This chapter should be cited as follows:

Malhotra N, Sinha P, et al., Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.418233

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Gynecology Module

Volume 4

Benign gynecology

Volume Editor: Professor Shilpa Nambiar, Prince Court Medical Centre, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Chapter

Pudendal Neuralgia

First published: June 2023

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

OBJECTIVES

- Identify the etiology of pudendal nerve entrapment syndrome.

- Review the evaluation of pudendal nerve entrapment syndrome.

- Outline the management options available for pudendal nerve entrapment syndrome.

- Stress on interprofessional team strategies for improving care, coordination and communication and improve outcomes.

INTRODUCTION

Pudendal neuralgia is a severely painful and disabling neuropathic condition, affecting both men and women, involving the dermatome of the pudendal nerve first described in 1987 by Amarenco et al.1 It is also known as Alcock’s canal syndrome,2 cyclist syndrome, and pudendal nerve entrapment.3

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Its prevalence is estimated to be about 1/100,000 people, affecting females more than males.4 Research states that pudendal neuralgia is diagnosed in 4% of patients taking treatment for chronic pelvic pain.

ETIOPATHOGENESIS

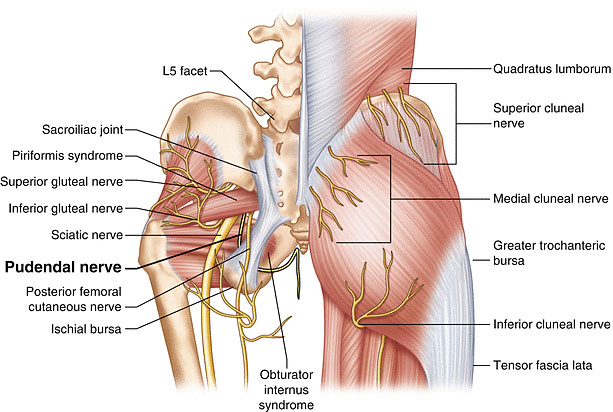

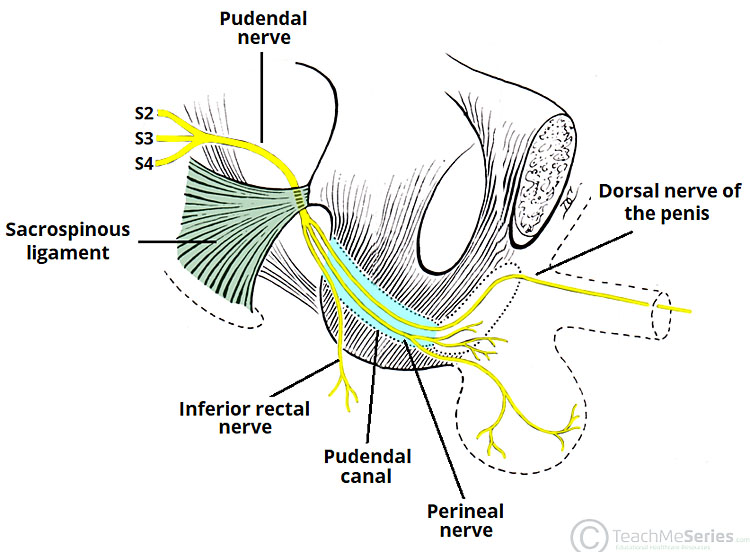

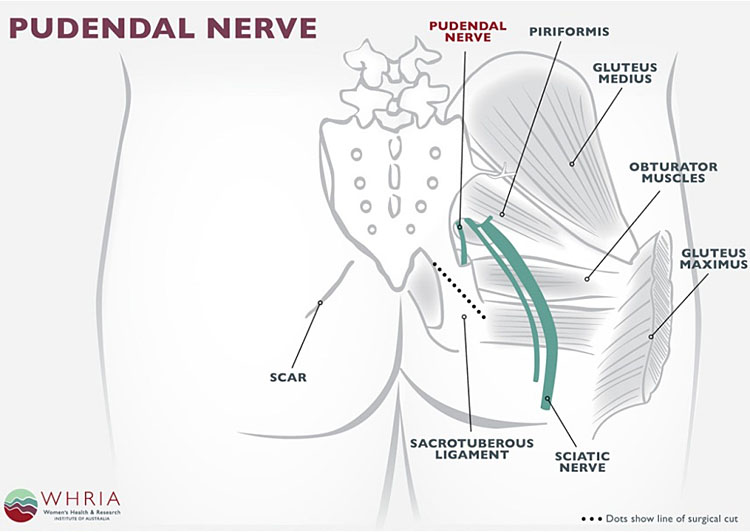

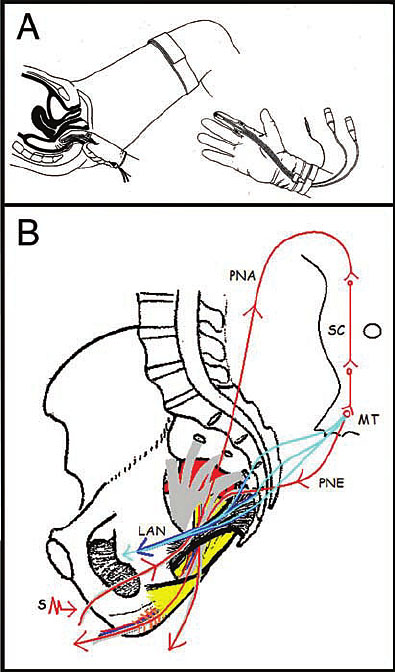

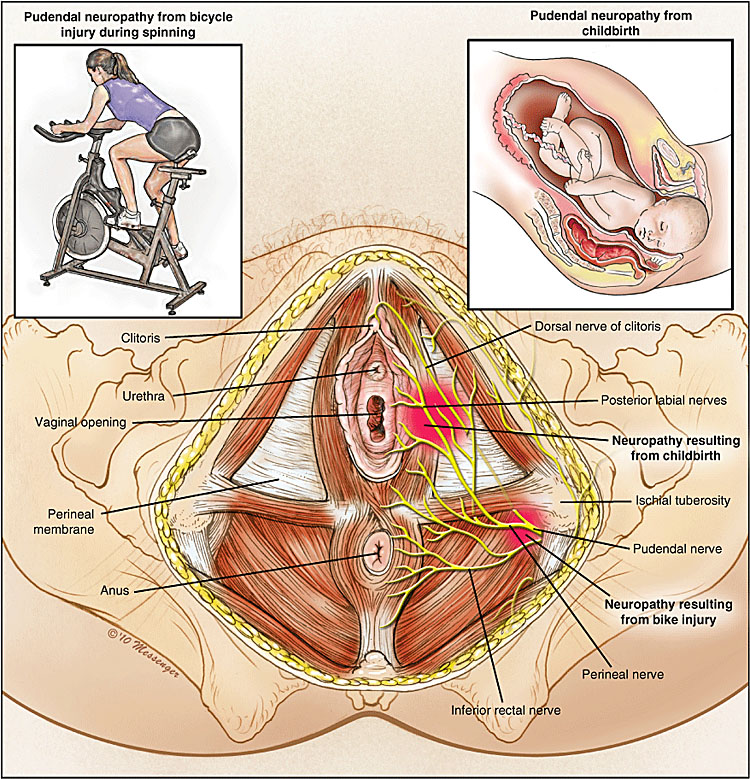

Pudendal neuralgia is a functional entrapment where pain occurs during a compression or stretch maneuver. The exact mechanism of nerve dysfunction and damage is dependent on its etiology. Caused by compression, stretch, direct trauma, and radiation. The neuropathy worsens due to repetitive micro-trauma resulting in persistent pain and dysfunctional complaints. The pudendal nerve is compressed during prolonged sitting and cycling.5 Stretch of the nerve by straining with constipation and childbirth can cause pudendal neuropathy. Fitness exercises, machines, weight lifting with squats, leg presses or karate with kickboxing and rollerblading are all etiologic factors. Figures 1(a,b) show the anatomy and path of the pudendal nerve and how it can get entrapped (Figure 2).

1a

Pudendal nerve entrapment.

1b

Pudendal nerve anatomy.

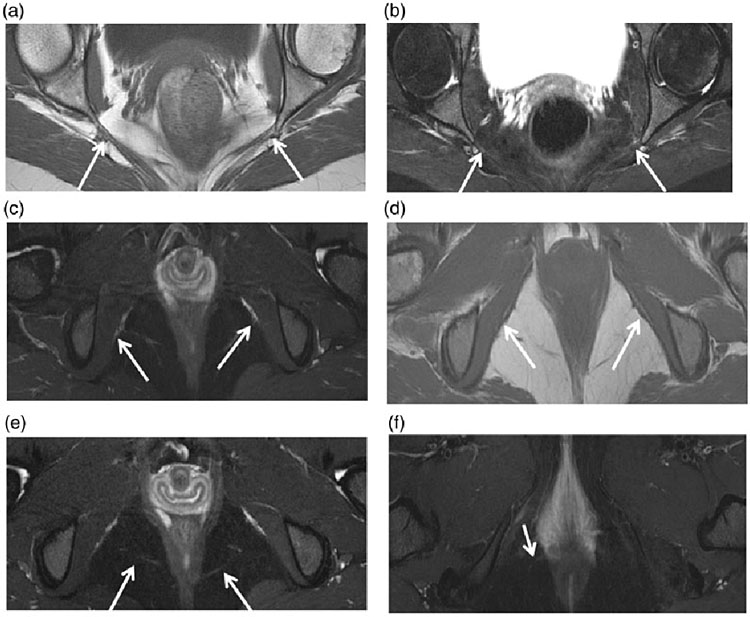

2

Pudendal diffusion tensor imaging. The arrows show how the pudendal nerve can be entrapped.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Pain may be localized to the clitoris, labia, vagina, and vulva in women, and to the penis and scrotum in men, excluding testes. In both sexes, pain may be localized to the perineum, rectum, and area immediately medial and anterior to ischial tuberosities.

Symptoms are frequently unilateral, however, in patients presenting with bilateral pain, there is often a more affected side. Neuropathic pain is described as a burning, tingling, or itching sensation.6 Patients have significant hyperalgesia (increased sensitivity to mild painful stimuli), allodynia (pain in response to nonpainful stimuli), and paraesthesia (sensation of tingling or numbness). A small percentage of patients may have pain outside the area of innervations for the pudendal nerve, commonly presenting in the lower abdomen, posterior thigh, and lower back. This pain is usually attributed to muscle spasm or somatic referred pain.

Typically, symptoms are present in sitting position and absent during standing or lying down. However, with disease progression, the pain may become constant and severely aggravated by sitting. Most patients tolerate sitting for only several minutes before their pain becomes unbearable, and some are unable to sit at all. Interestingly, most patients report absence or improvement of pain when sitting on a toilet seat, as the body weight in this position is supported by the ischial tuberosities, thereby relieving pressure from the pelvic floor.7 Similarly, sitting on hard surfaces is more comfortable as well. Another common symptom is the sensation of a foreign body in the vagina, perineum or rectum, frequently described as a “golf ball” or “tennis ball”. To help describe this sensation, the term “allotriesthesia” has been coined from the Greek allotri- (foreign) and esthesia (sensation). Defecation and urination can also be painful, leading to dyschezia and urinary hesitancy. Urinary or fecal incontinence may develop from decreased sphincter tone if motor function is affected.8 Patients with pudendal neuralgia are often diagnosed with interstitial cystitis,9 vulvodynia, dyspareunia, and persistent sexual arousal. Dyspareunia, pain with intercourse, can be so severe that patients are often unable to engage in sexual activity. Pain may be specific to arousal/erection, ejaculation, vaginal penetration, as well as orgasm. In contrast, pudendal neuralgia may also present as persistent sexual arousal, also called restless genital syndrome.10 It is a very unpleasant and sometimes painful sensation of intense arousal without the ability to climax. Unfortunately, this sensation remains constant, climax itself providing only momentary relief.

DIAGNOSIS

Its diagnosis heavily relies on history and physical examination. History should first be directed at identifying symptoms of pudendal neuralgia followed by an inciting event. Commonly, surgery, vaginal delivery, or pelvic trauma is identified. Pudendal nerve entrapment is rarely idiopathic. Physical examination should confirm that pain is in the dermatome of the pudendal nerve.11 Sensation over this area may be assessed, although most patients will not have sensory defects. Skin perspiration or dryness is frequently identified on the affected side. A detailed examination of the back, abdomen, and pelvic floor muscles should be performed. The rectus abdominis, psoas major, levator ani, obturator internus, and coccygeus muscles are assessed for tenderness, strength, and spasm. Also, tenderness over the ischial spines and Alcock’s canal is consistent with pain originating from the pudendal nerve. Palpation of this area precipitates a tingling sensation commonly known as Tinel’s sign. Tinel’s sign may also be present when percussing the dorsal clitoral/penile branch as it emerges from underneath the inferior ramus of the pubic bone. Even after a detailed examination, it may be difficult to distinguish whether tenderness is caused by nerve injury or muscle spasm. In these cases, nerve blocks or Botox injections into the pelvic floor muscles may aid in the diagnosis of pudendal neuralgia.

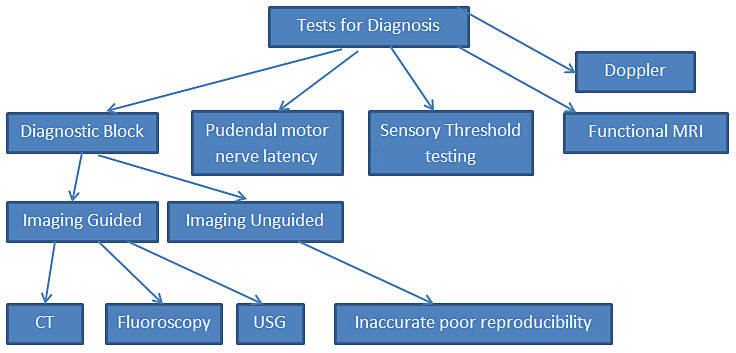

Professor Roger Robert from Nantes, France, published his own criteria to diagnose pudendal neuralgia in 2008 (Table 1). These criteria have been validated12 and are based on the consensus of mostly European physicians with extensive experience treating pudendal neuralgia. The study showed that patients meeting all the required criteria have better outcomes from decompression surgery than patients who only partially meet them. Figure 3 shows tests of algorithm for diagnosis.

1

Nantes criteria for the diagnosis of pudendal neuralgia.

Inclusion criteria

|

Exclusion criteria

|

Complementary criteria

|

Associated signs (Figures 3 and 4 show pudendal nerve pain areas)

|

3

Test algorithm.

4

Pudendal nerve pain areas. MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; CT, computed tomography; PNMTL, perineal branch of the posterior femoral cutaneous nerve.

Tests used for diagnosing pudendal neuralgia include the following: diagnostic blocks of the pudendal nerve(s), pudendal nerve motor terminal latency, sensory threshold testing, Doppler ultrasound, and functional MRI.

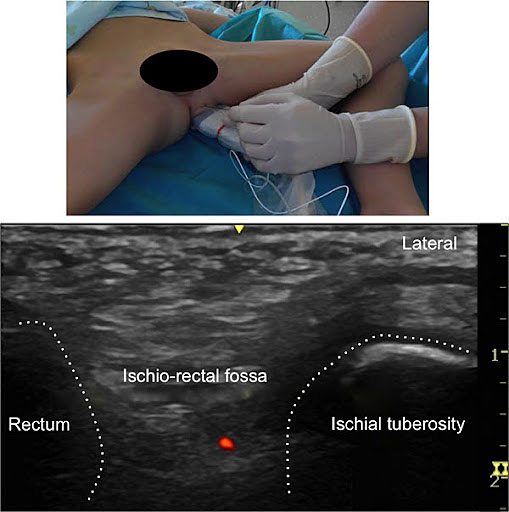

Diagnostic pudendal nerve blocks are important Nantes inclusion criteria. These blocks can be performed unguided or with the use of image-guided techniques. Resolution of pain after the block, even if temporary, supports the diagnosis of pudendal neuralgia. These blocks also serve a very important therapeutic role, which will be described in the treatment section (Figures 5 and 6).

5

Transperineal pudendal nerve block.

6

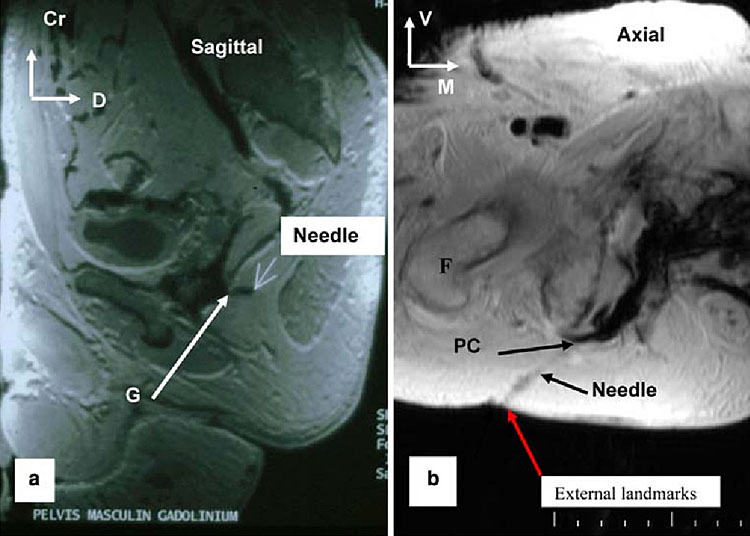

Transgluteal pudendal nerve block. (a) Sagittal view; (b) axial view.

Unguided pudendal nerve blocks result in their inaccuracy and poor reproducibility. Failure of the procedure to alleviate pain may be due to operator error and not necessarily due to the absence of pudendal neuralgia. As a result, image-guided blocks are preferred to support or rule out the diagnosis. Image-guided pudendal nerve blocks may be performed under fluoroscopy, ultrasound, or CT scan. The first two are advantageous as they may be performed in the office setting, whereas CT scan requires a hospital or radiological facility. Injections under fluoroscopic guidance are performed with the patient in the prone position.13 A radiopaque needle is placed directly through the buttock and aimed toward the ischial spine. The injection is placed slightly medially and inferior to the ischial spine, similar to the transvaginal injection. Ultrasound-guided injections can be performed transvaginally or transgluteally.14 The pudendal vessels are identified via Doppler imaging and the injection is placed immediately posterior to the vessels, in the area of the pudendal nerve. Blocks under CT guidance are performed transgluteally with the patient in the prone position.15 The advantage of CT-guided injection is that it allows placement of the block into Alcock’s canal. Placing blocks into Alcock’s canal allows differentiation between pudendal neuralgia and inferior cluneal neuralgia. With properly performed blocks, patients may have relief of pain for hours to weeks. Longer efficacy can be achieved with steroid medications injected together with local anesthetics. The most commonly injected steroid is Triamcinolone 40 mg per side. The addition of steroids decreases inflammation around the nerve, which may lead to improvement in pain.16 It has also been shown that steroids cause muscle atrophy leading to decreased pressure on the nerve. This steroid effect begins approximately 2 weeks from injection and may last from weeks to months.17

Pudendal nerve motor terminal latency (PNMTL) (Figure 7)

7

Pudendal nerve motor terminal latency.

It measures conduction velocity of electrical impulses through the pudendal nerve.16,17 Electrical impulses are applied transvaginally or transrectally at the level of the ischial spine and the time needed for the impulse to travel to the perineal muscles is measured. Unfortunately PNMTL values in patients with previous vaginal delivery or pelvic surgery are highly variable due to pelvic floor muscle stretching.18,19 Also, PNMTL measurements have very high intra- and interobserver variability.20 Thus, the PNMTL is considered by most experts to be too inconsistent for the diagnosis of pudendal neuralgia. More accurate tests, in which the return electrode needle is placed directly into the transverseperineal muscle, have been developed. However, their accuracy regarding diagnosis of pudendal nerve entrapment is still under investigation.

Quantitative sensory threshold testing is an important concept in diagnosing peripheral nerve injury.21 The premise of this test is that compressed nerves lose the ability to transmit sensation of temperature changes and vibration. The most commonly used test is the warm detection threshold test. A probe is applied to the area of innervation of the surveyed nerve and temperature is then slowly raised. Patients with nerve injury cannot detect gradual temperature changes and can only react to high temperature when it becomes a painful stimulus.

Another way to diagnose neuropathic pain is pressure sensory testing. This test relies on the patient’s ability to distinguish pressure thresholds between affected and unaffected sides. A probe is applied to patients' skin and pressure is gradually increased; patients indicate when pressure is felt. In two-point discrimination testing, the distance between the two probes (pressure points) is increased and patients are instructed to indicate when two points are distinctly felt. It has been shown that pressure sensory testing results differ significantly between the affected and unaffected side, and that results improve after successful treatments.22 Similarly, compressed nerves lose their ability to transmit stimuli of vibration that can be detected by tuning forks or similar devices.

High-frequency ultrasound (15 MHz linear probe) is often used to diagnose compression and pathology of peripheral nerves. Inflamed nerves that are not compressed may appear edematous with increased blood flow and enlarged.23 In contrast, compressed nerves will appear flat. Unfortunately, pudendal nerves are positioned deep in the pelvis and only the terminal branches such as the dorsal nerve of the clitoris can be seen by ultrasound.

Doppler ultrasound has been advocated as a test to diagnose pudendal nerve entrapment.23,24 Since the nerve courses together with the pudendal artery and vein in a neurovascular bundle, it is hypothesized that compression of the nerve would lead to compression of the vein. During surgery, varicosities of this vein are often encountered in the area of nerve compression. Doppler ultrasound has the ability to detect a gradient in venous flow around the area of compression.

Functional MRI images tissues based on their biological properties and not on their anatomical differences.25 The method applied in assessment of nerve integrity is called “diffusion tensor imaging”. It relies on the ability of water to diffuse more rapidly along nerve fibers rather than perpendicularly. Together, with three-dimensional imaging and advanced computer algorithms, this method may be the future of the diagnosis of pudendal neuralgia. In its current state, this imaging modality does not seem to be accurate enough to diagnose pudendal nerve compression and is viewed as experimental and inconclusive by most.

Until recently, there were no specific radiological findings in patients with pudendal nerve entrapment. Advances in MRI, allow for good visualization of the main trunk of the nerve and terminal branches.

COMPLICATIONS

Pudendal nerve blocks may have side effects from steroids such as agitation and anxiety and elevated blood glucose in diabetics. Placement of the needle for injection may penetrate the nerve, a rare complication causing pain immediately that may last for up to six weeks or longer. Intravascular infiltration of lidocaine and bupivacaine is rare. Initially, the patient may notice a metallic taste. A large bolus can cause significant cardiovascular problems. Aspiration of the injection needle for evidence of blood is not a uniform indicator of safety. Following the infiltration of medicines, transient exacerbation of pain may occur. It may be because of the cold medications (room temperature) or local pressure of the volume of the bolus.

Surgical complications specific to pudendal decompression include injury to a small branch of the nerve. The microsurgical repair can be accomplished. An incomplete transection of the sacrospinous ligament has been reported. Transection of the sacrotuberous ligament resulted in the development of an unstable pelvis in one patient (out of several hundred).28 This is now avoided by using a midline vertical incision in the sacrotuberous ligament. Immediate, total pain relief is unusual. Pre-operative pain, slowly decreasing over several months, should not be considered a complication.

DIFFRENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

- Gender-neutral pathologies: Tarlov cysts, coccygodynia, chronic pelvic pain (CPP), sciatica, persistent genital arousal disorder (PGAD).

- In Males: abacterial chronic prostatitis, prostatodynia, idiopathic proctalgia.

- In Females: vulvodynia, chronic pelvic pain, endometriosis, vaginismus.

Management

Conservative therapy

The mainstay treatment of pudendal neuralgia is conservative therapy.26 Avoidance of injury and pain related to pudendal neuralgia is an important element of treatment. Patients who developed pain as a result of specific exercises should cease immediately. Lifestyle changes and work environment modifications should be implemented to minimize sitting. Approximately 20–30% of patients get better with lifestyle modifications.

Medical therapy can be used in patients who fail lifestyle modifications. The three most important groups of medications used in treatment are muscle relaxants, anticonvulsants, and analgesics.6 Use of both gabapentin and pregabalin for treatment of pudendal neuralgia is not FDA approved, although it is clearly beneficial in reducing pain.

In patients with muscle spasms, pelvic floor physical therapy is the gold standard treatment. It can help distinguish myalgia from neuralgia. The main role of physical therapy is relaxation of the pelvic floor muscles.

In patients who show no improvement in pelvic floor muscle spasm, botulinum toxin injection into the pelvic floor is a good treatment alternative. Administered doses between 50 and 400 units of Botox® are reported in the literature.27

Local anesthetic and steroid injections around the pudendal nerves are important treatment modalities in patients with neuralgia. Injections may be performed unguided and transvaginal in women, or image guided by fluoroscopy, ultrasound, or CT scan. CT scan guided nerve blocks are thought to be the most accurate and reproducible method. In a recent study by Fannuci et al.,28 27 patients with pudendal neuralgia underwent CT-guided pudendal nerve blocks. At 1-year follow-up, 92% showed continued clinical improvement. In our clinical experience, long-term benefits are seen in 25–30% of patients. Figures 6 and 7 show the application of nerve blocks.

Surgical therapy

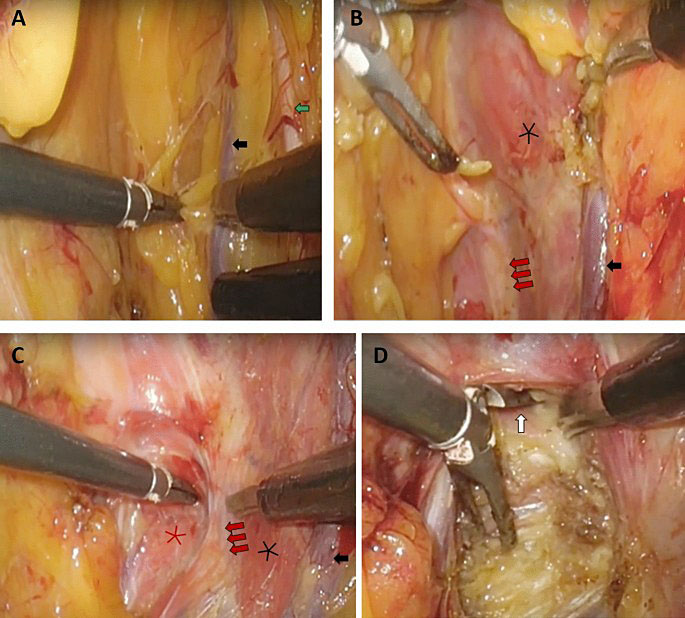

Surgical decompression is the treatment of choice in patients with pudendal nerve entrapment. Proper patient selection is paramount, as treatment success is highly dependent on an accurate diagnosis. There are four described approaches to surgical decompression of the pudendal nerve all of which involve neurolysis to eliminate the possible source of compression. Figure 8 shows surgical techniques of pudendal nerve block.

8

Surgical techniques: techniques of pudendal nerve block.

Transperianal: a semicircular incision is made on the side of the anus on which the nerve is affected. The surgeon then identifies the inferior rectal nerve and follows it blindly with a finger until the pudendal nerve is reached. Adhesions around the pudendal nerve are then bluntly reduced. This approach allows access to the rectal branch and should be limited to patients with only rectal involvement of pudendal neuralgia.

Transgluteal: the transgluteal decompression is currently the most common and successful approach for pudendal neurolysis. A transgluteal incision is made in the location overlying the sacrotuberous ligament. When the ligament is reached, it is transected at its narrowest portion and edges of the ligament are reflected open. The pudendal nerve is found immediately below the ligament together with the pudendal vein and artery. Through this approach, the nerve can be visualized from the subpiriformis fossa to the distal Alcock’s canal. Neurolysis is performed and the sacrospinous ligament is transected. The nerve is then transposed anteriorly to decrease tension. Surgery is concluded by the closure of the subcutaneous fat and overlying skin.

Several modifications have been done to this procedure. A high-power surgical microscope and Nerve Integrity Monitoring System (NIMS, Medtronics) is used to identify the pudendal nerve. After neurolysis Neuragen (Integra), a nerve-protecting wrap, is placed around the nerve to prevent formation/reformation of scar tissue. The nerve is also coated with activated platelet plasma, which contains growth factors promoting nerve healing.29

Another modification is the repair of the sacrotuberous ligament. There is an ongoing argument whether the sacrotuberous ligament provides any significant stability to the sacroiliac joint; opponents of ligament repair believe that a reconstructed ligament may increase the risk of adhesions leading to future entrapment of the nerve. We believe that repaired ligament provides stability to the sacroiliac ligament, and risk of adhesions is minimized by the use of Neuragen.

Transischiorectal: in this technique, an incision is made in the lateral wall of the vagina in women and between the rectum. Dissection is then directed to the ischiorectal fossa on the affected side. Electromyogram is used to direct the surgeon to the area of compression to limit the need of extensive dissection. Similarly to the transperineal approach, access to the pudendal nerve is limited.

Laparoscopic: it does not require transection of the sacrotuberous ligament and provides good visualization of the nerve’s course. Unfortunately, outcomes of laparoscopic decompression have been poor, thus, the procedure has been abandoned. It is possible that with introduction of robotic surgery, which allows greater visualization and precision, endoscopic procedures may again become an option for pudendal nerve decompression.

9

Laparoscopic transperitoneal pudendal nerve and artery release for pudendal entrapment syndrome.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- Pudendal neuralgia is a functional entrapment where pain occurs during a compression or stretch maneuver. The exact mechanism of nerve dysfunction and damage is dependent on its etiology.

- Its diagnosis heavily relies on history and physical examination. Commonly, surgery, vaginal delivery, or pelvic trauma is identified.

- Pudendal nerve entrapment is rarely idiopathic. Tenderness over the ischial spines and Alcock’s canal is consistent with pain originating from the pudendal nerve. Palpation of this area precipitates a tingling sensation commonly known as Tinel’s sign.

- Patients meeting all the required Nantes Criteria have better outcomes from decompression surgery than patients who only partially meet them.

- Pudendal nerve blocks can be performed unguided or with the use of image-guided techniques have both diagnostic and therapeutic value.

- Mainstay treatment is conservative therapy. Avoidance of injury and pain related to pudendal neuralgia is an important element of treatment. Lifestyle changes and work environment modifications should be made.

- The most important group of medications used are muscle relaxants, anticonvulsants, and analgesics. In patients with muscle spasms, pelvic floor physical therapy is gold standard treatment aiming at relaxation of the pelvic floor muscles.

- Surgical decompression has to be done in patients with pudendal nerve entrapment. Proper patient selection is paramount, as treatment success is highly dependent on an accurate diagnosis.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Author(s) statement awaited.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

REFERENCES

Amarenco G, Lanoe Y, Perrigot M, et al. A new canal syndrome: compression of the pudendal nerve in Alcock's canal or perinal paralysis of cyclists. Presse Med 1987;16(8):399. | |

Amarenco G, Lanoe Y, Ghnassia RT, et al. Alcock's canal syndrome and perineal neuralgia. Rev Neurol 1988;144(8–9):523–6. | |

Amarenco G, Savatovsky I, Budet C, et al. Perineal neuralgia and Alcock's canal syndrome. Ann Urol 1989;23(6):488–92. | |

Spinosa JP, de Bisschop E, Laurencon J, et al. Sacral staged reflexes to localize the pudendal compression: an anatomical validation of the concept. Rev Med Suisse 2006;2(84):2416–8, 20–1. | |

Pudendal Nerve Palsy Bicyclist Injury by Dr. Nabil Ebraheim. Available from: https://youtu.be/itJivQNHQPM [Last accessed on 18-06-2018] | |

Campbell JN, Meyer RA. Mechanisms of neuropathic pain. Neuron 2006;52(1):77–92. | |

Hibner M, Desai N, Robertson LJ, et al. Pudendal neuralgia. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2010;17(2):148–53. | |

Shafik A, El Sibai O, Shafik IA, et al. Role of sacral ligament clamp in the pudendal neuropathy (pudendal canal syndrome): results of clamp release. Int Surg 2007;92(1):54–9. | |

Hansen HC. Interstitial cystitis and the potential role of gabapentin. South Med J 2000;93(2):238–42. | |

Waldinger MD, Venema PL, van Gils AP, et al. New insights into restless genital syndrome: static mechanical hyperesthesia and neuropathy of the nervus dorsalis clitoridis. J Sex Med 2009;6(10):2778–87. | |

Labat JJ, Robert R, Delavierre D, et al. Symptomatic approach to chronic neuropathic somatic pelvic and perineal pain. Prog Urol 2010;20(12):973–81. | |

Labat JJ, Riant T, Robert R, et al. Diagnostic criteria for pudendal neuralgia by pudendal nerve entrapment (Nantes criteria). Neurourol Urodyn 2008;27(4):306–10. | |

Choi SS, Lee PB, Kim YC, et al. C-arm-guided pudendal nerve block: a new technique. Int J Clin Pract 2006;60(5):553–6. | |

Peng PW, Tumber PS. Ultrasound-guided interventional procedures for patients with chronic pelvic pain – a description of techniques and review of literature. Pain Physician 2008;11(2):215–24. | |

Thoumas D, Leroi AM, Mauillon J, et al. Pudendal neuralgia: CT-guided pudendal nerve block technique. Abdom Imaging 1999;24(3):309–12. | |

Labat JJ, Robert R, Bensignor M, et al. Neuralgia of the pudendal nerve. Anatomo-clinical considerations and therapeutical approach. J Urol (Paris) 1990;96(5):239–44. | |

Filippiadis DK, Velonakis G, Mazioti A, et al. CT-guided percutaneous infiltration for the treatment of Alcock's neuralgia. Pain Physician 2011;14(2):211–5. | |

Le Tallec de Certaines H, Veillard D, Dugast J, et al. Comparison between the terminal motor pudendal nerve terminal motor latency, the localization of the perineal neuralgia and the result of infiltrations. Analysis of 53 patients. Ann Readapt Med Phys 2007;50(2):65–9. | |

Olsen AL, Ross M, Stansfield RB, et al. Pelvic floor nerve conduction studies: establishing clinically relevant normative data. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003;189(4):1114–9. | |

Snooks SJ, Swash M, Henry MM, et al. Risk factors in childbirth causing damage to the pelvic floor innervation. Int J Colorectal Dis 1986;1(1):20–4. | |

Tetzschner T, Sorensen M, Rasmussen OO, et al. Reliability of pudendal nerve terminal motor latency. Int J Colorectal Dis 1997;12(5):280–4. | |

Walk D, Sehgal N, Moeller-Bertram T, et al. Quantitative sensory testing and mapping: a review of nonautomated quantitative methods for examination of the patient with neuropathic pain. Clin J Pain 2009;25(7):632–40. | |

Greenspan JD. Quantitative assessment of neuropathic pain. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2001;5(2):107–13. | |

Beco J, Mouchel J, Mouchel T, et al. Concerns about the use of colour doppler in the diagnosis of pudendal nerve entrapment. Pain 2009;145(1–2):261; author reply 2. | |

Mollo M, Bautrant E, Rossi-Seignert AK, et al. Evaluation of diagnostic accuracy of Colour Duplex Scanning, compared to electroneuromyography, diagnostic score and surgical outcomes, in Pudendal Neuralgia by entrapment: a prospective study on 96 patients. Pain 2009;142(1–2):159–63. | |

Benson JT, Griffis K. Pudendal neuralgia, a severe pain syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005;192(5):1663–8. | |

Abbott J. Gynecological indications for the use of botulinum toxin in women with chronic pelvic pain. Toxicon 2009;54(5):647–53. | |

Fanucci E, Manenti G, Ursone A, et al. Role of interventional radiology in pudendal neuralgia: a description of techniques and review of the literature. Radiol Med 2009;114(3):425–36. | |

Sariguney Y, Yavuzer R, Elmas C, et al. Effect of platelet-rich plasma on peripheral nerve regeneration. J Reconstr Microsurg 2008;24(3):159–67. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards programme CLICK HERE)