Patient Education and Contraceptive Compliance

Authors

INTRODUCTION

The Problem of Unintended Pregnancies

Definition and Extent of the Problem

US data from the 1995 National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) revealed that 28% of all women of reproductive age had experienced an unintended birth.1 About 20% of these women indicated that the birth had been unwanted, while 80% stated that it was mistimed. Estimates from the 2002 NSFG data cycle factoring in pregnancies that ended in abortion placed the percentage of unintended pregnancies (as opposed to births) as just under 50%, essentially unchanged from the mid 1990s.2 An equal proportion of unintended pregnancies end in abortion (44%) compared with birth (43%).3 A recent analysis found that 48% of unintended pregnancies in 2001 (approximately 1.5 million pregnancies) occurred during a month of reported contraception use as opposed to 51% in 1994.2 Despite this small improvement, the fact that nearly half of the unintended pregnancies occurred in women using a contraceptive method demonstrates that all methods of contraception can fail to prevent pregnancy.

Contraceptive Efficacy

Contraceptive efficacy can be calculated from population-based surveys, such as the NSFG or from clinical trials and investigations. In general, failure rates derived from population-based surveys are higher than those from clinical trials, in part because women who participate in clinical trials are likely to be different from those who do not, and may be more motivated or have incentives to use a given method correctly.4 A precise definition of contraceptive effectiveness is the proportional reduction in the monthly probability of conception, a value which is neither observable nor accurately estimated.4 Thus contraceptive efficacy is usually assessed by measuring the number of pregnancies that occur during a specified interval of exposure to a given contraceptive method, and is reported using either the Pearl index or life table techniques. The Pearl index is widely used, and is required by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for approval of a new method of contraception. It is defined as the number of pregnancies per 100 woman-years of exposure. Because failure rates for most methods of contraception decline over time as women gain experience in using the method, or those most likely to have a failure get pregnant sooner, the life table analysis calculates a separate failure rate for each month of use. When failure rates using the life-table method are reported, twelve months is frequently given as a reference period.

Contraceptive effectiveness depends on both the inherent effectiveness of the method itself and correct or perfect usage of the method. The inherent or theoretical efficacy of a method is difficult if not impossible to ascertain, and even perfect use will not result in zero failures. First year failure rates among couples who used a contraceptive method perfectly (both consistently and correctly) have been estimated to range from 0.05 to 26%.5 The failure rates of contraceptive methods during actual use have been shown to be higher than the estimated rates for perfect use.

This failure rate of a method during actual use depends on a number of factors such as age, experience in using the method, and motivation to prevent pregnancy. These factors result in variations in the percentage of users who use a given method incorrectly or inconsistently. Estimates of failure rates in the US among typical married women are included in Table 1, along with the lowest expected failure rates.6 Kost et al in an updated analysis addressed the issue of underreporting of abortions in the National Survey of Family Growth, and have arrived at corrected failure rates by method of contraception, age, marital status, and race.7 These corrected failure rates are much higher than the estimated failure rates for perfect use, and vary widely depending on the characteristics of the user. A woman's age, her union status, her intention towards a future birth and whether or not she had a previous child were the most important determinants of method failure with pill use whereas the relative risk for condom method failure in multivariate analysis for African American women was 1.63 compared with all other ethnicities and for poor women was 1.91 compared with women with income >200% of the poverty level.

A number of authors have commented on the imprecision with which the terms contraceptive efficacy, effectiveness, failure rate, and pregnancy rate are used, and the extent to which characteristics of the user influence the determination of these measures.4, 8, 9 The inherent protection of the method, differences in fecundity by age, frequency of intercourse, and exposure to the risk of pregnancy influence these measures.8 In addition to these factors, the gap between the lowest expected failure rate of a given contraceptive method and the failure rate in typical use is due to differences in the correct and consistent use of the method, or compliance.

Table 1. Percentage of women experiencing an unintended pregnancy during the first year of typical use and the first year of perfect use of contraception and the percentage continuing use at the end of the first year in the United States

| % of Women Experiencing an Unintended Pregnancy within the First Year of Use | % of Women Continuing Use at One Year 3 | ||

|

Method

(1) |

Typical Use 1

(2) |

Perfect Use 2

(3) |

---

(4) |

| No method 4 | 85 | 85 | - |

| Spermicides 5 | 29 | 18 | 42 |

| Withdrawal | 27 | 4 | 43 |

| Fertility awareness-based methods | 25 | - | 51 |

| --------Standard Days method 6> | - | 5 | - |

| --------TwoDay method 6 | - | 4 | - |

| --------Ovulation method 6 | - | 3 | - |

| Sponge | - | - | - |

| --------Parous women | 32 | 20 | 46 |

| --------Nulliparous women | 16 | 9 | 57 |

| Diaphragm 7 | 16 | 6 | 57 |

| Condom 8 | - | - | - |

| --------Female (Reality) | 21 | 5 | 49 |

| --------Male | 15 | 2 | 53 |

| Combined pill and progestin-only pill | 8 | 0.3 | 68 |

| Evra Patch | 8 | 0.3 | 68 |

| NuvaRing | 8 | 0.3 | 68 |

| Depo-Provera | 3 | 0.3 | 56 |

| IUD | - | - | - |

| --------ParaGard (copper T) | 0.8 | 0.6 | 78 |

| --------Mirena (LNG-IUS) | 0.2 | 0.2 | 80 |

| Implanon | 0.05 | 0.05 | 84 |

| Female Sterilization | 0.5 | 0.5 | 100 |

| Male Sterilization | 0.15 | 0.10 | 100 |

Emergency Contraceptive Pills: Treatment initiated within 72 hours after unprotected intercourse reduces the risk of pregnancy by at least 75%. 9

Lactational Amenorrhea Method: LAM is a highly effective, temporary method of contraception. 10

(Hatcher R et al. Contraceptive Technology. 19th ed. 2008: Physician's Desk Reference, 24-25.)

1 Among typical couples who initiate use of a method (not necessarily for the first time), the percentage who experience an accidental pregnancy during the first year if they do not stop use for any other reason. Estimates of the probability of pregnancy during the first year of typical use for spermicides, withdrawal, periodic abstinence, the diaphragm, the male condom, the pill, and Depo-Provera are taken from the 1995 National Survey of Family Growth corrected for underreporting of abortion; see the text for the derivation of estimates for the other methods.

2 Among couples who initiate use of a method (not necessarily for the first time) and who use it perfectly (both consistently and correctly), the percentage who experience an accidental pregnancy during the first year if they do not stop use for any other reason. See the text for the derivation of the estimate for each method.

3 Among couples attempting to avoid pregnancy, the percentage who continue to use a method for 1 year.

4 The percentages becoming pregnant in columns (2) and (3) are based on data from populations where contraception is not used and from women who cease using contraception in order to become pregnant. Among such populations, about 89% become pregnant within 1 year. This estimate was lowered slightly (to 85%) to represent the percentage who would become pregnant within 1 year among women now relying on reversible methods of contraception if they abandoned contraception altogether.

5 Foams, creams, gels, vaginal suppositories, and vaginal film.

6 The Ovulation and TwoDay methods are based on evaluation of cervical mucus. The Standard Days method avoids intercourse on cycle days 8 through 19.

7 With spermicidal cream or jelly.

8 Without spermicides.

9 The treatment schedule is one dose within 120 hours after unprotected intercourse, and a second dose 12 hours after the first dose. Both doses of Plan B can be taken at the same time. Plan B (1 dose is 1 white pill) is the only dedicated product specifically marketed for emergency contraception. The Food and Drug Administration has in addition declared the following 22 brands of oral contraceptives to be safe and effective for emergency contraception: Ogestrel or Ovral (1 dose is 2 white pills), Levlen or Nordette (1 dose is 4 light-orange pills), Cryselle, Levora, Low-Ogestrel, Lo/Ovral or Quasence (1 dose is 4 white pills), Tri-Levlen or Triphasil (1 dose is 4 yellow pills), Jolessa, Portia, Seasonale or Trivora (1 dose is 4 pink pills), Seasonique (1 dose is 4 light-blue-green pills), Empresse (1 dose is 4 orange pills), Alesse, Lessina or Levlite (1 dose is 5 pink pills), Aviane (1 dose is 5 orange pills), and Lutera (1 dose is 5 white pills).

10 However, to maintain effective protection against pregnancy, another method of contraception must be used as soon as menstruation resumes, the frequency or duration of breastfeeds is reduced, bottle feeds are introduced, or the baby reaches 6 months of age.

A number of authors have commented on the imprecision with which the terms contraceptive efficacy, effectiveness, failure rate, and pregnancy rate are used and the extent to which characteristics of the user influence the determination of these measures.4, 8, 9 The inherent level of protection of the method, differences in fecundity by age, frequency of intercourse, and exposure to the risk of pregnancy influence these measures.8 In addition to these factors, the gap between the lowest expected failure rate of a given contraceptive method and the failure rate in typical use is due to differences in the correct and consistent use of the method (i.e. compliance).

Compliance

Definition

Compliance has been defined as "the extent to which a person's behavior ... coincides with medical or health advice".10 Compliance in contraception refers to "the use of a contraceptive method in an ongoing and consistent manner for the prevention of pregnancy".11 Thus both continuation and correct use are required. Although some have argued that the term compliance has paternalistic and pejorative connotations, it is widely used in contraception literature. The terms adherence, correct or consistent use, and successful use have been suggested, although they have not yet been widely adopted.

Compliance has been studied in a number of different medical settings, and although there are important differences between complying with a 10 day prescription of antibiotics and the use of oral contraceptives on a daily basis over a number of years to prevent a pregnancy, rates of compliance with contraception differ little from rates of compliance with other medical treatments.12 With the antibiotic regimen, compliance is enhanced by a decrease in symptoms; with oral contraceptives, pregnancy is avoided, although this does not provide the same ongoing reinforcement for compliance. The treatment of symptoms is generally an unequivocally positive result, while the decision to avoid pregnancy can be associated with ambivalence. The prescription of an antibiotic by a physician involves little choice from the patient, while there are a number of patient-chosen options for contraception. The antibiotic regimen is time-limited, while the use of oral contraceptives is ongoing. Finally, contraceptive decisions involve the complex interactions between sexual partners in a social milieu. For all of these reasons, the study of compliance with contraceptive regimens is complex compared with the study of compliance with other medical regimens.13 However, Cramer has concluded that the study of medical disorders has shown that “no consequence is so severe that all patients can be assumed to comply with the prescribed treatment plan”.12

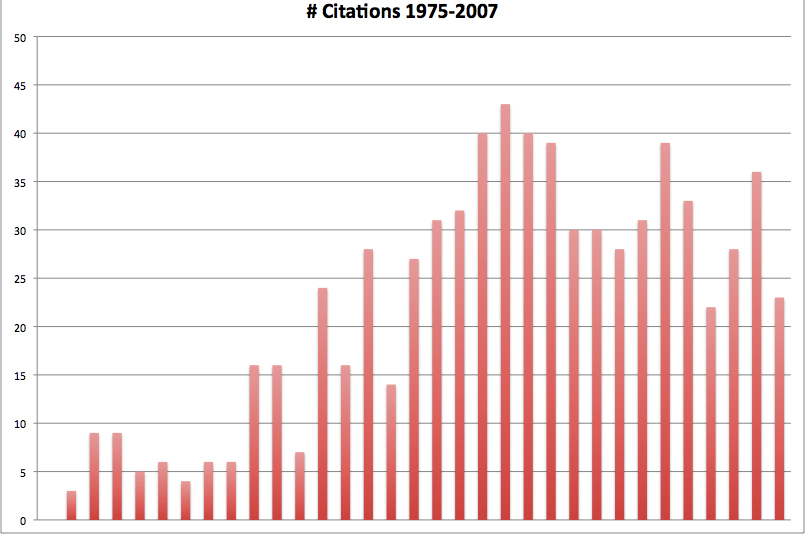

The issue of contraceptive compliance has received increasing attention and focus in the medical literature. The term, concepts of compliance, and practical problems which contribute to less successful contraception are now familiar to most clinicians. A search of the medical literature using the search terms ‘contraception’ and ‘compliance’ revealed only a handful of references prior to 1975; in the mid 1990s there was a marked increase in the number of citations, and a plateau in citations has occurred since that time (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Contraception and compliance

Fig. 1. Contraception and compliance

Continuation

Early research on contraceptive compliance focused on continuation, rather than correct usage.14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19Discontinuation of a method of contraception may be followed by continued sexual activity and the choice of an alternative method of contraception (either reversible or permanent); continued sexual activity and the choice not to use a method of birth control; the decision to be celibate; or the choice of sexual activity which does not entail a risk of pregnancy.

Women who discontinue one method of contraception and who continue to be sexually active while wishing to avoid pregnancy must be encouraged to use another method immediately without any gap in protection. The most effective method for an individual woman is one that she has chosen to use consistently and that suits her individual needs. Pratt and Bachrach noted that 8% of women who discontinued oral contraceptive use did not adopt any method of contraception, continued to be sexually active, and were not seeking pregnancy.20 In a study of contraceptive use patterns, Frost found that only 37% used the same method of contraception over the course of a year; 20% switched methods; 20% had a gap in contraceptive use but were not at risk of unintended pregnancy; 15% had a gap in contraceptive use while remaining at risk of pregnancy.21 Life events accounted for over 50% of the reasons for a gap in use, including beginning or ending a relationship, moving to a new home or community, stopping or starting a job, and having a personal crisis.

Nearly half of unintended pregnancies have been noted to end in induced abortion.22 It has been estimated that as many as 70% of all abortions could be averted if all women at risk for unintended pregnancy used the most effective methods of contraception.23 Up to 75% of abortion patients report that they have been practicing contraception during the month in which they conceived, representing individuals who experienced a contraceptive failure due to user or method factors.24, 25, 26 Nearly half of the prior users had discontinued a method of contraception within three months prior to conception, representing the individuals who were caught in the gap between contraceptive methods.22 Thus, induced abortion is a significant outcome of many unintended pregnancies that result from problems with contraceptive compliance.

Data from the 1995 National Survey of Family Growth have been analyzed to address the issue of contraceptive discontinuation.27 Over one third of women discontinued using a reversible method of contraception for method related reasons in the first year of its use. Discontinuation rates ranged from 16% for the implant to 64% for women using the contraceptive sponge. Thirty-two percent stopped using oral contraceptives, 47% discontinued use of condoms, 43% discontinued using a diaphragm, and 36% requested IUD removal. Although some women switched from one method of contraception to another method, about one third continued to be at risk for an unintended pregnancy in the month after discontinuation because they did not use another method of birth control. Though this number decreases with longer duration after discontinuation of the original method, nearly 20% of women at risk for unintended pregnancy are still not using another method of contraception one year after method discontinuation.27

Discontinuation rates vary, depending on characteristics of the populations studied. Trussell and associates (Table 1) listed the percentage of women estimated to be continuing to use a given method of contraception at the end of one year.5 Two alternative assumptions could be made: that no one becomes pregnant, or that the percentage of women who continue to use the method excludes the women who experienced an accidental pregnancy in the course of the year. Adolescents who begin using a method of contraception are more likely than older women to discontinue its use. The problems of compliance with contraception in adolescents have been widely addressed in the literature.2829 Although reported rates of continuation of oral contraceptive pills vary, studies have found that as few as 12% of adolescents are still using the pill at the end of a year in one study.30

Factors that have been associated with contraceptive compliance in adolescents include a number of social, developmental, and behavioral variables.31 These variables include the perceived risk of pregnancy, frequency of intercourse, degree of intimacy with a sexual partner, acknowledgment of sexuality, feelings of ambivalence about sexual behavior, religious commitment, emotional and sexual maturity, support by significant others, and experience with contraception.11, 32 Health beliefs about contraceptive methods also relate to both the intention to contracept and the actual use of contraception.33 Some adolescents who fail to return for follow-up appointments for contraception are not sexually active, and thus feel that they do not need on-going contraception. However, the pattern of adolescent sexual activity tends to be serial monogamy. The individual adolescent who is not currently sexually active may resume the activity in a new relationship. She may or may not use contraception effectively with a new partner.

Issues related to contraceptive discontinuation of women beyond the age of adolescence have not been addressed as thoroughly as they have been in adolescents. Why do older women discontinue using a given method of contraception? The answer is complex, but there are a number of psychological factors that relate to satisfaction with the method. Miller has stated that "a woman's contraceptive vigilance ... frequently depends upon ... the internal balance between her positive and negative feelings toward getting pregnant and between her positive and negative feelings about her current contraceptive method."34

In addition to psychological traits and attitudes, a variety of other factors affect contraceptive use and compliance. Demographic variables such as age, education, religion, socioeconomic status, marital status, and number of children impact the effective use of contraception. Older, better-educated women of higher socio-economic status and income have been shown in some studies to have fewer accidental pregnancies. The motivation to use contraception effectively varies, depending on the intent of contraception: to postpone pregnancy, to space births, or to avoid pregnancy.35

Factors related to the specific method of contraception may impact compliance. Methods which are coitally related may be perceived as inconvenient or a barrier to spontaneity, and may thus be used less effectively. Cultural factors play a part; in some societies, injections are viewed as powerful and effective medicines that may make compliance more acceptable with this mode of administration.

The experience of side effects is the primary reason that many women give for discontinuing a method of contraception, particularly the most popular reversible method of oral contraception.28, 36, 37, 38 While some of the studies addressing this issue of side effects were performed at a time when the oral contraceptive pill formulations contained higher doses of steroid hormones and were thus more likely to be associated with side effects, the experience of side effects or even the fear of side effects remain important factors in contraceptive discontinuation. Continuation rates have been shown to be better with 35 microgram estrogen-containing pills than with 50 microgram pills.39

Correct Use

It has been stated that the "accurate measurement of compliance is not easy; easy measurements of compliance are not accurate." (Sackett, D. quoted by Haynes.)10 Methods of measuring compliance include direct methods that involve biological assays of serum, urine, or saliva for the level of the prescribed drug or the presence of a marker substance. These methods have been used with oral contraceptives on a very limited basis, and are expensive and time consuming for larger populations.

Indirect methods of measuring compliance include physician estimates, self-reports or diaries, or measurements of outcome—in the case of contraceptives, the measurement of contraceptive failure—pregnancy.40 Many studies of contraceptive compliance have relied on patient self-reporting, although issues surrounding sexuality, privacy, or the personal choice of pregnancy termination may make it more problematic for an individual to admit to less than perfect use of a contraceptive method or to admit to an unintended pregnancy. Innovative ways to record oral contraceptive pill use electronically have been studied,41 and may have future practical uses, such as triggering a reminder alarm. Measurements of outcome—pregnancy rates—are an inaccurate reflection of compliance, as not all noncompliance results in pregnancy. Pregnancy does, however, represent one measure—the ‘bottom line’—of contraceptive compliance.

COMPLIANCE WITH SPECIFIC METHODS OF CONTRACEPTION

Oral Contraceptives

Currently, the most widely used method of reversible contraception in the US is the oral contraceptive pill, used by almost a third of American couples who are using a method of contraception.42 Worldwide, more than 60 million women are users of oral contraceptives.43

Continued Use

A number of studies have cited the experience of side effects as a primary reason for oral contraceptive discontinuation or method switching.21, 28, 38, 44 In the past, physicians' concerns about the side effects of oral contraceptives centered on the risks of medically serious events such as myocardial infarction, stroke, or hypertension. Side effects that could be bothersome or worrisome to patients, such as nausea or breakthrough bleeding were given less attention then were the more serious risks.

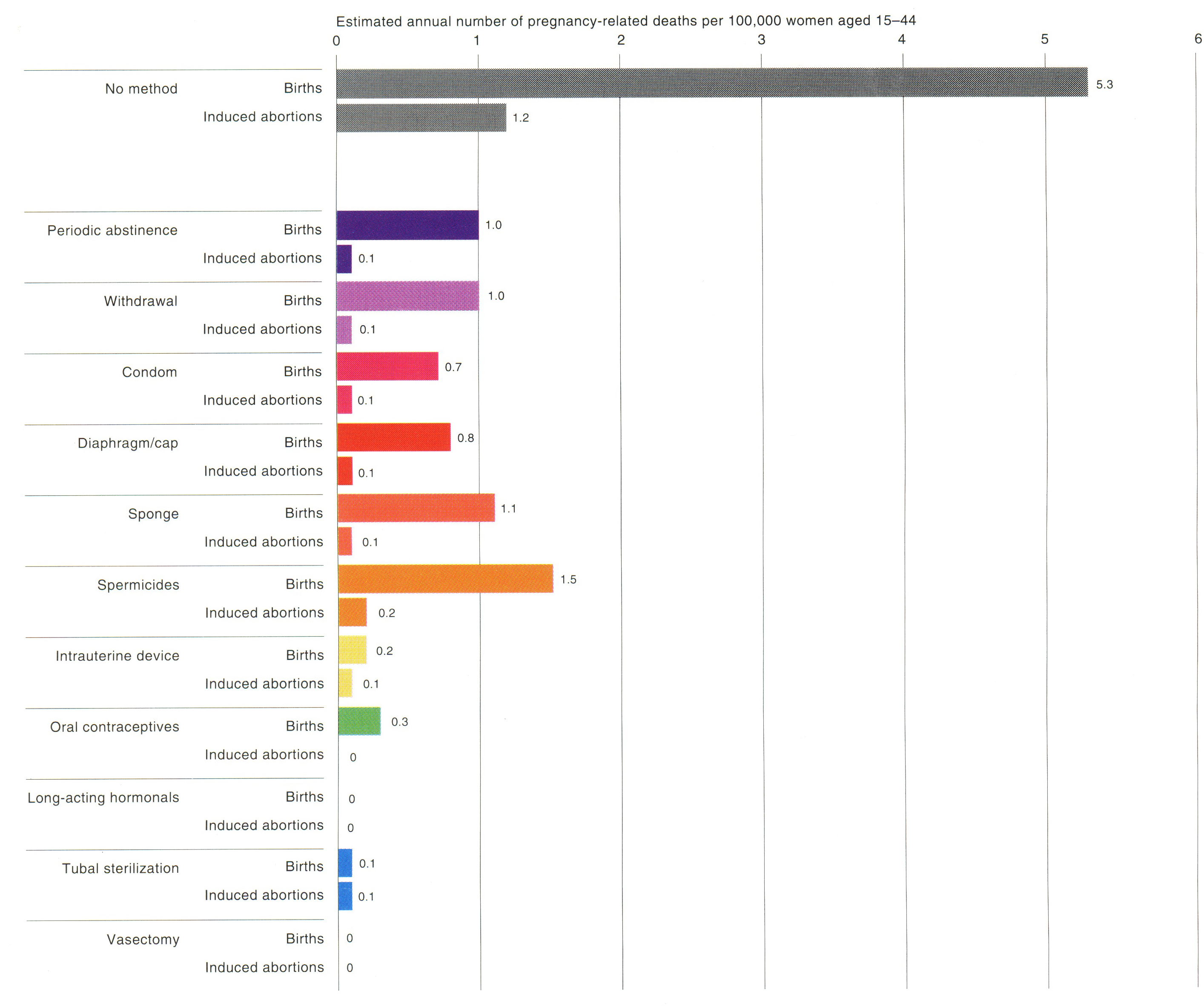

The terms ‘major’ and ‘minor’ side effects illustrates the conceptual framework that was operative in the early years of oral contraceptive use. Oral contraceptive pill formulations have changed over thirty years of pill use, from higher dose estrogen and progestin-containing pills to lower dose pills; today's oral contraceptive pills are thus not the same pills as were used in years past. In addition, the data about the risks of serious medical complications such as myocardial infarction have been analyzed to demonstrate that smoking is the primary risk factor for cardiovascular events (see Fig. 2).45, 46, 47, 48, 49

Fig. 2. Risks of pregnancy-related death versus risk of death for various contraceptives. (Harlap S; Kost K; Forrest JD. Preventing pregnancy, protecting health: a new look at birth control choices in the United States. New York, New York, Alan Guttmacher Institute, 1991.)

While the risks of myocardial infarction in pill users are thought to be primarily due to the effects of smoking, the issue of venous thromboembolism in oral contraceptive users has been raised. In 1995, the United Kingdom’s Committee on the Safety of Medicines recommended that women should use oral contraceptives containing desogestrel or gestodene only if they were prepared to accept an increased risk of thromboembolism. This action was based on observational studies that indicated a 2–3-fold increase in the risk of thromboembolism with pills containing these compounds (so-called 3rd generation pills) when compared to products with levonorgestrel.50 The fact that these studies point in the same direction is concerning, but a number of authors have commented on the likelihood of unrecognized biases.51 Subsequent studies and reanalyses of the data have suggested that a somewhat increased risk may occur for these pills compared with other oral contraceptive pill formulations, although the relative risk is still substantially less than the risk of venous thromboembolism associated with pregnancy, and the absolute magnitude of the risk is small.52, 53 The initial and subsequent reports and the associated publicity led to a major ‘pill scare’ epidemic in the UK and Europe where government bodies reacted with a variety of warnings about the risks of the pill.54 Many women stopped taking their pills because of this scare. An increase in the number of abortions was documented in Norway where sales of oral contraceptives dropped by 17% after the report, and a significant 36% increase in abortions occurred during the first quarter of 1996.55 This is a clear illustration of the adverse effects of media and a scare about possible medical effects of oral contraceptives.

Other than this brief focus on medically serious potential side effects of the pill, the emphasis on side effects and complications of oral contraceptive use has primarily shifted to a focus on the so-called ‘minor’ side effects. Do these minor side effects matter? Drug companies have begun to shift to oral contraceptive formulations with lower doses of both estrogen and progestins with the premise that ‘lower is better’. The World Health Organization (WHO) has concluded that the goals of contraceptive research is to achieve the lowest dose possible that will: maximize contraceptive efficacy and menstrual regularity, minimize the incidence and severity of side effects, and maintain associated noncontraceptive health benefits.56 It has been widely suggested and seems intuitively obvious that a lower hormonal dose of estrogen will result in fewer estrogen-mediated side effects, such as nausea, breast tenderness, and fluid retention. Although comparative data are lacking, there are a number of reports documenting a low incidence of these side effects among users of the newest 20 ug pills.57, 58, 59 However, Goldzieher has emphasized that there are large inter- and intra-population differences in metabolism of both ethinyl estradiol and the progestin components of combination oral contraceptives, suggesting that dose alone may not explain either the contraceptive efficacy or likelihood of side effects in a given individual.60

Clearly, side effects affect satisfaction with the method of contraception and continued use.36 Satisfaction with the clinician who prescribes the pill, and the absence of side effects have been associated with pill continuation and compliance.36 The woman who is dissatisfied with oral contraceptives for whatever reason may decide to discontinue using the method without consulting her physician. One study concluded that explicit medical advice played a less critical role in pill discontinuation than did a woman's own judgment.20

What types of nuisance side effects contribute to problems with ongoing use of oral contraceptives? Irregular bleeding or lack of withdrawal bleeding, nausea, weight gain, breast tenderness, headache, acne, mood changes such as PMS or depression, and skin changes such as chloasma have all been cited as nuisance side effects.6 Some authors question the cause-and-effect relationship with oral contraceptives, as symptoms such as headaches and depression have a high background rate in the population, and baseline rates of these symptoms are often not reported.61, 62 While some studies have not shown that headaches occur more frequently among oral contraceptive pill users than among controls, others have found that headaches, especially migraines were more likely to occur among women using oral contraceptives containing estrogen.63, 64, 65, 66 Combination oral contraceptive use in women who have migraines with aura has been associated with an increased risk of stroke, and thus use of combination oral contraceptives in women who have migraines with aura represents an “unacceptable health risk” (category 4 in the WHO Medical Eligibility Criteria).67

Side effects were more common with high dose oral contraceptives that were available in the past than they are with today's low-dose pill formulations. Data about the frequency of these nuisance effects are difficult to interpret, and studies reporting on their frequency should be reviewed carefully to assess the specific definition of problems such as irregular bleeding. Side effects have been shown to be the primary factor predicting early pill discontinuation. Multiple side effects substantially increase the likelihood of discontinuation; in one study, a single side effect increased the risk by 50%, two by 220%, and three by 320%.37

Methodological problems abound in studies reporting rates of breakthrough bleeding with various oral contraceptive pill formulations.68, 69, 70, 71, 72 Smoking increases the risk of breakthrough bleeding.73 Double-blind crossover studies comparing the incidence of nuisance side effects among the low dose pills are not available. The incidence of breakthrough bleeding or spotting appears to be highest in the first few months of use. The progestin component of the pill may influence the rate of breakthrough bleeding.

The potential consequences of abnormal bleeding to an individual patient may be considerable, although there are variations among cultures in the interpretation of the meaning of abnormal bleeding. Women who have irregular bleeding or spotting may become confused about the timing of their ‘real’ menstrual period, and thus be unsure about when to start a new package of pills. The experience of irregular bleeding may lead to dissatisfaction and pill discontinuation, even within the first few months of use, particularly if the patient has not been counseled that irregular bleeding may resolve over time with consistent use. Women may lose confidence in a method of contraception that creates nuisance effects such as unpredictable bleeding. A woman may lose confidence in her physician who does not appreciate the impact of irregular bleeding or who fails to warn her of the possibility.74 Irregular bleeding can create anxiety among women who fear that oral contraceptives cause cancer, a belief held by 31% of women surveyed in an ACOG Gallup poll.75 The increased anxiety may translate into additional telephone calls or office visits for reassurance with a resultant cost of time and health care dollars. In addition, it has been estimated that over one million unintended pregnancies occur each year in the US because of the discontinuation or misuse of the pill.76

Lack of withdrawal bleeding is another cycle control problem which may be even more anxiety-provoking for women than is breakthrough bleeding, primarily because of the concern about a possible pregnancy. Studies have shown an incidence of lack of withdrawal bleeding of 2–6%.68 The beliefs about lack of withdrawal bleeding have been noted to include the concern that it ‘always means pregnancy’ among 10%, the concern that it was ‘harmful’ in an additional 33%, and the decision not to restart oral contraceptives in 39%.77

In addition, there is a complex inter-relationship between side effects, pill continuation, and correct pill use.21, 28, 38, 78, 79 Missed pills have been associated with, but do not invariably result in, the side effect of breakthrough bleeding. The experience of breakthrough bleeding, whether because of missed pills or not, may lead to dissatisfaction and pill discontinuation. However, the experience of missed pills without breakthrough bleeding or pill failure (pregnancy) may inadvertently reinforce the idea that missed pills are not a problem and thus lead to more missed pills. The experience of nausea or vomiting may result in missed or incompletely absorbed pills, which may result in breakthrough bleeding.

Correct Use

Although data have been cited about oral contraceptive continuation, less is known about the actual usage patterns of the method.80 Recent studies have addressed this issue in some detail, and questions about oral contraceptive pill compliance and missed pills were added to the 1995 NSFG cycle survey.1 In addition to questions of how oral contraceptive usage can best be measured, other questions have been raised which have not been addressed through careful study:

- why do women miss pills?

- what are the demographic characteristics of women who are more likely to miss taking pills?

- what are the characteristics of women who are perfect pill users?

- are some women at greater risk for contraceptive failure because of biological factors related to steroid hormone metabolism?

- which women effectively use a backup method of contraception?

It is apparent from an examination of the gap between the perfect use pregnancy rates of oral contraceptives (0.3%) and the failure rates in typical users (8%) that incorrect or imperfect use is a major contributor to the failure rate.5 When oral contraceptives are initially prescribed for a woman, she can make the decision not to have her prescription filled or not to begin taking the pill. The extent to which this type of noncompliance is a problem with oral contraceptives is not well established. One US study has examined the microbehaviors of oral contraceptive pill use, and noted that 4% of the women who were described as ‘pill acceptors’ did not take the pills at all during the study interval.81

Forgetting to take pills is probably the most common type of error in oral contraceptive pill use, although clinicians have also observed the many ways that pills can be taken incorrectly. One study from Glasgow reported that only 28% of patients were taking the pill perfectly, and 27% reported having missed at least one pill in the previous three months.77 A report from South Africa noted that about one third of the adolescents studied had missed at least one pill in the previous three months, a percentage which was similar to that noted in Glasgow.82 Another small study from the United Kingdom reported that 46% had missed a pill during the previous three months.83 One study of women in Bangladesh included home visits and pill counts, and found that the women had over- or under-taken an average of eight pills per month, with 87% missing at least one or more per cycle.84

Data from the United States are sparse, but the previously noted study of microbehaviors found that only 42% of the women took their pill every day.85 The same study found that 16% of women reported having a pill or pills remaining at the end of the pill packet or cycle. One clinical trial examining side effects and the use of a new pill formulation noted that about 15–25% of women reported missing at least one pill per cycle.86 These subjects were college students who were personally motivated to prevent pregnancy, and who had the extra encouragement and motivation provided by the study coordinators and nurses to comply with pill taking behaviors. One would anticipate that different populations might be less motivated to take their oral contraceptive pills perfectly. One interesting study involved a comparison between self-reported missed pills and data from an electronic device measuring compliance.41 In three months of pill use, the self-report and the electronic report frequently did not agree, and as expected the proportion of women who missed at least three pills according to the electronic data was triple that of the self-report. Fifty to sixty percent of women reported no missed pills, whereas the electronic data indicated that no pills were missed only 20–30% of the time, with the percentage of women missing no pills declining from the first to the third cycle.41 In addition, the electronic data indicated that 30% missed three or more pills in the first cycle, and by the third cycle, this had increased to 50%. Not surprisingly, self-reported data from the NSFG indicated a lower percentage of women missing pills: 13% of all women reported missing two or more pills over three months, and 16% reported missing only one pill over that interval.1 However, of note, about 15% of pill users also use another method of contraception, which may provide some ‘back-up’ contraception.87 Characteristics of women who are more likely to use the pill inconsistently include Hispanic and non-Hispanic black women, those who have recently begun use, and those who have had a previous unintended pregnancy.87

In another report of the women using the electronic devices, 52% of women never missed a pill over the three months of the prospective study, and an additional 21% used a back-up method; the remaining 27% were likely to be at increased risk for pill failure.88

What do we really know about the consequences of missing a pill periodically? Patients may assume that missing a pill mid cycle would be more likely to result in ovulation. However, it appears that the likelihood of follicular development and thus theoretically, the likelihood of ovulation and pregnancy, may be enhanced with a prolongation of the pill-free interval (or placebo interval) of seven days in the typical pill packet.89 This could occur if a woman missed taking a pill or pills at the end of the cycle, or did not restart her new packet of pills correctly, as might occur if she neglected to refill her prescription.90, 91 Studies addressing this question have included only small numbers, but the link with ovulation and pregnancy as an outcome has not been shown.92 In studies in which the pill-free interval was extended to between eight and 14 days, follicular development and the occurrence of ovulation varied widely. In five studies with an extended interval between eight days and 11 days, no ovulations occurred during 208 cycles, as determined through serum hormone measurements and/or ovarian ultrasound.90, 93, 94, 95, 96 However, in other studies (total n = 84 cycles), there were 11 presumed ovulations: one ovulation with an 8-day pill-free interval (total n = 9 cycles),97 two ovulations with a 9-day pill-free interval (total n = 35 cycles),98 two ovulations with a 10-day pill-free interval (total n = 20 cycles),99 and six ovulations with a 14-day pill-free interval (total n = 20 cycles).96 Importantly, there was a great deal of variation between individuals in these studies. It is theoretically possible that some women are particularly sensitive to the lack of suppressive doses of contraceptive steroids that occurs during the pill free interval, and thus might be at increased risk of pregnancy with missed pills, although this has not been conclusively demonstrated. Goldzieher, in a review of the pharmacology of contraceptive steroids, noted large variations in serum levels from patient to patient within relatively homogeneous populations as well as differences between populations in different countries.60

Problems with the transition from one pill packet to the next have been noted by Potter.80 In some countries and with some pill packet configurations, patients are instructed to begin taking the first packet of pills on day five of their cycle. This instruction has led to confusion about the duration of a waiting period between pill packets, with some patients believing that they should always start the next pill packet on day five after the onset of withdrawal bleeding. Because there is some variation in the onset of withdrawal bleeding, some women may thus be starting the next cycle as late as 8–10 days after the previous packet. It has been argued that the 28-day pill packets are less likely to be associated with transition problems than are 21-day packets.94

One major component of compliance with oral contraceptive use is an understanding of the correct instructions for starting the pills and for what to do if pills are missed. The instructions for starting the first packet of pills vary by the type of pills (triphasic versus monophasic) and manufacturer. In the past, most pill packets used in the United States were designed with a Sunday-start, while most pill packets in Europe are designed so that the patient takes her first pill on the first day of menses. More recently, some manufacturers have designed pill packs that can be used for either a ‘Sunday’ or an ‘any day’ start. The advantages of the Sunday start packet are related to the familiarity of some US users and providers with this option, as well as the fact that clinicians may find it easier if all of their patients have a consistent pattern of use. One disadvantage of the Sunday start is that a pill user will complete her packet of pills on a weekend, at a time when it may be more difficult to contact the clinic or physician's office to get a refill.100 The first day start has the advantage of reliably suppressing follicular development from the onset of pill taking, obviating the use of a back-up method of contraception. While the use of a back-up method of contraception for a variable interval of time with the first cycle of use has been widely advocated, there are few data to indicate the extent of compliance with this advice.

Currently, many patients receive information about the initiation of pill use and what to do if pills are missed primarily from the patient package insert that must be included with each prescription for oral contraceptives. The US FDA held a meeting of the Advisory Committee on Fertility and Maternal Health Drugs in 1991 that addressed the issue of labeling instructions on the use of oral contraceptives. The patient package insert has been found to contain insufficient and conflicting instructions that are difficult for the average patient to understand, and which may contribute to errors of compliance.101 The FDA advisory committee unanimously recommended to oral contraceptive manufacturers that they develop standardized and simplified instructions for oral contraceptive use. These instructions now include specific information about missed pills and starting days. It is hoped that the provision of sufficient, consistent, and easy to understand information results in improved compliance and thus fewer unintended pregnancies worldwide. In one study, women who did not read or understand the pill packet instructions were more likely to miss two or more pills per cycle.78

Several organizations have developed guidance on missed pills and how to communicate this information to users. A randomized controlled trial was conducted recently to compare three graphic format instructions for missed pills adapted from existing guidance to a text-based version of instructions submitted to the FDA as part of the efforts to revise the patient insert described above.102 Most women were able to correctly describe the steps to be taken if one pill was missed but this level of knowledge dropped considerably in all groups when women were asked what to do when multiple pills were missed. In general, all three graphic formats were viewed more favorably by participants than the text instructions. The two more simplified graphic instructions (based on revised WHO guidance and Essentials of Contraceptive Technology instructions) resulted in better comprehension than the text instruction or a more complicated graphic version (based on older WHO guidance). However, even in the groups with the best comprehension scores, the scores dropped to less than two out of a possible five when asked to describe the steps to take after missing one inactive pill. It is interesting to note that this study was conducted among highly literate women in Jamaica, revealing that all of these instructions may be too complicated even for highly educated women.

Cost and inconvenience of getting pill refills can also impact compliance, and efforts to minimize this barrier may be helpful in improving compliance.103 Frost and colleagues found that 10% of women who reported a gap in contraception when they were at risk of unintended pregnancy cited difficulties paying for a method or lack of time for medical visits to get a method.21 Provider practices, such as limiting prescriptions for oral contraceptives to only a few months at a time or requiring pap smears before refilling contraceptive pill prescriptions, could contribute to these difficulties. The WHO recommends provision of up to a year's supply of pills for women at initial and return visits and does not recommend any routine testing other than an initial blood pressure measurement for healthy women to initiate or continue contraceptive pills.104

Strategies for Encouraging Oral Contraceptive Compliance

Strategies for encouraging oral contraceptive compliance include being accessible to patients who have concerns about or who fear side effects.74, 78 Those fears must be acknowledged and alleviated through the provision of accurate information about oral contraceptives. The potential benefits of pregnancy prevention and lowered risk of medical problems such as PID, anemia, endometrial and ovarian cancer should be noted and the favorable risk/benefit ratio discussed. Knowledge of non-contraceptive benefits of the pill has been associated with lower rates of missed pills.78 Patients should be cautioned about the effects of missed pills. They can be informed that missing a pill may be associated with breakthrough bleeding or spotting, although this is not invariably the case. The risks of escape follicular development associated with missed pills, particularly at the beginning or end of the cycle that would extend the pill-free interval should be noted.89, 94

The fact that nuisance side effects may frequently result in dissatisfaction should be acknowledged to the patient at the onset of pill use, but with the proviso that alternative formulations are an option if the side effect is persistent. The patient should be cautioned not to stop taking the pills without first discussing the perceived problem with the physician.

A thorough program of patient education can allow the patient to be aware of the possibility of side effects. Frequent follow-up visits may also be helpful, particularly with adolescents. Poor compliance and pill dissatisfaction with resultant discontinuation can thus be minimized. The possibility of side effects must be addressed, as no currently available oral contraceptive carries a guarantee of the absence of side effects. Low-dose pill formulations that are associated with a low incidence of nuisance side effects such as breakthrough bleeding, lack of withdrawal bleeding, nausea, headaches, and breast tenderness should be prescribed when possible.

Other non-oral combined contraceptive methods

Two novel combined contraceptive methods were approved for use in the US in 2002: the combined hormonal transdermal patch and the combined hormonal vaginal ring. The contraceptive patch was designed to mimic the 28-day cycle of the oral contraceptive with three consecutive patches each worn for one week followed by a patch-free week.105 The contraceptive vaginal ring also mimics this schedule as it is worn for three consecutive weeks followed by removal of the ring for one week.106 The contraceptive efficacy of both methods has been found to be similar to that of the combined oral contraceptive but compliance with treatment has been shown to be improved with these novel delivery systems due to their once-weekly or once-monthly schedules and improved side effect profiles.106, 107, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112, 113

Barrier Methods of Contraception

The failure rates with various barrier methods of contraception including spermicides relate, at least in part, to lack of use with each act of intercourse, or to improper use. Recent arguments have been made that the use of two concurrent barrier methods of contraception, when used consistently and perfectly, result in higher efficacy and pregnancy prevention than had been previously suggested, as the assumptions for independence in consistent use are probably not valid.114 Dissatisfaction with barrier methods which results in discontinuation tends to be relatively high; in the national survey data, 30% of married women discontinued use of the diaphragm at the end of a year, 29% discontinued reliance on condoms, and 45% discontinued spermicide use.14

In a study which looked at the components of compliance with the use of condoms, Oakley defined ‘microbehaviors’ of condom use, which included: putting the condom on prior to penetration, holding the condom in place during withdrawal, withdrawing while the penis is still erect, and using a condom during every act of intercourse.115 Data from the 2002 NSFG found that depending on the age group, only 14–28% of women who said they used condoms reported using a condom during every act of intercourse.42

Consumer awareness of condoms has increased markedly since the beginning of the HIV epidemic, and sales/use has also grown markedly.116, 117 Among adolescents, the use of condoms has increased. Data from the NSFG indicate that 27% of adolescents report using condoms as their method of contraception, and condom use was reported by 42% of all women at the time of first intercourse.42 The availability of condoms in school-based clinics has been shown in two studies to result in increased use of condoms without increased rates of sexual activity.118, 119 Recent surveys have begun to focus on the reality that women/couples are using dual methods, including most commonly a hormonal method and condoms. Data from the 2002 NSFG found that 4% of all women using contraception were using the pill and condom.120 This percentage increased with decreasing age so that 14% of all women aged 15–44 using contraception were using both the pill and the condom compared with only 0.5% of women aged 35–44 using this method combination. The percentage use of this method combination was also highest in never married, non-cohabitating women, indicating the likely reliance on condoms for STI/HIV prevention. There is evidence that offering users of oral contraceptives information about a choice of barrier options (spermicidal film vs. condoms) resulted in increased barrier use without decreasing condom use.121 There is, however, a complex interaction surrounding the use of two methods, and in one sample, about one quarter of dual users reported plans to reduce condom use in the future.122 Consumers’ perceptions of condoms have been changed as a result of increased publicity and public comfort in talking about the method.

Recent focus on HIV prevention has led to the increased use of condoms. Given the potential risks and sequelae of HIV and other STDs, it is no longer appropriate for clinicians to discuss only contraception without also addressing STD risk and the use of barrier methods.123 Latex condoms, when used consistently and correctly, are highly effective at reducing the risk for HIV infection and other STDs.124

Compliance with barrier methods of contraception—correct and consistent use—is determined by a complex interaction of characteristics of the specific method, characteristics of the user, and the specific situation.125 Different barrier methods may interfere with sexual spontaneity and enjoyment to varying degrees. Negotiation between the sexual partners about barrier method use is affected by the stage of the sexual relationship, adolescent development, comfort with sexuality and sexual communication, other characteristics of the relationship such as mutuality or collaboration, and whether there are elements of unequal relationships, coercion, force, or abuse.126 Previous contraceptive use and familiarity with the method are also factors.125

Although most barrier methods can be obtained without a prescription from a provider, clinicians still have an extremely important role in promoting effective and consistent method use. The quality of the evidence that latex condoms are effective in reducing the risk of HIV transmission is good, while the evidence for other barrier methods is less firmly established.

There is still an urgent need for the development of better barrier methods which meet consumers’ needs and which are effective in both pregnancy prevention and reducing the risk of STD acquisition.

Contraceptive Methods that are Less Compliance-Dependent

IUD

Certain methods of contraception are less dependent on the user for effectiveness than others. In recent years, there has been increasing focus and attention on these methods, as compliance has been recognized as an issue in contraceptive effectiveness. The IUD, injectable methods, and implantable methods do not require ongoing motivation to the same extent as do coitally related methods or oral contraceptives.

The intrauterine device, IUD, is used widely in China and Europe, although use in the United States is low.120, 127 NSFG data from 2002 indicate use by less than 1% of US women.120 However, the introduction of the levonorgestrel IUD in the US in 2000 may be increasing the use in the US due its non-contraceptive benefits of decreased menstrual bleeding and potential treatment of heavy bleeding, endometriosis, and adenomyosis.

The IUD is a model for a contraceptive method that requires little ongoing user compliance. IUD users in clinical trials are typically examined more frequently by a clinician than are typical users. Thus, expulsions would be noted more consistently, resulting in somewhat lower failure rates than among typical users. However, the gap between the lowest reported failure rates and the failure rates among typical users is smaller than with other methods such as oral contraceptives. The failure rates of today’s IUDs are comparable to that of sterilization procedures.127

Depot Medroxyprogesterone Acetate

One long-acting injectable progestin, available as depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA), was approved for contraceptive use in the United States in 1992, and has been shown to be highly effective. The most commonly used regimen involves an injection every three months, and is touted as ‘the birth control you only have to think about four times a year’. Compliance with an every three months regimen may have its own difficulties, and the early studies of efficacy reported relatively high rates of subjects who were lost to follow-up.128 The percentage of individuals who were lost to follow-up represents one measure of compliance and patient satisfaction. In one recent US study, only 57% of women returned for a second shot; 63% of those who received a second injection returned for their third, with a one-year continuation rate of only 23%.129 More recently, it has been argued that extending the ‘grace period’ of the interval for re-injection from two to four weeks does not increase the risk of pregnancy, and thus that the definition of DMPA continuation could be relaxed.130

The use of DMPA is associated with side effects which include an almost invariable change in menstrual bleeding, mild weight gain, and mood changes.131 As with oral contraceptives, these factors may influence acceptability or continuation. Prior to its approval for general use, DMPA had been used in the United States for individuals with special needs in relationship to contraception, such as drug abusers or women with developmental delay; one of the clear benefits of the method is the relatively infrequent compliance requirements.131 Recent controversies around the impact of DMPA on bone mineral density have led clinicians to be wary of initiating or continuing to prescribe DMPA, particularly for adolescents. The Society for Adolescent Medicine has issued a position statement supporting the need to balance the physical, social and economic cost of adolescent pregnancy versus the immediate and long-term impact of DMPA on bone.132 The benefits of easy compliance are particularly important for adolescents. Recent studies have shown that the bone loss occurring with DMPA is easily reversible, and have provided reassurance that the use of DMPA is not likely to be a risk factor for low bone density and fractures in older women.133, 134

Implants

Contraceptive implants, including levonorgestrel-containing subdermal devices that became available for use in the United States in 1991, are highly effective at preventing pregnancy.135 The six-rod levonorgestrel-containing subdermal implant (Norplant) was removed from the US market in 2000 and replaced by a single rod subdermal implant which releases etonorgestrel (3-ketodesogestrel, Implanon) in 2006 which has been approved for use up to three years. An additional two-rod levonorgestrel implant (Jadelle) is widely used worldwide and approved, though not marketed, in the US. If the user is able to tolerate side effects such as irregular bleeding, the continued use of the subdermal implant containing levonorgestrel requires no ongoing compliance after the initial insertion. Continuation rates with subdermal implants are typically 70–80% or higher.136, 137 User error is not a factor in effectiveness. The fact that the removal of the devices requires a minor surgical procedure helps to encourage continued use, although the coercive potential has been a focus of public and scholarly discussion.138 Discontinuation is thus an active event rather than a passive one of non-use. Side effects such as bleeding irregularities are typically the most common reason given for discontinuation.139, 140, 141 Some patients may benefit from treatment options for irregular bleeding, although the best treatment has not been established, and reviews do not support routine treatment for irregular bleeding.142 Adolescents and adults using implants have been found to have comparable continuation rates and tolerance of side effects.143, 144 Studies comparing Norplant and oral contraceptive use in adolescents found significantly higher continuation rates and thus lower pregnancy rates among Norplant users.145, 146, 147 Similar comparative studies have not been performed with Implanon.

EMERGENCY CONTRACEPTION

It has long been recognized that contraceptive emergencies can occur. A discussion of patient education and compliance would be incomplete without a discussion of this option, which recognizes the problems of compliance with other contraceptive methods and begs for greater public awareness. Hatcher and colleagues, in the classic reference, Contraceptive Technology, have stated:

“As long as condoms break, inclination and opportunity unexpectedly converge, men rape women, diaphragms and cervical caps are dislodged, people are so ambivalent about sex that they need to feel swept away, IUDs are expelled, and pills are lost or forgotten, we will need morning-after birth control. Our birth control technology is imperfect and human behavior is imperfect. Family planners who don’t offer postcoital contraception shortchange their patients.”148

A variety of methods of postcoital contraception, sometimes called the ‘morning-after pill’, ‘emergency contraceptive pills’, or more recently ‘emergency contraception’ (EC), has been studied. The most commonly prescribed method and the only FDA approved emergency contraceptive regimen in the United States is the levonorgestrel-only ‘Plan B’. The levorgestrel-only methods have been found to be more effective and to have fewer side effects than the more traditional Yuzpe regimen.149, 150 The Yuzpe method, however, has the advantage of being a higher dose of combined oral contraceptive pills, which allows for women who are using the combined oral contraceptive pill to easily access this regimen without an additional prescription and provides an emergency contraceptive regimen in low resource settings where levonorgestrel-only pills may not be available.151

Emergency contraception has been called the ‘best-kept contraceptive secret’, and it has also been stated that it is a method about which ‘women know little, and men know less’.152, 153 Recent efforts from ACOG and the AMA have sought to publicize the method’s availability to the public, and to increase knowledge and prescribing among clinicians.154, 155 In a study reported in 1994, few primary care physicians or reproductive healthcare providers had ever discussed emergency contraception with patients or had literature available.156 By 2000, the percentage of physicians including counseling on emergency contraception as part of their routine care increased but still was only about 20%.157 Despite the lack of awareness about emergency contraception, it was estimated in a recent analysis that in 2000 alone, 51,000 abortions were prevented through the use of emergency contraception.22 In August 2006, Plan B became available from pharmacies without a prescription for women 18 and older, but remains available by prescription only for those younger than 18. Many experts have questioned the age restriction on non-prescription status of EC given its known safety profile.158 The American Academy of Pediatrics and the Society for Adolescent Medicine supports over-the-counter access for adolescents without age restrictions.159 A recent study of 2117 women, including 964 adolescents found that nonprescription access and advanced provision of EC did not lead to increases in risky sexual behavior or change the use of routine contraception, including condoms.160 EC is available without a prescription for adolescents in over 40 countries, with direct over-the-counter access in India, Finland, Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden.158

SPECIAL POPULATIONS

Some populations have unique needs in terms of contraception, and special problems related to compliance with contraceptive use. Adolescents may represent the largest such group of special-needs patients. Women at risk for fetal anomalies are another such group, as are women with medical problems that would make pregnancy a high-risk situation.

Adolescents

Adolescents are less likely than are older women to use contraceptive methods consistently and correctly. Relatively few adolescents report the use of any method of contraception at first intercourse, and many delay seeking medical advice for at least six months or more after coitarche.11 Factors which have been cited as affecting compliance in adolescents include: the discrepancy between emotional and sexual development; the reluctance to acknowledge sexual activity to peers or parents, thus precluding reinforcement by these groups; the typical adolescent sense of invulnerability and belief that pregnancy is unlikely (‘It can't happen to me’); the nature of sexual activity, which may be infrequent, unplanned, and unpredictable; the fact that many disadvantaged teens lack goals for the future which provide motivation for postponing sexual activity; a lack of understanding of menstrual physiology and fertility; and previous experience with contraceptives.11

The most popular method of contraception among adolescent young women is oral contraception.161 Condoms are the next most popular method. Misinformation about oral contraceptives is widespread among young women and their mothers. The mothers of today's adolescents may themselves have taken high dose oral contraceptives, and have concerns about the risks of both serious and nuisance side effects which do not apply to the low dose pills which are currently available. In addition, they were often exposed to the negative media influence during the 1970s.162, 163 Providing accurate, current information to adolescents and their mothers (if the daughter has actively involved her mother in the decision-making process) is helpful in dispelling myths that may contribute to fear, dissatisfaction, and discontinuation.

Adolescents have a number of concerns and fears about the nuisance side effects that may occur with oral contraceptive use. Almost invariably, they have heard about the possibility of weight gain, and may be concerned about interaction of the pill with cigarettes, possible fertility problems or even birth defects that they fear may result from oral contraceptive use.15 The experience of side effects, or even the perception of weight gain are associated with lower rates of pill continuation.15 Because one typical pattern of sexual activity during adolescence is serial monogamy, adolescents may adopt an on-again/off-again use of oral contraceptives which may leave them vulnerable to gaps in contraceptive coverage if they discontinue oral contraceptive use when they break up with a boyfriend, but fail to re-establish use when they are once again sexually active in a new relationship. This sporadic use may also contribute to a longer total duration of nuisance side effects which tend to decrease in frequency over time, but which may recur with each new restart of oral contraceptive use.74

Adolescents require on-going reinforcement and encouragement in order to be effective contraceptors. Frequent follow-up visits are important, as is an emphasis on the availability of advice by telephone should questions arise. Adolescents should be specifically counseled not to discontinue their method of contraception without discussing the problem with their clinician.

Women at High Risk for Fetal Anomalies

Although the list of known and well-established teratogens is relatively small, certain drugs such as lithium carbonate or isotretinoin are used among women of childbearing age. Lithium carbonate carries a risk of congenital malformations.164 Isotretinoin, used to treat severe cystic acne, is associated with a rate of fetal anomalies which approaches 25% for pregnancies that proceed beyond 20 weeks.165 The manufacturer of Accutane, together with the US FDA, implemented a multicomponent Pregnancy Prevention Program in 1988. A follow-up of this program found that the pregnancy rate among users of Accutane was substantially lower than that in the general population.166 Nationally and internationally, pregnancies continue to occur among Isotretenoin users and the issue of contraception for these women remains a topic of ongoing concern.167 The choice or recommendation of a method of contraception for these women and for others who are taking medications that may carry some risk of fetal anomalies, must take into consideration the failure rate of the method in typical users and the likelihood of compliance in the individual patient. The problems of poor compliance should be considered, and in the US, a program called iPledge mandates patient, pharmacy, and prescriber registration, pregnancy testing, and the use of two concurrent methods of contraception.168 Previous guidelines from the Teratology Society had suggested the use of a less compliance dependant methods—an injectable or implantable method or sterilization—would be most appropriate.169

Women with Medical Problems

Women with medical problems such as hypertension or diabetes mellitus represent another large group of women for whom pregnancy would entail potential risks to their own health or the health of their fetus. The risk and benefits of effective contraceptive methods must be compared with the risk and benefits of pregnancy (pregnancy termination or birth). Pregnancy entails a risk of morbidity and mortality that is dependant on age, the outcome of pregnancy, and any underlying medical conditions. For women with medical problems who desire pregnancy, timing pregnancy to correspond with a time of disease control or quiescence as much as possible is of the utmost importance and requires effective contraception. The WHO’s publication Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use lists “Conditions that expose a woman to increased risk as a result of unintended pregnancy”.67

Harlap, Kost, and Forrest compared the risks of pregnancy-related death among women using no method of contraception and the risk of death among those using various methods of contraception, considering the failure rates of these methods (Fig. 2).170 They have also compared pregnancy-related mortality among women using no method of contraception and the mortality associated with various methods of contraception, factoring in the effectiveness of each method in preventing pregnancy as well as the potential risks of mortality from the method itself.170 All methods of contraception are safer than using no method and having a birth.

For an individual woman, especially one with chronic medical problems, it is impossible to accurately predict the magnitude of risk of mortality which pregnancy would entail, although the risks associated with pregnancy for various populations give some information which may be useful to decision making. Clearly the more severe the underlying disease, the greater the potential risks associated with pregnancy. The benefits of using a method of contraception that is highly effective may outweigh the potential risks associated with its use, if the consequences of an unintended pregnancy would be severe. For example, a woman with diabetes mellitus who is poorly compliant with her insulin regimen as well as with the use of barrier contraceptives may benefit from a highly effective method of contraception that is less compliance-dependant such as the implantable subdermal levonorgestrel system. For this woman, uncontrolled diabetes is associated with fetal and maternal risks; the potential for an unintended pregnancy is high if barrier methods are not used perfectly, and the benefits of the very effective subdermal system appear to outweigh the potential risks.

The WHO has convened expert scientific group meetings to review the data from clinical and epidemiological research on medical criteria for contraception prescribing and to then recommend medical eligibility criteria for different contraceptive methods.67 Four categories were described for classification, ranging from category 1 (a condition for which there is no restriction for the use of the contraceptive method), to category 4 (a condition that represents an unacceptable health risk if the contraceptive method is used). This represents an attempt to encourage the use of an evidence-based approach developed with the medical judgments and opinions of experts in the field on contraception. This approach supersedes a more traditional approach in which ‘contraindications’ or ‘relative contraindications’ or ‘cautions’ were terms that addressed questions of risk and safety. The Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use is currently in its 3rd edition.67 The 4th edition, set to be completed in 2008, utilizes the same approach for surveillance of new evidence.171

PATIENT EDUCATION

A major premise among clinicians and researchers in the area of contraceptive compliance is that adequate knowledge is not the sole requirement for correct use, but that it is essential.172, 173 Compliance is clearly an essential component of contraceptive efficacy. Efforts aimed at increasing a patient's knowledge and understanding of a prescribed therapy are a necessary first step toward compliance.174 The provision of clear and simple instructions—given both orally and in written form—results in greater information retention in the general medical setting. Forgetting to take pills is probably the most common type of error in oral contraceptive pill use, although clinicians have also observed the many ways that pills can be taken incorrectly.174 Attention to readability of patient education materials is critical in the provision of written materials, as large segments of the US population (approaching 20%) have been noted to be functionally illiterate, i.e. not able to read materials written at a fourth to fifth grade level.175

The clinician-patient interaction is an important component of reproductive counseling, and has been described as the main determinant of the accuracy and completeness of patient data, diagnostic accuracy, efficiency in the encounter, compliance, patient understanding of problems, and both patient and physician satisfaction.176 However, little attention has been given to the teaching or practice of this critical skill. Involvement of the patient herself in decision making is also essential.177 “Motivational Interviewing” (MI), defined as “a directive, client-centered counseling style for eliciting behavior change by helping clients explore and resolve ambivalence”, utilizes this relationship-centered approach.178

History taking should include questions that help to establish a patient's background knowledge and health beliefs about methods of contraception. Frequently, myths and misinformation will surface, which may erode confidence in the method if not dispelled. The clinician can address these specific misperceptions, in an effort to increase the likelihood of compliance. Clinicians can make efforts to become better sources of information to their patients; the use of ancillary health personnel within an office or clinic setting may be of benefit.174 Data suggest that counseling can improve contraceptive use.74, 179, 180, 181, 182 However, the most effective strategies for counseling to prevent unintended pregnancy or improve contraceptive compliance have not been identified.

In a review of the literature, Moos and colleagues found no consistent evidence regarding the effectiveness of counseling in changing knowledge or behaviors or in reducing unintended pregnancies in the US.182 This review noted that most studies in this area are methodologically flawed and/or have very small sample sizes. The authors provided several suggestions for research in this area including: further evaluation of the provider/client dynamic; the role of men in contraceptive decision making; the interaction between the clinical setting and community-based interventions; and more rigorous randomized or non-randomized controlled studies to evaluate counseling interventions.

One recent randomized controlled trial of pregnancy prevention counseling randomized patients to a general health counseling control group versus a group that received counseling using MI.183 Unfortunately, at one year, no differences with regard to maintenance or improvement in effective contraceptive use were found between the groups. Another trial randomized women at risk for having an alcohol-exposed pregnancy to receive information plus a brief motivational intervention, or information alone; the group that received the motivational intervention was more likely to use effective contraception at three, six, and nine months.184 Subsequent studies may support the use of MI as an effective technique in contraception counseling.

Physicians must be sensitive to the fears and concerns about various methods of contraception that the patient may express, as these fears are not always rational or easily dispelled by information alone, and may result in problems with compliance. Data from the ACOG Gallup poll highlight the extent to which misinformation is prevalent among the general public.75

Clinicians should be realistic with patients about the possibility of nuisance side effects, which may impact on method satisfaction and continuation.185 An explanation of types of side effects that may be seen with a given method of contraception, the likely course of the side effects (i.e. that they may decrease over time), and reassurance about their meaning are helpful. The physician may state, "If you have problems with your method of birth control, don't stop using it without discussing it with me, unless you are planning a pregnancy". The problem of a gap in effective contraception that may be associated with method switching can be addressed.

The patient must be informed of the efficacy of each method of contraception, including both estimates of the lowest expected failure rate and the failure rate in typical users. She should be informed that her own efforts in good compliance would result in a failure rate that is lower than the rate in typical users. She should be encouraged to thoughtfully assess her own likelihood of compliance, given past experiences with contraception, and considering her partner's concerns and wishes. Active involvement and support from a partner may benefit compliance. Many women are unaware of the potential noncontraceptive benefits of contraceptive methods, although recent focus on the use of oral contraceptives for the indications of acne and premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) have brought an increased awareness to the public.186 Direct to consumer advertising has focused attention on these benefits.

Some patients realize that they have had considerable difficulty with compliance in the past. The clinician can encourage these women to choose a method of contraception that is less compliance dependent. The results of non-compliance (i.e. the risks of unintended pregnancy) should be pointed out. The clinician, too, should form an opinion of the individual patient's likelihood of compliance with a method of contraception and consider how realistic he or she judges the woman's own assessment to be.174 The physician can review past compliance with antibiotic prescriptions, return appointments, and past unintended pregnancies. While the best compliance will occur with a method that the individual woman has freely chosen, feels comfortable and is satisfied with, and which is easy to use and produces few side effects, compliance is a complicated issue.187 Ambivalent feelings about pregnancy may further complicate compliance.