This chapter should be cited as follows:

Wilson C, Peters L, et al., Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.409363

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Obstetrics Module

Volume 7

Maternal mental health in pregnancy

Volume Editor: Professor Louise Howard, King’s College, London, UK

Chapter

Substance Misuse in Pregnancy

First published: February 2021

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

INTRODUCTION

Substance misuse refers to the harmful or hazardous use of psychoactive substances, including alcohol and nicotine. Psychoactive substances are defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as those which affect mental processes, including cognition and affect.1 Psychoactive substance misuse is associated with adverse physical, psychological and social outcomes. Repeated use of such substances can at times lead to dependence syndrome, although the term ‘psychoactive’ does not imply that the drug will produce dependence. Similarly, the term ‘substance misuse’ does not always imply dependence. Dependence is characterized by a strong desire to take the substance, difficulty in controlling its use, persistence in use despite knowledge of potential harms, neglect of activities other than using the substance and sometimes physical withdrawal symptoms.2 Globally, harmful use of alcohol results in 3.3 million deaths annually and at least 15.3 million people have drug use disorders.1

Similarly, substance misuse during pregnancy may increase the risk of adverse maternal and child sequelae. These include reduced engagement with antenatal care3 and obstetric and neonatal complications such as low birth weight and prematurity.4,5 Estimating the prevalence of substance misuse during pregnancy is often difficult, perhaps due to reluctance by health professionals to enquire about it or women to disclose it. However, in an analysis of maternal deaths in the UK between 2009 and 2013, substance misuse was one of the leading factors associated with increased odds of maternal death (adjusted odds ratio of 12).6 Substance misuse and mental disorder are often co-morbid and a systematic review of prevalence for postpartum depression in a population of women misusing substances suggests a higher prevalence than in the general pregnant population.7 Substance misuse in either partner within a relationship is also a well-established risk factor for domestic violence.8 Clearly studying longer-term outcomes in offspring is challenging, with small sample sizes and unmeasured confounding factors characteristic of many of the studies in this area. Despite this there is some evidence from prospective, longitudinal birth cohorts that maternal substance misuse is associated with a range of emotional and behavioral difficulties in exposed children5 and even in a recent US cohort with future substance misuse at age 30.9

Pregnancy may be a motivator for some women to reduce or stop substance misuse.10 Certainly prevalence estimates from the US would suggest a lower prevalence of substance misuse in women during pregnancy (around 4%) than among non-pregnant, reproductive age women (10%).11 Moreover, for many women who misuse substances, pregnancy may be the first time that they have engaged with health services. As such, it provides an opportunity for health services to support women and their wider social networks with their substance misuse. There is evidence that engagement in a drug treatment program during pregnancy results in improvements in antenatal care and general health of both mother and baby, regardless of whether abstinence is achieved.4 As a result, the UK Department of Health, in their clinical guidelines on drug misuse and dependence (last updated in 2017), recommend that pregnant women seeking to engage in treatment of their substance misuse be fast-tracked into a treatment program as early in pregnancy as possible.12

GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF MANAGEMENT

An overview of substances misused, effects of intoxication and effects of withdrawal are provided in Table 1. WHO provide a number of recommendations for the identification and management of substance misuse in pregnancy across six areas: (1) screening and brief intervention, (2) psychosocial interventions, (3) detoxification, (4) dependence management, (5) infant feeding, and (6) management of neonatal withdrawal (see Box 1).13 The guidelines emphasize the importance of routine enquiry about substance misuse of all pregnant women at all antenatal visits, given that women may not always feel comfortable with disclosure.13 Brief interventions early in pregnancy are also advised.13 Brief interventions are short structured therapies, usually a maximum of 30 minutes in duration designed to be delivered by non-specialists such as primary care professionals, to encourage behavior change.

1

Summary of common substances of misuse.

Substance | Effect of intoxication | Effect of withdrawal |

Alcohol | Disinhibition, confusion, drowsiness or coma, nausea and vomiting, ataxia | Tremor, anxiety, sweating, palpitations, nausea and vomiting, seizures (life threatening) |

Benzodiazepines | Slurred speech, unsteadiness, nystagmus, drowsiness or coma, impaired judgment, attention and memory | Seizures (life threatening), anxiety, psychomotor agitation, tremor, nausea and vomiting, insomnia |

Cannabis | Conjunctival injection, hyperphagia, euphoria, dry mouth, depersonalization, derealization, paranoid ideas, heightened perceptual sensitivity | Irritability, insomnia, anorexia (but physical withdrawal symptoms are uncommon) |

Opioids | Pupillary constriction, psychomotor agitation or retardation, slurred speech, drowsiness or coma | Pupillary dilatation, nausea and vomiting, myalgia, lacrimation, rhinorrhoea, piloerection, sweating, diarrhea, insomnia |

Stimulants | Pupillary dilatation, euphoria, sweating, nausea and vomiting, increased sociability, psychomotor retardation or agitation | Hypersomnia, fatigue, anhedonia, depression, anxiety |

Box 1 WHO recommendations on identification of substance use disorders in pregnancy

- Healthcare providers should ask all pregnant women about their use of alcohol and other substances (past and present) as early as possible in the pregnancy and at every antenatal visit.

- Healthcare providers should offer a brief intervention to all pregnant women using alcohol or drugs.

- Healthcare providers managing pregnant or postpartum women with alcohol or other substance use disorders should offer comprehensive assessment and individualized care.

- Healthcare providers should at the earliest opportunity advise pregnant women dependent on alcohol or drugs to cease their alcohol or drug use and offer, or refer to, detoxification services under medical supervision where necessary and applicable.

- Pregnant women dependent on opioids should be encouraged to use opioid maintenance treatment whenever available rather than to attempt opioid detoxification.

- Pregnant women with benzodiazepine dependence should undergo a gradual dose reduction, using long-acting benzodiazepines.

- Pregnant women who develop withdrawal symptoms following the cessation of alcohol consumption should be managed with the short-term use of a long-acting benzodiazepine.

- In withdrawal management for pregnant women with stimulant dependence, psychopharmacological medications may be useful to assist with symptoms of psychiatric disorders but are not routinely required.

- Pharmacotherapy is not recommended for routine treatment of dependence on amphetamine-type stimulants, cannabis, cocaine, or volatile agents in pregnant patients.

- Given that the safety and efficacy of medications for the treatment of alcohol dependence has not been established in pregnancy, an individual risk-benefit analysis should be conducted for each woman.

- Pregnant patients with opioid dependence should be advised to continue or commence opioid maintenance therapy with either methadone or buprenorphine.

- Mothers with substance use disorders should be encouraged to breastfeed unless the risks clearly outweigh the benefits.

- Breastfeeding women using alcohol or drugs should be advised and supported to cease alcohol or drug use; however, substance use is not necessarily a contraindication to breastfeeding.

- Skin-to-skin contact is important regardless of feeding choice and needs to be actively encouraged for the mother with a substance use disorder who is able to respond to her baby’s needs.

- Mothers who are stable on opioid maintenance treatment with either methadone or buprenorphine should be encouraged to breastfeed unless the risks clearly outweigh the benefits.

- Healthcare facilities providing obstetric care should have a protocol in place for identifying, assessing, monitoring and intervening, using non-pharmacological and pharmacological methods, for neonates prenatally exposed to opioids.

- An opioid should be used as initial treatment for an infant with neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome if required.

- If an infant has signs of a neonatal withdrawal syndrome due to withdrawal from sedatives or alcohol, or the substance the infant was exposed to is unknown, then phenobarbital may be a preferable initial treatment option.

- All infants born to women with alcohol use disorders should be assessed for signs of fetal alcohol syndrome.

A recommendation common to many of the guidelines on substance misuse in pregnancy12,13,14,15 is the need for information sharing between agencies and a coordinated approach to care, in order to devise a care plan which considers needs, risks, goals and wider social networks. Where available, disciplines that may be involved in care include maternity, primary care, addictions, social care and psychiatric services. This is in recognition of the fact that often there will be multiple physical and mental health needs and social stressors. Risks to the mother, her unborn child and other children in the family should always be considered and safeguarding referrals made when felt to be appropriate. Management involves a range of approaches, both psychosocial and pharmacological. Regarding prescribing, the aim of care is to achieve stability; as with all prescribing in pregnancy, a balance must be struck between minimizing exposure of the fetus to prescribed medication or illicit drugs versus a potential increase in relapse risk if prescribed substitutes are withdrawn.12

Women and their families will likely require ongoing support in the postpartum, including management of co-morbid mental disorders and social support, particularly around parenting. Currently UK Department of Health guidelines recommend that breastfeeding be encouraged, even in women who continue to misuse substances, except in those using cocaine or crack cocaine or high doses of benzodiazepines.12 It may even reduce the intensity and length of neonatal abstinence syndrome.4 Similarly, it is encouraged by WHO unless the risks clearly outweigh the benefits.13

ALCOHOL

The global prevalence of alcohol use during pregnancy is estimated to be 9.8%.16 Whether there is a safe level of alcohol consumption in pregnancy is unclear. Heavy drinking (68 g or more per week) and binge drinking (50 g or more on one occasion) in pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of prematurity, low birth weight, small for gestational age infants17,18 and developmental delays, known as fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (see Box 2). While it is often difficult to isolate the effect of alcohol from other associated adversities such as co-morbid substance misuse and social stressors, there does appear to be a dose-response relationship for small for gestational age and low birth weight when alcohol consumption is above 10 g/day and for prematurity when alcohol intake is above 18 g/day.19 The association between lower levels of alcohol consumption (less than 32 g/week) and adverse outcomes is less clear.20 Given this, current advice from both the UK and Australian Departments of Health and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is that the safest option is to abstain completely from alcohol in pregnancy.21,22,23

Box 2 FASD are a group of conditions that occur in children exposed to alcohol during pregnancy. The clinical features of each condition are outlined below:

Fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS)

- Intellectual disabilities

- Attention deficits and hyperactivity

- Language, memory and executive function deficits

- Small head

- Poor growth

- Distinctive facial features: short palpebral fissures, a thin upper lip vermillion and a smooth philtrum

The phenotypes of the other three FASD conditions is less well defined:

Partial fetal alcohol syndrome (PFAS)

- Minor facial anomalies

- Intellectual disabilities and developmental delays

- Hyperactivity with attention deficit and impulsivity

Alcohol related neuro-developmental disorder (ARND)

- Absence of growth and facial anomalies

- Prominent neurocognitive deficits

Alcohol related birth defects (ARBD)

- Lack most facial anomalies

- Prominent behavioral disturbance or congenital structural abnormalities

Neonates exposed to alcohol in pregnancy may experience a withdrawal syndrome. If there has been known heavy exposure to alcohol and there are signs of withdrawal or an infant is experiencing withdrawal symptoms in the absence of known opioid exposure, WHO guidelines recommend the use of phenobarbital as an initial treatment option.13 Regarding breastfeeding, while alcohol use is not a complete contraindication, WHO guidelines recommend a careful consideration of risks and benefits and advise that in cases of heavy alcohol consumption, for example in alcohol dependence, breastfeeding exposes the infant to high risks which could be avoided if safe breast milk alternatives are available. They also suggest that it is possible to reduce exposure in women using alcohol intermittently by avoiding breastfeeding 2 hours after consuming one standard drink or 4–8 hours after consuming more than one drink in a single occasion.13

Pharmacological interventions

WHO recommend that pregnant women dependent on alcohol should be encouraged to cease their alcohol use and, if necessary, referred to a service that can support detoxification at the earliest opportunity.13 They should be advised against stopping drinking suddenly due to the life-threatening complications of alcohol withdrawal, such as seizures and delirium tremens and chlordiazepoxide or diazepam should be used to prevent these (see section on ‘benzodiazepines’). Detoxification should ideally be in the inpatient setting to facilitate close monitoring and liaison between obstetric and addictions teams.14 There are insufficient data on safety to support the use of relapse prevention medications such as acamprosate, disulfiram and naltrexone.14 However, clearly the risks of relapse to alcohol use versus maintaining abstinence with the help of a relapse prevention medication need to be weighed for each individual. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines recommend that women be supported to reduce their alcohol intake even if they decline assisted alcohol withdrawal.24

Psychosocial interventions

UK Department of Health guidelines advise that pregnant women using alcohol should be offered brief, or if necessary more extended, interventions to completely stop or reduce their alcohol consumption.12 There is also some limited evidence that a brief intervention of 10–15 minutes of scripted counselling by a nutritionist incorporating advice about how to reduce consumption and feedback may increase abstinence.25 A systematic review of randomized controlled trials of psychoeducational interventions to reduce alcohol consumption in women during pregnancy or who are planning a pregnancy yielded four studies. While some studies demonstrated improved rates of abstinence, results were inconsistent, with little evidence to support the use of one specific type of intervention.26

TOBACCO

The global prevalence of smoking during pregnancy is estimated to be 1.7% and is often co-morbid with mental disorder and other substance misuse.27 Smoking is clearly associated with a range of adverse outcomes for the offspring, with nicotine and carbon monoxide decreasing the fetal oxygen gradient and impeding nutrient transfer.28 It is associated with an increased risk of miscarriage.28 It is also associated with a range of obstetric complications including prematurity, placental abruption and stillbirth.28 There are adverse effects on fetal growth. At the extreme end, this can cause intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) and has also been shown to extend into childhood with children of smokers being shorter at the age of 5 compared to the children of non-smokers. This appears to be independent of exposure to environmental tobacco smoke in the children postpartum.29

There is strong evidence from a systematic review that smoking cessation programs improve rates of smoking cessation during pregnancy and in turn reduce rates of prematurity and low birth weight.29 NICE guidelines recommend that all pregnant women who are currently smoking or who have stopped in the last 2 weeks be referred to smoking cessation services.15 There are certain populations who may find it more difficult to stop smoking; for example there is evidence that women with mental disorders may find it more difficult to stop, even if they are referred to smoking cessation services,30 so other approaches which may support cessation could be considered, such as referral to mental health services. Regarding electronic cigarettes, WHO guidelines advise against their use in pregnancy due to their unknown safety profile.31 Regarding breastfeeding, while there is a little nicotine transferred to breast milk, benefits of breastfeeding likely outweigh the risks in mothers who smoke. Nonetheless, 50% of smokers report that smoking affected their breastfeeding decisions and 10% reported smoking being the reason for stopping breastfeeding.28

Pharmacological interventions

NICE guidelines recommend that nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) should only be considered if smoking cessation interventions without NRT have failed and there is complete smoking cessation.15 However, a systematic review of randomized controlled trials of NRT in pregnancy found insufficient evidence that it improved rates of smoking cessation or reduced risks of miscarriage, stillbirth, prematurity, low birth weight, admission to neonatal intensive care or neonatal death compared to control groups.32 The drugs bupropion and varenicline should not be prescribed to pregnant or breastfeeding women.14

Psychosocial interventions

Compared to other forms of substance misuse in pregnancy, there have been a number of studies investigating the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions for women who smoke during pregnancy. A systematic review of 86 trials of psychosocial smoking cessation interventions in pregnancy, when compared to usual care, found significant improvements in the proportion of women achieving smoking cessation and significant reductions in numbers of premature and low birth weight infants. Interventions involving peer social support, feedback, counselling and incentives were all effective.29

OPIOIDS

In a large US population-based retrospective cohort between 2012 and 2014, 2.3% of women had evidence of opioid misuse in the year prior to delivery.33 This may include misuse and/or dependence on both illicit opioids and opioids prescribed by a medical practitioner.

While there is a lack of evidence to support a direct association between fetal teratogenicity and opioid exposure, fluctuating levels in the maternal blood may lead to withdrawal or overdose in the fetus.34 Moreover, opioid misuse is associated with a number of risks such as injecting, other substance misuse, poor diet, neglect of personal care and poor engagement with obstetric services: all of which can adversely impact obstetric outcomes and indirectly cause harm to the developing infant. It is important for health professionals to enquire about these associated risks.

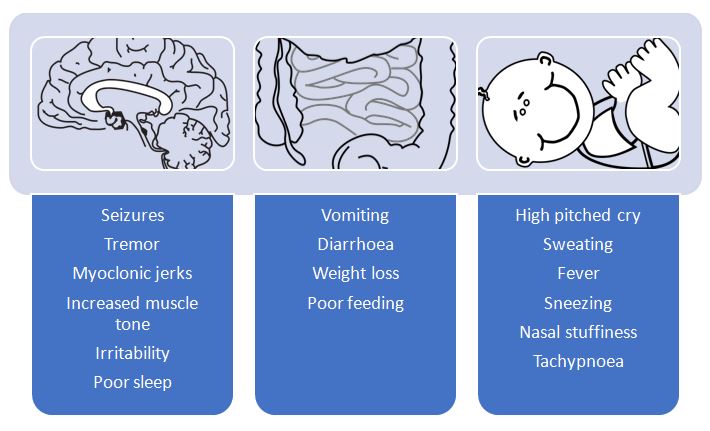

Neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) occurs in between 70 and 95% of the neonates of mothers who have misused opioids during pregnancy.34 Signs include a high-pitched cry, rapid breathing, ineffective sucking and excessive wakefulness35 (Figure 1 shows further signs and symptoms of NAS). Onset is between 24 and 48 hours following delivery, although can occur up to 10 days postpartum, particularly if the woman is taking methadone in conjunction with benzodiazepines.34 Evidence is conflicting as to whether there is a dose-response relationship between dose of opioid and severity of NAS; this will also be discussed later in the context of opioid substitution. As a result, WHO recommend that any neonate exposed to opioids in utero be assessed for signs of NAS and should remain in hospital for at least 4–7 days following birth for monitoring.13 Opioids are recommended for initial NAS treatment and phenobarbital if inadequate control of symptoms is achieved or concurrent use of other substances such as alcohol or benzodiazepines during pregnancy is suspected.13 Surveys of UK and US clinicians would suggest that the majority use morphine or methadone as treatment,36 although there is emerging evidence that buprenorphine may be associated with shorter duration of treatment and shorter hospital stay when compared to morphine.37

1

Clinical features of neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) following opioid exposure.

Pharmacological interventions

Methadone and buprenorphine are recommended in the non-pregnant population for the management of opioid dependence.38 WHO also recommend their use in the pregnant population at a dose that stops or minimizes illicit opioid use, with a focus on maintaining stability.13 Methadone maintenance treatment compared to heroin misuse is associated with a number of improved outcomes for mother and baby, including earlier antenatal care, reduced risk of prematurity39 and reduced risk of low birth weight.40

The metabolism of methadone is increased in the third trimester of pregnancy and it may occasionally be necessary to increase the dose or split it, from once-daily consumption to twice-daily consumption, or both.12 Split dosing may minimize fetal intoxication or withdrawal.41 Management of pain in labor should be discussed with the woman and obstetric team.14 The delivery method should be agreed upon during antenatal care and the obstetric team made aware of the patient’s opioid dependence.34

The choice of buprenorphine versus methadone should be individualized to the patient and switching during pregnancy, particularly if well maintained, is discouraged.13 There have been a number of studies comparing methadone and buprenorphine in pregnancy. Both appear to be associated with NAS, although an international randomized controlled trial comparing the two suggests that NAS may be less severe with buprenorphine,42 with buprenorphine exposed neonates requiring significantly less morphine, a shorter hospital stay and a shorter duration of treatment for NAS than methadone exposed neonates. However, a subsequent systematic review which also included this study indicated that methadone may be associated with better retention in treatment.43 Another systematic review found a higher birth weight and lower risk of prematurity in neonates exposed to buprenorphine versus methadone.44 Moreover, a recent study utilizing two population-level cohorts in Norway and the Czech Republic found slightly fewer adverse neonatal outcomes, including NAS and small for gestational age neonates with buprenorphine compared to methadone, although these results were not statistically significant.45

There is inconsistent evidence that dose of methadone is associated with severity of NAS.46 While one study demonstrated no association,47 another did show significantly increased odds of receiving pharamacological treatment for NAS when the mother used 90 mg or more of methadone versus 1–29 mg.48 Thus the WHO recommendation that all neonates exposed to opioids during pregnancy be assessed for signs of NAS, regardless of level of exposure, also applies to neonates exposed to opioid substitutes such as methadone and buprenorphine.13

Most guidelines13,14 are clear that opioid detoxification should generally be avoided during pregnancy, as relapse rates are high and risks are greater from failed detoxification and relapse to illicit drug use than from opioid maintenance treatment. Low rates of detoxification completion and high rates of relapse were also found in a recent systematic review.49 However, the UK Department of Health has issued guidance for detoxification in women who are particularly stable and keen to pursue detoxification. They advise that there should be a focus on stabilization in the first trimester due to an increased risk of spontaneous abortion with detoxification during this time. Detoxification in the second trimester may be undertaken in small reductions of, for example, 2–3 mg methadone every 3–5 days but if there is any ongoing illicit use, that there should be a focus on re-stabilization on an opioid substitute. They also caution against detoxification in the third trimester as maternal withdrawal has been associated with fetal distress, preterm delivery and stillbirth.

WHO guidelines recommend that women who are stable on opioid maintenance treatment with methadone or buprenorphine be encouraged to breastfeed, unless the risks outweigh the benefits. Children should be weaned off breast milk gradually to reduce the risk of withdrawal.13 However, a number of challenges to breastfeeding by women on methadone maintenance therapy have been identified, many of them relating to prolonged hospital stays by neonates in the postpartum, sometimes in the intensive care setting.50

Psychosocial interventions

WHO guidelines recommend combining psychosocial and pharmacological interventions in the management of substance misuse in pregnancy, although there is more evidence needed on their effectiveness.13 A systematic review of psychosocial interventions for pregnant women in outpatient drug treatment programs compared to other interventions yielded 14 studies, most of which involved women misusing opioids.51 Studies looked at motivational interviewing and contingency-based management strategies. Motivational interviewing uses the trans-theoretical model of change52 to explore with the patient readiness to change and move them closer to behavior change. Contingency management uses positive reinforcement techniques to support and reward positive behavior. Compared to treatment as usual, which is often specialist substance misuse services, neither was able to demonstrate superiority in terms of significant improvements in maternal outcomes (retention in treatment or abstinence) or neonatal outcomes (prematurity and low birth weight), although contingency management did result in neonates remaining in hospital for fewer days after delivery.51

There is some limited evidence to support the use of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) (Figure 2) in the management of opioid dependence during pregnancy. In a study of pregnant women on methadone treatment, CBT significantly reduced risky injecting behaviors but there was no change in sexual risk behaviors, drug use or injection frequency.53

2

What is cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)? CBT is a form of short-term psychological therapy based around cognitive and behavioral psychological theories that how we think affects how we behave which in turn affects how we feel, which feeds back in to how we think, in a cyclical fashion. The aim of CBT is to identify unhelpful thoughts and behaviors that maintain this cycle.

CANNABIS AND SYNTHETIC CANNABINOID RECEPTOR AGONISTS

Cannabis is one of the most commonly used substances of misuse during pregnancy.54 Synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonists (SCRAs), for example ‘Spice’, are very potent stimulators of the endocannabinoid system and are an increasingly misused and harmful group of psychoactive substances. The legalization of cannabis in some parts of the world has perhaps contributed to a perception that cannabis use during pregnancy is safe. However, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC): the major psychoactive component of cannabis, readily crosses the placental barrier55 and there is some evidence associating cannabis with a range of adverse obstetric and neonatal outcomes. These include low birth weight and preterm birth; while one large retrospective cohort demonstrated an increased risk for such morbidities,56 another retrospective cohort did not.57 Both studies controlled for concurrent use of other substances. Regarding neurobehavioral outcomes in the child, there is some limited evidence for impairments in executive functioning, reduced educational performance and behavioral problems in children exposed to cannabis in utero.58 There is little known about timing of exposures in relation to these longer-term outcomes.58 Thus the data surrounding harm to the developing child from cannabis are inconclusive. There is even less known about the effect of SCRAs but animal and very limited human studies suggest potential adverse effects on both fertility and obstetric outcomes, for example preterm birth.59 British Association of Psychopharmacology (BAP) guidelines recommend that women misusing cannabis in pregnancy should be encouraged to achieve complete abstinence.14,60 Likewise for SCRAs, while there are now UK management guidelines for the non-pregnant population,61 there is little guidance for women during pregnancy. Given the potential for harm to the developing fetus, women should also be made aware of such risks and encouraged to achieve abstinence. As with many other substances misused during pregnancy, the decision as to whether to breastfeed should be on an individual, case by case basis, in discussion with the mother; there is some evidence of transfer of cannabis in to breastmilk62 and guidelines are conflicting as to whether breastfeeding should be undertaken in women who continue to misuse cannabis.55

Pharmacological interventions

There is no evidence to support the use of specific pharmacotherapy for cannabis dependence in non-pregnant individuals or in pregnancy. Guidelines stress that instead there should be a focus on psychosocial interventions.13

Psychosocial interventions

There are a range of psychosocial interventions shown to be efficacious in reducing cannabis use; there have been no specific trials during pregnancy. These include CBT (see Figure 2), motivational interviewing and contingency management (see section on Opioids).63

BENZODIAZEPINES

The prevalence of benzodiazepine misuse during pregnancy is unknown, as epidemiological studies rarely comment on exclusive use of benzodiazepines. However, in a study of pregnant women with opioid dependence, 44% of women screened were positive for benzodiazepine misuse.42 This is important when one considers that co-morbid benzodiazepine misuse may exacerbate the neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) associated with opioid misuse during pregnancy (see section on Opioids and Figure 1 for more information on the clinical features of NAS).

The teratogenicity of benzodiazepines during pregnancy is unclear. However, this must be weighed against the benefits of their short-term use in alcohol detox during pregnancy. There have been concerns regarding associations with congenital anomalies, such as cleft palate. However, many of these studies failed to control for concurrent prescribed medication or illicit drug use. Moreover, a meta-analysis comparing results of cohort versus case–control studies only found a significant association in case–control studies,64 highlighting some possible recall bias inherent to case–control study design. Another meta-analysis found no evidence of an increased risk for congenital anomalies following first trimester exposure.65 There are also some data to suggest an association with low birth weight.66 ‘Floppy baby syndrome’ has been reported in neonates exposed to benzodiazepines in utero. Symptoms include poor muscle tone, hypothermia, lethargy and breathing and feeding difficulties; management is supportive. Data regarding longer-term developmental outcomes are limited, although a large Danish national register study suggests possible delays in psychomotor development.67

There is transfer of benzodiazepines into breast milk; while there is less concern about breastfeeding when benzodiazepines are taken at normal prescribed doses, higher doses may lead to infant sedation, irritability and withdrawal symptoms. Thus WHO caution against breastfeeding when benzodiazepines are being used at high doses.13 Clearly, ‘normal prescribed doses’ may vary internationally and with guidelines not providing an indication of this and the limited evidence, this advice should be applied with caution.

Pharmacological interventions

While there is little evidence on the optimum approach to management of benzodiazepine dependence, WHO guidelines strongly recommend that pregnant women undergo a gradual dose reduction using long-acting benzodiazepines such as diazepam at the lowest effective dose, but only for as long as is required to manage the symptoms of withdrawal. A gradual taper will reduce the symptoms of withdrawal and reduce the risk of exacerbation of symptoms in those being prescribed benzodiazepines as part of the treatment of a mental disorder. Guidelines also suggest that inpatient admission be considered during this time given the serious risks of benzodiazepine withdrawal, which include seizures.13,14

Psychosocial interventions

Both WHO and BAP guidelines recommend that psychosocial interventions be provided during the period of benzodiazepine withdrawal.13,14 As with all substance dependence, referral to a substance misuse service, if available, can help with relapse prevention and recovery, although relapse prevention services can be offered in the absence of specialist services.68

STIMULANTS (INCLUDING COCAINE, AMPHETAMINES AND MEPHEDRONE)

The prevalence of cocaine use in pregnancy (in a US sample) is around 1%. Cocaine and amphetamines are vasoconstrictors so their use during pregnancy can affect the fetus at any stage of gestation.69 Teratogenicity has not been confirmed but a range of congenital anomalies across the skeletal, cardiovascular, central nervous, genitourinary and gastrointestinal systems have been reported with cocaine exposure during pregnancy.69 Its use has also been associated with low birth weight, preterm birth, placental abruption and premature rupture of membranes.63 Mephedrone belongs to the cathinone group of stimulants. While little is known about the effects on the fetus, it too is a vasoconstrictor so may carry similar risks.

When studying longer-term neurobehavioral outcomes in offspring exposed to cocaine, as with most of the substance misuse literature, isolating the effect of exposure to a single drug amidst the confounders of the wider social environment and exposure to other adversities is difficult. While some studies report delays in language and motor development,70,71 a systematic review of the literature found little evidence to support long-term developmental deficits up to the age of 6 years, following cocaine exposure.72 Methamphetamine use is similarly associated with adverse obstetric and neonatal outcomes, including low birth weight and adverse neurobehavioral outcomes.63

Women using stimulants during pregnancy should be encouraged to stop completely and should not breastfeed.13,69 A neonatal withdrawal syndrome has been reported in some infants exposed to stimulants during pregnancy involving withdrawal symptoms such as vomiting and restlessness, although stimulant withdrawal in infants is not as well defined a syndrome as the neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) associated with opioid exposure and withdrawal symptoms are thought to be less severe.73 Given the potential risks outlined above, close monitoring of the pregnancy and infant, particularly fetal growth, is required.

Pharmacological interventions

There are no clinically effective substitute or relapse prevention medications to treat stimulant dependence in non-pregnant individuals or in pregnancy. Guidelines recommend psychosocial interventions instead.13 However, WHO guidelines recommend that, where available, inpatient care be considered in the management of stimulant withdrawal during pregnancy.13

Psychosocial interventions

UK Department of Health guidelines suggest that psychological therapies, including family interventions, should be offered to this group of women.12 A systematic review of psychosocial interventions for pregnant women in outpatient drug treatment programs previously described above also included women with cocaine dependence.51 While neither motivational interviewing nor contingency management demonstrated superiority in terms of significant improvements in maternal or neonatal outcomes, contingency management resulted in neonates remaining in hospital for fewer days after delivery.51 Indeed, in the non-perinatal population, contingency management strategies have shown some benefit in lowering cocaine use.74 An intervention in South Africa involving reinforcement-based therapy (RBT), previously shown to be effective in reducing stimulant use, for pregnant methamphetamine users demonstrated reductions in methamphetamine use, although use was reduced across both the intervention and control (psychoeducation) groups with little difference seen between groups.75 RBT uses behavioral psychology principles such as operant conditioning (that behavior is based on the consequences of previous actions) and social learning theory (behavior is shaped by the wider social context through the process of observing others).

CONCLUSION

Substance misuse is a significant contributor to maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality, with longer-term impacts on the well-being of the mother, child, wider family and society. Therefore the management of the pregnant woman misusing substances must be holistic, utilizing expertise across social, medical and psychological disciplines. A risk-benefit discussion with the woman herself, informed by the latest evidence, ensures a collaborative management plan, which will help to improve outcomes for mother and child.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- There should be routine and sensitive enquiry about substance misuse, including alcohol, tobacco and novel psychoactive substances, in all women who present for antenatal care. Dependence on prescribed medication such as opioids should also be considered.

- Substance misuse in pregnancy may be co-morbid with mental disorder and physical ill health and increase the risk of exposure to violence, abuse and exploitation. It may also result in decline in functioning, loss of employment and family breakdown. Clinicians should be alert to and ready to enquire about these other social, physical and mental co-morbidities, as they can affect engagement with treatment.

- Early brief interventions may be done by non-specialists. However, pregnant women misusing substances and their partners should be fast-tracked into treatment. This may or may not be a specialist addiction service, depending on availability of such services.

- Psychosocial interventions should be considered for women misusing substances in pregnancy.

- Teams working with the woman should aim for early information sharing, within the confines of data protection laws, and integrated care between social work, primary care, maternity, mental health and addiction services, where available.

- Clinicians treating opioid dependence in pregnant women with substitute medication should strike a balance between reducing the amount of prescribed medication in order to reduce fetal withdrawal symptoms and the risk of the patient returning to, or increasing, their misuse of drugs. Opioid maintenance therapy is generally recommended.

- Any neonate exposed to substances in utero which could cause withdrawal symptoms or other complications should be monitored and appropriately treated in the neonatal period. Non-pharmacological approaches such as low lighting, skin-to-skin contact and quiet environments should be employed for all neonates exposed to substances in utero.

- Not all substance misuse is an absolute contraindication to breastfeeding. Breastfeeding should always be an individual discussion with the mother about relative risks and benefits in light of the latest evidence.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Professor Anne Lingford-Hughes has received Honoraria paid into her institutional funds for speaking and chairing engagements from Lundbeck, Lundbeck Institute UK, Janssen-Cilag, Pfizer, Servier; received research grants or support from Lundbeck, GSK; unrestricted funds support from Alcarelle for a PhD; consulted by Silence, NET Device Corps, Sanofi-Aventis and also consulted by but received no monies from Britannia Pharmaceuticals, GLG, Opiant, Lightlake and Dobrin.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

RELEVANT GUIDELINES AND POLICIES

- UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Clinical guideline (CG192)- Antenatal and postnatal mental health: clinical management and service guidance (2018). Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG192

- US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Clinical guidance for treating pregnant and parenting women with opioid use disorder and their infants (2018). Available from: https://store.samhsa.gov/product/Clinical-Guidance-for-Treating-Pregnant-and-Parenting-Women-With-Opioid-Use-Disorder-and-Their-Infants/SMA18-5054

- UK Department of Health. Drug misuse and dependence: UK guidelines on clinical management (2017). Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/drug-misuse-and-dependence-uk-guidelines-on-clinical-management

- British Association for Psychopharmacology (BAP). Consensus guidance on the use of psychotropic medication preconception, in pregnancy and postpartum (2017). Available from: https://www.bap.org.uk/pdfs/BAP_Guidelines-Perinatal.pdf

- World Health Organisation (WHO). Guidelines for the identification and management of substance use and substance use disorders in pregnancy (2014). Available from: http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/publications/pregnancy_guidelines/en/

- British Association for Psychopharmacology (BAP). Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological management of substance abuse, harmful use, addiction and comorbidity (2012). Available from: https://www.bap.org.uk/pdfs/BAP_Guidelines-Addiction.pdf

- UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Clinical guideline (CG110)- Pregnancy and complex social factors: a model for service provision for pregnant women with complex social factors (2010). Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/CG110

REFERENCES

WHO. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines Geneva: World Health Organisation. | |

WHO. Management of substance abuse: Facts and figures [Available from: http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/facts/en/]. | |

Klee H. Drug-using parents: analysing the stereotypes. International Journal of Drug Policy 1998;9(6):437–48. | |

Mayet S, Mayet S, Groshkova T, Mayet S, Groshkova T, Morgan L, et al. Drugs and pregnancy—outcomes of women engaged with a specialist perinatal outreach addictions service. Drug and Alcohol Review 2008;27(5):497–503. | |

Kaltenbach K, Finnegan L. Children of maternal substance misusers. Current Opinion in Psychiatry 1997;10(3):220–4. | |

Nair M, Knight M, Kurinczuk JJ. Risk factors and newborn outcomes associated with maternal deaths in the UK from 2009 to 2013: a national case–control study. BJOG 2016;123(10):1654–62. | |

Ross LE, Dennis CL. The prevalence of postpartum depression among women with substance use, an abuse history, or chronic illness: a systematic review. Journal of Women's Health 2009;18(4):475–86. | |

Gilchrist G, Hegarty K. Tailored integrated interventions for intimate partner violence and substance use are urgently needed. Drug and Alcohol Review 2017;36(1):3–6. | |

Essau CA, Sasagawa S, Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P. The impact of pre- and perinatal factors on psychopathology in adulthood. Journal of Affective Disorders 2018;236:52–9. | |

Kendler K, Ohlsson H, Svikis D, Sundquist K, Sundquist J. The Protective Effect of Pregnancy on Risk for Drug Abuse: A Population, Co-Relative, Co-Spouse, and Within-Individual Analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry 2017;174(10):954–62. | |

Bhuvaneswar CG, Chang G, Epstein LA, Stern TA. Cocaine and Opioid Use During Pregnancy: Prevalence and Management. Primary Care Companion to The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 2008;10(1):59–65. | |

Clinical Guidelines on Drug Misuse and Dependence Update 2017 Independent Expert Working Group. Drug misuse and dependence: UK guidelines on clinical management. London: Department of Health, 2017; https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/drug-misuse-and-dependence-uk-guidelines-on-clinical-management. | |

WHO. Guidelines for the identification and management of substance use and substance use disorders in pregnancy. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2014; http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/publications/pregnancy_guidelines/en/. | |

McAllister-Williams RH, Baldwin DS, Cantwell R, Easter A, Gilvarry E, Glover V, et al. British Association for Psychopharmacology consensus guidance on the use of psychotropic medication preconception, in pregnancy and postpartum. Journal of Psychopharmacology 2017;31(5):519–52. | |

NICE. Pregnancy and complex social factors: A model for service provision for pregnant women with complex social factors. NICE Guidelines CG110. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2010; https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg110. | |

Popova S, Lange S, Probst C, Gmel G, Rehm J. Estimation of national, regional, and global prevalence of alcohol use during pregnancy and fetal alcohol syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Global Health 2017;5(3):e290-e9. | |

Flak AL, Su S, Bertrand J, Denny CH, Kesmodel US, Cogswell ME. The Association of Mild, Moderate, and Binge Prenatal Alcohol Exposure and Child Neuropsychological Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 2014;38(1):214–26. | |

O’Leary C, Nassar N, Kurinczuk J, Bower C. The effect of maternal alcohol consumption on fetal growth and preterm birth. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 2009;116(3):390–400. | |

Patra J, Bakker R, Irving H, Jaddoe VWV, Malini S, Rehm J. Dose-response relationship between alcohol consumption before and during pregnancy and the risks of low birth weight, preterm birth and small-size-for-gestational age (SGA) – A systematic review and meta-analyses. BJOG 2011;118(12):1411–21. | |

Mamluk L, Edwards HB, Savović J, Leach V, Jones T, Moore THM, et al. Low alcohol consumption and pregnancy and childhood outcomes: time to change guidelines indicating apparently ‘safe’ levels of alcohol during pregnancy? A systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ Open 2017;7(7). | |

Australian Government Department of Health. National Health and Medical Research Council's Australian Guidelines to Reduce Health Risks from Drinking Alcohol, 2009; https://wwwnhmrcgovau/health-topics/alcohol-guidelines. | |

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Alcohol and pregnancy, 2016; https://wwwcdcgov/vitalsigns/fasd/index.html. | |

Department of Health. UK Chief Medical Officers’ Alcohol Guidelines Review: Summary of the proposed new guidelines. London: Department of Health, 2016; https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/489795/summary.pdf. | |

NICE. Antenatal and postnatal mental health: clinical management and service guidance- CG192. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2014; https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG192. | |

O’Connor MJ, Whaley SE. Brief Intervention for Alcohol Use by Pregnant Women. American Journal of Public Health 2007;97(2):252–8. | |

Stade BC, Bailey C, Dzendoletas D, Sgro M, Dowswell T, Bennett D. Psychological and/or educational interventions for reducing alcohol consumption in pregnant women and women planning pregnancy. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009(2):CD004228-CD. | |

Lange S, Probst C, Rehm J, Popova S. National, regional, and global prevalence of smoking during pregnancy in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Global Health 2018;6(7):e769-e76. | |

Cohen A, Osorio R, Page LM. Substance misuse in pregnancy. Obstetrics, Gynaecology & Reproductive Medicine 2017. | |

Chamberlain C, O'Mara-Eves A, Porter J, Coleman T, Perlen SM, Thomas J, et al. Psychosocial interventions for supporting women to stop smoking in pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2017(2). | |

Howard LM, Bekele D, Rowe M, Demilew J, Bewley S, Marteau TM. Smoking cessation in pregnant women with mental disorders: a cohort and nested qualitative study. Bjog. 2013;120(3):362–70. | |

WHO. Electronic nicotine delivery systems and electronic non-nicotine delivery systems. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2016; www.who.int/fctc/cop/cop7/FCTC_COP_7_11_EN.pdf?ua=1. | |

Coleman T, Chamberlain C, Davey MA, Cooper SE, Leonardi-Bee J. Pharmacological interventions for promoting smoking cessation during pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015(12). | |

Schiff DM, Nielsen T, Terplan M, Hood M, Bernson D, Diop H, et al. Fatal and Nonfatal Overdose Among Pregnant and Postpartum Women in Massachusetts. Obstetrics & Gynecology 9000;Publish Ahead of Print. | |

Winklbaur B, Kopf N, Ebner N, Jung E, Thau K, Fischer G. Treating pregnant women dependent on opioids is not the same as treating pregnancy and opioid dependence: a knowledge synthesis for better treatment for women and neonates. Addiction 2008;103(9):1429–40. | |

Jansson LM, Velez M. Neonatal abstinence syndrome. Current Opinion in Pediatrics 2012;24(2):252–8. | |

Siu A, Robinson CA. Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome: Essentials for the Practitioner. The Journal of Pediatric Pharmacology and Therapeutics: JPPT 2014;19(3):147–55. | |

Kraft WK, Adeniyi-Jones SC, Chervoneva I, Greenspan JS, Abatemarco D, Kaltenbach K, et al. Buprenorphine for the Treatment of the Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome. New England Journal of Medicine 2017;376(24):2341–8. | |

NICE. Methadone and buprenorphine for the management of opioid dependence. NICE Technology Appraisal Guidance TA114, 2007 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/TA114. | |

Burns L, Mattick RP, Lim K, Wallace C. Methadone in pregnancy: treatment retention and neonatal outcomes. Addiction 2007;102(2):264–70. | |

Hulse GK, Milne E, English DR, Holman CDJ. The relationship between maternal use of heroin and methadone and infant birth weight. Addiction 1997;92(11):1571–9. | |

Wittmann BK, Segal S. A Comparison of the Effects of Single- and Split-Dose Methadone Administration on the Fetus: Ultrasound Evaluation. International Journal of the Addictions 1991;26(2):213–8. | |

Jones HE, Kaltenbach K, Heil SH, Stine SM, Coyle MG, Arria AM, et al. Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome after Methadone or Buprenorphine Exposure. The New England Journal of Medicine 2010;363(24):2320–31. | |

Minozzi S, Amato L, Bellisario C, Ferri M, Davoli M. Maintenance agonist treatments for opiate-dependent pregnant women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013(12). | |

Zedler BK, Mann AL, Kim MM, Amick HR, Joyce AR, Murrelle EL, et al. Buprenorphine compared with methadone to treat pregnant women with opioid use disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of safety in the mother, fetus and child. Addiction (Abingdon, England) 2016;111(12):2115–28. | |

Nechanská B, Mravčík V, Skurtveit S, Lund IO, Gabrhelík R, Engeland A, et al. Neonatal outcomes after fetal exposure to methadone and buprenorphine: national registry studies from the Czech Republic and Norway. Addiction 2018;113(7):1286–94. | |

Cleary BJ, Donnelly J, Strawbridge J, Gallagher PJ, Fahey T, Clarke M, et al. Methadone dose and neonatal abstinence syndrome – systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction 2010;105(12):2071–84. | |

Kuschel CA, Austerberry L, Cornwell M, Couch R, Rowley RSH. Can methadone concentrations predict the severity of withdrawal in infants at risk of neonatal abstinence syndrome? Archives of Disease in Childhood – Fetal and Neonatal Edition 2004;89(5):F390-F3. | |

Dryden C, Young D, Hepburn M, Mactier H. Maternal methadone use in pregnancy: factors associated with the development of neonatal abstinence syndrome and implications for healthcare resources. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 2009;116(5):665–71. | |

Terplan M, Laird HJ, Hand DJ, Wright TE, Premkumar A, Martin CE, et al. Opioid Detoxification During Pregnancy: A Systematic Review. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2018;131(5):803–14. | |

Hicks J, Morse E, Wyant DK. Barriers and Facilitators of Breastfeeding Reported by Postpartum Women in Methadone Maintenance Therapy. Breastfeeding Medicine 2018;13(4):259–65. | |

Terplan M, Ramanadhan S, Locke A, Longinaker N, Lui S. Psychosocial interventions for pregnant women in outpatient illicit drug treatment programs compared to other interventions. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015(4). | |

Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The Transtheoretical Model of Health Behavior Change. American Journal of Health Promotion 1997;12(1):38–48. | |

O'Neill K, Baker A, Cooke M. Evaluation of a cognitive-behavioural intervention for pregnant injecting drug users at risk of HIV infection. Addiction 1996;91(8):1115–25. | |

Metz TD, Stickrath EH. Marijuana use in pregnancy and lactation: a review of the evidence. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2015;213(6):761–78. | |

Jansson LM, Jordan CJ, Velez ML. Perinatal marijuana use and the developing child. JAMA 2018;320(6):545–6. | |

Hayatbakhsh MR, Flenady VJ, Gibbons KS, Kingsbury AM, Hurrion E, Mamun AA, et al. Birth outcomes associated with cannabis use before and during pregnancy. Pediatric Research 2011;71:215. | |

Conner SN, Carter EB, Tuuli MG, Macones GA, Cahill AG. Maternal marijuana use and neonatal morbidity. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2015;213(3):422.e1-.e4. | |

Warner TD, Roussos-Ross D, Behnke M. It's not your mother's marijuana: effects on maternal-fetal health and the developing child. Clinics in perinatology 2014;41(4):877–94. | |

Sun X, Dey SK. Synthetic cannabinoids and potential reproductive consequences. Life sciences 2014;97(1):72–7. | |

Lingford-Hughes AR, Welch S, Peters L, Nutt D. BAP updated guidelines: evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological management of substance abuse, harmful use, addiction and comorbidity: recommendations from BAP. Journal of Psychopharmacology 2012;26(7):899–952. | |

Abdulrahim DB-J, O; on behalf of NEPTUNE group. Harms of Synthetic Cannabinoid Receptor Agonists (SCRAs) and Their Management. London: Novel Psychoactive Treatment UK Network (NEPTUNE), 2016. | |

Baker T, Datta P, Rewers-Felkins K, Thompson H, Kallem RR, Hale TW. Transfer of Inhaled Cannabis Into Human Breast Milk. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2018;131(5):783–8. | |

Forray A, Foster D. Substance use in the perinatal period. Current Psychiatry Reports 2015;17(11):91. | |

Dolovich LR, Addis A, Vaillancourt JMR, Power JDB, Koren G, Einarson TR. Benzodiazepine use in pregnancy and major malformations or oral cleft: meta-analysis of cohort and case-control studies. BMJ 1998;317(7162):839–43. | |

Ban L, West J, Gibson JE, Fiaschi L, Sokal R, Doyle P, et al. First trimester exposure to anxiolytic and hypnotic drugs and the risks of major congenital anomalies: a United Kingdom population-based cohort study. PLoS One 2014;9(6):e100996. | |

Mohammad Masud Iqbal, Tanveer Sobhan, Thad Ryals. Effects of Commonly Used Benzodiazepines on the Fetus, the Neonate, and the Nursing Infant. Psychiatric Services 2002;53(1):39–49. | |

Mortensen JT, Olsen J, Larsen H, Bendsen J, Obel C, Sørensen HT. Psychomotor development in children exposed in utero to benzodiazepines, antidepressants, neuroleptics, and anti-epileptics. European Journal of Epidemiology 2003;18(8):769–71. | |

Gopalan P, Glance JB, Azzam PN. Managing benzodiazepine withdrawal during pregnancy: case-based guidelines. Archives of Women's Mental Health 2014;17(2):167–70. | |

McLafferty LP, Becker M, Dresner N, Meltzer-Brody S, Gopalan P, Glance J, et al. Guidelines for the Management of Pregnant Women With Substance Use Disorders. Psychosomatics 2016;57(2):115–30. | |

Bandstra ES, Vogel AL, Morrow CE, Xue L, Anthony JC. Severity of Prenatal Cocaine Exposure and Child Language Functioning Through Age Seven Years: A Longitudinal Latent Growth Curve Analysis. Substance Use & Misuse 2004;39(1):25–59. | |

Fallone MD, LaGasse LL, Lester BM, Shankaran S, Bada HS, Bauer CR. Reactivity and regulation of motor responses in cocaine-exposed infants. Neurotoxicology and Teratology 2014;43:25–32. | |

Frank DA, Augustyn M, Knight WG, Pell T, Zuckerman B. Growth, Development, and Behavior in Early Childhood Following Prenatal Cocaine Exposure: A Systematic Review. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 2001;285(12):1613–25. | |

Neonatal Drug Withdrawal. Pediatrics 1998;101(6):1079–88. | |

Knapp WP, Soares B, Farrell M, Silva de Lima M. Psychosocial interventions for cocaine and psychostimulant amphetamines related disorders. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2007(3). | |

Jones HE, Myers B, O'Grady KE, Gebhardt S, Theron GB, Wechsberg WM. Initial Feasibility and Acceptability of a Comprehensive Intervention for Methamphetamine-Using Pregnant Women in South Africa. Psychiatry Journal 2014;2014:8. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards programme CLICK HERE)