This chapter should be cited as follows:

Hogg JL, Elhodaiby MK, et al., Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.416523

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Obstetrics Module

Volume 15

The puerperium

Volume Editors:

Dr Kate Lightly, University of Liverpool, UK

Professor Andrew Weeks, University of Liverpool, UK

Chapter

Perineal Care and Postpartum Urogynecology

First published: March 2024

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

INTRODUCTION

Perineal injury is the most common maternal morbidity associated with vaginal birth. Globally the incidence varies between 70% and 85% following vaginal birth.1,2 Injury to the perineum during childbirth can occur spontaneously or be induced by a surgical incision (episiotomy). Perineal tears can be classified into four different degrees, depending on the severity, as outlined earlier in this volume3 (Table 1).

Roughly 60% of women with tears will require surgical repair. Episiotomies can be performed to facilitate childbirth and affect the skin and muscle of the perineum, so it is compared to the second-degree perineal tear. Episiotomy and spontaneous tear can occur together, for example, an episiotomy may extend into a third-degree tear. They invariably require surgical repair.

1

Grades of perineal tears.

Grade of tear | Description of tear |

First degree | Injury to perineal skin and/or vaginal mucosa |

Second degree | Injury to perineum involving perineal muscles but not involving the anal sphincter |

Third degree | Injury to perineum involving sphincter complex |

Fourth degree | Injury to perineum involving anal sphincter complex and rectal mucosa |

If perineal injury is not managed correctly, it can lead to hematoma formation, infection, urinary incontinence, fecal incontinence, painful sexual intercourse, and persistent perineal pain. These morbidities have a major impact on women’s quality of life, and the focus should be on trying to prevent these injuries from occurring.4 The literature shows there are several predictors of perineal trauma such as, maternal age, parity, gestational age, induction of labor, mode of delivery, position of delivery and birth weight.2 These risk factors must be considered in every woman as she prepares for childbirth.

In those in whom an injury occurs, a careful assessment should be made, and supportive care put in place. This is essential when preventing the long-term consequences of injury to the perineum and the pelvic floor, such as urinary and fecal incontinence.5,6

PERINEAL INJURY

Reducing the risk of perineal injury

Whilst it is important to effectively identify and treat perineal trauma, there are a variety of ways to reduce the risk of perineal injury both antenatally and during delivery.

Antenatal Risk Reduction

In the antenatal period, evidence has shown that perineal massage from 35 weeks of pregnancy until the time of delivery, can reduce the risk of perineal tears and the need for episiotomy in primiparous women.7,8 Perineal massage involves gentle stretching of the skin at the posterior fourchette with clean fingers and a lubricant such as olive oil or almond oil (Figure 1).

1

Perineal Massage Technique. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Reducing Your Risk of Perineal Tears. Available from: https://www.rcog.org.uk/en/patients/tears/reducing-risk/ [Accessed 23rd January 2021].

Hyperlink: https://www.rcog.org.uk/en/patients/tears/reducing-risk/

Hyperlink: https://www.rcog.org.uk/en/patients/tears/

Delivery Risk Reduction

During delivery, a warm compress applied continuously to the perineum during the second stage may reduce the incidence of third and fourth degree tears and therefore should be offered to women if available.9,10

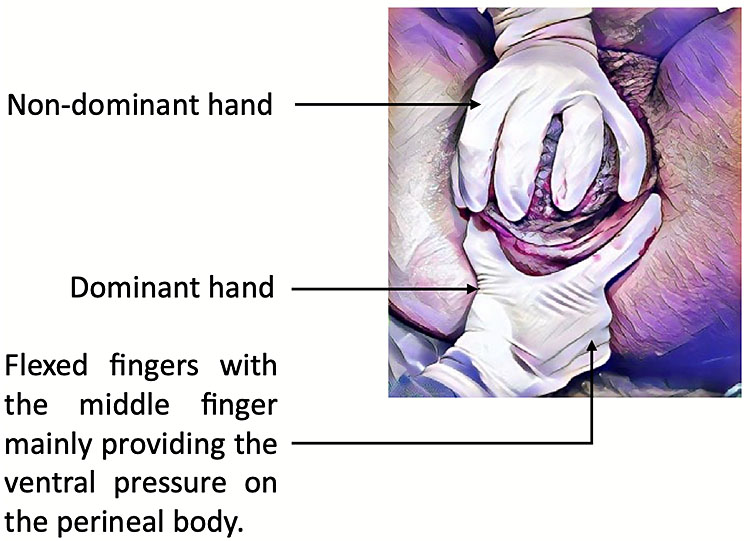

Manual protection of the perineum during crowning, (using the Finnish Grip) (Figure 2), should be performed in all positions except water births, breech births or births in a very upright position for example on a birthing stool.11 Healthcare practitioners should use one hand to provide perineal protection, with the other hand controlling the delivery of the fetal head.

2

Finnish Grip. Kleprlikova H, Kalis V, Lucovnik M, et al. Manual Perineal Protection: The know-how and the know-why. ACTA Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavic 2019;99(4):445–50. Available from https://obgyn-onlinelibrary-wiley-com.bris.idm.oclc.org/doi/pdfdirect/10.1111/aogs.13781 [Accessed 23rd January 2021].

Hyperlink: https://www.rcog.org.uk/en/guidelines-research-services/audit-quality-improvement/oasi-care-bundle/

Hyperlink: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/pregnancy-and-baby/episiotomy/

Appropriate Use of Episiotomy:

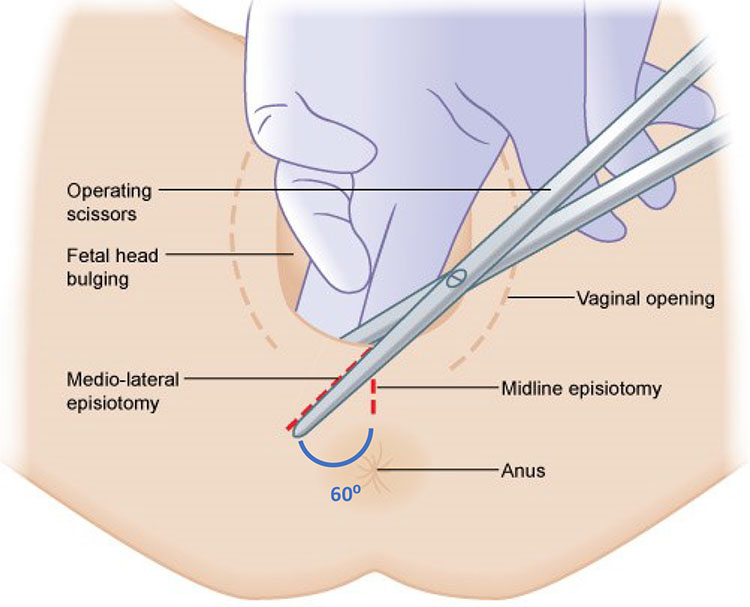

A medio-lateral episiotomy should be performed when indicated, during crowning, at an angle of 60 degrees from the midline4,12,13 (Figure 3). Instruments such as the Epi-scissors, if available, can help to improve episiotomy technique.14 Indications for an episiotomy include:

- Fetal distress – to expedite delivery

- Imminent severe perineal tear

- All term forceps deliveries

- All term ventouse/Kiwi deliveries in primiparous women

- Breech vaginal delivery

3

Mediolateral Episiotomy. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Assessing Need for Episiotomy. Available from: https://elearning.rcog.org.uk//easi-resource/vacuum-extraction/delivery/assessing-need-episiotomy [Accessed 23rd January 2021].

Perineal Repair

The details of surgical repair of episiotomies is covered in the chapter on trauma (see Management of the Obstetric Patient with Trauma by Alice Beardmore-Gray).

Perineal hygiene

Perineal hygiene is essential to protect the integrity of the skin, reduce the risk of infection and promote healing. Women should be advised to wash their hands before and after going to the toilet or when changing sanitary wear. Women using sanitary wear should be advised to change this at regular intervals. The perineal area should be cleaned daily using only water (no creams, oils, or herbs), then patted gently to dry or allowed to dry naturally.

A balanced diet and good hydration with at least two liters of fluid a day, will help to reduce constipation and straining. Using physiological positions, such as a small footstool to elevate the knees, could facilitate opening of the bowels.9 Women should be encouraged to wipe their bottom gently in a front to back direction to reduce the spread of bacteria from the anus.15

Perineal pain

Pain and discomfort particularly in the first 2 to 3 weeks is common following perineal trauma. Simple analgesia, such as paracetamol and ibuprofen, are effective and safe for breastfeeding mothers. Ice packs wrapped in a towel and applied to the perineum, can also help reduce swelling and discomfort.9

Many women will experience stinging or burning around a tear when urinating. Pouring warm water over the area when urinating or urinating in the bath or shower can help to reduce this. Women experiencing persistent dysuria should seek the advice of a healthcare professional to exclude urinary tract infection. If women are experiencing increasing pain or discomfort, they should be reviewed by their healthcare professional and an examination of the perineum should be performed. This should involve inspection of the tear/sutures, a swab of the area plus oral antibiotics if infection is suspected, and both a vaginal and rectal examination to assess for puerperal genital hematoma.

If perineal pain persists for more than six months, and no identifiable cause is detected, then it would be appropriate to refer the woman to a pain medicine specialist, if available. Alternatively, analgesia, perineal massage, pelvic floor exercises, and vaginal dilators can all be useful in treating persistent vaginal or vulval pain.

Hyperlink: https://uroweb.org/guideline/chronic-pelvic-pain/

Puerperal genital hematomas

Presentation:

Large hematomas generally present within the first few hours of delivery. Patients report rapidly increasing perineal, rectal, or abdominal pain, disproportionate to the degree of perineal trauma, which does not improve with analgesia. Some patients will show signs of hypovolemia, display increased lochia, or even present with collapse.

87% of puerperal genital hematomas (PGHs), are associated with direct injury to a blood vessel.15 For example, a tear/episiotomy, or injury from a needle during pudendal block or perineal infiltration. The remainder result from indirect injury during passage of the fetal head in the second stage.

Risk factors for PGHs include the following:15

- Primiparity.

- Prolonged second stage of labor.

- Instrumental delivery.

- Birthweight over 4 kg.

- Genital varicosities.

Some hematomas are visible on inspection, but many are concealed. The location of the hematoma depends on the vessel injured:

- Vulval/vulvovaginal – these haematomas arise superficial to the anterior urogenital diaphragm, resulting from damage to branches of the pudendal artery.15

- Vaginal – these are confined to the paravaginal tissues often extending into the ischiorectal space, resulting from damage to the descending branch of the uterine artery.15

- Supravaginal/sub peritoneal – these are within the broad ligament or extending retroperitoneally, resulting from damage to the branches of the uterine artery in the broad ligament.15

Assessment:

If PGH is suspected, prompt assessment should be undertaken. This should include basic observations, abdominal examination, external inspection, and palpation of the perineum, vaginal, and rectal examination. Hematomas are firm and exquisitely tender to palpate. If a large hematoma is suspected or the patient is showing signs of hemodynamic compromise, it is advisable to gain large bore intravenous access, start fluid resuscitation, give tranexamic acid if available, check full blood count and clotting, and crossmatch blood for transfusion, if available.

Management:

Large (>5 cm) or rapidly expanding hematomas require prompt treatment to reduce further blood loss and control pain. Examination under anesthetic is needed (with broad-spectrum intra-venous antibiotic cover), to evacuate the clot and gain hemostasis of any visible bleeding points. Either primary repair with re-suturing of the wound and insertion of a pack or packing with secondary repair are both accepted techniques.15

Small static hematomas (<5 cm) can present insidiously, with gradually increasing pain in the days following delivery. These are generally best treated conservatively with a course of broad-spectrum oral antibiotics and simple analgesia.15

BLADDER CARE

During pregnancy, the bladder undergoes several physiological and anatomical changes that can affect its function. Higher estrogen levels lead to detrusor hypertrophy, whilst the increased levels of progesterone reduce bladder tone thereby increasing bladder capacity. Increased fluid intake occurs throughout all three trimesters with increased fluid output in the first two. Anatomically, the bladder is drawn upwards as the uterus increases in size, the bladder neck displaces forwards, the urethra lengthens, and pressure on the bladder and pelvic floor increases.16,17 Awareness of these changes and appropriate bladder care in the intrapartum and postpartum period are essential to protect the lower urinary tract and reduce the incidence of long-term complications.

Intrapartum bladder care

As the fetal head descends through the pelvis during delivery, pressure on the bladder neck and urethra increases, which can cause difficulty voiding with hesitancy and/or obstruction. A distended bladder can also obstruct descent of the fetal head. It is therefore important for healthcare professionals to develop a consistent bladder care protocol to follow during delivery to optimize progress in labor and reduce the incidence of urinary retention and bladder distension.

There is a lack of consensus and evidence to help guide bladder care in labor.18 However, during a vaginal delivery, many maternity units in the UK advise women to void at least every 4 h, with the timing, frequency, and volume of each void being recorded on the partogram. If a woman is unable to void, reports incomplete voiding, or has a palpable bladder, she should be offered clean intermittent catheterization (CIC) to ensure bladder emptying.

Epidural or opioid analgesia can reduce bladder senzation, cause drowsiness, and reduce mobility.19 In these circumstances, women should be given assistance to void in the toilet/on a bed pan or offered CIC. Most evidence suggests that there is no benefit in indwelling catheterization over CIC for women with an epidural in labor.20

In the event of an instrumental delivery (whether in the delivery room or in theater, with or without regional analgesia), the bladder should be emptied prior to delivery with CIC or if an indwelling catheter is in situ this should be removed. If an epidural top-up or spinal anesthetic has been performed, an indwelling catheter should be inserted at the end of the procedure to reduce the risk of retention and bladder distension in the immediate post-operative period where mobility and bladder senzation are reduced due to anesthesia and post-operative pain.

During a cesarean section, an indwelling catheter should be inserted once regional anesthesia is effective, or before general anesthetic is commenced. Catheterization ensures the bladder is empty during cesarean, thereby improving visibility of the lower segment and reducing the risk of bladder injury. It also lowers the risk of retention and bladder distension in the immediate post-operative period where mobility and bladder senzation are reduced due to anesthesia and post-operative pain.

Hyperlink: https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/gtg_26.pdf

Hyperlink: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/intrapartum-care-guidelines/en/

Post-partum bladder care

Following vaginal delivery or instrumental delivery without a spinal anesthetic or epidural top-up, women should be advised to void within 6 h and the timing and volume of this void should be measured and documented (please see NICE document below).

After a cesarean section, or instrumental delivery with spinal anesthetic or epidural top-up, the urinary catheter should not be removed for at least 12 h post-procedure, but the duration of catheterization should not routinely exceed 24 h. In some circumstances, such as in the event of a urethral tear or extensive vaginal trauma, an indwelling catheter may be inserted for around 24 h to reduce the risk of retention due to pain when voiding.

Healthcare professionals should ensure women have adequate analgesia and are able to safely mobilize before removing the catheter. Once the catheter has been removed, women should be advised to void within 6 h and the timing and volume of this void should be measured and documented. This can be done by asking women to pass urine into a simple graded container.

Hyperlink: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng194

Bladder complications

After childbirth, the bladder may not function properly for several reasons, including problems with voiding (usually secondary to hesitancy), urinary leakage, problems with incomplete evacuation, recurrent urinary infections, pain on micturition, and fistulas. In terms of physiology, women do not fully recover to their pre-pregnancy state until around 6 months post-partum, however, the genito-urinary system may take longer to recover, and in some cases may not fully revert to a pre-pregnancy level of function.21

Post-partum urinary retention

The commonest problem in the immediate post-partum period is post-partum urinary retention (PUR), which can occur following vaginal or cesarean delivery.22 Several studies have reported that PUR is usually self-limiting and many women have resolution of symptoms with no ongoing complications. However, in a small number of women, unrecognized and untreated PUR can lead to long-term voiding difficulties, recurrent urinary tract infections, and even impaired renal function.

Post-partum urinary retention (PUR) can be separated into two categories:23,24,25

- Overt (symptomatic) – the inability to void spontaneously within 6 h of delivery or removal of an indwelling catheter.

- Covert (asymptomatic) – women can void spontaneously but have a postvoid residual bladder volume of ≥150 mls.

Overt PUR has been reported as affecting between 0.3–4.7% of women, whereas covert PUR has been reported in up to 45% of post-partum women. The exact cause of PUR is unknown, but a variety of risk factors for PUR have been identified:23,24,25

- Primiparity.

- Episiotomy/perineal trauma.

- Epidural anesthesia.

- Larger birthweight.

- Instrumental delivery.

- Long labor, i.e., 1st stage >12 h and 2nd stage >2 h.

If women are unable to void after 6 h, have a void of <200 mls or feel unable to completely empty their bladder, conservative measures should be tried in the first instance. This includes helping women to mobilize to the toilet, encouraging double voiding, taking a warm bath or shower, ensuring adequate fluid intake and analgesia, and giving women privacy.

If conservative measures fail, bladder volume should be assessed using either a bladder scan (if available) or CIC.26 If the bladder volume is >150 mls this classifies as PUR.

There is a lack of evidence to guide further management of PUR once it has been diagnosed, therefore treatment varies widely, and may be dictated by the availability of equipment and experience in each unit.

Urinary incontinence

All types of urinary incontinence (UI) become more prevalent following pregnancy and childbirth. Prior to this, less than 1% of women report stress urinary incontinence (SUI) or urge urinary incontinence (UUI).21 The prevalence of SUI and UUI antenatally varies widely, ranging from 18.6–67% and 6.7–12.16%, respectively.27 In the post-partum period between 7% and 56% of women report SUI whilst UUI is reported in up to 30% of post-partum women.21,27

Post-partum UI is commonly associated with injury to the levator-ani muscle and the pudendal nerve, both of which are particularly vulnerable during vaginal delivery. Risk factors for post-partum UI include the following:28

- Maternal age >30.

- Multiparity.

- Raised BMI.

- Labor duration ≥8 h.

- Pelvic floor trauma, which is increased in the event of:

- Operative vaginal delivery.

- Episiotomy.

- Larger birthweight.

- Pre-existing UI/antenatal UI.

Whilst reported rates of both SUI and UUI are higher following vaginal delivery, it is important to note that cesarean delivery, particularly when performed in labor, does not necessarily prevent UI. Reported rates of UUI are around 9% after cesarean, whilst around 4–8% of women report symptoms of SUI following a planned cesarean and 12% following a cesarean in labor.29 More long term, some studies have shown similar rates of SUI in women who have had a cesarean birth, compared to women delivering vaginally.30

Most women will see improvement in UI symptoms in the first 6 months following delivery, as the connective tissues and pelvic floor muscles regain some of their pre-pregnancy function.21 Lower estrogen levels can exacerbate UI, so some women may find their symptoms improve once they have stopped breastfeeding.31

All women experiencing symptoms of UI should have a urine dipstick performed to investigate the possibility of a urinary tract infection (please see NICE Hyperlink below). Urinary tract infections should be treated with a course of antibiotics in accordance with local microbiology protocol. In the absence of a local protocol, WHO guidance recommends Amoxicillin, Amoxicillin + Clavulanic Acid, Nitrofurantoin, or Sulfamethoxazole + Trimethoprim as appropriate first-line antibiotics for urinary tract infection.32 Trimethoprim should be avoided in the first trimester of pregnancy due to the potential increased risk of neural tube defects, and Nitrofurantoin should be avoided in the third trimester due to an increased risk of neonatal jaundice.

Hyperlink: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng123

Women experiencing SUI should have supervised training in pelvic floor exercises, (PFE), ideally by a pelvic floor physiotherapist, for at least 3 months (please see NICE Hyperlink below). Post-partum PFE have been shown to be effective in decreasing urine leakage and improving reported symptoms. This is explored further in the section on physiotherapy below.

Hyperlink: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng123/chapter/recommendations

Women experiencing symptoms of UUI should be advised to reduce bladder irritants, such as caffeine, alcohol, citrus juices, and fizzy drinks and aim to drink around 2 liters of water a day. A bladder diary for a minimum of 3 days detailing fluid type, intake/output and symptoms can help to identify triggers. Bladder training for a minimum of 6 months can help to improve symptoms. The technique for bladder training can be found on the IUGA website (please see IGUA Hyperlink below). Women with a BMI ≥30 should be given advice and assistance to lose weight (please see NICE Hyperlink below).

Hyperlink: https://www.yourpelvicfloor.org/media/Bladder_Training_RV1-3.pdf

Hyperlink: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng123

Women experiencing ongoing urinary symptoms should be referred to specialist urogynaecologists for ongoing investigation and treatment. A mainstay of treatment of urinary incontinence is dedicated women’s health physiotherapy.

GENITAL TRACT FISTULAE

A fistula describes an abnormal passageway between one organ and another. Obstetric fistulae (OF) can occur following obstructed labor or as the result of perineal injury, particularly if this is not recognized and repaired appropriately. There are several different types of OF, and in cases of severe damage, more than one type of fistula can occur at the same time:33

- Vesicovaginal – between the bladder and the vagina.

- Urethrovaginal – between the urethra and the vagina.

- Rectovaginal – between the rectum and the vagina.

- Uterovesical – between the uterus and the bladder.

- Ureterovaginal – between the ureters and the vagina.

Whilst OF is a rare condition in high-income countries, in Sub-Saharan Africa and South East Asia it is estimated to affect at least 2 million women. Extrapolating from community-based studies, it is thought that between 30,000 and 130,000 new OF cases occur every year34 and that there could be up to a million women living with OF in Nigeria and over 70,000 in Bangladesh.35,36 At the very least, it is estimated that the incidence of OF is 1–10 per 1,000 births.35 The detailed management of OF is covered elsewhere in this textbook.

In the last few years, many changes have taken place to promote better care of women and girls with OF. These include the following:

- Increasing the number of competent fistula surgeons, using the FIGO/RCOG and Partners Competency-based manual for fistula surgery. In the last 5 years, over 50 trainers have been trained and over 40 new fistula surgeons have been signed off to standard level of training.

- Hyperlink: https://www.figo.org/what-we-do/obstetric-fistula

- Improving healthcare facilities in lower- and middle-income countries (LMICs) across Asia and Africa, which provide surgical and medical care for women with OF. These have mainly been driven by non-government organizations such as Engender Health, UNFPA, Direct Relief International and other agencies and foundations.

- Improving advocacy for OF patients through specialized reintegration programmes, like Terrewode’s social support program in Uganda.

- Hyperlink: https://terrewode.com/

Of all the issues that need to be addressed, perhaps the easiest would be prevention of obstetric trauma in the first place, by providing appropriate antenatal and intrapartum care; and using an evidence-based approach to surgical repair.

If a woman is identified at being at risk of OF, the insertion of an indwelling catheter during labor and the administration of antibiotics postpartum can help to prevent/reduce this risk. In the event of a vesicovaginal, urethrovaginal, or uterovesical fistula occurring, if this is identified in or shortly after labor, indwelling catheterization for 6–8 weeks can promote spontaneous closure.37,62

BOWEL CARE

Vaginal delivery represents the single most important aetiological factor for anal sphincter injury and the subsequent development of fecal incontinence in women.38 Two mechanisms of injury have been identified; direct anal sphincter muscle trauma, and indirect traction pudendal neuropathy, or a combination of these.38 Despite primary surgical repair, the functional outcome is often disappointing with studies reporting a varied prevalence of fecal incontinence (range 7–58%), mainly due to persisting sphincter defects.39 Prevention of anal sphincter injuries is therefore the key to reducing morbidity. However, although we are aware of the risk factors associated with anal sphincter trauma, the majority are not modifiable and only become apparent late in labor. It is therefore difficult to predict or control these risks to reduce the incidence of a third or fourth degree tear. In addition, many of the labor and delivery decisions are often dependant on complex inter-related risk factors.

Bowel care pre- and post-delivery is covered in the perineal trauma section. The mainstay of treatment of postpartum bowel problems is biofeedback therapy, which, where available, is part of dedicated women’s health physiotherapy.

SEXUAL PROBLEMS IN THE POSTPARTUM PERIOD

Trauma occurring at the time of childbirth may lead to chronic pelvic pain related to the site of injury. Female sexual dysfunction is perhaps the commonest presenting problem.40 There is often a transient problem with estrogen deficiency in the postpartum period and during breastfeeding. Denervation of the pelvic floor during delivery followed by re-innervation in the postpartum period, may also lead to dysfunction and pain.41

A mainstay of treatment of sexual pain/problems after childbirth is dedicated women’s health physiotherapy, which can include relaxation and contraction exercises modified for the women’s individual needs.

PHYSIOTHERAPY

It is well established that childbirth is associated with female pelvic floor dysfunction in the postpartum period.42,43,44 Physiotherapy is an important tool in reducing the risk and the impact, as well as managing pelvic floor dysfunction in the postpartum period. It is usually best taught by a dedicated women’s health physiotherapist.

Antenatal Physiotherapy

Pelvic floor exercises (PFE) can start during the antenatal period. Daily or more frequent PFE practice during pregnancy is associated with less reported postnatal incontinence.45 A 2017 Cochrane systematic review showed that compared with usual care, antenatal PFE were beneficial for both continent and incontinent pregnant women as it reduced reported urinary incontinence in late pregnancy and the mid-postnatal period. It is uncertain if antenatal PFE reduce urinary incontinence risk late postpartum.46 Studies are still evaluating the effect of an antenatal PFE program on female sexual function.47 In women with or without fecal incontinence, antenatal PFE led to little or no difference in the prevalence of fecal incontinence in late pregnancy.46

Postpartum Physiotherapy

When started after delivery, PFE is also effective in reducing the incidence and severity of urinary incontinence at 3 months after delivery.48 Evidence suggests that programs of PFE performed both in the immediate and late post-partum period result in a significant increase in muscle strength and reduced the risk of urinary incontinence,49 with objective improvement of existing urinary incontinence.50 However, the Cochrane systematic review showed that for PFE begun after delivery, there was considerable uncertainty about the effect on urinary incontinence risk in the late postnatal period.46 In postnatal women with persistent fecal incontinence, it was uncertain whether PFE reduced incontinence in the late postnatal period compared to usual care.46

Postpartum PFE also have a role in female sexual dysfunction and has been shown to improve sexual desire, arousal, orgasm, and satisfaction in the postpartum period, but is not associated with a decreased prevalence of perineal pain and dyspareunia.47,51

Obstetric anal sphincter injury, (OASI), involves deeper damage to the pelvic floor and the anal continence mechanism. PFE after OASI, has been shown to improve anal incontinence scores, (St. Mark’s Score), 6 months after primary repair of the injury.52 Early PFE (within 30 days of delivery), in women who have had an OASI, is thought to reduce leakage of wind, liquid stool leakage, and urinary stress incontinence.53 The long-term effects of peri-partum PFE beyond 1 year are unknown.54

The reported duration of postpartum PFE is variable, lasting for between 6–8 weeks to up to 6 months.48,50,52 There is a lot of variance in postnatal pelvic floor muscle training programs throughout the literature.55 Pelvic floor exercise programs are based on physiological evidence of the muscles that need to be trained to strengthen the pelvic floor.48 Exercises to minimize descent of the pelvic floor and pelvic organs are particularly important for postpartum women.48 Postpartum PFE regimes should also include advice and training about perineal splinting (supporting the perineum up to the anal sphincter with the hand during defaecation) and ‘the knack’ (perineal bracing during coughing, laughing, sneezing or lifting).48 Special devices and treatments, such as vaginal cones,56 electrical stimulation, and biofeedback can be used to improve technique.50

Hyperlink: https://www.nhs.uk/common-health-questions/womens-health/what-are-pelvic-floor-exercises/

Hyperlink: https://www.yourpelvicfloor.org/media/Pelvic_Floor_Exercises_RV2-1.pdf

Combination Therapy: Physiotherapy and Other Exercises

PFE can be combined with other strategies in a more holistic approach to improve quality of life in the postpartum period. For example, Sophrology childbirth-Kegel-Lamaze respiratory training (SLK triple therapy) improves maternal and fetal health by promoting postpartum pelvic floor function, reducing the incidence of depression, and enhancing sexual function.57 Combining PFE with a community-driven healthy nutrition and breastfeeding counseling program showed positive results.58 However, PFE was not found to be effective when the exercises were taught in a general fitness class for pregnant women, without individual instruction of correct pelvic floor muscle contraction.59 Digital online sources for PFE, are starting to show promise.60

Not all women are able perform PFE correctly. Some women would perform alternative actions when asked to do a pelvic floor contraction. COMMOV are "c"ontractions of "o"ther "m"uscles (m. rectus abdominus, the gluteal muscles, and the adductors), and other "mov"ements (pelvic tilt, breath holding, and straining) performed in addition to or instead of the PFE. COMMOV are probably the most common errors in attempt to contract the pelvic floor muscles during the first days after delivery and could be easily corrected by simple instructions.61

Thus, the role of physiotherapy in the postpartum period should be promoted not only for therapeutic purposes in the antenatal period and the immediate aftermath after delivery, but also as a ‘wellness’ and holistic approach for helping women with bladder, bowel, and sexual function care lifelong.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS TO REDUCE PERINEAL TRAUMA

For women in the second stage of labor:

- Use of perineal massage to help prevent vaginal/perineal trauma.

- Use of warm perineal compress compared with control to help reduce pain and trauma.

- Supportive delivery techniques in malpresentations to prevent soft tissue trauma in the pelvis.

- Physiotherapy and pelvic floor exercises.

For the community:

- Strong community support to develop solidarity groups which in under-resourced settings include village volunteers working with trained, skilled, and traditional birth attendants, depending on the local customs and resources.

- Components of the three delays need to be identified and targeted to minimize the effect of obstructed labor. This will benefit both mother and child. These include the following:

- Delays in seeing appropriate medical help for an obstetric emergency.

- Delay in reaching an appropriate obstetric facility.

- Receiving adequate care when the facility is reached.

- Provision of adequate health facilities/birthing centers, which provide emergency obstetric care, including operative vaginal delivery and cesarean section.

- Provision and use of nationally and internationally accepted guidelines for antenatal, intrapartum, and postpartum care.

Nationally:

- National policies for maternity care should be developed for all countries. In under-resourced settings they must be provided to also help prevent genital tract fistulas.

- Promotion of physiotherapy as a mainstay of treatment of postpartum pelvic floor dysfunction and prevention of long-term consequences of pelvic floor dysfunction.

- Data collection by local, national, and regional bodies should help to define the incidence of birth complications, and factors leading to the “Three Delays”.

- Education about normal and abnormal labor, and facilities, should be available for all pregnant women.

- Funding should be made available to retain adequately trained staff to provide safe care and support for women.

2

Learning outcomes to help demonstrate the knowledge, skills and attitudes required when clinically reviewing a postpartum patient requiring a urogynecology assessment..

Knowledge criteria | Clinical competency | Professional skills and attitudes | Training support | Evidence and knowledge assessment |

Diagnose and understand the causes of perineal trauma

| Know how to take a sympathetic history |

|

|

|

Know how to manage the following:

| Ability to lead perineal care with midwives Coordinate appropriate bowel preparation Ensure high standard for the surgical management of perineal trauma and anal sphincter injury.

| Understanding of role of other health care professionals in a multi-disciplinary team particularly nursing, physiotherapy, and psychologist/counselor Demonstration of empathy with patients | Learn holistic care of the patient from nurses, physiotherapists, and other members of the hospital team | |

Be aware of the good principles’ perineal injury Have good knowledge of technique associated with the surgical repair of perineal injury | Postoperative pain, fluid, bladder, and bowel management | Understanding of role of other health care professionals in a multi-disciplinary team particularly nursing, physiotherapy, and psychologist/counselor Demonstration of empathy with patients | Learn holistic care of the patient from nurses, physiotherapists, and other members of the hospital team |

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) of this chapter declare that they have no interests that conflict with the contents of the chapter.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

GUIDELINES AND POLICIES RELEVANT TO THIS CHAPTER:

- WHO Recommendations: Intrapartum care for a positive childbirth experience:

https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/intrapartum-care-guidelines/en/ - Cochrane Database or Systematic Reviews: Perineal techniques during the second stage of labor for reducing perineal trauma:

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD006672.pub3/full - RCOG Green-top Guideline No 26: Operative Vaginal Delivery:

https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/gtg_26.pdf - RCOG The OASI Care Bundle Project:

https://www.rcog.org.uk/en/guidelines-research-services/audit-quality-improvement/oasi-care-bundle/ - European Association of Urology Guidelines: Chronic Pelvic Pain:

https://uroweb.org/guideline/chronic-pelvic-pain/ - NICE Clinical Guideline 194: Postnatal Care:

Https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng194 - WHO Model List of Essential Medicines:

https://list.essentialmeds.org/ - NICE Clinical Guideline 123: Urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse in women: management:

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng123

REFERENCES

Abedzadeh-Kalahroudi M, Talebian A, Sadat Z, et al. Perineal trauma: incidence and its risk factors. J Obstet Gynaecol 2019;39(2):206–11. | |

Marschalek ML, Worda C, Kuessel L, et al. Risk and protective factors for obstetric anal sphincter injuries: A retrospective nationwide study. Birth 2018;45(4):409–15. | |

Thubert T, Cardaillac C, Fritel X, et al. [Definition, epidemiology and risk factors of obstetric anal sphincter injuries: CNGOF Perineal Prevention and Protection in Obstetrics Guidelines]. Gynecol Obstet Fertil Senol 2018;46(12):913–21. | |

Bidwell P, Thakar R, Sevdalis N, et al. A multi-centre quality improvement project to reduce the incidence of obstetric anal sphincter injury (OASI): study protocol. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018;18(1):331. | |

Folch M, Pares D, Castillo M, et al. [Practical issues in the management of third and fourth degree tears to minimise the incidence of faecal incontinence]. Cir Esp 2009;85(6):341–7. | |

Samarasekera DN, Bekhit MT, Wright Y, et al. Long-term anal continence and quality of life following postpartum anal sphincter injury. Colorectal Dis 2008;10(8):793–9. | |

Ugwu EO, Iferikigwe ES, Obi SN, et al. Effectiveness of antenatal perineal massage in reducing perineal trauma and post-partum morbidities: A randomized controlled trial. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2018;44(7):1252–8. | |

Beckmann MM, Stock OM. Antenatal perineal massage for reducing perineal trauma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013(4):CD005123. | |

Aasheim V NA, Reinar LM, Lukasse M. Perineal techniques during the second stage of labour for reducing perineal trauma. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2017;13:1465–858 | |

Magoga G, Saccone G, Al-Kouatly HB, et al. Warm perineal compresses during the second stage of labor for reducing perineal trauma: A meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2019;240:93–8. | |

Sveinsdottir E, Gottfredsdottir H, Vernhardsdottir AS, et al. Effects of an intervention program for reducing severe perineal trauma during the second stage of labor. Birth 2019;46(2):371–8. | |

Stecher AM, Yeung J, Crisp CC, et al. Awareness Regarding Perineal Protection, Obstetric Anal Sphincter Injury, and Episiotomy Among Obstetrics and Gynecology Residents; Effects of an Educational Workshop. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg 2018;24(3):241–6. | |

Aasheim V, Nilsen ABV, Reinar LM, et al. Perineal techniques during the second stage of labour for reducing perineal trauma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;6:CD006672. | |

Cole J, Lacey L, Bulchandani S. The use of Episcissors-60 to reduce the rate of Obstetric Anal Sphincter Injuries: A systematic review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2019;237:23–7. | |

Mawhinney S HR. Puerperal genital haematoma: a commonly missed diagnosis. The Obstetrician and Gynaecologist 2007;9:195–200. | |

Chaliha C, Khullar V, Stanton SL, et al. Urinary symptoms in pregnancy: are they useful for diagnosis? BJOG 2002;109(10):1181–3. | |

Chaliha C, Stanton SL. Urological problems in pregnancy. BJU Int 2002;89(5):469–76. | |

Zaki MM, Pandit M, Jackson S. National survey for intrapartum and postpartum bladder care: assessing the need for guidelines. BJOG 2004;111(8):874–6. | |

Halpern SH, Leighton BL, Ohlsson A, et al. Effect of epidural vs. parenteral opioid analgesia on the progress of labor: a meta-analysis. JAMA 1998;280(24):2105–10. | |

Evron S, Dimitrochenko V, Khazin V, et al. The effect of intermittent versus continuous bladder catheterization on labor duration and postpartum urinary retention and infection: a randomized trial. J Clin Anesth 2008;20(8):567–72. | |

Romano M, Cacciatore A, Giordano R, et al. Postpartum period: three distinct but continuous phases. J Prenat Med 2010;4(2):22–5. | |

Humburg J. [Postartum urinary retention – without clinical impact?]. Ther Umsch 2008;65(11):681–5. | |

Chai AH, Wong T, Mak HL, et al. Prevalence and associated risk factors of retention of urine after caesarean section. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2008;19(4):537–42. | |

Yip SK, Brieger G, Hin LY, et al. Urinary retention in the post-partum period. The relationship between obstetric factors and the post-partum post-void residual bladder volume. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1997;76(7):667–72. | |

Yip SK, Sahota DS, Chang AM. A probability model for ultrasound estimation of bladder volume in the diagnosis of female urinary retention. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2003;55(4):235–40. | |

NICE Clinical Guideline 123: Urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse in women: management. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng123 [Accessed on 16th April 2021]. | |

Yi-Hao Lin S-DC, Wu-Chiao Hsieh, Yao-Lung Chang, Ho-Yen Chueh, An-Shine Chao, Ching-Chung Liang Persistent stress urinary incontinence during pregnancy and one year after delivery; its prevalence, risk factors and impact on quality of life in Taiwanese women: An observational cohort study. Taiwan Journal Obstetrics and GYnaecology 2018;57:340–5. | |

Fritel X, Fauconnier A, Bader G, et al. Diagnosis and management of adult female stress urinary incontinence: guidelines for clinical practice from the French College of Gynaecologists and Obstetricians. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2010;151(1):14–9. | |

Chaliha C, Digesu A, Hutchings A, et al. Caesarean section is protective against stress urinary incontinence: an analysis of women with multiple deliveries. BJOG 2004;111(7):754–5. | |

Fritel X, Ringa V, Quiboeuf E, et al. Female urinary incontinence, from pregnancy to menopause: a review of epidemiological and pathophysiological findings. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2012;91(8):901–10. | |

Weber MA, Kleijn MH, Langendam M, et al. Local Oestrogen for Pelvic Floor Disorders: A Systematic Review. PLoS One 2015;10(9):e0136265. | |

The 2019 WHO AWaRe classification of antibiotics for evaluation and monitoring of use. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2019. | |

The International Continence Society. Obstetric Fistula in the Developing World: An Introduction. Available from: https://www.ics.org/committees/developingworld/publicawareness/obstetricfistulaanintroduction [Accessed 16th April 2021]. | |

Wall LL. Obstetric vesicovaginal fistula as an international public-health problem. Lancet 2006;368(9542):1201–9. | |

Wall LL. Dead mothers and injured wives: the social context of maternal morbidity and mortality among the Hausa of northern Nigeria. Stud Fam Plann 1998;29(4):341–59. | |

york UN. Proceedings of South Asia Conference for the prevention and treatment of obstetric fistula, 2004. | |

Hilton P. Vesico-vaginal fistulas in developing countries. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2003;82(3):285–95 | |

Donnelly V, Fynes M, Campbell D, et al. Obstetric events leading to anal sphincter damage. Obstet Gynecol 1998;92(6):955–61. | |

Poen AC, Felt-Bersma RJ, Strijers RL, et al. Third-degree obstetric perineal tear: long-term clinical and functional results after primary repair. Br J Surg 1998;85(10):1433–8. | |

Hay-Smith EJ. Therapeutic ultrasound for postpartum perineal pain and dyspareunia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000(2):CD000495. | |

Cappell J, Pukall CF. Clinical profile of persistent genito-pelvic postpartum pain. Midwifery 2017;50:125–32. | |

Chiarelli P. Incontinence during pregnancy: prevalence of opportunities for continence promotion [Master's thesis]. Newcastle University, Australia: Newcastle, 1996. | |

Hampel C, Wienhold D, Benken N, et al. Prevalence and natural history of female incontinence. Eur Urol 1997;32(Suppl 2):3–12. | |

Thom D. Variation in estimates of urinary incontinence prevalence in the community: effects of differences in definition, population characteristics, and study type. J Am Geriatr Soc 1998;46(4):473–80. | |

Whitford HM, Alder B, Jones M. A longitudinal follow up of women in their practice of perinatal pelvic floor exercises and stress urinary incontinence in North-East Scotland. Midwifery 2007;23(3):298–308. | |

Woodley SJ, Boyle R, Cody JD, et al. Pelvic floor muscle training for prevention and treatment of urinary and faecal incontinence in antenatal and postnatal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;12:CD007471. | |

Sobhgol SS, Priddis H, Smith CA, et al. The Effect of Pelvic Floor Muscle Exercise on Female Sexual Function During Pregnancy and Postpartum: A Systematic Review. Sex Med Rev 2019;7(1):13–28. | |

Chiarelli P, Cockburn J. Promoting urinary continence in women after delivery: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2002;324(7348):1241. | |

Saboia DM, Bezerra KC, Vasconcelos Neto JA, et al. The effectiveness of post-partum interventions to prevent urinary incontinence: a systematic review. Rev Bras Enferm 2018;71(suppl 3):1460–8. | |

Sun ZJ, Zhu L, Liang ML, et al. Comparison of outcomes between postpartum and non-postpartum women with stress urinary incontinence treated with conservative therapy: A prospective cohort study. Neurourol Urodyn 2018;37(4):1426–33. | |

Battut A, Nizard J. [Impact of pelvic floor muscle training on prevention of perineal pain and dyspareunia in postpartum]. Prog Urol 2016;26(4):237–44. | |

Johannessen HH, Wibe A, Stordahl A, et al. Do pelvic floor muscle exercises reduce postpartum anal incontinence? A randomised controlled trial. BJOG 2017;124(4):686–94. | |

Mathe M, Valancogne G, Atallah A, et al. Early pelvic floor muscle training after obstetrical anal sphincter injuries for the reduction of anal incontinence. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2016;199:201–6. | |

Moossdorff-Steinhauser HFA, Berghmans BCM, Spaanderman MEA, et al. Urinary incontinence during pregnancy: prevalence, experience of bother, beliefs, and help-seeking behavior. Int Urogynecol J 2020. | |

Dumoulin C. Postnatal pelvic floor muscle training for preventing and treating urinary incontinence: where do we stand? Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2006;18(5):538–43. | |

Oblasser C, Christie J, McCourt C. Vaginal cones or balls to improve pelvic floor muscle performance and urinary continence in women post partum: A quantitative systematic review. Midwifery 2015;31(11):1017–25. | |

Liu D, Hu WL. SLK Triple Therapy Improves Maternal and Fetal Status and Promotes Postpartum Pelvic Floor Function in Chinese Primiparous Women. Med Sci Monit 2019;25:8913–9. | |

Walton LM, Raigangar V, Abraham MS, et al. Effects of an 8-week pelvic core stability and nutrition community programme on maternal health outcomes. Physiother Res Int 2019;24(4):e1780. | |

Bo K, Haakstad LA. Is pelvic floor muscle training effective when taught in a general fitness class in pregnancy? A randomised controlled trial. Physiotherapy 2011;97(3):190–5. | |

Goode K. Evaluation of a digital health resource providing physiotherapy information for postnatal women in a tertiary public hospital in Australia. Mhealth 2018;4:42. | |

Neels H, De Wachter S, Wyndaele JJ, et al. Common errors made in attempt to contract the pelvic floor muscles in women early after delivery: A prospective observational study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2018;220:113–7. | |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards programme CLICK HERE)