This chapter should be cited as follows:

Chilaka C, Sutton C, et al., Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.418383

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Gynecology Module

Volume 5

Urogynecology

Volume Editors:

Philip Toozs-Hobson, The Birmingham Women’s Hospital, UK

Dr Dudley Robinson, Kings College, London, UK

Chapter

Complex Patients: Elderly and Obese Metabolic Syndrome

First published: July 2023

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

INTRODUCTION

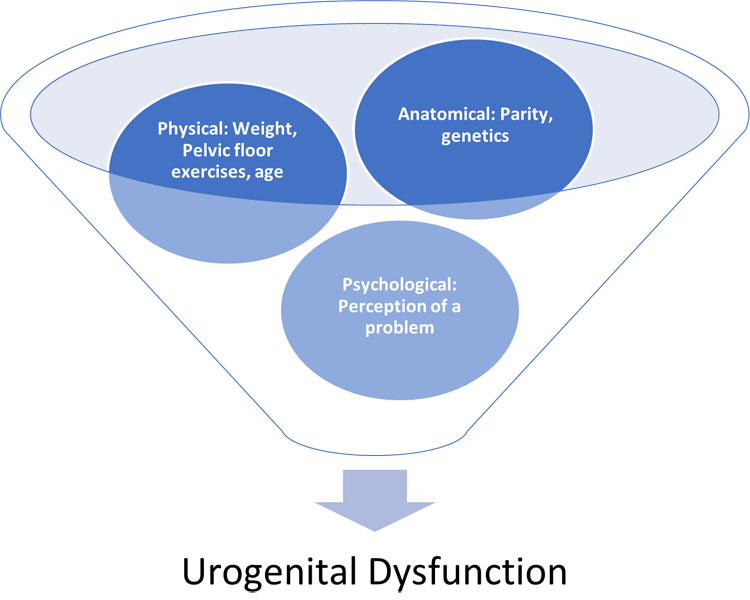

The World Health Organization defines health as “A state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” With this definition it is assumed that we live in an unhealthy world as there are few non-troubled with at least one of these elements. The definition helps clinicians to understand the importance of a holistic approach to the patients. We cannot just simply treat the clinical condition without considering the mental and social impact of a condition. There are few aspects of medicine that are free of this necessity to balance priorities. This fine balance is even more important in urogynecology; a specialty in which condition is heavily subjected to the impact on the quality of life of the patient. Urogynecology includes conditions that can be very difficult to manage and is further complicated by medically complex patients. The urogynecology system not only carries a physical burden, but also a psychological and behavioral burden. When treating conditions such as urogenital prolapse and incontinence, one must address all factors that are contributing to the condition (Figure 1).

1

Multifactorial aspects of prolapse.

There is already an established body of evidence suggesting that there are multiple factors leading to urogenital conditions. When looking at the physical burden on the urogenital tract; the sheer weight associated with a raised body mass index (BMI) can mimic the effect of pregnancy, contributing to stretching and weakness of the muscle and in turn affecting the nerves. The increased intrabdominal pressure increases the static pressure of the bladder resulting in a much lower gradient needed to expel urine through the urethra. This particularly affects women suffering from stress urinary incontinence.

Looking more closely at the tissues of the pelvic floor, disruption of the paraurethral and sub urethral connective tissues are important in maintaining the tensile strength and support to pelvic organs, this is also known as integral theory. Two independent risk factors that contribute to damage of these structures are age and childbirth.4 Vaginal delivery, especially forceps delivery is associated with nerve damage that contributes to the urogenital symptoms. However, there are still limitations to understanding the full extent of histopathological changes with aging and in the post-partum female urogenital tract.5

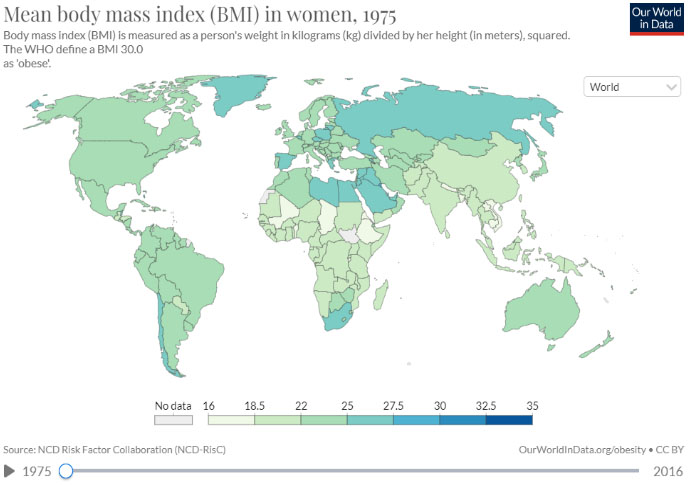

As well as an aging population, we have an ever-increasing rate of obesity. The impact of which is far-reaching. Obesity is defined by the WHO as a BMI of >30. At the last estimate, 28.7% of adults in England are obese and a further 35.6% are overweight but not obese (House of Commons Library 2019). Overall, about 13% of the world’s adult population (11% of men and 15% of women) were obese in 2016 (WHO). It is already recognized that lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) increase with obesity. A recent NICE document6 estimated that in the UK the prevalence overall of urinary incontinence in women is 39.9%.7 Urogynecology are already aware of the changing demographic seen in their services and the impact LUTS have beyond pelvic floor dysfunction. The true prevalence of LUTS in women with obesity is difficult to say as there are multifactorial issues that prevent them from coming forward for help.

|

|

2

World map to show in the worldwide increase in BMI between 1975 and 2016. Reproduced from Ritchie and Roser, 2017 under Creative Commons BY license.1

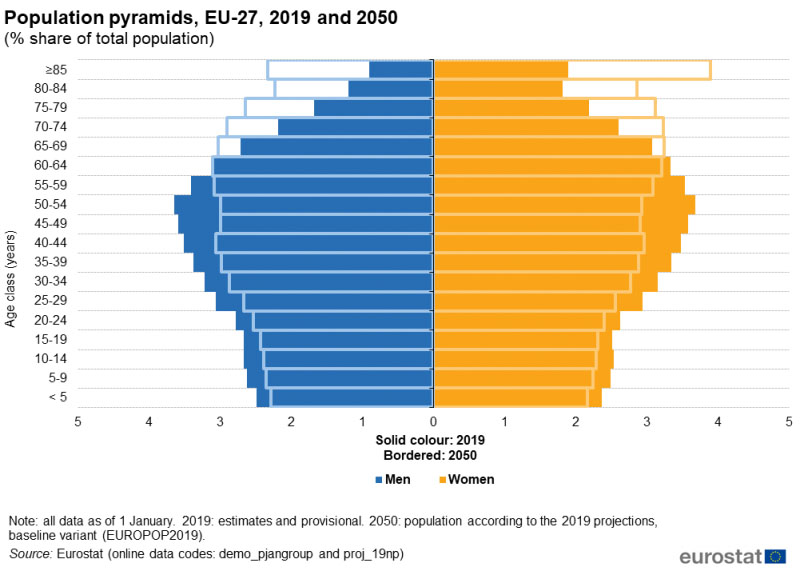

Around one-fifth of the UK population (19%) was aged 65 or over in 2019. The number of people in this age group increased by 23% between 2009 and 2019.8 Between 2015 and 2050, the proportion of the world's population over 60 years will nearly double from 12% to 22% (Figure 2).9 The aging population is a heterogeneous group with some older women living well in later life and others living with advancing frailty. Patients living with frailty and/or obesity present complexities and challenges when managing urogynecology conditions.

3

A chart to show the population projection in Europe between 2019 and 2050. Reproduced from Eurostat © European Union, 1995-20232 under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International.

“Frailty defines the group of older people who are at highest risk of adverse outcomes such as falls, disability, admission to hospital, or the need for long-term care”.10 Frailty is more common in older age and associated with the bodies gradual decline and diminishing physiological reserves, making this population more susceptible to deterioration triggered by minor health events. Despite treating a substantial portion of older women, frailty has not traditionally been considered in urogynecology.

This chapter seeks to look at complicated patients with obesity, metabolic syndrome, and advancing age. There is no doubt that their prevalence in clinic is increasing, and we will need to be more informed in our approach to their management.

OBESITY AND METABOLIC SYNDROME AND ITS IMPACT ON THE FEMALE UROGENITAL SYSTEM

With the growing trend of obesity, it is inevitable that there will be a growing number of women suffering from urinary incontinence. Obesity has two effects; firstly, the direct “physical” effect, but secondly and increasingly recognized, the metabolic effects characterized in “metabolic syndrome”, and this may help explain why the impact of obesity varies between individuals. The situation is further complicated by the psychological effects firstly associated with developing obesity and secondly the impact of treatment and weight loss.

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a common disorder that is increasing in prevalence due to the increase in obesity. MetS includes the three conditions of: diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and obesity.

More specifically, MetS is diagnosed if the patient has any three of the following:11

- Waist circumference more than 40 inches in men and 35 inches in women.

- Elevated triglycerides 150 milligrams per decilitre of blood (mg/dL) or greater (conversation to mmol/l divide by 38.67 so this is 3.9 mmol/L).

- Reduced high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL) less than 40 mg/dL in men or less than 50 mg/dL in women (same conversation so above 1 mmol/l for men and 1.3 for women).

- Elevated fasting glucose of l00 mg/dL or greater.

- Blood pressure values of systolic 130 mmHg or higher and/or diastolic 85 mmHg or higher.

The etiology of MetS is excessive body weight leading to build up of adipose tissue. It is compounded by a lack of physical activity and genetic disposition. This leads to insulin resistance. There is an associated increase in pro inflammatory cytokines because of the enlarged adipose tissues. There is impairment of signaling pathways, which contribute to insulin resistance because of insulin receptor defects and defective insulin secretion.

Fat distribution is an important factor as upper body fat plays a role in developing insulin resistance. There may be a relationship between waist circumference and odds ratios for stress urinary incontinence.12

Pathophysiology

The mechanism of how MetS impacts on the urogenital system is complex and includes cardiovascular, neurogenic, and inflammatory effects. From the cardiovascular perspective, there is a destructive effect of causing damage to the pelvic vascular system, which in turn can lead to dysfunction of the detrusor and sphincter muscles.13 There have been studies to suggest that the prevalence of MetS could be as high as 69.4% in patients with stress urinary incontinence.14

As you may expect with diabetes associated neuropathy, those with diabetes may have less urge incontinence as there is less sensation.13 Though there is a lot of data suggesting that the presence of diabetes, specifically a high HbA1c level,15 worsen LUTS as well as impairs treatment,16 there is, unfortunately, limited data that suggests that reversal of diabetes is unlikely to result in total reversal of symptoms. It is currently unclear to what extent treating MetS will reverse the pelvic vascular changes. Further research into this area is needed.

There is convincing evidence to show that inflammation could be an important contributing factor in LUTS. There are studies that have suggested that there is an association with increased proinflammatory markers and overactive bladder (OAB) especially neuron growth factor (NGF).17 NGF plays an important role in the survival of sensory neurons. Studies have suggested that there are raised urine NGF levels seen in patients with OAB and even higher in patients with OAB wet.

MetS and OAB share common pathophysiology. Obesity is positively related to NGF and is seen in elevated levels in OAB and obesity. It is a neurotrophin found in elevated levels in patients with OAB. MetS also directly affects the autonomic and peripheral neuropathies by altering the transmission of autonomic efferent and peripheral sensory afferents of the bladder.18 This again is an area with little evidence and further research is needed to improve our current limited understanding.

THE EFFECT OF OLD AGE ON THE UROGENITAL TRACT

With age, comes different and increased multifactorial contributors to the changes seen in the pelvic floor and urogenital tract. As women get older, they experience hormonal, muscular, and neurological changes, which all contribute to pelvic floor dysfunction. Age on its own can be seen as an independent risk factor for urinary incontinence (UI) and pelvic organ prolapse (POP) with 37% of women over the age of 80 being affected by POP.19

Worldwide, and in women aged 70 years, more than 40% of the female population is affected by urinary incontinence.3

Physiology of the aging urogenital tract

The skeletal muscles are negatively affected by age and as a result, the pelvic floor suffers. There is atrophy of the muscles. This affects both the anterior and posterior compartments. With increasing age there is a change in the paraurethral collagen with a slower fiber turnover.20 Not only does it slow but there is a higher collagen concentration decreasing the proteohycan/collagen ratio. Though this change increases load-bearing ability, it reduces the elasticity.

The detrusor muscles suffer repeated small insults leading to changes of the bladder architecture from muscle to more collagenous material. As collagen contracts less than muscle, it is less distensible. These changes can result in delayed sensation from the nerve changes and reduced capacity from the increased stiffness, thus leading to delayed first sensation and reduced capacity. This increases the possibility of urgency and urge incontinence. In addition, the reduced contractility of the bladder can also result in incomplete emptying of the bladder.

These changes are also seen in the urethra, which will present in a reduction of the urethral closing pressure leading to a failure of the sphincter as well as reduced distensibility during voiding leading to a reduced flow rate.

There may be an association with decreased amplitude in pudendal and perineal nerve muscles associated with increased vaginal deliveries.19 As a result of the denervation, there is further atrophy of the skeletal muscles as well as dysfunction of the nerves.

Estrogen plays an important role in the health of the female urogenital system. There are estrogen receptors seen within the epithelial tissues of: the bladder, trigone, urethra, vaginal mucosa, levator ani muscles as well as support structures such as utero-sacral ligaments and pubo-cervical fascia.21 Estrogen maintains the collagen content of these epithelial layers. Estrogen also maintains an acidic environment allowing the normal vaginal flora to flourish and in turn reduce the risk of infection to the urogenital tract. Estrogen also aids maintenance of the genital blood flow.19 Lack of estrogen can lead to thinning of the vaginal epithelium, reduced vaginal secretion, narrowing and soreness of the vagina, dysuria, and frequency. The reduced blood flow can have a detrimental effect on the urethral muscles; there is a net of vessels around the urethra and they contribute to one-third of the urethral pressure, this vasculature is reduced in the postmenopausal woman.22

Hence the clinical impacts of aging are as follows:

- Increased post-void residual volume.

- Reduced urethral closure pressure.

- Urogenital atrophy.

- Tendency to pelvic organ prolapse.

- Vaginal soreness.

- Reduced urinary warning time (reduced sensation).

One can therefore begin to understand why LUTS and incontinence are common with advancing age and how co-morbidities and polypharmacy impacts on bladder symptoms.

The prevalence of MetS in the older frailer women is less understood, but emerging studies have suggested that the presence of MetS is associated with an increased risk of frailty.23 MetS is associated with worsening physical and psychological outcomes after the menopause.24

APPROACH TO CARE

Obesity and metabolic syndrome

When approaching patients with MetS a holistic approach must be taken. Often these patients will have a raised BMI and we know that those with a raised BMI are less likely to seek help for their conditions. One should not underestimate the psychological impact that their weight is having on them and should offer further counseling if needed as there is a role that mental resilience plays on the severity of symptoms.25

There has been a long established correlation between pregnancy and cardiovascular disease, which was highlighted in the Framingham Study. Over time, research has progressed to emphasize that obesity has a strong correlation with the intrauterine environment the fetus is exposed to. It suggests that maternal BMI is closely associated with childhood obesity. As the general population are becoming obese, there will be a continued ripple effect of maternal obesity and childhood obesity and in turn and increased prevalence of metabolic syndrome.

Initial History

As well as the routine urogynecology history, clinicians should try and screen for metabolic dysfunction. If a patient presents with polyuria, consider polydipsia and diabetes. Probe for possible metabolic conditions in the past medical history such as polycystic ovarian syndrome (which will put them at a higher risk of diabetes mellitus). Given the close association between raised BMI and obstructive sleep apnoea, there may be some merits in screening for obstructive sleep apnoea as we know that there is a correlation with obstructive sleep apnoea and nocturia.26 Where it is appropriate, ask sensitively if it is ok to discuss their weight and weight-loss journey. The authors would suggest the use of terms such as "unhealthy weight" rather than "heavy/large".

Examination

Ensure that you calculate the BMI for the patient. This will help to further assess the patient and if they are obese. This allows more information that may help to make the patient eligible for further intervention such as referral to the dieticians or weight-loss services in the region. It will help in counseling to help with targets for weight loss.

Examination should consist of an abdominal examination and pelvic examination. A post-void residual test can be done on the bedside depending on clinical need. A blood pressure reading may also help highlight undiagnosed high blood pressure if suspecting MetS. Observing hyperpigmentation in the thighs and arms may also help to direct clinicians to the possibility of diabetes mellitus.

It is not routine to check random blood sugar levels in the urogynecology setting, however it is routine to get a urinary sample for urinalysis. If glucose is seen with the urine, the general practitioner should be informed for further investigations.

Initial investigation

The initial investigation is very similar to most gynecological settings (Table 1).

1

Different types of investigations used in Urogynecology.

Investigation | Example | Rational |

Bladder diary | – | Establish behavioral patterns of micturition and objectively quantify urine loss. |

Quality-of-life questionnaire | ePAQ questionnaire, ICIQ | This is very important to get an insight into the main concerns of the patient and about the problems: it gives the patient time to really think about the condition and aid the clinician in directing the approach and help needed. |

Urodynamics | Laboratory, video, ambulatory | In cases where anticholinergics have failed or suspicions of poor bladder capacity or neurogenic cause to incontinence. |

Transvaginal ultrasound scan | – | If concerns of pressure symptoms that may be attributed to pelvic pathology if is difficulty with deep palpation. |

Blood tests | HbA1c | If elevated may indicate unknown diagnosis of diabetes or indicate poor glycemic control in an known diabetic. Although not routinely check in the urogynecology services, you can signpost to primary care to be checked. |

Blood pressure | – | Check for signs of metabolic syndrome and initiation of certain medication. If elevated, you can sign post to primary care to be checked. |

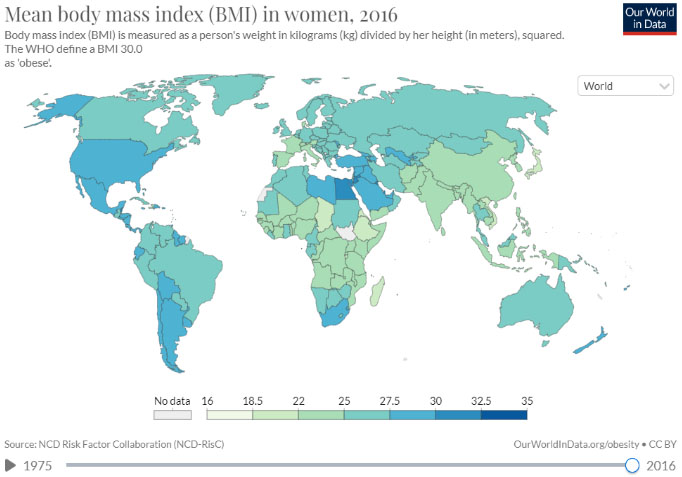

Management

There are limited data on the specific approach to take when managing women with MetS and pelvic floor dysfunction. In general, patients should be supported and encouraged to reduce their weight to a healthier weight that is likely to improve their symptoms. Depending on the local health services this may include weight-loss programs, dietetic input, medications (e.g. Orlistat, Liraglutide), and/or surgery. The authors' recommendations from the current evidence base and the pathophysiology behind MetS, are as follows:

Education

Supporting the patient to understand the relationship between their weight/MetS and their symptoms is critical. When the patient can relate the symptoms to the underlining mechanics it will help with understanding and managing expectations. You must let them then know that optimizing their general health and reducing their weight can help improve the presence of symptoms.

Weight loss

Weight loss is an important aspect in helping to treat urogenital symptoms. Studies have suggested that weight losses between 5% and 10% of body weight were sufficient for significant urinary incontinence benefits.27 Surgical weight loss can help improve continence symptoms from 67% to 37% after 12 months.12 Bariatric surgery has also been shown to improve symptoms relating to quality-of-life assessments.28 Depending on where the patient is in their weight-loss journey you may need to signpost them to general weight-loss services, their primary care physician, or specialist obesity services to support them to achieve this.

4

Pictural summary of initial management of patients with obesity and metabolic syndrome.

Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) in patients with MetS/obesity

In urogynecology the most important initial intervention for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence is physiotherapy. This remains true in patients with MetS but with extra emphasis on weight loss to ensure maintenance of results as surgical options may be limited in a raised BMI. Weight loss on its own can improve the symptoms. SUI symptoms can be significantly improved with bariatrics surgery over 2–5 years.29

Overactive bladder in patients with MetS/obesity

Obesity is a statistically significant risk factor for OAB and detrusor overactivity and so weight loss is highly recommend in patients with MetS.30 Diabetic cytopathy can be diagnosed with the triad of:

- Decreased bladder sensation.

- Increased bladder capacity.

- Impaired detrusor contractility.31

Diabetic neuropathy, particularly autonomic neuropathy, contributes to this condition, however the majority of such patients will have confounding urogenital symptoms so it can be hard to isolate the etiology.32 Unfortunately, autonomic neuropathies are thought to be irreversible complications of diabetes. When treating OAB in patients with an elevated BMI it is important to ensure drug treatments do not contribute to further weight gain. The anti-cholinergic used to treat OAB do not commonly cause weight gain, however, significant dry mouth can cause some individuals to drink/eat to counteract this side effect. Mirabegron is not known to cause weight gain and there is a suggestion that it may be beneficial in metabolic disorder although further evidence is required.33

Pelvic organ prolapse in patients with MetS/obesity

The initial management of pelvic organ prolapse is physiotherapy. There seems to be less of an association with the severity pelvic floor prolapse (POP) and raised BMI.34 There seems to be an association between women with MetS with a raised waist circumference and elevated triglycerides and developing significant POP. Optimizing MetS is essential for long-term management and prevention. Surgical management should remain an option where necessary. It may be limited to the anesthetic concerns of patients with long-standing disease associated with MetS. Also, the outcome may be worse with a BMI greater than 35. Where surgery is not an option, vaginal pessaries can be used where appropriate. However studies have shown that obesity is a risk factor for pessary failure in the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse.35

Elderly care medicine

Practical considerations

Due to the presence of multimorbidity and frailty you may need to allocate longer to complete a holistic assessment of an older woman presenting to your service with incontinence symptoms. You may wish to consider assessing jointly with a geriatrician. This may lead to increased expenses for the department, but ultimately will allow more holistic patient care.

History

Many older women do not seek help for their bladder symptoms believing and accepting it is part of normal aging. Older women should be routinely yet sensitively asked if they have any continence symptoms. Once identified a comprehensive history should be taken, in particular, noting the presence of co-morbidities, medications, and social history. Social history should include information about function, i.e., where do they live, how do they mobilize, how do they get to the toilet, do they need support with their activities of daily living? It is helpful to quantify presence and degree of frailty that older women may be living with. A tool such as Rockwood Frailty Score can be useful to assess this (see link in references).36 It is also important to identify the presence or absence of other common geriatric conditions such as falls and cognitive impairment as they commonly co-exist and may affect your approach/management. There is clear evidence linking falls with incontinence; Foley et al. found a positive association between both stress and urge symptoms and falls; noting the larger the volume of urine lost the higher the risk.37 You should therefore also ask whether the patient has any difficulties with their memory affecting their day-to-day life or whether they have had any falls in the last 6 months. The geriatric giants of falls, immobility, incontinence, and cognitive impairment often co-exist but may not be formally diagnosed.38

Collateral history – taking a history from a family member or carer is an important part of information gathering when assessing older women, especially in those with cognitive impairment or those who rely on family or carers for support. Understanding the perspective of the carers is also helpful and should be born in mind when generating a patient-centered plan. However, any clinician looking after older patients should be aware of and alert to potential safeguarding concerns and always act in the best interest of the patient.

Bowels – aging of the gastrointestinal tract, co-morbidities, immobility, and medication mean that constipation is a common complaint in older patients. Enquiry into the bowel history of your patient should be routine as optimization of bladder symptoms often involves optimization of the bowels.

HISTORY CHECKLIST

Table 2 itemises the different aspects of a medical history needed in thoroughly assessing the elderly patient and the rationale why.

2

History needed in thoroughly assessing the elderly patient and the rationale.

Item | Rationale |

Past medical history | Multimorbidity common with aging and may be causing/exacerbating urogenital symptoms |

Drug history | Polypharmacy common with aging and may be causing/exacerbating urogenital symptoms Ability to self-medicate may impact on treatment choice |

Cognitive screening question | Avoid oxybutynin PO May impact on compliance |

Social history | May suggest need to refer to allied health professionals/social worker |

Bowel history | Constipation common and may be impacting on urogenital function |

Falls | Falls' risk is increased in older women with incontinence |

Collateral history | Helpful to get information from carers/family especially if your patient has cognitive impairment |

Examination

As part of your physical examination, you should also note mobility issues (how does the patient transfer/mobilize in the clinic room), vision and hearing impairments. If there are any functional or sensory impairments this may impact on how you share information/proceed with treatments. It is useful to examine the external genitalia for the presence or absence of vaginal atrophy as well as usual routine physical examination. In a patient with constipation, a digital rectal examination can be useful to exclude the presence of fecal impaction that can impact on bladder emptying.

Initial investigations

Initial investigations are likely to be similar to your usual work up in this patient group although you will need to consider whether more invasive investigations such as urodynamics are likely to be tolerated, practical, and useful in your patient. A post-void bladder scan is helpful although post-void residual volumes can increase with age so bear this in mind when interpreting the results.39 Urinalysis will often be positive for leucocytes and/or nitrites and may not be clinically relevant as asymptomatic bacteriuria is more common with increasing age (6–16% of women over 65, rising to 15–35% of women in long-term care facilities,.40 The absence of leucocytes and nitrite can be reassuring in a patient with possible infective symptoms, however, remember nitrites are positive with gram-negative bacteria, so enterococcus, for example, will not produce nitrites.41 The presence of glucose or protein in the urine may indicate underlying diabetes or renal disease so can be useful to identify and advise the primary care physician for further assessment.

Completion of a bladder diary can also be a challenge for older women living with frailty. Dexterity issues are common meaning measurement of urine output is difficult. You may need to modify this assessment by simply asking for a record of voids/pad changes and an indication whether the void was "large" or "small" and whether the pad was "damp", "wet", or "very wet" to give you an indication of the pattern of symptoms.

Management

Lifestyle/education

As usual attention to fluid intake (quantity/type) is important and counseling to optimize key. Many older women will avoid drinking to reduce incontinence episodes hence education about type and amount of fluid is important. If there are functional impairments, you may need to involve other allied health professionals such as physiotherapists if your patient is at risk of falls/has poor mobility, or occupational therapists for optimization and assessment of activities of daily living.42 A social work referral may also be required if additional support is needed. Remember that many older women are reliant on family or carers to shop for them or support them so any lifestyle intervention/education should also be delivered to them.

Medication review

Polypharmacy is common in older women as the presence of co-morbidities increases.38 You should consider how each medication may be impacting on your patient’s bladder/bowel symptoms and suggest alternatives/discontinuation to the primary care physicians. Reducing the burden of polypharmacy whilst optimizing quality of life is important in the development of a management plan for an older woman, particularly those living with increasing frailty.

It is also important to think about mode of delivery of medication in an older adult. Does she need assistance with medication, does she have a blister pack, who would apply a patch if one were needed and the patient is unable to do it herself. A useful strategy to employ when prescribing in older women is "start low and go slow" as side effects can be more common.

Optimization of co-morbidities

You should consider how your patient’s co-morbidities may be impacting on her bladder and bowel symptoms. As we have already discussed, elevated BMI can have a deleterious effect on the pelvic floor and weight-loss management may be relevant (see Table 3 for examples of other common comorbidities and potential impact on continence).

3

Different body systems and their possible impact on the elderly patient due to any underlying pathology.

System | Pathology (EG) | Possible impact |

Loco-motor system | Osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis | Reduced manual dexterity Reduced mobility – increased time to mobilize to the toilet, difficulty undressing/dressing |

Neurological system | Stroke, Parkinsons' disease | Impaired mobility and function and/or cognition |

Cardiovascular system | Hypertension, heart failure | Edema contributing to nocturnal polyuria Medical adversely impacting on urogenital function |

Respiratory system | COPD, obstructive sleep apnoea, chronic cough | Stress symptoms due to cough Increased OAB with sleep apnoea |

Vaginal atrophy

Management of vaginal atrophy can improve symptoms of OAB and reduce urinary tract infection in older women.43 You may wish to consider alternatives to standard topical estrogen by utilizing options such as the vaginal "e-string" in selected patients. The vaginal “e-string” ™ provides long-term (up to 3 months), slow-release estrogen in the vagina without the patient needing to administer the estrogen themselves. This is a good option for patients with limited dexterity and/or cognitive impairment or may just be the preferred choice for some older ladies.

Overactive bladder

As well as lifestyle advice, pelvic floor exercises, if feasible, can help strengthen the pelvic floor and reduce episodes of incontinence in older women with OAB.44,45

If conservative management is not successful a trial of medication may be required. For most patients, the first-line choice will be an anti-cholinergic medication. There are a few important considerations in older women when utilizing anticholinergics:

- Risk of cognitive impairment – anticholinergic use is known to cause worsening of cognition in some older adults. This is well recognized in patients with known cognitive impairment but can affect any older adults. If your patient has known or suspected cognitive impairment avoid oral oxybutynin. You can consider a trial of topical oxybutynin or solifenacin, fesoterodine and trospium have all been shown to cause less cognitive side effects. When looking at oxybutynin, it is metabolized into the metabolite N-desethyloxybutynin (DEO). DEO is able to cross into the central nervous system and contribute to cognitive impairment. Studies have suggested that the transdermal patch eliminates pre-systemic metabolism and therefore has lower levels of DEO.46 In the UK the NICE guidelines6 recommend avoiding oral oxybutynin in women over 65 with cognitive impairment and suggest trospium and fesoterodine instead.

- Risk of increasing anticholinergic burden – many medications have an anticholinergic effect to varying degrees. The addition of an anticholinergic may increase this cumulative effect leading to deleterious side effects. There are currently electronic methods and apps to help to calculate the anticholeretic burden such as the website acbcal (http://www.acbcalc.com/).47

- Other side effects – older people are more likely to develop drug side effects than younger people. Particular anticholinergic side effects that can be troublesome to older adults include dry mouth (may adversely affect oral intake), constipation and cognitive impairment as already mentioned.

It is important to counsel your patient and their carer regarding possible side effects particularly cognitive change. Anticholinergic (AC) medications have been linked to impaired cognition primarily in older adults and increased risk of dementia. The biological basis for this is yet unknown but it is speculated that direct impairment of cholinergic neurons may underlie these effects.48 An alternative option for treating OAB in older women is Mirabegron (Betmiga) in accordance with NICE guidance.6

Pelvic organ prolapse

This is often successfully managed in older ladies by utilizing a vaginal pessary thus improving symptoms and avoiding the need for surgery.49 Management of any concurrent constipation is also of importance. There is scope for surgical intervention and decisions for such should be individually assessed with risks weighed up. Age alone is not an indication to deny surgical intervention.

Other considerations

Special mention must be made regarding older adults living with dementia or other cognitive impairments. Patients with dementia often develop incontinence for a variety of reasons already discussed as well as cognitive impact on maintenance of continence. Carer strain is often evident in patients with dementia living at home with their loved ones who may be struggling to manage the burden of their care. Sadly, incontinence is often the tipping point that leads an older adult with dementia to go into a care home. Simple measures can be helpful. Consider signage on the toilet/bathroom door, suggest the toilet door is left open to make it easier for the patient to find. Try a prompted voiding routine where the patient is reminded to go to the toilet at regular intervals throughout the day. Dementia charities will often have helpful tips for carers you could signpost to.

Surgical interventions in older women

There is increased morbidity and mortality when operating on patients with an increased age. This should be balanced with the fact that the absolute risk of any urogynecological complications is low.50 We do know that there is an increased risk of delirium in older patient’s peri-operatively, in particular the anesthetic used may contribute to this. A small study suggest that 1 in 12 women ≥60 years may have significant delirium on the day of prolapse surgery, however the 7-day incidence is comparable to other elective non-cardiac surgery cohorts..51 This suggests that the urogynecology population is not at greater risk than the other surgical specialities in terms of post-operative delirium.

The essence of urogenital surgery is quite simple and often minimally invasive. Prolapse surgery is to reduce the bulge in the vagina and improve patients’ symptoms but applying buttress sutures to support the vaginal facia. This procedure that can be performed under regional anesthetic with a short turnover time for patients. Surgical options such as colpocleisis (in which the vagina is completely closed to reduce a prolapse) can be performed under local anesthetic. Surgery for SUI can also be tailored to the patient, as a minimally invasive option would be bulkamid, which now can be performed in the outpatient setting. Just like in younger patients, patient selection is often more important that performing the actual procedure, and even more so in patients at their frailty imposes further risks.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- Measurement of BMI is important as a raised BMI increases the risk of pelvic organ prolapse, urinary incontinence, and overactive bladder syndrome.

- Weight-loss management is the primary intervention in the management of patients with MetS.

- Be aware of other metabolic conditions that may also be present in patients with a raised BMI (e.g., diabetes, hypertension) as by optimizing these, the symptoms may improve, but are unlikely to be totally reversible.

- Consider running a joint elderly care and urogynecology clinic to allow a comprehensive approach to patients.

- Vaginal estrogen therapy can help improve most urogenital symptoms during and after the menopause.

- Consider co-morbidities and polypharmacy when assessing the older woman.

- A holistic approach is key to the assessment and management of patients with MetS and older patients living with frailty. Remember you are not just treating the patient, but you are treating them, their environment, and their mental health.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Author(s) statement awaited.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

REFERENCES

Ritchie H, Roser H. Obesity. Our World in Data 2017 [Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/obesity]. | |

Eurostats. Ageing Europe – statistics on population developments 2020 [Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Ageing_Europe_-_statistics_on_population_developments]. | |

Milsom I, Gyhagen M. The prevalence of urinary incontinence. Climacteric 2019;22(3):217–22. | |

Liu X, Zhao Y, Pawlyk B, et al. Failure of elastic fiber homeostasis leads to pelvic floor disorders. Am J Pathol 2006;168(2):519–28. | |

De Landsheere L, Munaut C, Nusgens B, Maillard C, Rubod C, Nisolle M, et al. Histology of the vaginal wall in women with pelvic organ prolapse: a literature review. Int Urogynecol J 2013;24(12):2011–20. | |

Excellence NIfHC. Urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse in women: management. In: Excellence NIfHC, ed., 2019. | |

Cooper J, Annappa M, Quigley A, et al. Prevalence of female urinary incontinence and its impact on quality of life in a cluster population in the United Kingdom (UK): a community survey. Prim Health Care Res Dev 2015;16(4):377–82. | |

Library HoC. Housing an ageing population: a reading list. In: Library HoC, ed., 2021. | |

WHO. Ageing and health. 2022. | |

Young J. Frailty – what it means and how to keep well over the winter months 2013 [Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/blog/frailty/#:~:text=In%20medicine%2C%20frailty%20defines%20the,health%20and%20social%20care%20professionals]. | |

Swarup S, Goyal A, Grigorova Y, et al. Metabolic Syndrome. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. Copyright © 2022, StatPearls Publishing LLC., 2022. | |

Subak LL, Richter HE, Hunskaar S. Obesity and Urinary Incontinence: Epidemiology and Clinical Research Update. Journal of Urology 2009;182(6S):S2–S7. | |

Otunctemur A, Dursun M, Ozbek E, et al. Impact of metabolic syndrome on stress urinary incontinence in pre- and postmenopausal women. Int Urol Nephrol 2014;46(8):1501–5. | |

Ströher RLM, Sartori MGF, Takano CC, De Araújo MP, Girão MJBC. Metabolic syndrome in women with and without stress urinary incontinence. International Urogynecology Journal 2020;31(1):173–9. | |

Papaefstathiou E, Moysidis K, Sarafis P, et al. The impact of Diabetes Mellitus on Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in both male and female patients. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews 2019;13(1):454–7. | |

James R, Hijaz A. Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms in Women with Diabetes Mellitus: A Current Review. Current Urology Reports 2014;15(10):440. | |

MENG E, LIN W-Y, LEE W-C, et al. Pathophysiology of Overactive Bladder. LUTS: Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms 2012;4(s1):48–55. | |

Hsu L-N, Hu J-C, Chen P-Y, et al. Metabolic Syndrome and Overactive Bladder Syndrome May Share Common Pathophysiologies. Biomedicines 2022;10(8):1957. | |

Wente K, Dolan C. Aging and the Pelvic Floor. Current Geriatrics Reports 2018;7(1):49–58. | |

Ulmsten U, Falconer C. Connective tissue in female urinary incontinence. Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology 1999;11(5):509–15. | |

Gebhart JB, Rickard DJ, Barrett TJ, et al. Expression of estrogen receptor isoforms alpha and beta messenger RNA in vaginal tissue of premenopausal and postmenopausal women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2001;185(6):1325–30, discussion 30–1. | |

Rud T, Andersson KE, Asmussen M, et al. Factors maintaining the intraurethral pressure in women. Invest Urol 1980;17(4):343–7. | |

Buchmann N, Spira D, König M, Demuth I, Steinhagen-Thiessen E. Frailty and the Metabolic Syndrome – Results of the Berlin Aging Study II (BASE-II). J Frailty Aging 2019;8(4):169–75. | |

Cengiz H, Kaya C, Suzen Caypinar S, Alay I. The relationship between menopausal symptoms and metabolic syndrome in postmenopausal women. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2019;39(4):529–33. | |

Israfil-Bayli F, Lowe S, Spurgeon L, et al. Managing women presenting with urinary incontinence: is hardiness significant? International Urogynecology Journal 2015;26(10):1437–40. | |

Doyle-McClam M, Shahid MH, Sethi JM, et al. Nocturia in Women With Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Am J Lifestyle Med 2021;15(3):260–8. | |

Wing RR, Creasman JM, West DS, et al. Improving urinary incontinence in overweight and obese women through modest weight loss. Obstet Gynecol 2010;116(2 Pt 1):284–92. | |

McDermott CD, Terry CL, Mattar SG, et al. Female Pelvic Floor Symptoms Before and After Bariatric Surgery. Obesity Surgery 2012;22(8):1244–50. | |

Subak LL, Richter HE, Hunskaar S. Obesity and urinary incontinence: epidemiology and clinical research update. J Urol 2009;182(6 Suppl):S2–7. | |

Zacche MM, Giarenis I, Thiagamoorthy G, et al. Is there an association between aspects of the metabolic syndrome and overactive bladder? A prospective cohort study in women with lower urinary tract symptoms. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 2017;217:1–5. | |

Hunter KF, Moore KN. Diabetes-associated bladder dysfunction in the older adult (CE). Geriatric Nursing 2003;24(3):138–45. | |

Kaplan SA, Te AE, Blaivas JG, et al. Urodynamic Findings in Patients With Diabetic Cystopathy. The Journal of Urology 1995;153(2):342–4. | |

Bel JS, Tai TC, Khaper N, et al. Mirabegron: The most promising adipose tissue beiging agent. Physiol Rep 2021;9(5):e14779. | |

Rogowski A, Bienkowski P, Tarwacki D, et al. Association between metabolic syndrome and pelvic organ prolapse severity. International Urogynecology Journal 2015;26(4):563–8. | |

de Albuquerque Coelho SC, Brito LGO, de Araujo CC, Juliato CRT. Factors associated with unsuccessful pessary fitting in women with symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse: Systematic review and metanalysis. Neurourol Urodyn 2020;39(7):1912–21. | |

Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ 2005;173(5):489–95. | |

Foley AL, Loharuka S, Barrett JA, et al. Association between the Geriatric Giants of urinary incontinence and falls in older people using data from the Leicestershire MRC Incontinence Study. Age and Ageing 2012;41(1):35–40. | |

Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, et al. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. The Lancet 2012;380(9836):37–43. | |

Lau H-H, Su T-H, Huang W-C. Effect of aging on lower urinary tract symptoms and urodynamic parameters in women. Taiwanese Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2021;60(3):513–6. | |

Rowe TA, Juthani-Mehta M. Urinary tract infection in older adults. Aging Health 2013;9(5):519–28. | |

Orenstein R, Wong ES. Urinary tract infections in adults. Am Fam Physician 1999;59(5):1225–34, 37. | |

Isaacs B. The Challenge of Geriatric Medicine: Oxford University Press, 1992:244. | |

Cardozo L, Lose G, McClish D, et al. A systematic review of the effects of estrogens for symptoms suggestive of overactive bladder. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 2004;83(10):892–7. | |

Bo K, Fernandes A, Duarte T, et al. Is pelvic floor muscle training effective for symptoms of overactive bladder in women? A systematic review. Physiotherapy 2020;106:65–76. | |

Dumoulin C, Cacciari LP, Hay‐Smith EJC. Pelvic floor muscle training versus no treatment, or inactive control treatments, for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2018(10). | |

Kennelly MJ. A comparative review of oxybutynin chloride formulations: pharmacokinetics and therapeutic efficacy in overactive bladder. Reviews in Urology 2010;12(1):12. | |

Rabino DRKaS. ACB Calculator [Available from: http://www.acbcalc.com]. | |

Risacher SL, McDonald BC, Tallman EF, et al. Association between anticholinergic medication use and cognition, brain metabolism, and brain atrophy in cognitively normal older adults. JAMA Neurology 2016;73(6):721–32. | |

Griebling TL. Vaginal pessaries for treatment of pelvic organ prolapse in elderly women. Current Opinion in Urology 2016;26(2):201–6. | |

Sung VW, Weitzen S, Sokol ER, et al. Effect of patient age on increasing morbidity and mortality following urogynecologic surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006;194(5):1411–7. | |

Ackenbom MF, Zyczynski HM, Butters MA, et al. Postoperative delirium in older patients after undergoing pelvic organ prolapse surgery. International Urogynecology Journal 2022:1–9. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards programme CLICK HERE)