This chapter should be cited as follows:

Barsoum M, Griffiths J, et al., Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.415803

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Obstetrics Module

Volume 15

The puerperium

Volume Editors:

Dr Kate Lightly, University of Liverpool, UK

Professor Andrew Weeks, University of Liverpool, UK

Chapter

Mental Health in the Puerperium

First published: February 2021

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

INTRODUCTION

Mental health problems are common in the perinatal period (during pregnancy and 1 year post natal). In the UK one in five women will experience a mental health problem in the perinatal period, and suicide is the leading cause of death. There is a substantial cost to society of £8.1 billion in unmet need.1 The average cost to society of one case of perinatal depression is around £74,000, of which £23,000 relates to the mother and £51,000 relates to impacts on the child.1 Prevalence of common mental health disorders in perinatal period were found to be higher in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC).2 One in five women in LMIC were found to experience depression, anxiety or somatic disorders. This was found to be higher in adolescent pregnancies, and 95% of adolescent pregnancies occur in LMIC. In addition to the higher burden, there are also fewer resources and trained staff, and less psychoeducation available.3

Stigma towards mental health is an ongoing issue worldwide. The WHO 10 Facts on mental health states that “misunderstanding and stigma surrounding mental ill health are widespread. Despite the existence of effective treatments for mental disorders, there is a belief that they untreatable or that people with mental disorders are difficult, not intelligent, or incapable of making decisions. This stigma can lead to abuse, rejection and isolation and exclude people from health care or support. Within the health system, people are too often treated in institutions which resemble human warehouses rather than places of healing.”4 Patient care needs to be inclusive of public health, primary care, and physical, maternity and mental health services.

This chapter aims to provide a user friendly guide to common disorders in the puerperium, but also that can extend into the perinatal period. This is aimed to provide advice and guidance on screening, assessment, treatment that can be applicable worldwide. Other chapters within the GLOWM series provide more detailed discussion of postnatal depression and puerperal psychosis.

GENERAL MANAGEMENT PRINCIPLES

If there are any concerns about the mental health of a woman in the puerperium, then it is necessary to take a full psychiatric history. This history will also need to include extra perinatal details to enable a full assessment for both an accurate diagnosis and assessment of risk.

Classically a full psychiatric history includes the following:

- Basic information – name, age, marital status, occupation and legal status;

- Presenting complaint and reason for referral – taken from both the woman and referrer;

- History of presenting complaint – detailed account of the current mental health by individual symptoms;

- Past psychiatric history – including previous self harm – in chronological order;

- Past medical history – including conditions not treated;

- Drug history, use of alcohol and other psychoactive substances such as cannabis, cocaine, khat, LSD, magic mushrooms etc.;

- Family psychiatric history and family history – in particular psychosis, bipolar affective disorder (BPAD), postpartum mental illness;

- Personal history including birth and development, early childhood, adolescence, educational record, occupational record, psychosexual history and forensic history;

- Premorbid personality – how they would describe themselves prior to this episode;

- Social history – current life circumstances;

- Collateral history – can provide useful information on current symptoms, change in recent symptoms and especially if patients are confused or finding it hard to communicate.

In the puerperium there are other important areas to explore, these include:

- Delivery – date, mode and any complications.

- Past postnatal mental health – women may give you a diagnosis, e.g. previous postpartum depression but this needs further clarification and details of exactly what happened need to be known. This will help you identify possible risk factors.

- Obstetric history – ask about previous pregnancies, pregnancy losses both spontaneous and planned, difficulties within pregnancy or during labor, e.g. traumatic deliveries. Ask details about this most recent pregnancy and labor. This will help identify possible triggers for trauma responses.

- Pre-existing mental health conditions will need exploration – a diagnosis alone is not sufficient. A detailed description of past illnesses. Severity of their illness when unwell, the general management of their psychiatric condition and an idea of the recent level of stability of mental health are all important factors to explore.

- Bonding and attachment needs exploration, this includes bonding with current baby both in the antenatal period and after delivery, as well as the history with any other children. The current bond and attachment between mother and baby needs to be assessed by spending some time watching them together.

- When asking about social history it is important to identify the current level of support for the mother, are there any recent changes.

- It is also important to know what other children are at home with the mother; this will help inform the risk assessment as well as add information to the daily pressures she may have.

MENTAL STATE EXAMINATION

This is an essential component of a psychiatric assessment and will need to be documented clearly as it adds to both the differential diagnosis and the risk assessment.

The specific areas of the Mental State Examination are:

- Appearance and behavior – Is clothing appropriate? Are they relaxed, scared or agitated? Any gait abnormalities? Any abnormal movements? What is their facial expression? Do they make eye contact and react to speech?

- Speech – Is the speech coherent and relevant to questions? What is the rate of speech? Is it hard to interrupt speech? Is speech volume appropriate to setting?

- Thought – Form, content and interpretation of events? Do they feel in control of their own thoughts? Do they think people can insert or remove thoughts from their mind? Can they read other peoples thoughts or think their thoughts are being broadcast? Any obsessive thoughts with or without compulsive actions?

- Paranoia – Do they feel they are being watched, monitored or followed? Do they think cameras or monitoring devices are in their residence? Do they feel their or families lives are in immediate danger?

- Mood/affect – subjectively and objectively. Do they feel low or depressed? Do they appear elated with a high mood? Or a mood incongruous with situation?

- Altered perceptions, e.g. hallucinatory experiences can be visual, auditory, tactile, olfactory in nature.

- Cognitive state – Orientation, attention, concentration and memory?

- Insight – Do they know they’re ill, if so do they accept treatment if required.

Risk – Must include the perinatal red flags5 (numbers 1–3 below – which are shown to be a risk of completed suicide):

- New and violent thoughts of suicide;

- Rapid changing of mental state (can vary hour to hour);

- Persistent feelings of disengagement with the baby and being a bad mother;

- New psychotic symptoms – any delusions or hallucination involving the baby/children;

- Thoughts of self-harm or harm towards others;

- Risk of neglect of emotional harm;

- Risk of domestic violence and abuse to mother;

- Substance misuse.

It is important to talk about suicide and speaking about it will not increase a patient’s risk of suicide. The Zero Suicide Alliance6 provides free worldwide online introduction training via the following link: https://www.zerosuicidealliance.com/.

BREAST FEEDING AND MEDICATION

“Infants should be exclusively breastfed for the first six months of life. Thereafter, to meet their evolving nutritional requirements, infants should receive nutritionally adequate and safe complementary foods while breastfeeding continues for up to two years of age or beyond.”7

All psychotropic drugs will be transferred into mothers’ milk; however, this is usually at much lower doses than intrauterine. The relative infant dose is the percentage of the mother's dose that the baby ingests through breast milk; a dose of less than 10% is considered safe.8 The relative infant dose (%) is calculated by dividing the daily infant dose via breastmilk (in mg/kg/day) by the maternal daily dose (mg/kg of body weight/day).9

General advice in treating breastfeeding mothers from British Association of Psychopharmacology guidance includes:10

- As in pregnancy, previous treatment response should guide future treatment choices.

- Advise women against co-sleeping with their babies.

- Take care with any sedating medication especially in the postnatal period, since excessive sedation can hinder baby care and breastfeeding. Although sedation can often resolve over a short period after starting a medication, alternative options may need to be considered.

- Breastfeeding women with mental illness should have rapid access to psychological therapies, but where illness is more severe, drug therapy may be an essential component of effective treatment.

- Choose treatments for women who are breastfeeding with the lowest known risk and keep in mind that there is very limited knowledge about long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes.

- Where there is no clear evidence base that one drug is safer during breastfeeding than another, the best option may be not to switch.

- There is little clear evidence to support the discarding of breastmilk or timing of breastfeeding in relation to time of maternal drug administration. Such recommendations could potentially add to the difficulties and challenges of establishing breastfeeding

- Monitor the infant for adverse effects such as (but not limited to) over sedation and poor feeding.

- These recommendations in general apply to term, healthy infants. Great caution should be exercised in decisions around maternal psychotropic prescribing for breastfed premature or sick infants, and where the mother is taking more than one drug.

BIRTH TRAUMA AND POST-TRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER

It has been estimated that 33–45% of women will experience birth trauma.11,12 Furthermore, 4% of the postnatal population will develop post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), with rates of PTSD rising to 18% in high-risk groups.11 High-risk groups included women who had experienced a difficult or traumatic birth, had emergency cesarean sections, severe fear of birth, a history of sexual/physical violence or childhood abuse, babies that were born very low birth weight, preterm, or diagnosed with fetal anomaly, or who had severe pregnancy complications such as hyperemesis gravida, pre-eclampsia or HELLP syndrome.13

WHO estimated that over 141 million babies would be born in 2019.14 This means potentially in 2019 there were 46–63 million women with symptoms of birth trauma and 5.6 and 25 million women with PTSD in normal and high-risk groups, respectively.

Symptoms of PTSD:15

- Re-experiencing (flashback, imagery, nightmares re-living the trauma);

- Avoidance (site of trauma or links to trauma, e.g. avoiding maternity hospital or watching TV about childbirth);

- Hyperarousal (including hypervigilance, anger and irritability);

- Negative alterations in mood and thinking;

- Emotional numbing;

- Dissociation (feeling disconnected with yourself or world around you);

- Emotional dysregulation;

- Interpersonal difficulties or problems in relationships;

- Negative self-perception (including feeling diminished, defeated or worthless).

Women with birth trauma can have a number of symptoms of PTSD but do not fulfil the full diagnostic criteria.

Treatment of PTSD will vary with local availability of services worldwide. Primarily, treatment should be psychologically based. Trauma focussed cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and eye-movement desensitization and reprogramming (EMDR) are specialized treatments that WHO recommends as treatment after trauma.16 If available, a referral should be made to local psychological services and potentially adult or perinatal psychiatric service. WHO recommend against the use of benzodiazepines for use in trauma within the first month following a traumatic event.

Women with co-morbid symptoms may be treated with appropriate medication, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for depressive symptoms.

PERINATAL OBSESSIVE COMPULSIVE DISORDER

Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) is a relatively common mental illness (lifetime prevalence of 1–2%). It can affect men and women at any time of life. If a woman has OCD during pregnancy or after birth, it is called perinatal OCD.17

Recent studies suggest that OCD is more common in the perinatal period than at any other time in life. Some people develop OCD for the first time, whilst others find their pre-existing symptoms worsen.18

OCD is a specific anxiety disorder. It is composed of the following characteristics:

- Obsessional thoughts, images or impulses – these are recurrent, intrusive and ego dystonic (in conflict with normal thoughts or ideals, e.g. a thought to harm someone which is the opposite of what you want to do);

- Compulsive actions – these are repetitive, and purposeful behaviors or mental acts which aim to neutralize the obsessional thoughts;

- The above thoughts and actions impact on the ability to function adequately.

Common obsessions and compulsions19

Obsessions

- contamination

- order or symmetry

- safety

- doubt (of memory for events or perceptions)

- unwanted intrusive sexual or aggressive thoughts

- scrupulosity (the need to do the right thing or fear of committing an error, breaking the law or religious transgression).

Compulsions

- checking (e.g. doors, windows, electric sockets, appliances, safety of children)

- cleaning or washing excessively

- counting or repeating actions a specific number of times

- arranging objects in a specific way

- touching or tapping objects

- hoarding

- confessing or constantly seeking reassurance

- continual list making.

Differential diagnosis (see glossary for fuller description of terms)

- “normal” (but recurrent) thoughts, worries or habits (they do not cause distress or functional impairment)

- anankastic personality disorder

- schizophrenia

- phobias

- depressive disorder

- hypochondriasis

- body dysmorphic disorder

- trichotillomania.

Management of perinatal OCD20

Management can be psychological, pharmacological or both. Availability of psychology will differ across the world and would be first-line treatment for mild to moderate symptoms.

Psychological management

Cognitive behavioral therapy – recommended by NICE essentially the advice is to take a behavioral approach, including exposure and response prevention. Some online advice can be found at www.getselfhelp.co.uk.

Pharmacological management21

Antidepressants – selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), e.g. escitalopram, fluoxetine, sertraline, paroxetine and fluvoxamine – should be considered as first-line treatment. There is no clear superiority of any one agent over another. High doses are usually needed and it can take at least 12 weeks for treatment response.

Second-line treatment is clomipramine as it has specific anti-obsessional action.

Augmentative strategies for difficult to treat cases, these include the use of antipsychotics (e.g. risperidone, haloperidol, pimozide) especially if psychotic features, tics or schizotypal traits.

ATTACHMENT AND BONDING

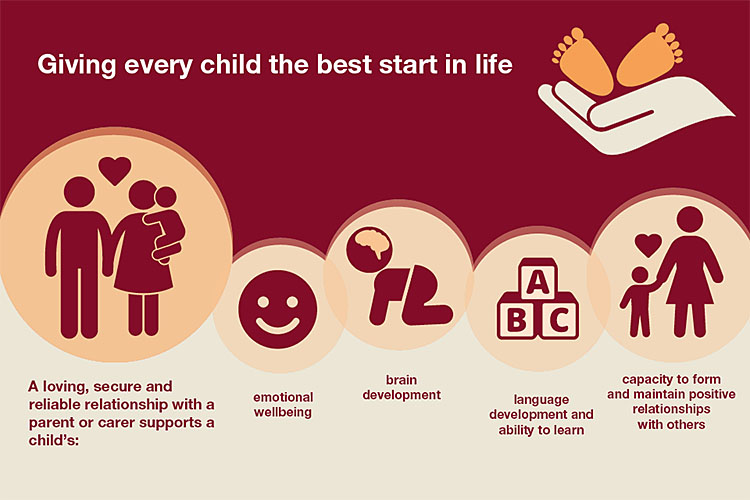

Attachment refers to the specific aspect of the relationship between an infant and their care giver that helps them feel safe and secure.22 Early attachment lays the foundation for the child’s personality, impacts their emotional, social and cognitive development and forms the foundation of their ability to connect with others in a healthy way.23 Secure attachments develop when baby’s needs are responded to in warm, sensitive and consistent ways. Children with secure attachments tend to have better outcomes.24

1

An illustration of how secure attachments support children’s development.25

Bonding can be described as the “emotions and cognitions towards one’s infant”.26 Bonding often starts in early infancy, but is an ongoing process. It takes different amounts of time for different people and mothers bond with babies in different ways. Sometimes perinatal mental health difficulties can make developing this relationship more difficult.27 For instance a woman experiencing postnatal depression may have negative thoughts about her baby; this may impact the bonding process.

Signs a mother may have difficulty bonding include:

- feeling they do not know their baby

- feeling their baby does not seem to know them

- having mixed feelings towards their baby

- feeling like their baby has negative feelings towards them

- feeling they don’t have the energy to interact and connect with baby

- feeling like no matter how much time they spend with baby they never seem to respond in the right way.

It is normal for a new mother to feel some of these for a short period of time; however, when these feelings persist, encouraging a mother to do the following may be beneficial:

- spending time together and simply getting to know one another

- holding and cuddling baby, keeping them close and practicing skin to skin contact

- copying baby’s noises, waiting for a response before continuing

- singing and telling rhymes to baby

- reading to baby

- making eye contact with and talking to baby using a soothing tone

- trying baby massage – this has been found to support the mother-infant relationship28

- playing some simple games together, e.g. peek-a-boo based games

- making faces at baby and seeing if they copy these/copying their facial expressions

- engaging in activities they enjoy with baby

- identifying what they like about their baby.

Completing a referral where available to perinatal psychology may also be beneficial.

PUERPERAL PSYCHOSIS

This is a medical emergency and needs immediate assessment and treatment please refer to this link.

POSTNATAL DEPRESSION

Postnatal depression (PND) is a common illness affecting approximately 15% of women. It can vary in onset and severity of symptoms. There may be no reason for symptoms but the following may increase risk:

- previous mental health problems

- antenatal depression or anxiety

- poor social support

- other recent stressors

- domestic violence or abuse.

A full GLOWM chapter discusses postnatal depression in detail here.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- Mental health problems in the perinatal period are common, but they are treatable with identification, support, medication and psychology or psychotherapy.

- It is important to take a detailed history and examination to aid diagnosis and treatment.

- Red flags for completed suicide include new violent thoughts of self-harm or suicide, rapidly changing mental state, and estrangement or disengagement from baby.

- Puerperal psychosis is a medical emergency and requires immediate assessment and management.

- Birth trauma symptoms are common (in 35–45% of pregnancies) and up to 5% may meet criteria for PTSD. Psychological treatment should be offered if available.

- Breastfeeding can still be promoted with the majority of medications and databases are available freely to review evidence base.

- Identifying and improving attachment and bonding difficulties with help both mother and infant mental health.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) of this chapter declare that they have no interests that conflict with the contents of the chapter.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

GLOSSARY OF SOME TERMS IN THE CHAPTER

Anankastic personality disorder – is characterized by preoccupation with orderliness, perfectionism, and mental and interpersonal control, at the expense of flexibility, openness, and efficiency. This pattern begins by early adulthood and is present in a variety of contexts. Historically, this has been conceptualized as bearing a close relationship with obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Anhedonia – absence of enjoyment. A core symptom of depression.

Body dysmorphic disorder – a person may have severe anxiety about flaws in their appearance, which are often unnoticed by others.

Delusion – an abnormal belief, held with complete conviction in absence of evidence and not in keeping with cultural norms. Can manifest in different ways such as paranoid, grandiose, guilty, love, controlled by external agency.

Hallucination – a perception without the requisite stimulus. Can be visual, auditory, tactile or olfactory. Example of auditory hallucination can be hearing voices either be second person (voice talks to patient) or third person (voices talking to each other).

Hypochondriasis – a health anxiety that the person is suffering form a serious medical condition, often after negative test. Can be difficult to assess and manage psychologically.

Stigma – when someone is unfairly criticized or treated differently based on certain characteristic such as mental illness or physical disability.

Trichotillomania – irresistible urge to pull hair from their body including scalp, eyelashes, eyebrows, genital area.

REFERENCES

Bauer A, Parsonage M, Knapp M, et al. The costs of perinatal mental health problems [internet]. London: Centre for Mental Health, 2014 [cited 23 Aug 2020]. Available from: https://www.nwcscnsenate.nhs.uk/files/3914/7030/1256/Costs_of_perinatal_mh.pdf | |

Fisher J, Cabral de Mello M, Patel V, et al. Prevalence and determinants of common perinatal mental disorders in women in low- and lower-middle-income countries: a systematic review. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2011;90(2):139–49. | |

Maternal Mental Health: Why it matters and what countries with limited resources can do. Knowledge Summary 31. The Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health, 2014. https://www.who.int/pmnch/knowledge/publications/summaries/en/ | |

World Health Organization. 10 Facts on mental health- Stigma and discrimination against patients and families prevent people from seeking mental health care [internet]. Geneva: World Health Organisation, no date [cited 23rd Aug 2020]. Available from: https://www.who.int/features/factfiles/mental_health/mental_health_facts/en/index5.html | |

Mother and Babies: Reducing Risk through Audits and Confidential Enquiries across the UK. Saving Lives, Improving Mothers’ Care Surveillance of maternal deaths in the UK 2011–13 and lessons learned to inform maternity care from the UK and Ireland Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity 2009–13 [internet]. Oxford: MBRRACE UK, 2015 [cited 23rd Aug 2020]. Available from: https://www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/downloads/files/mbrrace-uk/reports/MBRRACE-UK%20Maternal%20Report%202015.pdf | |

Zero Suicide Alliance. Take the training [internet]. Zero Suicide Alliance, 2020 [cited 4th Aug 2020]. Available from: https://www.zerosuicidealliance.com/training | |

World Health Organization. Global strategy for infant and young child feeding [internet]. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2003 [cited 28th Aug 2020]. Available from: https://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/9241562218/en/ | |

Hale T. Medications & Mother’s Milk [internet]. New York: Springer Publishing Company, 2014 [cited 12 Jul 2020]. Available from: http://www.medsmilk.com | |

Lactmed. Drugs and Lactation Database [internet]. Bethesda MD: National Library of Medicine (US), 2006 [cited 4th Sep 2020]. Available from: https://www.toxnet.nlm.nih.gov/newtoxnet/lactmed.htm | |

McAllister-Williams R, Baldwin D, Cantwell R, et al. British Association for Psychopharmacology consensus guidance on the use of psychotropic medication preconception, in pregnancy and postpartum 2017. Journal of Psychopharmacology 2017;31(5):519–52. | |

Bailham D, Joseph S. Post-traumatic stress following childbirth: A review of the emerging literature and directions for research and practice. Psychology, Health & Medicine 2003;8(2):159–68. | |

Patterson J, Hollins Martin C, Karatzias T. PTSD post-childbirth: a systematic review of women’s and midwives’ subjective experiences of care provider interaction, Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology 2019;37:1:56–83 | |

Yildiz P, Ayers S, Phillips L. The prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in pregnancy and after birth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders 2017;208:634–45. | |

World Health Organization. Health Statistics Overview 2019: monitoring health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals [internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2019 [cited 28th Aug 2020]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/311696/WHO-DAD-2019.1-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y | |

National Institute of Health Care and Excellence. Post-traumatic stress disorder (NICE guideline [NG116]) [internet]. London: NICE, 2018 [cited 21st Aug 2020]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng116 | |

World Health Organisation. Guidance on mental health care after trauma [internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2013 [cited 23rd Aug 2020]. Available from: https://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2013/trauma_mental_health_20130806/en/ | |

Royal College of Psychiatrists. Perinatal OCD [internet]. London: Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2018 [cited 23rd Aug 2020]. Available from: https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/mental-health/problems-disorders/perinatal-ocd | |

Maternal OCD. About perinatal OCD [internet]. Maternal OCD, no date [cited 21st Aug 2020]. Available from: www.maternalocd.org | |

Semple D, Smyth R. Oxford Handbook of Psychiatry. 4th edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019. | |

National Institute for Health Care and Excellence. Obsessive- compulsive disorder and body dysmorphic disorder treatment (Clinical guideline [CG31]) [internet]. London: NICE, 2005 [cited 28rd Aug 2020]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG31/chapter/1-Guidance | |

Baldwin D, Anderson I, Nutt D, et al. Evidence-based pharmacological treatment of anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder: A revision of the 2005 guidelines from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. Journal of Psychopharmacology 2014;28(5):403–39. | |

Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss. Volume 1: Attachment. 2nd edn. New York, USA: Basic Books; 1982. | |

Benoit, D. Infant-parent attachment: Definition, types, antecedents, measurement and outcome. Paediatrics & Child Health 2004;9(8):541–5 | |

Ranson K, Urichuk L. The effect of parent–child attachment relationships on child biopsychosocial outcomes: a review. Early Child Development and Care 2008;178(2):129–52. | |

GOV UK. Health matters: giving every child the best start in life [internet]. London: GOV UK; 2016 [cited 23rd Aug 2020]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-matters-giving-every-child-the-best-start-in-life/health-matters-giving-every-child-the-best-start-in-life | |

Hairston I, Handelzalts J, Lehman-Inbar T, et al. Mother-infant bonding is not associated with feeding type: a community study sample. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2019;19(1):1–12. | |

Winston R, Chicot, R. The importance of early bonding on the long-term mental health and resilience of children. London Journal of Primary Care 2016; 8(1):2–14. | |

Gürol A, Polat S. The Effects of Baby Massage on Attachment between Mother and their Infants. Asian Nursing Research 2012;6(1):35–41. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards programme CLICK HERE)