This chapter should be cited as follows:

Lingman G, Borgfeldt C, Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.418543

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Gynecology Module

Volume 4

Benign gynecology

Volume Editor: Professor Shilpa Nambiar, Prince Court Medical Centre, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Chapter

Abnormal Uterine Bleeding

First published: June 2023

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

INTRODUCTION

The pattern of uterine bleeding during a woman's life has immense variation depending mainly on the endocrine situation. This varies during the adolescence, fertile period, perimenopausal, and postmenopausal periods. Mapping of the bleeding pattern is crucial to be able to separate normal from abnormal bleeding and for the understanding of the under-lying cause of the abnormal bleeding. Abnormal bleeding related to pregnancy is not included in this chapter.

Abnormal bleeding from the uterus is a significant cause of ill health, reduced quality of life and a common cause of contact with health care. The investigation includes determination of anemia, general and gynecological examination (speculum examination and bimanual palpation) as well as, if necessary, targeted sampling and transvaginal ultrasonography (TVS)

Causes of abnormal uterine bleeding may be classified as structural (Polyps, Adenomyosis, Leiomyoma and Malignancy, PALM) or non-structural (Coagulation Disorder, Ovulation Disorders, "Endometrial Associated", Iatrogenic Cause and "Not Otherwise Classified", COEIN).1 The classification system was endorsed by FIGO (The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics) in 2010.

Polyp | Coagulopathy |

Adenomyosis | Ovulatory dysfunction |

Leiomyoma | Endometrial |

Malignancy and hyperplasia | Iatrogenic |

Not otherwise classified |

First-line imaging method is by TVS, which plays a central role in the investigation of abnormal bleeding from the uterus. The TVS examination often needs to be supplemented with hydrosonography to visualize focal changes in the uterine cavity.

Hydrosonography provides a better diagnosis of intracavitary changes such as polyps or fibroids. Supplementation with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be used if the TVS diagnosis is unclear, for example, regarding adenomyosis, or for detailed mapping of fibroids prior to myoma nucleation or embolization.

Treatment of abnormal uterine bleeding may be pharmacological, surgical, or radiological (e.g., embolization) depending on the cause of the bleeding. With surgical treatment, minimally invasive surgery is favored. Many causes of abnormal uterine bleeding can be treated with hysteroscopic surgery, which can reduce the proportion of women undergoing hysterectomy.

DEFINITIONS

Normal menstrual bleeding occurs every 28th day from the first bleeding day to the first day of the next menstrual bleeding with a variation of about 7 days. It occurs when the ovulated egg is not fertilized.

Menorrhagia is defined as regularly occurring bleeding, often with 28 days intervals but more than 80 ml and causes anemia.

Metrorrhagia is the occurrence of irregular bleeding in between the normal bleeding.

1

Definition of normal menstruation and abnormal bleeding from the uterus.

Parameter | Normal | Abnormal | ||

Frequency | Absent (no periods or bleeding = amenorrhea | □ | ||

Rarely (>38 days) | □ | |||

Normal (≥24 to <38 days) | □ | |||

Frequent (<24 days) | □ | |||

Duration | Normal (≤8 days) | □ | ||

Extended/prolonged (>8 days) | □ | |||

Regularity | Normal (≤7–9 days) | □ | ||

Irregular (cycle variation ≥8–10 days) | □ | |||

Bleeding volume | Light | □ | ||

Normal | □ | |||

Heavy | □ | |||

Bleeding between cyclic periodic hemorrhages | None | □ | ||

Random | □ | |||

Cyclic (predictable) | Early cycle | □ | ||

Center cycle | □ | |||

Late cycle | □ | |||

Unscheduled bleeding on hormonal treatment (e.g., oral contraceptive pills, rings or patches) | Not applicable (not on hormonal treatment) | □ | ||

None (on hormonal treatment) | □ | |||

Yes, occurs | □ | |||

ETIOLOGY, DIAGNOSTIC APPROACHES, AND TREATMENT

Polyps (PALM-P)

Uterine polyps are mostly noncancerous (benign) but may cause bleeding. Diagnosis is revealed with TVS and hydrosonography.2 Rarely, precancerous changes of the uterus (endometrial hyperplasia) or uterine cancers (endometrial carcinomas) appear as uterine polyps.3 If vaginal bleeding occurs, removal of the polyp with hysteroscopy and a tissue analysis with histopathology evaluation is recommended.

Adenomyosis (PALM-A)

Adenomyosis is a special form of endometriosis with the growth of endometrial mucosa in the myometrium. Women with adenomyosis often have abnormal uterine bleeding (heavy menstruation), pain during menstruation or intercourse and a history of infertility. The prevalence of adenomyosis in the female population is not exactly known but a TVS study has found a prevalence increased with age up to 30% above 40 years of age.4

TVS is recommended as the first-line imaging method, but MRI can be used.5 There is no pharmacological treatment specifically designed to treat adenomyosis. When choosing treatment, an individual assessment must be made and based on the woman's age, fertility wishes and symptoms. The pharmacological treatment is symptomatic and aims to make the patient amenorrheic (bleeding-free) and reduce pain, i.e., hormonal IUD, gestagens, combined oral contraceptives.6 Hysterectomy is the definitive treatment option.

Leiomyoma (PALM-L)

Leiomyomas (uterine fibroids) are benign very common tumors in the uterine myometrium. Between the ages of 30 and 40, it is found in one out of ten women and between the ages of 40–50, every fourth woman has a leiomyoma. These can intrude into the uterine cavity, alter the endometrium, and cause mainly menorrhagia, sometimes causing severe anemia. They are benign but can grow fast, then difficult to separate from the malignant type – leiomyosarcomas. Some myomas behave like polyps and are then expelled by the uterus, and myoma births can be seen. TVS reveals the diagnosis. There are various treatment modalities, from hormonal treatment (gestagens, GnRH analogs, or selective gestagen modulators),7 tranexamic acid to surgery via laparoscopy or open surgery with either myomectomy or hysterectomy.8 Hysteroscopic myomectomy or arterial embolization to shrink the leiomyomas are also alternatives.9 Asymptomatic leiomyomas do not need to be followed-up.10

Malignancy or endometrial hyperplasia (PALM-M)

Endometrial hyperplasia is divided into hyperplasia with and without atypia.11

The treatment of hyperplasia is individualized depending on the presence of atypia and other risk factors.

Endometrial hyperplasia is defined histologically as an abnormal growth of the endometrial glandular tissue. In pre-menopausal women, this usually occurs when there is irregular or absence of ovulation, e.g., in polycystic ovary syndrome. In postmenopausal women, hyperplasia can develop at high estrogen levels, e.g., in the case of estrogen-only substitution or in the case of obesity.12

The diagnosis is found through endometrial biopsy with histo-pathological confirmation.

The treatment of endometrial hyperplasia without atypia is continuous gestagen treatment or a gestagen containing intra-uterine device.13

In patients with atypical hyperplasia the risk of concomitant endometrial cancer is high (one out of three patients), which is why the main recommendation is hysterectomy. In women of older age with pre-existing comorbidity, where a surgical procedure may be risky, conservative treatment with gestagens combined with regular clinical examination including endometrial biopsies may be considered. In a younger woman with fertility desires, progestogen treatment may be considered combined with regular clinical examinations including targeted hysteroscopic sampling from the endometrium.

Endometrial cancer

Endometrial cancer is rare in the premenopausal women but must be ruled out in all postmenopausal women if there is vaginal bleeding. Patients with obesity are at an increased risk of endometrial neoplasia regardless of age. Patients with obesity have high levels of endogenous estrogen due to the conversion of androgens to estradiol in adipose tissue. This becomes a source of endogenous unopposed estrogen in the setting of ovulatory dysfunction. In postmenopausal women with vaginal bleeding, the woman consults the physician early and the diagnosis is confirmed with an endometrial biopsy. The endometrial sampling is easily performed as an office biopsy, but dilation and curettage or hysteroscopically directed biopsy may be performed if bleeding persists after a normal endometrial biopsy. Most endometrial cancer patients are found and treated with surgery including removal of the uterus (hysterectomy), ovaries and tubes plus minus lymph nodes. In an advanced stage with lymphatic or other spread, chemoradiation may be added.

Leiomyosarcoma

Leiomyosarcomas are very rare tumors in the uterine muscle wall. It is mostly discovered when the histo-pathology is analyzed after hysterectomy due to heavy bleeding or abdominal pain with a presumed myoma indication.

Cervical cancer

This form of cancer is diminishing due to human papilloma virus (HPV) vaccination and screening programs. HPV is the agent and found in more than 99% of the cervical cancer cases. In societies with no HPV vaccination or no organized screening program cervical cancer is common. Women on immunosuppression or women with untreated HIV infection are at high risk for HPV infections. Most common are the squamous cell cancer (75%) and adenocarcinoma (23%). The trend in detection of this cancer form is to detect the genital HPV via vaginal self-sampling or cervical smear to be able to find and treat pre-carcinogenous lesions. Metrorrhagia, spotting, and postcoital contact bleeding are the main symptom in early-stage cancer. The treatment in early-stage cancer is surgery, consisting of conization of the uterine cervix to remove the cancer or radical hysterectomy. Other fertility sparing options include radical trachelectomy. If the cancer is in a late stage the symptoms often are pelvic pain or hydronephrosis due to obstructions of the ureters. The treatment is then radio-chemotherapy.

Coagulopathy/bleeding disorders (COEIN-C)

Among women (regardless of age) with heavy menstrual bleeding, there is a coagulation disorder in 20%. FIGO recommends screening to detect coagulation disorders in women with abnormal uterine bleeding.14 Women with impaired ability to coagulate and form blood clots may suffer from menorrhagia.15 Women with predisposition to hemophilia may have reduced levels of von Willebrands factor, FVIII/FIX levels at the level of mild hemophilia. This can lead to a generally increased tendency to bleed as well as heavy menstruation and bleeding and complications after childbirth. The treatment is tranexamic acid and/or oral contraceptive or gestagen IUD.16

Ovulation disorders (COEIN-O)

Ovulation disorders include a spectrum of abnormalities with varying bleeding patterns.

A deviating bleeding pattern can be explained by, e.g., thyroid disorder, missed ovulation (anovulatory hemorrhage), functional hypothalamic amenorrhea, polycystic ovary syndrome, premature ovarian insufficiency, hyperprolactinemia, and pituitary tumors.17

The investigation should include analysis of TSH and prolactin and depending on which diagnosis is suspected, e.g., FSH, LH, 17-hydroxyprogesterone, testosterone, SHBG, androstenedione, DHEAS, and estradiol.17

Treatment of ovulation disorders is governed by the patient's age, fertility requirements, degree of bleeding disorder, need for contraception, and other medical factors. In the case of thyroid dysfunction or elevated prolactin levels, these conditions should be treated. In the event of a persistent bleeding disorder, this must be investigated further, and other causes of the bleeding disorder excluded.

PCOS

Polycystic ovary syndrome, or PCOS, is the most common endocrine disorder in women of reproductive age. The syndrome is named after the characteristic multiple small follicular cysts seen on ultrasound close to the ovarian surface, although it is important to note that this is a sign and not the underlying cause of the disorder.

PCOS often causes irregular menstrual periods (oligomenorrhea), heavy periods, excessive generalized hair growth, acne, pelvic pain, difficulties getting pregnant. The primary characteristics of this syndrome include hyperandrogenism, anovulation, insulin resistance. The treatment is oral contraceptives or if desire for pregnancy fertility stimulation.18 Metformin and other insulin sensitizing agents have also been used with some success at reducing androgen levels and restoring ovulatory cycles with weight loss.

Premature ovarian insufficiency

In women <40 years, amenorrhea and hypergonadotropic hypogonadism, premature ovarian insufficiency is present. To reduce vasomotor symptoms and prevent osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease, these patients should be treated with hormone therapy.

The treatment can be conventional MHT or combined contraceptive pills containing both estrogen and progestogen depending on age and need for contraception.19 Contraindications are only ongoing VTE, current arterial vascular disease or breast cancer. Previous venous thromboembolism is not an absolute contraindication, but transdermal treatment is recommended.

Functional hypothalamic amenorrhea

Functional hypothalamic amenorrhea is a condition of chronic anovulation. The condition can be explained by, for example, excessive exercise, weight loss or stress.20 After lifestyle changes, GnRH pulsatility and LH peak return and thus ovulation and menstruation.

Treatment aims both to restore a possible excessive exercise pattern, stress management and to normalize food intake. This treatment is based on psychological support and, if necessary, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).

If contraception is needed, combined methods containing both estrogen and progestogen are recommended due to the need for estrogen supplements. If there is no need for contraception, MHT treatment containing both estrogen and progestin can be initiated. In long-term amenorrhea, bone density measurement may be indicated due to the risk of osteoporosis due to estrogen deficiency. In the case of verified osteoporosis, the osteoporosis treatment is initiated.

Endometrial-associated causes (COEIN-E)

Primary cause of bleeding is in the endometrium, but structural changes, such as polyp, hyperplasia, and malignancy have been ruled out.

Endometrial destruction or endometrial resection may be a treatment option.

In the case of abnormal bleeding from the uterus in women with a structurally normal uterus and uterine cavity where coagulation disorder and ovulation disorder are excluded, the primary cause may be in the endometrium, e.g., abnormal hemostasis, inflammation, or infection.21 These variants of endometrial dysfunction are poorly researched, lack reliable diagnostic methods, and are exclusionary diagnoses.

Infections

Infections, like cervicitis, endometritis, and salpingitis can cause regular, menstrual-rich bleeding, but sometimes also metrorrhagia. The symptoms are often lower abdominal pain and fever with the intensity level often related to the severity of the infection. This includes a spectrum ranging from light cervicitis, endometritis, to salpingitis and peritonitis. The latter are severe and sometimes life-threatening infections. This is however, rare as the uterine tubes often lock and stop the infection and formation of tubo-ovarian abscesses. An IUD can increase the risk of those infections due to facilitating of bacterial spreading along the device up into the uterine cavity and tubes. The infection agents are mainly E. coli, Chlamydia and gonococcus. Diagnosis is found via PCR analysis or bacterial culture. The treatment is antibiotic therapy targeted at the organisms detected on culture studies.

Treatment of COEIN-E

Treatment may be individualized based on the cause. Infection is treated based on the agent. Pharmacological treatment can be tried with NSAIDs, tranexamic acid, and hormonal methods as above. Endometrial destruction or endometrial resection may be an alternative in the case of troublesome bleeding to reduce the amount of heavy bleeding. Structural changes should have been ruled out and there should be no clinical signs of infection or inflammation.

Prior to endometrial destruction, samples should be taken from the lining of the uterus to rule out hyperplasia or malignancy.22 Before endometrial destruction is performed, progestogen treatment with, e.g., medroxyprogesterone 10 mg daily for 10 days is given to achieve a thinner endometrium and thus have a better treatment effect. Contraindications to the procedure are ongoing pregnancy, endometrial hyperplasia, malignancy in the endometrium, desire for pregnancy, ongoing infection locally and intrauterine inserts. Relative contraindications are previous uterine surgery, especially myomectomy or > 3 previous cesarean sections, as the uterine wall may be thinner in these situations.

Iatrogenic (COEIN-I)

Medications can cause altered bleeding patterns. Modification of the medication that caused the bleeding disorder should be done in consultation with the treating physician.

Under this heading are all iatrogenic factors that can affect the bleeding pattern, e.g., treatment with female sex hormones, anticoagulants, antidepressants, antipsychotics, tamoxifen, and IUDs.14

In treatment with female sex hormones, irregular bleeding is common. The reason may be temporarily lowered hormone levels due to a forgotten tablet, too long a tablet interval, or the use of drugs that lower the hormone level due to increased liver metabolism. Long-term use of progestogens can also cause abnormal bleeding due to atrophy of the endometrium.

Treatment with anticoagulants can cause abnormal uterine bleeding in menstruating women with both an increase in the number of bleeding days and the amount of bleeding as well as postmenopausal bleeding.

Some antidepressants, e.g., tricyclic antidepressants, and antipsychotics can affect dopamine metabolism and result in elevated prolactin levels and thus anovulation. Other drugs such as GnRH analogs, Tamoxifen, and aromatase inhibitors can also cause abnormal bleeding from the uterus.

Treatment

Changes in the medication of non-gynecological diseases must be discussed with the doctor responsible for the medication. In some cases, switching to another preparation or changing the dose may improve the symptoms.

Not otherwise classified (COEIN-N)

The "not otherwise classified" group includes unusual causes of abnormal uterine bleeding.

Acquired arteriovenous malformations most often occur during pregnancy or after surgery on the uterus.

Most pregnancy-related arteriovenous malformations can be treated conservatively or with evacuation of pregnancy remnants. In the event of heavy bleeding that may be difficult to treat, embolization may become relevant.23

A so-called isthmocele (defect in the uterine wall after a cesarean section) can cause prolonged spotting after menstruation. Isthmocele can cause prolonged spotting after menstruation. These are explained by the fact that blood collects in the defect in the uterine wall.24 Surgical treatment of the uterine defect and hysterectomy is recommended.

The term "not otherwise classified" includes causes that are poorly defined, insufficiently investigated or are very unusual.

DIAGNOSIS

History

Questions

What is the main problem? Is the woman worried about the bleeding?

Irregular or regular bleeding? Quantify the bleeding. How often does the woman need to change pads? Does she bleed through the pads? How is the bleeding related to her menstruation?

Has the bleeding pattern changed last 3–6 months?

Sexual history:

- What kind of contraception does the woman use?

- Does she have a new partner?

- Does she bleed after coitus?

Examination

Pregnancy must be excluded or confirmed.

Vaginal speculum examination:

Is there any vaginal atrophy, discharge, cervical lesions, i.e., polyps, suspicion of cancer?

Bimanual palpation:

Is there any enlargement of the uterus with myoma or adnexal tumors?

Transvaginal or abdominal ultrasonography:

Endometrial thickness? Polyps? Leiomyoma? Intra-uterine device in the right place? Adnexal tumors or ovarian cysts?

If endometrial enlargement hydrosonography may be indicated to visualize polyps or intracavitary leiomyoma.

Further examinations when indicated:

Blood samples

Hemoglobin

- Pregnancy test (if not already performed)

- Complete blood count with platelets and examination of the peripheral blood smear and ferritin to detect anemia, iron deficiency without anemia,51 or thrombocytopenia

- Coagulation panel (activated partial thromboplastin time [aPTT]/partial thromboplastin time [PTT], prothrombin time [PT], and fibrinogen)

The evaluation generally also includes a von Willebrand panel

- Plasma von Willebrand factor (VWF) antigen

- Plasma VWF activity (ristocetin cofactor activity)

- Factor VIII activity

Measurement of hormones:

- thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) Hypo or hyperthyroidism

- prolactin Prolactinoma

- testosterone, sexual hormone binding globulin (SHBG), FSH, LH, Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS)

Screening for STIs if indicated by sexual/reproductive history

MANAGEMENT

The primary etiology should be treated, if possible. This includes endocrine or infectious disorders that are treated medically (e.g., polycystic ovarian syndrome or endometritis/cervicitis), structural lesions that are resectable via hysteroscopy (endometrial polyp, submucosal fibroid) as well as appropriate gynecological cancer treatment.

The initial approach in patients with chronic bleeding disturbances is usually pharmacologic treatment. The choice of medication depends upon the factors listed above.

Secondary approaches are used for patients who fail or cannot tolerate medical therapy or who prefer treatment options that do not require frequent dosing. Primary deciding factors are whether the patient is planning future childbearing and the level of invasiveness and risk associated with the procedure.

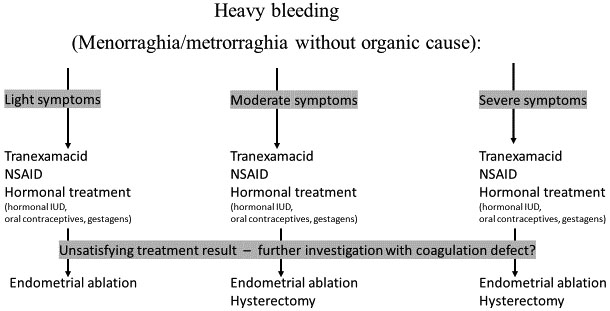

Heavy menstruation (menorrhagia)

If no organic reason is found the treatment is meant to reduce the symptoms, tranexamic acid (an anti-fibrinolytic drug) is used to treat or prevent excessive blood loss from heavy menstruation and reduces the lost blood with 30–55%. It is taken either orally (1 g 3–4 times a day during bleeding) or by injection into a vein. Side effects are rare.

If the copper-IUD is used, then changing to other contraceptive methods is recommended, i.e., gestagen containing IUD (Mirena).

Combined oral contraceptives (eostrogen+gestagens) reduces the bleeding with 45–88%. These are recommended to be used without pause, which minimize the periods and risk for anemia.

Hysteroscopic resections of polyps or myoma eliminate these organic reasons. Hysteroscopic resection of the whole endometrium or thermal ablation of the uterine cavity are effective ways of reducing bleeding after childbearing age. These procedures may be performed at the outpatient policlinic with local anesthetics.

If these methods do not work minimal invasive hysterectomy may be necessary to eliminate the bleeding problem.

Irregular bleeding (metrorrhagia)

Hormonal disturbances should be evaluated. If suspicious of anovulatory bleeding, which is common at menarche or pre-menopause medical treatment with cyclic gestagen should be initiated. Gestagen (i.e., medroxyprogesteronacetate 10 mg x1 during 10–12 days (cycle day 15–25) during 3–6 months).

If the bleeding disturbances start at menarche combined oral contraceptives may be used.

IUD with gestagen may also reduce the irregular bleeding (Figure 1).

1

Evaluation and treatment in women with heavy bleeding without organic cause.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- For diagnosis TVS and hysteroscopy is helpful. Gestagens or hysterectomy are treatments depending on cause.

- TVS is used followed by biopsy for diagnosis, Endometrial hyperplasia with atypias and all other malignancies are treated with hysterectomy.

- The suspicion of functional reasons for bleeding disorders should be investigated focused upon coagulation disorders, hormonal broad blood examinations.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) of this chapter declare that they have no interests that conflict with the contents of the chapter.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

REFERENCES

Munro MG, Critchley HO, Broder MS, et al. FIGO classification system (PALM-COEIN) for causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in nongravid women of reproductive age. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2011;113(1):3–13. | |

Khafaga A, Goldstein SR. Abnormal Uterine Bleeding. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2019;46(4):595–605. | |

van Hanegem N, Breijer MC, Slockers SA, et al. Diagnostic workup for postmenopausal bleeding: a randomised controlled trial. BJOG 2017;124(2):231–40. | |

Naftalin J, Hoo W, Pateman K, et al. How common is adenomyosis? A prospective study of prevalence using transvaginal ultrasound in a gynaecology clinic. Hum Reprod 2012;27(12):3432–9. | |

Tellum T, Nygaard S, Lieng M. Noninvasive Diagnosis of Adenomyosis: A Structured Review and Meta-analysis of Diagnostic Accuracy in Imaging. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2020;27(2):408–18 e3. | |

Struble J, Reid S, Bedaiwy MA. Adenomyosis: A Clinical Review of a Challenging Gynecologic Condition. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2016;23(2):164–85. | |

Hartmann KE, Velez Edwards DR, Savitz DA, et al. Prospective Cohort Study of Uterine Fibroids and Miscarriage Risk. Am J Epidemiol 2017;186(10):1140–8. | |

Bhave Chittawar P, Franik S, Pouwer AW, et al. Minimally invasive surgical techniques versus open myomectomy for uterine fibroids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014(10):CD004638. | |

Gupta JK, Sinha A, Lumsden MA, et al. Uterine artery embolization for symptomatic uterine fibroids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014(12):CD005073. | |

De La Cruz MS, Buchanan EM. Uterine Fibroids: Diagnosis and Treatment. Am Fam Physician 2017;95(2):100–7. | |

Emons G, Beckmann MW, Schmidt D, et al. New WHO Classification of Endometrial Hyperplasias. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd 2015;75(2):135–6. | |

Armstrong AJ, Hurd WW, Elguero S, et al. Diagnosis and management of endometrial hyperplasia. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2012;19(5):562–71. | |

Mittermeier T, Farrant C, Wise MR. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system for endometrial hyperplasia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020;9:CD012658. | |

Munro MG, Critchley HOD, Fraser IS, et al. The two FIGO systems for normal and abnormal uterine bleeding symptoms and classification of causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in the reproductive years: 2018 revisions. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2018;143(3):393–408. | |

Kouides PA, Conard J, Peyvandi F, et al. Hemostasis and menstruation: appropriate investigation for underlying disorders of hemostasis in women with excessive menstrual bleeding. Fertil Steril 2005;84(5):1345–51. | |

Kadir RA, Lukes AS, Kouides PA, et al. Management of excessive menstrual bleeding in women with hemostatic disorders. Fertil Steril 2005;84(5):1352–9. | |

Hale GE, Robertson DM, Burger HG. The perimenopausal woman: endocrinology and management. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2014;142:121–31. | |

Teede HJ, Misso ML, Costello MF, et al. Recommendations from the international evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2018;89(3):251–68. | |

Michala L, Stefanaki K, Loutradis D. Premature ovarian insufficiency in adolescence: a chance for early diagnosis? Hormones (Athens) 2020;19(3):277–83. | |

Gordon CM, Ackerman KE, Berga SL, et al. Functional Hypothalamic Amenorrhea: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2017;102(5):1413–39. | |

Wouk N, Helton M. Abnormal Uterine Bleeding in Premenopausal Women. Am Fam Physician 2019;99(7):435–43. | |

Leathersich SJ, McGurgan PM. Endometrial resection and global ablation in the normal uterus. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2018;46:84–98. | |

Szpera-Gozdziewicz A, Gruca-Stryjak K, Breborowicz GH, et al. Uterine arteriovenous malformation – diagnosis and management. Ginekol Pol 2018;89(5):276–9. | |

Kremer TG, Ghiorzi IB, Dibi RP. Isthmocele: an overview of diagnosis and treatment. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992) 2019;65(5):714–21. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards programme CLICK HERE)