient portals will allow patients not only to review their data (ensuring accuracy), but also to input information prior to consultations and assist self-care as part of chronic disease management. Interoperability will mean the patient and their clinician will have full access irrespective of geography. As EHRs continue to progress, research will be required to examine how the medical profession have adapted to this introduction and how EHRs continue to influence the clinician–patient relationship. However, the greatest effect on healthcare will come from data science using the information available in the EHR. The potential of the data available in the EHR will make changes to all our lives if it is used correctly. Data protection and regulation laws need to be adhered to. The governance of data is key to the continued success of the development of the EHR. If any EHR project maintains that they keep the patient at the center of the project they need to ensure the patient data are used effectively. Patients need to be informed of how their data are used, why they are used in a particular way and how they can improve care and conditions for themselves and others. They also need to know their data are respected and entered correctly. Academic institutions have realized the importance of informatics and the importance of data retrieval and they are now providing modules at undergraduate level to prepare medical professionals.15 The potential value of data science is well recognized in the IT world; Vinod Khosla has suggested that “In the next 10 years data science will do more for medicine than all the biological sciences combined” It is likely that big data will assist us answer questions about the best care that would not be possible if we await the randomized trial approaches.

The change from paper to electronic records is a change project requiring a planned approach; seeing it as an IT project dooms it to failure. These projects need real commitment and leadership from the clinical community. We cannot continue to function in clinical care just replacing the written record with the computer, we need to look at our practice making the full use of the new tools provided in the era of the EHR. EHRs are central to modern medical care, supporting the organization and delivery of sustainable care and offering the potential for joint decision-making and involvement in self-care by the patient.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

Planning

- Engage key stakeholders early in the process.

- Strong leadership including clinical leadership is needed for decision-making.

- Take time for the procurement process.

- Set up a governance structure.

- Communicate with staff about the project and engage with interested parties.

- Remember to keep the patient at the center of the project at all times.

Implementation

- Ensure multidisciplinary team (especially senior medical staff) involvement as early in the process as possible and tailor the involvement for each staff member.

- Spend time developing the workstreams to ensure they cover the necessary aspects.

- Limit the changes required to the system and control the changes required with a weekly meeting.

- Go live: is when it will show what works and what can be improved.

- Remember to keep the patient at the center of the project at all times.

Optimization

- Ensure optimization teams are in place before the project goes live.

- Keep your go live trainers involved to increase the functionality and optimization of the chart.

- Ensure an information governance structure is in place for all data requirements.

- Ensure staff have mechanisms to feedback about the EHR: staff survey, feedback clinics.

- Ensure patient access to their records via a patient portal.

- Remember to keep the patient at the center of the project at all times.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Dr Mike Robson is the Clinical Director and Professor Richard Greene is the Obstetrics lead for the Maternal and Newborn Clinical Management System (MN-CMS) Project which is the design and implementation of an electronic health record (EHR) for all women and babies being cared for in maternity, newborn and gynecology services in Ireland. This chapter is based on the lessons learned from the design and implementation of the EHR and was not affected by their involvement with the project.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

REFERENCES

Robertson A, Cresswell K, Takian A, Petrakaki D, Crowe S, Cornford T, et al. Implementation and adoption of nationwide electronic health records in secondary care in England: qualitative analysis of interim results from a prospective national evaluation. BMJ 2010;341:c4564. | |

Campanella P, Lovato E, Marone C, Fallacara L, Mancuso A, Ricciardi W, et al. The impact of electronic health records on healthcare quality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Public Health 2016;26(1):60–4. | |

Menachemi N, Collum TH. Benefits and drawbacks of electronic health record systems. Risk Manag Healthc Policy 2011;4:47–55. | |

Roth CP, Lim Y-W, Pevnick JM, Asch SM, McGlynn EA. The Challenge of Measuring Quality of Care From the Electronic Health Record. American Journal of Medical Quality 2009;24(5):385–94. | |

Boonstra A, Versluis A, Vos JF. Implementing electronic health records in hospitals: a systematic literature review. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:370. | |

Health U. Differences Between EHR and EMR 2019 [Available from: https://www.usfhealthonline.com/resources/key-concepts/ehr-vs-emr/. | |

Frøen, J.F., Myhre, S.L., Frost, M.J. et al. eRegistries: Electronic registries for maternal and child health. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 16, 11 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-0801-7 | |

Consultant E. Glossary and Acronyms of EMR/EHR Terminology 2019 [Available from: http://www.emrconsultant.com/glossary-and-acronyms-of-emr-ehr-terminology/. | |

StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing 2018. https://www.statpearls.com/. | |

World Health Organization WH. eHealth at WHO 2018. https://www.who.int/ehealth/about/en/. | |

Gartner. IT Glossary. 2018. https://www.gartner.com/it-glossary/. | |

Mahoney M, S The History of Computing in the History of Technology. Annals of the History of Computing 10 1988:113–25. | |

Balestra M. Electronic Health Records: Patient Care and Ethical and Legal Implications for Nurse Practitioners. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners 2017;13(2):105–11. | |

Evans RS. Electronic Health Records: Then, Now, and in the Future. Yearb Med Inform 2016;Suppl 1:S48–61. | |

Burnel P. The introduction of electronic medical records in France: More progress during the second attempt. Health Policy 2018;122(9):937–40. | |

Hagglund M, Scandurra I. Patients' Online Access to Electronic Health Records: Current Status and Experiences from the Implementation in Sweden. Stud Health Technol Inform 2017;245:723–7. | |

Research AM. Electronic Health Records (EHR) Market by Product (Cloud-Based Software and Server-Based/On-Premise Software), Type (Inpatient EHR and Ambulatory EHR), Application (Clinical Application, Administrative Application, Reporting in Healthcare System, Healthcare Financing, and Clinical Research Application), and End User (Hospitals, Clinics, Specialty Centers, and Other End Users) – Global Opportunity Analysis and Industry Forecast, 2017–2023 2018 [Available from: https://www.alliedmarketresearch.com/electronic-health-records-EHR-market. | |

Nguyen L, Bellucci E, Nguyen LT. Electronic health records implementation: an evaluation of information system impact and contingency factors. Int J Med Inform 2014;83(11):779–96. | |

We are social website, Digital in 2018: World’s internet users pass the 4 billion mark 2018 [Available from: https://wearesocial.com/us/blog/2018/01/global-digital-report-2018. | |

Ross MK, Wei W, Ohno-Machado L. "Big data" and the electronic health record. Yearb Med inform 2014;9:97–104. | |

Doyle-Lindrud S. The evolution of the electronic health record. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2015;19(2):153–4. | |

Stone C. A Glimpse at EHR Implementation Around the World: The Lessons the US Can Learn. | |

Department of Health. eHealth Strategy for Ireland. 2013 http://www.ehealthireland.ie/Knowledge-Information-Plan/eHealth-Strategy-for-Ireland.pdf. | |

Ireland e. Maternal & Newborn Clinical Management System 2018 [Available from: http://www.ehealthireland.ie/MN-CMS. | |

MN-CMS Project Team, MN-CMS Phase I Closure Report Final, HSE. | |

Cerner. Women's Health 2018 [Available from: https://www.cerner.com/solutions/womens-health. | |

Wiljer D, Urowitz S, Apatu E, DeLenardo C, Eysenbach G, Harth T, et al. Patient accessible electronic health records: exploring recommendations for successful implementation strategies. J Med Internet Res 2008;10(4):e34. | |

Stanford Medicine, White Paper: The Future of Electronic Health Records, 2018, EHR Medical Symposium. http://med.stanford.edu/content/dam/sm/ehr/documents/EHR-White-Paper.pdf. | |

Frøen, J.F., Myhre, S.L., Frost, M.J. et al. eRegistries: Electronic registries for maternal and child health. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 16, 11 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-0801-7 |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards programme CLICK HERE)