This chapter should be cited as follows:

Kuan KKW, Leonardi M, Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.417653

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Gynecology Module

Volume 3

Endometriosis

Volume Editors:

Professsor Andrew Horne, University of Edinburgh, UK

Dr Lucy Whitaker, University of Edinburgh, UK

Chapter

Diagnosing Endometriosis

First published: September 2022

Study Assessment Option

By completing 4 multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development awards from FIGO plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM

See end of chapter for details

INTRODUCTION

Diagnosing endometriosis can be challenging for clinicians due to its complex nature. Endometriosis most commonly presents with pelvic pain but can also manifest itself in various ways such as dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and infertility.1 The three most common subtypes of endometriosis are superficial endometriosis (SE), deep endometriosis (DE), and ovarian endometriomas (OE).2 According to the 2021 international working group of American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists (AAGL), European Society of Gynaecological Endoscopy (ESGE), European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE), and World Endometriosis Society (WES), SE consists of endometrium-like tissue lesions involving the peritoneal surface lining the pelvis and pelvic organs.3 Meanwhile, DE is defined as endometrium-like tissue lesions in the abdomen, extending on or under the peritoneal surface, which are usually nodular, able to invade adjacent structures, and associated with fibrosis and disruption of normal anatomy. Historically, DE was defined as endometriosis infiltrating a peritoneal surface by more than 5 mm.4 DE often affects the posterior compartment such as the uterosacral ligaments (USL) and bowel.5 OE are filled with dark endometrial fluid (hence, known as "chocolate cysts") that can develop anywhere in the pelvis, but most commonly in the ovaries. Less common sites of endometriosis can exist, such as diaphragmatic, thoracic, and abdominal wall, which will be discussed here as well.

Apart from the wide range of symptoms, diagnostic barriers such as delayed referrals to gynecologists, patient uncertainty between “normal” versus “abnormal” menstrual cycles, and stigmatization related to menstrual problems all contribute to the average diagnostic delay of 6.7 years, which can negatively impact the patient’s quality of life and work productivity.6,7 Currently, laparoscopic visualization and histological confirmation remains as the standard for making a definitive diagnosis but may not always be available or attainable for all patients for a variety of reasons. Furthermore, surgery as a diagnostic tool imparts many disadvantages including surgical complications and cost.8 Advancements in non-invasive (i.e. non-surgical) diagnostic tools have been made, including imaging tests such as ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), yielding improvements in diagnostic performance of OE and DE reliably.9 Non-invasive tests for biomarkers are also being studied but a reliable marker has not yet been identified.10,11,12 Others argue for a clinical diagnosis based on signs and symptoms rather than visualization of endometriosis itself or identification of abnormal testing.13 While research and adoption of novel diagnostic methods into clinical practice is ongoing, there does not appear to be one right answer for everyone. As such, we may consider categorizing diagnostic methods for endometriosis into five main pillars: clinical diagnosis, radiological diagnosis, biomarkers, surgery, and histopathology (Figure 1). It is important to recognize and understand the value of all possible diagnostic modalities, which can help patients achieve a timelier diagnosis and earlier initiative management strategies.13

1

The five pillars of endometriosis diagnosis. Created with BioRender.com.

CLINICAL DIAGNOSIS

Clinical History

Making a clinical diagnosis starts with taking a comprehensive history. Listening to a patient’s symptoms may point in the correct diagnostic direction and ascertain unique forms of endometriosis (Table 1). As mentioned earlier, pelvic endometriosis is commonly associated with pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, and dyspareunia, but these symptoms are non-specific and can be caused by other gynecological/non-gynecological pathologies. Asking about other characteristics such as chronic, cyclical, progressive, or intermenstrual pelvic pain can increase the accuracy of diagnosing endometriosis in the clinical setting.13 Certain menstrual history characteristics can also increase the risk of developing endometriosis such as early menarche before the age of 12 and short menstrual cycles (<26 days).14 Although rare, symptoms like focal abdominal pain, chest pain, or catamenial pneumothorax can be caused by extra-pelvic endometriosis and further investigations may be required.15 Previous cesarean section/abdominal surgical scars with focal abdominal pain further increases the likelihood for abdominal wall endometriosis (AWE).16

1

Common signs/symptoms depending on location of endometriosis.

Location of Endometriosis | Signs/Symptoms |

Pelvic endometriosis |

|

Abdominal wall endometriosis |

|

Thoracic endometriosis |

|

Red flags |

|

Another possible sign of endometriosis is subfertility. Approximately 15–30% of women undergoing assisted reproductive techniques are diagnosed with "unexplained infertility" with normal results following the standard infertility evaluation leaving endometriosis possibly undiagnosed.17 If endometriosis is diagnosed beforehand and surgically removed, around 41.9% of women may be able to achieve spontaneous pregnancy.18 The current American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) committee's opinion for the diagnostic evaluation of infertile females recommends laparoscopic investigation for women with a clear indication for peritoneal disease or advanced stages of endometriosis.19 However, other non-invasive and readily available imaging techniques such as transvaginal ultrasound (TVS) can easily be incorporated into routine infertility (guidance for performing the scan can be found under the "Ultrasound" section).

Beyond developing an understanding of a patient’s “endometriosis symptoms”, one must grasp the broader experience of the patient including co-existing symptom profiles, which may indicate co-morbidities and central sensitization (Table 2). For example, if a patient with an altered bowel habit is diagnosed with bowel endometriosis and managed accordingly, their symptoms may prevail due to unrecognized conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome. When preparing for laparoscopy, awareness of other underlying causes can allow clinicians to request other relevant specialists who can assist during surgery to treat existing co-morbidities minimizing the number of procedures required for the patient. Recently, a study by Orr and colleagues found that a Central Sensitization Inventory questionnaire score ≥40 can be a useful tool to identify those with endometriosis complicated by central sensitization,20 implying that treatments focused exclusively on endometriosis may not be as effective. An accurate and comprehensive appreciation of the patient’s constellation of symptoms and various diagnoses is vital to the ideal and specific management strategies that are implemented.

2

Symptoms between central sensitization syndromes and endometriosis.

Central Sensitization Syndromes | Possible Overlapping Symptoms with Endometriosis |

Irritable bowel syndrome |

|

Fibromyalgia |

|

Myofascial pelvic pain |

|

Painful bladder syndrome |

|

Physical Examination

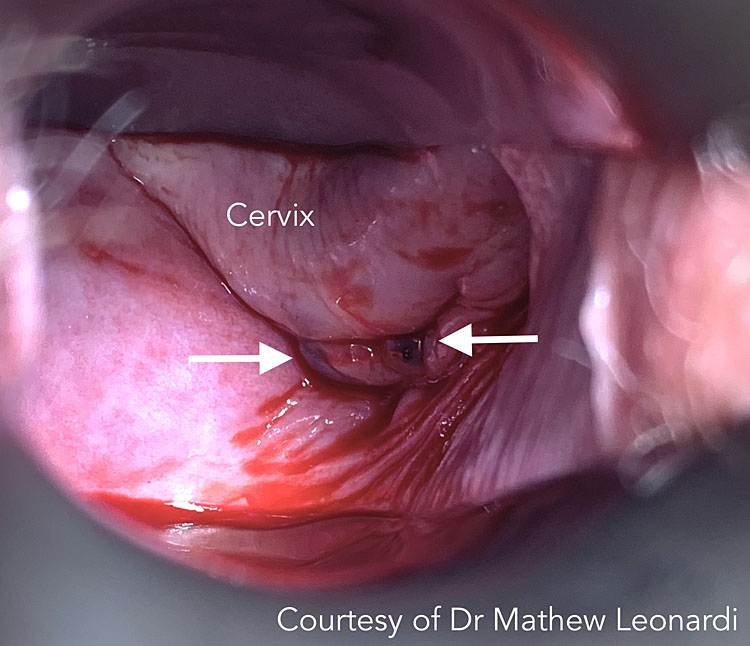

A physical examination for endometriosis includes general inspection of the external genitalia and bimanual pelvic examination. On speculum examination, red, blue, or hemorrhagic nodules may be seen on the external genitalia, vagina (Figure 2), and cervix.21 During a bimanual pelvic exam, the USL, vagina, rectovaginal space, pouch of Douglas (POD), rectosigmoid space, and posterior wall of the urinary bladder should be assessed for any adnexal masses, reduced cervical/uterine mobility, tenderness on palpation/movement, and nodularity in the posterior compartment structures.22 The 2022 ESHRE guideline for managing endometriosis also provides recommendations for localizing lesions based on findings.23 The presence of adnexal masses may suggest the presence of ovarian endometriomas. Furthermore, painful nodules in the rectovaginal wall or vaginal nodules in the posterior fornix may suggest DE.22 Some studies have suggested a link between endometriosis and a retroverted uterus, although the association is often non-significant.24,25 The specificity for localizing endometriosis using the bimanual technique is relatively high ranging from 86–99% while the sensitivity can range between 23–88% depending on the lesion location. The use of adjunct imaging techniques such as TVS can increase the sensitivity of localizing lesions to 67–99% allowing for a more accurate diagnosis and will be discussed in the next section.22 Physical examination for AWE should involve an abdominal examination where focal nodularity and tenderness may be appreciated. In rare circumstances (e.g. umbilical endometriosis) bleeding from an area of focus can be noted (Figure 3).

2

Vaginal endometriosis on speculum examination (white arrows). Courtesy of Dr Mathew Leonardi.

3

Umbilical endometriosis with bleeding (white arrows). Courtesy of Dr Mathew Leonardi.

RADIOLOGY

Regardless of whether the clinical examination is normal, imaging should be sought if endometriosis is suspected.23 Ultrasound and MRI are two common non-invasive techniques for diagnosing endometriosis with a high diagnostic accuracy (especially when used in combination) for detecting ovarian endometriomas, DE, and POD obliteration when performed systematically and with appropriate training.26 However, these imaging modalities are underappreciated and underutilized by gynecologists worldwide.27 In an international cross-sectional online survey, only 28.8% and 16.6% of the respondents believed that USS and MRI could diagnose endometriosis, respectively.27 When imaging is used pre-operatively, it can better prepare surgeons (e.g. requesting for a colorectal surgeon in the case of bowel DE) and avoid intra/post-operative surprises for both patients and clinicians.28 Computerized tomography (CT) and chest x-rays can also be used but is mainly indicated for thoracic endometriosis and excluding pulmonary diseases.29 Therefore, this section will mainly focus on ultrasound and MRI. Table 3 outlines the main imaging tests used for specific subtypes or locations of endometriosis.

3

Summary of radiological imaging techniques for endometriosis depending on disease location.

Location of Endometriosis | Imaging Techniques |

Pelvic endometriosis |

|

Appendix and ileocecal |

|

Abdominal wall endometriosis |

|

Thoracic endometriosis |

|

Abbreviations: IDEA, International Deep Endometriosis Analysis group; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; CT, computerized tomography; SE, superficial endometriosis.

ULTRASOUND

Ultrasound is an affordable, non-invasive, first-line imaging modality that can be performed quickly by an experienced clinician. It is also commonly used for diagnosing endometriosis at "atypical" sites such as the abdominal wall and scar endometriosis due to its convenience and accuracy when performed by a trained professional.30 Apart from the benefits of pre-operative mapping, identifying the etiology of symptoms can provide a therapeutic benefit for patients as seeing tangible evidence of their clinical problem holds potential validation power and can impact psychological symptom experience.31 Moreover, non-invasive diagnosis and staging enables informed decisions to be made regarding the patient’s following management.

Previously, TVS has been used by gynecologists to perform a “basic pelvic ultrasound” (Table 4) to visually assess the uterus, ovaries, and cul-de-sac. This technique has a high sensitivity for detecting ovarian endometriomas but is limited to only one form of endometriosis as the locations that are affected by SE and DE are not evaluated. In simple terms, if one does not look at a location, one cannot find the pathology that may be there. A major limitation with ultrasound at present is the skill to perform ultrasound at a level that can accurately diagnose endometriosis is not widely distributed.27 This is multifactorial but differences in healthcare systems geographically may be contributing to this, including the variations in how ultrasound is performed by sonographers versus sonologists.

4

Comparison of the basic pelvic ultrasound versus the advanced pelvic ultrasound.

Focus of Assessment | Basic Pelvic Ultrasound | Advanced Pelvic Ultrasound |

Uterus |

|

|

Ovaries |

|

|

Rectouterine pouch |

|

|

Ovarian mobility |

|

|

Rectouterine pouch adhesions (i.e. obliteration) |

|

|

Bladder |

|

|

Ureters |

|

|

Bowel |

|

|

Vagina |

|

|

Uterosacral ligaments |

|

|

Rectovaginal septum |

|

|

Site-specific tenderness |

|

|

The International Deep Endometriosis Analysis (IDEA) group, created and agreed upon by an international panel of endometriosis specialists, has inspired the adoption of the “advanced pelvic ultrasound”, which looks beyond the basic pelvic ultrasound and incorporates the assessment of the bowel, anterior (bladder, ureters, uterovesical junction) and posterior (posterior vaginal fornix, rectovaginal septum, USL) compartments.32 High diagnostic sensitivity and specificity has been reported when using TVS for diagnosing DE in the rectal/rectosigmoid region (sensitivity 89% and specificity 97%),33 USL (60% and 95%), rectovaginal septum (57% and 100%), vaginal (52%, 98%),34 and bladder (62% and 100%).35 Furthermore, Leonardi and colleagues found that ultrasound can accurately predict rASRM staging scores, allowing clinicians to devise management plans for patients earlier (more information on rASRM can be found in the Laparoscopy section).36 Similarly, ultrasound has been found to accurately predict the #Enzian surgical stage of endometriosis.37 The ultrasound-based endometriosis staging system (UBESS) is also being developed to triage patients to appropriately trained surgeons according to endometriosis complexity improving surgical planning.38,39

The IDEA ultrasound protocol comprises four main steps, which can be performed in any order:32

- Evaluating the uterus and adnexa (including a high-level inspection for signs of adenomyosis/presence or absence of endometrioma).

- Evaluation of transvaginal sonographic "soft markers" (i.e. site-specific tenderness (SST) and ovarian mobility).

- Assessment of status of POD using real-time ultrasound-based "sliding sign".40

- Assessment for DE nodules in anterior and posterior compartments.

When the uterus is visualized, the Morphological Uterus Sonographic Assessment (MUSA) consensus statement provides a useful framework for documenting findings and presence of adenomyosis.41,42 A uterus may exhibit an appearance like a question mark, known as the "question mark sign", when it is anteverted and retroflexed.43 Generally, this is secondary to the fundus adhering posteriorly to DE and/or adenomyosis with a disproportionately thickened posterior myometrium. While evaluating the adnexa, ovarian endometriomas or other ovarian abnormalities should be recorded according to the International Ovarian Tumor Analysis (IOTA) Group consensus.44 The most "common" endometrioma appearance is described as a homogenous, hypoechogenic unilocular cyst with fluid45 (ovarian endometrioma ultrasound video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AD20MUpBnV4). Furthermore, color Doppler energy may be used to increase diagnostic accuracy,46 primarily of non-endometrioma type ovarian cysts. Ovarian motility is another useful "soft marker", and reduced motility may indicate SE and/or DE.47,48 When ovaries appear fixed together, it is known as "kissing ovaries" and is associated with intra-abdominal adhesions and/or fallopian tube obstruction (especially in infertile patients).49

While SST falls under the second point in the IDEA approach, Leonardi and Condous recommend performing this test last to avoid early disruption or termination to the scan and patients should be warned that pain or discomfort may be elicited. Feedback from the patient is key to record SST properly.50

When assessing the bowel, hypoechoic nodules may be found in the upper (intraperitoneal) and lower (retroperitoneal) rectum. Since the lower rectum is outside the peritoneal cavity, and thus not accessible during laparoscopy, detection of nodules in this area can be valuable for pre-operative planning. On the other hand, it is extremely rare for lesions to exclusively affect the retroperitoneal rectum or rectovaginal septum. In the cases of severe endometriosis and POD obliteration, anatomical planes can be distorted, giving the impression that the nodules are retroperitoneal when in fact, they were formally intraperitoneal and have simply become invisible (i.e. beneath the surface) laparoscopically due to severe adhesions. The "sliding sign" to evaluate the POD obliteration state can be elicited with one hand holding the probe and the other on the patient’s lower abdomen. A "positive sign" is characterized by the rectum sliding against the uterus (exemplar video can be found at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UM3q4-GcjSQ), whereas movement of the rectum and uterus in unison ("negative sign") suggests POD obliteration (exemplar video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-60eQvEtYYM).

The other main areas of the posterior compartment are the USLs, the most common site of DE and SE, and the posterior vaginal fornix (PVF).51 The USL is around 12–14 cm long and extends caudally from the posterior cervix and vaginal dome to the sacrum.52 USL DE can be difficult to visualize laparoscopically as POD obliteration may obstruct the view highlighting the role of pre-operative imaging.53 If lesions are found, the extent of parametrial and/or torus uterinus (posterior insertion of USLs to the posterior cervix) should be assessed as well (detailed guide for ultrasound USL endometriosis diagnosis can be found at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ajum.12178).54 Compared to bowel endometriosis, TVS has lower sensitivity and other contrast mediums should be explored.33,34 The poorer diagnostic test performance for USL DE warrants adoption of new approaches to visualize these important structures. PVF endometriosis is suspected if the PVF is thickened or if a discrete nodule is found in the hypoechoic layer of the vaginal wall. Diagnostic potential of imaging for PVF is important but physical examination must also be used. The rectovaginal septum, while often thought of as a common place for DE, is indeed an unusual location. In addition to anatomical distortion that propagates confusion, nomenclature differences around the world may lead to some confusion. In some regions, posterior compartment DE is referred to as “rectovaginal” DE. The similarity of rectovaginal DE and rectovaginal septal DE permits this misunderstanding. While the use of the term rectovaginal DE made some sense in a world before imaging could better localize nodules in the distorted posterior compartment anatomical locations, it is a term that should now retire. Rectovaginal DE does not actually need to directly involve the rectum or vagina for the term to be used. In these cases, it is misleading what type of surgery is exactly needed to treat the disease.

When scanning the anterior compartment (bladder, ureters, uterovesical region), a relatively empty bladder enables visualization of lesions.55 DE most commonly infiltrates the muscular layer of the bladder wall especially near the base.50 Lesions appear spherical or comma-shaped and hyperechoic.55,56,57 Although rare, it is important to recognize ureteral endometriosis by routinely assessing the ureters on TVS.58,59,60 Dilation of the ureters can signify ureteral stenosis from DE and a transabdominal scan of the kidneys is needed to exclude hydroureteronephrosis.61 While not part of the IDEA statement, parametrial DE, often extended from the USLs,58,59,60 can be responsible for ureteral obstruction and should be assessed for as well.62,63

Diagnosing SE using ultrasound has been challenging due to its non-infiltrative (i.e. small) nature.48,64 However, a novel technique called "saline-infusion sonoPODography (SPG)" has been piloted with promising results (in those without DE, OE, or POD obliteration: accuracy 80.0%, sensitivity 77.7%, specificity 100.0%, positive predictive value 100.0%, negative predictive value 33.3%). This technique can be combined with hysterosalpingography in the infertility clinic to assess for uterine cavity abnormalities and tubal patency. In the study, a median of 60 ml of saline was infused into the POD through patent tubes but this amount should be validated in an outpatient setting. This provides an acoustic window enhancing contrast in the POD peritoneum improving visualization of superficial irregularities (i.e. SE) and superior RVS border (not possible without SPG) (video demonstration at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3trS-PBxyi4).65

Abdominal wall endometriosis can be scanned using a high-frequency linear probe along with Doppler examination. Lesions appear like DE of the posterior compartment (hypoechoic), but the majority of the nodules appear solid in nature with irregular/unclear borders surrounded by adipose tissue. Furthermore, when nodules are pressed with the probe, it may elicit SST.66

Transrectal ultrasound may also be used for assessing the pelvis for endometriosis and has the highest diagnostic accuracy for rectal DE compared to TVS and MRI, but TVS remains as the more common ultrasound approach because it is perceived as less invasive and it is more familiar.33,67 It is a reasonable approach to consider in those who cannot undergo a TVS. Like TVS, informed consent should be obtained for transrectal ultrasound.

Stand-Off Techniques and Image Optimization

Stand-off techniques involve the use of biological (e.g. filled bladder) or mechanical (e.g. saline or ultrasound gel) methods, introducing an acoustic window between the ultrasound probe and surrounding structures resulting in a clearer image. One example is sonovaginography, which involves the injection of ultrasound gel into the PVF.50 In an observational study with 28 patients, sonovaginography had a high sensitivity, specificity, and positive-predictive value (100%, 91.7%, 100%, respectively) for the detection of POD obliteration and DE.68 It also helps to identify how many layers of the posterior compartment (vagina, rectovaginal septum, anterior rectal wall) are affected for a more accurate diagnosis.

Bowel preparation may also be done prior to ultrasounds. Bowel preparation regimes differ, but may involve as much as a three-day low-residue diet and rectal enemas to clear the rectum to decrease potential artifacts caused by bowel loops, with some groups claiming it improves diagnostic performance.69 However, this requires more work from the patient, may not be well-tolerated, and other groups have not noted it to improve the diagnostic performance of TVS in detecting rectal endometriosis.70

MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a radiology technique that does not require ionizing radiation and provides clear images for analyzing soft tissue morphology. MRI is commonly utilized to evaluate for DE.71 In 2017, the European Society of Urogenital Radiology (ESUR), comprised of radiologists, gynecologists, and gynecological imaging experts from eight institutions, developed a clinical guideline for evaluating pelvic endometriosis with MRI.72 In a recent study by Indrielle-Kelly and colleagues, we have seen the adaptation of the IDEA consensus for MRI reporting.26 However, a review of 32 centers in 2020 found many inconsistencies in MRI protocols for endometriosis evaluation.73

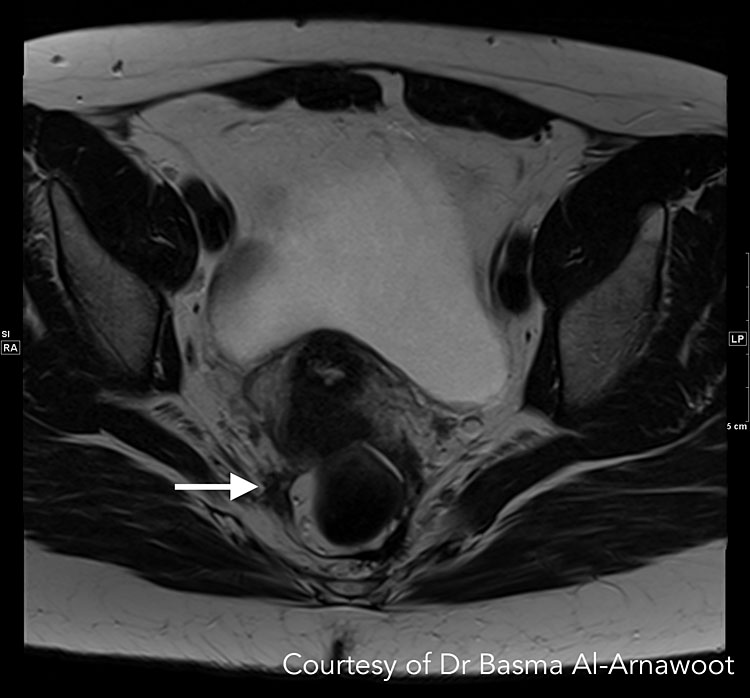

The T1- and T2-weighted two-dimensional fast spin-echo (FSE) are the most used sequences. The ESUR guidelines state that two-dimensional T2-weighted sequences taken in >2 orthogonal planes (sagittal, axial, oblique) from renal hila to pubic bone without fat-suppression is the best method for detecting pelvic endometriosis.74 When analyzing T2-weighted sequences, hypointense nodules with irregular borders suggest the presence of DE lesions, which contain fibrous tissue and dense smooth muscle (Figure 4 Case 1). Depending on the glandular tissue makeup of endometriosis implants, dilated endometrial glands may appear with hyperintense foci.75 A preliminary study by Bazot et al. suggests that three-dimensional (3D) sequences may also be considered since it can shorten the time required for imaging. Although 3D images of the pelvis are of poorer quality, it had similar diagnostic accuracy to multiplanar T2-weighted sequences in one study.76

A | B |

4

CASE 1. This is a patient who had endometriosis surgery 5 years prior and is currently presenting with pelvic pain and pain in the right extremity suspicious for neurological/sciatic nerve involvement. While the sciatic nerve trunk itself was not involved, MRI confirmed involvement of one of the sciatic nerve roots. (A) Axial T2-weighted MR image shows low-signal intensity stellate mass along the right pelvic wall (white arrow). When followed, the S3 nerve root is noted passing through this mass. (B) Corresponding sagittal T1-weighted MR images with fat suppression shows hyperintense foci indicating hemorrhage (white arrow), confirming that this is an endometriotic deposit as opposed to post-operative fibrosis. Courtesy of Dr Basma Al-Arnawoot.

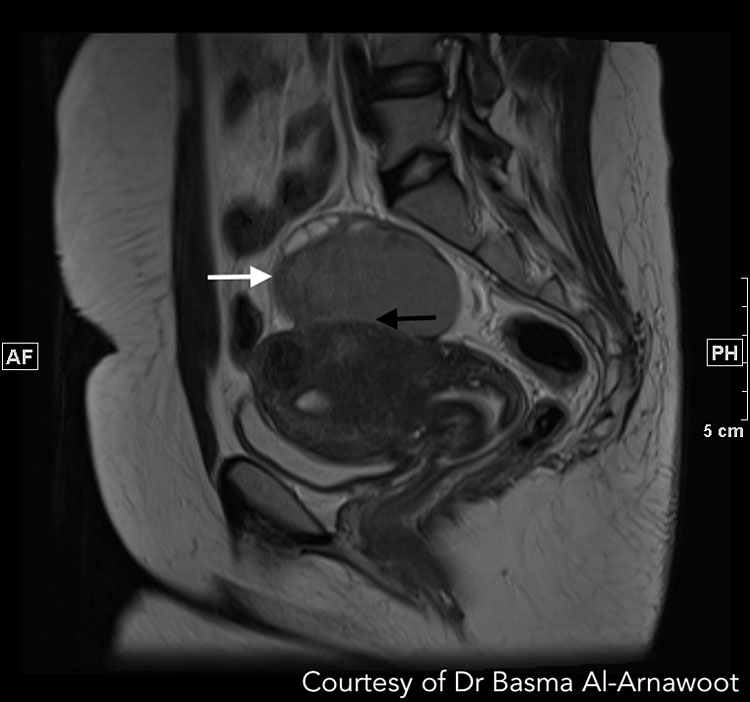

On the other hand, T1-weighted images can be used for diagnosing endometriotic cysts since blood products from recurrent bleeding displays hyperintense foci (Figure 5 Case 2).71 Additionally, fat suppression such as the Dixon technique or spectrally adiabatic inversion recovery increases tissue contrast facilitating the detection of cystic lesions.77,78

A | B |

5

CASE 2. A 32 year old with infertility and cystic lesions on ultrasound. (A) Axial T1-weighted MR image with fat suppression revealing a 7.2 cm T1 bright mass (white arrow) in the middle in keeping with a left ovarian endometrioma. (B) Sagittal T2-weighted MR image demonstrates the same endometrioma with the expected T2 intermediate signal intensity (white arrow) and reveals that it is adherent to the posterior serosal surface of the uterus (black arrow). Review of the remainder of the exam also revealed medialization of both ovaries and extensive Deep infiltrative endometriosis resulting in obliteration of the cul-de-sac (not visible on this image). Courtesy of Dr Basma Al-Arnawoot.

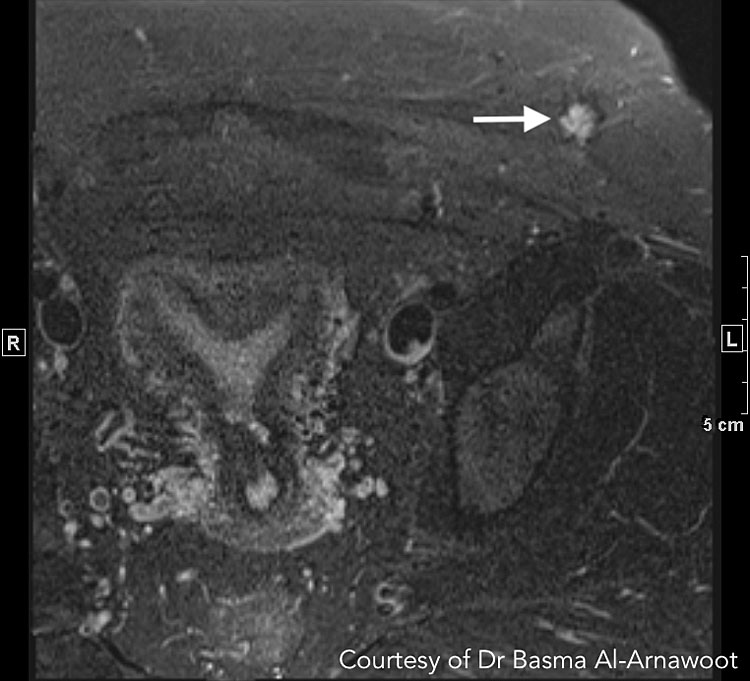

One of the main benefits of MRI is diagnosing endometriosis in areas difficult to access using other imaging modalities such as sciatic nerve involvement and extra-pelvic sites such as AWE (Figure 6 Case 3).79 For example, diaphragmatic lesions can have varying hyperintense appearances (deep nodules, punctate, spots, plaques) and are best visualized using the fat-suppressed T1-weighted sequences with an 83% sensitivity.80 A systematic review and meta-analysis by Guerriero and colleagues compared the diagnostic accuracy of TVS and MRI, and found similar performances in detecting endometriosis lesions in the posterior compartment.81 This has been recently confirmed in a series of diagnostic test accuracy meta-analyses by Gerges and colleagues.33,34 Of note, the same group of investigators found that MRI had a higher sensitivity for detecting USL and PVF DE (81% and 70%, respectively) compared to TVS (61% and 58%, respectively).34 However, MRI also has several limitations such as higher healthcare costs compared to ultrasound, limited availability, and possible patient discomfort, especially if certain image optimization strategies are used such as bowel preparation, stand-off techniques, and anti-peristaltic agents. Balancing all factors, the authors advocate for ultrasound to remain as the first-line imaging technique with advanced principles implemented while MRI would be beneficial for cases that extend beyond the potential of ultrasound, including cases of potentially extra-pelvic endometriosis or bulky, obscuring pelvic pathology making ultrasound more challenging.33,34

A | B |

6

CASE 3. A 28-year-old patient with enlarging left lower quadrant mass at the edge of a Pfannensteil incision from prior Cesarean section. MRI revealed that the mass corresponds to endometriotic deposits. (A) Axial T2-weighted MR image reveals a stellate nodule within the subcutaneous fat at the edge of the prior incision displaying increased T2 signal intensity (white arrow). It also has a very subtle T2 dark rim in keeping with hemosiderin deposition. (B) Axial T1-weighted MR image with fat suppression reveals T1 bright foci (white arrows) in keeping with hemorrhage. Courtesy of Dr Basma Al-Arnawoot.

Image Optimization

The timing of imaging in relation to the patient’s menstrual period remains inconclusive. Since endometriosis implants may bleed during menses, Fiaschetti et al. does not recommend performing T1-weighted sequences during the first 8 days of the menstrual cycle to avoid spontaneous hyperintensity.82 However, other studies found no significant difference in image quality regardless of the menstrual cycle phase and possible beneficial effects of pelvic free fluid facilitating image interpretation.83,84 The efficacy of rectal and/or vaginal opacification to identify DE using sonographic gel has also been debated as studies have shown variable results. If these techniques are used, bowel preparation is recommended to accurately identify lesions especially in the rectum.71 Lastly, administration of anti-peristaltic agents like butyl-scopolamine or hyoscine butylbromide can limit bowel motion artifacts to improve diagnostic accuracy.85

SURGERY AND PATHOLOGY

Surgery and pathology work hand in hand since samples must be collected first before they can be analyzed. Since the appearance of endometriotic lesions (discussed below) have high variability between patients, surgeons often "over-biopsy". A recent validation study by Gratton and colleagues found that laparoscopic visualization had a high sensitivity (90%) while the specificity was 40%.86 Low specificity when diagnostic laparoscopy is performed alone had also been reported by previous studies highlighting the importance of a histological diagnosis.87 However, a negative diagnostic laparoscopy is helpful in excluding endometriosis.88 Hence, surgery and pathology will be discussed together within this section.

LAPAROSCOPY

Laparoscopy is a minimally invasive procedure often alongside histopathological confirmation for diagnosing all types of pelvic endometriosis (ovarian endometriomas, DE, SE) since surgeons can directly visualize the pelvic and abdominal cavity. In 2022, ESHRE no longer considered laparoscopy as the "gold standard" and recommends its use if initial imaging results are negative and/or patients are not suitable/unresponsive to empirical treatment.23 Depending on the goal, during the same operation, surgeons could also aim for complete treatment of endometriotic lesions to provide symptomatic control and reduce the number of laparoscopies (which carries its own risks). Herein lies the issue with surgery as the diagnostic test of choice – many patients exhibit endometriosis that cannot be appropriately managed at a surgery that is simultaneously diagnostic. Either the surgery is not planned for long enough, the surgical skill of the surgeon is insufficient for the complexity of the endometriosis identified, or the patient has not fully consented to what could/should happen based on what is found.28 As such, the concept of laparoscopy being the gold standard is increasingly being challenged.39,89

Laparoscopy for endometriosis should always involve a comprehensive exploration of the abdominal and pelvic contents. The traditional contents of the pelvis including ovarian, uterine surface, fallopian tubes and peritoneum need to be adequately surveyed. In order to identify subtle lesions, the laparoscope must be brought right up to the surfaces being inspected. In addition, the gastrointestinal and genitourinary systems need to be assessed as well, including the appendix. The diaphragm should routinely be inspected, especially if the patient describes right upper quadrant symptoms. If the patient underwent pre-operative ultrasound/MRI where endometriosis was visualized, these areas should be closely inspected surgically. In some situations, endometriosis may not be obviously visible at laparoscopy despite clear identification with imaging.90

SE has been described to have a black (“powder burn”) or dark bluish appearance from the accumulation of blood pigments.91 However, subtle forms can appear as white opacifications, red flamelike lesions, or yellow-brown patches in earlier, active stages of disease.92 Ovarian endometriomas have a distinct morphology classically described as a "chocolate cyst" containing old menstrual blood giving it a dark brown appearance. Adhesions are often found in association with endometriomas and consists of fibrous scar tissue because of chronic inflammation. In many cases, there is endometriosis at the site of ovarian fixation.47,48 Like an imaging-based assessment following the IDEA protocol, the posterior and anterior compartments should be assessed carefully for DE. Often times, DE appears as multifocal nodules and may infiltrate the surrounding viscera and peritoneal tissue.93 As mentioned earlier, depending on the extent of POD obliteration, posterior compartment (USL, bowel, PVF) DE may be difficult to assess and diagnose surgically, with evidence supporting a better diagnostic test performance using non-invasive imaging-based assessment for this specific type of DE.53 An atlas of endometriosis appearances can be at https://www.glowm.com/atlas-page-special/atlasid/Endometriosis.html.

When combining diagnostic laparoscopy with operative laparoscopy, the surgeon must consider the importance of a biopsy to ensure their visual diagnosis is indeed correct. There is ample evidence that surgeons overcall endometriosis at surgery.86,87,88 In the cases where surgeons perform excision of endometriosis, all specimens should be sent to pathology for analysis. In some cases, it is inappropriate to use biopsy as a diagnostic test. For example, in a patient who undergoes diagnostic laparoscopy and the surgeon suspects bowel DE, this area should only be biopsied/excised if the patient explicitly provided informed consent following a discussion about the benefits and risks of a “bowel surgery” component and the patient was adequately prepared with bowel preparation and antibiotic prophylaxis. Surgeons should also consider concurrent appendectomy during excision of endometriosis since women with DE have a high risk of appendiceal endometriosis.94 Often, appendectomy is not within the skill set of gynecologists, which again creates a unique challenge with surgery being used as a combined diagnostic test and treatment modality.

Surgical Diagnosis for Extra-pelvic Endometriosis

Although non-invasive imaging techniques (i.e. chest x-ray, CT, MRI) exist, they have low sensitivity. Hence, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) is the "gold standard" for diagnosing thoracic endometriosis. In a systematic review of women with catamenial pneumothorax, thoracic endometriosis and diaphragmatic lesions were detected in 52.1% and 38.8% of women, respectively, following VATS.95 Like laparoscopy, excision of endometriosis lesions can be considered if found for both diagnostic and therapeutic value, and the previously used exploratory thoracotomy should be reserved if minimally invasive techniques are inadequate. VATS will not be able to diagnose endometriosis affecting the abdominal side of the diaphragm. This requires laparoscopy, occasionally with manipulation of the liver to adequately inspect the diaphragm, especially when clinical symptoms exist. It is unclear if there is any clinical utility in diagnosing and surgically treating diaphragmatic endometriosis in patients who are asymptomatic (in the RUQ/chest region). It is essential to recall that in both VATS and laparoscopy, diagnosis is operating dependent, with individuals more familiar with extra-pelvic endometriosis better equipped to recognize (sometimes) subtle abnormalities and when needed, surgically biopsy/treat them as well.

Enhanced Intra-Operative Techniques

Conventional laparoscopy uses white light when exploring the pelvic cavity. However, three novel intra-operative methods have been explored to improve detection of peritoneal endometriosis: narrow-band imaging (NBI), autofluorescence (AFI), and 5-aminolevulinic acid induced fluorescence (5-ALA).96 Both NBI and AFI work by detecting increased neovascularization, which is associated with endometriotic tissue while 5-ALA accentuates damaged tissue.97,98,99 However, their benefits are limited to a few studies and more research is being done to better understand their use.96

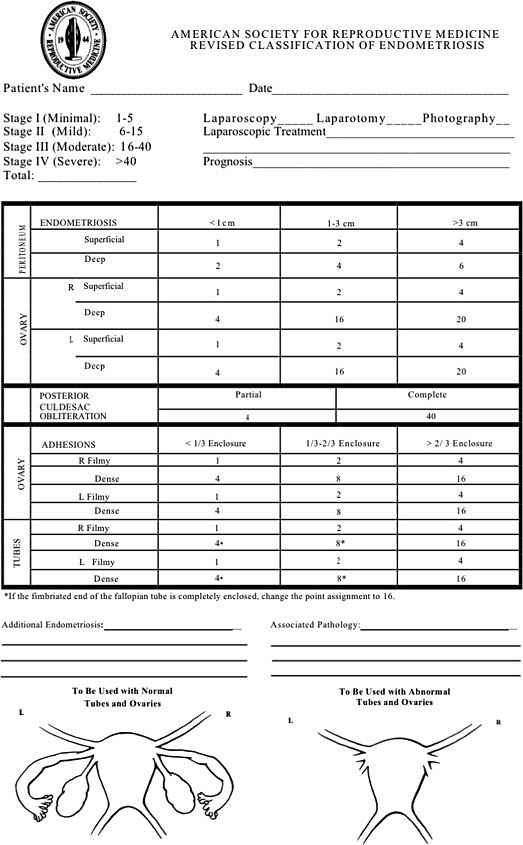

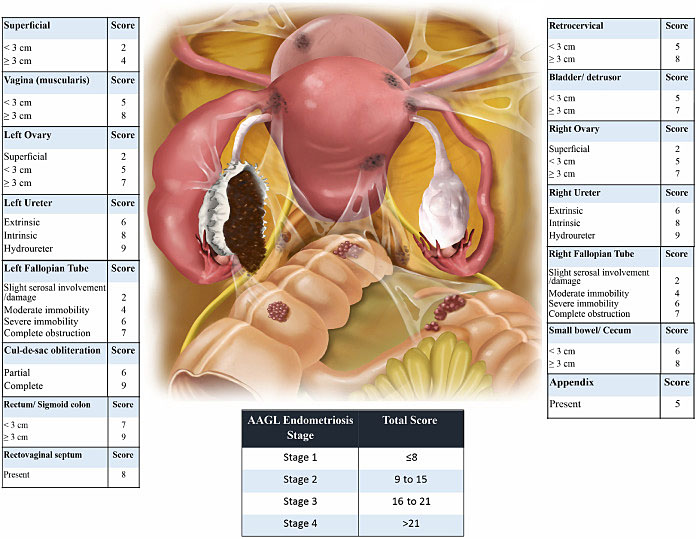

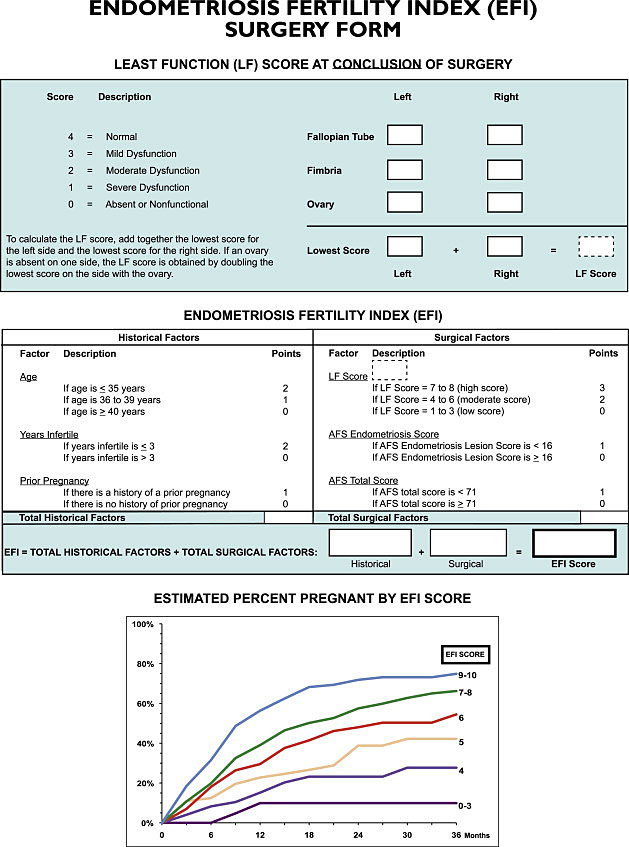

Surgical Staging Methods

In 2017, the World Endometriosis Society consensus for diagnosis endometriosis recommended the use of the rASRM classification tool during surgery to classify endometriosis based on the size, extent, and location of lesions found (Figure 7).100 There are four stages ranging from minimal (Stage 1), mild (Stage 2), moderate (Stage 3), and severe (Stage 4).100,101 However, a prospective analysis found considerable inter-variability among surgeons reducing its diagnostic accuracy. In 2021, the AAGL Special Interest Group in Endometriosis published the AAGL Classification Tool solely based on intraoperative findings to better quantify the surgical complexity of endometriosis cases (Figure 8). Like the rASRM system, there are four AAGL endometriosis stages. However, the recent validation study found higher reproducibility with the AAGL score (kappa = 0.621) compared to rASRM (kappa = 0.317) when discriminating surgical complexity.102 The rASRM system fails to properly incorporate DE, which often equates to surgical complexity, leading to this deficiency in the system. The Enzian classification tool has been introduced in recent years to better describe DE, and has recently introduced the updated system, #Enzian, which also incorporates SE and tubal pathology (Figure 9).100,103 A recent study by Montanari and colleagues demonstrates that the #Enzian system score can be accurately predicted with ultrasound, increasing the utility of this model significantly.37 The Endometriosis Fertility Index (EFI), reliant on the rASRM staging system, was also recommended after surgical staging/treatment for women considering pregnancy in the future (Figure 10).100,104 Although several staging tools exist, they mainly focus on the physical extent of disease and do not correlate well with the pain symptoms and impact on quality of life for patients.105 Beyond accurately representing the experience of the patient, there should be functionality to prognosticate clinical outcomes, which currently only the EFI attempts to do. The utility of the newest system, the AAGL Classification Tool, remains to be seen but it must be validated.106

7

The revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine classification tool is the most commonly used staging system and categorizes endometriosis into four stages: minimal (Stage 1), mild (Stage 2), moderate (Stage 3), and severe (Stage 4). Reproduced with permission.101

8

The new AAGL tool utilizes intra-operative anatomical findings to differentiate endometriosis by surgical complexity. Reproduced with permission.102

9

The #Enzian classification tool aims to better describe deep endometriosis, although more external validation is required. Reproduced with permission.103

10

The Endometriosis Fertililty Index (EFI) is an externally validated tool used to predict spontaneous pregnancy without assisted reproductive techniques following surgical treatment. Reproduced with permission.104

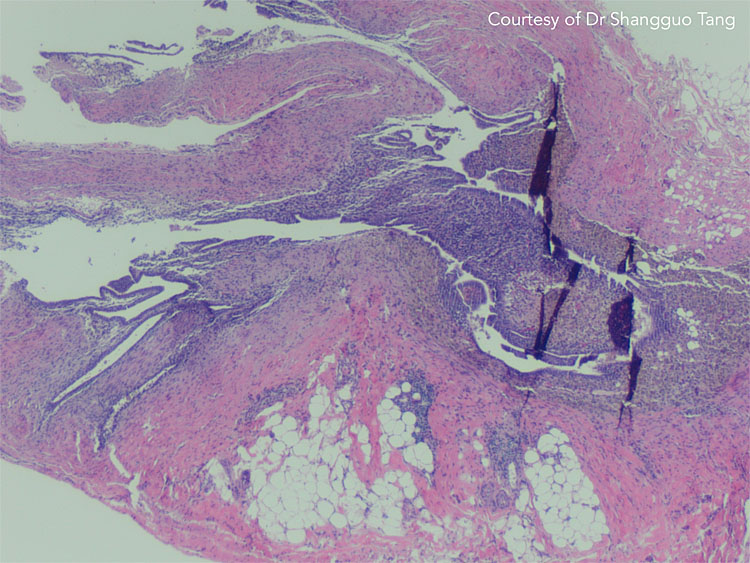

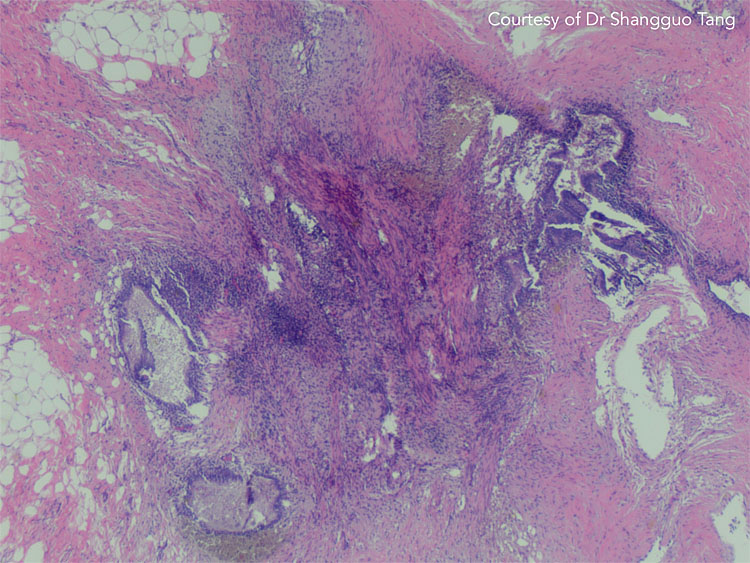

PATHOLOGY

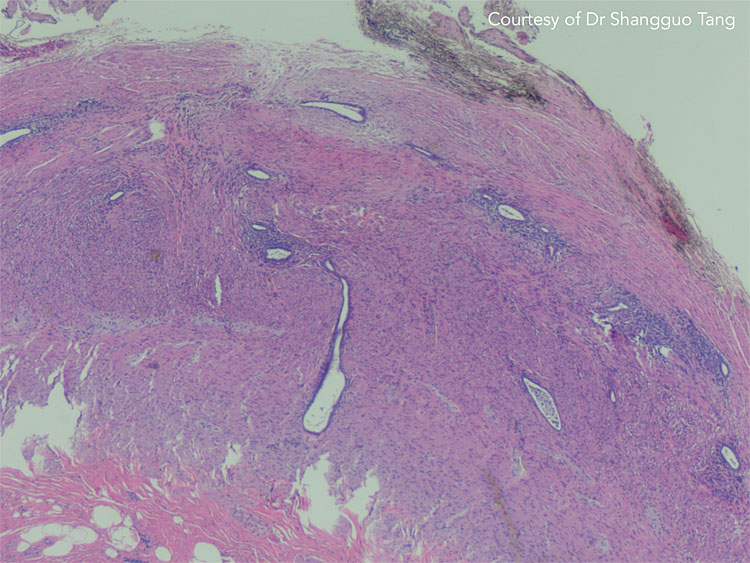

During laparoscopy, several biopsies of lesions suggestive of endometriosis should be taken and submitted to pathology. In extra-pelvic endometriosis like AWE, imaging techniques used (i.e. USS, MRI, CT) may detail the extent of disease, but are sometimes unable to differentiate abdominal masses from neoplasms, abscesses, or hematomas.16 Furthermore, AWE cannot be visualized laparoscopically and specimens can be retrieved using ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration or core needle biopsy (Figure 11).107 Depending on the context, histopathological confirmation should be ascertained to reach a definitive diagnosis and decide the appropriate management plan. Again, this can sometimes be challenged by the desire to simultaneously diagnose and treat. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) suggests, in general, that the presence of two or more of the following features must be detected in specimens in order to confirm endometriosis: endometrial epithelium, endometrial glands, endometrial stroma, hemosiderin-laden macrophages (Figure 12).108 However, the standard pathological protocol may also contribute to the underdiagnosis of endometriosis, especially for appendiceal endometriosis (Figure 13). A modified pathological analysis with serial sectioning and evaluation of the appendix and mesoappendix can significantly improve the detection of more abnormal pathology.109 One may extrapolate the results of this study to other specimens where 'in toto' assessment (submitting the entire specimen for microscopic analysis) will improve the diagnostic potential of histolopathology. Histological diagnosis of endometriosis is mainly limited by the surgeon’s ability to correctly identify endometriotic lesions due to more subtle/atypical appearances and submitting suspicious lesions to histology may help reduce this risk.86 On the other hand, a more liberal biopsy/excision approach may reduce the specificity of surgical visualization and may institute unnecessary surgical risk.

11

Abdominal wall endometriosis on histology. Courtesy of Dr Shangguo Tang.

12

Histology of endometriosis biopsy with endometrial epithelium, endometrial glands, endometrial stroma, and hemosiderin-laden macrophages. Courtesy of Dr Shangguo Tang.

13

Appendiceal endometriosis on histology. Courtesy of Dr Shangguo Tang.

Compared to pelvic endometriosis, thoracic/diaphragm endometriosis does not commonly contain endometrial glands on histology adding to the diagnostic challenge.110,111 Furthermore, only a small focus of endometriotic tissue may be found for biopsy. The fewer samples available and less obvious features of endometriosis on histology can make this diagnosis overlooked by pathologists unfamiliar to thoracic endometriosis.110 Immunohistochemical analysis can be used concurrently to improve the diagnostic accuracy of thoracic endometriosis. Several studies have found improved detection of thoracic endometrial cells when tissue stained positive for estrogen receptor (88%), progesterone receptor (100%), and CD10 (88%) on immunohistochemical staining.110,111,112

BIOMARKERS

Many research studies and Cochrane reviews have investigated potential biomarkers that can be used to detect endometriosis,10,11,12 with an appropriate goal of reducing the diagnostic delay that exists in diagnosing endometriosis. Unfortunately, all of these are often non-specific/unreliable making them inappropriate for routine clinical use. In this section, the main biomarkers used in clinic will be discussed as well as a brief overview of biomarkers currently being studied academically.

Clinical Use of CA-125

The Cancer Antigen 125 (CA-125) biomarker has been the most researched biomarker for endometriosis. Most laboratory tests have set a CA-125 cut-off at 35 units/ml to suggest the possibility of endometriosis.113 Although serological CA-125 levels may be raised in some cases of endometriosis, the 2016 Cochrane review by Nisenblat and colleagues found that CA-125 had a poor specificity and sensitivity for detecting endometriosis.10 Another limitation of CA-125 is that raised levels are associated with many other physiological and pathological conditions including menstruation, pregnancy, fibroids, and most notably, ovarian cancer.114,115,116 Given its several limitations, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), The Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada (SOGC), ESHRE, and ACOG guidelines currently do not recommend the use of CA-125 as a diagnostic tool for endometriosis.4,117,118,119 When used clinically, an elevated CA-125 may lead patients down a path of unnecessary, risky, and anxiety-provoking investigations and procedures. Unless there are suspicious features for ovarian malignancy in the context of endometriomas diagnosed on imaging (based on IOTA nomenclature), CA-125 is not of additional value since the diagnosis is already made by the imaging test, leaving the CA-125 as only a potential harm-causing test.

Academic Use

As mentioned earlier, many research articles have investigated the use of biomarkers from blood, urine, menstrual effluent, and peritoneal fluid as alternative diagnostic techniques for endometriosis.10,11,12 Some of the more popular biomarkers include inflammatory cytokines, angiogenic factors, reactive oxygen species, microRNA, and matrix metalloproteinases.120,121,122 However, the heterogeneity and overall low quality of studies limits the applicability of findings in clinical practice, and higher quality research is warranted.11

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

Clinical Diagnosis

- A comprehensive history and thorough physical examination can aid clinicians in making a presumptive clinical diagnosis

- Endometriosis can present with a wide range of symptoms depending on the site of lesions

- Co-existing pain-generating mechanisms and/or central sensitization with endometriosis should be managed; the Central Sensitization Inventory questionnaire score can be used

- Clinical assessment is subject to operator skill and knowledge in the history taking/physical examination

- If clinical examination is normal but endometriosis is suspected, imaging techniques should be sought

Imaging

- Ultrasound and MRI can be used pre-operatively to accurately diagnose ovarian and deep endometriosis pre-operatively; these imaging modalities may be complementary

- Ultrasound and MRI have similar diagnostic accuracy for pelvic endometriosis

- The International Deep Endometriosis Analysis (IDEA) ultrasound protocol goes beyond the basic pelvic ultrasound and is highly sensitive and specific for diagnosing ovarian endometrioma(s) and deep endometriosis

- Saline-infusion sonoPODography is a novel technique that can diagnose SE on ultrasound, but requires validation

- The ultrasound-based endometriosis staging system (UBESS) has been developed to triage patients using ultrasound based on disease complexity

- According to ESUR guidelines, the two-dimensional T2-weighted sequences without fat suppression is the best method for diagnosing endometriosis on MRI

- MRI can be used for more complex cases involving extra-pelvic/difficult to access sites

- Imaging tests are subject to operator skill in performance of imaging test and interpretation

Surgery and Pathology

- Laparoscopy is a minimally invasive procedure, which can diagnose all types of endometriosis alongside histopathological confirmation

- Peritoneal endometriosis classically appears as black or "powder-burn" appearances although more subtle forms (white, red, yellow-brown) can exist

- Ovarian endometriomas appear as "chocolate cysts" containing old menstrual blood

- Depending on patient goals, surgeons should aim for complete treatment of endometriosis if found during laparoscopy but biopsy must be obtained to utilize histopathology as the final diagnostic test method since surgeons do not have perfect diagnostic accuracy

- The revised American Society of Reproductive Medicine (rASRM) staging system is the most used, but newer tools (Enzian tool, AAGL tool) have been developed and should be validated

- The Endometriosis Fertility Index (EFI), based on the rASRM system, can be used to predict spontaneous pregnancy post-operatively

- Current endometriosis staging systems poorly represent the severity of symptoms or impact on quality of life for the patient

- Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) is the "gold standard" for diagnosing thoracic endometriosis

- Histopathological confirmation of endometriosis is achieved in the presence of two or more features: endometrial epithelium, endometrial glands, endometrial stroma, hemosiderin-laden macrophages

- Histopathology is subject to variability in operator diagnostic performance

Biomarkers

- CA-125 is not recommended for diagnosing endometriosis

- Reliable biomarkers for endometriosis have not yet been discovered and is not recommended for use outside of the academic research settings

- Future research may explore serum, menstrual effluent, urine, or peritoneal fluid for potential biomarkers

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Dr Basma Al-Arnawoot and Dr Shangguo Tang at McMaster University in the Departments of Radiology and Pathology, respectively, for providing case images.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Kevin Kuan declares that they have no interests that conflict with the contents of this chapter. Mathew Leonardi reports personal fees from GE Healthcare, TerSera, Bayer, AbbVie, grants from Australian Women and Children’s Research Foundation, Endometriosis Australia, CanSAGE, Hamilton Health Sciences, HyIvy Health, all outside of the work of this chapter.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

REFERENCES

Zondervan KT, Becker CM, Missmer SA. Endometriosis. New England Journal of Medicine 2020;382(13):1244–56. | |

Nisolle M, Donnez J. Peritoneal endometriosis, ovarian endometriosis, and adenomyotic nodules of the rectovaginal septum are three different entities. Fertil Steril. 1997 Oct;68(4):585-96. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(97)00191-x. PMID: 9341595 | |

Vermeulen N, Abrao MS, Einarsson JI, et al. Endometriosis Classification, Staging and Reporting Systems: A Review on the Road to a Universally Accepted Endometriosis Classification. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2021;28(11):1822–48. | |

Endometriosis: diagnosis and management (NICE guideline NG73) [Internet]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2017. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng73/chapter/recommendations. | |

Chapron C, Fauconnier A, Dubuisson JB, et al. Deep infiltrating endometriosis: relation between severity of dysmenorrhoea and extent of disease. Human Reproduction 2003;18(4):760–6. | |

Seear K. The etiquette of endometriosis: stigmatisation, menstrual concealment and the diagnostic delay. Soc Sci Med 2009;69(8):1220–7. | |

Nnoaham KE, Hummelshoj L, Webster P, et al. Impact of endometriosis on quality of life and work productivity: a multicenter study across ten countries. Fertil Steril 2011;96(2):366–73.e8. | |

Ahmad G, Baker J, Finnerty J, et al. Laparoscopic entry techniques. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019;1(1):Cd006583. | |

Nisenblat V, Bossuyt PM, Farquhar C, et al. Imaging modalities for the non-invasive diagnosis of endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;2(2):Cd009591. | |

Nisenblat V, Bossuyt PM, Shaikh R, et al. Blood biomarkers for the non-invasive diagnosis of endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;2016(5):Cd012179. | |

Gupta D, Hull ML, Fraser I, et al. Endometrial biomarkers for the non-invasive diagnosis of endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;4(4):Cd012165. | |

Liu E, Nisenblat V, Farquhar C, et al. Urinary biomarkers for the non-invasive diagnosis of endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;2015(12):Cd012019. | |

Agarwal SK, Chapron C, Giudice LC, et al. Clinical diagnosis of endometriosis: a call to action. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2019;220(4):354.e1–.e12. | |

Missmer SA, Hankinson SE, Spiegelman D, et al. Reproductive history and endometriosis among premenopausal women. Obstet Gynecol 2004;104(5 Pt 1):965–74. | |

Andres MP, Arcoverde FVL, Souza CCC, et al. Extrapelvic Endometriosis: A Systematic Review. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2020;27(2):373–89. | |

Machairiotis N, Stylianaki A, Dryllis G, et al. Extrapelvic endometriosis: a rare entity or an under diagnosed condition? Diagnostic Pathology 2013;8(1):194. | |

Quaas A, Dokras A. Diagnosis and treatment of unexplained infertility. Rev Obstet Gynecol 2008;1(2):69–76. | |

Lee HJ, Lee JE, Ku S-Y, et al. Natural conception rate following laparoscopic surgery in infertile women with endometriosis. Clin Exp Reprod Med 2013;40(1):29–32. | |

Diagnostic evaluation of the infertile female: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril 2015;103(6):e44–50. | |

Orr NL, Wahl KJ, Lisonek M, et al. Central sensitization inventory in endometriosis. Pain 2021. | |

Riazi H, Tehranian N, Ziaei S, et al. Clinical diagnosis of pelvic endometriosis: a scoping review. BMC Womens Health 2015;15:39. | |

Hudelist G, Oberwinkler KH, Singer CF, et al. Combination of transvaginal sonography and clinical examination for preoperative diagnosis of pelvic endometriosis. Human Reproduction 2009;24(5):1018–24. | |

Group TmotEGC, Becker CM, Bokor A, Heikinheimo O, Horne A, Jansen F, et al. ESHRE guideline: endometriosis†. Human Reproduction Open. 2022;2022(2 | |

Tissot M, Lecointre L, Faller E, et al. Clinical presentation of endometriosis identified at interval laparoscopic tubal sterilization: Prospective series of 465 cases. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod 2017;46(8):647–50. | |

Matorras R, Rodríguez F, Pijoan JI, et al. Are there any clinical signs and symptoms that are related to endometriosis in infertile women? Am J Obstet Gynecol 1996;174(2):620–3. | |

Indrielle-Kelly T, Frühauf F, Fanta M, et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Ultrasound and MRI in the Mapping of Deep Pelvic Endometriosis Using the International Deep Endometriosis Analysis (IDEA) Consensus. BioMed Research International 2020;2020:3583989. | |

Leonardi M, Robledo KP, Goldstein SR, et al. International survey finds majority of gynecologists are not aware of and do not utilize ultrasound techniques to diagnose and map endometriosis. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology 2020;56(3):324–8. | |

Leonardi M, Singh SS, Murji A, et al. Deep Endometriosis: A Diagnostic Dilemma With Significant Surgical Consequences. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2018;40(9):1198–203. | |

Rousset P, Rousset-Jablonski C, Alifano M, et al. Thoracic endometriosis syndrome: CT and MRI features. Clin Radiol 2014;69(3):323–30. | |

Guerriero S, Conway F, Pascual MA, et al. Ultrasonography and Atypical Sites of Endometriosis. Diagnostics 2020;10(6):345. | |

Young K, Fisher J, Kirkman M. Women's experiences of endometriosis: a systematic review and synthesis of qualitative research. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care 2015;41(3):225–34. | |

Guerriero S, Condous G, van den Bosch T, et al. Systematic approach to sonographic evaluation of the pelvis in women with suspected endometriosis, including terms, definitions and measurements: a consensus opinion from the International Deep Endometriosis Analysis (IDEA) group. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology 2016;48(3):318–32. | |

Gerges B, Li W, Leonardi M, et al. Optimal imaging modality for detection of rectosigmoid deep endometriosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2021;58(2):190–200. | |

Gerges B, Li W, Leonardi M, et al. Meta-analysis and systematic review to determine the optimal imaging modality for the detection of uterosacral ligaments/torus uterinus, rectovaginal septum and vaginal deep endometriosis. Hum Reprod Open 2021;2021(4):hoab041. | |

Guerriero S, Ajossa S, Minguez JA, et al. Accuracy of transvaginal ultrasound for diagnosis of deep endometriosis in uterosacral ligaments, rectovaginal septum, vagina and bladder: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology 2015;46(5):534–45. | |

Leonardi M, Espada M, Choi S, et al. Transvaginal Ultrasound Can Accurately Predict the American Society of Reproductive Medicine Stage of Endometriosis Assigned at Laparoscopy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2020;27(7):1581–7.e1. | |

Montanari E, Bokor A, Szabó G, et al. Accuracy of sonography for non-invasive detection of ovarian and deep endometriosis using #Enzian classification: prospective multicenter diagnostic accuracy study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2021. | |

Tompsett J, Leonardi M, Gerges B, et al. Ultrasound-Based Endometriosis Staging System: Validation Study to Predict Complexity of Laparoscopic Surgery. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2019;26(3):477–83. | |

Menakaya U, Reid S, Lu C, et al. Performance of ultrasound-based endometriosis staging system (UBESS) for predicting level of complexity of laparoscopic surgery for endometriosis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2016;48(6):786–95. | |

Reid S, Lu C, Casikar I, et al. Prediction of pouch of Douglas obliteration in women with suspected endometriosis using a new real-time dynamic transvaginal ultrasound technique: the sliding sign. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2013;41(6):685–91. | |

Van den Bosch T, Dueholm M, Leone FP, et al. Terms, definitions and measurements to describe sonographic features of myometrium and uterine masses: a consensus opinion from the Morphological Uterus Sonographic Assessment (MUSA) group. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2015;46(3):284–98. | |

Harmsen MJ, Van den Bosch T, de Leeuw RA, et al. Consensus on revised definitions of morphological uterus sonographic assessment (MUSA) features of adenomyosis: results of a modified Delphi procedure. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2021. | |

Di Donato N, Bertoldo V, Montanari G, et al. Question mark form of uterus: a simple sonographic sign associated with the presence of adenomyosis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2015;46(1):126–7. | |

Timmerman D, Valentin L, Bourne TH, et al. Terms, definitions and measurements to describe the sonographic features of adnexal tumors: a consensus opinion from the International Ovarian Tumor Analysis (IOTA) Group. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2000;16(5):500–5. | |

Van Holsbeke C, Van Calster B, Guerriero S, et al. Endometriomas: their ultrasound characteristics. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2010;35(6):730–40. | |

Guerriero S, Ajossa S, Mais V, et al. The diagnosis of endometriomas using colour Doppler energy imaging. Hum Reprod 1998;13(6):1691–5. | |

Rao T, Condous G, Reid S. Ovarian Immobility at Transvaginal Ultrasound: An Important Sonographic Marker for Prediction of Need for Pelvic Sidewall Surgery in Women With Suspected Endometriosis. J Ultrasound Med 2021. | |

Reid S, Leonardi M, Lu C, et al. The association between ultrasound-based 'soft markers' and endometriosis type/location: A prospective observational study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2019;234:171–8. | |

Ghezzi F, Raio L, Cromi A, et al. "Kissing ovaries": a sonographic sign of moderate to severe endometriosis. Fertil Steril 2005;83(1):143–7. | |

Leonardi M, Condous G. How to perform an ultrasound to diagnose endometriosis. Australasian Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine 2018;21(2):61–9. | |

Chapron C, Fauconnier A, Vieira M, et al. Anatomical distribution of deeply infiltrating endometriosis: surgical implications and proposition for a classification. Hum Reprod 2003;18(1):157–61. | |

Vu D, Haylen BT, Tse K, et al. Surgical anatomy of the uterosacral ligament. Int Urogynecol J 2010;21(9):1123–8. | |

Leonardi M, Condous G. A pictorial guide to the ultrasound identification and assessment of uterosacral ligaments in women with potential endometriosis. Australasian Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine 2019;22(3):157–64. | |

Leonardi M, Martins WP, Espada M, et al. Proposed technique to visualize and classify uterosacral ligament deep endometriosis with and without infiltration into parametrium or torus uterinus. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2020;55(1):137–9. | |

Leonardi M, Espada M, Kho RM, et al. Endometriosis and the Urinary Tract: From Diagnosis to Surgical Treatment. Diagnostics (Basel) 2020;10(10):771. | |

Maccagnano C, Pellucchi F, Rocchini L, et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Bladder Endometriosis: State of the Art. Urologia Internationalis 2012;89(3):249–58. | |

Fedele L, Bianchi S, Raffaelli R, et al. Pre-operative assessment of bladder endometriosis. Hum Reprod 1997;12(11):2519–22. | |

Ong J, Leonardi M, Espada M, et al. Ureter Visualization With Transvaginal Ultrasound: A Learning Curve Study. J Ultrasound Med 2020;39(12):2365–72. | |

Pateman K, Holland TK, Knez J, et al. Should a detailed ultrasound examination of the complete urinary tract be routinely performed in women with suspected pelvic endometriosis? Hum Reprod 2015;30(12):2802–7. | |

Aas-Eng MK, Salama M, Sevelda U, et al. Learning curve for detection of pelvic parts of ureters by transvaginal sonography: feasibility study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2020;55(2):264–8. | |

Carmignani L, Vercellini P, Spinelli M, et al. Pelvic endometriosis and hydroureteronephrosis. Fertil Steril 2010;93(6):1741–4. | |

Carfagna P, De Cicco Nardone C, De Cicco Nardone A, et al. Role of transvaginal ultrasound in evaluation of ureteral involvement in deep infiltrating endometriosis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2018;51(4):550–5. | |

Guerriero S, Martinez L, Gomez I, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of transvaginal sonography for detecting parametrial involvement in women with deep endometriosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2021;58(5):669–76. | |

Robinson AJ, Rombauts L, Ades A, et al. Poor sensitivity of transvaginal ultrasound markers in diagnosis of superficial endometriosis of the uterosacral ligaments. Journal of Endometriosis and Pelvic Pain Disorders 2018;10(1):10–7. | |

Leonardi M, Robledo KP, Espada M, Vanza K, Condous G. SonoPODography: A new diagnostic technique for visualizing superficial endometriosis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020 Nov;254:124-131. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.08.051. Epub 2020 Sep 16. PMID: 32961428 | |

Savelli L, Manuzzi L, Di Donato N, et al. Endometriosis of the abdominal wall: ultrasonographic and Doppler characteristics. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology 2012;39(3):336–40. | |

Piketty M, Chopin N, Dousset B, et al. Preoperative work-up for patients with deeply infiltrating endometriosis: transvaginal ultrasonography must definitely be the first-line imaging examination. Hum Reprod 2009;24(3):602–7. | |

Reid S, Winder S, Condous G. Sonovaginography: redefining the concept of a "normal pelvis" on transvaginal ultrasound pre-laparoscopic intervention for suspected endometriosis. Australasian Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine 2011;14(2):21–4. | |

Ros C, Rius M, Abrao MS, et al. Bowel preparation prior to transvaginal ultrasound improves detection of rectosigmoid deep infiltrating endometriosis and is well tolerated: prospective study of women with suspected endometriosis without surgical criteria. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology 2021;57(2):335–41. | |

Ferrero S, Scala C, Stabilini C, et al. Transvaginal sonography with vs. without bowel preparation in diagnosis of rectosigmoid endometriosis: prospective study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2019;53(3):402–9. | |

Bazot M, Bharwani N, Huchon C, et al. European society of urogenital radiology (ESUR) guidelines: MR imaging of pelvic endometriosis. Eur Radiol 2017;27(7):2765–75. | |

Bazot M, Bharwani N, Huchon C, et al. European society of urogenital radiology (ESUR) guidelines: MR imaging of pelvic endometriosis. Eur Radiol 2017;27(7):2765–75. | |

Wild M, Pandhi S, Rendle J, et al. MRI for the diagnosis and staging of deeply infiltrating endometriosis: a national survey of BSGE accredited endometriosis centres and review of the literature. Br J Radiol 2020;93(1114):20200690. | |

Bazot M, Darai E, Hourani R, et al. Deep pelvic endometriosis: MR imaging for diagnosis and prediction of extension of disease. Radiology 2004;232(2):379–89. | |

Schneider C, Oehmke F, Tinneberg HR, et al. MRI technique for the preoperative evaluation of deep infiltrating endometriosis: current status and protocol recommendation. Clinical Radiology 2016;71(3):179–94. | |

Bazot M, Stivalet A, Daraï E, et al. Comparison of 3D and 2D FSE T2-weighted MRI in the diagnosis of deep pelvic endometriosis: preliminary results. Clin Radiol 2013;68(1):47–54. | |

Togashi K, Nishimura K, Kimura I, et al. Endometrial cysts: diagnosis with MR imaging. Radiology 1991;180(1):73–8. | |

Siegelman ES, Oliver ER. MR Imaging of Endometriosis: Ten Imaging Pearls. RadioGraphics 2012;32(6):1675–91. | |

Coutinho A, Jr, Bittencourt LK, Pires CE, et al. MR imaging in deep pelvic endometriosis: a pictorial essay. Radiographics 2011;31(2):549–67. | |

Rousset P, Gregory J, Rousset-Jablonski C, et al. MR diagnosis of diaphragmatic endometriosis. Eur Radiol 2016;26(11):3968–77. | |

Guerriero S, Saba L, Pascual MA, et al. Transvaginal ultrasound vs. magnetic resonance imaging for diagnosing deep infiltrating endometriosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology 2018;51(5):586–95. | |

Fiaschetti V, Crusco S, Meschini A, et al. Deeply infiltrating endometriosis: evaluation of retro-cervical space on MRI after vaginal opacification. Eur J Radiol 2012;81(11):3638–45. | |

Botterill EM, Esler SJ, McIlwaine KT, et al. Endometriosis: Does the menstrual cycle affect magnetic resonance (MR) imaging evaluation? Eur J Radiol 2015;84(11):2071–9. | |

Macario S, Chassang M, Novellas S, et al. The value of pelvic MRI in the diagnosis of posterior cul-de-sac obliteration in cases of deep pelvic endometriosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2012;199(6):1410–5. | |

Gutzeit A, Binkert CA, Koh DM, et al. Evaluation of the anti-peristaltic effect of glucagon and hyoscine on the small bowel: comparison of intravenous and intramuscular drug administration. Eur Radiol 2012;22(6):1186–94. | |

Gratton SM, Choudhry AJ, Vilos GA, et al. Diagnosis of Endometriosis at Laparoscopy: A Validation Study Comparing Surgeon Visualization with Histologic Findings. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2021. | |

Fernando S, Soh PQ, Cooper M, et al. Reliability of visual diagnosis of endometriosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2013;20(6):783–9. | |

Wykes CB, Clark TJ, Khan KS. Accuracy of laparoscopy in the diagnosis of endometriosis: a systematic quantitative review. BJOG 2004;111(11):1204–12. | |

Pascoal E WJ, Aas-Eng M, Abrao M, et al. The strengths and limitations of diagnostic tools for endometriosis and relevance in diagnostic test accuracy research. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2022. | |

Goncalves MO, Siufi Neto J, Andres MP, et al. Systematic evaluation of endometriosis by transvaginal ultrasound can accurately replace diagnostic laparoscopy, mainly for deep and ovarian endometriosis. Human Reproduction 2021;36(6):1492–500. | |

Mettler L, Schollmeyer T, Lehmann-Willenbrock E, et al. Accuracy of laparoscopic diagnosis of endometriosis. JSLS 2003;7(1):15–8. | |

Jansen RP, Russell P. Nonpigmented endometriosis: clinical, laparoscopic, and pathologic definition. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1986;155(6):1154–9. | |

Koninckx PR, Ussia A, Adamyan L, et al. Deep endometriosis: definition, diagnosis, and treatment. Fertil Steril 2012;98(3):564–71. | |

Moulder JK, Siedhoff MT, Melvin KL, et al. Risk of appendiceal endometriosis among women with deep-infiltrating endometriosis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2017;139(2):149–54. | |

Korom S, Canyurt H, Missbach A, et al. Catamenial pneumothorax revisited: clinical approach and systematic review of the literature. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2004;128(4):502–8. | |

Vlek SL, Lier MCI, Ankersmit M, et al. Laparoscopic Imaging Techniques in Endometriosis Therapy: A Systematic Review. Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology 2016;23(6):886–92. | |

Pastorfide G, Fong YF. Use of narrowband imaging for the detection of endometriosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2015;22(4):535. | |

Kupker W, Van der Linde H, Loning M, et al. Laparoscopic autofluorescence imaging of endometriosis. Fertility and Sterility 2004;82:S72–S3. | |

Malik E, Berg C, Meyhöfer-Malik A, et al. Fluorescence diagnosis of endometriosis using 5-aminolevulinic acid. Surgical Endoscopy 2000;14(5):452–5. | |

Johnson NP, Hummelshoj L, Adamson GD, et al. World Endometriosis Society consensus on the classification of endometriosis. Human Reproduction 2017;32(2):315–24. | |

American Society for Reproductive M. Revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine classification of endometriosis: 1996. Fertility and Sterility 1997;67(5):817–21. | |

Abrao MS, Andres MP, Miller CE, et al. AAGL 2021 Endometriosis Classification: An Anatomy-based Surgical Complexity Score. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2021;28(11):1941–50.e1. | |

Keckstein J, Saridogan E, Ulrich UA, et al. The #Enzian classification: A comprehensive non-invasive and surgical description system for endometriosis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2021;100(7):1165–75. | |

Adamson GD, Pasta DJ. Endometriosis fertility index: the new, validated endometriosis staging system. Fertil Steril 2010;94(5):1609–15. | |

International working group of AAGL E, ESHRE, WES, et al. Endometriosis classification, staging and reporting systems: a review on the road to a universally accepted endometriosis classification†,‡. Human Reproduction Open 2021;2021(4). | |

Espada M, Leonardi M, Reid S, et al. Regarding "AAGL 2021 Endometriosis Classification: An Anatomy-based Surgical Complexity Score". J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2021. | |

Gidwaney R, Badler RL, Yam BL, et al. Endometriosis of Abdominal and Pelvic Wall Scars: Multimodality Imaging Findings, Pathologic Correlation, and Radiologic Mimics. RadioGraphics 2012;32(7):2031–43. | |

ACOG practice bulletin. Medical management of endometriosis. Number 11, December 1999 (replaces Technical Bulletin Number 184, September 1993). Clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2000;71(2):183–96. | |

Ross WT, Newell JM, Zaino R, et al. Appendiceal Endometriosis: Is Diagnosis Dependent on Pathology Evaluation? A Prospective Cohort Study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2020;27(7):1531–7. | |

Ghigna MR, Mercier O, Mussot S, et al. Thoracic endometriosis: clinicopathologic updates and issues about 18 cases from a tertiary referring center. Ann Diagn Pathol 2015;19(5):320–5. | |

Kawaguchi Y, Hanaoka J, Ohshio Y, et al. Diagnosis of thoracic endometriosis with immunohistochemistry. J Thorac Dis 2018;10(6):3468–72. | |

Haga T, Kumasaka T, Kurihara M, et al. Immunohistochemical analysis of thoracic endometriosis. Pathology International 2013;63(9):429–34. | |

Bedaiwy MA, Falcone T. Laboratory testing for endometriosis. Clin Chim Acta 2004;340(1–2):41–56. | |

Grover S, Koh H, Weideman P, et al. The effect of the menstrual cycle on serum CA 125 levels: a population study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1992;167(5):1379–81. | |

Seki K, Kikuchi Y, Uesato T, et al. Increased serum CA 125 levels during the first trimester of pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1986;65(6):583–5. | |

Moss EL, Hollingworth J, Reynolds TM. The role of CA125 in clinical practice. Journal of Clinical Pathology 2005;58(3):308–12. | |

Leyland N, Casper R, Laberge P, et al. Endometriosis: diagnosis and management. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2010;32(7 Suppl 2):S1–32. | |

Dunselman GA, Vermeulen N, Becker C, et al. ESHRE guideline: management of women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod 2014;29(3):400–12. | |

Practice bulletin no. 114: management of endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol 2010;116(1):223–36. | |

Kuan KKW, Gibson DA, Whitaker LHR, et al. Menstruation Dysregulation and Endometriosis Development. Frontiers in Reproductive Health 2021;3(68). | |

Moustafa S, Burn M, Mamillapalli R, et al. Accurate diagnosis of endometriosis using serum microRNAs. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2020;223(4):557.e1–.e11. | |

Anastasiu CV, Moga MA, Neculau AE, et al. Biomarkers for the Noninvasive Diagnosis of Endometriosis: State of the Art and Future Perspectives. Int J Mol Sci 2020;21(5):1750. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can now automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development credits from FIGO plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering 4 multiple choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter.

Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about FIGO’s Continuing Professional Development awards programme CLICK HERE)