This chapter should be cited as follows:

Nau C, Esposito MA, et al., Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.415763

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Obstetrics Module

Volume 8

Maternal medical health and disorders in pregnancy

Volume Editor:

Dr Kenneth K Chen, Alpert Medical School of Brown University, USA

Originating Editor: Professor Sandra Lowe

Chapter

Mirror Syndrome

First published: August 2021

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

INTRODUCTION

John William Ballantyne first described the association of maternal edema in a pregnancy complicated by fetal hydrops in 1892.1 The development of maternal edema was described as having “mirrored” that of the fetus. Since this time, multiple names have been used to describe this phenomenon, including Ballantyne’s syndrome, pseudotoxemia, acute second trimester gestosis, maternal hydrops syndrome, and triple edema (fetal, placental, maternal). The term “mirror syndrome” was coined by O’Driscoll in 1956.2,3,4,5 Though mirror syndrome was originally described in the setting of Rhesus alloimmunization, it was subsequently noted to occur more generally in fetal hydrops arising from a wide range of etiologies including twin–twin transfusion syndrome, viral infections, placental tumors, metabolic disorders, fetal tumors, fetal vascular malformations, and fetal tachycardia.5,6,7 While a relatively rare condition, it is nevertheless an important consideration in pregnancies complicated by fetal hydrops.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The exact mechanism of mirror syndrome has not been fully elucidated, though its underlying pathophysiology appears to have some overlap in molecular pathways identified in pre-eclampsia, explaining the similar clinical presentation and severity.8,9 Dysregulation of placenta-mediated angiogenic and antiangiogenic factors leading to uteroplacental ischemia appears to play an etiologcal role in the development of pre-eclampsia10,11,12,13,14,15 and many of these same factors, including soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1, soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1, activin A, folistatin, endothelin-1, intercellular adhesion molecule-1, vascular adhesion molecule-1, and placental growth factor also appear to play a role in the development of mirror syndrome.9,16,17

Unlike in pre-eclampsia, however, improvement in fetal status (with appropriate fetal intervention) can enhance trends in maternal angiogenic markers.16,18 These observations imply that while pre-eclampsia and mirror syndrome share some similar molecular pathways, the inciting event leading to this dysregulation likely arises from separate causes. This is supported by the findings that placental changes associated with pre-eclampsia, such as failure of normal spiral artery remodeling, atherosis, decidual necrosis, and thrombosis, are not uniformly identified in patients with mirror syndrome. Rather, the primary finding in mirror syndrome is one of villous edema.9,17,19,20 It has been proposed that villous edema may lead to trophoblast villous hypoxia, resulting in the acute and potentially reversible release of placental-mediated factors.17

The maternal cardiovascular changes in mirror syndrome also appear to be distinct from pre-eclampsia. Women with mirror syndrome often present with anemia and evidence of increased (rather than decreased) intravascular volume.5 Echocardiography performed in two women with mirror syndrome demonstrated evidence of hyperdynamic left ventricular function in the setting of fluid overload and low systemic vascular resistance. Such findings are less commonly seen in pre-eclampsia.21,22,23 Additionally, levels of serum aldosterone are more commonly increased in mirror syndrome, in contrast to women with pre-eclampsia where plasma aldosterone levels are generally decreased. This suggest that the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system is differentially affected by these two conditions.4,21,22,24

Finally, it would appear that the presence of fetal hydrops itself, rather than the cause of fetal hydrops, is important for the development of mirror syndrome because mirror syndrome has been seen in the presence of a variety of conditions resulting in hydrops.5

Clinical Presentation and Prevalence

The clinical presentation of mirror syndrome shares many similarities with pre-eclampsia. Women may present with fetal hydrops and a combination of new-onset edema, hypertension, and proteinuria.5 Maternal findings may also include headache, vision changes, oliguria, and pulmonary edema. Laboratory evaluation may reveal abnormal renal function, elevated liver enzymes, elevated uric acid, and thrombocytopenia.5,7,25 As noted previously, a key distinguishing feature of mirror syndrome from pre-eclampsia is the presence of hemodilution and anemia as opposed to hemoconcentration, which is typically seen in severe pre-eclampsia.4,5

The prevalence of mirror syndrome has been reported as affecting 5–29% of pregnancies complicated by fetal hydrops.25,26 This variation is likely due to a combination of factors including varying diagnostic criteria, potential misclassification of mirror syndrome as pre-eclampsia, as well as the likelihood that mild cases may go unrecognized and, therefore, unreported. In one series the median time from diagnosis of hydrops to the presentation of maternal symptoms was 11.5 days.26

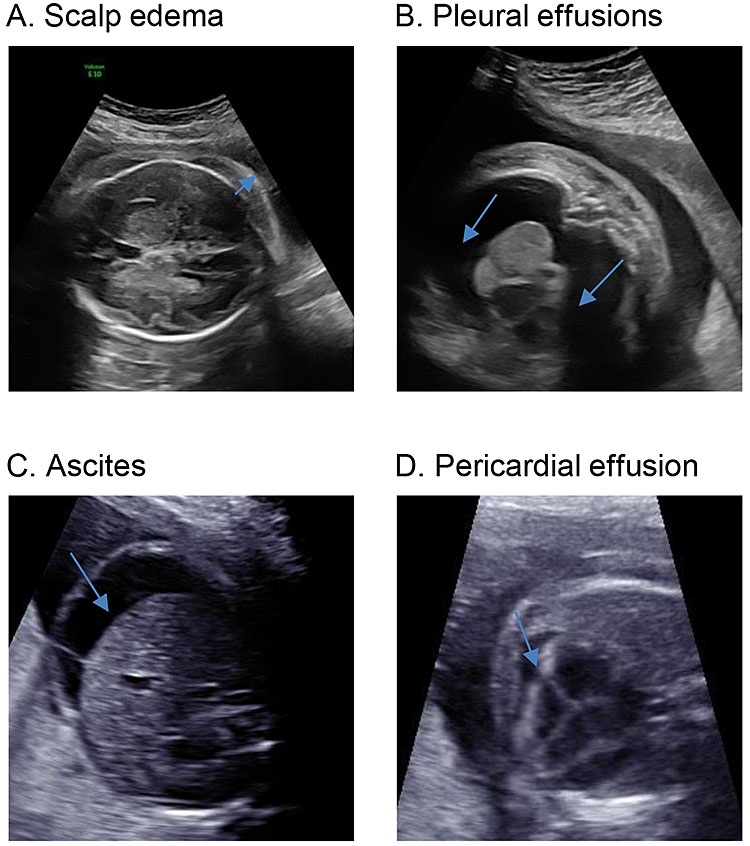

The diagnostic criteria of mirror syndrome have been variously described. The presence of fetal hydrops is required. This is commonly defined as the abnormal collection of fluid in at least two locations in the fetus including ascites, pleural effusion, pericardial effusion, and/or skin edema (thickness >5 mm) (Figure 1). Polyhydramnios and placental thickening are often seen though are not included as diagnostic criteria.27,28,29 Maternal criteria for the diagnosis of mirror syndrome appear to be less uniform, with some authors describing mirror syndrome in the setting of a rapid increase in weight gain and generalized edema while others have required a pre-eclampsia-like set of clinical findings in order to make the diagnosis.5,25,26 In one review by Braun et al., 90% of women presented with edema, 60% with hypertension, 46% with anemia, and 40% with proteinuria, with other findings being less common (Table 1). Thus, while discrete maternal diagnostic criteria are ill-defined, the presence of mirror syndrome should be considered when fetal hydrops is noted with any of the maternal findings listed above.

1

Sonographic findings in fetal hydrops: (A) the arrow indicates the elevation of the fetal skin away from the fetal scalp (bony rim is bright white); (B) arrow indicates bilateral pleural effusions; (C) arrow shows a rim of ascites around the fetal liver; (D) arrow demonstrates a pericardial effusion.

1

Common presenting signs in mirror syndrome5 (with permission).

Maternal symptoms | Percentage (%) of patients |

Weight gain and edema | 89.3 |

Hypertension | 60.7 |

Anemia/hemodilution | 46.4 |

Albuminuria and proteinuria | 42.9 |

Elevated liver enzymes | 19.6 |

Oliguria | 16.1 |

Headache/vision changes | 14.3 |

MANAGEMENT AND PROGNOSIS

The management of mirror syndrome is challenging because it often requires a careful balance between the maternal and fetal risks of delivery as compared with those incurred by continued expectant management. Considerations include the underlying etiology of fetal hydrops, fetal status, gestational age, as well as the severity of maternal illness. Due to the complexity and rarity of mirror syndrome, as well as the significant maternal and fetal risks, management is best undertaken at a tertiary care center with an obstetric team that has experience in the management of complicated pregnancy and with the resources to allow for preterm delivery as well as maternal supportive care.

The etiology of fetal hydrops is of critical importance, and attempts should be made to determine the underlying cause. While the diagnostic evaluation of a fetus with hydrops is beyond the scope of this article, diagnostic tests may include the following: detailed sonographic evaluation (fetus, umbilical cord, and placenta), fetal echocardiogram, middle cerebral artery Doppler studies, determination of maternal Rh status, evaluation for maternal alloimmunization, maternal complete blood count, Kleihauer–Betke stain, serologic studies for syphilis, parvovirus B19, cytomegalovirus and toxoplasmosis, and fetal karyotype.27 If a reversible etiology is identified, and the maternal and fetal status is stable, then attempts can be made to treat the underlying cause of hydrops (e.g. intrauterine blood transfusion for fetal anemia, maternal transplacental treatment of antiarrhythmics for fetal tachycardia etc.). Successful interventions to resolve fetal hydrops have resulted in resolution of the maternal symptoms of mirror syndrome.26,30,31,32,33,34,35

In cases with evidence of significant maternal or fetal compromise or for those cases in which a treatable etiology for fetal hydrops is not found, delivery is typically indicated.27 Though expectant management can be considered in certain circumstances (e.g. severe prematurity), this must be undertaken with specific counseling regarding both the maternal and fetal risks as well as the diagnostic ambiguity inherent in distinguishing mirror syndrome from pre-eclampsia. The risk of severe maternal morbidity in mirror syndrome has been reported to be as high as 21%, with pulmonary edema being the most common severe complication. In one series describing expectant management of mirror syndrome, the median duration of pregnancy latency was 4.5 days before delivery was indicated due to maternal or fetal deterioration.26 If expectant management is elected, close monitoring of maternal status and antepartum fetal surveillance is warranted, as well as administration of corticosteroids for fetal lung maturity, if appropriate. Once the decision has been made to proceed with delivery, it is reasonable to attempt vaginal delivery unless this is precluded by maternal or fetal status.

With delivery (or resolution of fetal hydrops), maternal prognosis is typically good with resolution of maternal symptoms requiring an average of 2–9 days.5,26 Fetal and neonatal outcomes are more variable and are related to the gestational age at diagnosis, preterm delivery, and the underlying pathology resulting in fetal hydrops.5,26,36

The risk of recurrence in a subsequent pregnancy is unknown, and it is likely related to the risk of recurrence of fetal hydrops which varies based on underlying etiology. Because mirror syndrome is a rare entity, it is likely that the overall recurrence risk is probably low. Pre-eclampsia is associated with an increase in cardiovascular and hypertensive disease in later life;37,38,39,40 however, there is a paucity of data to evaluate whether this also holds true for women who have had a pregnancy complicated by mirror syndrome.

CONCLUSION

Mirror syndrome is a rare, though important, clinical entity that can occur in a pregnancy complicated by fetal hydrops. Its presentation often mimics pre-eclampsia, requiring a low index of suspicion when managing such pregnancies. A key clinical feature distinguishing mirror syndrome from pre-eclampsia is maternal hemodilution (vs. hemoconcentration, as commonly seen with pre-eclampsia). Maternal symptoms can be reversed if the underlying condition resulting in fetal hydrops can be treated. In cases with unremitting fetal hydrops, progressive worsening of maternal status often requires delivery. Resolution of maternal symptoms typically occurs rapidly following delivery or with treatment of fetal hydrops. Management of such pregnancies should include medical providers with experience in caring for complicated pregnancies and with resources allowing for potential preterm delivery and maternal supportive care.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- Women with pregnancy complicated by fetal hydrops should be monitored for the development of mirror syndrome.

- If mirror syndrome is diagnosed or suspected, pregnancy management should occur at a tertiary care center with an obstetric team that has experience in the management of complicated pregnancy and with the resources to allow for both preterm delivery and maternal supportive care.

- Fetal evaluation should occur to identify the underlying etiology of hydrops. If possible, antenatal therapy to reverse fetal hydrops should be considered as this may lead to resolution of maternal disease.

- Expectant management may be considered if stable maternal and fetal status permits and continuing pregnancy is felt to confer benefit (e.g. extreme prematurity). However, this should include close monitoring and delivery should occur promptly for worsening maternal or fetal status.

- If preterm delivery is planned or anticipated, administration of antenatal corticosteroids should be considered.

- Due to the clinical overlap of mirror syndrome with pre-eclampsia, magnesium sulfate administration peripartum for seizure prophylaxis should be considered.

- In the absence of other clinical or obstetric factors, attempted vaginal delivery is generally preferred.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) of this chapter declare that they have no interests that conflict with the contents of the chapter.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

REFERENCES

Ballantyne JW. The Disease and Deformities of the Fetus. Edinburgh: Oliver & Boyd, 1892. | |

O’Driscoll DT. A fluid retention syndrome associated with severe isoimmunisation to the Rhesus factor. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Emp 1956;63:372–4. | |

van Selm M, Kanhai HH, Gravenhorst JB. Maternal hydrops syndrome: a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv 1991;46:785–8. | |

Carbillon L, Oury JF, Guerin JM, et al. Clinical biological features of Ballantyne syndrome and the role of placental hydrops. Obstet Gynecol Surv 1997;52:310–14. | |

Braun T, Brauer M, Fuchs I, et al. Mirror syndrome: a systematic review of fetal associated conditions, maternal presentation and perinatal outcome. Fetal Diagn Ther 2010;27:191–203 | |

Potter EL. Rh, Its Relation to Congenital Hemolytic Disease & to Intragroup Transfusion Reactions. Chicago: The Year Book Publishers Inc., 1947:146–7. | |

Allarakia S, Khayat HA, Karami MM, et al. Characteristics and management of mirror syndrome: a systematic review (1956–2016). J Perinat Med 2017;45(9):1013–21. | |

Gherman RB, Incerpi MH, Wing DA, et al. Ballantyne syndrome: is placental ischemia the etiology? J Matern Fetal Med 1998;7(5):227–9. | |

Hobson SR, Wallace EM, Chan YF, et al. Mirroring preeclampsia: the molecular basis of Ballantyne syndrome. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2019:1–6. PMID: 30614331. | |

Levine RJ, Lam C, Qian C, et al. Soluble endoglin and other circulating antiangiogenic factors in preeclampsia. CPEP Study Group [published erratum appears in N Engl J Med 2006;355:1840]. N Engl J Med 2006;355:992–1005. | |

Chaiworapongsa T, Espinoza J, Gotsch F, et al. The maternal plasma soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 concentration is elevated in SGA and the magnitude of the increase relates to Doppler abnormalities in the maternal and fetal circulation. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2008;21:25–40. | |

Crispi F, Dominguez C, Llurba E, et al. Placental angiogenic growth factors and uterine artery Doppler findings for characterization of different subsets in preeclampsia and in isolated intrauterine growth restriction. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006;195:201–7. | |

Nagamatsu T, Fujii T, Kusumi M, et al. Cytotrophoblasts up-regulate soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 expression under reduced oxygen: an implication for the placental vascular development and the pathophysiology of preeclampsia. Endocrinology 2004;145:4838–45. | |

Nevo O, Soleymanlou N, Wu Y, et al. Increased expression of sFlt-1 in in vivo and in vitro models of human placental hypoxia is mediated by HIF-1. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2006;291:R1085–93. | |

Espinoza J. Uteroplacental ischemia in early- and late-onset pre-eclampsia: a role for the fetus? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2012;40:373–82. | |

Goa S, Mimura K, Kakigano A, et al. Normalisation of angiogenic imbalance after intra-uterine transfusion for mirror syndrome caused by parvovirus B19. Fetal Diagn Ther 2013;34(3):176–9. doi: 10.1159/000348778. Epub 2013 May 24. | |

Espinoza J, Romero R, Nien JK, et al. A role of the anti-angiogenic factor sVEGFR-1 in the 'mirror syndrome' (Ballantyne's syndrome). J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2006;19(10):607–13. | |

Llurba E, Marsal G, Sanchez O, et al. Angiogenic and antiangiogenic factors before and after resolution of maternal mirror syndrome. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2012;40(3):367–9. | |

Kaiser IH. Ballantyne and triple edema. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1971;110:115–20. | |

Graham N, Garrod A, Bullen P, et al. Placental expression of anti-angiogenic proteins in mirror syndrome: a case report. Placenta 2012;33:528–31. | |

Umazume T, Morikawa M, Yamada T, et al. Changes in echocardiography and blood variables during and after development of Ballantyne syndrome. BMJ Case Rep 2016;bcr2016216012. | |

Suzuki Y, Yamamura M, Kikuchi K, et al. Echocardiography findings in a case with Ballantyne syndrome. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2017;43(2):387–91. | |

Simmons LA, Gillin AG, Jeremy RW. Structural and functional changes in left ventricle during normotensive and preeclamptic pregnancy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2002;283:H1627–33. | |

Verdonk K, Visser W, Van Den Meiracker AH, et al. The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in pre-eclampsia: the delicate balance between good and bad. Clin Sci (Lond) 2014;126(8):537–44. | |

Gedikbasi A, Oztarhan K, Gunenc Z, et al. Preeclampsia due to fetal non-immune hydrops: mirror syndrome and review of literature. Hypertens Pregnancy 2011;30:322–30. | |

Hirata G, Aoki S, Sakamaki K, et al. Clinical characteristics of mirror syndrome: a comparison of 10 cases of mirror syndrome with non-mirror syndrome fetal hydrops cases. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 29:16, 2630–4. | |

Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM); Mary E. Norton, MD; Suneet P. Chauhan, MD; and Jodi S. Dashe, MD. Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) Clinical Guideline #7: nonimmune hydrops fetalis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;212(2):127–39. | |

Skoll MA, Sharland GK, Allan LD. Is the ultrasound definition of fluid collections in nonimmune hydrops fetalis helpful in defining the underlying cause or predicting outcome? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 1991;1:309–12 | |

Hoddick WK, Mahony BS, Callen PW, et al. Placental thickness. J Ultrasound Med 1985;4:479–82 | |

Chimenea A, García-Díaz L, Calderón AM, et al. Resolution of maternal mirror syndrome after successful fetal intrauterine therapy: a case series. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018;18(1):85. | |

Livingston JC, Malik KM, Crombleholme TM, et al. Mirror syndrome: a novel approach to therapy with fetal peritoneal-amniotic shunt. Obstet Gynecol 2007;110:540–3. | |

Heyborne KD, Chism DM. Reversal of Ballantyne syndrome by selective second-trimester fetal termination. A case report. J Reprod Med 2000;45:360–2. | |

Heyborne KD, Porreco RP. Selective fetocide reverses preeclampsia in discordant twins. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004;191:477–80. | |

Frohn-Mulder IM, Stewart PA, Witsenburg M, et al. The efficacy of flecainide versus digoxin in the management of fetal supraventricular tachycardia. Prenat Diagn 1995;15:1297–302. | |

Simpson JM, Sharland GK. Fetal tachycardias: management and outcome of 127 consecutive cases. Heart 1998;79:576–81. | |

Czernik C, Proquitté H, Metze B, et al. Hydrops fetalis–has there been a change in diagnostic spectrum and mortality? J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2011;24:258–63 | |

Behrens I, Basit S, Melbye M, et al. Risk of post-pregnancy hypertension in women with a history of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: nationwide cohort study. BMJ 2017;358:j3078. | |

Stuart JJ, Tanz LJ, Missmer SA, et al. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and maternal cardiovascular disease risk factor development: an observational cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:224–32. | |

Brown MC, Best KE, Pearce MS, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk in women with pre-eclampsia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Epidemiol 2013;28:1–19. | |

Grandi SM, Vallee-Pouliot K, Reynier P, et al. Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy and the risk of subsequent cardiovascular disease. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2017;31:412–21. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards programme CLICK HERE)