This chapter should be cited as follows:

McKenna M, Miller C, Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.420653

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Gynecology Module

Volume 8

Gynecological endoscopy

Volume Editors:

Professor Alberto Mattei, Director Maternal and Child Department, USL Toscana Centro, Italy

Dr Federica Perelli, Obstetrics and Gynecology Unit, Ospedale Santa Maria Annunziata, USL Toscana Centro, Florence, Italy

Chapter

The New Endoscopic Era: Peculiarities and Controversies

First published: March 2024

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

INTRODUCTION

The road to the modern laparoscopy was paved with many controversies, failures, and trials and errors. The history of the modern laparoscopy starts over 200 years ago and is intimately intertwined with gynecology. In 1805, Phillip Bozzini invented the Lichtleiter – a lighting apparatus supporting visualization of the bladder and rectum through mirror-reflected candlelight.1 In 1865, Antoine Jean Desormeaux, a French physician, built on this light source to effectively create and present the first functional cystoscopy.1 From here, Pantaleoni adapted the device, and in 1869, performed the first hysteroscopy where he was able to identify an intrauterine polyp in a 60 year old with postmenopausal bleeding and cauterize it with silver nitrate.2 Over the next 50 years, these endoscopic tools were further honed until laparoscopy was eventually created in 1910 by Hans Jacobaeus, a Swedish internist, who used a proctoscope to perform the first laparoscopy.3

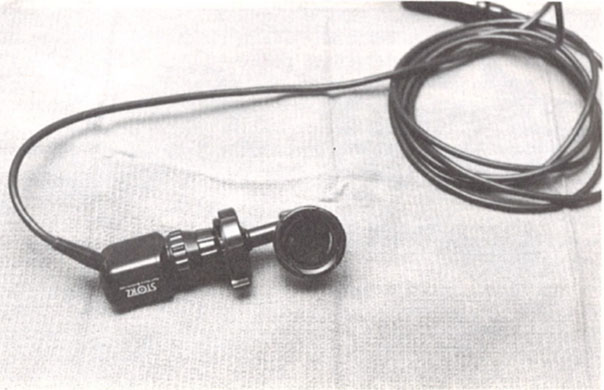

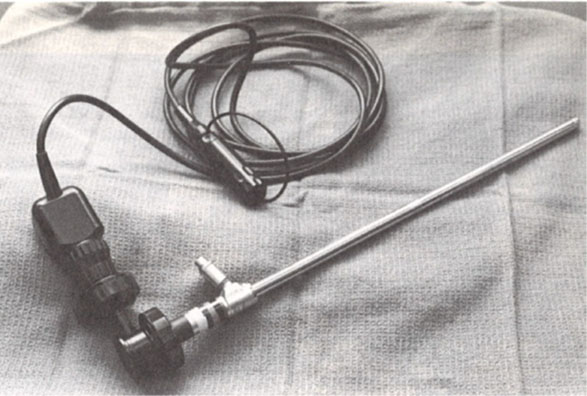

In 1950, Fervers performed laparoscopic adhesiolysis with biopsy instruments and used oxygen as a distension medium. The procedure caused great concern when the oxygen caused an audible explosion, leading to the use of CO2 as the modern-day distension medium. It was gynecologists in the 1980s who truly saw the utility of laparoscopy and started using it to treat pelvic adhesions and endometriosis.4,5,6 In the 1980s, Professor Kurt Semm introduced endoloops and mechanical morcellation by hand that allowed more procedures to be done laparoscopically instead of the traditional open route (Figure 1). It was also during this time that Dr Camran Nezhat combined the laparoscope and a television monitor, allowing surgeons to stand erect and operate with two hands, as opposed to bending over to look through a scope (Figure 2).7 It has only been through these innovations, controversies, trials, and errors that laparoscopy has evolved to become the gold standard of most gynecologic surgeries today. However, controversies in gynecologic laparoscopy remain, including morcellation of hysterectomy specimens and fibroids at the time of myomectomy, management of bowel endometriosis and whether nerve sparing in endometriosis surgery is of utility.

1

Endoloops.

|

Beam splitter attached to a laparoscope |

Camera attached to a beam splitter |

Beam splitter with a camera attached to a laparoscope |

| |

2

Beam splitter.

MORCELLATION: CONTAINED VERSUS UNCONTAINED

One of the most controversial topics today is morcellation of tissue that is to be removed from the abdomen. Specifically, is there a place for the power morcellator and should morcellation be performed in a containment system? Morcellation of tissue refers to dividing a larger tissue specimen into smaller pieces that are then removed through small incisions in the abdomen. While laparoscopy allows for very small incisions to treat large pathology, it brings with it the additional challenge of removing that pathology through much smaller incisions. The very first documented uterine morcellation procedure was performed in 1840 by Ammasut of France to deliver a fibroid uterus through the vagina. In 1899, William Pryor described the technique of transvaginal wedge morcellation of a large uterus.8 Historically physicians relied on manual morcellation of the uncontained specimen through larger abdominal incisions or through the vagina.9 However, as this can often take copious amounts of time, as well as surgeon energy to perform by hand, innovation started to take place. Starting in 1988, Kurt Semm developed a manually operated morcellation device that could sequentially remove small pieces of tissue. However, it required repeated squeezing of a handle, which led to surgeon fatigue, causing it to fall from favor given the exertion required for its function.9,10

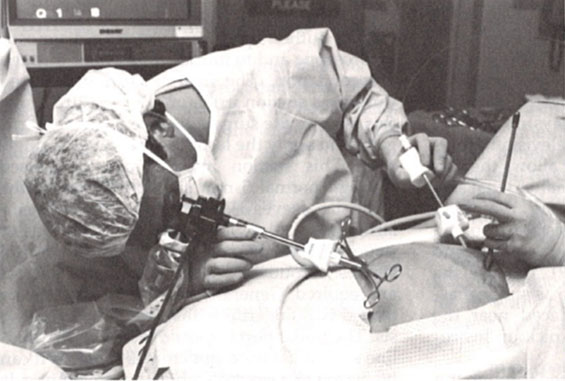

In 1992, Steiner et al.11 introduced the very first electric morcellation device (Figure 3). The system consisted of two elements: a cutting device and electric engine. The author reviewed 11 cases in which the device was used to remove fibroids or ovaries in which there were no reported surgical complications and pathologists obtained accurate histologic analysis.11 Since 1992 there have been many different types of electronic morcellation machines developed, all with the basic principle of a sheath, grasper and cutting blade that produces tissue that can be removed through smaller incisions. Overall, the electric morcellator is advantageous in preserving surgeon energy as well as decreasing operative time. However, as morcellation was used in an uncontained system, there were reports of various injuries from the device and the development of subsequent parasitic fibroids in the abdomen. A review by Milad and Milad12 looked at morcellator related injuries from 1993 to 2014 and found a total of 55 morcellator-related injuries. The injuries involved the small bowel, vascular system, kidney, ureter, bladder, and diaphragm, and of these injuries, 11 involved more than one organ. Six deaths were attributed to morcellator-related complications. There were also concerns of potential spread of malignant tissue fragments in the abdomen, potentially upstaging any cancer diagnosis and ultimately adversely impacting morbidity and mortality.12

3

Steiner morcellator.

In April 2014, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) published a warning that electronic power morcellation could increase the risk of tumor spread if specimens were inadvertently sarcomas.13 As a result of this communication, hospitals and hospital systems banned the use of power morcellators. The FDA quoted the risk of sarcoma as 1 in 458 when making this statement, which was a much higher percentage than had been seen or quoted in the literature.14 Rigorous retrospective studies done by Pritts et al. and Bojahr subsequently demonstrated the risk of sarcoma was far lower than cited by the FDA (1/1960 and 2/8720).15 In 2014, Jubilee Brown published an article describing the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists stance on power morcellation emphasizing the importance of power morcellation and that with appropriate informed consent it should remain available to appropriately screened women at low risk, given the overall low risk of sarcoma.16 In 2019 ACOG published a committee opinion on morcellation stating similar sentiments, morcellation is appropriate in low-risk, appropriately screened patients after shared decision making between patient and provider given the extremely low risk of unknown leiomyosarcoma ranging from 1 in 770 surgeries to 1 in 10,000.17 Given these lower numbers, the FDA amended their initial warning to recommend the performance of power morcellation in a containment system.18 However, the damage had been done and two major medical companies stopped production of their morcellators and many hospitals continued to ban electronic-power morcellators given the tumultuous business landscape. As a result, most surgeons abandoned power morcellation and returned to hand morcellation at the umbilicus or via mini-laparotomy.

While most surgeons now make it their routine practice to morcellate, whether by hand or electronic power in a contained system, there is a group that does not think a contained system is beneficial. Although risk is low, it is well known that uncontained morcellation can lead to parasitic myomas, spreading of occult malignancy and inherent surgical complications, including potential damage to organs.9 One certainly must acknowledge malignancy risk when a fibroid is dissected from its myometrial capsule, as fragments are dispersed throughout the abdomen from the procedure itself. Ultimately, this makes total containment impossible and the containment bag almost inconsequential in the face of malignancy.10,14 However, in-bag morcellation does appear to lower risk of parasitic myomas and is safe. Studies looking at perioperative outcomes of patients undergoing contained morcellation versus uncontained morcellation found no difference in blood loss, length of stay, pathology, complication, and uterine weight.19,20 There was operative time difference with contained morcellation taking 20 to 26 minutes longer than uncontained morcellation procedures.19,20

Ultimately, the practice of morcellation in a contained versus uncontained system is still debated by some physicians, and until more data are presented physicians will continue to practice as they always have.

HOW RADICAL SHOULD WE BE WITH DEEP INFILTRATING ENDOMETRIOSIS?

Another hotly debated concept in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery is the optimal treatment of deeply infiltrative endometriosis, specifically deeply infiltrative bowel endometriosis, as there is no consensus in the literature as to how to treat these patients. This lack of consensus is due to a significant paucity in the literature in regards to management of deep infiltrating endometriosis in terms of improvement in both pain and fertility. There are only single institution case studies or meta-analysis studies looking at the management of deep infiltrating endometriosis, with very few looking at fertility. Of those looking at fertility it is not clear in most of the studies which patients were actively attempting pregnancy versus not attempting or not desiring fertility and whether they were using ART to achieve pregnancy.21 Additionally, the mean period for conception following surgery is also not generally noted in these studies.21

There are three types of endometrioses that exist in the pelvis: peritoneal endometriosis, ovarian endometriosis, and deep infiltrating endometriosis. Deep infiltrating endometriosis is defined as extending more than 5 mm beneath the peritoneum and can be detected on the following pelvic structures or organs: uterosacral ligaments, vagina, bowel, bladder, and ureters. Deep bowel endometriosis is defined as the infiltration of the muscular layer of the bowel. It can affect any area of the bowel. However, the most commonly affected are the rectum, rectosigmoid junction, or the sigmoid.22 Other less commonly affected areas are the appendix, small bowel, or cecum.22 The prevalence of colorectal endometriosis is reported to be 8–12% of patients with endometriosis, with 90% of the lesions seen in the rectosigmoid region.23,24,25 Patients often complain of diarrhea, dyschezia and bowel cramping along with dyspareunia and significant dysmenorrhea.21,22 Endometriosis affects 6–10% of reproductive aged women and can be found in premenarchal and postmenopausal women.26 There are debates regarding direct causality of endometriosis and infertility, but it has been found in some studies that endometriosis, particularly deep infiltrating endometriosis, is present in 21–47% of women presenting with infertility.27,28 Despite the dearth of literature, it is more accepted that the more advanced and deeply infiltrating endometriosis should be removed for improved fertility outcomes. The literature does not necessarily show a distinct advantage. A meta-analysis by Adamson et al. demonstrated that patients with ASRM stage three and four endometriosis had improved pregnancy outcomes after excision, going from 4% preoperatively to 43% postoperatively.23,24,25 A recent 2022 meta-analysis by Daniilidis et al. looked at the impact of deep endometriosis surgery on reproductive outcomes and pregnancy rates in women with and without prior infertility.29 In this meta analysis the authors found 23 studies which included 1548 patients from 2010 to 2022 who underwent excision of deep infiltrating endometriosis and found pregnancy rates ranging from18.7% to 83.8% with a mean of 52.6%.29 The variability among the studies included the type of study, whether infertility was noted prior to surgery, extent of excision, and location of each lesion was immense, and often certain variables were not included. Often the fertility component was a secondary objective of the study, with primary objectives typically consisting of change in quality of life and symptom management. This study is further evidence that while surgery has been shown to improve pregnancy outcomes, randomized controlled studies and prospective cohort studies are necessary to specifically look at fertility outcomes after surgery to definitively determine the best management for these patients. Given this evidence, the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology published guidelines on how to treat endometriosis and state that “operative laparoscopy could be offered as a treatment option for endometriosis associated infertility as it improves the rate of ongoing pregnancy,” as well as “although no compelling evidence exists that operative laparoscopy for deep endometriosis improves fertility, operative laparoscopy may represent a treatment option in symptomatic patients wishing to conceive”.30

It is widely accepted among gynecologists that there is a strong correlation between chronic pelvic pain and endometriosis.31 However, there is significant variation in the literature regarding the number of lesions and whether location of endometriotic lesions correlates with location of pelvic pain in the patient.31,32,33 While it is still debated within the community whether superficial endometriosis is the primary cause of significant pelvic pain, it is widely accepted that deep infiltrating endometriosis is often responsible for significant pelvic pain.32,34,35 Medical management of deep infiltrative endometriosis is ineffective, as fibrosis comprises most of the disease, which does not respond to hormonal management.36,37 Given this, surgical management is the gold standard as it has been proven to improve overall quality of life in these symptomatic patients; despite the risk of significant complications, including pelvic abscess, rectovaginal fistula, ureteral fistula, anastomotic leakage, and even death.37

There have been several studies evaluating treatment of deep infiltrating bowel endometriosis that have found surgical management to improve pain, bowel symptoms, and overall quality of life.28,36,38 However, there is no consensus in the literature regarding the superior method of surgical management, whether it be rectal shaving, segmental disc excision, or segmental colorectal resection.22 A survey in 2015 that looked at 1135 French patients who were managed for colorectal endometriosis found that 48% of the patients were treated with rectal shaving, 40.4% were treated with colorectal segmental resection, and 7.3% underwent disc excision, all according to surgeon and center preference.39

While there are complications associated with all these procedures, the study generally found that surgical management was beneficial for patients suffering symptoms from deep infiltrating endometriosis of the bowel. However, the study did not identify a superior method of surgical management. Rectal recurrence occurred in 8.7% of patients treated with shaving and 4.3% required secondary colorectal resection. 4.3% were treated secondarily by rectal shaving. The authors gleaned from this study that postoperative functional outcomes from colorectal resection and shaving were similar. However, they found the recurrence rate may be increased in those that underwent rectal shaving.40 In general, the thought process is if the deep infiltrating endometriotic lesion extends 50% or more in circumference in relation to the bowel, a colorectal resection is in the best interest of the patient, because a disc resection or shaving would necessitate in suturing a large defect, which could lead to bowel stricture and worsening bowel symptoms.41

Additionally, it has been found that deep infiltrating endometriosis is often multifocal, which sometimes requires multiple shaving or discoid resections that would be better served as a larger segmental colorectal resection.41 Conversely, a review of publications has shown that colorectal bowel resection can result in a higher complication rate compared to shaving and disc excision, particularly for occurrence of rectovaginal fistulas, anastomotic leakage, delayed hemorrhage and long-term bladder catheterization.22 A recent meta-analysis by Quintairos et al. looked at bowel function in women with deep infiltrating endometriosis according to surgical approach (colorectal resection vs. shaving or discoid resection) and could only draw the conclusion based on the paucity of studies and data that conservative surgery (shaving or discoid resection) presented fewer events of constipation and frequent bowel movements than colorectal segmental resection.42

Ultimately, there have been no randomized control trials comparing these three methods to one another, so it remains widely unknown which method results in the least complications with the most symptom benefit regarding bowel function, pelvic pain, and infertility.

IS THERE A PLACE FOR NERVE SPARING IN ENDOMETRIOSIS SURGERY?

The concept of nerve damage in radical surgery has been a topic of interest across many surgical specialties, among which gynecology ranks at the top given the close proximity of pelvic organs to the surrounding autonomic nerves. It is well known that treatment for early cervical cancer is a radical hysterectomy, which along with removal of the cervix and uterus entails the removal of the bilateral parametrium. The bilateral parametrium houses, among other things, autonomic nerves that innervate organs in the pelvis. A common side effect after radical hysterectomy is bladder dysfunction that necessitates prolonged bladder rest due to the disruption of the autonomic nerve innervation to the bladder during parametrial resection. Given the morbidity that comes with this bladder dysfunction, there have been several studies in the gynecologic oncology community looking at sparing these autonomic nerves during the surgery, that ultimately resulted in increased spontaneous voiding postoperatively subsequently decreasing this morbid aspect of the procedure.43

Similarly, it is well known that in extensive resection of deep infiltrating endometriosis the pelvic autonomic nerves can be disrupted if care is not taken to preserve them.44 In a study by Possover et al., 47 patients were investigated who presented to the center with complaints of bladder retention after laparoscopic resection of rectovaginal or parametric deep infiltrating endometriosis.45 They concluded that segmental rectum resection with parametric resection exposed the most patients to the risk of bladder motor paralytic retention. However, they also found a component of chronic myogenic destruction secondary to chronic bladder overdistention likely due to disruption of the pelvic splanchnic nerves.45 Additionally, bowel symptoms such as constipation are also a known complication resulting from excision of deep infiltrating endometriosis and, in particular, colorectal resection likely resulting from transection of the autonomic pelvic nerves innervating the colon and rectum.46 Given all of these known complications, it is argued that careful attention should be paid in preserving these nerves during extensive dissection, especially of the parametrium and uterosacral ligaments.

CONCLUSION

There are many more controversies that are abound in gynecology, and laparoscopy in particular, however, the topics presented here reign as some of the most hotly contested. The common thread amongst all of these topics is a dearth in the literature regarding best practice management. Most of the surgical gynecologic literature available are single institution case studies or meta-analyses which carries bias and makes it difficult to make definitive conclusions from the results. It is imperative that randomized controlled trials focusing on these topics are executed so a consensus can be obtained.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- Contained electronic morcellation should be considered a reasonable and safe alternative to hand morcellation.

- Excision of deep infiltrative endometriosis could greatly benefit patients with infertility as well as pelvic pain and should be considered as the primary treatment for patients with this pathology.

- Nerve sparing in pelvic surgery should be considered in radical surgery to improve bowel and bladder dysfunction postoperatively.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Author(s) statement awaited.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

REFERENCES

Valle RF. Development of hysteroscopy: From a dream to a reality, and its linkage to the present and future. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2007;14(4):407–18. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2007.03.002. | |

Tarneja P, Duggal B. Hysteroscopy: Past, Present and Future. Med J Armed Forces India 2002;58(4):293–4. doi:10.1016/S0377-1237(02)80079-X. | |

Hatzinger M, Kwon S t, Langbein S, et al. Hans Christian Jacobaeus: Inventor of Human Laparoscopy and Thoracoscopy. J Endourol 2006;20(11):848–50. doi:10.1089/end.2006.20.848. | |

Nezhat C, Crowgey SR, Garrison CP. Surgical treatment of endometriosis via laser laparoscopy*. Fertil Steril 1986;45(6):778–83. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(16)49392-1. | |

Daniell J. Laser Laparoscopy for Endometriosis. https://home.liebertpub.com/gyn. doi:10.1089/gyn.1984.1.185. | |

Wallwiener D, Pollmann D, Stolz W, et al. Laser in Gynecology: An Overview. In: Bastert G, Wallwiener D. (eds.) Lasers in Gynecology: Possibilities and Limitations. Springer, 1992:3–16. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-45683-1_1. | |

Spaner SJ, Warnock GL. A Brief History of Endoscopy, Laparoscopy, and Laparoscopic Surgery. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech 1997;7(6):369–73. doi:10.1089/lap.1997.7.369. | |

Electric Morcellation-related Reoperations After Laparoscopic Myomectomy and Nonmyomectomy Procedures – ClinicalKey. Accessed August 22, 2022. https://www.clinicalkey.com/#!/content/playContent/1-s2.0-S1553465014012928?returnurl=https:%2F%2Flinkinghub.elsevier.com%2Fretrieve%2Fpii%2FS1553465014012928%3Fshowall%3Dtrue&referrer=https:%2F%2Fpubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov%2F. | |

Miller CE. Morcellation equipment: past, present, and future. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2018;30(1):69–74. doi:10.1097/GCO.0000000000000435. | |

Parker WH. Indications for morcellation in gynecologic surgery. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2018;30(1):75–80. doi:10.1097/GCO.0000000000000427. | |

Steiner RA, Wight E, Tadir Y, et al. Electrical cutting device for laparoscopic removal of tissue from the abdominal cavity. Obstet Gynecol 1993;81(3):471–4. | |

Milad MP, Milad EA. Laparoscopic morcellator-related complications. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2014;21(3):486–91. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2013.12.003. | |

Health C for D and R. Safety Communications – Laparoscopic Uterine Power Morcellation in Hysterectomy and Myomectomy: FDA Safety Communication. Accessed August 22, 2022. https://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/20170406071822/https://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/ucm393576.htm. | |

Parker W, Pritts E, Olive D. Morcellation for Gynecologic Surgery. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2019;62(4):727–32. doi:10.1097/GRF.0000000000000485. | |

Pritts EA, Vanness DJ, Berek JS, et al. The prevalence of occult leiomyosarcoma at surgery for presumed uterine fibroids: a meta-analysis. Gynecol Surg 2015;12(3):165–77. doi:10.1007/s10397-015-0894-4. | |

Brown J. AAGl Advancing Minimally Invasive Gynecology Worldwide: Statement to the FDA on Power Morcellation. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 1024;21:970-1 | |

Uterine Morcellation for Presumed Leiomyomas, Accessed November 18, 2023. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2021/03/uterine-morcellation-for-presumed-leiomyomas. | |

Health C for D and R. UPDATE: The FDA recommends performing contained morcellation in women when laparoscopic power morcellation is appropriate. FDA. Published online December 23, 2020. Accessed January 28, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/safety-communications/update-fda-recommends-performing-contained-morcellation-women-when-laparoscopic-power-morcellation. | |

Vargas MV, Cohen SL, Fuchs-Weizman N, et al. Open power morcellation versus contained power morcellation within an insufflated isolation bag: comparison of perioperative outcomes. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2015;22(3):433–8. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2014.11.010. | |

Winner B, Porter A, Velloze S, et al. Uncontained Compared With Contained Power Morcellation in Total Laparoscopic Hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol 2015;126(4):834–8. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000001039. | |

Meuleman C, Tomassetti C, D’Hoore A, et al. Surgical treatment of deeply infiltrating endometriosis with colorectal involvement. Hum Reprod Update 2011;17(3):311–26. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmq057. | |

Nisolle M, Brichant G, Tebache L. Choosing the right technique for deep endometriosis. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2019;59:56–65. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2019.01.010. | |

Adamson GD, Pasta DJ. Endometriosis fertility index: the new, validated endometriosis staging system. Fertil Steril 2010;94(5):1609–15. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.09.035. | |

Daraï E, Cohen J, Ballester M. Colorectal endometriosis and fertility. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2017;209:86–94. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.05.024. | |

Ballester M, Roman H, Mathieu E, et al. Prior colorectal surgery for endometriosis-associated infertility improves ICSI-IVF outcomes: results from two expert centres. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2017;209:95–9. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.02.020. | |

Falcone T, Flyckt R. Clinical Management of Endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol 2018;131(3):557–71. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000002469. | |

Carter JE. Combined hysteroscopic and laparoscopic findings in patients with chronic pelvic pain. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 1994;2(1):43–7. doi:10.1016/s1074-3804(05)80830-8. | |

Balasch J, Creus M, Fábregues F, et al. Visible and non-visible endometriosis at laparoscopy in fertile and infertile women and in patients with chronic pelvic pain: a prospective study. Hum Reprod Oxf Engl 1996;11(2):387–91. doi:10.1093/humrep/11.2.387. | |

Daniilidis A, Angioni S, Di Michele S, et al. Deep endometriosis and infertifity: What is the impact of surgery? J Clin Med 2022;11:6727 | |

Becker CM, Bokor A, Heikinheimo O, et al. ESHRE guideline:endometriosis evidence of the relationship and implications. Hum Reprod Update 2005;11:595-606 | |

Fauconnier A, Chapron C. Endometriosis and pelvic pain: epidemiologica; evidence of the relationship and implications. Hum Reprod Update 2005;11:595-606 | |

Vercellini P, Fedele L, Aimi G, et al. Association between endometriosis stage, lesion type, patient characteristics and severity of pelvic pain symptoms: a multivariate analysis of over 1000 patients. Hum Reprod Oxf Engl 2007;22(1):266–71. doi:10.1093/humrep/del339. | |

Hsu AL, Sinaii N, Segars J, et al. Relating Pelvic Pain Location to Surgical Findings of Endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol 2011;118(2 Pt 1):223–30. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e318223fed0. | |

Ferrero S, Alessandri F, Racca A, et al. Treatment of pain associated with deep endometriosis: alternatives and evidence. Fertil Steril 2015;104(4):771–92. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.08.031. | |

Daraï E, Dubernard G, Coutant C, et al. Randomized Trial of Laparoscopically Assisted Versus Open Colorectal Resection for Endometriosis: Morbidity, Symptoms, Quality of Life, and Fertility. Ann Surg 2010;251(6):1018–23. doi:10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181d9691 d. | |

Thomassin I, Bazot M, Detchev R, et al. Symptoms before and after surgical removal of colorectal endometriosis that are assessed by magnetic resonance imaging and rectal endoscopic sonography. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004;190(5):1264–71. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2003.12.004. | |

Darai E, Ackerman G, Bazot M, et al. Laparoscopic segmental colorectal resection for endometriosis: limits and complications. Surg Endosc 2007;21(9):1572–7. doi:10.1007/s00464-006-9160-1. | |

Dubernard G, Rouzier R, David-Montefiore E, et al. Use of the SF-36 questionnaire to predict quality-of-life improvement after laparoscopic colorectal resection for endometriosis. Hum Reprod 2008;23(4):846–51. doi:10.1093/humrep/den026. | |

Roman H. A national snapshot of the surgical management of deep infiltrating endometriosis of the rectum and colon in France in 2015: A multicenter series of 1135 cases. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod 2017;46(2):159–65. doi:10.1016/j.jogoh.2016.09.004. | |

Roman H, Milles M, Vassilieff M, et al. Long-term functional outcomes following colorectal resection versus shaving for rectal endometriosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016;215(6):762.e1–9. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2016.06.055. | |

Chapron C, Fauconnier A, Vieira M, et al. Anatomical distribution of deeply infiltrating endometriosis: surgical implications and proposition for a classification. Hum Reprod 2003;18(1):157–61. doi:10.1093/humrep/deg009. | |

Quintairos R de A, Brito LGO, Farah D, et al. Conservative versus radical surgery for women with deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE): systematic review and metanalysis of bowel function. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2022;0(0). doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2022.09.551. | |

Possover M, Stöber S, Plaul K, et al. Identification and preservation of the motoric innervation of the bladder in radical hysterectomy type III. Gynecol Oncol 2000;79(2):154–7. doi:10.1006/gyno.2000.5919. | |

Dubernard G, Rouzier R, David-Montefiore E, et al. Urinary Complications After Surgery for Posterior Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis are Related to the Extent of Dissection and to Uterosacral Ligaments Resection. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2008;15(2):235–40. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2007.10.009. | |

Possover M. Pathophysiologic explanation for bladder retention in patients after laparoscopic surgery for deeply infiltrating rectovaginal and/or parametric endometriosis. Fertil Steril 2014;101(3):754–8. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.12.019. | |

Armengol-Debeir L, Savoye G, Leroi AM, et al. Pathophysiological approach to bowel dysfunction after segmental colorectal resection for deep endometriosis infiltrating the rectum: a preliminary study. Hum Reprod 2011;26(9):2330–5. doi:10.1093/humrep/der190. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards programme CLICK HERE)