This chapter should be cited as follows:

Domoney J, Alderdice F, Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.409553

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Obstetrics Module

Volume 7

Maternal mental health in pregnancy

Volume Editor: Professor Louise Howard, King’s College, London, UK

Chapter

Postnatal Depression

First published: February 2021

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

INTRODUCTION

Postnatal depression (PND) is a global public health problem with prevalence rates between 13 and 19%.1,2 It is defined as a major depressive disorder in the year following childbirth and is one of the most common disorders of the postnatal period.3 Risk factors include environmental, psychological and biological factors, and it is associated with a range of adverse outcomes for the woman and her child.4 Health professionals working with families in the perinatal period need to be able to identify women with PND and support them to access appropriate treatment in order to reduce the burden of this disorder on women and their families. This chapter provides details of the epidemiology and etiology of PND, as well as an overview of the evidence-base and clinical guidance for identification, prevention and intervention.

While this chapter is dedicated to postnatal depression, depression during pregnancy is also highly prevalent and is a strong risk factor for postnatal depression. Many of the risks and consequences for antenatal and postnatal depression are the same and, therefore, being able to identity and support women with depression means being aware of the symptoms both during pregnancy and in the postpartum.

Additionally, while the literature on postnatal depression has traditionally referred to maternal depression, it is increasingly recognised that men also suffer from depression during the perinatal period.5 Paternal depression is associated with adverse outcomes for the man himself, for his partner and also for his baby, and therefore this is also relevant for professionals working in this time period.

DEFINITION

Diagnostic systems

There are two internationally recognised systems for diagnosing mental disorders. These are the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edn (DSM-5)6 produced by the American Psychiatric Association, and Chapter V of the International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition (ICD-10),7 produced by the World Health Organization (WHO).

While the term ‘postnatal depression’ is widely used, DSM-5 does not classify PND as a separate diagnosis from major depression and so women must meet the same criteria as a major depressive episode to be diagnosed. The specifier ‘with peripartum onset’ may be included if the most recent episode occurs during pregnancy or in the 4 weeks following delivery (although most literature defines PND as occurring in the first postnatal year). ICD-10 does have a diagnosis code for mental disorders associated with the puerperium. However, the definition of these disorders is that they should not meet the criteria for disorders classified elsewhere, and therefore most cases of postnatal depression will be classified as major depression. Similarly to DSM-5, the specifier ‘with postnatal onset’ is used if the disorder begins within 6 weeks of delivery.

Key symptoms for diagnosis are low mood and loss of interest or pleasure in daily activities, which represents a change from normal mood. In addition, fatigue/loss of energy, changes in sleep or appetite, poor concentration, indecisiveness, feelings of worthlessness or guilt, psychomotor agitation or retardation, and suicidal thoughts also indicate a depressive episode. Symptoms should be associated with clinically significant distress or impairment in functioning and should be present most days for at least 2 weeks to fulfil criteria (see Box 1 for diagnostic criteria as defined by DSM-5). While somatic symptoms, such as changes in sleep, appetite and energy levels, are often present in non-depressed postnatal women, they are nonetheless valid indicators of PND.3 However, as detailed later, some screening measures exclude these symptoms to aid the identification of PND.

Severity

In these diagnostic systems, severity is defined by the number of symptoms and the level of impairment. For example, in ICD-10, severe depression must include at least seven symptoms present for 2 weeks, while minor depression should include at least four symptoms. In DSM-5, severe depression should include most of the symptoms listed in Box 1, with marked interference in functioning, while mild depression is defined as few, if any, symptoms in excess of the five required to make a diagnosis, and only minor functional impairment.

Box 1 Diagnostic criteria for major depressive episode (adapted from DSM-5)

- At least five symptoms present for at least 2 weeks, for most of the day

One symptom must include- Depressed mood

- Loss of interest or pleasure in daily activities

- Other symptoms

- Change in weight or appetite

- Insomnia or hypersomnia

- Psychomotor retardation or agitation

- Loss of energy or fatigue

- Worthlessness or excessive guilt

- Impaired concentration or indecisiveness

- Recurrent thoughts of death or suicidal ideation (with or without a specific plan)

- Symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment in functioning

- Symptoms are not due to substance use or medical condition, are not better explained by a psychotic disorder, and there has never been a manic or hypomanic episode

Women’s experience of postnatal depression

Women’s experience of PND has been captured in several qualitative studies.8,9 These studies help to provide a context for the symptoms described above and give some insight into the ways that social/environmental, psychological and biological factors can impact on mood at the time of having a baby.

Fear of failure runs across many studies – failing to live up to an idealized view of motherhood, comparing oneself unfavorably to others, and feeling guilty at a lack of coping. The experience of loss is also a strong theme, including loss of lifestyle as it used to be before the baby was born, loss of intimacy in relationships as all attention is given to the baby, and a sense of loss of control over one’s life. These fears and worries are experienced in the context of poor sleep, recovering physically from the birth, and changes in hormonal levels which can lead to fluctuations in mood. On top of these experiences, the stigma associated with PND is a significant stressor as women fear being labelled as a bad mother and potentially having their children removed. This can lead to reduced help-seeking meaning that often women do not receive the treatment they need.

These factors are important to hold in mind as they can impact on women’s help-seeking behavior, engagement with interventions, and relationships with health professionals.

PREVALENCE

Women have double the risk of experiencing major depression in their lifetime in comparison to men and the prevalence has been found to be higher in the reproductive years.10 In pregnancy, depression is one of the most common psychiatric disorders and is often comorbid with anxiety. A meta-analysis by Bennett et al. (2004) found prevalence rates were 7.4% for the first trimester, 12.8% for the second trimester, and 12.0% for the third trimesters.11 Postnatally, a systematic review found a prevalence estimate of postnatal depression to be 13%2 but there was high variability from study to study. Internationally, estimates vary from 1.9% to 82.1% in low- and middle-income countries and from 5.2% to 74.0% in high-income countries.12 More limited data on men in the postnatal period suggest estimates of the prevalence of paternal postnatal depression in the first 6 months postpartum vary from 4 to 25%.5,13

Variability in prevalence across studies reflects cultural differences in the experience, manifestation and disclosure of depression as well as variations in definitions, cut-offs and study methodologies. The variability also suggests there may be differences in the ways in which women respond to questions about their mental well-being.14 Misconceptions around postnatal depression are common and can lead to disadvantageous and inappropriate responses by clinicians and women themselves.15 Further complexities include the differentiation between low mood and depression, the co-existence of postnatal depression with other mental disorders such as anxiety, and the fact that many symptoms of postnatal depression such as concentration difficulties, fatigue and sleeplessness may be normal manifestations of the postnatal period.16

RISK FACTORS

One of the greatest risk factors for postnatal depression is antenatal depression or anxiety. Women with untreated depression during pregnancy have been found to be seven times more likely to experience postnatal depression compared with women with no antenatal depression.17 Therefore, screening for depressive symptoms in pregnancy as well as the postnatal period is highlighted in clinical guidance.

Many of the risk factors associated with antenatal depression are also risk factors for PND (Table 1). Social and environmental factors such as low social support, negative life events, domestic violence, previous abuse, low partner support, and marital difficulties are all associated with perinatal depression, along with low socioeconomic status and migration status. A history of depression or family history of psychiatric illness are also risk factors,4 and there is some evidence that obstetric complications and unwanted pregnancy are also associated with PND. This evidence highlights the importance of women’s environment and sense of safety in the onset of PND, as well as giving an indication of potential targets for prevention and intervention.

Additional risk factors in the postnatal period include breastfeeding and sleep deprivation. A systematic review by Dias and Figueiredo18 found that while there is an association between depression and shorter duration of breastfeeding the direction of the relationship is unclear. Some studies suggest exclusive breastfeeding is protective for postnatal depression,19 while others suggest women who breastfeed for a longer time have a higher risk of depression.20 More disturbed infant sleep and more frequent feeding has been associated with higher depression symptoms postpartum.21,22

There is a moderate correlation between depression in fathers and mothers.13 Kim and Swain23 suggest two main groups of factors associated with risk of depression in men around the time of birth: biological and ecological. Changes in hormones, including testosterone, estrogen, cortisol, vasopressin, and prolactin, during the postnatal period in fathers have been suggested as biological risk factors in paternal PND. However, the data are limited and so should be interpreted with caution. In terms of social/environmental risk factors, these are very similar to those found in women, e.g. low partner support and marital difficulties, and a history of depression or anxiety either before or during pregnancy. Additionally, being unemployed and feeling excluded from the bonding process are risk factors for men.24

1

Key risk factors for postnatal depression in women.

Social and environmental risk factors | Psychological risk factors | Biological risk factors |

Domestic violence | Depression in pregnancy | Chronic illness or medical illness |

Previous abuse | Anxiety in pregnancy | Preterm birth, low birth weight |

Low social support | History of depression | Multiple births |

Low partner support, marital difficulties | Substance misuse | |

Negative life events | Family history of psychiatric illness | |

Migration status | ||

Low socioeconomic status |

OUTCOMES

Similarly to depression at other times of life, PND is associated with reduced functioning across social, occupational and educational domains, as well as impacting negatively on relationships and leading to personal suffering.

The report ‘Saving Lives, Improving Mothers' Care’25 produced by the MBRRACE-UK collaboration (Mothers and Babies: Reducing Risk through Audits and Confidential Enquiries across the UK) states that maternal suicide is the leading cause of death in the postnatal period, with 1 in 7 women who die in the period between 6 weeks and 1 year after pregnancy dying by suicide. Risk can increase rapidly in the perinatal period and, therefore, the report states that there are multiple opportunities to reduce women’s risk through early and forward planning of women with known pre-existing mental health problems. This highlights the need to identify at-risk women early and offer appropriate support throughout the perinatal period to reduce the likelihood of poor outcomes.

PND also has an impact on women’s close relationships: having a baby is associated with a decrease in marital satisfaction26 and there is a moderate correlation between maternal and paternal depression13 with this co-occurrence being associated with deterioration in the couple relationship.

Additionally, PND has been found to have an adverse impact on a range of developmental outcomes in children. This includes cognitive functioning, behavioral problems, and social-emotional development. Where studies have followed up children over long periods of time, effects have been shown to persist into adolescence.27 Importantly, poor outcomes for children are also associated with antenatal depression, independently of the effects of PND, further underlining the need to identify women early in the perinatal period to reduce adverse impacts.28

Postnatally, a key mechanism for the transmission of risk is parent–infant interaction. Postnatal depression has been found to have a moderate to large effect on the quality of interactions, including impacting negatively on the mother’s ability to respond appropriately to infant cues or alleviate infant distress, reducing enjoyment in the interaction, and leading to less engagement in joint activities.29 Depressed mothers have also been noted to touch their infants less, show fewer signs of overt affection, and have less responsive speech.30

In addition to these impacts on interactions, there is some evidence that PND has a negative impact on care-giving routines such as sleeping and feeding practices (although as noted earlier there are likely to be bi-directional effects, e.g. infants who have difficulty feeding and sleeping may increase symptoms of PND), and that women with PND are less likely to attend maternal and child health appointments.31

However, not all women who suffer from PND will have children who go on to show poorer outcomes. Women with PND who are also experiencing social adversity are more likely to have low levels of responsiveness to their infants32 and severe, persistent symptoms of depression are the most likely to impact on outcomes.33

Furthermore, the wider social environment influences child outcomes. For example, early relationships with non-depressed adults may buffer the child against any adverse impacts from PND,34 while paternal depression is associated with poorer child outcomes, over and above maternal effects.35 The quality of the couple relationship is also an important factor as couple conflict has been found to mediate the relationship between parental depression and infant outcomes, as well as acting as an independent risk.36 Therefore, when identifying and supporting women with PND, assessment should take into account the wider social environment to ensure that interventions can target a range of factors.

IDENTIFICATION

All women in the perinatal period should be assessed for depressive symptoms. As many women do not have contact with mental health professionals, other health professionals who work with women before and after birth need to be able to identify symptoms and provide appropriate support and referral.

Assessment often involves administering a validated tool to identify people who may be experiencing a mental health disorder. This is not the same as diagnosis, and those whose score indicates possible disorder should be offered further assessment. Where practitioners have systems in place for identifying PND, this should include adequate staff training, appropriate referral pathways, and availability of effective treatments to reduce symptoms. This is necessary as there are potential harms associated with identifying PND including increased distress from being asked, stigma associated with positive identification and the possibility of misusing symptom measures as diagnostic instruments.37

The most widely used instrument to identify postnatal depression is the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS).38 This is a 10-item self-report instrument which includes statements about depressive symptoms experienced in the past week, including depressed mood, anhedonia, anxiety and self-harm. Responses are rated from 0 to 3 according to severity, which provides an overall score out of a maximum of 30. The EPDS excludes somatic symptoms which are common in the postnatal period, such as changes in appetite, sleep and energy levels. It has been translated into several non-English languages and has been validated in men and also in the antenatal period.

The most frequently used cut-off score for the EPDS is greater than or equal to 13. However, the positive predictive value (the probability that women who screen positive truly have depression) of the EPDS has been estimated to be around 50–60%,39,40 highlighting the need for further assessment following a positive screen.

A number of other generic, self-report instruments can also be used in the identification of PND. However, in contrast to the EPDS, there have been relatively few validation studies of other instruments to identify PND and therefore it is difficult to draw firm conclusions about their utility in the perinatal period. Three of the more widely used instruments are the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9),41 the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II)42 and the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ).43 The PHQ-244 can also be used. This consists of the first two PHQ-9 items: “Over the last two weeks, how often have you been bothered by (1) feeling down, depressed or hopeless or (2) having little interest or pleasure in doing things?”. These questions can also be used with a yes/no response as opposed to the original likert scale, and are then referred to as the Whooley questions.45

Guidelines for identification

Guidelines for identifying perinatal depression vary across countries, although all include the need for further assessment and follow-up where women screen positive. Note that guidance refers to either ‘perinatal’ screening or specifies both antenatal and postnatal screening, indicating the need to be aware of symptoms of depression during pregnancy as well as postpartum. Some examples of guidance are described here.

- In the UK15 it is recommended to ask women about possible depression at their first contact with primary care during pregnancy and again at every contact, including during the early postnatal period, using the Whooley questions (PHQ-2).44 This recommendation has recently been supported by evidence showing that it is effective in identifying depression and is also a marker for other disorders.46 If a woman responds positively to either of the questions, health professionals are advised to use the EPDS or an alternative questionnaire (PHQ-9) as part of a full assessment or refer the woman to her general practitioner or a mental health professional.

- In Australia47 it is recommended to use the EPDS to screen women for a possible depressive disorder as early as practical in pregnancy, with repeat screening at least once later in pregnancy. In addition, it is recommended to screen 6–12 weeks after birth, with repeat screening at least once in the first postnatal year. Women with a score between 10 and 12 should be monitored with repeat screening 2–4 weeks later, and women with an EPDS score of 13 or more should undergo further assessment.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists48 recommends screening women for depressive symptoms at least once during the perinatal period using a validated tool. The guidance states that appropriate follow-up and treatment should be offered when indicated.

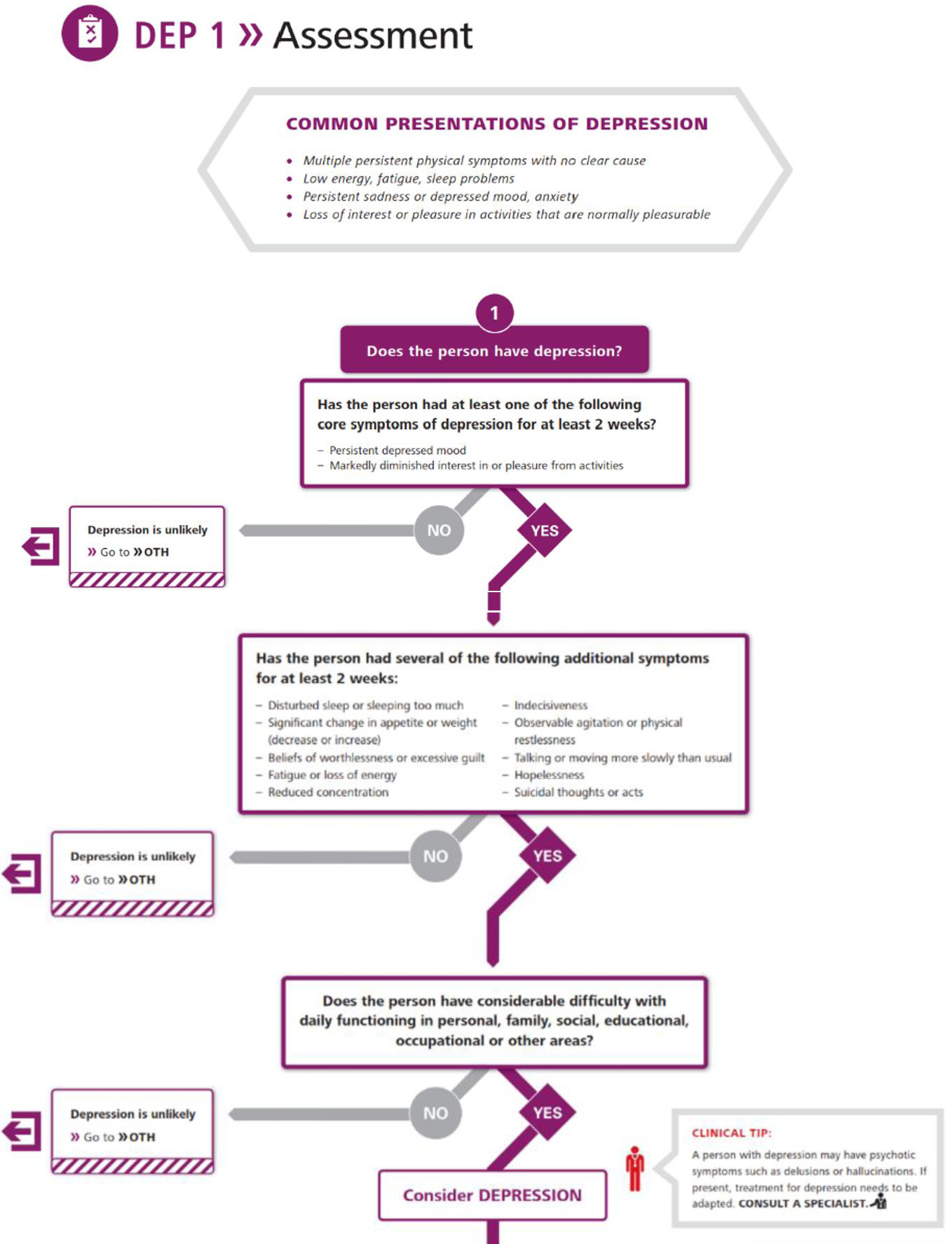

- The World Health Organization’s Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) has developed a technical tool, the mhGAP Intervention Guide,49 to provide guidance on the integrated management of a range of disorders. While it does not specify tools or procedures for identifying PND, it provides a flow chart for identifying depression which is based on criteria from ICD-10 (Figure 1).

1

World Health Organization flow chart for identifying depression. (Reproduced with permission from the World Health Organization.)

While guidelines vary slightly regarding recommendations on tools to use, there are a number of key principles of care when identifying women with PND, which include:

- Involving women in decisions about their care and ensuring that women are given the chance to discuss treatment options and understand the risks and benefits of these;

- Providing culturally relevant information;

- Ensuring an integrated care plan which sets out the roles and responsibilities of all healthcare professionals who are involved;

- Where possible, providing continuity of care;

- Ensuring adequate time to assess and listen with empathy and respect.

To adhere to these principles, health professionals working with women in the perinatal period need adequate training and support to understand how to identify PND and provide appropriate treatments. One such training tool has been developed by the Perinatal Education Programme (PEP) in South Africa, a non-profit organization which aims to improve the care of pregnant women and their infants, especially in poor, rural communities. The tool can be accessed online at https://bettercare.co.za/learn/maternal-mental-health/text/0-3-contents.html.

Differential diagnosis

Women may present with changes in mood in the postnatal period for a variety of reasons and so it is important to differentiate these. In particular, depression and anxiety are highly co-morbid in the postnatal period, with around one in 12 women having co-morbid symptoms.50 Therefore, professionals need to be aware of this as treatments for anxiety differ from those for depression.

Women and health professionals often use the term ‘baby blues’ to refer to a minor mood disturbance which usually develops within 2–3 days of birth with a peak around the 5th day and resolves within 2 weeks. This may include mood swings, tearfulness, irritability and anxiety, but in general hopelessness and worthlessness are not prominent, care of the baby is not impaired, and there is no suicidal ideation.

Postnatal psychosis is a psychiatric emergency and refers to the acute onset of a manic or depressive psychosis soon after birth. Over 90% of women with postnatal psychosis experience onset in the first postnatal week (73% by day 3)51 and this can rapidly develop into a severe condition which significantly increases the risk of harm to the mother and baby (see chapter on Postpartum psychosis in this volume).

PREVENTION

Women are often in contact with health professionals throughout their pregnancy and the key risk factors for PND are well-established. Therefore, there is a unique opportunity for prevention of PND and there has been substantial interest in this in the literature.

Prevention efforts may be universal, i.e. target populations who are not at increased risk for PND, or indicated, i.e. target women who have risk factors for PND and/or above average scores on screening measures, but who do not meet diagnostic criteria.

Psychosocial and psychological

A systematic review and evidence synthesis of global studies looking at the effectiveness of interventions to prevent PND found a range of interventions to be potentially useful.52 However, it should be noted that evidence for these interventions often relies on a small number of studies with limited long-term follow up.

In terms of universal interventions, two types of intervention appeared to be beneficial in preventing PND. The first of these was midwifery redesigned postnatal care. This refers to a service led by midwives, with continuity of care and involvement of women, which is supportive and sensitive to individual needs and preferences and includes a focus on the identification and management of women’s physical and psychological health needs. This model of care was tested in a UK setting53 and is aligned with some of the recommendations in the practice guidelines for screening described above. This highlights the importance of service structures and midwifery practices in preventing PND.

The second universal intervention found to be beneficial was postnatal sessions delivered by health visitors (UK maternal and child health nurses) using psychologically informed practices. In particular, a person-centered approach (PCA) and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)-based intervention were beneficial. PCA is based on the idea that the opportunity to explore difficulties with someone who is non-judgemental and empathic allows the individual to feel validated and this supports their ability to manage distress and find their own solutions to difficulties. CBT is based on the idea that thoughts, feelings and behaviors are linked in predictable ways and that by understanding these patterns, particularly those that lead to distress, individuals can make changes and test out new ways of thinking and behaving. These were both manualized approaches delivered across up to eight sessions by non-mental health specialists whose role is to support women and their infants postnatally. The control group received usual care by health visitors. These studies suggest that intensive professional postnatal support which includes psychologically informed input may be beneficial in preventing PND.

These universal interventions rely upon a high level of resources and structure in maternity and postnatal care and therefore may be challenging to deliver in some settings. Many studies have therefore targeted women with risk factors for PND.

Where women score highly on screening measures and have additional risk factors for PND, a range of interventions have been found to be beneficial.52 In particular, psychosocial interventions such as education on preparing for parenting (classes in pregnancy and the postpartum, focusing on both physical and emotional preparation for parenthood),54 and promoting parent–infant interaction (home visits by postnatal nurses to enhance maternal sensitivity and responsiveness to infant signals as well as encouragement to express feelings),55 appear to be helpful. Psychological therapies have also been found to be beneficial. This includes those described previously (PCA-based intervention and CBT-based intervention) as well as interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT). IPT emphasizes enhancing social support and strengthening social relationships, both of which are known to be factors related to PND, and a meta-analysis suggests it has greater effect sizes for reducing symptoms of PND than other psychological therapies.56 Similarly, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of family therapeutic interventions57 found that these were effective in the prevention and treatment of perinatal depression. These interventions address co-parenting, couple relational dynamics, or dynamics involving extended family members in order to make changes in relationship functioning.

The range of interventions found to be helpful in preventing PND is indicative of the many factors which impact on mood in the perinatal period and suggests that there is some flexibility in the strategies used in different settings to support women. In particular, the effectiveness of interventions which focus on social relationships indicates how important social support and good quality relationships are for perinatal women.

A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies investigating women’s experience of preventive interventions for PND found that the key mechanisms perceived by women as helpful were support and empowerment.58 In particular, emotional and informational support in the form of sharing experiences with other women, exchanging advice, and having a good relationship with healthcare professionals were important. In terms of empowerment, having sufficient information and feeling well-prepared, including being taught practical strategies for managing difficulties and having active participation in their own care, were seen as important.

See Box 2 for a summary of useful preventive strategies.

Box 2 What is useful to prevent PND?

- Midwifery led care which is individualized and focuses on women’s needs, including a good relationship with healthcare professionals and active participation in their own care.

- Education on preparing for parenthood – information about the transition, practical strategies for managing difficulties, exchanging advice with other women.

- Intensive professional postnatal support which includes psychologically informed input.

- Promoting parent–infant interaction.

- Psychological therapies, in particular, interpersonal therapy.

- Family therapeutic interventions which address social relationships.

Pharmacological

There are limited data on the use of pharmacological treatments for the prevention of PND and a recent review which aimed to assess the effectiveness of antidepressant medication for this use concluded that it was not possible to draw any clear conclusions.59 Importantly, women may be reluctant to take medication when they are breastfeeding and may also worry about other side-effects, such as impacts on interaction with their infant.60 Therefore, there is a lower threshold for access to psychological therapies or other forms of prevention during the perinatal period.

INTERVENTION

For women who meet the criteria for PND, treatment choice will depend on several factors including the preference of the woman, the availability of psychological therapies, the severity of the illness, the risks involved and, in the case of pharmacological therapy, whether the woman is breastfeeding. Practitioners need to hold in mind that maternal suicide is the leading cause of death in the postnatal period and is associated with lack of active treatment. Therefore, it is important to offer prompt intervention and support women to adhere to treatment.

Psychosocial and psychological interventions

Similarly to preventive efforts, there is often a lower threshold for psychological therapies for the treatment of PND as women may be reluctant to take medication. A systematic review61 and meta-analysis62 found that a number of psychosocial and psychological interventions are effective in reducing symptoms of depression in the first postnatal year. This includes telephone-based peer support (mother-to-mother), non-directive counselling in the context of home visits, and also psychological therapies such as CBT, IPT and psychodynamic psychotherapy. Additionally, a recent review found that internet-based cognitive behavior therapy with therapist support was effective in reducing symptoms of PND.63

Given the impact of PND on child developmental outcomes, the effectiveness of interventions on these outcomes is also an important issue. A review of the effect of perinatal depression treatment on parenting and child development in high income countries (HICs)29 found that maternal–child interaction guidance and psychotherapeutic group support were effective in improving some aspects of parenting, while IPT and CBT showed promising but non-significant effects.

Important caveats of this literature are that most trials are short-term and so longer-term outcomes of these treatments remain unknown. Additionally, screening measures (as opposed to diagnostic interviews) are often used to determine the target population in intervention trials. These measures will identify more women than diagnostic interviews, including those who would not meet criteria for a major depressive episode. This can make it harder to identify who benefits from different treatments. Finally, there are currently not enough data to compare the effects of these interventions with pharmacological treatments.56

Pharmacological interventions

Given the altered risk–benefit ratio of pharmacological therapy in breastfeeding women, some guidelines state that antidepressants are only recommended if the woman expresses a preference for medication, declines psychological therapies, or if symptoms have not responded to other interventions.15 Specific evidence for the use of antidepressants for treating postnatal depression is limited because most randomised controlled trials of psychotropics exclude women who are pregnant or breastfeeding, and therefore guidelines tend to extrapolate findings from non-breastfeeding women. In terms of evidence for possible harms, while there have been a number of studies looking at the safety of antidepressants for perinatal women (e.g. Huybrechts et al..64), it remains unclear if there are specific impacts which are independent of the impact of depression.65 However, compared to fetal exposure during pregnancy, exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) through breast milk is very low.47

The majority of recent research has focused on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Pooled estimates for response and remission suggests that SSRIs are more effective than placebo for PND, but this is based on small samples and the quality of the evidence is rather low.59 The SSRI with the lowest rate of reported adverse effects on breastfed babies is sertraline.65 This is therefore most often recommended in guidelines (see below). For non-breastfeeding women, the choice of antidepressant will be the same as that for a major depressive episode at other times and will depend on the history of response to individual antidepressants.

Clinical guidance

Based on the available evidence for both psychosocial/psychological and pharmacological interventions, clinical guidance for the treatment of PND has been developed in several countries and is regularly updated.

In general, women who are at risk due to a history of severe depressive disorder before or during their pregnancy should have a detailed written care plan for the postnatal period, which has been agreed with the woman and has been shared with other professionals involved in her care.66 Women who are identified as having symptoms of PND should be given a full psychosocial assessment, ideally by their primary care practitioner or a mental health professional, which includes asking about family history, history of mental health disorders, current circumstances and interpersonal relationships. They should be seen for treatment quickly, as persistent symptoms are those most likely to lead to adverse outcomes.

Mild to moderate depression

- UK guidelines15 recommend facilitated self-help based on CBT principles for mild–moderate depression. This is the provision of written materials that include information about depression and interventions such as behavioural activation and problem-solving techniques. The materials are supported by a trained practitioner across 6–8 sessions which can take place face-to-face or via telephone. For women with a history of severe depression who present with mild depression in the postnatal period the guidelines recommend a tricyclic antidepressant (TCA), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or (serotonin-)noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor ((S)NRI). These two interventions can be used in combination if there is a limited response to either treatment alone.

- Australian guidelines47 recommend structured psychoeducation, advice around increasing social support, and structured psychological interventions such as CBT or IPT, which are all classed as evidence-based interventions. They also recommend guided self-help based on CBT principles, although the evidence base for this treatment is currently lacking.

- American Psychiatric Association guidelines do not specify treatments by severity but suggest that psychotherapies such as IPT and CBT should be considered as a first-line treatment or in combination with medication for pregnant and postnatal women.67

- The World Health Organization’s (WHO) mhGAP Intervention Guide also does not differentiate by severity.49 It recommends providing psychoeducation, strengthening social support, promoting functioning in daily activities and, if available, referring to brief psychological treatment such as IPT, CBT or counselling. It suggests avoiding antidepressants if possible or using the lowest effective dose if there is no response to psychological treatment.

- WHO has also developed ‘Thinking Healthy: A manual for psychosocial management of perinatal depression’ as part of its Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP).68 The Thinking Healthy manual is specifically intended to provide instructions to non-specialist health care workers about how to deliver evidence-based treatments for perinatal depression (see ‘Useful Links’ below).

Moderate to severe depression

- UK guidance recommends a high-intensity psychological intervention such as CBT. This is an individual face-to-face intervention delivered by a qualified therapist. The guidance also recommends a TCA, SSRI or (S)NRI if the woman understands the risks associated with the medication and she has expressed a preference for this or her symptoms have not responded to psychological interventions.

- Australian guidance recommends SSRIs as first-line treatment, with advice around the addition of psychological interventions as a useful adjunct once medications have become effective.

Overall, women should be involved in discussions about their care and be provided with appropriate information about risks and benefits to help them make decisions about treatment. Where pharmacological treatments are being considered for breastfeeding women, a risk–benefit analysis should be performed, taking into account the risks for the mother as well as the risks to the infant and the risks to both of non-treatment (see Box 3). Suitable treatment options should be used as opposed to recommending avoidance of breastfeeding. If an antidepressant has been used during pregnancy, it will usually be appropriate to continue with this treatment to minimize withdrawal symptoms in the infant. Guidance recommends using the lowest effective dose for the shortest period necessary.66

Practitioners are advised to consult local protocols and relevant professional guidance when considering medications and dosage. An example of the guidance provided for UK prescribers can be found here: https://www.bnf.org/

Box 3 Considerations when deciding on treatment options for PND (adapted from Australian practice guidelines)

- The likely benefits of each treatment, taking into account the severity of depressive symptoms.

- The risks and harms to the woman and baby associated with different treatments.

- The woman’s response to any previous treatment.

- The background risk of harm to the woman and baby associated with no treatment.

- The need for prompt initiation of treatment and monitoring of response due to the effect of non-treatment on the woman’s ability to fulfil the parenting role.

- The risk of harm associated with stopping or changing treatment.

- The side effects of any medication taken by the woman.

(For up to date information about using medicines in pregnancy please refer to: http://www.uktis.org/)

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- Enquiry about mental health symptoms should take place at all postnatal consultations. Where core symptoms of depression such as low mood and loss of interest are present, a full psychosocial assessment should be undertaken.

- Health professionals should allow adequate time to assess, listen and build rapport with women in the perinatal period, maintaining a non-judgemental stance and addressing any worries about stigma.

- Women should be involved in all decisions about their care and given adequate, culturally appropriate information to support their decisions.

- Women who are at risk due to a history of severe depressive disorder before or during their pregnancy or who are identified as having symptoms of PND should have a detailed written care plan for the postnatal period, which has been agreed with the woman and has been shared with other professionals involved in her care.

- For mild to moderate symptoms, psychological therapies are a first-line treatment, alongside strengthening social support.

- For moderate to severe symptoms, medication and psychological therapies are recommended.

- When making treatment decisions, the potential benefits and harms of different treatments, as well as the consequences of no treatment, should be considered, alongside the woman’s preferences.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) of this chapter declare that they have no interests that conflict with the contents of the chapter.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

USEFUL LINKS

Medication and prescribing

The UK teratology information service: http://www.uktis.org/

The British Medical Association’s British National Formulary: https://www.bnf.org/

Psychosocial Intervention

The WHO mhGAP Intervention Guide: http://www.who.int/mental_health/publications/mhGAP_intervention_guide/en/

The WHO Thinking Healthy manual: http://www.who.int/mental_health/maternal-child/thinking_healthy/en/

Online training resources for health professionals

https://bettercare.co.za/learn/maternal-mental-health/text/0–3-contents.html

REFERENCES

Fisher J, Mello, M.Cd., Patel V, Rahman A, Tran T, Holton S, et al. Prevalence and determinants of common perinatal mental disorders in women in low-and lower-middle-income countries: a systematic review. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2012;90:139–49. | |

Gavin NI, Gaynes BN, Lohr KN, Meltzer-Brody S, Gartlehner G, Swinson T. Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2005;106(5):1071–83. | |

O'Hara MW, McCabe JE. Postpartum depression: current status and future directions. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 2013;9:379–407. | |

Howard LM, Molyneaux E, Dennis, C.-L., Rochat T, Stein A, Milgrom J. Non-psychotic mental disorders in the perinatal period. The Lancet 2014;384(9956):1775–88. | |

Cameron EE, Sedov ID, Tomfohr-Madsen LM. Prevalence of paternal depression in pregnancy and the postpartum: an updated meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders 2016;206:189–203. | |

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edn. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2013. | |

World Health Organization. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1992. | |

Bilszta J, Ericksen J, Buist A, Milgrom J. Women's experience of postnatal depression-beliefs and attitudes as barriers to care. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing, The 2010;27(3):44. | |

Mauthner NS. "Feeling low and feeling really bad about feeling low": Women's experiences of motherhood and postpartum depression. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne 1999;40(2):143. | |

Sundström Poromaa I, Comasco E, Georgakis MK, Skalkidou A. Sex differences in depression during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Journal of Neuroscience Research 2017;95(1–2):719–30. | |

Bennett HA, Einarson A, Taddio A, Koren G, Einarson TR. Prevalence of depression during pregnancy: systematic review. Obstet Gynecol 2004;103(4):698-709. | |

Norhayati M, Hazlina NN, Asrenee A, Emilin WW. Magnitude and risk factors for postpartum symptoms: a literature review. Journal of Affective Disorders 2015;175:34–52. | |

Paulson JF, Bazemore SD. Prenatal and postpartum depression in fathers and its association with maternal depression: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2010;303(19):1961–9. | |

Darwin Z, McGowan L, Edozien LC. Identification of women at risk of depression in pregnancy: using women’s accounts to understand the poor specificity of the Whooley and Arroll case finding questions in clinical practice. Archives of Women's Mental Health 2016;19(1):41–9. | |

NICE. Antenatal and postnatal mental health: clinical management and service guidance. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2014. | |

Coelho HF, Murray L, Royal-Lawson M, Cooper PJ. Antenatal anxiety disorder as a predictor of postnatal depression: a longitudinal study. Journal of Affective Disorders 2011;129(1–3):348–53. | |

Stewart DE, Vigod S. Postpartum depression. New England Journal of Medicine 2016;375(22):2177–86. | |

Dias CC, Figueiredo B. Breastfeeding and depression: a systematic review of the literature. Journal of Affective Disorders 2015;171:142–54. | |

Khalifa DS, Glavin K, Bjertness E, Lien L. Determinants of postnatal depression in Sudanese women at 3 months postpartum: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2016;6(3):e009443. | |

Alder E, Bancroft J. The relationship between breast feeding persistence, sexuality and mood in postpartum women. Psychological Medicine 1988;18(2):389–96. | |

Muscat T, Obst P, Cockshaw W, Thorpe K. Beliefs about infant regulation, early infant behaviors and maternal postnatal depressive symptoms. Birth 2014;41(2):206–13. | |

Sharkey KM, Iko IN, Machan JT, Thompson-Westra J, Pearlstein TB. Infant sleep and feeding patterns are associated with maternal sleep, stress, and depressed mood in women with a history of major depressive disorder (MDD). Archives of Women's Mental Health 2016;19(2):209–18. | |

Kim P, Swain JE. Sad dads: paternal postpartum depression. Psychiatry (edgmont) 2007;4(2):35. | |

Glasser S, Lerner-Geva L. Focus on fathers: paternal depression in the perinatal period. Perspectives in public health. 2018:1757913918790597. | |

Knight M, Nair M, Tuffnell D, Shakespeare J, Kenyon S, Kurinczuk J (eds.) on behalf of MBRRACE-UK. Saving Lives, Improving Mothers’ Care – Lessons learned to inform maternity care from the UK and Ireland Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity 2013–15. Oxford: National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford, 2017. | |

Lawrence E, Rothman AD, Cobb RJ, Rothman MT, Bradbury TN. Marital satisfaction across the transition to parenthood. Journal of Family Psychology 2008;22(1):41. | |

Murray L, Arteche A, Fearon P, Halligan S, Goodyer I, Cooper P. Maternal postnatal depression and the development of depression in offspring up to 16 years of age. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2011;50(5):460–70. | |

Glover V, Capron L. Prenatal parenting. Current Opinion in Psychology 2017;15:66–70. | |

Letourneau NL, Dennis CL, Cosic N, Linder J. The effect of perinatal depression treatment for mothers on parenting and child development: A systematic review. Depression and Anxiety 2017;34(10):928–66. | |

Murray L, Fearon P, Cooper P. Postnatal depression, mother-infant interactions, and child development. Identifying perinatal depression and anxiety: Evidenced-based practice in screening, psychosocial assessment, and management, 2015:139–64. | |

Field T. Postpartum depression effects on early interactions, parenting, and safety practices: a review. Infant Behavior and Development 2010;33(1):1–6. | |

NICHD ECCRN. Chronicity of maternal depressive symptoms, maternal sensitivity, and child outcomes at 36 months. Developmental Psychology 1999;35(5):1297–310. | |

Netsi E, Pearson RM, Murray L, Cooper P, Craske MG, Stein A. Association of persistent and severe postnatal depression with child outcomes. JAMA Psychiatry 2018;75(3):247–53. | |

Malmberg LE, Lewis S, West A, Murray E, Sylva K, Stein A. The influence of mothers' and fathers' sensitivity in the first year of life on children's cognitive outcomes at 18 and 36 months. Child: Care, Health and Development 2016;42(1):1–7. | |

Sweeney S, MacBeth A. The effects of paternal depression on child and adolescent outcomes: a systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders 2016;205:44–59. | |

Hanington L, Heron J, Stein A, Ramchandani P. Parental depression and child outcomes–is marital conflict the missing link? Child: Care, Health and Development 2012;38(4):520–9. | |

Milgrom J, Gemmill AW. Introduction: Current Issues in Identifying Perinatal Depression: An Overview. Identifying Perinatal Depression and Anxiety: Evidence? Based Practice in Screening, Psychosocial Assessment, and Management, 2015:1–10. | |

Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression: development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. The British Journal of Psychiatry 1987;150(6):782–6. | |

Matthey S. Are we overpathologising motherhood? Journal of Affective Disorders 2010;120(1–3):263–6. | |

Milgrom J, Mendelsohn J, Gemmill AW. Does postnatal depression screening work? Throwing out the bathwater, keeping the baby. Journal of Affective Disorders 2011;132(3):301–10. | |

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine 2001;16(9):606–13. | |

Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck depression inventory-II. San Antonio, 1996;78(2):490–8. | |

Goldberg DP. The detection of psychiatric illness by questionnaire: A technique for the identification and assessment of non-psychotic psychiatric illness. London: Oxford University Press, 1972. | |

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Medical Care 2003:1284–92. | |

Whooley MA, Avins AL, Miranda J, Browner WS. Case-finding instruments for depression. Journal of General Internal Medicine 1997;12(7):439–45. | |

Howard LM, Ryan EG, Trevillion K, Anderson F, Bick D, Bye A, et al. Accuracy of the Whooley questions and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in identifying depression and other mental disorders in early pregnancy. 2018;212(1):50-6 | |

Austin, M.-P., Highet N, Expert Working Group. Mental health care in the perinatal period: Australian clinical practice guideline. Melbourne: Centre of Perinatal Excellence, 2017. | |

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Screening for Perinatal Depression. Committe Opinion No. 630. Obstet Gynecol 2015;125:1268–71. | |

World Health Organization. mhGAP Intervention Guide – Version 2.0 for mental, neurological and substance use disorders in non-specialized health settings. World Health Organization, 2016. | |

Falah-Hassani K, Shiri R, Dennis, C.-L. The prevalence of antenatal and postnatal co-morbid anxiety and depression: a meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine 2017;47(12):2041–53. | |

Heron J, McGuinness M, Blackmore ER, Craddock N, Jones I. Early postpartum symptoms in puerperal psychosis. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 2008;115(3):348–53. | |

Morrell CJ, Sutcliffe P, Booth A, Stevens J, Scope A, Stevenson M, et al. A systematic review, evidence synthesis and meta-analysis of quantitative and qualitative studies evaluating the clinical effectiveness, the cost-effectiveness, safety and acceptability of interventions to prevent postnatal depression. Health Technology Assessment 2016;20(37). | |

MacArthur C, Winter H, Bick D, Lilford R, Lancashire R, Knowles H, et al. Redesigning postnatal care: a randomised controlled trial of protocol-based midwifery-led care focused on individual women's physical and psychological health needs. NCCHTA, 2003. | |

Buist A, Westley D, Hill C. Antenatal prevention of postnatal depression. Archives of Women's Mental Health 1999;1(4):167–73. | |

Petrou S, Cooper P, Murray L, Davidson LL. Cost-effectiveness of a preventive counseling and support package for postnatal depression. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care 2006;22(4):443–53. | |

Sockol LE, Epperson CN, Barber JP. A meta-analysis of treatments for perinatal depression. Clinical Psychology Review 2011;31(5):839–49. | |

Cluxton-Keller F, Bruce ML. Clinical effectiveness of family therapeutic interventions in the prevention and treatment of perinatal depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One 2018;13(6):e0198730. | |

Scope A, Booth A, Morrell CJ, Sutcliffe P, Cantrell A. Perceptions and experiences of interventions to prevent postnatal depression. A systematic review and qualitative evidence synthesis. Journal of Affective Disorders 2017;210:100–10. | |

Molyneaux E, Howard LM, McGeown HR, Karia AM, Trevillion K. Antidepressant treatment for postnatal depression. The Cochrane Library 2014. | |

Turner KM, Sharp D, Folkes L, Chew-Graham C. Women's views and experiences of antidepressants as a treatment for postnatal depression: a qualitative study. Family Practice 2008;25(6):450–5. | |

Dennis CL, Hodnett E. Psychosocial and psychological interventions for treating postpartum depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;4(4). | |

Cuijpers P, Brännmark JG, van Straten A. Psychological treatment of postpartum depression: a meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology 2008;64(1):103–18. | |

Lau Y, Htun TP, Wong SN, Tam WSW, Klainin-Yobas P. Therapist-supported internet-based cognitive behavior therapy for stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms among postpartum women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2017;19(4). | |

Huybrechts KF, Bateman BT, Palmsten K, Desai RJ, Patorno E, Gopalakrishnan C, et al. Antidepressant use late in pregnancy and risk of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. JAMA 2015;313(21):2142–51. | |

McAllister-Williams RH, Baldwin DS, Cantwell R, Easter A, Gilvarry E, Glover V, et al. British Association for Psychopharmacology consensus guidance on the use of psychotropic medication preconception, in pregnancy and postpartum 2017. Journal of Psychopharmacology 2017;31(5):519–52. | |

SIGN. SIGN 127: Management of perinatal mood disorders. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 2012. | |

American Psychiatric Association. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder, 3rd edn. American Psychiatric Association, 2010. | |

World Health Organization. Thinking healthy: a manual for psychosocial management of perinatal depression, WHO generic field-trial version 1.0, 2015. 2015. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards programme CLICK HERE)