This chapter should be cited as follows:

McKinney JL, Keyser LE, Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.418043

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Gynecology Module

Volume 7

Fistula

Volume Editors:

Professor Ajay Rane, James Cook University, Australia

Dr Usama Shahid, James Cook University, Australia

Chapter

Physiotherapy in the Context of Fistula Management

First published: October 2022

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

Elsewhere in this volume fistula types, etiologies, treatments, and more have been described. The purpose of this chapter is to outline the role of physiotherapy and other rehabilitative care in the context of pre- and post-operative care for women with fistula. While incorporating the most recent literature where available, the chapter has been adapted from a larger work on the subject, the open access resource: Implementing Physical Rehabilitation Services into Comprehensive Fistula and Maternity Care: A Training Guide for Health Care Workers. This full-length training guide was developed as part of the Fistula Care Plus Project, with support from EngenderHealth, USAID, and Mama LLC and provides a more thorough tutorial of physiotherapy in fistula care, including evaluation and treatment. Interested readers are directed to that resource for education, templates, and sample exercise programs. It is available for free download in Swahili, Portuguese, French, and English (https://www.themamas.world/training-guide).

INTRODUCTION

Physiotherapy is one of several disciplines that falls under the umbrella of "rehabilitation services". Investment in quality rehabilitation services minimizes the burden of disability associated with a health condition and may offer several cost benefits, including the following: decreased length of hospital stay; improved short- and long-term health outcomes, reducing the need for expensive medical procedures or repeat surgeries; and optimized mobility and function, enabling women to meaningfully (and financially) contribute to her family and community.1

Physiotherapy is a healthcare discipline that universally focuses on restoration, optimization, and maintenance of human function.2 As such, physiotherapists work with individuals and populations, across the lifespan, and across all manner of health conditions, health settings, and practice environments.

Challenges to physiotherapy service delivery

The global need for physiotherapy and rehabilitation services, along with the severe lack of a sufficient rehabilitation health workforce to meet this need has been established by several publications in recent years.3,4 Cieza et al. used information from the 2019 Global Burden of Disease and Disability research to document the global need for rehabilitation. They conclude that musculoskeletal disorders contributed the most to disability prevalence and that at least one in every three people worldwide requires rehabilitation at some point in the course of their injury or illness. They further note the gap in the rehabilitation workforce and issue a call for health system strengthening, especially at the primary care level.3 Gupta et al. report that 92% of the global burden of disease is related to causes requiring some level of physical rehabilitation and yet only 50% of countries can provide rehabilitation to approximately 20% of those in need.4 Separately, Howard-Wilsher et al. conducted a systematic review on rehabilitative care and concluded that rehabilitation services should have the same priority in health systems as conventional medical treatments.5 Lastly, other authors have documented gross short falls in the rehabilitative care workforce in both high- and low-resource settings.6,7,8,9

THE INTERNATIONAL CLASSIFICATION OF FUNCTION, DISABILITY, AND HEALTH: A GUIDE FOR PHYSIOTHERAPY AND REHABILITATION SERVICE DELIVERY

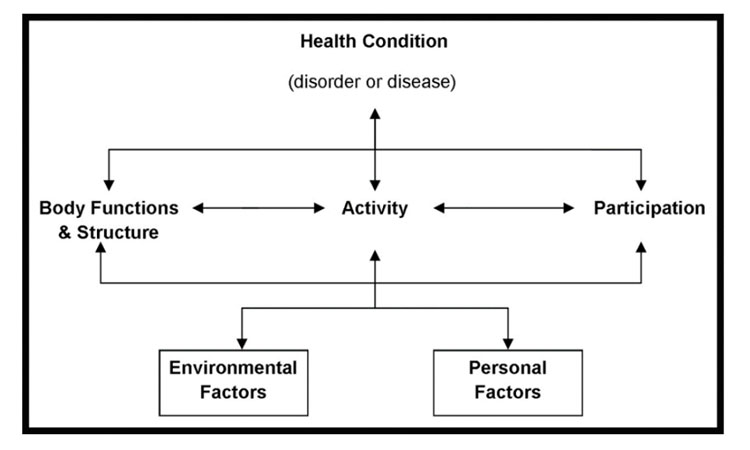

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) provides a framework, pictured below, that helps us to understand that anyone can experience a health condition that causes some level of disability. This may be permanent (long-term) or temporary (short-term). It normalizes the experience of disability as a human experience that we will all have at some point in our lives. It shifts the focus from the cause of disease to its impact on a person’s daily life. It helps us to measure health and not just disease, injury, or illness.10

1

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) model. From Keyser and McKinney, 2019,11 with permission.

This framework places the individual at the center of their care. It encourages a multi-disciplinary team approach to helping them achieve the best possible health outcome – their most optimal level of function.10 The ICF framework helps to determine who will require which type(s) of services or treatments. It serves as a problem-solving tool. It helps all members of the healthcare team to understand individual needs and allows for collaboration and task sharing or task shifting.10

The ICF gives us a framework to understand how a disease, illness, or injury impacts how we function in daily life, how we interact with the world around us, and how the world around us influences our experience of disease, illness, or injury. It also guides us to identify contextual factors in the environment and within each individual – both positive and negative – that influence health, predict treatment needs, and guide outcomes.

The ICF identifies three levels of function: (1) the body and its structures (parts), (2) the person and their ability to perform daily activities for themself, (3) the person in a social context and their ability to interact with and participate in family and community life.10

It is against this backdrop that we can begin to understand physiotherapy in the context of women’s health, and specifically for women with fistula.

PHYSIOTHERAPY IN THE CONTEXT OF WOMEN’S HEALTH

The physiotherapist’s scope is broad, and they bring value as an integral member of the healthcare team. This may be in the context of fistula care exclusively, in the broader context of gynecologic and obstetric care, or in general musculoskeletal, neurological, and/or cardiopulmonary health. Physiotherapists can work across a spectrum from wellness and prevention services, to treatment of an acute injury, to working with those who now must live with a permanent disability.

Skilled physiotherapists optimize the function of healthy tissues. For example, in the context of prenatal care, they can work to improve the function of the pelvic and abdominal muscles and address spinal, hip, and pelvic mobility to facilitate a better labor experience. They may also teach new mothers to rehabilitate their own bodies after childbirth to improve strength, restore function, and prevent injury.

Skilled physiotherapists also treat acute and chronic injuries. In the case of pelvic floor fistula, there are varying degrees of tissue damage, from mild tissue damage to complete destruction of the pelvic tissues – nerves, muscles, organs, and connective tissues. In these cases, the physiotherapist can work to restore full or partial function, or she may offer alternative movement strategies to compensate for impaired muscle, joint, or tissue function.

In considering an individual with a severe disability, a physiotherapy plan of care may reduce this burden and improve function and quality of life. Disability management might include teaching compensatory movement strategies, training on the use of assistive devices, or working with families and caregivers, so that they may learn the best methods for facilitating independence and promoting inclusion in family and community life.

Keyser et al. described the disability status of women with fistula in Rwanda and eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo.12 Using the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS 2.0), they found that the burden of disability was high, comparable to that of individuals after a stroke. Domains most affected were the ability to perform life activities and participate in society. Importantly, the disability burden varied according to fistula type, lending support to the broad needs of women with fistula and the ability of skilled physiotherapy services to meet these needs. In a separate study design, Roa and colleagues described the physical and psychological sequalae of prolonged obstructed labor (POL), the leading cause of obstetric fistula. They found that the burden of disability was high, at 38% more than previous reports.13

Additionally, Keyser et al. published a systematic review of rehabilitative care practices for women with fistula.14 The authors determined that the evidence supports feasibility of implementing rehabilitative care practices and strong interest among stakeholders to do so. Their work notes that further research is necessary to establish efficacy for specific, impairment-based interventions due to the paucity of data and resources dedicated to physiotherapy and other rehabilitative care for women with fistula.

PERI-OPERATIVE PHYSIOTHERAPY FOR WOMEN WITH FISTULA

Even though a skilled surgeon can repair the fistula, damage to the pelvic muscles, nerves, and connective tissues also requires rehabilitation to achieve full or partial recovery of function. This is why physiotherapy or physiotherapy-informed care can be so important before and after fistula surgery. There are several common impairments observed among women with fistula that may specifically warrant physiotherapy involvement. Research supports the use of physiotherapy services to address the various complications described below and suggests that investment in physiotherapy program development will yield meaningful improvements in the burden of disability.15,16,17,18,19,20

Common impairments

Incontinence

Women may continue to have incontinence even after the fistula is repaired. Research shows that 15–33% of women report post-operative incontinence at the time of their hospital discharge. It is estimated that 12–31% of women with fistula will require more than one fistula surgery in their lifetime.21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28 Research also shows that continence rates decline over time, and a range of 45–100% of cases may become incontinent in the years following their fistula repair.29,30,31,32,33 We do not yet know all of the factors that contribute to incontinence after a fistula repair, but some studies suggest that the presence of scar tissue – fibrosis of the abdominal wall and pelvis and vaginal stenosis – are strongly associated with post-operative incontinence.23,34,35,36 In separate publications, Nardos et al. have reported on persistent urinary incontinence after fistula closure in Ethiopian and Ugandan populations. They found in both groups that women with persistent urinary incontinence were more likely to have acquired their fistula at an earlier age and with their first vaginal delivery. In both groups, stress and urgency urinary incontinence were common and symptoms were moderate to severe with significant negative impacts on mental health and quality of life.37,38

Pelvic pain

Pelvic pain can include pain or discomfort in the abdomen, pelvis, hips and/or low back. It may be present with physical activities, such as walking, carrying, or lifting, or occur with urination, bowel movements, sexual stimulation, or intercourse.

There is little research on pelvic pain among women with fistula. It has been reported that women who have experienced sexual violence are more likely to report pelvic pain, and rates of sexual violence are high in some regions where fistula is also common, such as in the Democratic Republic of Congo.39 It is important to understand the circumstances in which women develop fistula, so that a program of physiotherapy and rehabilitation can address some of these additional concerns, as well.

Sexual function

Sexual function is complex, and includes factors such as desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain. Research on the sexual function of women with fistula is limited, though this has become a growing area of interest and concern among health workers and women, alike. Recent studies suggest that women who have been repaired are more likely to complain of pain with intercourse (dyspareunia) and/or loss of desire. Many women also have problems achieving vaginal penetration due to stenosis and a shortened vagina.40,41,42,43,44,45,46

Musculoskeletal problems

Musculoskeletal problems can include limitations in joint range of motion of the hips, knees, and/or ankles, muscle weakness, impaired sensation and pain. These may lead to mobility problems, such as difficulty walking and performing daily activities. Research on musculoskeletal and mobility problems among women with fistula is also limited. Some studies show that 20–30% of women may experience foot drop, due to nerve damage and resulting leg weakness. Weakness and decreased range of motion at the knee and ankle may be more common among women with fistula, and they are also more likely to report difficulty walking.47

Treatment considerations

Pelvic floor exercise

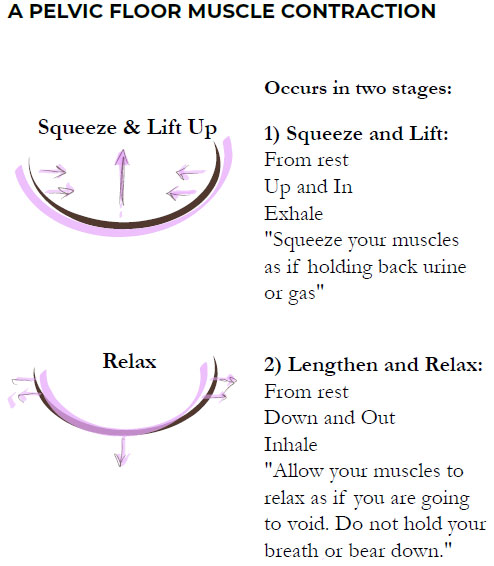

A large body of literature has established pelvic floor muscle training as an effective rehabilitative intervention to treat urinary incontinence and other pelvic floor disorders.15,48,49 Pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) is a program of exercises to address the endurance, power, coordination and relaxation components of muscle performance as they relate to function.50 An example of pelvic floor muscle exercise instruction is described in Figure 2. PFMT is often described as a core component of physiotherapy and physiotherapy-informed care for women with fistula despite very limited literature to support this intervention for this population. As direct research is lacking in the population with fistula, evidence from non-fistula-related pelvic floor rehabilitation is used to inform approaches to rehabilitation of women with fistula.

Another key gap in the literature are descriptions of pelvic floor integrity and function among women with fistula. It is biologically plausible, presumed very likely, and observed anecdotally that women with fistula resulting from POL or other trauma have sustained structural musculoskeletal and/or neurological injuries to the pelvic floor. It has been documented by Roa and colleagues that POL commonly results in obstetric fistula, as well as incontinence and pelvic pain.13 It is possible that in contrast, pelvic floor muscle function and integrity is wholly intact among women who have a cesarean birth-related iatrogenic fistula in conjunction with their first childbirth. It is recommended that clinicians keep this in mind when evaluating patients, designing interventions, and designing and conducting research.

2

A pelvic floor muscle contraction. From Keyser and McKinney, 2019,11 with permission.

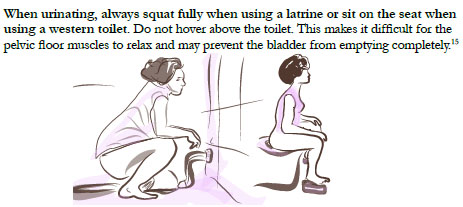

Health education

Health education is another key component of physiotherapy care, especially for women with fistula who may benefit from greater understanding of typical anatomy, physiology, and function, along with their injury, and how to accommodate, adapt, and optimize recovery. Anatomic models and illustrations are useful aids, as are written resources when literacy is not a barrier. Appendix 1 contains several images that have been developed for these purposes and have been used by physiotherapists for patient-focused health education. A sample that addresses toileting is found as Figure 3.

3

Health bladder habits. From Keyser and McKinney, 2019,11 with permission.

Manual therapy and massage techniques

Manual therapy and massage techniques may be used when providing 1 : 1 clinical care. These techniques are utilized to improve tissue mobility, generally, including muscles, and the tissue of and around areas of scarring/fibrosis. These techniques may be applied by a physiotherapist or other trained clinicians, and they may also be taught to the patient, so that she can help herself to move and feel better. It is important to consider the stages of tissue healing when applying these techniques. An incision must be closed and healed before using any aggressive massage techniques. These techniques may be helpful for women who have had a cesarean section, episiotomy, or other perineal incision or tearing, and any abdominal or pelvic scarring related to surgery or fistula.

Cardiovascular exercise

Aerobic exercise is an important part of recovery from surgery. In addition to being important for overall mental and physical health and wellness, aerobic exercise helps to promote improved healing after surgery. Aerobic exercise includes any exercise that increases the heart rate and respiratory rate. Examples of aerobic exercise include walking, running, biking, dancing, and swimming.

These types of exercise have been shown to improve outcomes after major surgeries, including abdominal and pelvic surgeries.51,52 For example, exercise can decrease risk of complications such as blood clots and breathing problems, which can develop after a major surgery.51 Aerobic exercise prevents weakness and a decline in mobility after surgery, which contributes to improved patient outcomes.51,53 In fact, research shows that patients who participate in aerobic exercise after a major surgery have more successful surgeries, better post-operative health outcomes and are less likely to need additional surgeries or medical procedures.52 Multiple studies have shown that having a planned exercise program for patients to follow after surgery helps them to be more active and spend less time sitting.51,52,53 Because sitting can decrease blood flow to the pelvis and impair healing, it is especially important for patients to reduce time spent sitting after pelvic surgery.

THE INTERNATIONAL CLASSIFICATION OF FUNCTION, DISABILITY, AND HEALTH: A TOOL TO GUIDE PHYSIOTHERAPY FOR WOMEN WITH FISTULA

Using the ICF to plan for rehabilitative care:

Why is it important to think about function and disability when we care for women with pelvic floor fistula and other reproductive health conditions? Each woman is affected a little bit differently depending on many factors – not just the health condition itself.

For each impairment, activity limitation and participation restriction, we must ask the individual both whether she experiences these issues, and also the extent to which this impacts her life (severity). One useful tool to broadly determine the impact of a health condition, such as fistula, on a woman’s daily life is called the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS 2.0).54 This tool is a simple survey that provides information about the level of disability a person experiences as a result of a health condition. It provides a score that represents a measure of disability.

This tool can be used before and after an intervention to determine how effective or useful the intervention is in improving a person’s health. It has been translated into many languages and validated for use in a variety of populations, including post-surgical.54

Below is a description of each element of the ICF framework that is shown in Figure 1, with examples of how this may apply to a woman with fistula.10

Health Condition | Example |

Any disease, illness, injury, or disorder that influences functioning and may lead to disability. | Ex. Obstetric fistula |

Function/Disability | Example |

Impairments in Body Structures and Functions The extent of damage to body structures or the severity to which body functions are impacted by the health condition Activity Limitations Actions and tasks executed by individuals Participation Restrictions Involvement in life situations | Bladder, vagina, pelvic floor muscles, urinary system, digestive system (anus, rectum), reproductive system, sexual function Inability to maintain personal hygiene; interrupted due to frequent toileting and clothing changes; inability to engage in sexual activity Marital strain or divorce, isolation from family and community activities |

Contextual Factors (positive or negative influences) | Example |

Personal Gender, age, ethnicity, tribal affiliation, habits, lifestyle, education, profession Environmental Physical, social, attitudinal environment may be a barrier or facilitator | A young woman with no children may be more impacted by fistula than an older woman who has surviving children at the time she developed fistula Community beliefs about fistula; family support; access to a health facility. |

Promoting woman-centered care using the ICF

The primary aim of fistula surgery is to close the hole and restore continence, so that the woman with fistula does not leak urine or stool continuously. The primary goal of physiotherapy and rehabilitation is to identify physical factors, such as muscle weakness, incoordination, and decreased flexibility and how these impact a woman’s ability to function in daily life. Rehabilitation requires that we ask a woman about what she can and cannot do for herself, her family or her community and about her personal goals for treatment. We might ask her the following:

What does success look like for you? How will you know that you are better? What self-care activities, family roles, or community responsibilities would you like to be able to do that you currently have difficulty with or cannot do?

Her answers to these questions help to guide physiotherapy treatment and will help both the patient and the healthcare worker to know when treatment has been successful.

Planning physiotherapy or physiotherapy-informed care

It is important to remember that physiotherapy and rehabilitation treatment techniques address functional problems. They do not directly address the fistula or the underlying cause of disease. Some physiotherapy treatment techniques include the following:

- Pelvic floor muscle exercises to improve strength, function, and coordination of injured or weak muscles.

- Stretching exercises to improve muscle flexibility and mobility of the hips, pelvis, and back.

- Functional exercises to enable independent movement to accomplish self-care and daily tasks.

- Manual therapy or massage techniques to improve tissue mobility and function, including scar massage.

- Patient education about pelvic floor anatomy and function, bladder training, fluid schedule, and hydration.

- Accommodations for persistent disability, including incontinence management with absorbent underwear or pads, assistive devices for mobility (walkers, crutches, wheelchairs, etc.), and other adaptive equipment as needed.

CONCLUSION

A thoughtful approach to rehabilitation can empower women to seek and understand health-related information and to take action for health – for herself, her family, and her community.55 This contributes to restoring a woman’s sense of agency – her sense that she has control over her own body and what happens to it.56 This can be particularly important for women who have experienced the physical and psychological trauma that accompanies an obstructed labor experience, stillbirth, unpleasant, or unwanted medical procedures at traditional or ill-equipped health clinics, forced sex or marriage, among others.

The ICF framework aids healthcare workers in identifying the factors that contribute to a woman’s health and well-being beyond her medical diagnosis. We recommend using this framework to guide physiotherapy and rehabilitation treatment for any woman participating in healthcare related to her fistula. By identifying specific physical impairments and functional limitations, treatment may be tailored to address the unique needs and health goals of each woman.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- Women who present with fistula may also have tissue damage and functional impairments beyond those of the fistula itself. Physiotherapy interventions can address these concerns.

- Pre-operative and short- and long-term rehabilitation should focus on the whole woman, evaluating and treating according to her needs regarding continence, sexual health, pain, mobility, and other functional domains.

- Evaluation of disability and function, especially with validated tools such as the WHODAS 2.0, can help document baseline status and change over time.

- Specific pelvic floor muscle exercise may be useful and is recommended, especially in the absence of specialty-trained physiotherapists who are competent in pelvic floor muscle assessment and treatment.

- Exercises targeting flexibility, strength, balance, and coordination for the full body and emphasizing the trunk, pelvis, and hips are nearly universally acceptable.

- Where staffing and resources are most limited, physiotherapy-informed care may be carried out by other health professionals and staff and may be performed in group settings to maximize access.

- Physiotherapy has been under resourced in all settings, especially in settings where obstetric fistula is most common. As such, research is lacking. Research of all types is recommended to be completed in this field.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Author(s) statement awaited.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

APPENDIX

Implementing Physical Rehabilitation Services into Comprehensive Fistula and Maternity Care: A Training Guide for Health Care Workers

REFERENCES

Howard-Wilsher S, Irvine L, Fan H, et al. Systematic overview of economic evaluations of health-related rehabilitation. Disabil Health J 2016;9(1):11–25. | |

Physiotherapy W. What is physiotherapy? [Internet]. Available from: https://world.physio/resources/what-is-physiotherapy. | |

Cieza A, Causey K, Kamenov K, et al. Global estimates of the need for rehabilitation based on the Global Burden of Disease study 2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet [Internet] 2020;396(10267):2006–17. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32340-0. | |

Gupta N, Castillo-Laborde C, Landry MD. Health-related rehabilitation services: assessing the global supply of and need for human resources. BMC Health Serv Res [Internet] 2011;11(1):276. Available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/11/276. | |

Howard-Wilsher S, Irvine L, Fan H, et al. Systematic overview of economic evaluations of health-related rehabilitation. Disabil Health J [Internet] 2015;9(1):11–25. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1936657415001508. | |

Jesus TS, Koh G, Landry M, et al. Finding the “Right-Size” Physical Therapy Workforce: International Perspective Across 4 Countries. Phys Ther 2016;96(10):1597–609. | |

Jesus TS, Landry MD, Dussault G, et al. Human resources for health (and rehabilitation): Six Rehab-Workforce Challenges for the century. Hum Resour Health [Internet] 2017;15(1):1–12. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12960-017-0182-7. | |

Jesus TS, Landry MD, Hoenig H, et al. Is Physical Rehabilitation Need Associated With the Rehabilitation Workforce Supply? An Ecological Study Across 35 High-Income Countries. Int J Heal policy Manag 2022;11(4):434–42. | |

Landry MD, Hack LM, Coulson E, et al. Workforce Projections 2010–2020: Annual Supply and Demand Forecasting Models for Physical Therapists Across the United States. Phys Ther 2016;96(1):71–80. | |

World Health Organization. Towards a Common Language for Functioning, Disability and Health ICF [Internet] International Classification. Geneva, 2002;1149;1–22. Available from: http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/training/icfbeginnersguide.pdf. | |

Keyser L, McKinney J. Implementing Physical Rehabilitation Services into Comprehensive Fistula and Maternity Care: A Training Guide for Health Workers. Mama LLC and EngenderHealth/Fistula Care Plus; 2019. www.themamas.world/trainingguide. | |

Keyser L, Myer ENB, McKinney J, et al. Function and disability status among women with fistula using WHODAS2.0: A descriptive study from Rwanda and Democratic Republic of Congo. Int J Gynecol Obstet 2021:1–6. | |

Roa L, Caddell L, Ganyaglo G, et al. Toward a complete estimate of physical and psychosocial morbidity from prolonged obstructed labour: a modelling study based on clinician survey. BMJ Glob Heal [Internet] 2020;5(7):2520. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002520. | |

Keyser L, McKinney J, Hosterman L, et al. Rehabilitative care practices in the management of childbirth-related pelvic fistula: A systematic review. Int Urogynecol J 2021;32(9):2311–24. | |

Hagen S, Stark D, Glazener C, et al. Individualised pelvic floor muscle training in women with pelvic organ prolapse (POPPY): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet [Internet] 2014;383(9919):796–806. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24290404. | |

Burgio KL. Update on behavioral and physical therapies for incontinence and overactive bladder: the role of pelvic floor muscle training. Curr Urol Rep 2013;14(5):457–64. | |

Castille Y-J, Avocetien C, Zaongo D, et al. Impact of a program of physiotherapy and health education on the outcome of obstetric fistula surgery. Int J Gynecol Obstet 2014;124(1):77–80. | |

Castille YJ, Avocetien C, Zaongo D, et al. One-year follow-up of women who participated in a physiotherapy and health education program before and after obstetric fistula surgery. Int J Gynecol Obstet [Internet] 2015;128(3):264–6. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2014.09.028. | |

Keyser L, McKinney J, Salmon C, et al. Analysis of a pilot program to implement physical therapy for women with gynecologic fistula in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Int J Gynecol Obstet 2014;127(2):127–31. | |

Wolf JK. Prevention and treatment of vaginal stenosis resulting from pelvic radiation therapy. Community Oncol 2006;3(10):665–71. | |

Wall LL, Arrowsmith SD, Briggs ND, et al. The obstetric vesicovaginal fistula in the developing world. Obstet Gynecol Surv 2005;60(7 Suppl 1):S51. | |

Wall LL, Karshima JA, Kirschner C, et al. The obstetric vesicovaginal fistula: characteristics of 899 patients from Jos, Nigeria. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004;190(4):1011–6. | |

Nardos R, Browning A, Chen CCG. Risk factors that predict failure after vaginal repair of obstetric vesicovaginal fistulae. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009;200(5):578. e4. | |

Onsrud M, Sjoveian S, Mukwege D. Cesarean delivery-related fistulae in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2011;114(1):10–4. | |

Holme A, Breen M, MacArthur C. Obstetric fistulae: a study of women managed at the Monze Mission Hospital, Zambia. BJOG An Int J Obstet Gynaecol 2007;114(8):1010–7. | |

Tebeu P, Fomulu J, Mbassi A, et al. Quality care in vesico-vaginal obstetric fistula: case series report from the regional hospital of Maroua-Cameroon. Pan Afr Med J 2010;5(1). | |

Kirschner CV, Yost KJ, Du H, et al. Obstetric fistula: the ECWA Evangel VVF Center surgical experience from Jos, Nigeria. Int Urogynecol J 2010;21(12):1525–33. | |

Ghosh TS, Kwawukume EY. A new method of achieving total continence in vesico-urethro-vaginal fistula (circumferential fistula) with total urethral destruction–surgical technique. West Afr J Med 1993;12(3):141–3. | |

Drew LB, Wilkinson JP, Nundwe W, et al. Long-term outcomes for women after obstetric fistula repair in Lilongwe, Malawi: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016;16(1):1. | |

Barone MA, Frajzyngier V, Ruminjo J, et al. Determinants of postoperative outcomes of female genital fistula repair surgery. Obstet Gynecol 2012;120(3):524–31. | |

McFadden E, Taleski SJ, Bocking A, et al. Retrospective review of predisposing factors and surgical outcomes in obstetric fistula patients at a single teaching hospital in Western Kenya. J Obstet Gynaecol Canada 2011;33(1):30–5. | |

Murray C, Goh JT, Fynes M, et al. Urinary and faecal incontinence following delayed primary repair of obstetric genital fistula. BJOG An Int J Obstet Gynaecol 2002;109(7):828–32. | |

Browning A. Prevention of residual urinary incontinence following successful repair of obstetric vesico‐vaginal fistula using a fibro‐muscular sling. BJOG An Int J Obstet Gynaecol 2004;111(4):357–61. | |

Roenneburg ML, Genadry R, Wheeless CR. Repair of obstetric vesicovaginal fistulas in Africa. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006;195(6):1748–52. | |

Goh JTW, Browning A, Berhan B, et al. Predicting the risk of failure of closure of obstetric fistula and residual urinary incontinence using a classification system. Int Urogynecol J 2008;19(12):1659–62. | |

Loposso M, Hakim L, Ndundu J, et al. Predictors of recurrence and successful treatment following obstetric fistula surgery. Urology 2016;97:80–5. | |

Nardos R, Phoutrides EK, Jacobson L, et al. Characteristics of persistent urinary incontinence after successful fistula closure in Ethiopian women. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-020-04265-w. | |

Nardos R, Jacobson L, Garg B, et al. Characterizing Persistent Urinary Incontinence After Successful Fistula Closure: The Uganda Experience. Am J Obstet Gynecol [Internet] 2022. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2022.03.008. | |

Dossa NI, Zunzunegui MV, Hatem M, et al. Fistula and Other Adverse Reproductive Health Outcomes among Women Victims of Conflict‐Related Sexual Violence: A Population‐Based Cross‐Sectional Study. Birth 2014;41(1):5–13. | |

Turan JM, Johnson K, Polan ML. Experiences of women seeking medical care for obstetric fistula in Eritrea: Implications for prevention, treatment, and social reintegration. Glob Public Health 2007;2(1):64–77. | |

Ankaku AS, Lengmang SJ, Mikah S, et al. Sexual life among Nigerian women following successful fistula repair. Int J Gynecol Obstet 2017;137(1):67–71. | |

Amisi CN, Luendo M. International Society of Obstetric Fistula Surgeons. In: Les défis que rencontrent les femmes réparées des FUG-DB: Cas de Kongolo et Kabalo en RDC (Challenges faced by women repaired by FUG-DB: Case of Kongolo and Kabalo in the DRC; research from Panzi hospital staff, Bukavu, DRC). 2016. | |

Bukabau BR. International Society of Obstetric Fistula Surgeons. In: Impact de le fistule sur la vie sexuelle des femmes – Hôpital Saint Joseph, Kinshasa, Démocratique République du Congo (The impact of fistula on women’s sexual life; research from St Joseph’s Hospital, Kinshasa, DRC). 2016. | |

Esegbona G, Isa M. Learning from the 1st Obstetric Fistula Patients Conference – How to Improve Quality of Care. Int J Gynecol Obstet 2015;131(Suppl 5):E157. | |

Pope R, Ganesh P, Chalamanda C, et al. Sexual Function Before and After Vesicovaginal Fistula Repair. J Sex Med 2018;15(8):1125–32. | |

Anzaku S, Lengmang S, Mikah S, et al. Sexual activity among Nigerian women following successful obstetric fistula repair. Int J Gynaecol Obs 2017;137(1):67–71. | |

Tennfjord MK, Muleta M, Kiserud T. Musculoskeletal sequelae in patients with obstetric fistula – a case-control study. BMC Womens Health [Internet] 2014;14:136. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=4228064&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. | |

Dumoulin C, Cacciari L, Hay-smith EJC. Pelvic floor muscle training versus no treatment , or inactive control treatments , for urinary incontinence in women ( Review ). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;(10). | |

Dumoulin C, Morin M, Danieli C, et al. Group-Based vs. Individual Pelvic Floor Muscle Training to Treat Urinary Incontinence in Older Women: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med 2020;180(10):1284–93. | |

Bo K, Frawley HC, Haylen BT, et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for the conservative and nonpharmacological management of female pelvic floor dysfunction. Neurourol Urodyn 2017;36(2):221–44. | |

O’Doherty AF, West M, Jack S, Grocott MPW. Preoperative aerobic exercise training in elective intra-cavity surgery: a systematic review. Br J Anaesth 2013;110(5):679–89. | |

Hoogeboom TJ, Dronkers JJ, Hulzebos EHJ, et al. Merits of exercise therapy before and after major surgery. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2014;27(2):161–6. | |

Rendi M, Szabo A, Szabó T, et al. Acute psychological benefits of aerobic exercise: a field study into the effects of exercise characteristics. Psychol Health Med 2008;13(2):180–4. | |

WHO Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS 2.0) [Internet]. Available from: http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/more_whodas/en/. | |

Paterick, Timothy.; Patel, Nachiket.; Tajik, Jamil. and Chandrasekaran K. Improving health outcomes through patient education and partnerships with patients. Proc (Baylor Univ Med Centre) [Internet]. 2017;30(1):112–3. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5242136/pdf/bumc0030-0112.pdf. | |

Moore JW. What is the sense of agency and why does it matter? Front Psychol 2016;7:1–9. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards programme CLICK HERE)